Abstract

Purpose

To explore the perspectives of people anticipated to be in their last year of life, family carers, volunteers and staff on the impacts of receiving a volunteer-provided befriending service. Patient participants received up to 12 weeks of a volunteer-provided befriending intervention. Typically, this involved one visit per week from a trained volunteer. Such services complement usual care and are hoped to enhance quality of life.

Methods

Multiple case study design (n = 8). Cases were end-of-life befriending services in home and community settings including UK-based hospices (n = 6), an acute hospital (n = 1) and a charity providing support to those with substance abuse issues (n = 1). Data collection incorporated qualitative thematic interviews, observation and documentary analysis. Framework analysis facilitated within and across case pattern matching.

Results

Eighty-four people participated across eight sites (cases), including patients (n = 23), carers (n = 3), volunteers (n = 24) and staff (n = 34). Interview data are reported here. Two main forms of input were described—‘being there’ and ‘doing for’. ‘Being there’ encapsulated the importance of companionship and the relational dynamic between volunteer and patient. ‘Doing for’ described the process of meeting social needs such as being able to leave the house with the volunteer. These had impacts on wellbeing with people describing feeling less lonely, isolated, depressed and/or anxious.

Conclusion

Impacts from volunteer befriending or neighbour services may be achieved through volunteers taking a more practical/goal-based orientation to their role and/or taking a more relational and emotional orientation. Training of volunteers must equip them to be aware of these differing elements of the role and sensitive to when they may create most impact.

Trial Registration

ISRCTN12929812

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Volunteers and the voluntary sector are increasingly seen as critical in the collective effort to address societal challenges in health and social care as an ageing society creates more demand for public services [1]. Volunteers are important in providing services where public spending is under pressure, but also where new solutions are needed to respond to new needs and enrich communities. This approach brings both challenge and opportunity; whilst there are increasing opportunities for volunteers to contribute to care, there are also expectations that the outcomes and user perceptions of such care should be known, and services transparent and accountable [2].

Volunteers are distinctively different from paid providers, with definitions emphasising the free choice to give unpaid time to benefit others [3, 4]. Whilst such support was traditionally in non-patient facing roles in many countries, care for those with cancer and at the end of life is an area where volunteers are increasingly being used in patient facing roles [2, 5,6,7], especially providing psychosocial care [8,9,10,11].

Most volunteering research in cancer and palliative care focuses on the roles of volunteers, their organisation and training and their experiences, rather than service outcomes or perspectives on care [8, 9, 12, 13]. Studies tend to explore issues such as the volunteer experience [14,15,16], the nature of their role [17], their interaction with professional staff [18], the ethics of working as a volunteer [19] and the impact on their own health [20]. Satisfaction with services has tended to be explored from the perspective of volunteers or the services they work with rather than those of the people who receive care [21,22,23]. Benefits to people who receive care are assumed to include improvements in quality of life and enhancement of wellbeing [6, 9, 23, 24]. Other potential impacts include the impact of services on the survival of those at the end of life [25], and whether health service utilisation costs could be reduced [26]. However, the voice of people who receive care from volunteers is largely absent from research in this field.

Studies are required which examine the impact of volunteer services within cancer and palliative care on care outcomes, and explore patient perceptions of volunteer service provision and its impact. Our own and other volunteering trials are addressing understanding impact in terms of measurable patient outcomes [27,28,29,30], but it is also important to explore patient perspectives on impact and the mechanisms by which this may be achieved.

Methods

Aim

The aim of this paper is to identify and explore patient, carer, volunteer and service provider perceptions of impact of volunteer befriending services provided to those perceived to be in their last year of life. The focus of this paper is primarily patient perceptions of impact, as these are under-represented in existing literature.

