Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to chart patterns of simultaneous trajectories over 8 months in breast cancer survivors’ (BCS) supportive care needs, psychological distress, social support, and posttraumatic growth. Clusters of BCS among these trajectories were identified and characterized.

Methods

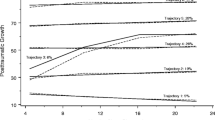

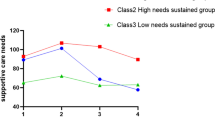

Of 426 BCS study participants, 277 (65 %) provided full assessments in the last week of primary cancer treatment and 4 and 8 months later. Latent trajectories were obtained using growth mixture modeling for patients who responded to all scores for at least one time point (n = 348). Then, classification of BCS was performed by hierarchical agglomerative clustering on axes derived from a multiple factor analysis of trajectory assignments. Self-esteem, attachment security, and satisfaction with care were assessed at baseline.

Results

Four trajectory clusters were identified, including two BCS subgroups (63 %) with low needs and low psychological distress. Two others (37 %) exhibited high or increasing needs and concerning levels of psychological distress. These latter clusters were characterized by higher insecure attachment, lower satisfaction with care, and either lower education or younger age, and having undergone chemotherapy.

Conclusion

More than a third of BCS present unfavorable patterns in supportive care needs over 8 months after primary cancer treatment. Identified psychosocial and cancer care characteristics point to targets for enhanced BCS supportive care.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gysels M, Higginson IJ, Rajasekaran M, Davies E, Harding R (2004) Improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer: research evidence. National Institute of Clinical Excellence & Kings College London, London

Burris JL, Armeson K, Sterba KR (2014) A closer look at unmet needs at the end of primary treatment for breast cancer: a longitudinal pilot study. Behav Med: 1-8

Liao MN, Chen SC, Lin YC et al (2012) Changes and predictors of unmet supportive care needs in Taiwanese women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 39:E380–E389

Minstrell M, Winzenberg T, Rankin N, Hughes C, Walker J (2008) Supportive care of rural women with breast cancer in Tasmania, Australia: changing needs over time. Psychooncology 17:58–65

von Heymann-Horan AB, Dalton SO, Dziekanska A et al (2013) Unmet needs of women with breast cancer during and after primary treatment: a prospective study in Denmark. Acta Oncol 52:382–390

Fiszer C, Dolbeault S, Sultan S, Brédart A (2014) Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: a systematic review: prevalence and predictors of supportive care needs in breast cancer. Psychooncology 23(4):361–374

Bower JE (2008) Behavioral symptoms in patients with breast cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol 26(5):768–777

Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL (2004) Quality of life at the end of primary treatment of breast cancer: first results from the moving beyond cancer randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 96:376–387

Arndt V, Merx H, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H (2005) Persistence of restrictions in quality of life from the first to the third year after diagnosis in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:4945–4953

Liu J-E, Wang H-Y, Wang M-L, Su Y-L, Wang P-L (2014) Posttraumatic growth and psychological distress in Chinese early-stage breast cancer survivors: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology 23(4):437–443

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG (2004) Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq 15(1):1–18

Mehnert A, Koch U (2008) Psychological comorbidity and health-related quality of life and its association with awareness, utilization, and need for psychosocial support in a cancer register-based sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res 64:383–391

Hopwood P, Sumo G, Mills J, Haviland J, Bliss JM (2010) The course of anxiety and depression over 5 years of follow-up and risk factors in women with early breast cancer: results from the UK Standardisation of Radiotherapy Trials (START). Breast 19(2):84–91

Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al.: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2011 [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; April 2014. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/

Allen JD, Savadatti S, Levy AG (2009) The transition from breast cancer ‘patient’ to ‘survivor’. Psychooncology 18:71–78

Schmid-Buchi S, Halfens RJ, Dassen T, van den Borne B (2011) Psychosocial problems and needs of posttreatment patients with breast cancer and their relatives. Eur J Oncol Nurs 15:260–266

Pauwels EE, Charlier C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lechner L, Van Hoof E (2013) Care needs after primary breast cancer treatment. Survivors’ associated sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Psychooncology 22:125–132

Lam WW, Shing YT, Bonanno GA, Mancini AD, Fielding R (2012) Distress trajectories at the first year diagnosis of breast cancer in relation to 6 years survivorship. Psychooncology 21:90–99

