Abstract

Purpose

A growing number of patients with brain metastases (BM) are being treated with stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), and the importance of evaluating the impact of SRS on the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in these patients has been increasingly acknowledged. This systematic review summarizes the current knowledge about the HRQoL of patients with BM after SRS.

Methods

We searched EMBASE, Medline Ovid, Web-of-Science, the Cochrane Database, PsycINFO Ovid, and Google Scholar up to November 15, 2018. Studies in patients with BM in which HRQoL was assessed before and after SRS and analyzed over time were included. Studies including populations of several types of brain cancer and/or several types of treatments were included if the results for patients with BM and treatment with SRS alone were described separately.

Results

Out of 3638 published articles, 9 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included. In 4 out of 7 studies on group results, overall HRQoL of patients with BM remained stable after SRS. In small study samples of longer-term survivors, overall HRQoL remained stable up to 12 months post-SRS. Contradictory results were reported for physical and general/global HRQoL, which might be explained by the different questionnaires that were used.

Conclusions

In general, SRS does not have significant negative effects on patients’ overall HRQoL over time. Future research is needed to analyze different aspects of HRQoL, differences in individual changes in HRQoL after SRS, and factors that influence these changes. These studies should take into account several methodological issues as discussed in this review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Brain metastases (BM) originate from a malignancy outside the central nervous system. Most patients diagnosed with BM have primary lung cancer, breast cancer, or melanoma [1, 2]. Partly due to improved imaging such as MRI and improved systemic treatment of the primary cancer, the number of patients with BM is increasing [3,4,5,6,7].

Traditionally, most patients with BM have been treated with whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) [3, 8, 9]. However, due to advances in the technology, and the increased availability, of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) and concerns about the long-term side effects of WBRT, radiation treatment is shifting toward SRS [3, 10,11,12]. The high precision of SRS spares healthy brain tissue, reducing the risks of long-term side effects [13, 14]. Although SRS is usually delivered in one fraction, it can be delivered in up to five fractions using a linear accelerator, particle beam accelerator or multisource Cobalt-60 unit [15].

Although the prognosis still remains poor [16,17,18], life expectancy in patients with BM is increasing due to improvements in systemic treatments of the primary tumor [6, 19]. Therefore, maintaining a good health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as long as possible is an important [20] primary objective in this patient group [21]. Consequently, management of BM is no longer focused solely on survival, but also on HRQoL and cognitive functioning of patients with BM after treatment [22,23,24].

Authors of previous clinical studies and reviews concluded that future trials that include patients with BM should assess HRQoL as outcome measure, to inform clinical practice (e.g., make informed treatment decisions, assess the efficacy of treatment, and inform patients about HRQoL over time) [21, 23,24,25,26]. In addition, HRQoL is important to evaluate as patients with BM rated HRQoL as the most important factor to be considered in choosing among available treatment options [27], as results from standard assessment of HRQoL in clinical practice may help communication between patients and clinicians [28], and as HRQoL appears to be an independent prognostic factor for survival [29,30,31,32].

To our knowledge, no systematic review has been conducted that focuses primarily on HRQoL outcomes after treatment with SRS alone in patients with BM. A synthesis of the available research findings can help to better understand patients’ HRQoL over time after SRS and can provide directions for future clinical trials. Ultimately, patients and physicians can be better informed on what to expect after SRS in terms of HRQoL. This systematic review summarizes the current knowledge on (changes in) the HRQoL of this patient group after SRS.

Methods

Literature search

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify studies in which adult patients with BM were treated with SRS, and HRQoL was assessed by means of a self-report questionnaire. EMBASE, Medline Ovid, Web-of-Science, the Cochrane Database, PsycINFO Ovid, and Google Scholar were searched up to November 15, 2018. Search terms were verified, and search strategies were built and performed by a biomedical information specialist of the library service of the Erasmus Medical Center, The Netherlands. Studies had to be published as empirical research articles in peer-reviewed journals and written in English, German, or Dutch. Case-report studies were excluded. Studies with an HRQoL assessment before and at least one HRQoL assessment after SRS alone were included. Within-group analyses had to be performed on HRQoL data. Studies that included a heterogeneous sample of patients in terms of type of brain-involved malignancies and/or studies in which different types of treatment were evaluated, were included only if the results for patients with BM treated with SRS alone were reported separately. Inclusion and exclusion criteria in terms of PICOs (patient, intervention, comparison, outcome) and search strategies are presented in Online Resource 1.