Design

The interviews reported here were collected as part of a large mixed-method evaluation of volunteer provided befriending services at the end of life (the End of Life Social Action (ELSA) study) [27,28,29]. The ELSA study included both a wait-list randomised controlled trial and eight qualitative case studies centred on sites providing the service within the trial [31,32,33]. Qualitative case studies incorporated interviews, observation and documentary analysis, but only interview data are reported here.

Setting

Sites were funded to deliver volunteer provided befriending services to people anticipated to be in their last year of life. Eleven sites throughout England participated, primarily hospices, but also an acute hospital trust and charity providing support to those with alcohol and drug use problems. Key elements of the volunteer provided support intervention include its delivery by trained volunteers who provided care tailored to the needs of the individual offered from a suite of options including befriending, practical support and signposting. Volunteer support was typically provided face to face, one on one and in the home, but telephone contact and meeting outside the home were possible. The frequency and length of contact were individually determined, but were typically a visit once a week for 1–3 h.

Sampling and recruitment

Eight sites from the 11 were selected for in-depth qualitative case study work on the basis of size and type of provider organisation and type of befriending service offered. The case is defined as the provision of the end-of-life befriending service within a defined locality by a provider organisation. Data were collected in 2015–16.

Case study participants were patients, family carers, volunteer befrienders and staff. Potential patient participants were those who had already consented to be part of the trial and given permission to be approached about participating in a qualitative interview. Participants in the trial include people anticipated to be in their last year of life and their informal carer (Table 1). At trial inclusion, patient participants were asked to also identify a family member/informal carer to participate. Local site coordinators sampled patient trial participants for the qualitative study to maximise variability in age and gender. Where possible volunteer befrienders were those providing care to patients sampled for qualitative interview, but they were also arbitrarily sampled from the pool of all volunteer befrienders. All site staff were invited to participate. All potential participants were provided with information about the study, and written consent was obtained prior to the interview being conducted, in addition to any existing trial consents. Inclusion criteria were deliberately broad to include typical participants of such services.

Data collection

Single qualitative thematic interviews were conducted with patients, family carers, volunteer befrienders and staff to ascertain experiences and impacts associated with the befriending services. Volunteers and staff reflected on their overall experience, not just associated with patient participants. An interview topic guide was prepared and iteratively developed through the study. The topic guide is summarised in Table 2.

Interviews were audio recorded using encrypted digital recorders and fully transcribed. Transcripts were not returned to participants. Contemporaneous field notes were made. Qualitative data were collected by SD, MH (both male research associates) and CW (female academic): all experienced qualitative researchers. Whilst additional data were collected including non-participant observation of organisational meetings and collection of documentary data such as service policies and job descriptions, these are not reported here.

Data were collected from staff members and volunteers at the case study sites. Data collection with patients and carers took place in patient’s homes. Interviews ranged in length from 11 to 94 min, with a mean length of 37 min.

Data analysis

The five steps of framework analysis facilitated within and cross-case pattern matching: familiarisation, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting and mapping and interpretation [33]. Data displays enabled identification of divergence in responses given by those from different sites and interviewee groups [33, 34]. NVivo 11™ was used to manage data. The initial a priori coding frame mostly mirrored the structure of topic guide used in interviews, developed by SD and MH, and inductive elements were added through the study [SD, MH, CW]. Staff participants had an opportunity to meet after data collection was complete to discuss emerging analysis, and this influenced the final framework. Cross-case pattern matching followed to identify thematic factors associated with perceptions of impact.

Ethical and funding considerations

Health Research Authority research ethics approval was granted 12.3.15 by NRES Committee Yorkshire and the Humber – South Yorkshire, REC reference 15/YH/0090, IRAS project ID 173058. Site-specific approvals were granted by NRES Committee Yorkshire and the Humber – South Yorkshire. This study was funded by the UK Cabinet Office, who had no involvement in the design, data collection or analysis of data.

Availability of data and materials

Patient-level data are stored in the ELSA database developed by the study authors on a secure server maintained by Lancaster University. Presented data are fully anonymised. The corresponding author may be contacted to forward requests for data sharing.

