Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of prolonged-release oxycodone/naloxone (OXN PR) and its impact on quality of life (QoL), in patients with moderate-to-severe cancer pain.

Methods

This was an open-label extension (OLE) of a 4 week, randomized, double-blind (DB) study in which patients with moderate-to-severe cancer pain had been randomized to OXN PR or oxycodone PR (OxyPR). During the OLE phase, patients were treated with OXN PR capsules (≤20/60 mg/day) for ≤24 weeks. Outcome measures included safety, efficacy and QoL.

Results

One hundred and twenty-eight patients entered the OLE, average pain scores based on the modified Brief Pain Inventory—Short Form were low and stable over the 24-week period. The improvement in bowel function and constipation symptoms as measured by the Bowel Function Index and patient assessment of constipation in patients treated with OXN PR during the 4-week DB study was maintained. In patients treated with OxyPR during the DB phase, bowel function and constipation symptoms were improved during the OLE. In the DB and in the OLE, health status and QoL were similar for patients treated with OXN PR and OxyPR. There were no unexpected safety or tolerability issues.

Conclusions

In patients with moderate-to-severe cancer pain, long-term use of OXN PR is well tolerated and effective, resulting in sustained analgesia, improved bowel function and improved symptoms of constipation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pain is a common and debilitating symptom of cancer and can significantly impact the lives of patients through detrimental effects on physical functioning, psychological well-being and social interactions [1]. Pain affects a large proportion of cancer patients, with prevalence rates ranging from 33 % in patients after curative treatment to 64 % in patients with advanced, metastatic or terminal phase disease [2, 3]. In a 2009 European survey, 56 % of cancer patients were demonstrated to suffer pain several times per month, with over 90 % of these reporting their pain as moderate to severe in intensity [4].

Opioid analgesics are the established treatment for the relief of moderate-to-severe cancer pain and several different opioids are now available [5, 6]. For years, morphine has been the accepted gold standard for the treatment of cancer pain and is endorsed by the European Association of Palliative Care [6]. Oxycodone (a semi-synthetic opioid analgesic) has proven efficacy in the management of severe pain of different aetiologies [7–10]. A series of systematic reviews on the use of opioids in cancer patients found that oxycodone and hydromorphone have efficacy and tolerability profiles comparable with that of morphine [11, 12].

Although opioids have proven analgesic efficacy, their use is frequently complicated by a range of side effects, which include nausea, sedation, euphoria/dysphoria, constipation and itching [13, 14]. The most common and often most debilitating side effect is opioid-induced bowel dysfunction (OIBD), which comprises a constellation of gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events (AEs) including constipation, hard dry stools, straining, incomplete evacuation, bloating, abdominal cramping, abdominal distension and increased gastric reflux [13, 15]. The primary symptom of OIBD is constipation, which occurs in approximately 90 % of cancer patients receiving opioid therapy and persists over time [14, 16, 17]. Current strategies to manage OIBD are non-specific and frequently ineffective [18]. Increasing dietary fibre, fluid intake and physical mobility are usually insufficient to prevent or treat OIBD and the majority of patients receiving long-term opioid therapy require laxatives [13]. Laxatives do not address the underlying opioid receptor-mediated cause of constipation and evidence for their effectiveness is weak; therefore, OIC persists in many patients [13, 19].

A novel therapeutic approach to bypass the GI effects of opioids involves co-administration of an opioid antagonist (naloxone). When administered orally in a prolonged-release (PR) formulation, naloxone has a low systemic bioavailability (<3 %) and antagonises peripheral opioid receptors in the GI tract with little impact on centrally-acting opioid analgesia [20–22]. Oral naloxone can, therefore, improve OIC [23, 24]. In patients with moderate-to-severe non-cancer pain, randomized phase III trials have demonstrated that co-administration of prolonged-release (PR) oxycodone with naloxone (OXN PR) provides effective analgesia whilst significantly reducing the impact of OIBD and OIC compared with oxycodone PR alone (OxyPR) [25–27] and that this effect is maintained over the long term (≤52 weeks) [28]. Similar safety and efficacy has been demonstrated in a randomized phase II study of OxyPR vs OXN PR in patients with moderate-to-severe cancer pain [29]; although, the long-term effects on this patient population has not yet been demonstrated. Here, we report results of a long-term open-label extension (OLE) of the phase II study in which patients were maintained on or switched to OXN PR.

