Summary

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic degenerative disease of multiple joints with a rising prevalence. Pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) therapy may provide a cost-effective, noninvasive, and safe therapeutic modality with growing popularity and use in physical medicine and rehabilitation. The purpose of this study was to synthesize the current knowledge on the use of PEMF in OA.

Methods

A systematic review of systematic reviews was performed. The PubMed, Embase, PEDro and Web of Science databases were searched based on a predetermined protocol.

Results

Overall, 69 studies were identified. After removing the duplicates and then screening title, abstract and full text, 10 studies were included in the final analysis. All studies focused on knee OA, and four studies also reported on cervical, two on hand, and one on ankle OA. In terms of the level of evidence and bias, most studies were of low or medium quality. Most concurrence was observed for pain reduction, with other endpoints such as stiffness or physical function showing a greater variability in outcomes.

Conclusion

The PEMF therapy appears to be effective in the short term to relieve pain and improve function in patients with OA. The existing studies used very heterogeneous treatment schemes, mostly with low sample sizes and suboptimal study designs, from which no sufficient proof of efficacy can be derived. A catalogue of measures to improve the quality of future studies has been drawn up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative disease that affects one or more joints and is associated with inflammatory processes in the synovium, loss of cartilage, and alterations of bone structure. An OA can manifest clinically as pain, swelling, deformity, instability, or impaired function in the affected joints. Typical localizations include knee, hip, hand, as well as lumbar and cervical joints [1]. The prevalence of OA is expected to increase in the coming decades due to the aging general population. Globally, the prevalence of knee OA in people aged 15 years and over is around 16%, while the prevalence in people over 40 years of age is much higher at around 22.9%. The pooled global incidence is 203 per 10,000 person-years in those over the age of 20 years, with females and people with obesity being more likely to be affected. Knee OA is the most prevalent form of OA accounting for 75% of the worldwide OA burden [2]. In addition to invasive, operative interventions, a multitude of conservative treatment options are available, especially in the field of physical medicine, including but not limited to physiotherapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), acupuncture, local heat and cold application, as well as pharmacological analgesia, e.g. with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) [3].

Pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) therapy is an emerging modality for the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders with a wide range of indications for use and has been approved by the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [4]. The PEMF involves time-varying magnetic fields that are generated by strong electrical currents passing through a coil. The frequency, intensity, and shape (i.e. shape of intensity change over time) of these magnetic pulses can be determined and manipulated by physicians [5]. Some of the key advantages of PEMF are the high tolerability due to low side effects, its non-invasive nature and the relatively simple therapeutic applicability. Regarding clinical use, PEMF can be effective in relieving pain and improving functionality in patients with OA, as well as accelerating wound healing, reducing inflammation and treating soft tissue injuries [6]. Although several randomized controlled trials (RCT) have been conducted over the past few decades, there is no consensus or guidelines to help physicians tailor the treatment regimen to their patients, particularly in terms of duration, frequency, and intensity of PEMF therapy sessions.

The evidence for the use of PEMF in patients diagnosed with OA is sparse because the quality, amount, and conclusions of RCTs, as well as systematic reviews do not show conclusive results or the conclusions are based on low level clinical evidence. The aim of the present paper is to provide an overview of application modalities and of the effectiveness of PEMF therapy in patients with OA, to summarize the current state of knowledge and to provide a catalogue of measures to improve the quality of future studies.

Methods

This systematic review of systematic reviews was conducted based on a preapproved protocol and on the guidelines recommended by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [7]. The review protocol was not registered.

Search strategy

The databases PubMed, EMBASE, PEDro, and Web of Science were searched from inception up to 1 July 2021, using a combination of the following terms: “magnetic* field* therap*”, “puls* electromagnetic* field* therap*”, “low* field* magnetic* stimulation*”, “*PEMF”, “*LFMS”, and “osteoarthrit*”, with filters set to only include systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the studies included in this analysis followed the PICO (population, intervention, control, and outcomes) model:

-

Population: patients with OA of one or multiple joints who underwent PEMF therapy alone or in combination with other therapeutic modalities.

-

Intervention: studies reporting on the influence of PEMF alone or in combination with other modalities.

-

Outcome: studies reporting on the influence of PEMF or any outcome associated with OA.

