Abstract

The French Mediterranean area is subject to intense rainfall events which might cause flash floods, the main natural hazard in the area. Flood-risk rainfall is defined as rainfall with a high spatial average and encompasses rainfall which might lead to flash floods. We aim to compare eight multivariate density models for multi-site flood-risk rainfall. In particular, an accurate characterization of the spatial variability of flood-risk rainfall is crucial to help understand flash flood processes. Daily data from eight rain gauge stations at the Gardon at Anduze, a small Mediterranean catchment, are used in this work. Each multivariate density model is made of a combination of a marginal model and a dependence structure. Two marginal models are considered: the Gamma distribution (parametric) and the Log-Normal mixture (non-parametric). Four dependence structures are included in the comparison: Gaussian, Student t, Skew Normal and Skew t in increasing order of complexity. They possess a representative set of theoretical properties (symmetry/asymmetry and asymptotic dependence/independence). The multivariate models are compared in terms of three types of criteria: (1) separate evaluation of the goodness-of-fit of the margins and of the dependence structures, (2) model selection with a leave-one-out evaluation of the Anderson-Darling and Cramer-Von Mises statistics and (3) comparison in terms of two hydrologically interpretable quantities (return periods of the spatial average and conditional probabilities of exceedances). The key outcome of the comparison is that the Skew Normal with the Log-Normal mixture margins outperform significantly the other models. The asymmetry introduced by the Skew Normal is an added-value with respect to the Gaussian. Therefore, the Gaussian dependence structure, although widely used in the literature, is not recommended for the data in this study. In contrast, the asymptotically dependent models did not provide a significant improvement over the asymptotically independent ones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The French Mediterranean area is subject to intense rainfall events occurring mainly in the fall. They can be triggered by a combination of three factors: the moisture generated by the Mediterranean Sea, upper-level cold troughs coming from the North and the complex orography in the region (the Alps, the Pyrenees and the Massif Central Mountains in the South of France) (Delrieu et al. 2005). Such heavy rainfall might cause flash floods that can be defined as a sudden rise of the water level (in a few hours or less) together with a significant peak discharge (Braud et al. 2014). Flash floods can potentially cause fatalities and important material damage and are known as the main natural hazard in the Mediterranean area (Borga et al. 2011). We refer to rainfall which might lead to flash floods as flood-risk rainfall.

A key feature of flood-risk rainfall is its strong spatial variability at high temporal and spatial resolutions. Indeed, Gaume et al. (2009) stressed that albeit flash floods are generally associated with localized intense rainfall that lasts a few hours, they can also be generated by long lasting rainfall with moderate intensities that affects the whole catchment. In the French Mediterranean region, streamflow simulation accuracy and dynamics can be significantly enhanced when exploiting information from rainfall at higher spatial resolution (Lobligeois et al. 2014; Patil et al. 2014; Braud et al. 2014). Therefore, analyses to characterize the spatial variability of flood-risk rainfall will contribute to the understanding of flash flood processes.

We define flood-risk rainfall as rainfall with a high spatial average. More precisely, the spatial average is high when it is above a threshold that should be set according to the catchment at hand. This definition encompasses both intense localized events and moderate widespread events, in accordance with expert knowledge. It is straightforward to cast flood-risk rainfall modeling with such a definition into a multivariate or spatial process extreme-value theory (EVT) framework (Coles 2001; Beirlant et al. 2006). In the peaks-over-threshold approach of EVT, models are developed for multivariate or spatial extremes defined as events which are large according to a given norm. With the \({\mathcal {L}}_1\)-norm, this corresponds exactly to the definition of flood-risk rainfall (see Sabourin and Naveau 2014 who proposed a non-parametric multivariate model in this framework). However, the application of these models to flood-risk rainfall raises a number of technical questions (for example, an extreme in the hydrological sense might not be an extreme in the statistical sense).

An alternative approach to analyze and characterize flood-risk rainfall is by means of stochastic rainfall generators (or more generally weather generators, see Ailliot et al. 2015). They can simulate long series of observations from which observations corresponding to flood-risk rainfall (high spatial average) can be extracted and studied. Stochastic generators are complex statistical models which must handle rainfall intermittency (the determination of rainy and dry areas) and rainfall inhomogeneity (the presence of different types of rainfall such as convective and stratiform and of seasonal or diurnal cycles). Intermittency can be addressed either by including an atom at zero in the transformation of the marginal distribution (Bouvier et al. 2003; Vischel et al. 2009; Baxevani and Lennartsson 2015) or by applying an indicator function (Barancourt et al. 1992; Wilks 1998; Hughes et al. 1999; Kleiber et al. 2012; Leblois and Creutin 2013). Inhomogeneity can be incorporated by means of rainfall or weather patterns (Bellone et al. 2000; Thompson et al. 2007; Garavaglia et al. 2010) or by introducing covariates in the distribution parameters (Chandler and Wheater 2002; Kleiber et al. 2012; Baxevani and Lennartsson 2015).

The spatial dependence structure of rainfall is an essential building block of multi-site stochastic generators. Many rely on the meta-Gaussian distributions, i.e. the Gaussian dependence structure combined with a transformation of the marginal distributions (Lebel and Laborde 1988; Wilks 1998; Guillot and Lebel 1999; Bouvier et al. 2003; Vischel et al. 2009; Kleiber et al. 2012; Leblois and Creutin 2013; Serinaldi and Kilsby 2014; Baxevani and Lennartsson 2015). Other multivariate distributions have been employed, with possibly a transformation of the marginals, to infer the spatial structure in stochastic generators but none, as far as we are aware, in a truly multi-site framework (see Flecher et al. 2010 for a single-site multi-variable weather generator based on the multivariate Skew Normal distribution and Vrac et al. 2007 for a two-site rainfall generator merging a bivariate Gamma with a bivariate model from EVT). The dependence structure can also be modeled with copulas (Genest and Favre 2007). Besides the Gaussian copula which is equivalent to the meta-Gaussian distribution, several copula families exist such as the Student t, the Archimedean or Extreme Value families but not many are available in dimension greater than two. For instance, Schoelzel and Friederichs (2008) performed modeling of rainfall at two sites with a bivariate Gumbel copula, Bárdossy and Pegram (2009) proposed an asymmetric copula to model rainfall at 32 sites and Serinaldi (2009) proposed a copula-based mixed model for bivariate rainfall.

Extreme rainfall in the French Mediterranean area has been widely studied. To our knowledge, most of the time, a univariate viewpoint is adopted with the block maxima approach of EVT where extreme events are taken as maxima over a period of time such as the year or the month, see Gardes and Girard (2010), Ceresetti et al. (2012) and Carreau et al. (2013) for instance. In contrast, spatial dependence is taken into account in Lebel and Laborde (1988) who proposed a geostatistical approach to model monthly areal rainfall maxima and in Neppel et al. (2011) who developed a multivariate regional test in which the spatial dependence structure is modeled with the Student t copula.

