Abstract

Purpose

Oral nutritional supplements (ONS) are commonly prescribed to malnourished patients to improve their nutritional status. Taste and smell changes in patients with cancer can affect the palatability of ONS. The present study investigated: (1) the palatability of six ONS in testicular cancer patients before, during the first two cycles, and after chemotherapy; (2) the relation between the palatability and taste and smell function; (3) the metallic taste of these ONS.

Methods

Twenty-one testicular cancer patients undergoing first-line cisplatin-based chemotherapy participated. Two milk-based (vanilla; strawberry), two juice-based (apple; orange), and two yoghurt-based (vanilla-lemon; peach-orange) ONS were tested. A questionnaire was used to assess the palatability of ONS and to which extent the attribute ‘metallic’ was applicable. Taste and smell function were measured using taste strips and ‘Sniffin’ Sticks’, respectively.

Results

The palatability of ONS was highly variable among patients. The milk-based strawberry ONS was preferred most before, during, and after chemotherapy. The liking of the milk-based vanilla ONS tended to decrease over time (p = 0.053), whereas the liking of the other ONS remained stable. A higher smell threshold and a lower sour taste threshold were correlated to a decreased liking of the milk-based vanilla ONS. The two juice-based ONS tended to taste more metallic during than before chemotherapy.

Conclusion

Health care professionals and patients should be aware that the palatability of ONS can change over time. Regular structured contact between health care professionals and patients regarding the choice of ONS seems warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Malnutrition is a common problem in cancer patients with a prevalence ranging from 30 to 85 % [1–3]. Oral nutritional supplements (ONS) are commonly prescribed to malnourished patients to improve their nutritional status [4]. ONS can be used in addition to normal food consumption to increase the nutrient intake. A variety of ONS is available, including milk-, juice-, and yoghurt-based ONS in several flavours. The hedonic evaluation of orosensory food cues under standardized conditions, also referred to as palatability [5], plays an important role in the acceptance of ONS [6–8].

Cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy often experience taste and smell changes [9–12]. These chemosensory changes can affect the perceived flavour of ONS. Although frequently prescribed, research regarding the palatability of ONS in patients with cancer is limited. A study in 60 patients with gastrointestinal cancer, of which 47 patients were evaluable at follow-up, found no changes in preference for a fresh milk-based, an ultra-high-temperature (UHT) milk-based, and a fruit-based ONS after 5 weeks of chemotherapy compared to pre-chemotherapy [13]. Another study in 50 patients treated with pelvic radiotherapy (N = 38 at follow-up) found no changes in preference for ONS varying in protein source (elemental, peptide, and polymeric) after 6 weeks of radiotherapy compared to pre-treatment [14]. The relation between taste and smell function and ONS preference was not explored in those studies. Furthermore, the time between the delivery of chemotherapy and study measurements was not specified. This may be important, since differences in taste function, appetite, and food liking can be apparent even within a chemotherapy cycle. A recent study in 52 breast cancer patients treated with anthracycline and/or taxane based chemotherapy showed a decrease in taste function, especially during the first days of a chemotherapy cycle [10]. Changes in taste, appetite, and food liking were cyclic and transient. Therefore, measurements at one time point are unlikely to reflect perception throughout the entire chemotherapy period. This may also be the case for radiotherapy. However, to the best of our knowledge, this has not been investigated systematically in a longitudinal study.

The relation between taste and smell changes in patients with cancer and the palatability of ONS is currently unknown. The relationship between taste function and the palatability of ONS has been addressed by Kennedy et al. (2010) in 48 healthy older adults (63–85 years) compared to younger adults (18–33 years) [15]. In that study [15] the detection and recognition threshold for sweet taste, the perceived intensity of sweetness, overall liking, and ranked preference of three types of ONS were explored. Although older adults had lower sweet thresholds compared to young adults, no difference was found in the perceived intensity of sweetness of the ONS [15]. However, a higher perceived sweetness was associated with overall product dislike for all three ONS across both age groups [15]. Whether a relationship exists between the taste and smell function and the palatability of ONS in cancer patients needs to be explored.