Study selection

All studies were screened by the first author (E.V.) based on title and abstract. If eligibility was not clear from the title and abstract, the full text was screened. Papers that potentially met the eligibility criteria after full text screening were also reviewed by the second author (K.G.). Consensus was reached in all cases. This review is a qualitative synthesis of empirical studies. The same two authors extracted data from the included studies and results were compared; there were no disagreements. Reference lists of eligible articles were screened for additional articles.

Assessment of included studies

Factors that were cross-checked and critically evaluated among the studies included the following: type of cohorts/study samples included (e.g., different histologies of primary cancers), prior BM treatment, compliance or reasons for dropout reported, primary endpoints, HRQoL questionnaire used, timing of baseline HRQoL assessment, and timing and place of post-measurements.

Results

Selected studies

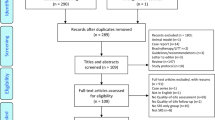

The systematic literature search identified 3638 unique records (Fig. 1). After screening title and abstract, 1290 full texts were considered, and ultimately 9 studies were included in the review (Table 1).

Characteristics of studies

All studies included a heterogeneous group of patients with different primary histologies, except for one study [32], in which only patients with primary lung cancer were included. In one study [40], only geriatric patients (age ≥ 70) were included. In one other study [39], patients were included who already received 3 courses of SRS, whereas in most studies, patients were included before their first course of SRS. Baseline characteristics of patients with baseline HRQoL scores were not reported in two studies [39, 40]. For two studies [33, 36], a proportion of patients was also included in a subsequent study (respectively [32, 37]). Sample sizes in the 9 selected studies ranged from 15 to 97 patients. In most studies, patients were female (range 43.2 to 67.3%), had primary lung cancer (range 37.3 to 100%), and had a median Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score of 80 (range < 70 to 100) (Table 1). In four studies [34,35,36,37], patients with newly diagnosed BM were included; in four other studies [32, 33, 38, 39], patients received prior BM treatment; and in one study [40], it was not reported if patients received prior BM treatment. Reasons for dropout were not reported in 6 studies [32, 34, 35, 38,39,40], and in two studies [36, 37], reasons of dropout were reported, but without the numbers of patients (Table 1).

HRQoL assessments

Results on HRQoL over time of all reviewed studies are presented in Table 1. In three [32, 33, 38] out of nine studies, HRQoL was the primary outcome measure. Four studies [32, 33, 38, 39] evaluated HRQoL both at the group level and at the individual level, two studies [35, 36] evaluated HRQoL at the group level only, and two studies [34, 37] evaluated HRQoL at the individual level only. In the studies reviewed, HRQoL was measured with 5 different self-report questionnaires. The most frequently used questionnaire was the brain cancer–specific Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Brain (FACT-Br), used in 4 studies (Table 2). The most commonly investigated aspects of HRQoL at the group level were physical, general/global, social, and emotional aspects. In six studies [32,33,34,35,36,37], cancer-specific HRQoL self-report questionnaires were used to measure HRQoL, and in three studies [38,39,40], generic HRQoL self-report questionnaires were used to measure HRQoL. In two studies [34, 38], an unknown number of patients completed the “pretreatment”/baseline HRQoL measurement after SRS. Follow-up questionnaires were sent by mail in two studies [32, 33], and in the other studies, administration was scheduled to coincide with hospital visits after SRS. In five studies [34, 36,37,38,39], mean HRQoL scores during follow-up were not reported, although in two of them [38, 39], mean HRQoL at patients’ last follow-up were reported (this point is not the same for each patient).

