Abstract

Recent developments in food industries have attracted both academic and industrial practitioners. Shrimp as a well-known, rich, and sought-after seafood, is generally obtained from either marine environments or aquaculture. Central prominence of Shrimp Supply Chain (SSC) is brought about by numerous factors such as high demand, market price, and diverse fisheries or aquaculture locations. In this respect, this paper considers SSC as a set of distribution centers, wholesalers, shrimp processing factories, markets, shrimp waste powder factory, and shrimp waste powder market. Subsequently, a mathematical model is proposed for the SSC, whose aim is to minimize the total cost through the supply chain. The SSC model is NP-hard and is not able to solve large-size problems. Therefore, three well-known metaheuristics accompanied by two hybrid ones are exerted. Moreover, a real-world application with 15 test problems are established to validate the model. Finally, the results confirm that the SSC model and the solution methods are effective and useful to achieve cost savings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the past two decades, a great deal of attention is devoted to varied types and approaches in Supply Chains to reach a more suitable solution to create competitive advantages for companies, governments, and parties. According to the literature, the supply chain is stated as series of facilities that provide the final products (Hajiaghaei-Keshteli and Sajadifar 2010; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli et al 2011). Moreover, the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) defines the Supply Chain Management (SCM) as: “SCM encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing and procurement, conversion, and all logistic management activities. Significantly, it includes coordination and collaboration with channel partners as well, which can be suppliers, intermediaries, third-party service providers, and customers. In essence, supply chain management integrates supply and demand management within and across companies” (Hanne and Dornberger 2017).

In today's world, one of the leading sectors in developed and developing countries is food industries. Food production and distribution have become enough efficient in various aspects to satisfy the growing demands (Sharma et al. 2018). The Food Supply Chain (FSC) is resemblance to any other supply chain, since it made up of several stages (production, handling and storage, processing and packaging, distribution, and consumption). Final goods move along the FSC from the producers to reach consumers through pre- and post-production actions, and under quality and time-conscious work (Govindan et al. 2017; Wunderlich and Martinez 2018). However, it can be separated in many ways, since poorly timed distribution in FSC makes perishable products unusable. It holds, thus, a prominent situation in the global marketplace and has impacts on society and also the economy of countries (Govindan et al. 2017).

Seafood Supply Chain (SFSC) can be classified as a special FSC, that needs momentous consideration. Health benefits of seafood are hidden to no one. Indeed, scientists and organizations believe that seafood teems with substantial nutritional values and assures food security due to the fact that over a third of global population benefit from its protein sources. Furthermore, it is predicted that fisheries and aquaculture are taken into account as prominent protein sources by 2050 as the population increases (Tabbakh and Freeland-Graves 2016; Schiller et al. 2018).

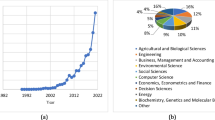

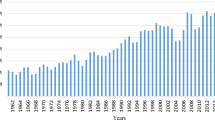

Among seafoods, shrimps are a main source of protein and have low hazardous saturated fat and energy, making them a healthful preference as well as a desirable food around the world. In many developing countries, shrimps are served as a traditional meal and as a luxurious food in developed countries (Alam 2016). Over the past years, food and agricultural organization (FAO)Footnote 1 statistics show that the consumption of shrimp in developed countries like China, the United States, and the United Kingdom is sharply increased, whereas in developing countries such as Iran, this amount is less than a kilogram per capita per year (See: Fig. 1).

Iran has a prodigious potential of shrimp production in its both freshwater and marine resources, which drives from 1800 km long coastline of the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman and also appropriate condition for the fishery on this coastline. More than 2000 shrimp species are identified worldwide, five of which are caught and aquacultured in Iran (See: Fig. 2) (Harlioglu and Farhadi 2016; Schiller et al. 2018).

Shrimps species in Iran [FAO Aquatic Species Information (http://www.fao.org/fishery/collection/cultured-species/en)]

Statistics indicate that 82% of the total global production of shrimp belongs to the Asian countries such as China, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, India, and Bangladesh. Moreover, Ecuador, Peru, Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala, Brazil, Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Belize have a 16% portion and the rest is owned by Saudi Arabia, Madagascar, and Australia (Alam 2016). As FAO fishery statistics show, in 2016, the total global production of shrimp is approximately 8,671,358 tons with 59.74% of aquaculture production and 40.26% of marine capture. Shrimp is a crucial component of the coastal fisheries resources in Iran, and FAO statistics illustrate that shrimp production between 2003 and 2016 has distinctly been grown and shrimp aquaculture has exceeded marine harvests. For example shrimp culture production approaches, in 2014, 22,500 tons (See: Figs. 3, 4).

Supply Chain Network Design (SCND) facilitates making strategic decisions and plays a crucial role in the supply chain performance. Moreover, its competitive benefits affect the operational and tactical levels of the supply chain over the time (Fathollahi-Fard et al. 2017). Nowadays, the economic and environmental concerns arising from the growing demand for shrimp has led to a widespread discussion regarding the performance within the shrimp supply (Lin and Wu 2016). Shrimp, like any other fish product, is perishable food. Hence, several important factors have an indispensable influence on shrimp supply network. Quality of product in distribution, speed, and efficiency in the design of supply network, and finally time delivery and maintenance of cold chain result in the commercial success of the supply chain network (Buritica et al. 2017). Consequently, designing and optimizing the SSC network can help governments, investors, and active parties to satisfy market demands, and to overcome obstacles in the supply chain, and in general can boost performance of the whole chain.

This study designs a mathematical modeling and optimization structure that focus on the SSC network. To the best of our knowledge, there is no prior study involving mathematical modeling for SSC network design. The main goal of the SSC model is to minimize the total cost. Moreover, since the SSC model is characterized by the hard complexity in solving large-scale problems, three recognized metaheuristic algorithms and two hybrid heuristics are conducted to address this issue and to analyze the model. Furthermore, to achieve better performance of these algorithms, the corresponding parameters are tuned by using the Taguchi method.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 entails the related literature review on FSC and SFSC. Our SSC mathematical model is proposed and formulated in Sect. 3. The solution methods and computational results are reported in Sect. 4 and Sect. 5, respectively. Finally, conclusions and suggestions for future works are addressed in Sect. 6.

2 Literature

This section is dedicated to the literature review on FSC and recent pertinent works on SFSC.

2.1 Food supply chain (FSC)

Mostly, food can be divided into two main categories: perishable food (e.g. fruits, vegetables, fishery, aquaculture products, meats, etc.) and non-perishable (e.g. canned, pickled, dehydrate, dried products). Recently, several studies investigated perishable food supply chain for fresh fruits (Cheraghalipour et al. 2018; Soto-Silva et al. 2016), agricultural (Borodin et al. 2016), and dairy (Sel et al. 2015) come along with different components of the supply chain such as inventory, resources location-allocation, planning and scheduling, production, and distribution (Musavi and Bozorgi-Amiri 2017; Govindan et al. 2014; Attanasio et al. 2007; Kaasgari et al. 2017; Dai et al. 2018; Triki 2016; Wu et al. 2018).

One of the first studies on perishable food supply chain was conducted by Stoecker et al. (1985). They used linear integer programming for maximizing the profit and for planning the farm’s crop, livestock, and labor decisions. Miller et al. (1997) provided a simple and a fuzzified linear programs to produce scheduling of fresh tomato packinghouse, then, they compared the costs obtained by each model. Ten Bergeet al. (2000) proposed an explorative model at the whole farm level that effectively integrates component knowledge at a crop or animal level. Then, case studies in dairy farming, flower bulb industry, and arable farming were provided. A mathematical model was presented by Caixeta-Filho (2006) who developed a linear optimization model with chemical, biologic, and logistic constraints for quality of harvested Brazilian’s oranges. Ferrer et al. (2008) recommended a mixed-integer linear programming model containing harvest scheduling, labor allocation, and routing decisions on wine grape harvesting operations by considering both operational costs and grape quality. Arnaout and Maatouk (2010) focused on a vineyard harvesting problem in developing countries to improve wine quality and reduce the operational costs. Additionally, they utilized heuristics for better assigning of harvesting days to different grape blocks and validated the proposed model by solving several numerical examples. Their results showed that their model is prominently able to reduce harvesting costs.