A metallic taste is frequently reported by cancer patients treated with chemotherapy with a prevalence ranging from 10 to 78 % [16]. The mechanism causing metallic taste is still unknown. Metallic taste may be a specific taste alteration like a change in threshold for sweet, sour, salty or bitter taste. Moreover, metallic taste may be a combination of a gustatory and olfactory sensation, implicating ‘metallic flavour’ would be a better term for the experienced sensation. Metallic taste may also be a particular bad taste in the mouth due to the taste of chemotherapeutic agents. Whether certain types of ONS elicit a metallic sensation and may thereby influence the acceptance of ONS in patients with cancer remains to be elucidated.

The present study has the following objectives: (1) to investigate the palatability of six ONS (two milk-based, two juice-based, and two yoghurt-based) in testicular cancer patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy, (2) to explore the relation between ONS palatability and the taste and smell function of these patients, (3) to examine the metallic taste of the ONS. Measurements were performed at five time points: prior to chemotherapy, during the first cycle, before and during the second cycle, and 1 month after start of the last cycle. Since taste and smell function and food liking can vary throughout the chemotherapy treatment, we hypothesised that by measuring the palatability of ONS at multiple time points throughout the chemotherapy treatment, changes in the palatability of ONS can be detected and that changes in taste and smell function can influence the palatability of ONS. Furthermore, we hypothesised that the attribute of metallic taste varies between the ONS types (milk- juice- or yoghurt-based) and can change within a treatment period.

Materials and methods

Study population

Patients with disseminated testicular cancer scheduled to receive first line cisplatin-based chemotherapy consisting of bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) or etoposide and cisplatin (EP) aged 18–50 years were eligible to participate in this study. Patients received three or four cycles of chemotherapy with a cycle interval of 21 days. Inclusion criteria were: age 18–50 years at start of treatment and ability to comprehend Dutch (both reading and writing). Exclusion criteria were: mental disability and co-morbidities affecting taste and/or smell function, such as neurologic disorders, rhinosinusitis, liver or renal problems, hyperactivity or hypoactivity of the thyroid gland or diabetes. Patients had not received other chemotherapy types or concurrent radiotherapy prior to the present study. All patients gave written informed consent. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the University Medical Center Groningen (NCT01641172).

Methods

The present study is part of a larger study regarding taste and smell changes in testicular cancer patients. The taste and smell function and the palatability of ONS were assessed at the following time points: pre-chemotherapy (T0; baseline), during the first cycle (T1; day seven of the first cycle), before the second cycle (T2; day one of the second cycle prior to drug administration), during the second cycle (T3; day seven of the second cycle), and after chemotherapy (T4; 1 month after start of the last cycle). Measurements were performed at the same time of the day for all patients: late morning to early afternoon. The measurements were conducted in the same order for all patients: (1) smell test, (2) taste test, (3) palatability ONS. At baseline, data on height, smoking status, educational level, and sports level were collected during a structured interview. A digital scale was used to measure bodyweight in light clothing, without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m2). Data concerning disease and treatment were derived from medical records.

Oral nutritional supplements

To study the effect of chemotherapy on the pleasantness of ONS regarding type and flavour, a variety of ONS was selected. Six ONS (Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition—Danone) were tested: two high protein milk-based (vanilla and strawberry), two juice-based (apple and orange), and two yoghurt-based (vanilla-lemon and peach-orange) ONS. All ONS had a energy density of 150 kcal/100 ml. The nutrient content varied between the three ONS categories (Online Resource 1).