Results

The inputs and impacts of the volunteering service are presented below, as a cross-case analysis, with particular attention paid to patient perceptions of changes (impacts) brought about by the presence of the volunteer in the life of the patient and their family/carer, and the views of volunteers and staff on such perceptions and impacts. Table 3 presents data on the number of participants within each case study site. Table 4 characterises the patient participants, compared to the trial participants from which the sample was drawn. Patients selected for qualitative interview shared typical characteristics of those receiving the service, but with a greater proportion of females.

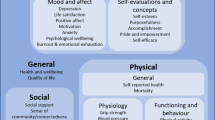

Figure 1 conceptualises the process of impact, demonstrating a temporality to the perception of impact, and dependent on the form of input. The inputs and impacts are described below.

‘Being with’: relationship building input

An agreeable relationship between patient and volunteer and a degree of relational chemistry appeared an important prerequisite for impact. In practical terms, the relational aspects of the volunteer visit were apparent in the opportunity provided for conversation. Conversation was the most common object of patient’s appreciation:

Chatting generally and exchanging viewpoints and all the rest of it; so that’s that. It’s convivial. Friendly conversation, which is what the whole thing was intended to be wasn’t it? … It shouldn’t be a friendship as though it was contrived; it should just naturally develop as it might in ordinary circumstances. (CAS3/PAT/04)

Conversation could involve ‘small talk’ about mundane topics, which may act as a distraction from more weighty concerns that might be preoccupying patients. It could also be a welcome change from conversation with family members who might be overly focused on health-related matters. Wide-ranging conversation was aided by the novelty of the relationship and how little each party initially knew of each other. At the other extreme, conversation could also be valuable to patients when it provided the opportunity for them to speak their mind to someone they could trust about sensitive topics. Most typically, this involved speaking about health concerns.

‘Doing for’: activity input

Of the activities undertaken by volunteers with patients, the opportunity provided to go out was commonly linked by participants to impact. The impacts promoted through this activity could be particularly pronounced when the volunteer has more time for going out than the patient’s family or friends or when the volunteer can take the patient somewhere they would not otherwise be able to visit:

They [volunteer and patient] found themselves in [supermarket] and it was just before Christmas and they came back, I came back and there was [patient name] with a half assembled, really appropriate looking Christmas tree. At a time when we knew we wouldn’t be going anywhere and we knew we would not be visited and felt guilty and unhappy and a little sad at not being able to get the old fashioned things down and put all the lights up. But not wanting it to be an empty, Christmas-free house and it ended up, if anything, a better looking Christmas tree. (CAS6/01/CAR)

Although support to go out was a common component of some services, the impact of this on social support is likely to be particularly high for the subset of patients who would otherwise be unable to go out:

To go out I have got to have somebody with me, I mean when you are getting older it doesn’t mean to say you have stopped going out, but if you are injured, then it does stop you going out without … I have got to have somebody with me, put it like that. (CAS8/01/PAT)

Relationship between input and perceptions of impact

Some impacts, such as those tied up with the opportunity for patient self-expression, appear linked to the relational dynamics between patients and volunteer. In cases where the relationship afforded the opportunity to discuss deeper and more troubling topics, patients reported benefits tied to being able to frankly discuss their thoughts without the fear of worrying family or friends:

If you keep getting bad news thrown at you and then you’ve got to keep it bottled up. You go for these visits to the hospital, you come back home, and you know that night you’re going to be getting text messages and phone calls from everybody, ‘How did it go?’ and you’ve got to do your best to keep it bottled in. Well now, to have someone like [volunteer name] … maybe we meet up the week after, and someone to be able to talk to about it because I keep it to myself. (CAS7/01/PAT)

Unfamiliarity with the volunteer can enable a person to openly speak about problems to somebody they do not know:

