Abstract

Purpose

Radiotherapy to the prostate gland and pelvic lymph nodes may cause acute and late bowel symptoms and diminish quality of life. The aim was to study the effects of a nutrition intervention on bowel symptoms and health-related quality of life, compared with standard care.

Methods

Patients were randomised to a nutrition intervention (n = 92) aiming to replace insoluble fibres with soluble and reduce intake of lactose, or a standard care group (n = 88) who were recommended to maintain their habitual diet. Bowel symptoms, health-related quality of life and intake of fibre and lactose-containing foods were assessed up to 24 months after radiotherapy completion. Multiple linear regression was used to analyse the effects of the nutrition intervention on bowel symptoms during the acute (up to 2 months post radiotherapy) and the late (7 to 24 months post radiotherapy) phase.

Results

Most symptoms and functioning worsened during the acute phase, and improved during the late phase in both the intervention and standard care groups. The nutrition intervention was associated with less blood in stools (p = 0.047), flatulence (p = 0.014) and increased loss of appetite (p = 0.018) during the acute phase, and more bloated abdomen in the late phase (p = 0.029). However, these associations were clinically trivial or small.

Conclusions

The effect of the nutrition intervention related to dietary fibre and lactose on bowel symptoms from pelvic RT was small and inconclusive, although some minor and transient improvements were observed. The results do not support routine nutrition intervention of this type to reduce adverse effects from pelvic radiotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Radiotherapy (RT) is a well-established treatment option for patients with intermediate or high-risk prostate cancer. Despite technical advances in delivery, pelvic RT exposes parts of the bowel to some degree of radiation, and 90% of patients experience a change in bowel habits during treatment [1,2,3]. Acute symptoms such as diarrhoea, abdominal pain and urgency can occur during the treatment period and may subside after RT completion [1, 4]. In addition, severe acute symptoms increase the risk of late bowel symptoms [5]. Late side effects, i.e. symptoms that persist or develop months to years after RT, can be permanent and progressive in severity and may include diarrhoea, urgency, rectal bleeding and incontinence [6]. Approximately 50% of patients report that their quality of life is affected by late bowel symptoms, and 20–40% report that this effect is moderate or severe [7, 8].

Nutrition interventions (NI) in cancer care can comprise approaches such as dietary counselling and dietary modification [9, 10]. Previous studies have evaluated NI such as elemental diet, fibre supplementation, lactose restriction and modification of fat and fibre intake, in order to reduce bowel symptoms from pelvic RT [2, 9, 11,12,13]. Dietary fibres can be differentiated into insoluble fibres which increases stool bulk and have a laxative effect, and soluble fibres which are fermented to a higher degree and enhances short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production [14], which could potentially reduce inflammatory processes [15, 16]. Lactose intolerance may occur from pelvic RT due to a reduction in brush-border enzyme and can contribute to bowel symptoms [17]. A variety of advices on a modified fibre or lactose intake are provided in the clinic to patients undergoing pelvic RT, which reflects the lack of consensus in this area [18]. Previous NI have shown some benefits in reducing bowel symptoms from pelvic RT, but there is still not enough evidence, and there is a need for high-quality studies with long-term follow-up [2, 9, 12, 13].

We have previously conducted a randomised controlled trial (RCT), with an NI aiming for a reduced intake of insoluble fibre and lactose, among men with localised prostate cancer undergoing curative RT restricted to the prostate gland. Descriptive data revealed a tendency towards less acute bowel symptoms in the intervention group. This trend did not persist in the long-term evaluation [11, 12]. However, larger irradiated volumes, including the prostate gland and pelvic lymph nodes, may increase bowel symptoms and thereby the benefit from the NI [19].

Aim

The aim of the paper is to study the effects of an NI, aiming to replace foods high in insoluble fibre and lactose with foods with a higher proportion of soluble fibre and low in lactose, on acute and late bowel symptoms and health-related quality of life (HRQoL), among men undergoing RT to the prostate gland and pelvic lymph nodes, compared with standard care.