Procedure

The ONS were served in 30 ml clear plastic tubs at cold temperature. The patients were asked to take at least one sip of each sample. Next, patients had to fill out a questionnaire regarding the palatability and sensory attributes of the ONS on a seven-point scale (Online Resource 2). The questionnaire comprised nine closed questions regarding the palatability, 16 attributes, and two open questions. The following two questions were used from this questionnaire regarding the palatability and metallic taste of ONS: “How much do you like the taste of this product?” (1 = dislike very much, 7 = like very much) and “Please, specify to which extent ‘metallic’ is applicable to the product” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The patients received a warming-up sample (semi-skimmed milk) and completed the questionnaire to get used to the procedure. The ONS were presented in randomized order among patients and test sessions. All samples were labelled with a three-digit-code, varying over test sessions to avoid recognition bias by numbers. Patients were blinded to which ONS was being served. Patients rinsed their mouth with water after each sample.

Taste and smell function

Filter-paper taste strips (Burghart, Wedel, Germany) were used to measure recognition thresholds for sweet, sour, salty, and bitter taste [17]. The patients were requested not to smoke, brush teeth, use chewing gum or to eat or drink with the exception of water 1 h prior to the measurement. The following standard concentrations of each taste were used: sweet: 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 g/ml sucrose; sour: 0.05, 0.09, 0.165, and 0.3 g/ml citric acid; salty: 0.016, 0.04, 0.1, and 0.25 g/ml sodium chloride; bitter: 0.0004, 0.0009, 0.0024, and 0.006 g/ml quinine hydrochloride. The taste strips were placed in the middle of the tongue for whole mouth testing. The taste strips were presented in increasing concentrations in a randomized order. Patients had to choose one of five possible answers (sweet, sour, salty, bitter or no taste). Patients rinsed their mouth with water after each taste strip. Scores for each taste range from 0 (no concentrations correctly identified) to 4 (all concentrations correctly identified). A total taste score (range 0–16) was derived by summing the scores for all tastes.

‘Sniffin’ Sticks’ (Burghart, Wedel, Germany) were used to measure the smell function [18, 19]. In brief, this test consists of pen-like odour dispensing devices and includes three parts: a threshold (THR) test, a discrimination (DIS) test, and an identification (ID) test. The pens were presented approximately 2 cm under the middle of the nose. To measure the THR, a standard series of pens with 16 dilutions of n-butanol was used. Three pens were presented in a randomized order, one contained the odorant and two solvent. The patients had to identify the pen containing the odorant in two successive trials, which triggered a reversal of the staircase. The THR was defined as the mean of the last four reversals. For the DIS test, 16 triplets (two equal and one different odorant) were presented. The patients had to discriminate which of the three pens smelled differently. For the ID test, 16 common odours were presented and the patients had to identify the odour using a multiple choice task presented on a list of four different odorants. For the THR and DIS test, there was a 30-s interval between the presentation of the first pen of a triplet and the presentation of the first pen of the following triplet. The pens for the ID test and the taste strips were presented at a 30-s interval. The patients were requested not to smoke, brush teeth, use chewing gum or to eat or drink with the exception of water 15 min prior to the measurement. The THR score ranges from 1 to 16. The DIS and ID scores range from 0 to 16. A total smell score was derived by summing the THR, DIS and ID, resulting in a threshold, discrimination, identification (TDI) score (range 1–48). The extended version of the ‘Sniffin’ Sticks’ was used, containing 32 odour combinations for the DIS test and 32 odours for the ID test [20]. Each patient received a unique combination of 16 out of 32 triplets for the DIS test, and a unique combination of 16 out of 32 pens for the ID test.