-

Study designs including systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded for the following reasons:

-

Design other than a systematic review (narrative reviews).

-

Unavailability of data to be extracted, in this case the corresponding author has been contacted. If no information was available from the corresponding author, the study was excluded.

-

Systematic reviews of observational studies.

-

Systematic reviews of non-clinical studies or animal model studies.

-

Full text articles in a language other than English or German.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers (LM and BW) conducted a title and subsequent abstract screening. If the inclusion criteria were met, or if further information was needed to determine whether the inclusion criteria were fulfilled, studies were evaluated in full text form. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, through a third independent reviewer (RC).

Data extraction and critical appraisal

An extraction plan was created based on the consensus of the authors. Data were tabulated and a narrative synthesis was carried out. The following categories are included in Table 1: name of the first author and year of publication; databases; number and type of studies included; participants: sex, mean age, diagnosis, description and duration of the intervention; control condition; anatomical site of PEMF application; quality assessment tool and its outcomes; outcomes and outcome measures; general conclusion and limitations.

Results

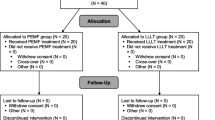

Our systematic review includes 10 systematic reviews that focus on the effect of PEMF on a variety of outcomes in patients with OA, as presented in Table 1. An overview of the literature search and selection process are presented in Fig. 1.

In terms of localization, all systematic reviews include results on knee OA [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], with four reviews additionally including cervical spine [8, 11, 13, 17], two studies reporting on hand OA [8, 11], and one on ankle OA [8]. All included reviews report on the outcomes of individual studies in adults, with a mean age range between 25 and 73 years.

All included systematic reviews reported outcomes on disability or physical function and used the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) [18] as a measurement for physical function or disability. One study additionally reports on activities of daily living. Out of 10 studies, 5 report positive outcomes associated with the application of PEMF in patients with OA [8,9,10,11, 17] and 1 study reports no statistically significant effect of PEMF ([14]; Table 1).

Pain was assessed as an outcome in all of the systematic reviews, with all reviews reporting results of the visual analogue scale and one not reporting which scale was used. In total, five studies report that PEMF had significant effects on pain reduction in patients with OA [8, 9, 11, 15, 17].

Joint stiffness and quality of life were assessed in two reviews reported here [8, 14]. Joint stiffness was assessed using the WOMAC stiffness subscale and quality of life using the SF-36 and EuroQol scales [8, 11]. Overall, reviews report no positive effects on quality of life in patients using PEMF and only one review found significant improvements in joint stiffness [8].

Treatment protocols were very heterogeneous. One review limited the devices studied to full-body mats [12]. The PEMF field intensity varied between 3.4 mcT [9, 13, 14] and 105 mT [8,9,10, 13, 17], with most of the studies being carried out in the millitesla range. Several studies used other units to state magnetic flux density such as Gauss, V/cm or V/m. Treatment frequencies ranged from 0.1 Hz [8, 13] to 27 MHz [14]. Two trials did not provide any information on the field intensity and frequency that was applied [11, 16]. Waveform, if indicated, again was quite different in the respective trials.

Regarding the duration of the intervention, treatments were applied for 6 min [8] to 12 h a day [8, 9, 11], daily [10] to three times a week [10] and over a time period of ten [8] to 45 [9] days.

Discussion

Since previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs often reported contradicting evidence regarding the effectiveness of PEMF in patients with OA, we aimed to provide a comprehensive literature synthesis through a systematic review of systematic reviews in order to gain more insight into the current state of research. Overall, our results show that there is some degree of congruency between studies in the effectiveness of this type of therapy in terms of physical functioning or reduction of disability and pain; however, the discrepancies on the reported outcomes on effectiveness among studies are large and do not allow unequivocal conclusions on the effectiveness of PEMF. The main results and characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Previous studies [11, 16] have reported conflicting results on physical function outcomes; however, the majority of the systematic reviews included in our review suggest a positive effect of PEMF. Some studies have reported the potential mechanisms by which PEMF can relieve pain, emphasizing its role in diminishing proinflammatory cytokines, as well as increasing chondrocyte proliferation and extracellular matrix production. Reducing pain may also be one of the reasons for improvement in physical functioning and reducing the level of disability. When comparing studies and interpreting the results, the specific physical parameters of electromagnetic devices must be taken into account [19]. Necessary details that characterize an electromagnetic device, such as the type of the field, the intensity of the induction, frequency, rise and decline of the pulse rate, pulse shape and vector or exposure time, are rare information and vary between different treatment protocols. Therefore, comparisons between existing studies and qualified ratings are often difficult [19]. This was confirmed through the results of our analysis. Although most studies focused on knee localization and used the WOMAC scale, the differences between intervention protocols (duration, intensity, and frequencies of the magnetic field) preclude the possibilities of further meaningful comparisons. Given these differences, a meta-analysis was not possible either. Special features of the various devices only allow a comparison with respect to comparable physical parameters [19].