With the aim of maximizing revenues under production and distribution decisions, an operational model was suggested by Ahumada and Villalobos (2011). Tan and Çömden (2012) proposed a planning model to handle the random supply of annual fruits and vegetables from farms and random demands of the retailers, which are results of the uncertainty of harvest time, and uncertainty of weekly demand, respectively. A simulation model for perishable fruit and vegetables supply chain was presented by Teimoury et al. (2013) to investigate behaviors and relationships of supply chain and supply, demand and price interactions. Agustina et al. (2014) studied a mixed-integer linear model of vehicle scheduling and routing at a cross-docking center for perishable food supply chains to minimize earliness, tardiness, inventory holding, and transportation cost. A planning model for apples orchards was proposed by González-Araya et al. (2015) to minimize labor costs, equipment use, loss of fruit quality, and also satisfying packing plants demand. The implementation of this model on three orchards in Chile showed a 16% decrease in the labor costs and loss of income.

Rocco and Morabito (2016) suggested a production and logistics planning linear model for the Brazilian tomato processing industry, which includes tactical planning decisions like the size of tomato area, selection of tomato types, transporting harvests, and so on. Three optimization models for purchasing, transporting, and storing fresh produce were studied by Soto-Silva et al. (2017) to ensure an annual supply of fresh apple. An average of 8% savings in the real costs of purchasing, storing, and transporting arisen from conducting a real case study in apple dehydration in the Maule region of Chile has been achieved. Cheraghalipour et al. (2018) provided a citrus closed-loop supply chain model to minimize costs and maximize responsiveness to customers' demand. One of the most recent food supply chain model was introduced by Ma et al. (2019). They focused on the three-echelon supply chain for seasonal fresh products consisting of one supplier, third-party logistics service providers, and one retailer.

2.2 Recent related works on seafood supply chain (SFSC)

During the last few decades, only a limited number of researchers and academics have studied SFSC in miscellaneous ways. In a preliminary study of SFSC problems, Forsberg (1996) pointed out a multi-period linear programming approach to the production-planning of fish farms. In addition, Forsberg (1999) developed a multi-period linear programming model for fish growth that optimizes the harvest. Sanders et al. (2003) suggested a production model of white sturgeon caviar and meat for various management conditions. Using the network-flow approach, Yu et al. (2009) implemented a nonlinear mathematical model of partial harvesting. Cisternas et al. (2013) designed an integer programming model to improve resource usage, planning, and economic evaluation of grow-out centers. The results obtained from implementing this model in one of the Chile's largest salmon farmers showed a 18% reduction in net maintenance cost together with several qualitative benefits. Bravo et al. (2013) employed mixed integer programming to propose two models for the production planning in salmon farming suffering from a range of biological, economic, and health-related constraints. Bakhrankova et al. (2014) developed a stochastic production-planning model to overcome raw material supply and product market price uncertainties.

As can be noticed from the recent literature, SFSC has been considered in different manners and for various products. Real-world issues and case-based methods is the main factor to design an industrial problem for SSC networks. In our case, we formulated the SSC network according to both the nature and characteristics of the product and due to its importance in Iran and even in today’s food world industry. Developing countries like Iran have incredible capabilities for producing especial seafood like shrimps. There is an extraordinary domestic and oversea market demand for shrimp which can ensure a proper income. So, designing a SSC can be a good start and a preliminary preparation to accomplish this mission. The accurate analysis reported in Table 1 determines the gaps that highlight the significance of this paper. The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

-

This study presented a seven-level MILP supply chain network for shrimp product including marine fishery and aquaculture product resources, distributors, wholesalers, factories, markets (customers), shrimp waste powder factories and poultry and livestock food market.

-

For the first time, the proposed network considered potential factories which use the collected waste of shrimp products as input for their process.

-

In this study, the cost minimization of the network is considered while satisfying the demand of shrimp products and in the same time supplying the demands of poultry and livestock food market.

-

The above review has shown that all previous related works have focused either on marine or aquaculture products; however our proposed model took both the products into account with interesting industrial sights.

-

The literature review has emphasized that most of the supply chain and logistics studies were based on NP-hard models (Jo et al. 2007; Zheng et al. 2013; Deng et al. 2017). Hence, metaheuristic algorithms are the compulsory and the best way to solve large-scale networks (Rocco and Morabito 2020; Wang et al. 2013). Therefore, this research not only takes advantages of classic and modern metaheuristics but also develops two hybrid metaheuristics to solve the suggested NP-hard problem.

This paper addresses a new model to help the managers of shrimp production industries in designing an optimal supply chain network for shrimp products. It also undertakes wastes generated in two main levels of network i.e. wholesalers and shrimp factories. The decisions to be taken within this study consist of:

-

How many and which distribution points, wholesalers, shrimp factories, and shrimp waste powder factories should be selected and established?

-

How much shrimp products and shrimp waste powder should be transported within the network?

-

How do shrimp production and shrimp waste powder optimally flow in the network?

We believe that the mangers can extensively benefit from the suggested mathematical model and its results to make strategic decisions regarding the quality of shrimp flow in the supply network while minimizing the total cost. Additionally, since numerous countries do not have yet the technology to convert shrimp waste to poultry and livestock food, this study can give guidelines to the mangers and governors on how to invest their resources to set up a shrimp waste powder factories in highly potential areas.

3 Proposed model

3.1 Problem description

The present SSC network embodies producers (shrimp fishers and farmers), distribution centers, wholesalers, processing centers (factories), shrimp waste powder factories, poultry and livestock food market, and customers. As can be observed in Fig. 5, captured or aquacultured shrimps are shipped in this network from the producing locations (fishery locations and aquacultures) to the distribution centers. The distribution centers, depending on their capacities, send shrimps to the wholesaler and factories. Furthermore, factories, after peeling, packing or canning, and freezing should transport finished goods to the final customers. Finally, shrimp wastes collected from both wholesalers and factories are shipped to shrimp waste powder factories. These factories make poultry and livestock food in addition to the required nutrients for shrimp farming.

3.2 Assumptions

The following real assumptions are set in the proposed SSC network:

-

The SSC model is a single-period, single-product mixed integer linear programming model.

-

The locations of the fisheries, aquacultures, and customers are considered fixed. On the other hand, the distribution centers, wholesalers, factories, and markets are assumed as potential locations.

-

Market demands must be satisfied.

-

It is supposed that there is shrimp waste and also there is demand for the shrimp powder.

-

Shrimp products are transported and preserved in cold containers.