Methods

Study design

This was a 24 week, uncontrolled, open-label extension of a 4 week, randomized, double-blind study (OXN2001S; NCT00513656) [29] conducted to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of OXN PR vs OxyPR in patients with moderate-to-severe cancer pain. The study was performed in compliance with good clinical practice and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients completing the double-blind period and those who had discontinued prematurely due to constipation were eligible to enter the OLE phase. Patients aged ≥18 years were enrolled into the double-blind phase of the study if they had moderate-to-severe chronic cancer pain that required ‘round-the-clock’ opioid therapy and constipation secondary to opioid therapy [29].

Study treatment

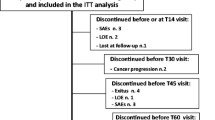

During the double-blind phase, participants were randomized to OXN PR or OxyPR for 4 weeks (≤120 mg/day). During the OLE, all patients received OXN PR every 12 h for ≤24 weeks). Study Visit 9a (Day 1) was the first visit of the OLE phase of the study and typically occurred on the same day as Visit 9 (end of the double-blind phase) (Figure 1A).

Study design (A) and patient disposition (B). AEs adverse events, n number of patients; OLE open-label extension, OXN PR prolonged-release oxycodone/naloxone tablets, OxyPR prolonged-release oxycodone tablets, R randomization, V visit, WK week. Superscript letter a indicates day or week since the beginning of the open-label extension phase; V9a was the first visit of the open-label extension phase and typically occurred on the same day as visit 9 (end of double-blind phase). Superscript letter b includes two patients who discontinued from the double-blind phase due to constipation and entered the OLE phase

The initial starting dose was the effective analgesic dose based on oxycodone or OXN PR that the patient was on at the end of the double-blind phase. Any patient on a dose of ≤80 mg/day OxyPR was switched directly to OXN PR. For example, all patients on 80 mg/day OxyPR started with a daily dose of OXN PR 80/40 mg. Those patients on >80 mg/day OxyPR were switched to OXN PR in a stepwise manner. All patients receiving 90, 100, 110, or 120 mg/day OxyPR were started on OXN PR 40/20 mg 12 hourly with the remainder of their oxycodone dose given as OxyPR. Dose titration was permitted at the discretion of the investigator to ≤120/60 mg/day. A total of 19 patients received OXN PR at a daily dose of >80/40 mg; safety findings for these patients were no different from the whole population.

Rescue medications (Oxy IR 5 mg and laxative bisacodyl 5 mg) were supplied for the first 7 days of the study. After 7 days, laxative use was documented as concomitant medication.

Study assessments

Efficacy was evaluated based on the following measurements: Brief Pain Inventory—Short Form (BPI-SF), a patient-rated scale based on ‘least’, ‘average’ and ‘worst’ pain felt over the previous week [30]; Bowel Function Index (BFI) a comprising three components (ease of defecation, feeling of incomplete bowel evacuations and personal judgement of constipation) [31, 32]; patient assessment of constipation (PAC-SYM) [33]; rescue medications (Oxy IR and laxative); number of bowel movements; health status (EuroQol EQ-5D) and quality of life (QoL) (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30; EORTC QLQ-C30) [34, 35]. Safety assessments included adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs, physical and laboratory evaluations, 12-lead electrocardiograph, and evaluation of the symptoms of opiate withdrawal as measured by the Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) collected 1 day and 1 week following the start of the OLE [36].

aCopyright for the BFI is owned by Mundipharma Laboratories GmbH, Switzerland, 2002; the BFI is subject of European Patent Application Publication No. EP 1,860,988 and corresponding patents and applications in other countries.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed on the OLE safety population (patients who received at least one dose of study medication during the OLE. All efficacy and safety variables were summarized descriptively. All continuous variables were summarized using the following descriptive statistics: n, mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum and maximum. The frequency and percentage of observed levels were reported for all categorical measures.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 128 patients entered the OLE phase of which 126 (98.4 %) had previously completed the double-blind phase and 2 (1.6 %) had discontinued due to constipation. All 128 patients in the OLE phase received study medication and 68 patients (53.1 %) completed the study. Fifty-three per cent and 56.9 % of patients were male and female, respectively, and the mean age was 62.5 years. The most common cancers were breast (19.5 %), lung (8.6 %) and prostate (11.7 %) (Table 1).