Comparison studies of spatial or multivariate models for extremes were conducted in other application domains or in other study areas. The meta-Gaussian distribution is often chosen because it is easy to implement even in high dimension. However, the Gaussian has very specific dependence properties which should be validated. In finance, impacts on risk measures of the choice of the Gaussian dependence structure compared to other choices were studied in Embrechts et al. (2002) and Poon et al. (2004). In particular, Embrechts et al. (2002) emphasized the potential under-estimation of the probability of joint extreme events when employing the Gaussian copula. In hydrology, Berg and Aas (2009) modeled daily rainfall at four sites with five types of combined Archimedean copulas and compared the goodness-of-fit with the Cramer-Von-Mises statistics. In Dupuis and Tawn (2001), the effects of mis-specification of the dependence structure on bivariate extreme-value problems were studied on synthetic data while Dupuis (2007) showed the effect of model mis-specification on bivariate hydrometric data sets. More recently, Blanchet and Davison (2011) and Thibaud et al. (2013) (see also references therein) performed model selection of spatial processes for extremes of snow and rainfall, respectively, in Switzerland. These studies show that the choice of the spatial dependence structure for extremes must be made with great care and that the meta-Gaussian distribution can fit very poorly.

In this work, we aim to analyze and compare multivariate density models for multi-site flood-risk rainfall. In particular, we seek to evaluate whether the spatial dependence properties of the models can reproduce the spatial variability of flood-risk rainfall. The study area is a small representative French Mediterranean catchment, the Gardon at Anduze, that is vulnerable to devastating floods (Delrieu et al. 2005). Flood-risk rainfall can be thought of as a type of rainfall (or rainfall pattern) and the strategy that we adopt in this work can thus be seen as focussing on a single rainfall type within a stochastic generator. The flood-risk rainfall type is the most important feature multi-site stochastic generators should be able to reproduce when applied in small Mediterranean catchments. In addition, the adopted strategy is likely to reduce the need to deal with rainfall intermittency and inhomogeneity, as is the case for the Gardon at Anduze catchment. This work is intended as a preliminary study before developing a spatial stochastic rainfall generator adapted for flood-risk rainfall in the Mediterranean area.

The paper is structured as follows. Daily flood-risk rainfall data at eight rain gauge stations in the Gardon at Anduze catchment together with pairwise exploratory analyses are presented in Sect. 2. Although the response time of the catchment is in the order of the hours, we make do with analyses at the daily time-step because a longer and more complete data base is available. We assume that the dependence structure of flood-risk rainfall at the daily time-step provides relevant information on the flash flood processes, even when they occur at the sub-daily scale. Section 3 is dedicated to the description of the eight multivariate density models included in the comparison. Each model consists of marginal distributions, which describe the univariate behavior of daily flood-risk rainfall at each site, combined with a spatial dependence structure, which captures the site-to-site variability at a given day. A parametric marginal model, the Gamma distribution, and a non-parametric marginal model, the mixture of Log-Normal distributions, are described in Sect. 3.1. Four dependence structures, the Gaussian, the Student t, the Skew Normal and the Skew t, in increasing order of complexity, are presented in Sect. 3.2. They possess a representative set of theoretical properties (symmetry/asymmetry and asymptotic dependence/independence for the extremes) and they can be fitted in dimension 8 with available R libraries (Kojadinovic and Yan 2010; Azzalini 2015). Section 4 contains the comparative results in terms of three types of criteria. We first examine separately the goodness-of-fit of the marginal models and of the dependence structures in Sect. 4.1. Second, the best model is selected by performing leave-one-out validation (also called jackknife) with two goodness-of-fit statistics, Cramer-Von Mises and Anderson-Darling, in Sect. 4.2. Third, we look at hydrologically interpretable quantities (return periods of observed spatial average and conditional probability of exceedances, see Thibaud et al. 2013 for similar criteria) which involve the whole multivariate models in Sect. 4.3. We discuss the results and conclude in Sect. 5.

2 Data and exploratory analyses

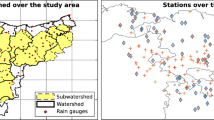

The catchment of the Gardon at Anduze is a small catchment of about 545 km2 located in the Cevennes mountain range, in the South of France, see Fig. 1a. It is subject to the Mediterranean climate that, in combination with its sharp orography, can trigger heavy precipitation events especially in the fall season (Ducrocq et al. 2008). Daily rainfall observations are collected over a 43 year period, from 01/01/1958 to 12/31/2000, at eight stations scattered around the catchment, as shown in Fig. 1b and Table 1. Horizontal distance for pairs of stations varies between 5 and 40 km. Elevation ranges from 135 m, in the valleys, to 930 m near the crest of the mountain range.

Based on expert knowledge on the Gardon catchment (Bouvier et al. 2007), we established that rainfall with a spatial average above 50 mm can potentially provoke flooding. In this work, flood-risk rainfall is thus defined as rainfall at the eight rain-gauges provided that the spatial average is above the threshold of 50 mm. Let \({\varvec{X}} = (X_{1}, X_{2}, \ldots , X_{8})\) be the vector of random variables of the rainfall intensities at each of the eight rain-gauges. Then, flood-risk rainfall corresponds to the following set:

Out of the 15,706 days of the 43 year observation period, 265 are such that the spatial average is above 50 mm. This is less than 2 % of all the observations and about 5.5 % of the days where it rains (defined as days for which at least one station receives more than 1 mm). Among the \(8 \times 265 = 2120\) observations, only four are zero. Hence, in order to keep the statistical models as parsimonious as possible, we chose not to model rainfall intermittency. Instead, we assume that rainfall intensities on flood-risk days are strictly positive at every station and these four zero observations are lifted to 0.2 mm, the rain-gauge measurement error.

Although preliminary analyses detect some order 1 auto-correlation when flood-risk rainfall happens on two consecutive days, i.e. \(Cor({\varvec{X}}_t, {\varvec{X}}_{t+1})\), we model \({\varvec{X}}_t\) as independent. As a result, the confidence intervals presented in the analyses might be narrower than if temporal dependence was taken into account, since the effective number of observations might be somewhat reduced. Consecutive flood-risk rainfall days occur 43 times and the largest magnitude of the auto-correlation is about 0.3 so we expect that the independence assumption does not have very significant impacts.

We further assume that flood-risk rainfall is identically distributed (homogeneity assumption). Flood-risk rainfall happens mainly during the fall season but there are occurrences throughout the year. It is likely that both convective and stratiform types of rainfall are included in our definition of flood-risk rainfall. In order to distinguish between the two of them, additional information, unavailable to us, such as the prevalent atmospheric circulation or sub-daily rainfall intensities, is needed. Since this information is rarely available, a classic way to attempt to ensure homogeneity is to perform separate modeling for each season or each month. The resulting model is a mixture with one component per season or per month, see Garavaglia et al. (2010) for example. For the catchment considered in this work, homogeneity would not be guaranteed by seasonal or monthly modeling as both convective and non-convective processes, known to yield heavy rainfall, can occur during the same season or the same month (Delrieu et al. 2005). Instead, we take a statistical approach to address the homogeneity assumption. We allow for mixture of distributions for the marginal models (Sect. 3.1) and for the dependence structures (Sect. 3.2.3). The adequate number of components is selected with the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (Schwarz 1978).

Country- and local-scale view of the catchment of the Gardon at Anduze in the South of France. a Map of metropolitan France; the catchment of interest is located within the orange rectangle depicted in the South. b The eight daily rain-gauge stations used in our study against a digital elevation map (m) revealing the sharp orography in the Cevennes mountain range

2.1 Pairwise dependence

Pairwise dependence is first evaluated with the estimation of Kendall’s \(\tau\) coefficients. Kendall’s \(\tau\) is a measure of dependence based on the difference between the probability of concordant and discordant pairs. Let \(X_i\) and \(X_j\) be two random variables representing flood-risk rainfall at station i and station j respectively. Then the \(\tau\) coefficient for these two stations is given by:

where \((\tilde{X}_i, \tilde{X}_j)\) is an independent copy of the pair \((X_i, X_j)\) with identical distribution. Kendall’s \(\tau\) is invariant to strictly increasing transformations (Joe 1997) and thus, it is unaffected by marginal transformations. It takes values in the interval \([-1,1]\), where \(\tau =-1\) or \(\tau =1\) means perfect negative or positive dependence and \(\tau =0\) means independence.

