Summary

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate different factors that may contribute to workload and job satisfaction among Austrian pediatricians.

Methods

We conducted an online survey with 16 questions and performed statistical analyses.

Results

Of 375 participating pediatricians, 61% were female, 39% male, 61% clinicians, 21% panel doctors and 12% private doctors. Overall, job satisfaction was moderate (6 ± 2.4 on a positive scale of 0–10). Higher working hours (p = 0.014) and higher patient numbers (p = 0.000) were significantly associated with lower job satisfaction. Lowest satisfaction was described for administrative or other nonmedical work. Lack of time for patient consultation was also correlated with poor satisfaction. Pediatricians older than 65 years reported the highest job satisfaction whereas pediatricians between 55 and 65 years and younger than 36 years showed the lowest scores. Although male pediatricians worked significantly more often more than 40 h per week than females (75% vs. 53%, p = 0.000), female pediatricians were less satisfied about the proportion of administrative (p = 0.015) and other nonmedical work (p = 0.014).

Conclusion

New working models considering less workload, particularly less nonmedical work and intensified collaboration between pediatric clinicians and practitioners are needed to allow more available time per patient, to increase job satisfaction and thus to raise attractivity for pediatric primary care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Stress at work and excessive workload have been the most important occupational health challenges for decades. It is well known that healthcare professionals are exposed to significantly more stress than the general population [1]. The working environment of individual healthcare professionals and thus their individual workload varies widely. Feelings of job stress typically occur when working conditions are perceived to be too challenging to cope with [2]. Constant pathological stress during work leads to adverse consequences for workers’ health, such as mental health syndromes (e.g., burnout), psychosomatic complaints and physical illness [3, 4]. Studies showed that the rates of burnout and dissatisfaction in the medical profession are highest at the beginning and middle of the career [5]. As they advance in career, many medical doctors find better coping strategies and thus partially compensate for the high workload.

Most of these studies dealt with the general dissatisfaction of healthcare professionals. Only few studies dealt specifically with workload and job dissatisfaction and their correlating factors in pediatric medicine.

The working environment of healthcare professionals is constantly changing and the physician has to adapt to new circumstances. Since new technologies, new diagnostic options and new therapeutic concepts arise, pediatricians have to continuously “educate” themselves and adapt to these new circumstances in order to provide state of the art medicine for their young patients [6]. Long working days, psychological and physical stress at work and the pressure to provide top-quality medicine often lead to dissatisfaction and burnout. Studies confirmed the relatively high dissatisfaction among pediatricians and high rates of burnout, which again may lead to serious treatment errors [5, 7,8,9,10]. Finally, dissatisfaction with work environment may lead to complaints and resignation: Knowledge about these facts may subsequently prevent medical students from choosing this specialization (negative role model).

Personal satisfaction is a prerequisite to successfully practice the medical profession. Therefore, in recent years adequate work-life balance has become increasingly important [11]. This study aims to analyze the workload of pediatricians in Austria. In particular, we wanted to elaborate gender and generational differences. The main motivation for this study was the fact that Austria, like other countries, faces the problem to sustain pediatric primary care [12].

Methods

An online survey was created using SurveyMonkey® (Momentive Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA) and an email invitation was sent to all members of the Austrian Society of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine in February 2020.

The survey comprised 3 personal questions including age, gender and workplace, 2 questions related to workload (average working time per week and average number of patients per week), 1 question about the collaboration between pediatric clinicians and practitioners and 10 questions related to job satisfaction. Questions about job satisfaction were answered on a scale of 0 (not at all satisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) and captured overall job satisfaction and several aspects that potentially contribute to job satisfaction: satisfaction with personal work-life balance, time for patient consultation, the proportion of administrative work and other nonmedical work, income and economic pressure, further and continuing education, working alone and the possibility to exchange knowledge and opinions with colleagues.

A total of 375 pediatricians (22% return rate) participated in this survey.

We used the χ2-test to compare frequency distributions between two categorical variables. Differences between groups were tested with Student’s t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA). To assess linear correlations between two variables Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used. Statistical analyses and creation of graphs were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Austrian Society of Pediatrics. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Characteristics of all 375 responding pediatricians are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants were female (61%) and working in hospitals (61%). Significantly more females (77% and 69%) were represented within the young age groups (25–35 years and 36–45 years, respectively), while in the older age group (> 65 years) more males (78%) were represented. Most doctors (62%) reported more than 40 working hours per week. Males worked significantly more often above 40 h per week than females (74.8% vs. 53.3%, p = 0.000). Pediatricians older than 65 years worked significantly less often above 40 h per week than all other age groups (p = 0.000).