Efficacy

OXN PR dose

Mean duration of exposure to OXN PR was 122.2 days and the mean daily dose was 56.2 mg. The majority of subjects (69.5 %) remained on their starting dose for the duration of the study. Thirty-four subjects progressed to a slightly higher dose (usually 10 or 20 mg or higher) by the end of the study/discontinuation.

Pain (BPI-SF)

At the end of the double-blind phase of the study in which patients were treated with OxyPR or OXN PR, there was no significant difference in pain control (as assessed by the BPI-SF) between the two treatments [29]. At the beginning of the OLE, BPI-SF pain scores for ‘average pain’ were low in both groups: mean (SD) 3.42 (2.03) and 3.63 (1.76) for OXN PR and OxyPR, respectively. BPI-SF scores remained consistently low and stable in both groups over the OLE period with scores of 3.71 (2.12) for OxyPR and 3.56 (2.27) for OXN PR at Week 24 (Figure 2).

BPI-SF average pain scores (LOCF) by study visit (OLE safety population). BPI-SF Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form, LOCF last observation carried forward, OLE open-label extension, OXN PR prolonged-release oxycodone/naloxone tablets, OxyPR prolonged-release oxycodone tablets, SD standard deviation. Superscript letter a indicates day or week since the beginning of the open-label extension phase. Data for the DB period are based on the per protocol population (LOCF): OXN PR, n = 62 OxyPR, n = 71; higher scores indicate more severe pain (0 no pain, 10 most severe pain)

Bowel function index

At the end of the double-blind phase, OXN PR is both statistically significantly superior in respect to BFI and has also demonstrated a change that is clinically relevant compared with OxyPR [29]. For patients that received OXN PR during the DB phase (OLE baseline score [SD]: 38.08 [26.94]), the improvement in BFI was maintained during the OLE (mean BFI: 37.90 [28.06] at Week 12 and 39.02 [27.70] at Week 24). For patients treated with OxyPR during the DB phase (OLE baseline score: 46.61 [26.84]), mean BFI scores were reduced to 38.52 (27.69) at Week 12 and 38.78 (27.45) at Week 24, comparable to those who had previously received OXN PR (Figure 3).

BFI scores (LOCF) by study visit (OLE safety population). BFI bowel function index, LOCF last observation carried forward, OLE open-label extension, OXN PR prolonged-release oxycodone/naloxone tablets, OxyPR prolonged-release oxycodone tablets, SD standard deviation. Superscript letter a indicates day or week since the beginning of the open-label extension phase. Data for the DB period are based on the full analysis population (LOCF); OXN PR, n = 77; OxyPR, n = 80; higher scores indicate more severe constipation

Constipation symptoms (PAC-SYM)

At the end of the double-blind phase, a statistically significantly greater improvement in constipation symptoms was observed for OXN PR compared with OxyPR [29]. At the beginning of the OLE phase, mean (SD) PAC-SYM total symptoms scores were 10.55 (8.60) and 15.53 (10.20) for OXN PR and OxyPR, respectively. The improvement in constipation symptoms seen in the OXN PR group was maintained during the OLE, with a mean PAC-SYM (SD) of 12.14 (9.65) at Week 24. For patients who had received OxyPR during the double-blind period, mean PAC-SYM scores were reduced to 12.81 (10.10) at Week 24 (Table 2).

Rescue medication

During the first 7 days of the OLE, the need for rescue medication was low. A total of 37.5 % of patients used laxatives. The mean bisacodyl dose in 7 days was 6.09 mg, which translates to approximately one tablet used in 7 days. A mean of 1.1 (range: 0–3.9) capsules of Oxy IR 5 mg were required for rescue analgesia per day.

QoL

In the double-blind phase of the study, health status and QoL were similar between OXN PR and OxyPR groups [29]. These results were maintained during the OLE. In the total OLE population, the mean (SD) EQ-5D index score was 0.49 (0.31) at day 1, 0.59 (0.25) at week 12 and 0.46 (0.38) at week 24. The EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status scores were 45.83 (20.36) at day 1, 53.08 (20.07) at week 12 and 43.06 (23.90) at week 24. For the specific EORTC constipation scale, the score was at least maintained and suggested an improvement over the OLE with mean (SD) scores in the total OLE population of 45.31 (35.18) at day 1, 38.49 (35.66) at week 12 and 42.71 (34.44) at week 24.

