Abstract

Objective

To assess the association between gastro-intestinal (GI) symptoms and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in ovarian cancer (OC) survivors.

Methods

Women diagnosed with OC between 2000 and 2010 as registered in the Netherlands cancer registry (n = 348), received a questionnaire on socio-demographic characteristics, HRQoL (EORTC-QLQ-C30), ovarian cancer-specific symptoms including GI (EORTC-QLQ OV28), and psychological distress (HADS). Data collection took place in 2012.

Results

Of 348 women diagnosed with ovarian cancer, 191 (55%) responded. Of all participants, 69% were eligible for analysis (n = 131). In 25% of all women, high level GI symptoms occurred (n = 33). In 23% of all women, recurrence of OC occurred (n = 30). Regression analysis showed that presence of high levels of GI symptoms during survivorship was associated with lower functioning on all HRQoL domains (except for emotional functioning), more symptoms, and higher levels of distress. QoL was negatively affected in those who had few and high levels of GI symptoms. QoL of those with recurrent disease was worse than those without recurrent disease.

Conclusion

A substantial proportion of OC survivors experience GI symptoms, regardless of the recurrence of disease. Health care professionals should be aware of GI symptoms during survivorship in order to refer their patients for supportive care interventions to reduce symptoms or help survivors to cope. Further research should examine the cause of GI symptoms during OC survivorship among those with non-recurrent disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the third most common gynecological malignancy worldwide and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death among women [1, 2]. In the Netherlands, about 1300 cases of OC are diagnosed annually [3, 4]. Due to vague nature of symptoms, the disease is usually diagnosed at an advanced disease stage: up to 70% of all patients is diagnosed with stage III/IV disease, with extensive involvement of the abdominal cavity [5, 6]. Up to 70% of all patients experience recurrent disease [7, 8].Overall, the most frequently reported symptoms at time of OC diagnosis and eventual recurrence are pain, abdominal swelling or distension, unusual fatigue, bloating, weight change, dyspepsia, vomiting, altered bowel habits, urinary, and gastro-intestinal (GI) symptoms [5, 9,10,11]. Standard therapy consists of surgery and chemotherapy [12]. Despite effective initial treatment, overall 5-year survival rates fluctuate from 90% for early-stage disease to 40% for late-stage disease [6, 13].

Some OC survivors may return to their normal functioning and life after the initial treatment, but others survivors will experience a wide range of sequelae related to cancer or its treatment that do not dissipate with time and may result in diminished post-treatment functioning [9, 10].

The most frequently reported problems among OC survivors are fatigue, pain, neuropathy, and concerns about getting cancer under control, recurrence, and death [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Two recent studies revealed that GI symptoms are a common problem among OC survivors who underwent surgery alone or surgery followed by chemotherapy [12, 16]. Research among survivors of other cancer types who received abdominal radiotherapy revealed that up to 40% reported moderate or severe GI symptoms, which had a negative impact on their health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [20]. GI symptoms are commonly reported as symptoms at first presentation of OC or disease recurrence; experiencing these symptoms during survivorship may cause significant distress and deteriorated HRQoL among OC survivors as these symptoms remind them of their disease [21]. However, up to now, no studies address this issue in population-based cohort of both short- and long-term cancer survivors. Therefore, the aims of this study were to assess (1) the prevalence of GI symptoms stratified by recurrence status and (2) the relationship of GI symptoms with HRQoL and distress among OC survivors.

Methods

Setting and participants

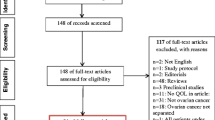

A cross-sectional study was conducted among women diagnosed with ovarian cancer between January 1, 2000 and July 1, 2010, as registered in the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR), in six hospitals in the southern region of the Netherlands. To be eligible, women had to have been diagnosed with ovarian cancer between January 1, 2000 and July 1, 2010, have an adequate literacy level to understand the questionnaire, speak and understand Dutch, have been treated in one of the affiliated hospitals, and had to be alive at the time of the study. Vital status was established either by the hospital patient file or by linking the NCR with the Central Bureau of Genealogy; 693 were deceased according to the Central Bureau of Genealogy and therefore excluded. Of 1147 registered women, 693 were identified as deceased according to the Central Bureau of Geneology and 106 were identified as deceased, hospitalized, or staying in a nursing home according to the hospital patient file. The remaining 348 received a questionnaire (Fig. 1). This study was approved by a regional ethical committee (St. Elisabeth Hospital, no. 1149).

