Abstract

Purpose

Contrary to the approved indication for pegfilgrastim prophylaxis, some patients receive it on the same day as the last administration of chemotherapy in clinical practice, which could adversely impact risk of febrile neutropenia (FN). An evaluation of the timing of pegfilgrastim prophylaxis and FN risk was undertaken.

Methods

A retrospective cohort design and data from two US private health care claims repositories were employed. Study population comprised adults who received intermediate/high-risk chemotherapy regimens for solid tumors or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and received pegfilgrastim prophylaxis in ≥1 cycle; all cycles with pegfilgrastim were pooled for analyses. Odds ratios (OR) for FN during the cycle were estimated for patients who received pegfilgrastim on the same day (day 1) as the last administration of chemotherapy versus days 2–4 from chemotherapy completion.

Results

The study population included 45,592 patients who received pegfilgrastim in 179,152 cycles (n = 37,095 in cycle 1); in 12 % of cycles, patients received pegfilgrastim on the same day as chemotherapy. Odds of FN were higher for patients receiving pegfilgrastim prophylaxis on the same day as chemotherapy versus days 2–4 from chemotherapy in cycle 1 (OR = 1.6, 95 % CI = 1.3–1.9, p < 0.001) and all cycles (OR = 1.5, 95 % CI = 1.3–1.6, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

In this large-scale evaluation of adults who received intermediate/high-risk regimens for solid tumors or NHL in US clinical practice, FN incidence was found to be significantly higher among those who received pegfilgrastim prophylaxis on the same day as chemotherapy completion versus days 2–4 from chemotherapy completion, underscoring the importance of adhering to the indicated administration schedule.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neutropenia is a common side effect of myelosuppressive chemotherapy that increases the risk of infection. When neutropenic patients develop fever (i.e., febrile neutropenia (FN)), the high likelihood of infection and serious consequences often necessitate hospitalization for urgent evaluation, ongoing monitoring, and administration of intravenous (IV) antibiotics [1, 2]. FN, as well as severe or prolonged neutropenia, can lead to chemotherapy dose-delays, dose-reductions, and/or discontinuation, interfering with the delivery of optimal cancer treatment and possibly adversely affecting patient outcomes [1, 3–7].

For adult patients receiving chemotherapy for solid tumors or non-myeloid malignancies, clinical practice guidelines recommend prophylaxis with a colony-stimulating factor (CSF) when FN risk is high (>20 %) based on either chemotherapy regimen risk alone or a combination of regimen risk and patient risk factors [1, 8]. Among the CSFs that are commercially available in the USA, pegfilgrastim is the agent most widely used in clinical practice as, unlike the other agents that are administered daily, it requires only a single dose in each chemotherapy cycle [9–12]. Because pegfilgrastim rapidly induces the proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells—which may be especially sensitive to myelotoxic agents and could adversely impact the risk of FN—prescribing information specifies that pegfilgrastim should not be administered between 14 days before and 24 h after administration of myelosuppressive chemotherapy. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines on myeloid growth factor use state that “the majority of trials administered pegfilgrastim the day after chemotherapy” (based on category 1 evidence: high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate) and “administration of pegfilgrastim up to 3–4 days after chemotherapy is also reasonable based on trials with filgrastim” [8, 12–18]. Similarly, the recently promulgated American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines indicate that pegfilgrastim should be administered on days 2–4 from chemotherapy completion, if possible [1].

Accumulating—albeit limited—evidence from clinical practice suggests that many patients receive pegfilgrastim on the same day as the last administration of chemotherapy, rather than during days 2–4 from chemotherapy completion, which often requires an extra clinic visit [19–22]. Several studies have evaluated the efficacy/effectiveness of pegfilgrastim prophylaxis administered on the same day as chemotherapy versus the day(s) after chemotherapy, but these studies have been small, have sometimes been inconclusive, and have—taken collectively—produced mixed results [20, 23–31]. Moreover, the NCCN guidelines state that “limited data suggest that same-day administration of pegfilgrastim may be considered in certain circumstances,” and that such use of pegfilgrastim is done for “logistical reasons and to minimize burdens on long-distance patients” [8]. In addition, the ASCO guidelines indicate that because some patients may not be able to return on days 2–4 from chemotherapy completion due to—for example—distance or mobility, it is better to administer same-day pegfilgrastim than no pegfilgrastim [1]. Accordingly, a retrospective evaluation was undertaken to provide real-world evidence on the use and potential implications of the timing of pegfilgrastim prophylaxis among adults who received intermediate/high-risk chemotherapy regimens for solid tumors or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) in US clinical practice.