Material and methods

Design

This study is a RCT evaluating the same NI on the same outcome measures as in our previous RCT [11, 12], i.e. bowel symptoms as the primary outcome measure and HRQoL as the secondary outcome measure.

Patients

From October 2009 to January 2014, consecutive patients with intermediate- or high-risk localised prostate cancer referred to curative RT, at Uppsala, Karlstad or Gävle hospital in Sweden, were assessed for eligibility. Exclusion criteria were cognitive impairment, previous RT to the pelvis, inflammatory bowel disease, need for long-term hospital care or inability to speak or understand Swedish. Eligible patients received written and oral information about the study during a visit to the hospital or by telephone. One hundred and eighty (72%) of 249 approached patients gave their informed consent to participate (Fig. 1). The Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala approved the study (Dnr 2009/209).

Flow chart. Note: ‘Did not complete questionnaires’: the number of patients who did not complete the specific assessment point but did not withdraw from the study. First appointment with the dietitian: the start of radiotherapy, 4 and 8 weeks: after the start of radiotherapy, 2, 7, 12, 18 and 24 months: after radiotherapy completion

Radiotherapy

Patients treated in Uppsala received irradiation of the prostate, seminal vesicles and pelvic lymph nodes with intensity-modulated radiation technique (IMRT) or volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) (Table 1). A prostate boost was given with brachytherapy, with a fortnight’s pause halfway through the IMRT/VMAT treatment, or by protons, or photons using 3D-conformal EBRT, with a 1-week pause before the IMRT/VMAT treatment. Patients in Karlstad received irradiation of the prostate, seminal vesicles and pelvic lymph nodes with IMRT, and a boost to the prostate. Patients in Gävle received irradiation of the prostate, seminal vesicles and pelvic lymph nodes with rapid arc technique, and a boost to the prostate.

Power analysis and randomisation

A 5-point change in the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality-of-life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) scales is considered clinically significant [20]. Given a mean difference of five in bowel symptoms between groups, and using a standard deviation of 9.4 from previous research [21], the effect size was calculated to 0.53. To reach a power of 80%, with our estimated effect size and a 0.05 significance level, 57 patients in each group were required. Expecting an attrition rate of approximately 30% due to the extensive follow-up period, we decided to include 90 patients in each group. Patients were stratified by radiation technique and site, and randomly assigned to a nutrition intervention group (NIG, n = 92) or a standard care group (SCG, n = 88). Randomisation was performed by two persons unrelated to the trial, using the Efron’s biased coin design [22].

The nutrition intervention

The NI comprised three individual sessions (approximately 30–60 min) with a research dietitian, face-to-face at baseline (onset of RT) and 4 weeks after baseline (mid treatment), and by telephone at 8 weeks (end of treatment). Spouses were welcome to participate. The NIG was advised to replace foods high in insoluble fibre and lactose with foods with a high proportion of soluble fibre and low in lactose, during the entire study period (26 months). The dietary advice was standardised and food items were categorised as ‘recommended’ and ‘not recommended’ (Supplementary File A). Advice regarding boiling of vegetables and mixing of soups to aid digestion was also provided. A dietary advice pamphlet was handed out at baseline and sent by mail as a reminder at all assessment points except for the last at 26 months. The NIG completed food records at two occasions, according to the same purpose and methods described previously [11].

Standard care

The SCG was recommended to continue their habitual diet. Routine dietary counselling was not part of the standard care for this patient category, but dietitian consultation was offered if needed. Two patients in the SCG received dietary counselling regarding bowel symptoms and one about nutritional drinks.

Data collection

Bowel symptoms, HRQoL and dietary adherence were assessed at eight assessment points (Fig. 1). All patients completed baseline data collection before being informed about the randomisation.