Metallic taste

Two aspects of metallic taste were addressed. Patients had to report to which extent metallic was applicable to the ONS. Furthermore, patients had to report whether they experienced a metallic taste as a side effect of chemotherapy. To examine this second aspect, patients were asked to respond to the following open-ended questions regarding their subjective taste perception since the start of treatment: “Have you experienced a change in taste?” and “Have you experienced certain foods to taste differently?”. In addition, patients had to report how often they experienced a continuous bad taste in their mouth (never, rarely, sometimes, often or always) and patients had to describe the experienced taste with the following response options “sweet, sour, salty, bitter or other namely”. Patients were classified as experiencing a metallic taste, when they reported a metallic taste as a change in taste or as a bad taste in the mouth. By exploring both aspects of metallic taste, investigation whether especially the patients who experienced a metallic taste as a side effect of chemotherapy reported that metallic taste was applicable to ONS could be performed. Moreover, this enables investigation whether a metallic taste is applicable for specific types of ONS in cancer patients.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as median with interquartile range (IQR) or percentage. Possible differences in palatability and metallic taste between the ONS per test session were investigated using the Friedman test, followed by the post-hoc related-samples Wilcoxon signed-rank test. A linear mixed model was used to investigate taste and smell function and the liking and metallic taste of each ONS separately, over time. An unstructured covariance type was used to model the covariance structure among repeated measures. For ONS showing a significant change or a trend towards significance in liking or metallic taste over time, possible differences in liking and metallic taste were compared to baseline and possible differences during the second cycle were explored. Test session was entered as fixed effect in the model (T0 as baseline). Contrast comparisons were carried out to explore possible differences during the second cycle (T2 versus T3). All models were estimated using maximum likelihood. Spearman’s rho correlation (r s) was used to investigate the relation between taste and smell function and the liking of each ONS over all test sessions. For ONS showing a significant change in liking compared to baseline, spearman’s rho correlation was used to explore the relation between changes in taste and smell function and the change in liking compared to baseline. For taste and smell parameters without a change over time (i.e. all parameters, except salty taste), the mean of the taste and smell parameters over all test sessions was used for correlations (instead of the change over time of these parameters). Spearman’s rho correlation was used to explore the correlation between overall liking and metallic taste of ONS over all test sessions, across all ONS and per ONS separately. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the scores to which extent ‘metallic’ was applicable for each ONS with respect to presence of metallic taste in patients. For this end, the highest rating reported by each patient during test sessions in which patients reported a metallic taste (T3 and T4) was used. Patients with missing data on a variable relevant for a specific analysis were excluded (indicated in tables). Given the exploratory nature of the study, no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. A two-tailed p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 22 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL).

Results

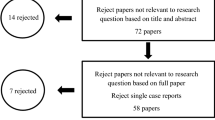

Characteristics of the study population

Twenty-eight patients were asked to participate. Twenty-one patients were enrolled in the study. Reasons for not participating were: study too time consuming (n = 2) or unknown reasons (n = 5). The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Four patients stopped their participation prematurely (after T0: N = 2, after T1: N = 1, after T3: N = 1). Three patients completed four out of five measurements due to illness during chemotherapy (T1: N = 1, T3: N = 2).

Palatability of ONS

Table 2 shows the liking scores of each ONS per test session. The liking of the milk-based vanilla ONS tended to decrease over time (p = 0.053), whereas the liking of the other ONS remained stable. The liking of the milk-based vanilla ONS decreased before and during the second cycle and after chemotherapy compared to baseline (T2: p = 0.025; T3: p = 0.008; T4: p = 0.030). See Online Resource 3 for estimates of fixed effects. No difference in liking of the milk-based strawberry ONS was found compared to baseline. Figure 1 shows the liking scores of the milk-based vanilla and strawberry over time. A wide variation in ONS liking was found among patients (see Online Resource 4 for difference in liking compared to baseline). A difference in liking between the ONS was found prior to chemotherapy (T0, p = 0.019), during the first cycle (T1, p = 0.001), and after chemotherapy (T4, p < 0.001). Patients preferred the milk-based strawberry ONS during all test sessions. The liking of this ONS was significantly higher than the juice-based orange (p = 0.010) and the yoghurt-based vanilla-lemon (p = 0.021) ONS prior to chemotherapy (T0) and higher than all other ONS during the first cycle (T1) and after chemotherapy (T4) (p < 0.05). See Online Resource 5 for the ranked preference based on liking scores of the ONS per test session.

Taste and smell function and the palatability of ONS

The threshold for salty taste increased after chemotherapy (T4) compared to baseline (median (IQR); T0: 3 (3–3) and T4: 2 (2–3); p = 0.006). No changes in the other primary tastes or in smell function were found in patients compared to baseline (data not shown).