Moreover, there are few studies using high intensity magnetic fields that are most likely to produce a physiological response.

There are no guidelines or a clear professional consensus on the use of PEMF in the treatment of OA. Reporting the duration of the exposure to the electromagnetic field is particularly important, as a recent study on mesenchymal stem cell differentiation pointed out that the expression of chondrogenic markers was greatest with treatments lasting between 5 and 20 min [20]. There is evidence to suggest that PEMF can induce cellular signaling transduction within 5–10 min, while signaling is largely depleted after 30 min [21,22,23].

While most studies reported outcomes on knee OA, those that reported on cervical OA mostly found minor effects for this patient population. This may be due to the neural and vascular structures that may compress the cervical canal and lead to a number of symptoms including numbness of the limbs, falls, and pain in the nerve root of the upper limb [24, 25]. There is no evidence that PEMF can reduce the formation of osteophytes, which often lead to compression of the nerve root and resulting pain and loss of function [26, 27].

The limitations of our systematic review are mostly related to the individual limitations of the included reviews, which are predominantly due to the small number of participants in the included studies and the high heterogeneity of the interventions and outcomes. The main limitation of this systematic review of systematic reviews is the small number of studies that could be included. Moreover, we only included studies that were published in English and German.

Conclusion and implications for future research

The results of our review suggest that the use of PEMF is a safe and noninvasive therapy option for patients with OA that can lead to improvements in pain and physical function.

Future studies should aim to:

-

Further improve the quality of future studies, for example by aiming for a more meticulous study design and by ensuring proper blinding and randomization in larger and better defined samples, in order to further improve the quality and level of evidence for the use of PEMF in patients with OA.

-

Conduct future trials with homogeneous outcome assessment (to enable future meta-analysis).

-

Achieve an international consensus on the uniform reporting of the magnetic flux density of the applied electromagnetic fields, such as microtesla/millitesla or Gauss, in order to be able to better compare study protocols.

-

Standardize additional therapeutic modalities, such as physiotherapy, hyperthermia, TENS, or ultrasound if these modalities are used in conjunction with PEMF to enable meaningful comparisons between groups.

-

Provide sufficient information on the treatment protocol (e.g. frequency, intensity, waveforms, treatment duration) and on therapy adherence.

-

Evaluate the optimal type, frequency, intensity and duration of PEMF interventions in order to develop standardized protocols. It can make sense to homogenize interventions according to the particular physical parameters of the applied electromagnetic fields as well as according to the duration of treatment and treatment indication.

-

Evaluate the effect of PEMF on osteoarthritic conditions other than the knee, for example in patients with coxarthrosis

-

Continue to evaluate the safety of PEMF interventions (especially when high-intensity protocols are used over a long period of time)

-

Evaluate a shorter duration of the electromagnetic fields in RCTs, as there is limited evidence that they affect cellular changes. Similarly, evaluate protocols using high-intensity magnetic fields in the millitesla range that allow sufficient penetration of body tissues as they are likely to produce a stronger physiological response.

References

Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, Bannwarth B, Bijlsma JW, Dieppe P, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: Report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(12):1145–55.

Cui A, Li H, Wang D, Zhong J, Chen Y, Lu H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29–30:100587.

Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden NK, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(4):476–99.

Dolkart O, Kazum E, Rosenthal Y, Sher O, Morag G, Yakobson E, et al. Effects of focused continuous pulsed electromagnetic field therapy on early tendon-to-bone healing. Bone Joint Res. 2021;10(5):298–306.