Methods

Study design and data source

This study employed a retrospective cohort design and data from two large health care claims repositories spanning the period from January 1, 2003, through December 31, 2011. Patient-level claims data from the two repositories were pooled for analyses. The two study repositories―Truven Health Analytics MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters and Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits Databases (MarketScan Database) and IMS LifeLink™ PharMetrics Plus Health Plan Claims Database (LifeLink Database)―comprise medical (i.e., facility and professional service) and outpatient pharmacy claims from a large number of participating private US health plans.

The study databases were de-identified prior to their release to study investigators, and thus, their use for health services research is fully compliant with the HIPAA Privacy Rule and federal guidance on Public Welfare and the Protection of Human Subjects [32]. A detailed description of study design and study methods may be found in the online supplement (Online Resource A).

Source and study populations

The source population comprised all patients aged ≥18 years who, between July 1, 2003, and June 30, 2011, received ≥1 course of myelosuppressive chemotherapy for a single primary solid tumor or NHL. Patients who did not have medical and drug benefits for ≥6 months prior to their qualifying chemotherapy course or who did not meet other inclusion criteria (as described in the online supplement) were excluded from the source population. For each patient in the source population, the first unique observed course of chemotherapy, and each cycle within the first course, was identified. From the source population, all patients who received intermediate/high-risk chemotherapy regimens and pegfilgrastim prophylaxis in ≥1 cycle of chemotherapy were selected for inclusion in the study population. To ensure adequate sample size for cancer/regimen-specific analyses, the study population was further limited on an a priori basis to patients who received chemotherapy regimens that are commonly used in US clinical practice [11, 33, 34].

Pegfilgrastim prophylaxis was ascertained based on corresponding Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) level II codes (C9119, S0135, J2505) on medical claims with service dates on or up to 3 days after the last day of chemotherapy administration in a given cycle. Patient-cycles with pegfilgrastim prophylaxis were categorized into subgroups based on whether pegfilgrastim was administered on the same day as the last administration of chemotherapy (same day [day 1] as chemotherapy) versus during days 2–4 from completion of chemotherapy (days 2–4 from chemotherapy) and were pooled for analyses. (Because all chemotherapy regimens considered in this study are fully administered on the first day of the cycle, “same day as chemotherapy” refers to cycle day 1.) To minimize confounding, patient-cycles were excluded if there was evidence of prophylaxis with other CSF or antibiotic agents or if there was evidence of FN prior to administration of pegfilgrastim during the cycle.

FN episodes

FN episodes were ascertained during the period beginning on day 5 from chemotherapy completion through the last day of that cycle and were identified using a “broad” definition as follows [35]: FN episodes requiring inpatient care were identified based on hospital admissions with a principal or secondary diagnosis of neutropenia (ICD-9-CM 288.0), or fever (780.6), or infection. FN episodes requiring outpatient care only were identified based on ambulatory encounters (e.g., those in a physician’s office, emergency department, or home) with a diagnosis of neutropenia, or fever, or infection and—on the same date—a HCPCS level I (i.e., CPT) code for IV administration of antimicrobial therapy. Such encounters that preceded or followed an FN-related hospitalization during the same cycle of chemotherapy were not considered as a separate outpatient episode (i.e., they were classified as part of the episode of FN requiring inpatient care). An alternative (narrow) definition for FN comprising inpatient encounters with a principal or secondary diagnosis of neutropenia, and outpatient encounters with a diagnosis of neutropenia and evidence of IV antimicrobial therapy, was also evaluated [35].

Patient, cancer, and treatment characteristics

Characteristics included age; sex; presence of selected chronic comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, liver disease, lung disease, renal disease, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid disease, thyroid disorder); body weight/nutritional status (obesity, underweight, malnutrition); proxies for health status (hospice/skilled nursing facility (SNF) care) and physical function (use of hospital bed, supplemental oxygen, walking aid, wheelchair); use of immunosuppressive therapy; history of blood disorders (anemia, neutropenia, other), infection, recent surgery, hospitalization (all-cause), chemotherapy, and radiation therapy; total health care expenditures during the baseline period; and calendar year of chemotherapy initiation. All characteristics (except for recent surgery) were assessed during the 12-month pre-chemotherapy period; recent surgery was assessed during the 90-day pre-chemotherapy period.