Discussion

The aim of this review was to summarize findings of studies on (changes in) the HRQoL of patients with BM after SRS. Nine studies were included. Conclusions on HRQoL after SRS however should be drawn with caution, as several (methodological) limitations (discussed below) complicate the interpretation of findings. In two studies on individual scores only, stable overall HRQoL was demonstrated in most patients [34, 37]. In four out of seven studies evaluating group scores, overall HRQoL remained stable in patients with BM after SRS [32, 33, 35, 36], even up to 12 months after SRS in small groups of long-term survivors [32, 33]. However, the three other studies found a decline in overall HRQoL after SRS. One of these studies reported a decline in overall HRQoL 6 and 12 months after treatment in an otherwise undefined small subgroup of geriatric patients (age ≥ 70) [40], and two other studies reported a statistically significant decline in overall HRQoL at patients’ last follow-up [38, 39].

These last two studies [38, 39] most likely assessed HRQoL at the point of progressive disease for many patients, as no further follow-up assessments could be completed. As several studies report a decline in HRQoL after progressive disease [31, 33, 36, 41, 42], the occurrence of progressive disease might explain why these two studies found a decline in HRQoL while other studies reported stable HRQoL during multiple follow-up assessments. Differences in negative and stable outcomes might also be due to different patient or treatment characteristics. In one of these studies [39], patients underwent a minimum of three SRS courses before inclusion and patient characteristics were not reported. However, baseline patient and treatment characteristics in the other study [38] were comparable with the baseline characteristics in the studies reporting stable HRQoL after SRS [32, 33, 35, 36].

Although HRQoL scores on the group level appear to remain stable over time, they may mask individual changes in HRQoL. Habets et al. [36] reported stable HRQoL over time on the group level, while analysis of individual results from a portion of the same study sample on a selection of the scales by van der Meer et al. [37] showed that most patients demonstrated both improvements as well as deterioration in different aspects of HRQoL over time. Four other studies [32, 33, 38, 39] evaluated both group and individual changes in HRQoL after SRS. Two studies found stable mean group scores on additional concerns over time, while on the individual level, the majority of patients (60%) reported less additional concerns [32] and small groups of patients (23 to 36%) reported more additional concerns 1 month after SRS [32, 33]. Two other studies that investigated HRQoL at patients’ last follow-up (median HRQoL follow-up 12 and 19 months) found a decline in group scores on overall health state and self-perceived health state, whereas on the individual level, similar and substantial percentages of patients improved (overall health state, 24% versus 45%; and self-perceived health state, 41% versus 45%) and declined (overall health state, 28% versus 48%; and self-perceived health state, 50% versus 54%) [38, 39]. Differences in the percentages of improved and declined overall health states between both studies may be explained by chance due to the small sample size (n = 27) in one of these studies [39]; in addition, patients in this study had already undergone a minimum of three SRS courses before inclusion in the study.

Similarly, combining the multidimensional aspects of HRQoL, including physical, social, and emotional functioning [43], into a single overall HRQoL score may also lead to a loss of information or mask potential improvements and declines in more specific aspects of HRQoL. One study [34] evaluated an overall HRQoL score only, limiting conclusions about the full range of potentially different HRQoL effects. However, preselecting certain HRQoL subscales based on existing literature and/or clinical insights is a more conservative approach than assessing a wide range of HRQoL outcomes which might lead to potential problems with type I errors in statistical testing due to multiple comparisons.