A higher threshold for sweet and sour taste was correlated with a higher liking of the milk-based strawberry ONS (sweet: r s = −0.23, p = 0.026; sour: r s = −0.32, p = 0.002). A higher threshold for sour taste was correlated with a higher liking of the juice-based orange ONS (r s = −0.21, p = 0.044). A lower threshold for sweet and bitter taste was correlated with a higher liking of the yoghurt-based peach-orange ONS (sweet: r s = 0.22, p = 0.040; bitter: r s = 0.29, p = 0.006). No significant correlations were found between the salty taste threshold and the liking of ONS.

A lower threshold for sour taste was correlated with a decreased liking of this ONS before the second cycle (T2) and after chemotherapy (T4) compared to baseline (T2–T0: r s = −0.57, p = 0.026; T4–T0: r s = −0.53, p = 0.043). No significant correlations were found between the liking of ONS and the smell DIS and ID.

A higher smell threshold was correlated to a lower liking of the milk-based vanilla ONS over all time points (r s = 0.23, p = 0.030), the juice-based orange ONS (r s = 0.21, p = 0.043), and the yoghurt-based vanilla-lemon and peach-orange ONS (r s = 0.24, p = 0.021 and r s = 0.25, p = 0.017, respectively).

A higher smell threshold was correlated with a decrease in liking of the milk-based vanilla during the first cycle (T1) compared to baseline (r s = 0.65, p = 0.006).

Metallic taste and the palatability of ONS

Table 3 shows the scores to which extent ‘metallic’ was applicable for each ONS per test session. No difference was found regarding this attribute between the ONS per test session. Overall, metallic taste of ONS was associated with a lower liking of ONS (r s = −0.34, p < 0.001). Metallic taste was also associated with a lower liking per ONS separately: milk-based vanilla: r s = −0.29, p = 0.005); milk-based strawberry: r s = −0.26, p = 0.013; juice-based apple: r s = −0.36, p < 0.001; juice-based orange: r s = −0.53, p < 0.001; yoghurt-based vanilla-lemon: r s = −0.26, p = 0.013; yoghurt-based peach-orange: r s = −0.20, p = 0.064).

The metallic taste of the juice-based apple ONS increased over time (p = 0.037) (Table 3). The metallic taste of this ONS increased during the first cycle (T1) and after chemotherapy (T4) compared to baseline (p = 0.019 and p = 0.006, respectively). An increased trend for metallic taste of the juice-based orange ONS was found (p = 0.056). The metallic taste of this ONS increased before the second cycle (T2) and after chemotherapy (T4) compared to baseline (p = 0.005 and p = 0.045, respectively). See Online Resource 3 for estimates of fixed effects.

Five of 21 patients (24%) reported a metallic taste. Three of these patients experienced a metallic taste during the second cycle (T3) and two patients reported metallic taste after chemotherapy (T4). The score to which extent ‘metallic’ was applicable for each ONS was higher for patients experiencing a metallic taste compared to patients who did not experience a metallic taste (median score of 6 versus 5, p = 0.035).

Discussion

The present study examined for the first time the palatability of several ONS types and flavours at multiple time points during treatment. In line with previous studies which measured the palatability only at one time point during treatment [13, 14], no effect of treatment was found for the palatability of five out of six ONS, suggesting that preference for most types and flavours of ONS remain stable over time.

The palatability of the milk-based vanilla ONS tended to decrease over time, whereas the high liking of the milk-based strawberry ONS remained stable. The flavour, rather than the nutrient content, played a role in the decreased preference of the milk-based vanilla ONS, since the macro- and micronutrient content of these two ONS were identical. Moreover, the taste and smell function of patients with cancer may have played a role, since a higher smell threshold and a lower sour taste threshold were associated with a decreased liking of the milk-based vanilla ONS.