Statistical analyses

Odds ratios for FN—unadjusted and adjusted for characteristics of patients, their cancer, and their chemotherapy regimen—among patients who received pegfilgrastim prophylaxis on the same day as chemotherapy versus days 2–4 from chemotherapy were estimated using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with a binomial distribution, logistic link function, and exchangeable correlation structure. The GEE method accounts for correlation among repeated measures for the same subject (in this instance, among cycles), while controlling for both variables that are invariant as well as those that may vary across observations. Adjusted analyses were conducted using backward selection of the aforementioned patient, cancer, and treatment characteristics.

Analyses were conducted considering all study subjects, the first cycle, and all FN episodes (i.e., irrespective of care setting), as well as considering all cycles, inpatient FN episodes only, and the narrow definition for FN, respectively. Analyses also were conducted within subgroups of the study population defined on the basis of cancer type and chemotherapy regimen.

All statistical tests were two-sided and were performed at a significance level of α = 0.05; adjustments for multiple comparisons were not employed. Assuming that pegfilgrastim would be administered on the same day as chemotherapy in 13 % of cycles, and that FN risk would be higher in these cycles by 50 % (4.5 vs. 3 %), the minimum total sample size—corresponding to 80 % power, with two-sided α = 0.05—was calculated to be approximately 11,000 patients [24, 26, 33].

Results

A total of 491,990 adult patients underwent a course of myelosuppressive chemotherapy for a single primary solid tumor or NHL from July 2003 through June 2011 and met all other patient-level criteria for inclusion in the source population (Online Resource B). Among these patients, 45,592 received one of the selected intermediate/high-risk chemotherapy regimens, received pegfilgrastim prophylaxis in ≥1 cycle, and met all cycle-level criteria for inclusion in the study population. Study subjects received pegfilgrastim prophylaxis in a total of 179,152 cycles (n = 37,095 in cycle 1); in 12 % of cycles, patients received pegfilgrastim on the same day as chemotherapy administration (and thus in a manner inconsistent with the indicated schedule).

Among study subjects who received pegfilgrastim prophylaxis in cycle 1, 78 % had non-metastatic breast cancer (54 % of these patients received doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide with or without subsequent docetaxel or paclitaxel [AC-T/AC, dose-dense]), 14 % had NHL (cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + vincristine + prednisone with or without rituximab [R-CHOP/CHOP]), 5 % had non-metastatic lung cancer (carboplatin + paclitaxel [CAR + PAC]), and 3 % had non-metastatic ovarian cancer (CAR + PAC). Baseline characteristics of patients receiving pegfilgrastim prophylaxis on the same day as chemotherapy versus days 2–4 from chemotherapy were generally comparable; although some characteristics were statistically different between subgroups, such variation in values was not clinically meaningful (e.g., mean age, 54.5 vs. 55.5 years, p < 0.001) (Table 1).

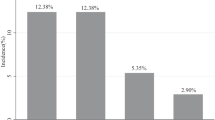

On an overall basis, the incidence proportion for FN (all episodes) during first cycles among patients receiving pegfilgrastim prophylaxis on the same day as chemotherapy was 3.9 %, versus 2.8 % among those receiving prophylaxis on days 2–4 from chemotherapy; the corresponding adjusted odds ratio was 1.6 (95 % CI = 1.3–1.9, p value <0.001) (Fig. 1). The incidence proportion for FN (all episodes) during all cycles with pegfilgrastim prophylaxis was 2.5 % (same day as chemotherapy) versus 1.9 % (days 2–4 from chemotherapy), and the corresponding adjusted odds ratio was 1.5 (95 % CI = 1.3–1.6, p value <0.001). Adjusted odds ratios when considering all cycles and only inpatient FN episodes (OR = 1.5, 95 % CI = 1.3–1.6, p value <0.001)—which accounted for 86 % of all episodes—and the narrow definition for FN (OR = 2.0, 95 % CI = 1.8–2.3, p value <0.001) were comparable. Tables describing the selection of source/study populations, baseline characteristics of patients within cancer/regimen-specific subgroups, and odds ratios for FN within cancer/regimen-specific subgroups are set forth in the online supplement (Online Resource B).