At the group level, the most frequently evaluated aspects of HRQoL were physical, general/global, social, and emotional aspects. Mean scores of these aspects remained stable over time [32, 33, 35, 36], except for physical well-being/functioning and general/global HRQoL. On these aspects, contradictory results were reported. Three studies using the EORTC-QLQ-C30 or EQ-5D reported a decline in the physical aspect of HRQoL [36, 38, 39], while 3 other studies using the FACT-Br reported stable scores over time [32, 33, 35]. This can be explained by the different questionnaires that were used. For example, the subscale physical functioning of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and the subscales mobility, self-care, and usual-activities of the EQ-5D are more focused on physical activities, while the subscale physical well-being of the FACT-Br is more focused on physical symptoms. It should be noted in addition that declines were reported by the two studies in which HRQoL was assessed at a patients’ last follow-up. This might also explain the difference in findings among studies on general/global HRQoL; the two studies measuring HRQoL at patients’ last follow-up reported a decline [38, 39], while four other studies reported stable scores [32, 33, 35, 36]. However, the different setup in questionnaires might also play a role. Since there is no standard assessment tool for HRQoL in patients with BM, comparing results from studies using different HRQoL measurements remains a challenge [23, 24].

It should be noted that in two studies [34, 38] an unknown number of patients completed the pretreatment HRQoL measurement after SRS, which may have affected conclusions on HRQoL over time. In addition, in five studies [34,35,36,37, 40], previous treatments directed at the BM could have negatively affected the HRQoL of the patients. In two studies [32, 33], follow-up questionnaires were sent by mail; consequently, it was not known whether patients completed the self-report questionnaire themselves without the influence of significant others. On the other hand, patients could fill out these questionnaires at home, which may cause less stress or anxiety compared with the other studies, in which questionnaires were administered in the hospital at control visits, and thus provide a more realistic representation of HRQoL in daily life.

Among the other methodological limitations of studies on HRQoL after SRS was the lack of (reporting of) within-group analyses. To investigate changes in HRQoL after SRS, within-group analyses are needed to be able to draw conclusions on the effect of SRS on HRQoL over time. Unfortunately, several studies did not perform such analyses or did not report the results [31, 42, 44,45,46] and were therefore not included in this review.

When interpreting results from longitudinal studies on HRQoL after SRS, it is important to be aware that a range of other factors, besides the treatment of interest, may influence HRQoL over time, including medication use (e.g., steroids), effects of treatment for the primary tumor (including chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation, surgery), pseudo-progression or progression of disease, HRQoL before treatment, cognitive symptoms, and the mere passage of time. For example, low mood after the diagnosis of BM may be alleviated by the use of an antidepressant or just passage of time. In four of the included studies, factors that affected (changes in) HRQoL after SRS were evaluated. These studies suggested that HRQoL after SRS was associated with KPS, total tumor volume in the brain, symptomatic BM, time since SRS, and disease progression (e.g., intra- and extracranial tumor activity) [32, 33, 36, 38], while the number of BM, sex, and age did not appear to influence HRQoL [32, 33, 36]. However, due to differences between these studies in statistical techniques employed (univariate and multivariate), differences in the choice as to which predictors were investigated and at which time points, it was not possible to draw reliable conclusions.

In addition, a potential effect of “response shift” should be considered. A response shift refers to changes in patients’ internal standards, values, and conceptualization of HRQoL that may occur during the course of their disease [47,48,49,50]. Studies have shown that although the clinical health status of patients with cancer might deteriorate considerably over time, HRQoL scores often remain stable [47]. Most of the studies reviewed did not find considerable deterioration of HRQoL, which may be (partly) explained by the response shift phenomenon. However, although patients might have shifted their response pattern over time, their self-reported HRQoL may still reflect their actual personal interpretation of their HRQoL at a given point in time [51].

High attrition and low response rates are very common in studies that include patients whose life expectancy is short [24, 48, 52]. In many of the studies reviewed, the number of patients completing (long-term) follow-up assessments dropped substantially. In most studies, reasons for dropout (e.g., decease, disease progression, personal motivation) were not or only partly described [32, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. As a result, interpretation of results is complicated [48], and results might not be generalizable to the whole population of patients [53]. However, if the reasons for dropout are related to the disease (progression or death), rather than personal motivation, the results still are very informative with respect to the subgroup of patients who survive on the longer term. Reporting the reasons for dropout is therefore very important for proper interpretation of study results.

The timing of follow-up measurements varied across the studies reviewed and only 3 studies [32, 33, 40] had follow-up periods longer than 6 months; in two other studies [38, 39], HRQoL was assessed at last follow-up, which differed for each patient.