Being able to talk about my problems freely to somebody I don’t know. They’re not like that, well [volunteer name]‘s not like that…..I open up talking to a person that doesn’t know me. I open up and that’s it, the floodgate’s open, isn’t it, and everything comes out. (CAS8/02/PAT)

Conversation could also have other wellbeing impacts, including the benefits for the patient of being able to discuss topics that were overly familiar to their other social contacts. This could be important to the patient, allowing them an opportunity to speak regularly about their life story to someone for whom it is unfamiliar. This could be seen as a chance to put their life in context or see it through a fresh pair of eyes:

And perhaps doesn’t want to talk to her family too much about all the past, because they’ve heard it before. I haven’t and I’m quite intrigued. She has some wonderful stories and everybody likes to share a story and to an interested party. (CAS6/01/VOL)

Positive wellbeing effects could emerge both from discussing anxieties and concerns as well as from activities or conversations with the volunteer that enhanced self-worth, often from a greater sense of being cared for due to the volunteer making the effort to contribute their time, energy and interest on a regular basis. Impacts were also reported through more practical help where volunteers allowed patients and carers to achieve what would otherwise be difficult for them resulting in them feeling better about their situation.

The forms that wellbeing impacts took varied from reductions in negative feelings (such as depression and/or loneliness) to growth in confidence. For people who appeared more socially isolated, an impact of conversation or support to go out was the alleviation of loneliness. Staff members within each site were clear that the befriending service helped some patients to reduce their level of isolation. Where patients were experiencing high levels of loneliness, the impacts were perceived to be highest, potentially helping with associated problems such as depression. As a consequence of the service provided, several patients mentioned the relief from loneliness:

With the befriender coming and getting me out, it makes a lot of difference to me because when I'm stuck in here and I don’t get out, because I'm not so well or whether it’s because of the weather or whatever, I get really depressed and really weepy and if I've got [befriender name] to look forward to, knowing if the weather’s fine we can go out and that’s it. It’s getting out is the main thing for me really. (CAS7/03/PAT)

Though wellbeing impacts were not always spelt out, there were examples in which the impact of the service was made clear, such as motivation to do “something positive” and to do more than sitting down “feeling sorry” for oneself:

Sometimes you can’t be bothered or you won’t do things and when somebody else comes and you talk to them and you talk between you, you, realise that you should be doing different things and not just sat and feeling sorry for yourself and things like that, and I feel better when she’s gone because I know she’s been making an effort with me which I feel is a big thing. (CAS8/03/PAT)

Other forms of impact

In addition to the wellbeing impacts promoted by the service, there were other impacts that were promoted by the opportunity to go out, the relationship involved or the presence of an attentive volunteer. Volunteers were generally encouraged to take a versatile and open approach to befriending, increasing the possibility that impact could be created by responding to need. For example, people were supported to participate in hobbies:

We had one gentleman quite early on who used to paint, but had stopped painting, had not painted for a few years. So his volunteer, she is adorable, she just was asking him about what his hobbies were and things, and he was, she said oh well show me some of your paintings … And eventually he started painting again, and he got his volunteer painting. (CAS6/02/STA)

Although the befrienders did not directly intervene in the physical health of the patient, the volunteer could function as a link to other professionals. This might involve supporting their client to attend a medical appointment, requiring them to schedule their visit to coincide with the appointment. Volunteers also played a role in observing the health of their client and updating others on any changes they notice. This is not a substitute for contact with clinical staff, but the lay input of the volunteer could be of value given their frequent and regular contact with the patient:

The volunteer goes in one day and notices they’ve reached crisis point and none of their medications have been taken, the carer has disappeared off and they are not in a good place. That volunteer can call up our specialist services straight away and a clinical nurse specialist can go out or a doctor could go out, or if it was a physio we could get our physio in really quickly. (CAS6/01/STA)

By staying in regular contact with a volunteer, there is the potential that patients with worsening symptoms will access medical services sooner than if they were without the input of the volunteer. This could potentially increase the efficiency of the patient’s use of medical resources by enabling them to access services in a timely way.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Wellbeing appears to be facilitated through two forms of volunteer input. First, ‘being with’ or relationship building enabled the creation of a relational dynamic between patient and volunteer which facilitated open expression. Second, ‘doing for’ or activity efforts enabled a (re) opening of the patient’s world which assisted a sense of participating in a more usual life than previously. These are important impacts on a person’s quality of life and wellbeing, enabled by people-centred ‘small things’.