Discussion

Prescribing information specifies that pegfilgrastim should not be administered between 14 days before and 24 h after administration of myelosuppressive chemotherapy, and the majority of data from clinical trials provide evidence on the efficacy of pegfilgrastim and thus support its use according to this schedule [9, 14–16]. The results of our study suggest, however, that an important minority (12 %) of cancer patients receiving pegfilgrastim prophylaxis during intermediate/high-risk chemotherapy regimens for solid tumors and NHL in US clinical practice receives pegfilgrastim in a manner inconsistent with prescribing information (i.e., on the same day as chemotherapy administration).

More notably, the results of this study also suggest that the odds of FN are substantially higher (by 1.5–2.0 times) among patients who receive pegfilgrastim on the same day as chemotherapy versus those who receive pegfilgrastim on days 2–4 from chemotherapy. These results were found to be robust when considering the first cycle only, all cycles, only inpatient FN episodes, and a narrow definition for FN. While the precise reasons for the timing of pegfilgrastim administration in our study are unknown, the use of prophylaxis on the same day as chemotherapy should be carefully considered by providers as the results of this study suggest that such use may lead to additional FN events, most of which require hospitalization and are associated with severe consequences [2, 4, 19, 36, 37].

While recognizing the inherent limitations of retrospective evaluations using health care claims databases, we note that the findings described herein are based on analyses of over 37,000 patients (and nearly 180,000 chemotherapy cycles) with a broad spectrum of cancer/regimen combinations, which is substantially larger than the collective populations in all of the aforementioned published studies. In the four studies that support use of pegfilgrastim prophylaxis according to the indicated schedule—including two retrospective evaluations and two randomized trials—sample sizes ranged from 75 to 214, while in the three studies that provide evidence in support of same-day prophylaxis—including two retrospective evaluations and one randomized trial—sample sizes ranged from 46 to 230 [20, 24–27]. Evidence from randomized trials was reported by Burris and colleagues, who conducted four individual phase II randomized, double-blind studies of patients with breast cancer (n = 90), NHL (n = 75), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (n = 88), and ovarian cancer (n = 19), respectively, across 74 clinical sites [24]. In the breast cancer and NHL trials, the incidence of severe neutropenia in cycle 1 was found to be higher, and the duration of severe neutropenia longer, among patients who received pegfilgrastim on the same day as chemotherapy versus those who received it on the day after chemotherapy. In the NSCLC trial, however, the incidence and duration of severe neutropenia in cycle 1 were found to be comparable between the same-day and next-day prophylaxis groups. Comparisons of patients with ovarian cancer were limited due to premature discontinuation of the trial.

We mention a few important limitations and possibilities for bias in the current study. In clinical practice, patients who received pegfilgrastim prophylaxis on the same day as chemotherapy may be systematically different than those who received prophylaxis on days 2–4 from chemotherapy, and to the extent such differences are unobserved, study results may be biased. Because there is no ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for FN, codes for neutropenia, fever, and infection were employed to identify inpatient and outpatient encounters that are assumed to be related to FN. Since patients are typically not given chemotherapy when they are neutropenic or have active infection, the appearance of codes for neutropenia, fever, or infection within a defined exposure period after receiving chemotherapy increases the likelihood that such outcomes are related to receipt of chemotherapy. While the sensitivity of the broad definition for FN used in this study is likely higher than that of the narrow definition using only the ICD-9-CM code for neutropenia, the specificity and positive predictive value are likely lower, chiefly due to the inclusion of infections occurring in the absence of fever and neutropenia [35]. The likelihood of FN occurring after cycle day 14 is low, and some infection-related encounters may occur after chemotherapy-induced neutropenia has resolved [38]. While the precise direction and magnitude of this bias is unknown, there is no reason to believe that the bias should disproportionately impact patients receiving prophylaxis on the same day as chemotherapy versus days 2–4 from chemotherapy.

Because the accuracy of algorithms/variables capturing the presence of acute and chronic conditions is undoubtedly less than perfect, and because histories are left-truncated, some patients may be misclassified in terms of their comorbidity profile and/or pre-chemotherapy health care experience. Similarly, the accuracy of our algorithms for identifying the primary cancer type and presence of metastatic disease is unknown. Finally, because the study population principally comprised cancer patients aged less than 65 years with coverage from private US health plans, the study population may not reflect US patients treated in clinical practice across the USA. Consequently, study results may not be generalizable to those with public health insurance, the uninsured, and older patients.