Kendall’s \(\tau\) coefficients, significantly different from zero at the 5 % level, are presented in the upper triangular part of Fig. 2. Pairwise scatterplots are shown in the lower triangular part of Fig. 2 together with a smooth regression line obtained from local regression (Cleveland 1981) to help detect dependencies. Figure 2 reads as follows. Each station name and histogram appears on the diagonal. Row i and column i concerns the \(i{\text {th}}\) station. At the intersection of column i and row j, with \(j > i\), there is the scatterplot of the pair of stations i (x-axis) and j (y-axis). Conversely, at the intersection of column j and row i, the corresponding Kendall’s \(\tau\) coefficient is written when significant at the 5 % level. The axes shown can be associated to the lower triangular scatterplots or to the histograms on the diagonal.

As is well recognized in the literature (Serinaldi and Kilsby 2014), Kendall’s \(\tau\) depends on the distance between the stations. For the flood-risk rainfall data, the \(\tau\) estimates appear to be linearly decreasing with the horizontal distance, as shown in Fig. 3 with a regression line. Kendall’s \(\tau\) for pairs of stations which are less than about 12 km apart ranges from 0.4 to 0.7 and then decreases to values close to zero or negative for stations which are more than 25 km apart.

Evaluation of pairwise dependence for the eight rain gauge stations. Diagonal: station names and histogram of flood-risk rainfall. Lower triangle: scatterplot of the flood-risk rainfall (black dots) with a locally smoothed regression “lowess” line. Upper triangle: Kendall’s \(\tau\) coefficient significant at the 5 % level

We consider a second measure of pairwise dependence, the \(\chi\) coefficient, which measures extremal dependence (Coles et al. 1999). For a pair of variables \((X_i, X_j)\), it is defined as:

where \(F_{X_i}\) and \(F_{X_j}\) are the distribution functions of \(X_i\) and \(X_j\) respectively. Loosely stated, \(\chi\) is the probability of one variable being extreme given that the other is extreme. Since \(\chi\) is the limit of a conditional probability, it takes values in [0, 1]; when \(\chi =0\), \(X_i\) and \(X_j\) are said to be asymptotically independent whereas when \(\chi > 0\), they are asymptotically dependent (perfect dependence is achieved when \(\chi =1\)). In practice, \(\chi\) is estimated for a fixed threshold u, taken as high as possible.

A useful tool to assess whether a pair of variables \(X_i\) and \(X_j\) is asymptotically dependent or independent is the so-called \(\chi\)-plot (Coles et al. 1999). In such a plot, \(\chi (X_i, X_j)\) is estimated and plotted against increasing thresholds u expressed as quantiles of level \(q \in [0,1]\). Confidence intervals can be constructed with the delta method but are not very reliable near \(q=0\) or \(q=1\).

In the flood-risk rainfall data, both asymptotically dependent and independent pairs of stations appear to be present. In Fig. 4, the \(\chi\)-plots for two representative pairs of stations are shown together with a 95 % confidence interval (R package evd Stephenson 2002). The \(\chi\)-plot of the pair of nearby stations, Barre-des-Cevennes and Cassagnas, in Fig. 4a, is rather stable around the value 0.6, regardless of the threshold, and thus indicates asymptotic dependence. In contrast, for the pair of distant stations, Barre-des-Cevennes and Generargues, in Fig. 4b, the \(\chi\) estimates increase from negative values (which are caused by the estimator employed, see Coles et al. 1999) to values near zero, indicative of asymptotic independence.

As discussed in Serinaldi et al. (2014), \(\chi\) estimators are strongly positively related to Kendall’s \(\tau\) coefficients. In Fig. 5, the \(\chi\) estimates for the flood-risk rainfall data with a threshold u set to the 95 % quantile (R package extRemes from Gilleland and Katz 2011) are plotted with respect to the \(\tau\) estimates. When the \(\tau\) estimates are positive, the scatter plot is quite well aligned with the \(y=x\) line.

Two representative \(\chi\)-plots: \(\chi\) estimates with respect to u with 95 % confidence intervals (black dashed lines). a Two nearby stations Barre-des-Cevennes and Cassagnas. The \(\chi\)-plot indicates asymptotic dependence. b Two distant stations Barre-des-Cevennes and Generargues. The \(\chi\)-plot indicates asymptotic independence

3 Multivariate density models

3.1 Marginal distributions

The first marginal model considered is the Gamma distribution which has often been used to model daily precipitation (Chandler and Wheater 2002; Flecher et al. 2010; Kleiber et al. 2012). The Gamma density is given by:

where k and \(\eta\) are the shape and scale parameters respectively with \(k, \eta > 0\) and \(\Gamma (k)\) is the Gamma function evaluated at k. Estimates of k and \(\eta\) are obtained by the maximum likelihood estimation method (R package MASS from Venables and Ripley 2002).

We consider as a second marginal model a mixture of Log-Normal distributions although some authors recommend to model rainfall with a hybrid distribution. Such a hybrid distribution combines a parametric (Carreau and Bengio 2009; Li et al. 2012) or non-parametric model (Lennartsson et al. 2008) for the bulk of the distribution with the Generalized Pareto distribution (GPD) in the upper tail. Univariate extreme value theory (EVT) provides an asymptotic justification for the GPD to be an appropriate model for the distribution of values exceeding a suitably chosen high threshold (Pickands 1975). An advantage of such a hybrid distribution is its ability to adapt to any type of upper tail behavior be it finite, exponential (light-tail) or power-law (heavy-tail).

The motivation for the choice of the Log-Normal mixture instead of the hybrid distribution is twofold. First, preliminary analyses based on fitting the GPD revealed that the marginal distributions of the flood-risk rainfall data appear to be light-tailed. The Gamma is light-tailed but, because it has only two parameters, might lack the flexibility to model both the bulk of the rainfall distribution and its upper tail. Second, the Log-Normal mixture is straightforward to fit, has shown to be a good model for rainfall in Southen France (Carreau and Vrac 2011) and can take into account the presence of more than one sub-population of rainfall, such as convective and stratiform, if needed.

The number of mixture components must be chosen carefully according to the data set. Indeed, a mixture of distributions is a non-parametric model which mean that the complexity, that is the number of free parameters driven by the number of mixture components, can increase as the data set gets larger (Carreau and Bengio 2009). For all eight stations, two components in the Log-Normal mixture were selected with the BIC. We used the R package from Frayler and Raftery (1999) for Gaussian mixtures on log-transformed data. From a statistical viewpoint, the population of flood-risk rainfall at each station is adequately modeled with a two-component Log-Normal mixture. The marginal model, see Eq. (5), has thus 5 parameters \({\varvec{\psi}} = (\lambda ,\tilde{\mu }_1, \tilde{\sigma }_1,\tilde{\mu }_2, \tilde{\sigma }_2 )\) where \(\lambda \in [0,1]\) is the mixture proportion, \(\tilde{\mu }_i \in {\mathbb {R}}\) and \(\tilde{\sigma }_i > 0\), \(i=1,2\), are the location and scale parameters of the \(i{\text {th}}\) Log-Normal component.