3.3 Model notations

The indices, parameters, and decision variables for the mathematical model are presented as follows:

Indices | |

i = 1,2,…,I | The production location (shrimp fisher) |

i' = 1,2,…,I' | The production location (shrimp farm) |

j = 1,2,…,J | The potential point of the distribution center |

k = 1,2,…,K | The potential location for the wholesaler |

l = 1,2,…,L | The potential location for the factory |

m = 1,2,…,M | The customer index |

n = 1,2,…,N | The potential site for shrimp waste powder factory |

p = 1,2,…,P | The poultry and livestock food market |

Parameters | |

\({f}_{l}\) | Fixed cost of opening factory l |

\({f{^{\prime}}}_{n}\) | Fixed cost of opening shrimp waste powder factory n |

\({Cx}_{ij}\) | Transport cost per unit of product from shrimp fishers i to distribution center j |

\({Cy}_{i{^{\prime}}j}\) | Transport cost per unit of product from shrimp farmers i' to distribution center j |

\({Cu}_{jk}\) | Transport cost per unit of product from distribution center j to wholesaler k |

\({Ca}_{jl}\) | Transport cost per unit of product from distribution center j to factories l |

\({Cb}_{km}\) | Transport cost per unit of product from wholesaler k to customer m |

\({Cd}_{lm}\) | Transport cost per unit of product from factory l to customer m |

\({Cf}_{kn}\) | Transport cost per unit of shrimp waste from wholesaler k to shrimp waste powder factory n |

\({Cf{^{\prime}}}_{ln}\) | Transport cost per unit of shrimp waste from factory l to shrimp waste powder factory n |

\({Cl}_{np}\) | Transport cost per unit of shrimp waste powder from factory n to market p |

\({\lambda }_{i}\) | Production capacity of shrimp fisher i |

\({\lambda {^{\prime}}}_{i{^{\prime}}}\) | Production capacity of shrimp farmer i' |

\({\lambda d}_{j}\) | Holding capacity at distribution center j |

\({\lambda f}_{l}\) | Production capacity of factory l |

\({\lambda w}_{k}\) | Holding capacity at wholesaler k |

\({\lambda s}_{n}\) | Production capacity of shrimp waste powder factory n |

\({\alpha }_{k}\) | Shrimp waste rate by wholesaler k |

\({\beta }_{l}\) | Shrimp production rate by factory l |

\({\xi }_{n}\) | Shrimp waste powder production rate by factory n |

\({Db}_{m}\) | Shrimp product demand by customer m |

\({Dp}_{p}\) | Shrimp waste powder demand by poultry and livestock food market p |

Decision variables | |

\({X}_{ij}\) | Quantity of product transported from shrimp fisher \(i\) to distribution center \(j\) |

\({X{^{\prime}}}_{i{^{\prime}}j}\) | Quantity of product transported from shrimp farmer \(i{^{\prime}}\) to distribution center \(j\) |

\({U}_{jk}\) | Quantity of product transported from distribution center \(j\) to wholesaler \(k\) |

\({S}_{jl}\) | Quantity of product transported from distribution center \(j\) to factory \(l\) |

\({W}_{km}\) | Quantity of product transported from wholesaler \(k\) to customer \(m\) |

\({V}_{lm}\) | Quantity of product transported from factory \(l\) to customer \(m\) |

\({R}_{kn}\) | Quantity of waste shrimp transported from wholesaler \(k\) to shrimp waste powder factory \(n\) |

\({G}_{ln}\) | Quantity of waste shrimp transported from factory \(l\) to shrimp waste powder factory \(n\) |

\({B}_{np}\) | Quantity of shrimp waste powder transported from factory \(n\) to market \(p\) |

\({Ih}_{j}\) | Quantity of stored shrimp by distribution center \(j\) |

\({Dis}_{j}\) | Equal to 1 if distribution center \(j\) is opened at the elected location, 0 otherwise |

\({Wh}_{k}\) | Equal to 1 if wholesaler \(k\) is opened at the elected location, 0 otherwise |

\({Fr}_{l}\) | Equal to 1 if factory \(l\) is opened at the elected location, 0 otherwise |

\({Wp}_{n}\) | Equal to 1 if shrimp waste powder factory \(n\) is opened at the elected location, 0 otherwise |

3.4 Shrimp supply chain mathematical model

The schematic view of the SSC network is illustrated in Fig. 6. The proposed mixed integer linear programming model of the SSC problem is formulated as follows:

-

Objective Function

The objective function of the SSC is to minimize the total cost including fixed opening costs and transportation costs by means of Eq. (1).

$$ \begin{aligned} Min~Z = \left[ {\mathop \sum \limits_{{l = 1}}^{L} f_{l} \times Fr_{l} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{n = 1}}^{N} f'_{n} \times Wp_{n} } \right] + \left[ {\mathop \sum \limits_{{i = 1}}^{I} \mathop \sum \limits_{{j = 1}}^{J} Cx_{{ij}} \times X_{{ij}} } \right. \hfill \\ & + \mathop \sum \limits_{{i' = 1}}^{{I'}} \mathop \sum \limits_{{j = 1}}^{J} Cy_{{i'j}} \times X'_{{i'j}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{j = 1}}^{J} \mathop \sum \limits_{{k = 1}}^{K} Cu_{{jk}} \times U_{{jk}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{j = 1}}^{J} \mathop \sum \limits_{{l = 1}}^{L} Ca_{{jl}} \times S_{{jl}} \hfill \\ &+ \mathop \sum \limits_{{k = 1}}^{K} \mathop \sum \limits_{{m = 1}}^{M} Cb_{{km}} \times W_{{km}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{l = 1}}^{L} \mathop \sum \limits_{{m = 1}}^{M} Cd_{{lm}} \times V_{{lm}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{k = 1}}^{K} \mathop \sum \limits_{{n = 1}}^{N} Cf_{{kn}} \times R_{{kn}} \hfill \\ \left. { + \mathop \sum \limits_{{l = 1}}^{L} \mathop \sum \limits_{{n = 1}}^{N} Cf'_{{\ln }} \times G_{{\ln }} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{n = 1}}^{N} \mathop \sum \limits_{{p = 1}}^{P} Cl_{{np}} \times B_{{np}} } \right] \hfill \\ \end{aligned} $$(1) -

Constraint

$$\mathop \sum \limits_{j = 1}^{J} Dis_{j} \ge 1$$(2)

Constraint (2) states that at least one distribution center should be opened. Constraint (3) state that the quantity of products transported from shrimp fishers to distribution centers should be less than or equal to the production capacity of each producer. Similarly, constraint (4) applies to the shrimp farmers case. Constraint (5) indicates that the quantity of products transported from the producers to the distribution centers should be less than or equal to the holding capacity of each distribution center, if it is opened. Constraint (6) implies that the quantity of products transported from the distribution centers to the wholesalers and factories should not exceed the quantity of products transported from the producers to distribution centers. Constraints (7) and (8) determine that at least one wholesaler and one factory should be opened, respectively. Constraint (9) indicates the quantity of products to be transported from the distribution centers to the factories should respect the holding capacity of each factory, if it is opened. Likewise, constraint (10) applies to the wholesaler. Constraint (11) ensures that the quantity of product transported from wholesaler and factories to each customer is less or equal to the demand at customers side. Constraint (12) ensures that products transported from distribution centers to wholesalers minus wasted shrimp product are equal to the amount of product transported from wholesalers to customers. Constraint (13) ensures that shrimp production by factories is equal to the quantity of product transported from factories to customers. Constraint (14) determines that at least one shrimp waste powder factory should be activated. Constraint (15) ensures the respect of the shrimp waste powder factories capacities. Constraint (16) ensures that wasted shrimp product transported from distribution centers to wholesalers is equal to waste products transported from wholesalers to shrimp waste powder factories. Constraint (17) ensures the flow balance of the waste shrimps between factories and shrimp waste powder factories. Constraint (18) establishes the equality between the produced shrimp waste powder and the quantity of product transported to poultry and livestock food market. Constraint (19) guarantees the demand satisfaction of the poultry and livestock food market. Finally, constraints (20) represent the 0/1 restriction on the binary variables and constraints (21) enforce the non-negativity of the continuous decision variables.

The above model results to be a mixed-integer linear model whose size increases quickly with the number of shrimp fishers, farms, distribution centers, wholesalers, shrimp factory, customers, shrimp waste powder factories and poultry and livestock food markets. Consequently, we will suggest in the sequel metaheuristic algorithms to solve real-world instances of SSC problems in a reasonable time.