In summary, in this retrospective evaluation of cancer patients receiving pegfilgrastim during intermediate/high-risk regimens for solid tumors and NHL in US clinical practice, one in every eight patients received prophylaxis on the same day as chemotherapy administration. FN risk among these subsets was substantially higher than it was among those who received it on days 2–4 from chemotherapy. The results of this study underscore the importance of adhering to the indicated administration schedule for pegfilgrastim.

References

Smith TJ, Bohlke K, Lyman GH et al (2015) Recommendations for the use of WBC growth factors: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3488

Caggiano V, Weiss RV, Rickert TS et al (2005) Incidence, cost and mortality of neutropenia hospitalization associated with chemotherapy. Cancer 103:1916–1924

Lyman GH, Michels SL, Reynolds MW et al (2010) Risk of mortality in patients with cancer who experience febrile neutropenia. Cancer 116:5555–5563

Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J et al (2006) Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia in adult cancer patients. Cancer 106:2258–2266

Bonadonna G, Moliterni A, Zambetti M et al (2005) 30 years’ follow up of randomised studies of adjuvant CMF in operable breast cancer: cohort study. BMJ 330(7485):217

Lyman GH, Dale DC, Crawford J (2003) Incidence and predictors of low dose-intensity in adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy: a nationwide study of community practices. J Clin Oncol 21:4524–4531

Kwak LW, Halpern J, Olshen RA et al (1990) Prognostic significance of actual dose intensity in diffuse large-cell lymphoma: results of a tree-structured survival analysis. J Clin Oncol 8(6):963–977

NCCN (2014) The NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myeloid growth factors [v1.2014]. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#myeloid_growth. Accessed August 8, 2014

Amgen Inc. (2009) Neulasta (pegfilgrastim) prescribing information, Thousand Oaks, CA

Heaney ML, Toy EL, Vekeman F et al (2009) Comparison of hospitalization risk and associated costs among patients receiving sargramostim, filgrastim, and pegfilgrastim for chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Cancer 115:4839–4848

Weycker D, Malin J, Barron R et al (2011) Comparative effectiveness of filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, and sargramostim as prophylaxis against hospitalization for neutropenic complications in cancer chemotherapy patients. Am J Clin Oncol. doi:10.1097/COC.0b013e31820dc075

Morrison VA, Wong M, Hershman D et al (2007) Observational study of the prevalence of febrile neutropenia in patients who received filgrastim or pegfilgrastim associated with 3–4 week chemotherapy regimens in community oncology practices. J Manag Care Pharm 13(4):337–348

Amgen Inc. (2009) Neupogen (filgrastim) prescribing information, Thousand Oaks, CA

Green MD, Koelbl H, Baselga J et al (2003) A randomized double-blind multicenter phase III study of fixed-dose single-administration pegfilgrastim versus daily filgrastim in patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 14(1):29–35

Holmes FA, O'Shaughnessy JA, Vukelja S et al (2002) Blinded, randomized, multicenter study to evaluate single administration pegfilgrastim once per cycle versus daily filgrastim as an adjunct to chemotherapy in patients with high-risk stage II or stage III/IV breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 20(3):727–731

Vogel CL, Wojtukiewicz MZ, Carroll RR et al (2005) First and subsequent cycle use of pegfilgrastim prevents febrile neutropenia in patients with breast cancer: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol 23(6):1178–1184

Trillet-Lenoir V, Green J, Manegold C et al (1993) Recombinant granulocyte colony stimulating factor reduces the infectious complications of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer 29A:319–324

Crawford J, Ozer H, Stoller R et al (1991) Reduction by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor of fever and neutropenia induced by chemotherapy in patients with small-cell lung cancer. NEJM 325:164–170

Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Kartashov A et al (2012) Risk and healthcare costs of chemotherapy-induced neutropenic complications in women with metastatic breast cancer. Chemotherapy 58:8–18

Schuman S, Lambrou N, Robson K et al (2009) Pegfilgrastim dosing on same day as myelosuppressive chemotherapy for ovarian or primary peritoneal cancer. Support Oncol 7(6):225–228

Lokich J (2006) Same day pegfilgrastim and CHOP chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Am J Clin Oncol 29(4):361–363

Hoffman P (2005) Administration of pegfilgrastim on the same day or next day of chemotherapy. ASCO American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting #8137 (Abstract)

Li Y, Klippel ZK, Shih X et al (2015) Effect timing of pegfilgrastim administration on absolute neutrophil count (ANC) trajectory among cancer patients (PTS) receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 33(supple):e20674, Abstract