Several limitations of the review process should be noted as well. Abstract screening was carried out by only one author, and thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that one or more additional relevant articles might have been identified if another author had been involved in this screening process. However, we believe that the screening process as carried out was very thorough. It is also possible that relevant studies were excluded due to language constraints. A risk of publication bias cannot be ruled out, since, for example, gray literature was not included in this review.

Future research

The synthesis of the findings of the nine relevant studies revealed that future clinical trials on the effects of SRS on HRQoL of patients with BM are needed to further investigate the multiple aspects of HRQoL over time, individual changes in HRQoL after treatment, and factors that influence HRQoL. Studies should report within-group changes and clearly describe statistical analyses and reasons for dropout. For the assessment of HRQoL in this patient population, brain cancer–specific self-report HRQoL questionnaires, evaluating the different aspects of HRQoL, should be used. To minimize patient burden and therefore prevent high dropout rates, dedicated personnel should be available to administer HRQoL questionnaires, and follow-up HRQoL assessments should be scheduled to coincide with and take place before, instead of after, standard hospital visits after SRS [48, 54]. In addition, more studies with adequate sample sizes at long-term follow-ups (e.g., > 6 months) are needed to analyze different aspects of HRQoL at these time points, especially because irreversible and progressive radiation-induced brain injury, including cognitive impairment, usually emerges > 6 months after treatment [55, 56]. There are many methodological and logistical challenges in performing serial HRQoL assessments in these patients, but the payoff in terms of increased understanding of the effect of both the disease and its treatment on the functional health, symptom burden, and well-being of our patients justifies the additional investment required.

Relevance for clinical practice

HRQoL appears to be an independent prognostic factor for survival in cancer patients with and without BM [29,30,31,32], and in a recent study [27], HRQoL was rated by patients with BM as the most important factor to be considered in choosing among available treatment options. Since more patients with multiple BM are treated with SRS, it is important to know how this treatment may affect the HRQoL of patients over time. In general, results of the studies reviewed here suggest that SRS does not have a significant negative effect on patients’ overall HRQoL over time (even up to 12 months after SRS). This indicates that, in terms of HRQoL, SRS can be safely used in the management of patients with BM. Although more research is needed on factors influencing HRQoL of patients with BM, the current evidence suggests that clinicians should pay additional attention to patients with low KPS, large tumor volumes, symptomatic BM, and disease progression. In addition, assessment of HRQoL in clinical practice may improve communication between patients and clinicians, is helpful to identify patients’ concerns [28], and helps clinicians to provide patients with personalized information. This emphasizes the importance of incorporating HRQoL measures as a standard part of clinical care in patients with BM.

References

Kaal EC, Niël CG, Vecht CJ (2005) Therapeutic management of brain metastasis. Lancet Neurol 4(5):289–298

Rahmathulla G, Toms SA, Weil RJ (2012) The molecular biology of brain metastasis. J Oncol 2012

Arvold ND, Lee EQ, Mehta MP, Margolin K, Alexander BM, Lin NU, Anders CK, Soffietti R, Camidge DR, Vogelbaum MA, Dunn IF, Wen PY (2016) Updates in the management of brain metastases. Neuro-Oncology 18(8):1043–1065

Gerosa M, Nicolato A, Foroni R (2003) The role of gamma knife radiosurgery in the treatment of primary and metastatic brain tumors. Curr Opin Oncol 15(3):188–196

Hanssens P, Karlsson B, Yeo TT, Chou N, Beute G (2011) Detection of brain micrometastases by high-resolution stereotactic magnetic resonance imaging and its impact on the timing of and risk for distant recurrences. J Neurosurg 115(3):499–504

Nayak L, Lee EQ, Wen PY (2012) Epidemiology of brain metastases. Curr Oncol Rep 14(1):48–54

Soffietti R, Ruda R, Trevisan E (2008) Brain metastases: current management and new developments. Curr Opin Oncol 20(6):676–684