Helgeson VS, Snyder P, Seltman H (2004) Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychol 23(1):3–15

Henselmans I, Helgeson VS, Seltman H, de Vries J, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV (2010) Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol 29(2):160–168

Dunn LB, Cooper BA, Neuhaus J et al (2011) Identification of distinct depressive symptom trajectories in women following surgery for breast cancer. Health Psychol 30:683–692

Lam WWT, Bonanno GA, Mancini AD et al (2010) Trajectories of psychological distress among Chinese women diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology 19(10):1044–1051

Wang AW-T, Chang C-S, Chen S-T, Chen D-R, Hsu W-Y (2014) Identification of posttraumatic growth trajectories in the first year after breast cancer surgery. Psychooncology. doi:10.1002/pon.3577

McDonough MH, Sabiston CM, Wrosch C (2014) Predicting changes in posttraumatic growth and subjective well-being among breast cancer survivors: the role of social support and stress. Psychooncology 23(1):114–120.

Wang F, Liu J, Liu L et al (2014) The status and correlates of depression and anxiety among breast-cancer survivors in Eastern China: a population-based, cross-sectional case–control study. BMC Public Health 14:326

Nicholls W, Hulbert-Williams N, Bramwell R (2014) The role of relationship attachment in psychological adjustment to cancer in patients and caregivers: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology 23(10):1083–1095

Bredart A, Kop JL, Griesser AC et al (2013) Assessment of needs, health-related quality of life, and satisfaction with care in breast cancer patients to better target supportive care. Ann Oncol 24:2151–2158

Boyes A, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C (2009) Brief assessment of adult cancer patients’ perceived needs: development and validation of the 34-item Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34). J Eval Clin Pract 15(4):602–606

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG (1996) The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress 9(3):455–471

Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR (1987) A brief measure of social support: practical and theoretical implications. J Soc Pers Relat 4(4):497–510

Rosenberg M (1965) Society and adolescent child. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Lo C, Walsh A, Mikulincer M, Gagliese L, Zimmermann C, Rodin G (2009) Measuring attachment security in patients with advanced cancer: psychometric properties of a modified and brief experiences in close relationships scale. Psychooncology 18(5):490–499

Brédart A, Bottomley A, Blazeby JM et al (2005) An international prospective study of the EORTC cancer in-patient satisfaction with care measure (EORTC IN-PATSAT32). Eur J Cancer 41:2120–2131

Muthén B, Shedden K (1999) Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics 55(2):463–469

Enders CK (2001) The performance of the full information maximum likelihood estimator in multiple regression models with missing data. Educat Psych Measur 61(5):713–740

Sclove SL (1987) Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika 52(3):333–343

Tofighi D, Enders CK (2008) Identifying the correct number of classes in growth mixture models. advances in latent variable mixture models. Information Age Pub, Charlotte

Kim S-Y (2014) Determining the number of latent classes in single- and multi-phase growth mixture models. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J 21(2):263–279

Celeux G, Soromenho G (1996) An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. J Classif 3(2):195–212

Escofier B, Pagès J (1994) Multiple factor analysis (AFMULT package). Comput Stat Data Anal 18(1):121–140

Lê S, Josse J, Husson F et al (2008) FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J Stat Softw 25(1):1–18

Lam WWT, Tsang J, Yeo W et al (2014) The evolution of supportive care needs trajectories in women with advanced breast cancer during the 12 months following diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 22(3):635–644

Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Bower JE, Belin TR (2011) Physical and psychosocial recovery in the year after primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:1101–1109

Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G et al (2011) Evaluating survivorship care plans: results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:4755–4762

Acknowledgments

This study is granted by the French National Cancer League and the French Ile-de-France region Cancerpole. The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Gariné Catanasian, Catherine Gravigny, Marie Jézéquel, and Sophie Simandoux for their assistance in recruiting patients. We thank Leslie Elliott for her linguistic revision of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brédart, A., Merdy, O., Sigal-Zafrani, B. et al. Identifying trajectory clusters in breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs, psychosocial difficulties, and resources from the completion of primary treatment to 8 months later. Support Care Cancer 24, 357–366 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2799-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2799-1