Procedures/data collection

All patients received an information letter from their gynecologist, and after signing the informed consent form about linking the results of the questionnaires with the NCR data, the questionnaires were completed. Data collection took place in 2012 and was done within PROFILES (Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship). PROFILES is a registry to study the physical and psychosocial impact of cancer and its treatment in a dynamic, growing population-based cohort of both short- and long-term cancer survivors. PROFILES contains a large web-based component and is linked directly to clinical data from the NCR. Details of the data collection method have been previously described [22]. Data from the PROFILES registry are available for non-commercial scientific research, subject to study question, privacy and confidentiality restrictions, and registration (www.profilesregistry.nl).

Measures

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

Clinical and patient information was obtained from the NCR (i.e., date of birth, date of diagnosis, disease stage, and primary treatment) [23]. The questionnaire included questions on socio-demographic characteristics (i.e., marital status, employment status, and educational level). Comorbidity at the time of survey was assessed using the self-administered comorbidity questionnaire (SCQ) [24].

HRQoL

The EORTC QLQ-C30 version 3.0 (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life, quality of life core questionnaire) was used to assess HRQoL [25]. It contains five functional scales on physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social functioning, a global health status/QoL scale; three symptom scales on fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and pain; and six single items. The questions were framed as “during the past week…”. Response scales included: “Not at all,” “A bit,” “Quite a bit,” and “Very much,” except for the global QoL scale, which ranges from “Very poor” to “Excellent.” Scores were linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale [26].

Presence of GI symptoms

Disease-specific HRQoL, including GI symptoms, were assessed with the EORTC QLQ-OV28 (Ovarian cancer module) [27]. The QLQ-OV28 module contains seven scales: abdominal/gastrointestinal symptoms, peripheral neuropathy, other chemotherapy side effects, hormonal/menopausal symptoms, body image, attitude to disease/treatment and sexual functioning. Abdominal symptoms are abdominal pain, feeling bloated, clothes too tight, changed bowel habit, flatulence, fullness when eating, indigestion. Peripheral neuropathy symptoms are tingling, numbness, and weakness. Other chemotherapy-related side effects are hair loss and upset by hair loss, taste change, muscle pain, hearing problem, urinary frequency, and skin problems. Hormonal/menopausal symptoms are hot flashes and night sweat. Body image-related symptoms are feeling less attractive and dissatisfied with the body. Attitude towards disease and treatment are described using disease burden, treatment burden, and worry about future. Symptoms of sexual dysfunctioning are rated using interest in sex, sexual activity, enjoyment of sex, and lubrication [27, 28].

The GI symptoms scale consists of six questions: “Did you have abdominal pain?,” “Did you have a bloated feeling in your abdomen/stomach?,” “Did you have problems with your clothes feeling too tight,” “Did you experience change in bowel habit as a result of your disease and treatment,” “Were you troubled by passing wind/gas/flatulence” and “Did you feel full too quickly after beginning to eat.” The questions were framed as “during the past week…”. Response scales included “Not at all,” “A bit,” “Quite a bit,”, and “Very much.” Scores were linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale [26]. Our data revealed a Cronbach’s alphas of 0.80 for the GI symptom subscale.

Psychological distress

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to assess psychological distress. The HADS is a 14-item, self-report measure of anxiety and depression [29, 30]. Each item is rated on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). The HADS has two subscales (anxiety and depression) and a total score. Meta-analysis of Norton et al. showed that the HADS does not provide good separation between the subscales anxiety and depression [31]. Therefore, we only used the total score to describe the psychological distress of the patients [32]. Higher scores imply more psychological distress.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Multi-item scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 were only computed if at least half of the items from a scale were completed, according to the EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring guidelines [24].

The GI symptom scale was dichotomized as 0 to 30 (high level of GI symptoms) versus ≥ 30 to 100 (low level of GI symptoms). This conservative cut-off point was pragmatically chosen.

Frequencies and percentages were used to summarize categorical data. Means and standard deviations were used to summarize continuous data. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who had GI symptoms during survivorship versus those who had lower levels of GI symptoms were compared using independent samples t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables (Table 1).

Descriptives of items of the GI symptom scale were presented stratified by patients with versus those without recurrent disease and were compared using t tests for continuous and chi-square tests for categorical variables (Fig. 2).

Descriptives were presented for the total group (Table 2). Patients who had high levels of GI symptoms during survivorship versus those who had low levels of GI symptoms were compared using t tests for continuous and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Thereafter, clinically important differences were determined between the low and high GI symptom groups based upon published guidelines for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and upon Norman’s rule of thumb for the OV-28 questionnaire [33]. Norman’s rule of thumb states that differences between groups of half a SD or more can be regarded clinically significant [34]. Descriptives were presented stratified by patients with versus those without recurrent disease (supplement Table 3).

Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to evaluate the association between low or high level of GI symptoms (dichotomized item) and the HRQoL scales (dependent variable). A priori we included presence of recurrent disease (no vs. yes), total psychological distress (total score on HADS), presence of comorbidities (no vs. yes), time since diagnosis (years), and age at time of questionnaire completion (years) as confounders.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 348 OC survivors, 191 responded to the questionnaire (55%, Fig. 1). Sixty women (17%) were excluded due to lacking information on the presence of recurrent disease, 131 participants were eligible for analysis (38% of the invited patients, 69% of the respondents) of which 101 (77%) had non-recurrent disease and 30 (23%) experienced recurrent disease. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics did not differ between patients with high and low levels of GI symptoms (Table 1).

GI symptoms

Twenty five percent of the patients (n = 33) reported high levels of GI symptoms (Table 1). Of the 101 patients who had non-recurrent disease, 20 (20%) experienced high levels of GI symptoms, while 13 of the 30 (43%) patients with recurrent disease experienced high levels GI symptoms. Women who were suffering from recurrent disease more often significantly experienced high levels of GI symptoms (odds ratio 6.3 p = 0.01; not tabulated) and scored significantly higher on three (presence of abdominal pain, bloated feeling, and change in bowel habits) of six of the GI symptom items (Fig. 2).

HRQOL domains of functioning and symptoms

Descriptive statistics on HRQoL scores were tabulated for the total group (Table 2) and stratified for patients with versus those without recurrent disease (Supplement Table 3).

In univariate analyses, significant differences were found between survivors with high and low levels of GI symptoms in all HRQoL functional scales (Table 2). Furthermore, patients suffering from high level of GI symptoms reported a worse overall QoL (p = 0.00) and higher levels of (cancer-related) symptoms (0.00 ≤ p ≤ 0.04). Lastly, patients suffering from GI symptoms more often had distress (p = 0.00) compared to those without GI problems. All differences were of small to large clinical importance. Descriptives of recurrent versus non recurrent disease have been described in supplement Table 3. Presence of recurrent disease in those with high levels of GI symptoms did not change the levels of HRQoL (functioning and symptoms) or distress. In those with low levels of GI symptoms with recurrent disease, HRQoL scores revealed to be worse compared to those with high level of GI symptoms and recurrent disease (supplement Table 3).

In multivariate analyses, patients with higher levels of GI symptoms scored lower on all HRQoL functioning scales and higher on all symptom scales, except emotional functioning (p = 0.15), financial problems (p = 0.67), and sexuality (p = 0.18), compared to patients without GI symptoms.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, 25% of OC survivors reported having high levels of GI symptoms, regardless of presence of recurrent disease. GI symptoms may have an impact on the well-being of survivors because they are debilitating and act as a reminder of disease and treatment [21] and as a presenting symptom for recurrent disease [5, 9, 10]. In line with this, we found that OC survivors without recurrent disease with high GI complaints reported higher levels of distress than patients with low levels of GI symptoms. Those with low levels of GI symptoms and recurrent disease have a worse level of functioning and more symptoms on various domains compared to those with low levels of GI symptoms without recurrent disease or those with high levels of GI symptoms.

Our study adds to the current literature by showing that OC survivors with and without recurrent disease who experience GI complaints reported significantly more symptoms, including fatigue, nausea, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation or diarrhea, hormonal symptoms, neuropathy, and other chemotherapy side effects compared to those without GI complaints. One other study showed that GI symptoms appeared to be moderately correlated with HRQoL including social functioning, pain, and the nausea/vomiting [27]. It is unclear whether these issues are fully due to OC or due to treatment (surgery or chemotherapy) or other physiologic causes.

Our study showed that prevalence of GI symptoms in patients with recurrent disease is higher in those of survivors without recurrent disease. OC survivors with recurrent disease had lower scored on HRQoL scales for global QoL and higher scores on symptom scales. This could be interpreted as side effects of further treatment that patients have to undergo because of recurrent disease. Initial treatment as well as treatment for recurrent OC includes chemotherapy that causes considerable toxicity, such as nausea, vomiting, lack of appetite, alopecia, weakness, and fatigue [35]. Symptoms such as peripheral neuropathy are to a large extent irreversible, while others such as GI symptoms, pain, and fatigue or psychological problems can potentially be treated if identified early [36]. These symptoms usually disappear over time after treatment completion.

GI symptoms were associated with HRQoL, regardless of the presence of recurrent disease. GI complaints might probably be related to the sequelae of the initial treatment consisting of surgery followed by systemic treatment with chemotherapy or recurrent disease. Unfortunately, we did not record specific data on chemotherapeutic regimen, surgical outcome, pre-existent performance status, or complications during treatment as possible explanations for persisting GI symptoms during survivorship.