McTyre E, Scott J, Chinnaiyan P (2013) Whole brain radiotherapy for brain metastasis. Surg Neurol Int 4(Suppl 4):S236–S244

Barani IJ, Larson DA, Berger MS (2013) Future directions in treatment of brain metastases. Surg Neurol Int 4(Suppl 4):S220–S230

Tsao MN (2015) Brain metastases: advances over the decades. Annals of palliative medicine 4(4):225–232

Soliman H, Das S, Larson DA, Sahgal A (2016) Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) in the modern management of patients with brain metastases. Oncotarget 7(11):12318–12330

Brown PD, Ahluwalia MS, Khan OH, Asher AL, Wefel JS, Gondi V (2017) Whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases: evolution or revolution? Journal of Clinical Oncology. JCO. 2017(2075):9589

Abe E, Aoyama H (2012) The role of whole brain radiation therapy for the management of brain metastases in the era of stereotactic radiosurgery. Curr Oncol Rep 14(1):79–84

Suh JH (2010) Stereotactic radiosurgery for the management of brain metastases. N Engl J Med 362(12):1119–1127

Barnett GH, Linskey ME, Adler JR, Cozzens JW, Friedman WA, Heilbrun MP, Lunsford LD, Schulder M, Sloan AE, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, Congress of Neurological Surgeons Washington Committee Stereotactic Radiosurgery Task Force (2007) Stereotactic radiosurgery—an organized neurosurgery-sanctioned definition. J Neurosurg 106(1):1–5

Gavrilovic IT, Posner JB (2005) Brain metastases: epidemiology and pathophysiology. J Neuro-Oncol 75(1):5–14

Li B, Yu J, Suntharalingam M, Kennedy AS, Amin PP, Chen Z, Yin R, Guo S, Han T, Wang Y, Yu N, Song G, Wang L (2000) Comparison of three treatment options for single brain metastasis from lung cancer. Int J Cancer 90(1):37–45

Suh JH, Chao ST, Angelov L, Vogelbaum MA, Barnett GH (2011) Role of stereotactic radiosurgery for multiple (> 4) brain metastases. J Radiosurg SBRT 1(1):31–40

Jensen CA, Chan MD, McCoy TP, Bourland JD, DeGuzman AF, Ellis TL et al (2011) Cavity-directed radiosurgery as adjuvant therapy after resection of a brain metastasis. J Neurosurg 114(6):1585–1591

Pham A, Lo SS, Sahgal A, Chang EL (2016) Neurocognition and quality-of-life in brain metastasis patients who have been irradiated focally or comprehensively. Expert Review of Quality of Life in Cancer Care 1(1):45–60

Soffietti R, Kocher M, Abacioglu UM, Villa S, Fauchon F, Baumert BG et al (2012) A European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial of adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation in patients with one to three brain metastases from solid tumors after surgical resection or radiosurgery: quality-of-life results. J Clin Oncol 31(1):65–72

Chiu L, Chiu N, Zeng L, Zhang L, Popovic M, Chow R, Lam H, Poon M, Chow E (2012) Quality of life in patients with primary and metastatic brain cancer as reported in the literature using the EORTC QLQ-BN20 and QLQ-C30. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research 12(6):831–837

Witgert ME, Meyers CA (2011) Neurocognitive and quality of life measures in patients with metastatic brain disease. Neurosurg Clin N Am 22(1):79–85

Wong J, Hird A, Kirou–Mauro, A., Napolskikh, J., & Chow, E. (2008) Quality of life in brain metastases radiation trials: a literature review. Curr Oncol 15(5):25–45

Pinkham MB, Sanghera P, Wall G, Dawson B, Whitfield GA (2015) Neurocognitive effects following cranial irradiation for brain metastases. Clin Oncol 27(11):630–639

Kirkbride P, Tannock IF (2008) Trials in palliative treatment—have the goal posts been moved? Lancet Oncol 9(3):186–187

Zeng KL, Raman S, Sahgal A, Soliman H, Tsao M, Wendzicki C et al (2017) Patient preference for stereotactic radiosurgery plus or minus whole brain radiotherapy for the treatment of brain metastases. Annals of palliative medicine 6(2):S155–S160

Jacobsen, P. B., Davis, K., & Cella, D. (2002). Assessing quality of life in research and clinical practice. Oncology, 16(9; SUPP/10), 133–140.