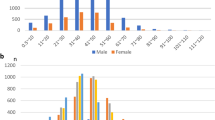

Pediatricans in hospitals worked significantly more often above 40 h per week than pediatricians in panel practices and private practices (p = 0.000). Pediatricians in panel practices worked more than pediatricians in private practices (p = 0.002). Furthermore, in panel practices more patients were seen per day compared to private practices (p = 0.000) or hospitals (p = 0.000). Overall, job satisfaction was moderate (6.0 ± 2.4 on a positive scale of 0–10). Pediatricians older than 65 years reported the highest job satisfaction, whereas pediatricians between 55–65 years and younger than 36 years showed the lowest scores (Fig. 1). Job satisfaction was significantly lower in panel practices (5.8 ± 0.3) and in hospitals (5.6 ± 0.2) compared to private practices (7.7 ± 0.3, p = 0.000).

Lowest satisfaction was described for administrative work (3.0 ± 2.3) and other nonmedical work (2.9 ± 2.5). Interestingly, this satisfaction was significantly lower in females than in males (p = 0.015 and p = 0.014, respectively, see Table 2).

Higher working hours (p = 0.014) and higher patient numbers (p = 0.000) were significantly associated with lower job satisfaction. Similarly, other aspects of job satisfaction were associated with workload (Table 3). Higher working hours were significantly associated with dissatisfaction with personal work-life balance (p = 0.000), the lack of time for patient consultation (p = 0.000), the proportion of administrative work (p = 0.000) and the proportion of nonmedical work (p = 0.000). Higher patient numbers were significantly associated with dissatisfaction with personal work-life balance (p = 0.002), the lack of time for patient consultation (p = 0.000) and the possibility to exchange knowledge with colleagues (p = 0.000).

Discussion

We present the results of the first Austrian survey among pediatricians on job satisfaction with the main focus on gender and generational aspects. Thus far, there are only few studies on this topic worldwide and our results are mostly in line with data from these studies.

One limitation of our study is a response rate of 22%. Non-response might implicate potential bias. As the characteristics of our participants are very similar to characteristics of all members of the Austrian Society of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (e.g., about 40% working in practices, < 20% below 35 years) we assume that this sample size is representative.

In our survey, most participants were female and at younger age, indicating that the field of pediatrics is very popular among young female doctors in Austria. This result is consistent with other studies [13,14,15]. Most pediatricians work more than 40 h a week, which is again in line with other studies showing that healthcare professionals spend more time at work than the average population [7, 16, 17]. The finding that males work significantly more often above 40 h per week than females may at least in part be explained by the higher number of women in part-time employment.

Overall, our survey showed an average level of 6 (on a scale of 0–10) for job satisfaction. Interestingly, pediatricians over 65 years of age showed the highest satisfaction, while early career pediatricians between the ages of 25 and 35 years reported the least satisfaction with work-life balance and overall job satisfaction. Also, this finding is in line with other studies and may be explained by the challenges at the beginning of the career. Recent studies from the USA have found that burnout rates and psychological stress are markedly higher amongst practicing physicians than in individuals in other careers, even when adjusting for working hours and other factors [7, 18, 19]. That means that the entry into a medical career is apparently particularly challenging. Life conditions may change dramatically and early career physicians have to take substantial responsibility within a very short time. The first night shifts may represent another burden. The first years of employment are therefore often characterized by disillusionment, self-doubt, disorientation and fear [17, 20,21,22]. In the further course, most pediatricians gain self-confidence and acquire further specialist knowledge, which helps to manage stress and to build resilience; however, in the middle years of the professional career other major challenges can have a negative impact on job satisfaction. Many doctors in private practice have to repay their loans for their practices. In private life, family planning and childcare may play a role, compatibility of family and work seems to be an essential cornerstone. The still relatively low job satisfaction of this age group may be explained by these factors.

Another interesting finding is the relatively low level (and a wide range) of job satisfaction in the age group 55–65 years. This may be interpreted as a kind of end of career dissatisfaction and the lack of positive future visions for many colleagues. In contrast, the clearly higher satisfaction level (and a narrow range) in the age group 65+years may be a hint that pediatricians voluntarily staying in their job over the age of 65 years are those who are primarily more satisfied and thus continue working. The finding that this age group worked significantly less often more than 40 working hours per week than all the other age groups might be a factor contributing to higher job satisfaction since we could show a clear overall association between less workload and higher job satisfaction. Interestingly, job satisfaction was higher in pediatricians older than 65 years regardless of workplace, however, sample size was low.

In all age groups, the lowest satisfaction was described for administrative work and other nonmedical work. It is a fact that the amount of doctors’ administrative work (such as documentation, writing letters, coordinating appointments) is steadily increasing, reducing the time left for medical tasks (such as interventions and special procedures) and direct patient contact.