3.2 Spatial dependence structures

3.2.1 Gaussian and student t copulas

The first two dependence structures included in the comparison are the Gaussian and Student t copulas which belong to the elliptical family (R package copula from Kojadinovic and Yan 2010). As a widespread model among practitioners, the Gaussian copula, that represents the class of meta-Gaussian models, is taken as the benchmark model. The Student t copula has an additional parameter, the degree of freedom \(\nu\), which provides greater modeling flexibility in terms of tail dependence and encompasses the Gaussian copula as a limiting case, when \(\nu \rightarrow \infty\).

As mentioned in Genest and Favre (2007), the main advantage of the copula approach is that a valid multivariate model can be built by selecting a dependence structure represented by the copula and then selecting independently the marginal distributions. Let \({\varvec{X}} \in {\mathcal {F}}\) be as in Eq. (1), the random vector of flood-risk rainfall intensities, let \(F_{X_j}\), \(j=1,\ldots , 8\) be its marginal distributions and \(F_{\varvec{X}}\) be its joint distribution function. Then, by Sklar’s theorem (Sklar 1959), the associated copula, assuming \({\varvec{X}}\) is continuous, is a function \(C_{\varvec{\theta }}:[0,1]^8 \rightarrow [0,1]\), with parameter vector \({\varvec{\theta}}\), such that:

There are no closed-form expressions for the Gaussian and Student t copulas as expressions for \(C_{\varvec{\theta }}\) can be obtained by means of the formula:

where \(F^{-1}_{X_j}\) denotes the quantile function of the margins that do not have closed-form expressions for the Gaussian and Student t distributions.

The Gaussian and Student t copula parameters stem from the parameters of their associated standardized multivariate distribution functions. This is because copulas, by definition, are invariant under a standardization of the marginal distributions. The expressions of the standardized densities are given in Eq. (8) for the Gaussian and Eq. (9) for the Student t with \({\varvec{x}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^d\). In the Gaussian case, the parameter vector \({\varvec{\theta }}\) contains the free parameters of the \(d \times d\) correlation matrix P which must be symmetric and positive definite. In the Student t case, \({\varvec{\theta }}\) contains, in addition to P, the degree of freedom parameter \(\nu > 0\).

For the Gaussian and Student t copulas, Kendall’s \(\tau\) takes the same form, see Eq. (10). It is positively related to the correlation parameter \(\rho _{ij}\) in the matrix P associated to the pair \((X_i,X_j)\) (Demarta and McNeil 2005). In regard to the variety of strengths of empirical Kendall’s \(\tau\) coefficients in the flood-risk rainfall data (see Fig. 2), we chose not to impose any specific parametric form on the correlation matrix P so that it has as much flexibility as needed.

In contrast, the extremal behavior of the Gaussian and Student t copulas differ. This can be analyzed through the \(\chi\)-coefficient of extremal dependence, defined in Eq. (3), that can be expressed in terms of the copula function, see Eq. (11). The Gaussian is asymptotically independent with \(\chi =0\), provided that \(|\rho _{ij}| < 1\) although this behavior might come into play only for very extreme values if \(\rho _{ij}\) is close enough to 1 (Coles et al. 1999). In contrast, the Student t is asymptotically dependent with positive \(\chi\) as long as \(\rho _{ij} > -1\) and \(\nu < \infty\) (Demarta and McNeil 2005). The smaller \(\nu\) is, the larger \(\chi\) becomes.

The copula parameters are estimated by the method of maximum pseudo-likelihood (MPL) that relies on the ranks of the observations (Genest and Favre 2007). This way, the estimation of the dependence structure is completely independent from the estimation of the marginal distributions. Provided that the density \(c_{\varvec{\theta }}\) associated to the copula exists, MPL involves the maximization of a log-likelihood of the form:

where \(\hat{F}_{X_s}(x_s)\), \(s=1, \ldots , 8\), are the marginal empirical distribution functions which depend essentially on the ranks.

The densities of the Gaussian and Student t copulas in the bivariate case are illustrated in Fig. 6a, b respectively. For both copulas, \(\rho =0.5\) and thus Kendall’s \(\tau\) is equal to 0.33, according to Eq. (10). The degree of freedom parameter is \(\nu =4\) which, together with \(\rho =0.5\), yields a coefficient of extremal dependence of \(\chi =0.25\) for the Student t copula (Demarta and McNeil 2005). The asymptotic dependence of the Student t copula is associated with a higher density of joint extremes, as can be seen by comparing the Gaussian and the Student t copulas in Fig. 6.

3.2.2 Skew normal and Skew t

The last two dependence structures included in the comparison are the multivariate Skew Normal and Skew t distributions (R package sn Azzalini 2015). They can be thought of as asymmetric extensions of their generating distribution (Gaussian for the Skew Normal and Student t for the Skew t). The Skew distributions have an additional vector of d parameters, \({\varvec{\alpha }}\), which act as skewness parameters. The Gaussian and Student t distributions appear as special cases when \({\varvec{\alpha }} = {0}\).

The density of the Skew Normal (resp. Skew t) are given in Eq. (13) (resp. Eq. (14)) where \({\varvec{x}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^d\) (Azzalini and Capitanio 2003). For both the Skew Normal and the Skew t, \({\varvec{\alpha }} \in {\mathbb {R}}^d\) projects \({\varvec{x}}\) onto a line and P is a \(d \times d\) correlation (or dispersion) matrix that is symmetric and positive definite. The Skew t has, in addition, the degree of freedom parameter, \(\nu > 0\), inherited from the Student t.

The densities of the Skew distributions from Eqs. (13–14) are obtained by multiplying the multivariate Gaussian density \(f^{\text {Gauss}}({\varvec{x}}; P)\) from Eq. (8) or the multivariate Student t density \(f^{\text {Stu}}({\varvec{x}}; P, \nu )\) from Eq. (9) by a skewing factor which is based on the univariate standard Gaussian distribution function \(F^{\text {Gauss}}(\cdot )\) or the univariate standard Student t distribution function with \(\nu +d\) degree of freedom \(F^{\text {Stu}}(\cdot ; \nu + d)\).

Since the Skew distributions include their generating distributions as special cases, we expect that they might share their pairwise dependence properties. In terms of Kendall’s \(\tau\), to our knowledge, no closed-form expressions were derived for the Skew distributions. In terms of \(\chi\)-coefficient, Bortot (2010) has shown that the Skew Normal is asymptotically independent (\(\chi = 0\)) and the Skew t is asymptotically dependent (\(\chi > 0\)) as it is the case for the symmetric distributions of Eq. (11). However, Bortot (2010) argued that the Skew distributions have greater flexibility and can adapt to a larger variety of extremal dependence strengths than their generating distributions.

In order to separate the inference of the margins from the inference of the spatial structure, we adapted the margin transformation proposed in (Flecher et al. 2010):

where \(\hat{F}_{X_s}(x_s)\), \(s=1, \ldots , 8\), are the marginal empirical distribution functions and \(H^{-1}\) is the quantile function of a suitable univariate distribution. When the spatial structure is the multivariate Skew Normal (resp. Skew t), the univariate standard Normal (resp. standard Student t with fixed degree of freedom parameter) is used in the transformation of Eq. (15). We did not employed copulas for skew distributions because they were not available yet in R packages although theoretical developments are underway (Kollo et al. 2013).