What this study adds

‘Being with’ and ‘doing for’ are identified in the research of others. Relationship building is usually considered critical to end-of-life care provision [35], although it may not be a necessary prerequisite for good psychosocial care [36]. However, the emotional experience of care is critically important to patients and carers [37]. Social capital is recognised to have an impact on health [38, 39], and a focus on everyday life is known to be an important component of coping well towards the end of life [40]. Social networks can strengthen as death nears [41], befriending services may be an important element in both enabling re-engagement with others and becoming part of a network of care. Our research contributes to this developing understanding of the importance of emotional and social aspects of care.

The evidence on the impact of volunteers on people with cancer or towards the end of life is scant, mostly pointing to satisfaction with services rather than understanding outcomes for those receiving services [42]. Befriending interventions appear to have some benefit on patient wellbeing, but the effect size is small [27, 43]. This could be considered surprising, as there is evidence that the presence of social relationships has a direct impact on health and mortality [26, 44, 45]. Studies of volunteering impact call for a more theoretically informed approach to understanding why volunteers may have an impact and what outcomes could be anticipated from the input of volunteers [42]. Our study provides qualitative data to inform this discussion, pointing towards the importance of understanding the ‘being with’ and ‘doing for’ work of volunteers, and the effects these had on perceptions of wellbeing as impact. The challenge for researchers will be the sensitivity of tools to measure the nuances of these effects in the context of an overall decline in wellbeing and quality of life towards the end of life [27].

This research adds to an understanding of the importance both of person-centred responsive care, and that this need not be always professionally provided to have impact. People towards the end of life respond to those who pay attention to need, whether that be, for example, conversations with cleaning staff [46] or the responsiveness of someone unfamiliar with their care needs [36]. What may be distinctively different about the responsiveness of volunteers in both ‘being there’ and ‘doing for’ is that people also responded to the altruism inherent in the volunteer role, in contrast to the roles of professional care providers. This appeared to enhance perceptions of impact, possibly because social expectations of reciprocity and intention were affected by the voluntary role [47].

Much attention has been given recently to concepts of community involvement in, and the importance of public health approaches to, palliative and end-of-life care [48]. Volunteer befriender services can be seen as part of a response to these calls. Whilst these services could be said to be meeting both personal and population needs [49], the focus is frequently on mobilising networks of care within and across different caring communities of family, friends and the wider community [50]. These findings support the roles of such services in enabling brokerage across ‘holes’ in an individual’s person’s networks [51], whether that be for companionship or practical support, and the impact on people of meeting these non-clinical needs.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This is one of the largest qualitative studies of volunteers providing care towards the end of life and has particular strengths in its focus on the voice of people being supported as well as those of staff or volunteers. Limitations include the data being collected in the context of a trial, participation in which may potentially have influenced people’s views. We also did not recruit family carers in the numbers desired. Selection of patient participants from those within the trial was mediated by service coordinators, to ensure those who were ill or deteriorating were not contacted, and this may have an unknown influence.

Implications for practice and suggestions for future research

Clinicians can support volunteer provided befriending services, as these appear to have emotional and social benefits which clinical services may struggle to provide. This research identifies the domains these services have influence in, and the challenge for future researchers is to identify how to measure impact across these domains to enable targeting of services where resources (e.g. volunteers) may be limited.