Safety

Overall, 93.8 % of patients experienced at least one AE in the OLE phase of which 28.1 % were classed as having AEs related to study treatment according to investigators. Fifty-nine patients (46.1 %) experienced serious adverse events (SAEs). A total of four SAEs in four patients were related to study treatment: constipation, dyspnoea, paralytic ileus and worsening of cancer-related pain. Two additional SAEs in one patient were assessed as treatment-related by the sponsor. A total of 38 patients discontinued during the OLE. In total, 28 patients (21.9 %) died during the study. Twenty-four of these deaths were due to disease progression or events related to disease progression; the other deaths were due to sepsis, worsening dyspnoea, lung embolism and cardiac arrest. The death from worsening of dyspnoea was recorded as unlikely to be related to study medication. All other deaths were recorded as unrelated to study medication. There were no clinically important changes in vital signs, laboratory values and electrocardiographs. Mean (SD) SOWS scores in the OLE safety population were comparable with those collected in the respective double-blind phase and decreased from 7.90 (7.39) at day 1 to 7.36 (6.24) at week 1 of the OLE. SOWS scores were comparable in both patient groups of the double-blind phase (Table 3).

Discussion

Pain is a common symptom of cancer, and if poorly treated, can adversely affect patients’ physical functioning, psychological well-being and social interactions [4]. Whilst opioids are widely recommended to relieve pain in cancer patients [6, 37], successful management requires that the benefits of these agents outweigh the impact of treatment-related side effects [38]. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction, particularly OIC, is the most frequently reported AE experienced by patients receiving long-term opioid therapy and can be sufficiently severe to undermine the effectiveness of pain management [13].

To our knowledge, this OLE study is the largest trial to date evaluating OIC in cancer pain and provides a sound basis for evaluation of long-term safety and efficacy data. Results from this study demonstrate that long-term treatment (of at least 6 months) with OXN PR provides sustained analgesic efficacy for patients with moderate-to-severe cancer pain whilst maintaining improved bowel function. Increases in doses were small and there were no withdrawals due to lack of therapeutic effect indicating that pain control was maintained for the duration of the study for most subjects. The average pain scores based on the modified BPI-SF were low and stable over the 24-week OLE, indicating good analgesic efficacy during long-term treatment with OXN PR. The use of rescue medication was low and did not lead to any concern over the switching from OxyPR to OXN PR. The improvement in bowel function demonstrated with OXN PR during the double-blind phase of the study was maintained during the 24-week OLE phase, and patients who had received OxyPR during the double-blind period experienced improvement in bowel function following switch to OXN PR. Health status and QoL appeared to be maintained over the course of the OLE, with some possible improvements during the earlier part of the study.

It should be noted that data for QoL at week 24 (visit 13) included patients who had discontinued earlier in the study. Week 12 (visit 12), however, included only those data recorded at the visit. This may have contributed to any observed differences, particularly since the majority of discontinuations were due to disease progression/worsening of the condition and associated AEs.

The safety profile was as expected for this patient population, in accordance with the safety profile of opioid analgesics in this advanced cancer patient population. Although the overall AE and discontinuation rates were high, this was not unexpected considering the patient population and the duration of the study with respect to the course of cancer. The incidence of AEs in the OLE phase was comparable with that in the double-blind phase. The most frequently reported AEs were related to progression of underlying cancer disease, which is reflected in the profile of the frequently reported AEs of malignant neoplasm progression, cancer pain and nausea. The rate of treatment-related AEs (28.1 %) in this cancer study was in line with reported AEs in non-malignant pain populations in OLE studies of OXN PR [28]. Although 59 patients (46.1 %) experienced SAEs, the proportion considered related to study treatment was low (only 4 patients; 3.1 %).

As with any clinical trial, the results of this study should be interpreted with some consideration of its limitations. Open-label extension studies are often uncontrolled and potentially biased due to patient self-selection, and further, randomized trials would better support the long-term use of OXN PR in chronic cancer pain. However, open-label studies, allow for greater patient exposure to medications, which enhances understanding of the efficacy and safety profile of the agent being investigated over a longer time period. As such, these results add to the accumulating evidence for the analgesic efficacy and improvement in bowel function and QoL associated with OXN PR, and suggest that these effects can be maintained during long-term therapy. Overall, the results reported here provide further support for the findings from the 4-week double-blind phase of this trial [29] and are also in line with those seen in patients with non-malignant pain [25–28].