Clinical implications

Care provided to OC patients should not be stopped when the treatment ends because many women continue to experience complaints after their cancer treatment [36]. During transition from patient to survivor, patients lose contact with their cancer caregiver and they are challenged to resume former roles in life, even while they experience problems [37]. Therefore, symptom management is important to maintain HRQoL of OC survivors. A recently published review [38] showed benefits of interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy and motivational interviewing as effective interventions to help patients to cope with physical and psychological problems, especially for women in whom the presence of GI symptoms acts as a reminder of the disease. As of yet, no instrument for symptom monitoring or interventions for persistent GI symptoms exist, except interventions that reduce burden of sequelae. Therefore, further research after causes of GI symptoms is warranted to uncover possibilities for symptom management and patient consultation.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the current study are that it is a population-based multicenter study design and it uses standardized and validated questionnaires. However, our study also has several limitations. The findings are based on cross-sectional data; this means that causal relationships could not be determined. In a study performed with a longitudinal design, analyses stratified by surgical outcomes would be possible. In addition, the results could have been affected by survivorship bias due to aggressiveness of the disease and low survival rates [39]. Of all selected patients, only 40% was still alive at time of inclusion. Detailed information about the health status of non-respondents is lacking (our response rate was 55% of whom we had to exclude 31% due to lacking data on recurrent disease). Furthermore, analyses on recurrent disease could not be performed due to small numbers of participants. Still, our sample may be considered representative for the OC population: from literature 5-year survival rate is at around 40%, but 90% for early stage disease [6, 13]. Prior research revealed that 10 to 50% of the OC survivors reported GI symptoms [19, 36, 40]. We interpret these differences due to different survival time from previous studies, and we included a heterogeneous population including patients with and without recurrent disease and we excluded those with missing data.

In conclusion, a substantial proportion (20%) of OC survivors experience GI symptoms that are similar to first presentation, despite the fact that a large proportion does not have recurrent disease. Health care professionals should be aware of the persistence of presenting symptoms during survivorship, affecting domains of functioning in daily life.

References

Openshaw MR, Fotopoulou C, Blagden S, Gabra H (2015) The next steps in improving the outcomes of advanced ovarian cancer. Women’s Health (Lond Engl) 11(3):355–367

Palmer J, Gillespie A Palliative care in gynaecological oncology. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med 22(5):123–128

Verkissen MN, Ezendam NPM, Fransen MP, Essink-Bot ML, Aarts MJ, Nicolaije KAH, Vos MC, Husson O (2014) The role of health literacy in perceived information provision and satisfaction among women with ovarian tumors: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Patient Educ Couns 95(3):421–428

IKNL. Nederlandse Kankerregistratie. 2015

Ebell MH, Culp MB, Radke TJ (2016) A systematic review of symptoms for the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Am J Prev Med 50(3):384–394

Rai N, Nevin J, Downey G, Abedin P, Balogun M, Kehoe S, Sundar S (2015) Outcomes following implementation of symptom triggered diagnostic testing for ovarian cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 187:64–69

Mahner S, Burges A (2014) Quality of life as a primary endpoint in ovarian cancer trials. Lancet Oncol 15(4):363–364

Thigpen JT (2015) Contemporary phase III clinical trial endpoints in advanced ovarian cancer: assessing the pros and cons of objective response rate, progression-free survival, and overall survival. Gynecol Oncol 136(1):121–129

Agarwal S, Bodurka DC (2010) Symptom research in gynecologic oncology: a review of available measurement tools. Gynecol Oncol 119(2):384–389

Gosain R, Miller K (2013) Symptoms and symptom management in long-term cancer survivors. Cancer J 19(5):405–409

Sun CC, Bodurka DC, Weaver CB, Rasu R, Wolf JK, Bevers MW, Smith JA, Wharton JT, Rubenstein EB (2005) Rankings and symptom assessments of side effects from chemotherapy: insights from experienced patients with ovarian cancer. Support Care Cancer 13(4):219–227

Westin SN, Sun CC, Tung CS, Lacour RA, Meyer LA, Urbauer DL, Frumovitz MM, Lu KH, Bodurka DC (2016) Survivors of gynecologic malignancies: impact of treatment on health and well-being. J Cancer Surviv 10(2):261–270

Matulonis UA et al (2008) Long-term adjustment of early-stage ovarian cancer survivors. Int J Gynecol Cancer 18(6):1183–1193