Grodzinsky AJ. Fields, forces, and flows in biological systems. : Routledge, Taylor & Francis; 2011.

Raji AR, Bowden RE. Effects of high peak pulsed electromagnetic fields on degeneration and regeneration of the common peroneal nerve in rate. Lancet. 1982;2(8295):444–5.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003583.

Yang X, He H, Ye W, Perry TA, He C. Effects of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy on pain, stiffness, physical function, and quality of life in patients with osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Phys Ther. 2020;100(7):1118–31.

Vigano M, Perucca Orfei C, Ragni E, Colombini A, de Girolamo L. Pain and functional scores in patients affected by knee OA after treatment with pulsed electromagnetic and magnetic fields: a meta-analysis. Cartilage. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1947603520931168

Chen L, Duan X, Xing F, Liu G, Gong M, Li L, et al. Effects of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy on pain, stiffness and physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rehabil Med. 2019;51(11):821–7.

Wu Z, Ding X, Lei G, Zeng C, Wei J, Li J, et al. Efficacy and safety of the pulsed electromagnetic field in osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(12):e22879.

We RS, Koog YH, Jeong KI, Wi H. Effects of pulsed electromagnetic field on knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology. 2013;52(5):815–24.

Hug K, Roosli M. Therapeutic effects of whole-body devices applying pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF): a systematic literature review. Bioelectromagnetics. 2012;33(2):95–105.

Vavken P, Arrich F, Schuhfried O, Dorotka R. Effectiveness of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy in the management of osteoarthritis of the knee: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(6):406–11.

Bjordal JM, Johnson MI, Lopes-Martins RA, Bogen B, Chow R, Ljunggren AE. Short-term efficacy of physical interventions in osteoarthritic knee pain. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:51.

McCarthy CJ, Callaghan MJ, Oldham JA. Pulsed electromagnetic energy treatment offers no clinical benefit in reducing the pain of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:51.

Li S, Yu B, Zhou D, He C, Zhuo Q, Hulme JM. Electromagnetic fields for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003523.pub2.

Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–40.

Bachl N, Ruoff G, Wessner B, Tschan H. Electromagnetic interventions in musculoskeletal disorders. Clin Sports Med. 2008;27(1):87–105.

Parate D, Franco-Obregon A, Frohlich J, Beyer C, Abbas AA, Kamarul T, et al. Enhancement of mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis with short-term low intensity pulsed electromagnetic fields. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9421.

Dibirdik I, Kristupaitis D, Kurosaki T, Tuel-Ahlgren L, Chu A, Pond D, et al. Stimulation of Src family protein-tyrosine kinases as a proximal and mandatory step for SYK kinase-dependent phospholipase Cgamma2 activation in lymphoma B cells exposed to low energy electromagnetic fields. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(7):4035–9.

Uckun FM, Kurosaki T, Jin J, Jun X, Morgan A, Takata M, et al. Exposure of B‑lineage lymphoid cells to low energy electromagnetic fields stimulates Lyn kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(46):27666–70.

Kristupaitis D, Dibirdik I, Vassilev A, Mahajan S, Kurosaki T, Chu A, et al. Electromagnetic field-induced stimulation of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(20):12397–401.

Valat JP, Lioret E. Cervical spine osteoarthritis. Rev Prat. 1996;46(18):2206–11.

Wilder FV, Fahlman L, Donnelly R. Radiographic cervical spine osteoarthritis progression rates: a longitudinal assessment. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31(1):45–8.

Ciombor DM, Aaron RK, Wang S, Simon B. Modification of osteoarthritis by pulsed electromagnetic field—a morphological study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11(6):455–62.

Chang CH, Loo ST, Liu HL, Fang HW, Lin HY. Can low frequency electromagnetic field help cartilage tissue engineering? J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;92(3):843–51.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank OR Mag. Margarete Steiner for the linguistic review of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

L. Markovic, B. Wagner and R. Crevenna declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Markovic, L., Wagner, B. & Crevenna, R. Effects of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy on outcomes associated with osteoarthritis. Wien Klin Wochenschr 134, 425–433 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-022-02020-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-022-02020-3