Conclusion

The findings presented here demonstrated that the benefits of OXN PR seen in the double-blind study were maintained in the 24-week OLE. For patients with moderate-to-severe cancer pain, this allows sustained analgesia whilst maintaining improved bowel function and reduced symptoms of constipation. OXN PR was not associated with any unexpected safety or tolerability issues. These findings may reassure clinicians that patients may safely remain on stable drugs for pain as their cancer progresses.

References

Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, Edwards KR, Cleeland CS (1995) When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain 61(2):277–284, Epub 1995/05/01

Ripamonti CI, Santini D, Maranzano E, Berti M, Roila F (2012) Management of cancer pain: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol 23(Suppl 7):139–154, Epub 2012/11/20

van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J (2007) Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol 18(9):1437–1449, Epub 2007/03/16

Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett B, de Conno F, Filbet M, Foubert AJ et al (2009) Cancer-related pain: a pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol 20(8):1420–1433, Epub 2009/02/27

Wiffen PJ (2005) Evidence-based pain management and palliative care in issue one for 2005 of The Cochrane Library. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 19(3):65–68, Epub 2005/10/13

Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, Bennett MI, Brunelli C, Cherny N et al (2012) Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol 13(2):e58–e68, Epub 2012/02/04

Mucci-LoRusso P, Berman BS, Silberstein PT, Citron ML, Bressler L, Weinstein SM et al (1998) Controlled-release oxycodone compared with controlled-release morphine in the treatment of cancer pain: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study. Eur J Pain 2(3):239–249, Epub 2004/04/23

Gimbel JS, Richards P, Portenoy RK (2003) Controlled-release oxycodone for pain in diabetic neuropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology 60(6):927–934, Epub 2003/03/26

Coluzzi F, Mattia C (2005) Oxycodone. Pharmacological profile and clinical data in chronic pain management. Minerva Anestesiol 71(7–8):451–460, Epub 2005/07/14

Kalso E (2005) Oxycodone. J Pain Symptom Manage 29(5 Suppl):S47–S56, Epub 2005/05/24

Caraceni A, Pigni A, Brunelli C (2011) Is oral morphine still the first choice opioid for moderate to severe cancer pain? A systematic review within the European Palliative Care Research Collaborative guidelines project. Palliat Med 25(5):402–409, Epub 2011/06/29

King SJ, Reid C, Forbes K, Hanks G (2011) A systematic review of oxycodone in the management of cancer pain. Palliat Med 25(5):454–470, Epub 2011/06/29

Pappagallo M (2001) Incidence, prevalence, and management of opioid bowel dysfunction. Am J Surg 182(5A Suppl):11S–18S, Epub 2002/01/05

Ballantyne JC (2007) Opioid analgesia: perspectives on right use and utility. Pain Physician 10(3):479–491, Epub 2007/05/26

Panchal SJ, Muller-Schwefe P, Wurzelmann JI (2007) Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: prevalence, pathophysiology and burden. Int J Clin Pract 61(7):1181–1187, Epub 2007/05/10

Mueller-Lissner S (2010) Fixed combination of oxycodone with naloxone: a new way to prevent and treat opioid-induced constipation. Adv Ther 27(9):581–590, Epub 2010/08/18

Mancini I, Bruera E (1998) Constipation in advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 6(4):356–364, Epub 1998/08/08

Kurz A, Sessler DI (2003) Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: pathophysiology and potential new therapies. Drugs 63(7):649–671, Epub 2003/03/27

Ahmedzai SH, Boland J. Constipation in people prescribed opioids. Clin Evid (Online). 2010;2010. Epub 2010/01/01.

Choi YS, Billings JA (2002) Opioid antagonists: a review of their role in palliative care, focusing on use in opioid-related constipation. J Pain Symptom Manage 24(1):71–90, Epub 2002/08/17

De Schepper HU, Cremonini F, Park MI, Camilleri M (2004) Opioids and the gut: pharmacology and current clinical experience. Neurogastroenterol Motil 16(4):383–394, Epub 2004/08/13

Smith K, Hopp M, Mundin G, Bond S, Bailey P, Woodward J et al (2012) Low absolute bioavailability of oral naloxone in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 50(5):360–367, Epub 2012/05/01