The parameters of the Skew distributions are estimated by maximizing the following log-likelihood:

where \(f^{\text {Skew}}\) is the density of either the Skew Normal from Eq. (13) or the Skew t from Eq. (14) with degree of freedom fixed to the value estimated for the Student t copula. Therefore, the parameter vector \({\varvec{\theta }}\) contains the free parameter of the \(8 \times 8\) correlation matrix P and the skewness parameters \({\varvec{\alpha }}\). In practice, the sn package (Azzalini 2015) did not allow to fix the location parameters to zero and the scale parameters to 1 in the estimation as would be required by the margin transformation. In order to stay as close as possible to these parameter values, they were used as starting parameter values for the optimization. The optimized parameter values did not wander too far from the starting values. The Skew t, the most complex model, was difficult to fit. Sensible starting values, taken from the fitted Skew Normal, were provided to the optimizer to help the estimation of the parameters.

Two types of departure from symmetry are illustrated in Fig. 7 in terms of bivariate copula density for the Skew Normal (left column) and the Skew t (right column). Copula densities are computed by deriving the expression in Eq. (6) with respect to \(x_i\), \(i=1, \dots , 8\) (see Kollo et al. 2013). In all four cases, \(\rho =0.5\) and \(\nu =4\) for the Skew t so that these copula densities can be compared to their symmetric counterparts in Fig. 6. In the top row, the skewness parameter is \(\alpha = (-1,1)\) and produces an asymmetry with respect to the line \(y = x\). In this case, the x-axis variable most often takes higher values than the y-axis variable. In the rainfall application, this translates into one station generally hitting higher quantile values of its marginal distribution with respect to another station. In the bottom row, \(\alpha = (0.5,0.5)\) yields an asymmetry with respect to the line \(y = 1 - x\). This results in lower dependence at the smaller values than at the larger values. This can be related to the fact that low rainfall intensities tend to be scattered and intermittent and thus often display poor spatial dependence whereas high rainfall intensities tend to be more dependent (Bárdossy and Pegram 2009).

Bivariate skew copula densities. a Skew Normal copula with \(\rho =0.5\) and \(\alpha = (-1,1)\). b Skew t copula with \(\rho =0.5\), \(\nu =4\) and \(\alpha = (-1,1)\). c Skew Normal copula with \(\rho =0.5\) and \(\alpha = (0.5,0.5)\). d Skew t copula with \(\rho =0.5\), \(\nu =4\) and \(\alpha = (0.5,0.5)\)

3.2.3 Multivariate mixture

In order to account for the possible presence of more than one sub-population of rainfall, we tested whether a multivariate mixture with more than one component was required. The margins of the flood-risk rainfall data were transformed to standard Gaussian with the empirical marginal distribution functions, see Eq. (15), and a multivariate Gaussian mixture was fitted to the transformed data. Then, the BIC was used to select the appropriate number of components (Frayler and Raftery 1999).

According to the BIC, a single Gaussian component is needed to model the dependence structure. We expect that only one component would be selected as well when considering a mixture with the other models (Student t, Skew Normal and Skew t). Indeed, these models include the Gaussian as a special case and have a larger number of parameters. For the BIC to select more than one component, the increase in goodness-of-fit versus the increase in complexity (number of parameters) would have to be very significant. The test provide sufficient grounds to keep a single dependence structure model and not to consider further multivariate mixture modeling.

4 Comparative results

4.1 Statistical inference

First, we seek to evaluate independently how good the marginal and dependence structure models are at fitting the flood-risk rainfall data.

4.1.1 Margin fit

The fit of the two marginal distributions considered is evaluated by means of quantile-quantile plots (qq-plots) as shown in Fig. 8 for the Gamma distribution and in Fig. 9 for the 2-component Log-Normal mixture. In all qq-plots, the empirical quantiles are represented on the x-axis and the theoretical quantiles from the marginal distributions on the y-axis. Confidence intervals at 95 % for the theoretical quantiles are computed with 1000 parametric bootstrap replications. To ease comparison across qq-plots, the first diagonal is drawn on the interval [0, 300]. For a given station, the marginal model is considered to fit well if the first diagonal is within the confidence interval most of the time.

The Gamma distribution fails at representing the upper tail and thus the largest observations of flood-risk rainfall at at least four stations (Barre-des-Cevennes, Ales, Lasalle and Saint-Christol-les-Ales). In contrast, the 2-component Log-Normal mixture yields a better fit at the expense of wider confidence intervals that are most likely due to the higher number of parameters (5 parameters as compared to 2 for the Gamma distribution).

Quantile–quantile plots of the Gamma distribution at each station with parametric bootstrap 95 % confidence interval. Empirical quantiles (theoretical quantiles) are on the x-axis (y-axis).The range of the first diagonal covers [0,300] on both axes in all plots. a Barre-des-Cevennes. b Cassagnas. c Lecollet-de-Deze. d Ales. e Generargues. f Lasalle. g Saint-Andre-de-Val. h Saint-Christol-les-A

Quantile–quantile plots of the 2-component Log-Normal mixture distribution at each station with parametric bootstrap 95 % confidence interval. Empirical quantiles (theoretical quantiles) are on the x-axis (y-axis).The range of the first diagonal covers [0,300] on both axes in all plots. a Barre-des-Cevennes. b Cassagnas. c Lecollet-de-Deze. d Ales. e Generargues. f Lasalle. g Saint-Andre-de-Val. h Saint-Christol-les-A

4.1.2 Dependence structure fit

There is no straightforward way to visually assess the fit of a dependence structure, especially in high dimension. We make do with comparisons in terms of pairwise dependence. First, we evaluate whether the models are able to reproduce the empirical Kendall’s \(\tau\) for all pairs of stations. We dropped the evaluation in terms of the extremal \(\chi\) coefficients as we have seen that the \(\chi\) estimators are positively related to the \(\tau\) coefficient estimators, see Fig. 5. Second, we look at bivariate densities for two representative pairs of stations.

All four dependence structures give theoretical Kendall’s \(\tau\) coefficients that are quite close to the empirical estimates, as can be seen in Fig. 10. For the Gaussian and Student t copulas, the theoretical \(\tau\) coefficients are computed thanks to the relationship with the correlation coefficients in Eq. (10). For the Skew distributions, the theoretical \(\tau\) coefficients are estimated by computing the empirical \(\tau\) estimates on random samples of size 5000 from the fitted distributions.

In order to gain more insight into the models, we also look at the fitted bivariate copula densities for the same two pairs of stations as chosen for illustration for the \(\chi\)-plots in Fig. 4: a nearby pair, Barre-des-Cevennes and Cassagnas, in Fig. 11 and a distant pair, Barre-des-Cevennes and Generargues, in Fig. 12.

The fitted bivariate copula densities are estimated with bivariate hexagonal histograms (R package fMultivar provided by Rmetrics https://www.rmetrics.org/) on random samples of size \(10^6\) from the copulas associated to each fitted model. We made this choice because the bivariate margins of the Skew distributions are not easy to deduce (Azzalini 2013). The darker the histogram bin is, the higher the density is estimated. The same scale of grey is used for each pair of stations. The dots represent the observations.

Figures 11, 12 are organized as follows. The asymptotically independent dependence structures are in the left column (Gaussian and Skew Normal) and the asymptotically dependent ones are in the right column (Student t and Skew t). The symmetric dependence structures are in the top row (Gaussian and Student t) while the asymmetric ones (Skew Normal and Skew t) are in the bottom row.

Although the theoretical Kendall’s \(\tau\) coefficients are very similar to the empirical ones (0.55 for Barre-des-Cevennes and Cassagnas and \(-0.067\) for Barre-des-Cevennes and Generargues), there might be important differences in the bivariate densities such as those observed for the distant pair, Barre-des-Cevennes and Generargues in Fig. 12. Therefore, assessing whether the empirical Kendall’s \(\tau\) coefficients are reproduced is clearly not enough to determine which model is the most appropriate.