Patients preferred the milk-based strawberry ONS before, during, and after chemotherapy over the other five ONS. Other studies have also shown a preference for milk-based over juice-based ONS in patients with cancer [13] and in a heterogeneous group of malnourished patients [21]. Nevertheless, a wide variation in pleasantness was found among patients. Therefore, a variety of ONS types and flavours should be offered to patients, so they can choose the product they like most. The pleasantness of the milk-based vanilla ONS tended to decrease over time. As a consequence, health care professionals should inform patients that the palatability of ONS can change over time and regular structured contact between health care professionals and patients regarding the choice of ONS is warranted.

The metallic taste of both juice-based ONS tended to increase during chemotherapy. These results suggest that juice-based ONS are the least suitable ONS for patients experiencing a metallic taste, which has a high prevalence in cancer patients treated with chemotherapy [16]. Patients were not specifically asked whether they experienced a metallic taste during the present study. Nevertheless, approximately 25% of the patients reported metallic taste using a questionnaire including a question regarding the description of the experienced taste alteration (sweet, sour, salty, bitter or “other namely”). The patients reported ‘metallic’ using this alternative response option. Future studies with larger sample size including the investigation of the mechanism of metallic taste are needed to explore the relation between metallic taste experienced by patients with cancer and the metallic taste of ONS in more detail. More detailed information may improve the palatability of ONS for patients who experience a metallic taste.

Strengths of the present study are the longitudinal design including multiple time points during chemotherapy and the homogeneous study population regarding type of cancer and treatment, and treatment phase. A limitation is that no conclusion can be drawn regarding the compliance to ONS, since only the palatability of the ONS was assessed. Furthermore, the threshold of umami taste was not investigated. The umami taste may be relevant, since this is linked to the enjoyment of protein rich food. However, the umami taste may not always be recognized by the western population and including the measurement of the umami threshold together with the other primary tastes may be confusing for participants [22]. Finally, although sweet milk-based ONS and more sour-like juice- and yoghurt-based ONS were used in the present study, the patients were not asked regarding the perceived intensity of sweetness, sourness, saltiness, and bitterness of the ONS. Information concerning the basic orientation of the ONS may relate to the taste function of the patients and the palatability of ONS.

To conclude, a variety of types of ONS and flavours should be offered to malnourished patients with cancer throughout the whole treatment period, since preference is variable among patients and the palatability of certain ONS can change over time. Furthermore, the taste and smell function can influence the palatability of ONS. Health care professionals should inform patients that the palatability of ONS can change over time and regular structured contact between health care professionals and patients regarding the choice of ONS is warranted.

References

Pressoir M, Desné S, Berchery D, Rossignol G, Poiree B, Meslier M, Traversier S, Vittot M, Simon M, Gekiere JP, Meuric J, Serot F, Falewee MN, Rodrigues I, Senesse P, Vasson MP, Chelle F, Maget B, Antoun S, Bachmann P (2010) Prevalence, risk factors and clinical implications of malnutrition in French comprehensive cancer Centres. Br J Cancer 102:966–971

Segura A, Pardo J, Jara C, Zugazabeitia L, Carulla J, de Las Peñas R, García-Cabrera E, Luz Azuara M, Casadó J, Gómez-Candela C (2005) An epidemiological evaluation of the prevalence of malnutrition in Spanish patients with locally advanced or metastatic cancer. Clin Nutr 24:801–814

Wie G, Cho Y, Kim S, Kim S, Bae J, Joung H (2010) Prevalence and risk factors of malnutrition among cancer patients according to tumor location and stage in the National Cancer Center in Korea. Nutrition 26:263–268

Stratton RJ, Elia M (2007) A review of reviews: a new look at the evidence for oral nutritional supplements in clinical practice. Clin Nutr Suppl 2:5–23

Yeomans MR (1998) Taste, palatability and the control of appetite. Proc Nutr Soc 57:609–615

Ravasco P (2005) Aspects of taste and compliance in patients with cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 9(Suppl 2):S84–S91

Gosney M (2003) Are we wasting our money on food supplements in elder care wards? J Adv Nurs 43:275–280

Ozçagli TG, Stelling J, Stanford J (2013) A study in four European countries to examine the importance of sensory attributes of oral nutritional supplements on preference and likelihood of compliance. Turk J Gastroenterol 24:266–272