4 Solution approach

As mentioned earlier, real-world supply chain network problems are complex and result to be NP-hard for large-scale instances (Jo et al. 2007; Zheng et al. 2013; Deng et al. 2017). Using exact methods to solve these problems would be time-consuming and inefficient especially for large-size problems (Rocco and Morabito 2020; Wang et al. 2013). In this study, the Genetic Algorithm (GA), Simulated Annealing (SA) and Keshtel Algorithm (KA) are employed to solve the problems. Moreover, two hybridized algorithms including Hybrid of Genetic Algorithm with Simulating Annealing (HGASA) and Hybrid of Keshtel Algorithm with Simulating Annealing (HKASA) are utilized to find the sub-optimal solution. In the sequel, the encoding and decoding approaches used in the metaheuristic algorithms are explained.

4.1 Encoding and decoding

Among the numerous approaches for encoding solutions in metaheuristics, we use the recent priority-based method (Cheraghalipour et al. 2018). Here, the proposed chromosome for the SSC network and application of the priority-based method for satisfying all the constraints is enlightened using a small-size example. Assume that the numbers of shrimp fishers, shrimp farms, distribution locations, wholesaler, factories, customers, and shrimp waste powder factories, and poultry and livestock food markets are 2, 3, 3, 2, 2, 3, 2, and 2, respectively. The proposed chromosome is a matrix with one row and (i + i' + 2 × j + 3 × k + 3 × l + m + 2 × n + p) columns that can be divided column-wise into five segments. The representation of proposed chromosome is presented in Fig. 7. Each segment in the proposed chromosome is designed according to the network illustrated in Fig. 6.

After generating the chromosome, whose all members are random numbers in the interval of (0,1), all values are transformed into a priority-based matrix. As shown in Fig. 8, Segment 1 states the amount of transported products from shrimp fishers and shrimp farmers (i + i') to the distribution centers (j). As reported in Fig. 9, in Segment 2, products are allocated to wholesalers and shrimp factories (k + l) from the distribution centers (j). According to Figs. 10 and 11, in segment 3, the allocation of products from wholesalers and shrimp factories (k + l) to customers is conducted and segment 4 obtains the allocation of wasted products from wholesalers and shrimp factories (k + l) to shrimp waste powder factories (n). Finally, the allocation of shrimp waste powder products from shrimp waste powder factories (n) to the poultry and livestock food markets is performed in segment 5 (Fig. 12). For more information about the priority-based method, refer to (Cheraghalipour et al. 2018).

4.2 Metaheuristics

During the last years, scholars have used numerous metaheuristic methods to solve NP-hard problems and attain a prominently proper solution. Timesaving, useful for more complex problems, and avoidance of local optimum are the most outstanding advantages of these methods (Van Engeland et al. 2018; Diarrassouba et al. 2019; and Fathollahi-Fard et al. 2020). For example, in order to solve the order acceptance and supply chain scheduling problem, Sarvestani et al. (2019) applied GA and Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS). Yousefi et al. (2018) used GA to tackle the fixed-charge transportation problem. Govindan et al. (2015) designed a sustainable supply chain problem for order allocation and sustainability including stochastic demand and used a multi-objective metaheuristic approach to solve the given problem. This study utilizes the benefits of metaheuristic algorithms and develops three metaheuristic algorithms including GA, SA, KA as well as two hybrid metaheuristics i.e. HGASA and HKASA to solve the SSC network design. In the following sections, the mentioned algorithms are discussed and the pseudo code of each algorithm is rendered.

4.2.1 Genetic algorithm (GA)

Genetic algorithm (GA) is an outstanding evolutionary algorithm, contributing to solve successfully many applications in different fields. Holland (1992), inspired by the genetic science and natural evolution, developed GA for the first time. GA brings two main operators, including crossover and mutation, into play to execute intensification and diversification in the search process of the algorithm. Additionally, for the proportional selection within the algorithm, we apply the probabilistic selection (Talbi 2009). Our pseudo-code of GA is illustrated in Fig. 13.

4.2.2 Simulated annealing (SA)

The Simulated Annealing (SA) algorithm emerged simultaneously in two different works (Kirkpatrick et al. 1983; Černý 1985). This algorithm is centered on the process of obtaining a crystalline structure in which a slow cycle of cooling and heating (annealing) passes (Deroussi 2016; Talbi 2009). Eskandari-Khanghahi et al. (2018), Torkaman et al. (2018) and Fahimnia et al. (2018) used SA to solve supply chain problems. SA is a single-solution algorithm whereby it takes an initial solution as the best solution in the first place. Therefore, it looks into the vicinity of this solution for the likely best solution. The pseudo code of the SA algorithm is as follows (Fig. 14):

4.2.3 Keshtel algorithm (KA)

Keshtel Algorithm (KA) is a novel metaheuristic algorithm recently used by many researchers to develop numerous studies (Golshahi-Roudbaneh et al. 2017; Fathollahi-Fard et al. 2018a; Cheraghalipour et al. 2018). This algorithm, which is based on the feeding behavior of a dabbling duck, namely Keshtel, is introduced by Hajiaghaei-Keshteli and Aminnayeri (2013). Keshtels habitually search for food in superficial water. Once a Keshtel meets a food source, its neighbors miraculously come close and swirl in a circle way. After the consumption of food, they look for another place containing better food source, and they act in the same way once the food is found. As far as the absence of proper food source in the place, this iterative process continues. Then, each Keshtel disbands and searches different spots in the lake for a food source. Similarly, when one of the Keshtels finds food, its neighbors approach and repeat the same process as above. KA, akin to other population-based metaheuristic algorithms, begins with an initial population, known as Keshtels. Initial Keshtels break up to three categories including N1 entails lucky Keshtels, which are some Keshtels that find the food faster than others do. Worst solutions are gathered as N3 population, and are regenerated randomly in each iteration. After finding better food, a new lucky Keshtel is replaced for each lucky Keshtel; otherwise, the swirling process will be carried on. N2 represents Keshtels that move between N1 and N3 population. Obviously, N1 is responsible for intensification in KA, and N2 and N3 ensure the diversification phase. Figure 15 sketches the pseudo-code of our KA (Fathollahi-Fard and Hajiaghaei-Keshteli 2018a,2018b; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli and Aminnayeri, 2013).

4.3 Hybrid metaheuristics

In recent studies, a great development in nature-based metaheuristics can be seen. The advantages of the different metaheuristic algorithms draw many researchers’ attraction to improve the intensification and diversification phases of the algorithms using various hybrid ones (Hajiaghaei-Keshteli and Fathollahi Fard 2018). In this study, two hybrid algorithms are exercised, including HGASA and HKASA. These two hybrids are combination of GA and KA as two distinct population-based techniques together with SA as a single-solution algorithm. In the following subsections, detailed explanations of HGASA and HKASA are provided.

4.3.1 Hybrid of genetic algorithm and simulating annealing (HGASA)

As mentioned earlier, GA has two operators for intensification and diversification of the algorithm. SA, as an acceptance phase, can be implemented as mutation phases. In this approach, SA creates competition between parents and offsprings in a way that first all parents and offsprings are compared. If offsprings have better fitness value compared to their parents, they are accepted; otherwise, we accept offsprings according to the acceptance criteria in SA algorithm. This procedure helps HGASA to evade from local optimum (Zhu and Weng 2012).

4.3.2 Hybrid of Keshtel algorithm and simulating annealing (HKASA)

As shown in Sect. 4.2.3, KA benefits from two strong operators, namely swirling and moving, for the intensification phase. In such phase of KA, Keshtels in N3 group are replaced by new random Keshtels. Although the randomization step in KA is endorsed by different studies (Golshahi-Roudbaneh et al. 2017; Fathollahi-Fard et al. 2018a; Cheraghalipour et al. 2018), SA is able to improve this procedure in each iteration. Hence, our proposed HKASA approves new random Keshtels either they because they have better fitness than prior ones or if they pass the acceptance criteria of the SA algorithm.