Clinical and demographic characteristics

Demographics and medical data were collected from medical records or obtained at the baseline visit. Information regarding proctitis, eventual lower intestinal endoscopies, urinary tract infection, use of antibiotics and hospitalisation during and after RT were collected from medical records at 1 and 24 months after RT completion. Information regarding cancer recurrence and additional oncological treatment were collected at 24 months. Nutritional status was assessed with the Scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) tool at baseline and the PG-SGA Short Form at 12 and 24 months after RT [23, 24].

Bowel symptoms and HRQoL

Diarrhoea and constipation were assessed with the EORTC QLQ-C30 [25]. Limitations to daily activities due to bowel symptoms, unintentional leakage of stools, blood in stools and bloated abdomen were assessed with the prostate-specific module QLQ-PR25 [21]. Patient-perceived bother from eight bowel symptoms was assessed with the Gastrointestinal Side Effects Questionnaire (GISEQ). Two additional questions asked for other bowel symptoms (yes/no) and use of medication due to bowel symptoms (Yes/No) [11, 12, 26]. Additional aspects of HRQoL, including global health status, functioning and symptoms, were assessed with EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PR25.

Dietary adherence

A food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) concerning the intake of 61 fibre- and lactose-containing food items during the previous month (never/less than once a month up to ≥ 3 times/day) was completed at all assessments. Two additional questions concerned use of lactose-reduced dairy products (yes/no) and type of products. No portion sizes were measured.

FFQ data were calculated into adherence scores, an approach used in previous studies [27,28,29]. Food items with a median of ≥ 2 times/month (n = 30) were categorised into not recommended and recommended grain products, not recommended and recommended vegetables and high-lactose and low-lactose dairy products. The median intake per day for each of the six food categories was calculated for all assessment points (Supplementary File, B). The food categories were dichotomised using the group median and assigned a value of 0 (not recommended) or 1 (recommended foods). Use of lactose-free/reduced dairy products was scored 1 (yes) or 0 (no). In this way, each patient was assigned an adherence score at each assessment point ranging from 0 (low adherence) to 7 (high adherence).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 and R version 3.4.3 (multivariate linear regression, MLR, analyses). The QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PR25 were scored in accordance with the EORTC scoring manual [30]. Bowel symptoms in the QLQ-PR25 were analysed both as single items and as the bowel symptoms scale [21]. MLR was used to analyse how the NI was associated with bowel symptoms and HRQoL during the acute phase (the overall mean value of the assessment at 4 weeks and 8 weeks after RT start, and 2 months post-RT) and the late phase (the overall mean value of the assessment at 7, 12, 18 and 24 months post-RT). All models were adjusted for the baseline value, age at randomisation, radiotherapy dose, diabetes and smoking. Models analysing the late phase were also adjusted for acute phase value.

Analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) and per protocol [31]. Missing data during the acute or late phase in the ITT analysis were substituted with the mean of the patient’s responses [32], provided that baseline and at least one assessment during the acute or late phase had been completed. Patients in the NIG who were considered adherent (n = 27), i.e. an adherence score ≥ 3 at all assessment points during the acute phase, were included in the per-protocol analyses and compared with the patients in the SCG who did not have a reduced intake of insoluble fibre and lactose (i.e. an adherence score < 3 during the acute phase, (n = 47)) [31]. The number and proportion of patients reporting bowel symptoms to be at least ‘a little’ and ‘quite a bit’ bothersome, at one or more assessments, were calculated for QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PR25 single-item symptoms. The Student’s unpaired t test and the chi-square test were used to analyse differences between groups at baseline. Charlson’s Comorbidity Index was used to calculate the comorbidity burden [33].

Results

No statistically significant differences between the NIG and the SCG were found regarding baseline characteristics (Table 2), bowel symptoms at baseline, proctitis, urinary tract infection, use of antibiotics, hospitalisation, additional oncological treatment or cancer recurrence, at 1 and 24 months after RT completion. Eight of the 151 patients who completed their participation in the trial had cancer recurrence documented in the medical journals at 24 months after RT. Six patients in the NIG and two in the SCG received adjuvant chemotherapy (docetaxel) after RT completion, and one patient in the NIG and one in the SCG underwent chemotherapy (docetaxel) due to cancer recurrence.