Culpepper-Morgan JA, Inturrisi CE, Portenoy RK, Foley K, Houde RW, Marsh F et al (1992) Treatment of opioid-induced constipation with oral naloxone: a pilot study. Clin Pharmacol Ther 52(1):90–95, Epub 1992/07/01

Clemens KE, Mikus G (2010) Combined oral prolonged-release oxycodone and naloxone in opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: review of efficacy and safety data in the treatment of patients experiencing chronic pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother 11(2):297–310, Epub 2009/12/25

Simpson K, Leyendecker P, Hopp M, Muller-Lissner S, Lowenstein O, De Andres J et al (2008) Fixed-ratio combination oxycodone/naloxone compared with oxycodone alone for the relief of opioid-induced constipation in moderate-to-severe noncancer pain. Curr Med Res Opin 24(12):3503–3512, Epub 2008/11/27

Lowenstein O, Leyendecker P, Hopp M, Schutter U, Rogers PD, Uhl R et al (2009) Combined prolonged-release oxycodone and naloxone improves bowel function in patients receiving opioids for moderate-to-severe non-malignant chronic pain: a randomised controlled trial. Expert Opin Pharmacother 10(4):531–543, Epub 2009/02/27

Vondrackova D, Leyendecker P, Meissner W, Hopp M, Szombati I, Hermanns K et al (2008) Analgesic efficacy and safety of oxycodone in combination with naloxone as prolonged release tablets in patients with moderate to severe chronic pain. J Pain 9(12):1144–1154, Epub 2008/08/19

Sandner-Kiesling A, Leyendecker P, Hopp M, Tarau L, Lejcko J, Meissner W et al (2010) Long-term efficacy and safety of combined prolonged-release oxycodone and naloxone in the management of non-cancer chronic pain. Int J Clin Pract 64(6):763–774, Epub 2010/04/08

Ahmedzai SH, Nauck F, Bar-Sela G, Bosse B, Leyendecker P, Hopp M (2012) A randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, double-dummy, parallel-group study to determine the safety and efficacy of oxycodone/naloxone prolonged-release tablets in patients with moderate/severe, chronic cancer pain. Palliat Med 26(1):50–60, Epub 2011/09/23

Cleeland CS, Ryan KM (1994) Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore 23(2):129–138, Epub 1994/03/01

Rentz AM, Yu R, Muller-Lissner S, Leyendecker P (2009) Validation of the bowel function index to detect clinically meaningful changes in opioid-induced constipation. J Med Econ 12(4):371–383, Epub 2009/11/17

Ueberall MA, Muller-Lissner S, Buschmann-Kramm C, Bosse B (2011) The Bowel Function Index for evaluating constipation in pain patients: definition of a reference range for a non-constipated population of pain patients. J Int Med Res 39(1):41–50, Epub 2011/06/16

Frank L, Kleinman L, Farup C, Taylor L, Miner P Jr (1999) Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol 34(9):870–877, Epub 1999/10/16

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376, Epub 1993/03/03

EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16 (3):199–208. Epub 1990/11/05.

Handelsman L, Cochrane KJ, Aronson MJ, Ness R, Rubinstein KJ, Kanof PD (1987) Two new rating scales for opiate withdrawal. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 13(3):293–308, Epub 1987/01/01

Raphael J, Ahmedzai S, Hester J, Urch C, Barrie J, Williams J et al (2010) Cancer pain: part 1: pathophysiology; oncological, pharmacological, and psychological treatments: a perspective from the British pain society endorsed by the UK association of palliative medicine and the Royal College of General Practitioners. Pain Med 11(5):742–764, Epub 2010/06/16

Cherny N, Ripamonti C, Pereira J, Davis C, Fallon M, McQuay H et al (2001) Strategies to manage the adverse effects of oral morphine: an evidence-based report. J Clin Oncol 19(9):2542–2554, Epub 2001/05/02

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Medicus International for providing editorial assistance.

Funding

This study, and the editorial assistance, was funded by Mundipharma Research GmbH & Co. KG.

Disclosures

SA and WL have worked as consultants for Mundipharma Research; ML, HD and MH are employees of Mundipharma Research GmbH.

Conflict of interest

MJ and HP have no conflict of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmedzai, S.H., Leppert, W., Janecki, M. et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of oxycodone/naloxone prolonged-release tablets in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic cancer pain. Support Care Cancer 23, 823–830 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2435-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2435-5