5 Computational results

In the following section, the parameters value for each random test is determined. Taguchi experimental design method is used to tune parameters of the metaheuristics. Eventually, to evaluate the performance of the proposed model, a case study is conducted.

5.1 Data generation

A set of test problems with different dimensions are considered to endorse the proposed model. Here, 15 test problems are designed. Table 2 shows the test problems generated to achieve the purpose of this study. The test problems are indiscriminately defined by using the parameters shown in Table 3. It should be mentioned that the approximated value of each parameter is estimated and extracted on the basis of the Iran Fisheries Organization databanks.

5.2 Parameters tuning

Tuning the parameters in metaheuristics is a crucial phase because it may lead to a wasteful execution of the metaheuristics if the parameters are not set rightfully (Fathollahi-Fard and Hajiaghaei-Keshteli 2018a). Although there are numerous researchers who tested all possible combinations of factors for parameter tuning (Jabbarizadeh et al. 2009; Naderi et al. 2008; Al-Aomarm and Al-Okaily 2006), when the number of factors increase in a problem, their findings are disclosed to be inefficient. Henceforward, for parameters tuning purpose, we use the efficient Taguchi experimental design method, developed by Taguchi (1986). The parameters and their levels for the algorithms have been evolved from (Fathollahi-Fard et al. 2018b). For each factor, three levels are taken into account to design the experiments. In GA and SA, we have four parameters with three levels, and for KA, we take five factors with three levels into account. The hybrid cases, HKASA and HGASA, contain seven factors with three levels, and six factors and three levels, respectively. Thus, L27 is recommended as a proper array for both SA and KA and also L9 for GA.

In this study, we generated, for the sake of validating the proposed model, 15 test problems put into three categories, consisting of small-size, medium-size, and large-size. Hence, the orthogonal array has been run for each test problem using Minitab software. Owing to the size difference of each problem, the Relative Percentage Deviation (RPD) or mean of means is operated to compare the results. The RPD is defined as follows for minimization problems:

where \(Min_{sol}\) is the best solution among all solutions and \(Alg_{sol}\) is the result of algorithm. The mean RPD is computed on the basis of the RPDs from the objective values. Also, the optimal levels for metaheuristic algorithm are summarized in Table 4.

5.3 Applied example

In this section, applied instances are exercised to corroborate the pertinency of the model and solving methodology. To this end, fifteen test problems in different dimension scales are solved with tuned parameters of each metaheuristic (Table 2). Among these examples, the second example is inspired by a small-sized case in southern Khuzestan province situated in southern Iran. Khuzestan province is surrounded by the Persian Gulf and has several rivers such as Arvand river, Karun river, etc. Thus, it has marine access with shrimp production capacity as well as numerous fishery farms which are active in this province. In the real-case example, four shrimp catching location is considered. These four location are Karun river in Ahvaz, Arvand river in Abadan, Bahmanshir river in Abadan, and Musa Bay in Mandar-e-Emam. Five shrimp farms exist in Ahvaz, Abadan, Mahshahr, Shadegan, and Hendijan. Other details on the case study are shown in Fig. 16 as a symbolic scheme for SSC network which contains producers, distribution centers, wholesalers, factories, shrimp waste powder factories, poultry and livestock food market, and customers in Khuzestan province.

At this point, we will attempt to solve the problems by our five the different algorithms, GA, SA, KA, HKASA, and HGASA. Note that the parameters are fixed but the size of test problems alters during the analysis. In fact, when a factory is added to the dimension of the model, all related parameters are selected through Table 3. To assess the performance of the metaheuristic algorithms, four measures including RPD, one-way ANOVA, hitting time, and the computational time of the algorithms are considered, as shown in Table 5 (Fig. 16).

Figures 17, 18 and 19 depict the objective function behavior for various problem sizes. It is obvious that there are slight differences between the values obtained by the different algorithms. Within this, it is clear that in terms of the cost values, SA and HKASA act better than the rest of the algorithms.

The RPD is a reliable criterion that can be defined to evaluate and compare the quality of the solution for the algorithms. Here, RPD is the relative deviation of the outcome of each algorithm from the optimal result among the five implemented approaches. These results for each test size are shown in Fig. 20. In terms of RPD, HKASA shows better performance than all other algorithms for all the three categories. Another avenue to evaluate the performance of the proposed metaheuristic algorithms is using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to account for any statistically significant differences between the RPD of the algorithms. RPD is a response variable and all five metaheuristics algorithms are factors. Two hypotheses are considered for the ANOVA test. The p-value for ANOVA test is equal to zero; therefore, it can be concluded that there are statistically significant differences in the RPDs. For more precise analysis, the means plot and the least significant difference (LSD) intervals at 95% confidence level are presented in Figs. 21, 22 and 23 for small-size, medium size, and large size problems, respectively. In small-size problems, there is negligible difference between the performance of SA, KA, and HKASA (Fig. 21). As shown in Fig. 22, in medium-size cases, KA outperformes all other algorithms. Finally, the best performance among all algorithms belongs to HKASA for large-size problems (Fig. 23).

Hitting time is a tool used to investigate the speed of algorithms in different problem sizes. It is defined as the first time at which each algorithm obtains the best solution. Figure 24 demonstrates the hitting time comparison for the proposed algorithms. We can conclude that the increment of the hitting time coincides with the augmentation of problems sizes. Apparently, the growth rate of hitting time in KA and HKASA is more than that of GA, SA, and HGASA.

The last measure used to check the performance of our algorithms is the computation time. Figure 25 displays the information related to the computational time for all algorithms. Not surprisingly, the SA obviously has the least computational time and after followed by the GA, HGASA, KA, and HKASA.

5.4 Sensitivity analyses

In general, Sensitivity analysis is used to show how output variables change based on the variation of input parameters. In mathematical programming terms, sensitivity analysis is a way to explore the effect of changes in the values of parameters on objective function. To shed light on the functional capability of the proposed model and provide a managerial insight, a sensitivity analysis on the major parameters are performed. Since the HKASA demonstrated to be one of the most efficient algorithms with respect to different metrics, it has been applied here for the sensitivity analysis. Also, we selected the large-size experimental instance 14 as a test problem. Thus, we create three scenarios for sensitivity analysis in which we examine the behavior of cost function under the change of capacity parameters, production/waste rate, and demands for each sector.

The first scenario explores the changes in the production capacity of shrimp fisher (\(\lambda_{i}\)), the production capacity of shrimp farmer (\(\lambda ^{\prime}_{i^{\prime}}\)), the holding capacity at distribution center (\(\lambda d_{j}\)), the production capacity of factory (\(\lambda f\)), holding capacity at wholesaler (\(\lambda w_{k}\)), and production capacity of shrimp waste powder factory (\(\lambda s_{n}\)). In this scenario, each parameter varies between 5 to 35 tons and other parameters are kept unaltered. The performance of the objective function with respect to the change of capacity parameters are shown in Table 6 and Fig. 26. As shows Fig. 26 with the increase in the amount of capacity of each sector, the objective function also increases. However, there is significant difference between the effect of factories, distribution centers, and wholesalers on the objective function in comparison with the other factors. So, it can be inferred that the capacity of shrimp production factories, distribution centers, and wholesalers should be determined carefully to avoid risky increase in the cost of the supply chain network.

The second scenario seeks for the effect of changes in shrimp waste rate by the wholesaler (\(\alpha_{k}\)), shrimp production rate by factories (\(\beta_{l}\)), and shrimp waste powder production rate by factories (\(\xi_{n}\)). Here, we consider the decrease in shrimp waste rate by wholesaler, and increase in both shrimp production rate by factories, and shrimp waste powder production. The results of this scenario are presented in Table 7 and Fig. 27. According to Fig. 27, we realize that all considered factors are positively associated with an increase in the objective function value. However, shrimp production rate of factory is reasonably effective rather than the others.