Conclusion

Impacts from volunteer befriending or neighbour services may be achieved through volunteers taking a more practical/goal-based orientation to their role and/or taking a more relational and emotional orientation based on conversation, sharing stories and expressing feelings. The exact combination and weighting given to both of these aspects of the role must be determined by the needs of the patient and their relationship with the volunteer. Training of volunteers must equip them to be aware of these differing elements of the role and sensitive to when it is necessary to depend on one facet of the role or the other.

References

Department of Health (2011) Social action for health and well-being: building co-operative communities. Department of Health strategic vision for volunteering. Department of Health, London [available https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/social-action-health-and-well-being-building-co-operative-communities-department-of-health-strategic-vision-for-volunteering. Accessed 5.2.18]

Naylor C, Mundle C; Weaks L; Buck D. (2013) Volunteering in health and care Securing a sustainable future. London

National Council for Volunteering Organisations (2017) Volunteering. National Council for volunteering Organisations. Accessed 04.01.2017 2017

Scott R (2014) Volunteering: vital to our future. How to make the most of volunteering in hospice and palliative care. Hospice UK, London

Burbeck R, Candy B, Low J, Rees R (2014) Understanding the role of the volunteer in specialist palliative care: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Palliat Care 13(1):13–13

Claxton-Oldfield S (2015) Hospice palliative care volunteers: the benefits for patients, family caregivers, and the volunteers. Palliat Support Care 13(3):809–813

Lorhan S, Wright M, Hodgson S, van der Westhuizen M (2014) The development and implementation of a volunteer lay navigation competency framework at an outpatient cancer center. Support Care Cancer 22(9):2571–2580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2238-8

Morris S, Wilmot A, Hill M, Ockenden N, Payne S (2013) A narrative literature review of the contribution of volunteers in end-of-life care services. Palliat Med 27(5):428–436

Burbeck R, Candy B, Low J, Rees R (2014) Understanding the role of the volunteer in specialist palliative care: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Palliative Care 13 (3):doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-1684X-1113-1183

Burbeck R, Low J, Sampson EL, Bravery R, Hill M, Morris S, Ockenden N, Payne S, Candy B (2014) Volunteers in specialist palliative care: a survey of adult services in the United Kingdom. J Palliat Med 17(5):568–574

Nissim R, Regehr M, Rozmovits L, Rodin G (2009) Transforming the experience of cancer care: a qualitative study of a hospital-based volunteer psychosocial support service. Support Care Cancer 17(7):801–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0556-4

Pesut B, Hooper B, Lehbauer S, Dalhuisen M (2014) Promoting volunteer capacity in hospice palliative care: a narrative review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 31(1):69–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909112470485

Wilson DM, Justice C, Thomas R, Sheps S, Macadam M, Brown M (2005) End-of-life care volunteers: a systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Manag Res 18(4):244–257. https://doi.org/10.1258/095148405774518624

Sévigny A, Dumont S, Cohen SR, Frappier A (2010) Helping them live until they die: volunteer practices in palliative home care. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 39(4):734–752. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764009339074

Watts JH (2012) The place of volunteering in palliative care. InTech

Guirguis-Younger M, Grafanaki S (2008) Narrative accounts of volunteers in palliative care settings. Am J Hospice Palliat Med 25(1):16–23

McKee M, Kelley ML, Guirguis-Younger M, MacLean M, Nadin S (2010) It takes a whole community: the contribution of rural hospice volunteers to whole-person palliative care. J Palliat Care 26(2):103–111

Field-Richards SE, Arthur A (2012) Negotiating the boundary between paid and unpaid hospice workers: a qualitative study of how hospice volunteers understand their work. Am J Hospice Palliat Med:1049909111435695

Berry P, Planalp S (2009) Ethical issues for hospice volunteers. Am J Hospice Palliat Med 25(6):458–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909108322291