Arriba LN, Fader AN, Frasure HE, von Gruenigen VE (2010) A review of issues surrounding quality of life among women with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 119(2):390–396

Carey MS, Gotay C, Gynecologic Cancer I (2011) Patient-reported outcomes: clinical trials in ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 21(4):782–787

Cleeland CS, Rose SL (2015) Symptom management of gynecologic cancers: refocusing on the forest. Gynecol Oncol 136(3):413–414

Guenther J, Stiles A, Champion JD (2012) The lived experience of ovarian cancer: a phenomenological approach. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 24(10):595–603

Lakusta CM, Atkinson MJ, Robinson JW, Nation J, Taenzer PA, Campo MG (2001) Quality of life in ovarian cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 81(3):490–495

Goncalves V (2010) Long-term quality of life in gynecological cancer survivors. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 22(1):30–35

Taylor S, et al. (2016) The three-item ALERT-B questionnaire provides a validated screening tool to detect chronic gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy in cancer survivors. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol)

Smith AB et al (2016) The prevalence, severity, and correlates of psychological distress and impaired health-related quality of life following treatment for testicular cancer: a survivorship study. J Cancer Surviv 10(2):223–233

van de Poll-Franse LV et al (2011) The patient reported outcomes following initial treatment and long term evaluation of survivorship registry: scope, rationale and design of an infrastructure for the study of physical and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivorship cohorts. Eur J Cancer 47(14):2188–2194

Hermanek P (1997) TNM atlas : illustrated guide to the TNM/pTNM classification of malignant tumours. 4th ed. ed., Berlin ; London: Springer

Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN (2003) The self-administered comorbidity questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum 49(2):156–163

Niezgoda HE, Pater JL (1993) A validation-study of the domains of the Core Eortc Quality-of-Life Questionnaire. Qual Life Res 2(5):319–325

Fayers PM (2001) Interpreting quality of life data: population-based reference data for the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur J Cancer 37(11):1331–1334

Greimel E, Bottomley A, Cull A, Waldenstrom AC, Arraras J, Chauvenet L, Holzner B, Kuljanic K, Lebrec K, D’haese S (2003) An international field study of the reliability and validity of a disease-specific questionnaire module (the QLQ-OV28) in assessing the quality of life of patients with ovarian cancer (vol 39, pg 1402, 2003). Eur J Cancer 39(17):2570–2570

Cull, A., , Howat S., Greimel E., Waldenstrom A.C., Arraras J., Kudelka A., Chauvenet L., Gould A., EORTC Quality of Life Group [European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer]., Scottish Gynaecological Cancer Trials Group, Development of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer questionnaire module to assess the quality of life of ovarian cancer patients in clinical trials: a progress report. European Journal of Cancer, 2001. 37(1): p. 47−+, 53

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D (2002) The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale - an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52(2):69–77

Norton S, Cosco T, Doyle F, Done J, Sacker A (2013) The hospital anxiety and depression scale: a meta confirmatory factor analysis. J Psychosom Res 74(1):74–81

Vodermaier A, Millman RD (2011) Accuracy of the hospital anxiety and depression scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 19(12):1899–1908

Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, Martyn St-James M, Fayers PM, Brown JM (2011) Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European organisation for the research and treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. J Clin Oncol 29(1):89–96

Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW (2003) Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life - the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 41(5):582–592

Leppert W, Gottwald L, Forycka M (2015) Clinical practice recommendations for quality of life assessment in patients with gynecological cancer. Prz Menopauzalny 14(4):271–282

Ahmed-Lecheheb D, Joly F (2016) Ovarian cancer survivors’ quality of life: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 10:789–801

Wu HS, Harden JK (2015) Symptom burden and quality of life in survivorship a review of the literature. Cancer Nurs 38(1):E29–E54

Spencer JC, Wheeler SB (2016) A systematic review of motivational interviewing interventions in cancer patients and survivors. Patient Educ Couns 99:1099–1105

Gonçalves, V.n., Quality of Life in Ovarian Cancer Treatment and Survivorship. 2013: InTech

Lind H, Waldenström AC, Dunberger G, al-Abany M, Alevronta E, Johansson KA, Olsson C, Nyberg T, Wilderäng U, Steineck G, Åvall-Lundqvist E (2011) Late symptoms in long-term gynaecological cancer survivors after radiation therapy: a population-based cohort study. Br J Cancer 105(6):737–745

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplement Table 3

(DOCX 36 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rietveld, M.J.A., Husson, O., Vos, M.C.(. et al. Presence of gastro-intestinal symptoms in ovarian cancer patients during survivorship: a cross-sectional study from the PROFILES registry. Support Care Cancer 27, 2285–2293 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4510-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4510-9