The last scenario investigates the influence of shrimp product demand by customers (\(Db_{m}\)), and shrimp waste powder demand by poultry and livestock food market (\(Dp_{p}\)) on the supply chain network cost. The results of the third scenario are separately calculated for customer’s demands and shrimp waste powder demand and shown in Table 8 and Fig. 28. The results indicate that whenever the demand in both sides vary increasingly, there is advance in optimum objective function value. Additionally, it is derived from Fig. 27 that demands of customers have more significant effect on the overall cost of the supply chain network than the shrimp waste powder demand.

6 Managerial insights

The purpose of this paper was to provide a supply chain network for both shrimp products engendered by marine and aquaculture. The strength of this model consists in the novelty of returning shrimp waste made by wholesalers and shrimp factories as raw material to shrimp waste powder factories. The use of the suggested supply chain network can significantly help in providing the governors and seafood industries managers with guidelines on how to take strategic decisions. Iran has great potential capacity in seafood and aquaculture production such as skilled academic experts, affordable industrial requirement such as facilities, oil and fuel, human resources. Moreover, it has the most substantial advantage of direct access to three marine zones (the Persian Gulf, Gulf of Oman, and the Caspian Sea) and its great capability of establishing aquaculture projects in these locations. According to the statistical evidences, developing countries and specifically Iran, have not yet approached to their satisfactory achievements in seafood industry, especially with respect to shrimp products. Indeed, we believe that countries like Iran should take advantage of its great opportunities and competencies in seafood industry to boost its economy by gaining remarkable profits and avoiding losses of capabilities.

Going in this direction, the model has assumed potential locations for the distribution center, wholesaler, shrimp factories, and shrimp waste powder factory. So, the findings of this model can help investors and governors to get the best location to optimally distribute and transport shrimp products throughout the network. Moreover, shrimp industries can find it advantageous, on the basis of this study, to enrich their business by recycling the shrimp wastes, if they still didn’t implement such technology, with further benefits to the environment.

Another managerial implication of this study is concerned with shrimp factories. The managers of these factories can apply this model to improve their fixed opening and transportation costs and manage production flows and supply chain activities. As a result, the optimized supply chain network design leads to pay the lowest cost and to deliver the highest service level. These two privileges bring competitive advantages over similar supply chains especially in the countries around the Persian gulf. For instance, the managers can fit their production capacities and demand of market with the suggested constraints in the model. Furthermore, the sensitivity analysis on demands and the other data together with the setting parameters can give valuable insights to the supply chain decision-makers. The last but not the least, managers always seek for efficient ways to solve their problems and make decision successfully. This study offered several metaheuristics that can be exploited by the managers of shrimp production industries to solve their specific, or similar variants, of network design.

7 Conclusion and future works

Lately, due to the incessant progress of aquaculture production, international markets, and changes in customers’ desires, seafood business has been astoundingly developed. In many developed and developing countries, seafood constitutes the most critical parts of people’s daily diet. Shrimp products is a desirable seafood among many populations, and it represents a significant amount of food intake in different societies. Shrimp products is either caught from marine environment like seas and rivers, or farmed in aquaculture systems. So, designing a proper supply chain network for shrimp productions can offer many benefits for decision-makers, organizations, factories, or even markets to improve the functionality of supply chain. Thus, this paper introduced a mathematical model for the SSC network to retrieve the desirable goals of optimizing the total cost of whole network while respecting a set of operational restrictions.

The solution the proposed model has been ensured by three renowned metaheuristic algorithms: GA, SA, and KA. Additionally, two hybrid metaheuristic algorithms, including HGASA and HKASA, that embed the advantages of SA algorithm, were proposed. Thereafter, the Taguchi method was used to tune and set the parameters of the algorithms with the aim of achieving their better performance. An applied example with 15 test problems was generated considering the application of the SSC to the Iranian real case, and four measures were used to compare the results of the designated algorithms. Even though the algorithms have shown different behavior with respect to the considered measures, the results show that KA and HKASA had satisfactory performance, over the others, in solving the problem under exam. In additions, the results show the applicability of the suggested SSC network in practice and to the effectiveness of proposed metaheuristics.

Principally, this study presented practical and methodological contributions. From the practical standpoint, this paper proposed a mathematical model for designing a SSC network as sought-after seafood and increasingly thriving market. The capability of the model is used to handle the forward flow of shrimp product from marine catching or aquaculture production to distribution centers then to wholesalers and shrimp factories, and afterward to markets. It also manages the reverse flow of waste product from wholesalers and shrimp factories to shrimp powder factories and to livestock and poultry food markets. The model helps to satisfy both the demands of shrimp products in markets and demand of by-products originated from waste shrimps while it deals with the capacity restriction of the distributors, factories, and particularly shrimp production. Regarding the methodological viewpoint, this study developed a combination of efficient classic, modern, and hybrid metaheuristics to increase the quality of problem solving. The sensitivity analyses are inspired from the most related and recent studies such as Cheraghalipour et al. (2019) and Abdi et al. (2019).

There could be diverse extension on the presented work for future studies. From mathematical modeling view, the model can involve the multi-objective aspect by adding a product quality function by considering shelf-life of shrimp products and arrival time of orders (see e.g. Bortolini et al. 2016), a function measuring the satisfaction level of the manufacturer, market and customers (e.g. Gholami et al. 2016) and shortage/responsiveness functions in the supply chain (e.g. Gen et al. 2006).

The model could be also extended to cover a multi-period settings by adopting shrimp maturity assumptions or even catching timeline. It might not be necessary to figure the model as a multi-product network because although there are different types of shrimp in the marine or aquaculture production, they are sold in a single deal. However, if this is not the case in some markets then prospective researchers can think about designing multi-product models.

Another valuable extension of this study is to consider the sustainability paradigm to make the model more comprehensive. Therefore, future researches may need to cover social, environmental, and economical aspects and include them in terms of constraints into the model. Moreover, in real-world settings uncertainty and ambiguity is common for different aspect of the supply chain network especially demand of markets. For future considerations, the model can be formulated as a stochastic model under uncertain condition of demands and other important parameters (e.g. Beraldi et al. 2000). Finally, further advances can be achieved even in the context of solution methodologies. For instance, developing stochastic and robust metaheuristic and heuristic approaches that can efficiently deal with the uncertain and multi-objective nature of the model can be a striking avenue.

References

Abdi A, Abdi A, Fathollahi-Fard AM, Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M (2019) A set of calibrated metaheuristics to address a closed-loop supply chain network design problem under uncertainty. Int J Syst Sci Oper Logist 1–18.

Abedi A, Zhu W (2017) An optimisation model for purchase, production and distribution in fish supply chain–a case study. Int J Prod Res 55(12):3451–3464

Agustina D, Lee CKM, Piplani R (2014) Vehicle scheduling and routing at a cross docking center for food supply chains. Int J Prod Econ 152:29–41

Ahumada O, Villalobos JR (2011) Operational model for planning the harvest and distribution of perishable agricultural products. Int J Prod Econ 133(2):677–687

Alam SMN (2016) Chapter 6-safety in the SSC. In: Prakash V, Martín-Belloso O, Keener L, Astley S, Braun S, McMahon H, Lelieveld HBT-RSofT, EF (Eds.) Academic Press, San Diego, pp. 99–123.