Jenkinson CE, Dickens AP, Jones K, Thompson-Coon J, Taylor RS, Rogers M, Bambra CL, Lang I, Richards SH (2013) Is volunteering a public health intervention? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the health and survival of volunteers. BMC Public Health 13:773. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-773

Claxton-Oldfield S, Gosselin N, Schmidt-Chamberlain K, Claxton-Oldfield J (2010) A survey of family members’ satisfaction with the services provided by hospice palliative care volunteers. Am J Hospice PalliatMed 27(3):191–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909109350207

Block EM, Casarett DJ, Spence C, Gozalo P, Connor SR, Teno JM (2010) Got volunteers? Association of hospice use of volunteers with bereaved family members’ overall rating of the quality of end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manag 39(3):502–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.310

Luijkx KG, Schols JM (2009) Volunteers in palliative care make a difference. J Palliat Care 25(1):30–39

Gardiner C, Barnes S (2016) The impact of volunteer befriending services for older people at the end of life: mechanisms supporting wellbeing. Progress in Palliative Care 24(3):159–164

Herbst-Damm KL, Kulik JA (2005) Volunteer support, marital status, and the survival times of terminally ill patients. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association 24 (2):225–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.225

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB (2010) Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 7(7):e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Walshe C, Dodd S, Hill M, Ockenden N, Payne S, Preston N, Perez Algorta G (2016) How effective are volunteers at supporting people in their last year of life? A pragmatic randomised wait-list trial in palliative care (ELSA). BMC Med 14(1):203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0746-8

Walshe C, Algorta GP, Dodd S, Hill M, Ockenden N, Payne S, Preston N (2016) Protocol for the End-of-Life Social Action Study (ELSA): a randomised wait-list controlled trial and embedded qualitative case study evaluation assessing the causal impact of social action befriending services on end of life experience. BMC Palliat Care 15(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0134-3

Walshe CD, Payne S, Hill M, Ockenden N, Payne S, Perez Algorta G, Preston N (2016) What is the impact of social action befriending services at the end-of-life? Evaluation of the End of Life Social Action Fund. Lancaster University, Lancaster

McLoughlin K, Rhatigan J, McGilloway S, Kellehear A, Lucey M, Twomey F, Conroy M, Herrera-Molina E, Kumar S, Furlong M, Callinan J, Watson M, Currow D, Bailey C (2015) INSPIRE (INvestigating Social and PractIcal suppoRts at the End of life): pilot randomised trial of a community social and practical support intervention for adults with life-limiting illness. BMC Palliat Care 14(1):65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-015-0060-9

Yin RK (2003) Case study research. Design and method. Applied social research methods series. Volume 5., Third edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Walshe C (2011) The evaluation of complex interventions in palliative care: an exploration of the potential of case study research strategies. Palliat Med 25(8):774–781

Ritchie J, Lewis J (2003) Qualitative research practice. A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage Publications, London

Walshe C, Chew-Graham C, Todd C, Caress A (2008) What influences referrals within community palliative care services? A qualitative case study. Soc Sci Med 67(1):137–146

Robinson J, Gott M, Ingleton C (2014) Patient and family experiences of palliative care in hospital: what do we know? An integrative review. Palliat Med 28(1):18–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313487568

Hill HC, Paley J, Forbat L (2014) Observations of professional–patient relationships: a mixed-methods study exploring whether familiarity is a condition for nurses’ provision of psychosocial support. Palliat Med 28(3):256–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313499960

Sampson C, Finlay I, Byrne A, Snow V, Nelson A (2014) The practice of palliative care from the perspective of patients and carers. BMJ Support Palliat Care 4(3):291–298. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000551

Lewis JM, DiGiacomo M, Currow D, Davidson P (2013) A social capital framework for palliative care: supporting health and well-being for people with life-limiting illness and their carers through social relations and networks. J Pain Symptom Manag 45(1):92–103