Dietary adherence

The most obvious changes were observed during the acute phase. The patients in the NIG reduced their intake of non-recommended grains, bread, vegetables and fruits and increased their intake of recommended grains, bread, vegetables and fruits (Supplementary File, B). Adherence subsided during the late phase. The intake of dairy products was stable throughout the study period; the use of or lactose-reduced products was most frequent during the acute phase.

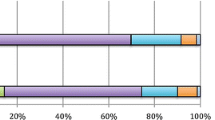

NI associations with bowel symptoms

The baseline levels of bowel symptoms were low in both groups. Most bowel symptoms worsened from baseline during the acute phase and then improved during the late phase, although not returning completely to baseline levels (Fig. 2, Table 3). The NI was associated with less bother from blood in stools (p = 0.047) and less bother from flatulence (p = 0.014) during the acute phase but these differences were not clinically significant. However, the NI was associated with an increase in bloated abdomen during the late phase (p = 0.029) (Table 3). There were no associations between the NI and bowel symptoms in the per-protocol analyses (data not shown).

Mean scores for bowel symptoms at baseline, 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 2 months, 7 months, 12 months, 18 months and 24 months. Variables from the QLQ-C30, QLQ-PR25 and GISEQ assessing bowel symptoms among patients with prostate cancer undergoing radiotherapy, who received the nutrition intervention (NIG) and those who received standard care (SCG). Abbreviations: Bloating, bloated abdomen; Bowel symptoms, aggregated scale bowel symptoms; Limitations, limitations of daily activities due to bowel symptoms; Leakage, unintentional leakage of stools. Note: Scores ranges from 0 to 100 in EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PR25, and from 0 to 10 in GISEQ

Covariate associations with bowel symptoms

Higher levels of bowel symptoms at baseline were associated with higher levels of symptoms during the acute phase (p < 0.004), except for constipation, blood in stools, abdominal cramps and limitations to daily activities due to bowel symptoms. Higher levels of constipation, abdominal cramps, unintentional leakage of stools, bloated abdomen and bowel symptoms at baseline were associated with more symptoms during the late phase (p < 0.001). More bowel symptoms during the acute phase were associated with more symptoms during the late phase (p < 0.0001–0.043), except for blood in stools. Higher radiation dose was associated with more constipation during the acute phase (p = 0.030). Former smoking was associated with a less bloated abdomen during the acute phase (p = 0.037), using never smokers as a reference.

Prevalence of bowel symptoms

Diarrhoea was the most prevalent symptom during the acute phase, 76% in the NIG and 69% in the SCG reported at least ‘quite a bit’ of diarrhoea (Table 4). Other symptoms rated ‘quite a bit’ during the acute phase were limitations to daily activities due to bowel symptoms and bloated abdomen. Bloated abdomen was also the most common symptom during the late phase. Blood in stools was less prevalent in the NIG compared with the SCG during the acute and the late phase. There were no differences between the groups regarding the self-reported data on other bowel symptoms, or use of medication due to bowel symptoms during or after RT (data not shown).

NI associations with HRQoL

Global health status, functioning and symptoms worsened during the acute phase and improved during the late phase, although not returning to baseline levels for all variables, and without obvious differences between the groups (Supplementary File, C). Dyspnoea worsened during the late phase. Urinary symptoms were the worst symptoms during the acute phase, and fatigue, insomnia and hormonal treatment–related symptoms during the late phase. The NI was associated with more loss of appetite during the acute phase (p = 0.018). No other associations were found between the NI and HRQoL domains.