Burris H III, Belani C, Kaufman P et al (2010) Pegfilgrastim on the same day versus next day of chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer, ovarian cancer, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results of four multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase II studies. J Oncol Pract 6(3):133–140

Skarlos DV, Timotheadou E, Galani E et al (2009) Pegfilgrastim administered on the same day with dose-dense adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer is associated with a higher incidence of febrile neutropenia as compared to conventional growth factor support: matched case-control study of the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group. Oncology 77(2):107–112

Cheng C, Gallagher EM, Yeh J-Y et al (2014) Rates of febrile neutropenia with pegfilgrastim on same day versus next day of CHOP with or without rituximab. Anti-Cancer Drugs 25(8):964–969

Whitworth JM, Matthews KS, Shipman KA et al (2009) The safety and efficacy of day 1 versus day 2 administration of pegfilgrastim in patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy for gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol 112(3):601–604

Gupta NK, Thorpe S, Vanderhoff P et al (2007) Pegfilgrastim can be effectively administered the same day as chemotherapy to prevent neutropenia-related complications. J Clin Oncol 25(18S):19571

Belani CP, Ramalingam S, Al-Janadi A, Eskander E, Ghazal H, Schwartzberg L et al (2006) A randomized double-blind phase II study to evaluate same-day vs next-day administration of pegfilgrastim with carboplatin and docetaxel in patients with NSCLC. J Clin Oncol 24(suppl):7110, abstract

Saven A, Schwartzberg L, Kaywin P et al (2006) Randomized, double-blind, phase 2, study evaluating same-day vs next-day administration of pegfilgrastim with R-CHOP in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol 24(suppl):7570, Abstract

Kaufman PA, Paroly W, Rinaldi D (2004) Randomized double blind phase 2 study evaluating same-day vs. next-day administration of pegfilgrastim with docetaxel, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (TAC) in women with early stage and advanced breast cancer. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. Breast Cancer Res Treat; 88. [Abstract 1054]

US Department of Health and Human Services (2009) Code of Federal Regulations: Title 45, public welfare; Part 46, protection of human subjects. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html. Accessed 4 July 2013

Weycker D, Li X, Edelsberg J et al (2015) Risk and consequences of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in patients with metastatic solid tumors. J Oncol Pract 11(1):47–54

Langeberg W, Siozon CC, Page JH et al (2014) Use of pegfilgrastim primary prophylaxis and risk of infection, by chemotherapy cycle and regimen, among patients with breast cancer or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Support Care Cancer 22(8):2167–2175

Weycker D, Sofrygin O, Seefeld K et al (2013) Technical evaluation of methods for identifying chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in healthcare claims databases. BMC Health Serv Res 13:60

Dulisse B, Li X, Gayle JA et al (2013) A retrospective study of the clinical and economic burden during hospitalizations among cancer patients with febrile neutropenia. J Med Econ 16(6):1–16

Weycker D, Malin J, Edelsberg J et al (2008) Cost of neutropenic complications of chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 19(3):454–460

Lyman GH, Morrison VA, Dale DC et al (2003) Risk of febrile neutropenia among patients with intermediate-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma receiving CHOP chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma 44:2069–2076

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions

Authorship was designated based on the guidelines promulgated by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (2004). All persons who meet the criteria for authorship are listed as authors on the title page. The contribution of each of these persons to this study is as follows: (1) conception and design (Barron, Li, Weycker), acquisition of the data (Li, Weycker), and analysis or interpretation of the data (all authors) and (2) preparation of the manuscript (Figueredo, Weycker) and critical review of the manuscript (Barron, Hagiwara, Li, Tzivelekis). The study sponsor reviewed the study research plan and study manuscript; data management, processing, and analyses were conducted by PAI, and all final analytic decisions were made by study investigators. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declaration of funding

Funding for this research was provided by Amgen Inc. to Policy Analysis Inc. (PAI).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Jacqueline Figueredo, May Hagiwara, and Derek Weycker are employed by PAI. Rich Barron, Xiaoyan Li, and Spiros Tzivelekis are employed by Amgen Inc.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Weycker, D., Li, X., Figueredo, J. et al. Risk of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in cancer patients receiving pegfilgrastim prophylaxis: does timing of administration matter?. Support Care Cancer 24, 2309–2316 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3036-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3036-7