Fitted bivariate copula densities for the nearby pair of stations (Barre-des-Cevennes and Cassagnas) as estimated by bivariate hexagonal histograms on random samples of size \(10^6\) from the copulas associated with each fitted model. The darker the histogram bin is, the higher the density is estimated. The dots represent the observations. The empirical Kendall’s \(\tau\) is 0.55. a Gaussian copula. b Student t copula. c Skew Normal. d Skew t

Fitted bivariate copula densities for the distant pair of stations (Barre-des-Cevennes and Generargues) as estimated by bivariate hexagonal histograms on random samples of size \(10^6\) from the copulas associated with each fitted model. The darker the histogram bin is, the higher the density is estimated. The dots represent the observations. The empirical Kendall’s \(\tau\) is \(-0.067\). a Gaussian copula. b Student t copula. c Skew Normal. d Skew t

4.2 Leave-one-out model selection

Second, model selection is achieved by performing an automatic quantitative evaluation of the fit of the multivariate density models based on leave-one-out validation (sometimes also called jackknife). With such a validation scheme, each observation is left aside in turn and the models are fitted on the \(n-1\) observations. Performance measures are then computed on the observation that was left aside. Since the performance is evaluated out-of-sample, the comparison is fair between models even when they have different numbers of parameters (see Chapter 2.7 in Ripley 1996).

We used the Cramer-Von Mises and Anderson-Darling goodness-of-fit statistics as performance measures. These goodness-of-fit statistics can be seen as distances between the empirical distribution function and the theoretical distribution function \(F_{\varvec{\phi }}\) of a given multivariate density model, with \({\varvec{\phi }}\) including margin and dependence parameters. The Cramer-Von Mises statistic is simply defined as the square distance between the two distribution functions while in the Anderson-Darling statistic, weights are introduced to emphasize an accurate representation of extreme values (Genest et al. 2013).

In the first step of the leave-one-out scheme, for a given \(1 \le k \le n\), we compute \(\hat{F}_{k:n-1}\), the empirical distribution function, and \(\hat{\varvec{\phi }}_{k:n-1}\), the parameter estimates of the theoretical distribution function, on sets of the form:

In the second step of the leave-one-out scheme, the goodness-of-fit statistics are evaluated on the left-out observation \({\varvec{X}}_k\) with the distribution functions fitted on \({\mathcal {F}}_{k:n-1}\). The expressions for the Cramer-Von Mises and the Anderson-Darling statistics are given in Eqs. (18) and (19) respectively.

Figure 13 shows the averages over \(1 \le k \le n\) and confidence intervals at 95 % from standard errors for the two statistics of Eqs. (18)–(19) for the eight multivariate density models. In the model acronyms (to the left of Fig. 13), GC and TC stand for Gaussian and Student t copula and SN and ST for Skew Normal and Skew t. The marginal models are indicated by Gam for Gamma (in blue) and LNormMix for the 2-component Log-Normal mixture (in black). The x-axis has a logarithmic scale to enhance differences between models. Smaller value of the statistics means a better performance.

Model selection based on the leave-one-out evaluation of the Cramer-Von Mises (CvM) and the Anderson-Darling (AD) goodness-of-fit statistics: average value and 95 % confidence interval are shown on a logarithmic scale. In blue, models with Gamma margins (Gam), and in black, with 2-component Log-Normal mixture margins (LNorMix). GC and TC stand for Gaussian and Student t copulas and SN and ST for Skew Normal and Skew t. The model SN-LNorMix outperforms significantly the other models

The multivariate model with the Skew Normal dependence structure and 2-component Log-Normal margins (SN-LNorMix) outperforms the other seven models in terms of both goodness-of-fit statistics. In all cases but one, the performance of the multivariate models, in terms of both goodness-of-fit statistics, is improved when 2-component Log-Normal mixture margins are used instead of Gamma margins. The exception concerns the models with Skew t dependence structure that have similar performance with both types of margins. When Gamma margins are employed, all four dependence structures yield multivariate models with comparable performance. Only the Skew Normal displays a significantly better fit and only in terms of the Anderson-Darling statistic. The asymptotically dependent models (TC, ST) are not performing better than their asymptotically independent counterparts (GC, SN).

4.3 Hydrological criteria

Last, we propose to obtain complementary insight into the multivariate models by means of two hydrologically meaningful quantities: the return periods of the spatial average of flood-risk rainfall (Sect. 4.3.1) and the conditional probability that at one station, rainfall exceeds a high level given that a high level is exceeded at another station (Sect. 4.3.2).

4.3.1 Spatial average return periods

The distribution of the spatial average \(\overline{X} = {X_1 + \cdots + X_8}/{8}\) and consequently of the return periods of the spatial average, involves both the margins and the dependence structure of the multivariate density models.

The empirical return periods of the observed spatial averages are computed as follows. Let \(\bar{x}_{(k)} = {\sum _{j=1}^8 x^{(k)}_j}/{8}\), be the \(k{\text {th}}\) largest observed spatial average, \(k = 1, \ldots , 265\), and let \(n_{\bar{x}} = {265}/{43} \approx 6.16\) be the average number of observations per year with a spatial average greater than 50 mm. Then, the empirical return period of \(\bar{x}_{(k)}\) is estimated by:

where \(P(\overline{X} > \bar{x}_{(k)} | \overline{X} > 50) \approx {(265.5-k)}/{265}\) are the empirical Hazen frequencies. For example, the return period of the smallest observed spatial average (50 mm) is estimated to \(\hat{T}_1 =0.163\) year or approximately 60 days whereas the return period of the largest observed spatial average (194 mm) is estimated to \(\hat{T}_{265} = 86\) years.

The theoretical return periods \(T_k\), that is as predicted by the fitted models, of the observed spatial averages are estimated by bootstrap resampling as computing exact return periods from the multivariate models would be very involved. An 8-dimensional sample of size \(10^6\) was drawn from each of the eight multivariate density models ensuring that the spatial average is always greater than 50. The theoretical return periods are then estimated with Eq. (20) in which \(P(\overline{X} > \bar{x}_{(k)} | \overline{X} > 50)\) is now approximated by the proportion of exceedances of \(\bar{x}_{(k)}\) in the bootstrap sample of \(10^6\) simulated spatial averages.

Confidence intervals at 95 % are obtained for the empirical and theoretical return periods as follows. For the empirical estimates \(\hat{T}_k\), since the size of the observed sample is small, bootstrap resampling is employed. To this end, 10,000 random samples of size 265 were drawn with replacement from the set of 265 8-dimensional observed rainfall so as to preserve spatial dependence. For the theoretical estimates \(T_k\), as the sample size is large, 95 % confidence intervals can be computed from standard errors. This is done in two steps. First, standard errors for the sample proportion of exceedances of \(\bar{x}_{(k)}\) are estimated as the standard deviation of the sample proportion divided by the square-root of the sample size (1000 in this case). The confidence intervals deduced for the sample proportion of exceedances are translated into confidence intervals for the return periods via Eq. (20).

Empirical and theoretical return periods in logarithmic scale are plotted against the observed spatial averages in Fig. 14. Each of the four panels is dedicated to one dependence structure in which the empirical estimates with their 95 % confidence intervals are shown as red dots surrounded by a grey band and the theoretical estimates appear as curves with confidence intervals pictured as tiny vertical bars (the model with Gamma margins is in blue and the model with 2-component Log-Normal mixture margins is in a black). The tiny vertical bars are hardly visible, they appear as small dots along the curves, this is because the confidence intervals for the theoretical estimates are very narrow. As in Figs. 11, 12, the effect of allowing for skewness can be assessed by comparing the top row with the bottom row and of allowing for asymptotic dependence by comparing left and right panels.