Covariate associations with HRQoL

Higher functioning and more symptoms at baseline were associated with higher functioning and more symptoms during the acute and late phases (p < 0.0001–0.027). Exceptions were sexual functioning during the acute phase, and global health status, cognitive functioning, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea and sexual functioning during the late phase. A higher acute phase value was associated with higher functioning and more symptoms during the late phase (p < 0.001), except for appetite loss and sexual functioning. There were some scattered associations between radiation dose, age, diabetes, smoking and HRQoL domains, but no obvious pattern or strong associations were found (data not shown).

Discussion

The observed associations between the NI and bowel symptoms were small and inconclusive. The NIG reported statistically, but not clinically significant, less bother from blood in stools and flatulence in the acute phase, but more bloated abdomen during the late phase. Also, the NI seemed to affect the patients’ appetites negatively during the acute phase. Thus, the results do not provide support for an NI aiming to replace foods high in insoluble fibre and lactose with foods with a higher proportion of soluble fibre and low in lactose, during RT against prostate cancer. Quite a large proportion of the NIG were not considered adherent, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding the effects of the NI. The lack of strong effects from the NI is supported by the per-protocol analyses, since no differences were found between adherers and patients who did not have a reduced intake of insoluble fibre and lactose.

Furthermore, it must be taken into consideration that the distinction between soluble and insoluble dietary fibres is complex [34]. A recent RCT found that a high-fibre diet–reduced gastrointestinal toxicity compared with habitual fibre intake, both in the acute and late phases [35]. A higher fibre intake will also increase the intake of soluble fibres which may be beneficial due to the enhanced production of SCFA, which could potentially reduce inflammatory processes [16]. Further investigations of the effects of a high-fibre diet during pelvic RT are recommended.

Blood in stools and flatulence may be induced by pelvic RT [8], and the associations between the NI and these symptoms may indicate some small effects of the NI. However, the difference between the groups was minor, and of small or no clinical significance. The NI was associated to more loss of appetite during the acute phase; this may be explained by the reason that the NIG had to change their diet during pelvic RT which may also cause appetite loss [36]. The NIG experienced more bloated abdomen during the late phase compared with the SCG; the five-point difference was small but may be considered clinically significant [20]. This difference may be due to an increasing intake of fibre and lactose over time. Production of gas is a known side effect of fibre ingestion and unabsorbed lactose and can cause discomfort and bloating [37, 38].

The pattern of worsening bowel symptoms during the acute phase fits well with previous research [1, 6]. More than one of four patients were bothered ‘quite a bit’ of diarrhoea, bloated abdomen and/or limitations to daily activities due to bowel symptoms during the late phase. This corroborate earlier findings [7, 8] and highlights the need for interventions to decrease late bowel symptoms from extended field RT for prostate cancer. Our previous RCT revealed a similar pattern of acute and late bowel symptoms [11, 12]; however, a larger proportion of patients in the present study reported ‘quite a bit’ of late bowel symptoms, indicating that a larger irradiated volume, as expected, increased bowel symptoms and decreased HRQoL. Ten patients started chemotherapy during the late phase. Side effects from chemotherapy may have contributed to some of the late symptoms, and this should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results.

The importance of screening for pre-existing bowel symptoms in order to adequately evaluate radiotherapy-induced bowel symptoms has been highlighted [39]. We observed that higher levels of bowel symptoms at baseline were associated with more symptoms during both the acute and the late phases for the majority of symptoms. Furthermore, more bowel symptoms during the acute phase were associated with more bowel symptoms during the late phase except for blood in stools. All patients in the NIG received the same dietary advice, whether they had pre-existing symptoms or not. It is possible that screening for pre-existing bowel symptoms before RT, and targeting tailored NI to patients with symptoms, could be beneficial.

HRQoL is generally high among patients with prostate cancer treated with RT and comparable with normative data, but symptoms such as bowel and urinary problems and sleep disturbances are more pronounced [40, 41]. In our study, there were clinically significant impairments in functioning and symptoms [20] during the acute phase which did not recover completely during the follow-up period, again, pointing to the need for supportive interventions for patients with prostate cancer undergoing RT.