Gotay CC, Kawamoto CT, Bottomley A, Efficace F (2008) The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 26(8):1355–1363

Coates A, Thomson D, McLeod G, Hersey P, Gill P, Olver I et al (1993) Prognostic value of quality of life scores in a trial of chemotherapy with or without interferon in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma. Eur J Cancer 29(12):1731–1734

Pan H-C, Sun M-H, Chen CC-C, Chen C-J, Lee C-H, Sheehan J (2008) Neuroimaging and quality-of-life outcomes in patients with brain metastasis and peritumoral edema who undergo Gamma Knife surgery. J Neurosurg 109(6):90–98

Bragstad S, Flatebø M, Natvig GK, Eide GE, Skeie GO, Behbahani M et al (2017) Predictors of quality of life and survival following Gamma Knife surgery for lung cancer brain metastases: a prospective study. J Neurosurg:1–13

Skeie BS, Eide GE, Flatebø M, Heggdal JI, Larsen E, Bragstad S, Pedersen PH, Enger PØ (2017) Quality of life is maintained using Gamma Knife radiosurgery: a prospective study of a brain metastases patient cohort. J Neurosurg 126(3):708–725

Chang EL, Wefel JS, Maor MH, Hassenbusch SJ III, Mahajan A, Lang FF et al (2007) A pilot study of neurocognitive function in patients with one to three new brain metastases initially treated with stereotactic radiosurgery alone. Neurosurgery 60(2):277–284

Kirkpatrick JP, Wang Z, Sampson JH, McSherry F, Herndon JE, Allen KJ et al (2015) Defining the optimal planning target volume in image-guided stereotactic radiosurgery of brain metastases: results of a randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 91(1):100–108

Habets EJJ, Dirven L, Wiggenraad RG, Verbeek-de Kanter A, Lycklama à Nijeholt, G. J., Zwinkels, H., et al. (2016) Neurocognitive functioning and health-related quality of life in patients treated with stereotactic radiotherapy for brain metastases: a prospective study. Neuro-Oncology 18(3):435–444

van der Meer, P. B., Habets, E. J., Wiggenraad, R. G., Verbeek-de Kanter, A., à Nijeholt, G. J. L., Zwinkels, H., et al. (2018). Individual changes in neurocognitive functioning and health-related quality of life in patients with brain oligometastases treated with stereotactic radiotherapy. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 1–10.

Miller JA, Kotecha R, Barnett GH, Suh JH, Angelov L, Murphy ES, Vogelbaum MA, Mohammadi A, Chao ST (2017) Quality of life following stereotactic radiosurgery for single and multiple brain metastases. Neurosurgery 81(1):147–155. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyw166

Kotecha R, Damico N, Miller JA, Suh JH, Murphy ES, Reddy CA, Barnett GH, Vogelbaum MA, Angelov L, Mohammadi AM, Chao ST (2017) Three or more courses of stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with multiply recurrent brain metastases. Neurosurgery 80(6):871–879

Randolph DM, McTyre E, Klepin H, Peiffer AM, Ayala-Peacock D, Lester S, Laxton AW, Dohm A, Tatter SB, Shaw EG, Chan MD (2017) Impact of radiosurgical management of geriatric patients with brain metastases: Clinical and quality of life outcomes. J Radiosurg SBRT 5(1):35–42

Muacevic A, Wowra B, Siefert A, Tonn J-C, Steiger H-J, Kreth FW (2008) Microsurgery plus whole brain irradiation versus Gamma Knife surgery alone for treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized controlled multicentre phase III trial. J Neuro-Oncol 87(3):299–307