Al-Aomar R (2006) A GA-based parameter design for single machine turning process with high-volume production. Comput Ind Eng 50(3):317–337

Arnaout JPM, Maatouk M (2010) Optimization of quality and operational costs through improved scheduling of harvest operations. Int Trans Oper Res 17(5):595–605

Attanasio A, Fuduli A, Ghiani G, Triki C (2007) Integrated shipment dispatching and packing problems: a case study. J Math Model Algorit 6:77–85

Bakhrankova K, Midthun KT, Uggen KT (2014) Stochastic optimization of operational production planning for fisheries. Fish Res 157:147–153

Beraldi P, Musmanno R, Triki C (2000) Solving stochastic linear programs with restricted recourse using interior point methods. Comput Optim Appl 15(3):215–234

Blanchard EA, Loxton R, Rehbock V (2013) A computational algorithm for a class of non-smooth optimal control problems arising in aquaculture operations. Appl Math Comput 219(16):8738–8746

Borodin V, Bourtembourg J, Hnaien F, Labadie N (2016) Handling uncertainty in agricultural supply chain management: A state of the art. Eur J Oper Res 254(2):348–359

Bortolini M, Faccio M, Ferrari E, Gamberi M, Pilati F (2016) Fresh food sustainable distribution: cost, delivery time and carbon footprint three-objective optimization. J Food Eng 174:56–67

Bravo F, Durán G, Lucena A, Marenco J, Morán D, Weintraub A (2013) Mathematical models for optimizing production chain planning in salmon farming. Int Trans Oper Res 20(5):731–766

Buritica NC, Escobar JW, Sánchez LVT (2017) Designing a sustainable supply network by using mathematical programming: a case of fish industry. Int J Ind Syst Eng 27(1):48–72

Butterworth K (1985) Practical application of linear/integer programming in agriculture. J Oper Res Soc 36(2):99–107

Caixeta-Filho JV (2006) Orange harvesting scheduling management: a case study. J Oper Res Soc 57(6):637–642

Černý V (1985) Thermodynamical approach to the traveling salesman problem: an efficient simulation algorithm. J Optim Theory Appl 45(1):41–51

Cheraghalipour A, Paydar MM, Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M (2018) A bi-objective optimization for citrus closed-loop supply chain using Pareto-based algorithms. Appl Soft Comput 69:33–59

Cheraghalipour A, Paydar MM, Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M (2019) Designing and solving a bi-level model for rice supply chain using the evolutionary algorithms. Comput Electron Agric 162:651–668

Chiang WC, Russell RA (2004) Integrating purchasing and routing in a propane gas supply chain. Eur J Oper Res 154(3):710–729

Cisternas F, Donne DD, Durán G, Polgatiz C, Weintraub A (2013) Optimizing salmon farm cage net management using integer programming. J Oper Res Soc 64(5):735–747

Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme, Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme. Text by Peteri, A. In: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department [online]. Rome. Updated 1 January 2004. [Cited 3 December 2018]

Dai Z, Aqlan F, Zheng X, Gao K (2018) A location-inventory supply chain network model using two heuristic algorithms for perishable products with fuzzy constraints. Comput Ind Eng 119:338–352

De Grave S, Fransen CHJM (2011) Carideorum catalogus: the recent species of the dendrobranchiate, stenopodidean, procarididean and caridean shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda). Zool Med 9.

Deng W, Zhao H, Zou L, Li G, Yang X, Wu D (2017) A novel collaborative optimization algorithm in solving complex optimization problems. Soft Comput 21(15):4387–4398

Deroussi L (2016) Metaheuristics for logistics. John Wiley & Sons

Diarrassouba I, Labidi MK, Mahjoub AR (2019) A parallel hybrid optimization algorithm for some network design problems. Soft Comput 23(6):1947–1964

Eskandari-Khanghahi M, Tavakkoli-Moghaddam R, Taleizadeh AA, Amin SH (2018) Designing and optimizing a sustainable supply chain network for a blood platelet bank under uncertainty. Eng Appl Artif Intell 71:236–250

Fahimnia B, Davarzani H, Eshragh A (2018) Planning of complex supply chains: A performance comparison of three metaheuristic algorithms. Comput Oper Res 89:241–252

Fathollahi-Fard AM, Gholian-Jouybari F, Paydar MM, Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M (2017) A bi-objective stochastic closed-loop supply chain network design problem considering downside risk. Ind Eng Manage Syst 16:342–362

Fathollahi-Fard AM, Hajaghaei-Keshteli M (2018) A tri-level location-allocation model for forward/reverse supply chain. Appl Soft Comput 62:328–346

Fathollahi-Fard AM, Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M (2018) A stochastic multi-objective model for a closed-loop supply chain with environmental considerations. Appl Soft Comput 69:232–249

Fathollahi-Fard AM, Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M, Mirjalili S (2018a) Multi-objective stochastic closed-loop supply chain network design with social considerations. Appl Soft Comput 71:505–525

Fathollahi-Fard AM, Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M, Mirjalili S (2018b) Hybrid optimizers to solve a tri-level programming model for a tire closed-loop supply chain network design problem. Appl Soft Comput 70:701–722

Fathollahi-Fard AM, Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M, Mirjalili S (2020) A set of efficient heuristics for a home healthcare problem. Neural Comput Appl 32(10):6185–6205

Ferrer JC, Mac Cawley A, Maturana S, Toloza S, Vera J (2008) An optimization approach for scheduling wine grape harvest operations. Int J Prod Econ 112(2):985–999

Forsberg OI (1996) Optimal stocking and harvesting of size-structured farmed fish: a multi-period linear programming approach. Math Comput Simul 42(2–3):299–305

Forsberg OI (1999) Optimal harvesting of farmed Atlantic salmon at two cohort management strategies and different harvest operation restrictions. Aquac Econ Manag 3(2):143–158

Gen M, Altiparmak F, Lin L (2006) A genetic algorithm for two-stage transportation problem using priority-based encoding. OR Spectrum 28(3):337–354

Gholami F, Paydar MM, Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M, Cheraghalipour A (2019) A multi-objective robust supply chain design considering reliability. J Ind Prod Eng 36(6):385–400

Golshahi-Roudbaneh A, Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M, Paydar MM (2017) Developing a lower bound and strong heuristics for a truck scheduling problem in a cross-docking center. Knowl-Based Syst 129:17–38

González-Araya MC, Soto-Silva WE, Espejo LGA (2015) Harvest planning in apple orchards using an optimization model. In Handbook of operations research in agriculture and the agri-food industry (pp. 79–105). Springer, New York, NY.

Govindan K, Jafarian A, Nourbakhsh V (2015) Bi-objective integrating sustainable order allocation and sustainable supply chain network strategic design with stochastic demand using a novel robust hybrid multi-objective metaheuristic. Comput Oper Res 62:112–130

Govindan K, Jafarian A, Khodaverdi R, Devika K (2014) Two-echelon multiple-vehicle location–routing problem with time windows for optimization of sustainable supply chain network of perishable food. Int J Prod Econ 152:9–28

Govindan K, Kadziński M, Sivakumar R (2017) Application of a novel PROMETHEE-based method for construction of a group compromise ranking to prioritization of green suppliers in food supply chain. Omega 71:129–145

Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M, Aminnayeri M (2013) Keshtel Algorithm (KA); a new optimization algorithm inspired by Keshtels’ feeding. In Proceeding in IEEE conference on industrial engineering and management systems (pp. 2249–2253).

Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M, Fathollahi Fard AM (2018) Sustainable closed-loop supply chain network design with discount supposition. Neural Computing and Applications, 1–35.

Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M, Sajadifar SM (2010) Deriving the cost function for a class of three-echelon inventory system with N-retailers and one-for-one ordering policy. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 50(1–4):343–351

Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M, Sajadifar SM, Haji R (2011) Determination of the economical policy of a three-echelon inventory system with (R, Q) ordering policy and information sharing. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 55(5–8):831–841

Hanne T, Dornberger R (2017) Introduction to logistics and supply chain management. In: Computational intelligence in logistics and supply chain management. international series in operations research & management science, vol 244. Springer, Cham

Harlioglu MM, Farhadi A (2017) Iranian fisheries status: an update (2004–2014). Fish Aquac J 8(1):1E-1E

Holland JH (1992) Genetic algorithms Scientific american 267(1):66–73

Jabbarizadeh F, Zandieh M, Talebi D (2009) Hybrid flexible flowshops with sequence-dependent setup times and machine availability constraints. Comput Ind Eng 57(3):949–957

Jensen TK, Nielsen J, Larsen EP, Clausen J (2010) The fish industry—toward supply chain modeling. J Aquat Food Prod Technol 19(3–4):214–226

Jo JB, Li Y, Gen M (2007) Nonlinear fixed charge transportation problem by spanning tree-based

Kaasgari MA, Imani DM, Mahmoodjanloo M (2017) Optimizing a vendor managed inventory (VMI) supply chain for perishable products by considering discount: Two calibrated metaheuristic algorithms. Comput Ind Eng 103:227–241

Kirkpatrick S, Gelatt CD, Vecchi MP (1983) Optimization by simulated annealing. science, 220(4598), 671–680.

Kumar M, Vrat P, Shankar R (2006) A multi-objective 3PL allocation problem for fish distribution. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 36(9):702–715

Lin DY, Wu MH (2016) Pricing and inventory problem in SSC: A case study of Taiwan’s white shrimp industry. Aquaculture 456:24–35

Ma X, Wang S, Islam SM, Liu X (2019) Coordinating a three-echelon fresh agricultural products supply chain considering freshness-keeping effort with asymmetric information. Appl Math Model 67:337–356

Mansouri N, Javidi MM (2020) A review of data replication based on meta-heuristics approach in cloud computing and data grid. Soft Computing, 1–28.

Miller WA, Leung LC, Azhar TM, Sargent S (1997) Fuzzy production planning model for fresh tomato packing. Int J Prod Econ 53(3):227–238

Musavi M, Bozorgi-Amiri A (2017) A multi-objective sustainable hub location-scheduling problem for perishable food supply chain. Comput Ind Eng 113:766–778

Naderi B, Khalili M, Tavakkoli-Moghaddam R (2009) A hybrid artificial immune algorithm for a realistic variant of job shops to minimize the total completion time. Comput Ind Eng 56(4):1494–1501

Pathumnakul S, Piewthongngam K, Khamjan S (2009) Integrating a shrimp-growth function, farming skills information, and a supply allocation algorithm to manage the SSC. Comput Electron Agric 66(1):93–105

Rocco CD, Morabito R (2016) Production and logistics planning in the tomato processing industry: A conceptual scheme and mathematical model. Comput Electron Agric 127:763–774

Sanders BJ, Fadel JG, Wade EM (2003) Economic optimization modeling of white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) caviar and meat production under different management conditions. Aquaculture 217(1–4):409–430

Sarvestani HK, Zadeh A, Seyfi M, Rasti-Barzoki M (2019) Integrated order acceptance and supply chain scheduling problem with supplier selection and due date assignment. Appl Soft Computi 75:72–83

Schiller L, Bailey M, Jacquet J, Sala E (2018) High seas fisheries play a negligible role in addressing global food security. Sci Adv 4(8), eaat8351.

Sel C, Bilgen B, Bloemhof-Ruwaard JM, van der Vorst JG (2015) Multi-bucket optimization for integrated planning and scheduling in the perishable dairy supply chain. Comput Chem Eng 77:59–73

Sharma YK, Mangla SK, Patil PP, Uniyal S (2018) Sustainable food supply chain management implementation using DEMATEL approach. In: Advances in health and environment safety (pp. 115–125). Springer, Singapore.

Soto-Silva WE, González-Araya MC, Oliva-Fernández MA, Plà-Aragonés LM (2017) Optimizing fresh food logistics for processing: application for a large Chilean apple supply chain. Comput Electron Agric 136:42–57

Soto-Silva WE, Nadal-Roig E, González-Araya MC, Pla-Aragones LM (2016) Operational research models applied to the fresh fruit supply chain. Eur J Oper Res 251(2):345–355

Tabbakh T, Freeland-Graves JH (2016) The home environment: a mediator of nutrition knowledge and diet quality in adolescents. Appetite 105:46–52

Tabrizi S, Ghodsypour SH, Ahmadi A (2018) Modelling three-echelon warm-water fish supply chain: A bi-level optimization approach under Nash–Cournot equilibrium. Applied Soft Computing, 71, 1035–1053.

Taguchi, G. (1986). Introduction to quality engineering: designing quality into products and processes (No. 658.562 T3).

Talbi EG (2009) Metaheuristics: from design to implementation (Vol. 74). Wiley, London.

Tan B, Çömden N (2012) Agricultural planning of annual plants under demand, maturation, harvest, and yield risk. Eur J Oper Res 220(2):539–549

Teimoury E, Nedaei H, Ansari S, Sabbaghi M (2013) A multi-objective analysis for import quota policy making in a perishable fruit and vegetable supply chain: A system dynamics approach. Comput Electron Agric 93:37–45

Ten Berge HFM, Van Ittersum MK, Rossing WAH, Van de Ven GWJ, Schans J (2000) Farming options for The Netherlands explored by multi-objective modelling. Eur J Agron 13(2–3):263–277

Torkaman S, Ghomi SF, Karimi B (2018) Hybrid simulated annealing and genetic approach for solving a multi-stage production planning with sequence-dependent setups in a closed-loop supply chain. Appl Soft Comput 71:1085–1104

Triki C (2016) Location-based techniques for the synergy approximation in combinatorial transportation auctions. Optim Lett 10(5):1125–1139

Van Engeland J, Beliën J, De Boeck L, De Jaeger S (2018) Literature review: strategic network optimization models in waste reverse supply chains. Omega.

Wang Z, Soleimani H, Kannan D, Xu L (2016) Advanced cross-entropy in closed-loop supply chain planning. J Clean Prod 135:201–213

Wu X, Nie L, Xu M, Yan F (2018) A perishable food supply chain problem considering demand uncertainty and time deadline constraints: modeling and application to a high-speed railway catering service. Transp Res Part E Logist Transp Rev 111:186–209

Wunderlich SM, Martinez NM (2018) Conserving natural resources through food loss reduction: production & consumption stages of the food supply chain. International Soil and Water Conservation Research.

Yousefi K, Afshari J, A., & Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. (2018) Heuristic approaches to solve the fixed-charge transportation problem with discount supposition. J Ind Prod Eng 35(7):444–470

Yu R, Leung P (2005) Optimal harvesting strategies for a multi-cycle and multi-pond shrimp operation: a practical network model. Math Comput Simul 68(4):339–354

Yu R, Leung P, Bienfang P (2006) Optimal production schedule in commercial shrimp culture. Aquaculture 254(1–4):426–441

Yu R, Leung P, Bienfang P (2009) Modeling partial harvesting in intensive shrimp culture: a network-flow approach. Eur J Oper Res 193(1):262–271

Zheng YJ, Ling HF (2013) Emergency transportation planning in disaster relief supply chain management: a cooperative fuzzy optimization approach. Soft Comput 17(7):1301–1314

Zhu KJ, Wang DY (2012) Application of hybrid GA–SA heuristics for single-job production–delivery scheduling problem with inventory and due date considerations. Int J Ind Syst Eng 12(3):259–279

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author Behzad Mosallanezhad declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author Mostafa Hajiaghaei-Keshteli declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author Chefi Triki declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mosallanezhad, B., Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. & Triki, C. Shrimp closed-loop supply chain network design. Soft Comput 25, 7399–7422 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-021-05698-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-021-05698-1