Methodological discussion

A strength of this study is its experimental design with long-term follow-up until 2 years after RT completion. However, NI studies requiring long-term adherence are not without difficulties. Twenty-two (24%) patients in the NIG, and three in the SCG, withdrew from the study, the majority of them during the acute phase. Since withdrawal was not balanced between groups, it is probably not random and is thus difficult to adjust for and might decrease the internal validity of the study. Dietary counselling was conducted at three times during the acute phase. Adherence could possibly have been improved if there had been more dietitian appointments, during both the acute and the late phases, as suggested by the patients in a qualitative interview study [42]. Furthermore, many patients had to travel quite a distance to their treatments, which might have affected their perseverance in planning and preparing food according to the dietary advice.

Another limitation is that the reduction of insoluble fibre and lactose might have been too small to be effective. No target levels for the insoluble fibre and lactose reduction were defined, and it is possible that defined goals for reduction in insoluble fibre and lactose, and an index for self-assessment of adherence, would have been helpful. On the other hand, this would impose a greater workload on the patients. Finally, another limitation is that an extended follow-up period (> 5 years) is required to fully appreciate late bowel symptoms, since such symptoms may worsen beyond 2 years [43].

To conclude, the effect of a modified intake of dietary fibre and lactose on bowel symptoms from pelvic RT was small and inconclusive, although some minor and transient improvements were observed. The results do not support routine NI of this type to reduce adverse effects from pelvic RT. There is a need for more NI studies to reduce pelvic radiotherapy-induced bowel symptoms.

References

Khalid U, McGough C, Hackett C, Blake P, Harrington KJ, Khoo VS, Tait D, Norman AR, Andreyev HJ (2006) A modified inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire and the Vaizey Incontinence questionnaire are more sensitive measures of acute gastrointestinal toxicity during pelvic radiotherapy than RTOG grading. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 64(5):1432–1441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.10.007

Lawrie TA, Green JT, Beresford M, Wedlake L, Burden S, Davidson SE, Lal S, Henson CC, Andreyev HJN (2018) Interventions to reduce acute and late adverse gastrointestinal effects of pelvic radiotherapy for primary pelvic cancers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:Cd012529. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012529.pub2

Budaus L, Bolla M, Bossi A, Cozzarini C, Crook J, Widmark A, Wiegel T (2012) Functional outcomes and complications following radiation therapy for prostate cancer: a critical analysis of the literature. Eur Urol 61(1):112–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2011.09.027

Dearnaley DP, Khoo VS, Norman AR, Meyer L, Nahum A, Tait D, Yarnold J, Horwich A (1999) Comparison of radiation side-effects of conformal and conventional radiotherapy in prostate cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet (London, England) 353(9149):267–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(98)05180-0

Peach MS, Showalter TN, Ohri N (2015) Systematic review of the relationship between acute and late gastrointestinal toxicity after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer 2015:624736. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/624736

Ahmad SS, Duke S, Jena R, Williams MV, Burnet NG (2012) Advances in radiotherapy. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 345:e7765. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e7765

Andreyev HJ (2007) Gastrointestinal problems after pelvic radiotherapy: the past, the present and the future. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 19(10):790–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2007.08.011

Gami B, Harrington K, Blake P, Dearnaley D, Tait D, Davies J, Norman AR, Andreyev HJ (2003) How patients manage gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 18(10):987–994

Henson CC, Burden S, Davidson SE, Lal S (2013) Nutritional interventions for reducing gastrointestinal toxicity in adults undergoing radical pelvic radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11:CD009896. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009896.pub2

Paccagnella A, Morassutti I, Rosti G (2011) Nutritional intervention for improving treatment tolerance in cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol 23(4):322–330. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283479c66

Pettersson A, Johansson B, Persson C, Berglund A, Turesson I (2012) Effects of a dietary intervention on acute gastrointestinal side effects and other aspects of health-related quality of life: a randomized controlled trial in prostate cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 103(3):333–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2012.04.006