Gilbert KL, Quinn SC, Goodman RM, Butler J, Wallace J (2013) A meta-analysis of social capital and health: a case for needed research. J Health Psychol 18(11):1385–1399

Walshe C, Roberts D, Appleton L, Calman L, Large P, Lloyd Williams M, Grande G (2017) Coping well with advanced cancer: a serial qualitative interview study with patients and family Carers. PLoS One 12(1):e0169071

Leonard R, Horsfall D, Noonan K (2015) Identifying changes in the support networks of end-of-life carers using social network analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 5(2):153–159. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000257

Candy B, France R, Low J, Sampson L (2015) Does involving volunteers in the provision of palliative care make a difference to patient and family well-being? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Int J Nurs Stud 52:756–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.08.007

Siette J, Cassidy M, Priebe S (2017) Effectiveness of befriending interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 7(4):e014304. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014304

Kumar S, Calvo R, Avendano M, Sivaramakrishnan K, Berkman LF (2012) Social support, volunteering and health around the world: cross-national evidence from 139 countries. Soc Sci Med 74(5):696–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.017

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D (2015) Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci 10(2):227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Jors K, Tietgen S, Xander C, Momm F, Becker G (2017) Tidying rooms and tending hearts: an explorative, mixed-methods study of hospital cleaning staff's experiences with seriously ill and dying patients. Palliat Med 31(1):63–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216316648071

Falk A, Fischbacher U (2006) A theory of reciprocity. Games Econ Behav 54(2):293–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2005.03.001

Sallnow L, Richardson H, Murray SA, Kellehear A (2016) The impact of a new public health approach to end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 30(3):200–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315599869

Ohlen J, Reimer-Kirkham S, Astle B, Hakanson C, Lee J, Eriksson M, Sawatzky R (2017) Person-centred care dialectics—inquired in the context of palliative care. Nurs Philos 18. https://doi.org/10.1111/nup.12177

Abel J, Walter T, Carey LB, Rosenberg J, Noonan K, Horsfall D, Leonard R, Rumbold B, Morris D (2013) Circles of care: should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support Palliat Care 3(4):383–388

Burt RS (2000) The network structure of social capital. Res Organ Behav 22:345–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(00)22009-1

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of the people who took part in this research, often at a time of great challenge in their lives, thank you. This study would not have been possible without the support of the participating sites, which were responsible for identifying participants, taking consent and managing study participants and site-specific documentation as well as training volunteers and managing the befriending services. With thanks to Dr Evangelia (Evie) Papavasiliou, Research Associate on the project to 15.9.15 who was involved in trial initiation procedures and initial quantitative data collection, and Paul Sharples, Research Intern on the project 11.1.16 – 15.4.16 who assisted with quantitative data entry and initial quantitative data analysis.

Funding

This research was funded by the UK Cabinet Office, who also provided grants to sites to cover the cost of the intervention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CW conceived the study, was the chief investigator and co-wrote the manuscript. CW, NP, SP, GPA and NO co-wrote the protocol and were involved with the conduct of the study. CW, MH and SD were responsible for study data collection and analysis. GPA was the trial statistician. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. CW is the guarantor.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The trial was prospectively registered. Health Research Authority research ethics approval was granted 12.3.15 by NRES Committee Yorkshire & The Humber – South Yorkshire, REC reference 15/YH/0090, IRAS project ID 173058. Site-specific approvals were granted by NRES Committee Yorkshire and the Humber – South Yorkshire.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors, not necessarily those of the Cabinet Office. The funders had no role in collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or in the writing of the report. Reports are seen by them prior to submission, but they have no contribution to the writing or amendment of the report.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dodd, S., Hill, M., Ockenden, N. et al. ‘Being with’ or ‘doing for’? How the role of an end-of-life volunteer befriender can impact patient wellbeing: interviews from a multiple qualitative case study (ELSA). Support Care Cancer 26, 3163–3172 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4169-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4169-2