Coa KI, Epstein JB, Ettinger D, Jatoi A, McManus K, Platek ME, Price W, Stewart M, Teknos TN, Moskowitz B (2015) The impact of cancer treatment on the diets and food preferences of patients receiving outpatient treatment. Nutr Cancer 67(2):339–353

Boltong A, Aranda S, Keast R, Wynne R, Francis PA, Chirgwin J, Gough K (2014) A prospective cohort study of the effects of adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy on taste function, food liking, appetite and associated nutritional outcomes. PLoS One 9:e103512–e103512

Steinbach S, Hummel T, Böhner C, Berktold S, Hundt W, Kriner M, Heinrich P, Sommer H, Hanusch C, Prechtl A, Schmidt B, Bauerfeind I, Seck K, Jacobs VR, Schmalfeldt B, Harbeck N (2009) Qualitative and quantitative assessment of taste and smell changes in patients undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer or gynecologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol 27:1899–1905

Gamper E, Giesinger JM, Oberguggenberger A, Kemmler G, Wintner LM, Gattringer K, Sperner-Unterweger B, Holzner B, Zabernigg A (2012) Taste alterations in breast and gynaecological cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: prevalence, course of severity, and quality of life correlates. Acta Oncol 51:490–496

Rahemtulla Z, Baldwin C, Spiro A, McGough C, Norman AR, Frost G, Cunningham D, Andreyev HJ (2005) The palatability of milk-based and non-milk-based nutritional supplements in gastrointestinal cancer and the effect of chemotherapy. Clin Nutr 24:1029–1037

McGough C, Peacock N, Hackett C, Baldwin C, Norman A, Frost G, Blake P, Tait D, Khoo V, Harrington K, Whelan K, Andreyev HJ (2006) Taste preferences for oral nutrition supplements in patients before and after pelvic radiotherapy: a double-blind controlled study. Clin Nutr 25:906–912

Kennedy O, Law C, Methven L, Mottram D, Gosney M (2010) Investigating age-related changes in taste and affects on sensory perceptions of oral nutritional supplements. Age Ageing 39:733–738

IJpma I, Renken RJ, Ter Horst GJ, Reyners AKL (2015) Metallic taste in cancer patients treated with chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev 41:179–186

Mueller C, Kallert S, Renner B, Stiassny K, Temmel AFP, Hummel T, Kobal G (2003) Quantitative assessment of gustatory function in a clinical context using impregnated “taste strips”. Rhinology 41:2–6

Hummel T, Sekinger B, Wolf SR, Pauli E, Kobal G (1997) ‘Sniffin’ Sticks’: olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem Senses 22:39–52

Wolfensberger M, Schnieper I, Welge-Lüssen A (2000) Sniffin’ Sticks: a new olfactory test battery. Acta Otolaryngol 120:303–306

Haehner A, Mayer A, Landis BN, Pournaras I, Lill K, Gudziol V, Hummel T (2009) High test-retest reliability of the extended version of the “Sniffin’ Sticks” test. Chem Senses 34:705–711

Darmon P, Karsegard VL, Nardo P, Dupertuis YM, Pichard C (2008) Oral nutritional supplements and taste preferences: 545 days of clinical testing in malnourished in-patients. Clin Nutr 27:660–665

Bellisle F (2008) Experimental studies of food choices and palatability responses in European subjects exposed to the umami taste. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 17(Suppl 1):376–379

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by TI Food and Nutrition. All authors drafted, read, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The ONS used in the present study were supplied by Danone.

Role of funding sources

The project is funded by TI Food and Nutrition, a public-private partnership on precompetitive research in food and nutrition. The public partner (University Medical Center Groningen) is responsible for the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript. The private partners (Danone and FrieslandCampina) have contributed to the project through regular discussion.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

IJpma, I., Renken, R.J., Ter Horst, G.J. et al. The palatability of oral nutritional supplements: before, during, and after chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 24, 4301–4308 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3263-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3263-6