Pettersson A, Nygren P, Persson C, Berglund A, Turesson I, Johansson B (2014) Effects of a dietary intervention on gastrointestinal symptoms after prostate cancer radiotherapy: long-term results from a randomized controlled trial. Radiother Oncol 113(2):240–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2014.11.025

Wedlake LJ, Shaw C, Whelan K, Andreyev HJ (2013) Systematic review: the efficacy of nutritional interventions to counteract acute gastrointestinal toxicity during therapeutic pelvic radiotherapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 37(11):1046–1056. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12316

Vanhauwaert E, Matthys C, Verdonck L, De Preter V (2015) Low-residue and low-fiber diets in gastrointestinal disease management. Adv Nutr (Bethesda, Md) 6(6):820–827. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.115.009688

Cook SI, Sellin JH (1998) Review article: short chain fatty acids in health and disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 12(6):499–507

Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, Curi R (2011) Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients 3(10):858–876. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu3100858

Andreyev J (2007) Gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy: a new understanding to improve management of symptomatic patients. Lancet Oncol 8(11):1007–1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(07)70341-8

Ahlin R, Sjoberg F, Bull C, Steineck G, Hedelin M (2018) Differing dietary advice are given to gynaecological and prostate cancer patients receiving radiotherapy in Sweden. Lakartidningen 115

Lee CT, Dong L, Ahamad AW, Choi H, Cheung R, Lee AK, Horne DF Jr, Breaux AJ, Kuban DA (2005) Comparison of treatment volumes and techniques in prostate cancer radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol 28(6):618–625

Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J (1998) Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16(1):139–144. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1998.16.1.139

van Andel G, Bottomley A, Fossa SD, Efficace F, Coens C, Guerif S, Kynaston H, Gontero P, Thalmann G, Akdas A, D’Haese S, Aaronson NK (2008) An international field study of the EORTC QLQ-PR25: a questionnaire for assessing the health-related quality of life of patients with prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, Engl) 44(16):2418–2424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.030

Efron B (1971) Forcing a sequential experiment to be balanced. Biometrika 58(3):403–417. https://doi.org/10.2307/2334377

Persson C, Sjoden PO, Glimelius B (1999) The Swedish version of the patient-generated subjective global assessment of nutritional status: gastrointestinal vs urological cancers. Clin Nutr 18(2):71–77. https://doi.org/10.1054/clnu.1998.0247

Ottery FD (1994) Rethinking nutritional support of the cancer patient: the new field of nutritional oncology. Semin Oncol 21(6):770–778

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376

Pettersson A, Turesson I, Persson C, Johansson B (2014) Assessing patients’ perceived bother from the gastrointestinal side effects of radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: initial questionnaire development and validation. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 53(3):368–377. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186x.2013.819994

Bach A, Serra-Majem L, Carrasco JL, Roman B, Ngo J, Bertomeu I, Obrador B (2006) The use of indexes evaluating the adherence to the Mediterranean diet in epidemiological studies: a review. Public Health Nutr 9(1a):132–146

Roswall N, Eriksson U, Sandin S, Lof M, Olsen A, Skeie G, Adami HO, Weiderpass E (2015) Adherence to the healthy Nordic food index, dietary composition, and lifestyle among Swedish women. Food Nutr Res 59:26336. https://doi.org/10.3402/fnr.v59.26336

Overby NC, Hillesund ER, Sagedal LR, Vistad I, Bere E (2015) The Fit for Delivery study: rationale for the recommendations and test-retest reliability of a dietary score measuring adherence to 10 specific recommendations for prevention of excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Matern Child Nutr 11(1):20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12026

Fayers PM AN, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A, On behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group (2001) The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer

Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S (2012) Beyond the intention-to-treat in comparative effectiveness research. Clin Trials 9(1):48–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774511420743