Empirical (red dots) and theoretical return periods (blue curve for the Gamma margins and black curve for the 2-component Log-Normal mixture margins) in logarithmic scale of the observed spatial average are plotted against the observed spatial averages. The 95 % confidence band of the empirical estimates are shown in grey while those of the theoretical estimates are the tiny vertical bars along the blue and black curves. a Gaussian copula. b Student t copula. c Skew Normal. d Skew t

The Skew Normal dependence structure stands out as it is the only one which, with both types of margins, is able to reproduce accurately the return periods of the smallest return levels (from 50 to 90 mm approximately). These are under-estimated by the other three dependence structures, which means that the models see these levels as more frequent than they should.

For the largest spatial averages (beyond 125 mm), the confidence intervals of the empirical estimates are very wide and contain, most of the time, the estimates of all eight models. These spatial averages are rare events (return periods greater than 30 years) with respect to the length of the data set (43 years). For the four dependence structures, the model with 2-component Log-Normal mixture margins yields lower return periods while the model with Gamma margins provides higher return periods and thus assigns smaller probabilities to the largest observed spatial averages.

4.3.2 Conditional probability of exceedance

Conditional probabilities can be deduced from the multivariate density models using their lower dimensional margins. We consider the conditional probability that rainfall at one station exceeds the at-site T-year return level given that it has exceeded the at-site T-year return level at another station in the catchment. For two stations i and j, this can be expressed as:

where \(R_i(T)\) and \(R_j(T)\) are the at-site T-year return levels for stations i and j that satisfy \(P(X_i > R_i(T)) = P(X_j > R_j(T)) = {1}/{T}\).

The at-site return levels are estimated individually by fitting the Generalized Pareto distribution (GPD) above a suitably high threshold (Coles 2001). For station j, the upper tail is approximated by the GPD, for all x above the threshold \(u_j\), as follows:

where \(\beta _j\) and \(\xi _j\) are the scale and shape parameters respectively of the GPD and the \(+\) indicates the positive fraction, that is \(z_+ = \max (z,0) \ \forall z \in {\mathbb {R}}\). The threshold \(u_j\) is set to the 95 % empirical quantile of the rainfall intensities greater than 1 mm. The T-year return level at station j can be derived from Eq. (22) as:

where \(P(X_j > u_j)\) is taken as the sample proportion of threshold exceedances.

The at-site return level estimates for \(T=2\), 5, 10 and 20 years at three stations that form the two pairs of representative stations examined before (see Sect. 4.1.2) are shown in Table 2. The first two stations, Barre-des-Cevennes and Cassagnas, are close spatially and sit near the mountain crest while the third station named Generargues lies in the valley and has lower return levels.

The empirical and theoretical (as predicted by each fitted model) conditional probabilities of Eq. (21) are estimated as the sample proportion of the conditional exceedances. In other words, among the observations in the sample for which \(R_i(T)\) is exceeded at station i, we computed the proportion for which \(R_j(T)\) is also exceeded at station j. For the theoretical conditional probabilities, a sample of size \(10^6\) was simulated by each fitted model such that the spatial average is greater then 50. As already mentioned, we resorted to simulation to estimate the theoretical conditional probabilities because the lower dimensional margins of the Skew distributions are not easy to deduce (Azzalini 2013).

The 95 % confidence intervals are estimated in a similar way as those for the return periods of the spatial average in Sect. 4.3.1. For the empirical estimates, as the sample size is small, 95 % confidence intervals are obtained by bootstrap resampling (10,000 random samples of size 265 were drawn with replacement from the set of 265 8-dimensional observed rainfall). For the theoretical estimates, as the sample size is large, the confidence intervals were computed with the standard errors (the standard deviation of the empirical proportion divided by the square-root of the sample size which is the number of exceedances of \(X_i\)).

The estimated conditional probabilities for the eight multivariate density models are shown in Fig. 15. The pair of nearby stations Barre-des-Cevennes and Cassagnas appear in the top row and the distant pair, Barre-des-Cevennes and Generargues, in the bottom row. In both cases, Barre-des-Cevennes is the conditioning station (\(X_i\) in Eq. (21)). The left column compares the models with Gamma margins and the right column the models with 2-component Log-Normal mixture margins. Therefore, each panel depicts the results for a given pair of stations and for a given marginal model and has thus four curves with vertical error bars for each of the spatial dependence structure. The same acronyms as before are used in the legend: GC and TC for Gaussian and Student t copula and SN and ST for Skew Normal and Skew t. The empirical conditional probabilities are represented with black dots surrounded by their 95 % grey confidence band.

Empirical (black dots) and theoretical (curves) conditional probabilities of exceedances of high thresholds expressed as at-site return levels \(R_i(T)\), see Eq. (21) and Table 2. The x-axis represents the associated return period T. The 95 % confidence band of the empirical estimates is shown in grey while those of the theoretical estimates are the colored vertical bars. In the left (right) column, the models have Gamma (2-component Log-Normal mixture) margins. GC and TC stand for Gaussian and Student t copulas and SN and ST for Skew Normal and Skew t. a Nearby pair Cassagnas |Barre-des-Cevennes: Gamma margins. b Nearby pair Cassagnas |Barre-des-Cevennes: 2-component Log-Normal mixture margins. c Distant pair Generargues |Barre-des-Cevennes: Gamma margins. d Distant pair Generargues |Barre-des-Cevennes: 2-component Log-Normal mixture margins

Given the small sample size, the empirical estimates of the conditional probabilities are unreliable. For the nearby pair, the empirical estimates provide no information for \(T \ge 10\) since the 95 % confidence intervals reach the bounds [0,1], see Fig. 15a, b where the y-axis is truncated. Conversely, for the distant pair, the confidence intervals collapse to 0, also for \(T \ge 10\), see Fig. 15c, d. Indeed, the numbers of exceedances of the conditioning station Barre-des-Cevennes are very low: 21, 8, 5, and 4 exceedances for T = 2, 5, 10 and 20 respectively.

As expected, since this is a monotone transformation, the choice of margins (left column versus right column in Fig. 15) does not affect the ordering of the curves or their global features (rising, declining or stabilizing). However, for the nearby pair, the estimated conditional probabilities are clearly higher with the 2-component Log-Normal mixture margins, see Fig. 15b.

Unsurprisingly, the asymptotically dependent models, t copula (TC) and Student t (ST), yield generally the highest conditional probability estimates. This is especially true for the longer return periods and for the nearby pair, see Fig. 15a, b. In contrast, the Skew Normal model, which is asymptotically independent, provides estimates that are nearly comparable to the asymptotically dependent model estimates for the distant pair, see Fig. 15c, d.

Among the two asymptotically independent models, the Skew Normal model gives higher conditional probability estimates than the Gaussian model. For the nearby pair, the empirical Kendall’s \(\tau\) estimate is of 0.55, and thanks to this strong correlation the Gaussian model is able to predict quite high conditional probabilities as the asymptotic independence property comes into play for much longer return periods. Conversely, for the distant pair that has an empirical Kendall’s \(\tau\) estimated at \(-\)0.067, the Gaussian is almost independent and predicts a conditional probability decreasing very quickly to zero.