DiBiase SJ, Chin LS, Ma L (2002) Influence of gamma knife radiosurgery on the quality of life in patients with brain metastases. Am J Clin Oncol 25(2):131–134

Chen E, Nguyen J, Zhang L, Zeng L, Holden L, Lauzon N et al (2012) Quality of life in patients with brain metastases using the EORTC QLQ-BN20 and QLQ-C30. J Radiat Oncol 1(2):179–186

Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR, Allen PK, Lang FF, Kornguth DG, Arbuckle RB, Swint JM, Shiu AS, Maor MH, Meyers CA (2009) Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 10(11):1037–1044

Koo K, Kerba M, Zeng L, Zhang L, Chen E, Chow E et al (2013) Quality of life in patients with brain metastases receiving upfront as compared to salvage stereotactic radiosurgery using the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL and the EORTC QLQ BN20+ 2: a pilot study. J Radiat Oncol 2(2):217–224

Brown PD, Jaeckle K, Ballman KV, Farace E, Cerhan JH, Anderson SK, Carrero XW, Barker FG 2nd, Deming R, Burri SH, Ménard C, Chung C, Stieber VW, Pollock BE, Galanis E, Buckner JC, Asher AL (2016) Effect of radiosurgery alone vs radiosurgery with whole brain radiation therapy on cognitive function in patients with 1 to 3 brain metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 316(4):401–409

Sprangers MA (2002) Quality-of-life assessment in oncology. Acta Oncol 41(3):229–237

Lin NU, Wefel JS, Lee EQ, Schiff D, van den Bent MJ, Soffietti R et al (2013) Challenges relating to solid tumour brain metastases in clinical trials, part 2: neurocognitive, neurological, and quality-of-life outcomes. A report from the RANO group. Lancet Oncol 14(10):e407–e416

Dirven L, Reijneveld JC, Aaronson NK, Bottomley A, Uitdehaag BM, Taphoorn MJ (2013) Health-related quality of life in patients with brain tumors: limitations and additional outcome measures. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 13(7):359

Schwartz CE, Bode R, Repucci N, Becker J, Sprangers MA, Fayers PM (2006) The clinical significance of adaptation to changing health: a meta-analysis of response shift. Qual Life Res 15(9):1533–1550

Ubel PA, Peeters Y, Smith D (2010) Abandoning the language of “response shift”: a plea for conceptual clarity in distinguishing scale recalibration from true changes in quality of life. Qual Life Res 19(4):465–471

Leung A, Lien K, Zeng L, Nguyen J, Caissie A, Culleton S, Holden L, Chow E (2011) The EORTC QLQ-BN20 for assessment of quality of life in patients receiving treatment or prophylaxis for brain metastases: a literature review. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research 11(6):693–700

Dirven L, Koekkoek JA, Reijneveld JC, Taphoorn MJ (2016) Health-related quality of life in brain tumor patients: as an endpoint in clinical trials and its value in clinical care. Expert Review of Quality of Life in Cancer Care 1(1):37–44

Lien K, Zeng L, Nguyen J, Cramarossa G, Cella D, Chang E, Caissie A, Holden L, Culleton S, Sahgal A, Chow E (2011) FACT-Br for assessment of quality of life in patients receiving treatment for brain metastases: a literature review. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research 11(6):701–708

Tofilon P, Fike J (2000) The radioresponse of the central nervous system: a dynamic process. Radiat Res 153(4):357–370

Greene-Schloesser D, Robbins M, Peiffer AM, Shaw E, Wheeler KT, Chan MD (2012) Radiation-induced brain injury: a review. Front Oncol 2:73

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Wichor M. Bramer, a biomedical information specialist of the library service of the Erasmus Medical Center, The Netherlands, for the assistance in building and performing search strategies used for this systematic review.

Funding

This study was funded by ZonMw, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (project numbers 842003006 and 842003008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Verhaak, E., Gehring, K., Hanssens, P.E.J. et al. Health-related quality of life in adult patients with brain metastases after stereotactic radiosurgery: a systematic, narrative review. Support Care Cancer 28, 473–484 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05136-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05136-x