Fox-Wasylyshyn SM, El-Masri MM (2005) Handling missing data in self-report measures. Res Nurs Health 28(6):488–495. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20100

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383

Cummings JH, Stephen AM (2007) Carbohydrate terminology and classification. Eur J Clin Nutr 61(Suppl 1):S5–S18. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602936

Wedlake L, Shaw C, McNair H, Lalji A, Mohammed K, Klopper T, Allan L, Tait D, Hawkins M, Somaiah N, Lalondrelle S, Taylor A, VanAs N, Stewart A, Essapen S, Gage H, Whelan K, Andreyev HJN (2017) Randomized controlled trial of dietary fiber for the prevention of radiation-induced gastrointestinal toxicity during pelvic radiotherapy. Am J Clin Nutr 106(3):849–857. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.150565

Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, Barthelemy N, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, Fearon K, Hutterer E, Isenring E, Kaasa S, Krznaric Z, Laird B, Larsson M, Laviano A, Muhlebach S, Muscaritoli M, Oldervoll L, Ravasco P, Solheim T, Strasser F, de van der Schueren M, Preiser JC (2017) ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr 36(1):11–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.07.015

Eswaran S, Muir J, Chey WD (2013) Fiber and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 108(5):718–727. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.63

Deng Y, Misselwitz B, Dai N, Fox M (2015) Lactose intolerance in adults: biological mechanism and dietary management. Nutrients 7(9):8020–8035. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7095380

Bonet M, Cayetano L, Nunez M, Jovell-Fernandez E, Aguilar A, Ribas Y (2018) Assessment of acute bowel function after radiotherapy for prostate cancer: is it accurate enough? Clin Transl Oncol 20(5):576–583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-017-1749-4

Hjalm-Eriksson M, Lennernas B, Ullen A, Johansson H, Hugosson J, Nilsson S, Brandberg Y (2015) Long-term health-related quality of life after curative treatment for prostate cancer: a regional cross-sectional comparison of two standard treatment modalities. Int J Oncol 46(1):381–388. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2014.2734

Wahlgren T, Brandberg Y, Haggarth L, Hellstrom M, Nilsson S (2004) Health-related quality of life in men after treatment of localized prostate cancer with external beam radiotherapy combined with (192)ir brachytherapy: a prospective study of 93 cases using the EORTC questionnaires QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PR25. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 60(1):51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.02.004

Forslund M, Nygren P, Ottenblad A, Johansson B (2019) Experiences of a nutrition intervention-a qualitative study within a randomised controlled trial in men undergoing radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Nutr Dietetics. https://doi.org/10.1111/1747-0080.12564

Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, Mason M, Metcalfe C, Walsh E, Blazeby JM, Peters TJ, Holding P, Bonnington S, Lennon T, Bradshaw L, Cooper D, Herbert P, Howson J, Jones A, Lyons N, Salter E, Thompson P, Tidball S, Blaikie J, Gray C, Bollina P, Catto J, Doble A, Doherty A, Gillatt D, Kockelbergh R, Kynaston H, Paul A, Powell P, Prescott S, Rosario DJ, Rowe E, Davis M, Turner EL, Martin RM, Neal DE (2016) Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 375(15):1425–1437. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1606221

Design

The present study is a multicentre RCT with follow-up until 24 months after RT completion. The trial was not registered in a clinical trial registry since this routine was not established at our unit at the time of planning this study. However, the NI and the outcome measures are identical to a previous RCT from our research group, which is referred to in the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University This RCT was funded by the Swedish Cancer Society, CAN 2008/799, the Faculty of Medicine at Uppsala University and Uppsala-Örebro Regional Research Council, RFR 386491.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden, approved the study, Dnr 2009/209), and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 24 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Forslund, M., Ottenblad, A., Ginman, C. et al. Effects of a nutrition intervention on acute and late bowel symptoms and health-related quality of life up to 24 months post radiotherapy in patients with prostate cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 28, 3331–3342 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05182-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05182-5