Our survey did not show differences in overall job satisfaction between female and male pediatricians; however, females were significantly less satisfied with the proportion of administrative and nonmedical work than men. This finding suggests that female doctors are more engaged with administrative and nonmedical tasks, which could be explained by the fact that women are often employed in part-time positions after returning from maternal leave. The reason for this remains unclear and needs to be further addressed.

In our study, we found a clear association between high patient numbers and dissatisfaction with work-life balance and the possibility to exchange knowledge with colleagues. 90% of responders stated their wish for close cooperation with the regional children’s hospital(s) including repeated in-hospital training and possibly job rotation. Research on resilience indicates that such exchange of knowledge with colleagues and support within networks are important factors for job satisfaction and burnout prevention [23].

We could clearly see an association between higher workload in hospitals and panel practices and lower job satisfaction compared to private practices. This association needs to be addressed by policy and decision makers. The shortage of primary care pediatricians currently seen in several European countries enforces to develop new models of provision [24, 25]. These should consider the wishes and visions of the future generation of pediatricians.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that less workload, particularly less administrative and other nonmedical work, more time for individual patients as well as intensified collaboration between pediatric clinicians and primary care pediatricians are important aspects to increase job satisfaction and thus to raise attractivity of paediatric primary care.

References

Bridgeman PJ, Bridgeman MB, Barone J. Burnout syndrome among healthcare professionals. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(3):147–52.

Stanisławski K. The coping circumplex model: an integrative model of the structure of coping with stress. Front Psychol. 2019;10:694.

Jung J, Jeong I, Lee K‑J, Won G, Park JB. Effects of changes in occupational stress on the depressive symptoms of Korean workers in a large company: a longitudinal survey. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2018;30:39.

Moreno Fortes A, Tian L, Huebner ES. Occupational stress and employees complete mental health: a cross-cultural empirical study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3629.

Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1358–67.

Starmer AJ, Duby JC, Slaw KM, Edwards A, Leslie LK. Pediatrics in the year 2020 and beyond: preparing for plausible futures. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):971–81.

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–85.

Schneider SE, Phillips WM. Depression and anxiety in medical, surgical, and pediatric interns. Psychol Rep. 1993;72(3 Pt 2):1145–6.

Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, Sharek PJ, Lewin D, Chiang VW, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):488–91.

Cohidon C, Wild P, Senn N. Job stress among GPs: associations with practice organisation in 11 high-income countries. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(698):e657–e67.

Schwingshackl A. The fallacy of chasing after work-life balance. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:26.

Kerbl R. Wo ist mein Kinderarzt. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2020;168:474–5.

Frintner MP, Cull WL, Byrne BJ, Freed GL, Katakam SK, Leslie LK, et al. A longitudinal study of pediatricians early in their careers: PLACES. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):370–80.

Starmer AJ, Frintner MP, Freed GL. Work-life balance, burnout, and satisfaction of early career pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20153183. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3183.

Kerbl R. Work-Life-Balance, Zufriedenheit und Burnout bei jungen Pädiatern. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2017;165:98.

Scharer S, Freitag A. Physicians’ exodus: why medical graduates leave Austria or do not work in clinical practice. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2015;127(9–10):323–9.

Ehrich J, Burla L, Carrasco Sanz A, Crushell E, Cullu F, Fruth J, et al. As few pediatricians as possible and as many pediatricians as necessary? J Pediatr. 2018;202:338–9.

Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443–51.

Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–13.

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, Power DV, Eacker A, Harper W, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334–41.

Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):132–49.

West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306(9):952–60.

Zwack J, Schweitzer J. Resilienz im Arztberuf. 2011. http://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/downloads/09-08_Visitenkarte_2011.pdf;. Accessed 12 Feb 2021.

Harper BD, Nganga W, Armstrong R, Forsyth KD, Ham HP, Keenan WJ, Russ CM. Where are the paediatricians? An international survey to understand the global paediatric workforce. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000397.

Zepp F, Krägeloh-Mann I. Perspektiven der ambulanten pädiatrischen Versorgung. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2018;166:101–3.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all pediatricians who participated in this survey. We also thank Gudrun Pregartner (Institute for Medical Informatics, Statistics and Documentation, Medical University of Graz) for statistical advice.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RK designed the study, contributed to writing the manuscript and revised the manuscript. DK designed the study and revised the manuscript. DSK performed statistical analysis, contributed to writing the manuscript and revised the manuscript. TZ contributed to writing the manuscript and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

D.S. Kohlfürst, T. Zöggeler, D. Karall and R. Kerbl declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Austrian Society of Paediatrics. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Availability of data

Data available on request from authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kohlfürst, D.S., Zöggeler, T., Karall, D. et al. Workload and job satisfaction among Austrian pediatricians: gender and generational aspects. Wien Klin Wochenschr 134, 516–521 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-022-02050-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-022-02050-x