5 Discussion and conclusion

We conducted a comparative study of eight multivariate density models (marginal model combined with a dependence structure) for flood-risk rainfall, i.e. rainfall susceptible of causing flash floods in small Mediterranean catchments. The characterization of flood-risk rainfall and in particular, of its spatial variability, is crucial to improve flash-flood understanding. The study area is the Gardon at Anduze, a representative small Mediterranean catchment of about 545 km2. Flood-risk rainfall is defined as rainfall with a high spatial average. For the Gardon at Anduze catchment, spatial average is considered high when it is greater than 50 mm. We used data from eight rain gauge stations at the daily time-step. The pairwise exploratory analysis revealed that the bivariate dependence varies widely from strong for nearby pairs of stations (5 km apart) to weak or zero for distant pairs (40 km apart). This confirms the strong spatial variability of flood-risk rainfall over the catchment.

Two marginal models were considered: the Gamma distribution and a mixture of Log-Normal distributions. The Gamma is a parametric model with 2 parameters that was often used to model the univariate distribution of rainfall. The Log-Normal mixture is a non-parametric model whose complexity, i.e. the number of parameters, can increase with the size of the data set. For all eight stations, two mixture components were selected based on the BIC. As a result, the mixture has 5 parameters, for this data set. Both marginal models are light-tailed, i.e. exponential decay of the upper tail. However, the 2-component Log-Normal mixture has considerably more flexibility due to its larger number of parameters. Such a mixture can adapt, in principle, to more complex distributions caused by the presence of several sub-populations of rainfall.

Four dependence structures with different theoretical properties were included in the comparison: the Gaussian, the Student t, the Skew Normal and the Skew t. The Gaussian is symmetric and asymptotically independent (except when \(|\rho |=1\)). Its parameters are the free parameters of the \(8 \times 8\) correlation matrix (constrained to be symmetric and positive definite), where 8 is the number of rain gauge stations. The Student t is symmetric and asymptotically dependent (except when \(\rho =-1\)). The asymptotic dependence, loosely speaking, characterizes the fact that extremes, i.e. asymptotically high values, tend to occur simultaneously at different sites. The Student t has one additional parameter \(\nu\), compared to the Gaussian, called the degree-of-freedom. This parameter controls the behavior of the tails: the smaller it gets, the greater the asymptotic dependence becomes. The Skew Normal introduces asymmetry in the Gaussian. It has, in addition to the correlation matrix, a vector of skewness parameter \({\varvec{\alpha }} \in {\mathbb {R}}^8\) which define the orientation of the asymmetry, see Fig. 7. The Skew Normal, like its generating distribution, is asymptotically independent but has more flexibility thanks to its eight extra parameters. The Skew t, an asymmetric version of the Student t, combines the properties of the Student t and Skew Normal: it is asymptotically dependent and more flexible than its generating distribution.

The models were included in the comparison either because they were widely used in the literature for similar applications or because they are variants of these models with different theoretical properties (non-parametric, asymmetric, asymptotically dependent). All models are relatively easy to implement thanks to R libraries mentioned throughout the text. The Gaussian with Gamma margins is the most parsimonious model while the Skew t with 2-component Log-Normal margins is the most complex (12 additional parameters). Moreover, we gained reasonable confidence that no multivariate mixture modeling was needed by testing for the number of components in a multivariate Gaussian mixture.

Three types of criteria were taken into account in the comparison of the multivariate density models. First in terms of statistical inference, we sought to evaluate if the marginal and dependence structure models independently provided a reasonable fit. As can be seen from the quantile-quantile plots in Fig. 9, the 2-component Log-Normal mixture, thanks to its greater flexibility, is able to fit all eight stations. Greater flexibility comes with greater variance as indicated by the large confidence intervals for the upper tail of the distribution. In contrast, the Gamma lacks some flexibility as it under-estimates the upper tail of the distribution for four stations, see Fig. 8. Although the four dependence structures all reproduce well the empirical Kendall’s \(\tau\) (see Fig. 10), they might have important differences in the fitted bivariate densities. For instance, the asymmetry of the Skew Normal appears very clearly for the pair of stations Barre-des-Cevennes/Generargues, see Fig. 12. Moreover, the effect of the asymptotic dependence can be seen for the Student t and the Skew t that have greater density in the left-top and bottom-right corners.

Second, model selection was achieved based on the evaluation of the Cramer-Von Mises and the Anderson-Darling statistics with a leave-one-out scheme. With such a scheme, an over-parametrized model is penalized as it will tend to fit too well the calibration sets \({\mathcal {F}}_{k:n-1}\), see Eq. (17), and perform poorly on the left-out observations. Therefore, the leave-one-out evaluation allows a trade-off between goodness-of-fit and complexity. In regard of this quantitative evaluation, the Skew Normal with 2-component Log-Normal mixture margins outperforms significantly the other seven models, see Fig. 13.

Third, to obtain complementary insight into the models, they were compared in terms of two hydrologically interpretable quantities: the return periods of the observed spatial averages and the conditional probability of exceedances of at-site return levels for two representative pairs of stations. In both cases, it is not possible to select a model based on comparisons with the empirical estimates because of the high uncertainty of these rare events. However, inter-model comparisons emphasize some differences between the dependence structures. In particular, the Skew Normal is the only dependence structure providing consistent return periods for the smaller spatial averages, see Fig. 14. In addition, despite being also asymptotically independent, the Skew Normal provides higher conditional probabilities and therefore reveals stronger dependence than the Gaussian, see Fig. 15. For the distant pair of stations, the Skew Normal is almost comparable to the asymptotically dependent models. The Gaussian yields the lowest conditional probabilities and thus is the model with the weakest spatial dependence. In contrast, the Skew t can display very strong spatial dependence, especially for the nearby pair of stations, see Fig. 14.

In conclusion, for the Gardon at Anduze catchment, the Skew Normal with 2-component Log-Normal mixture margins achieved the best fit. The increase in complexity of the mixture model for the margins with respect to the Gamma is compensated by a significant increase in goodness-of-fit. Similarly, the asymmetry introduced by the Skew Normal is an added-value with respect to the Gaussian. In contrast, the asymptotically dependent models did not improve the fit over the asymptotically independent ones. As mentioned in Serinaldi et al. (2014), asymptotic dependence is very difficult to detect when the time series is short, as it is the case in the present work. The Gaussian, which is the benchmark model in this comparison, is not recommended for the data at hand. Even when considering the more complex 2-component Log-Normal mixture model for the margins, its performance remains significantly lower than the Skew Normal. Moreover, preliminary testing lead us to conclude that considering a multivariate mixture of Gaussians, instead of a single Gaussian, would not improve the fit.

The contributions of this work are as follows.

-

1.

The strategy that we adopted to focus on flood-risk rainfall, the type of rainfall associated to flash-floods, allows us to tackle the most important feature multi-site stochastic generators should be able to reproduce when applied to small Mediterranean catchments. This strategy circumvents the need to build a complex stochastic model that must account for rainfall intermittency and inhomogeneity. Homogeneity is dealt with a statistical approach, namely the selection of the number of components in mixture models based on the BIC, rather than by fixing the number of components based on the seasons or the months.

-

2.

We compared multivariate density models of increasing complexity with a different combinations of theoretical properties thanks to the decomposition into marginal and dependence structure models. We were able to determine which properties are most relevant for the data at hand. Multivariate EVT models were not included in the comparison because high dimensional models that could be easily implemented are too simplistic (e.g. Gumbel).

-

3.

We proposed three types of criteria that serve different purposes: (i) statistical inference is meant to asses basic model goodness-of-fit, (ii) model selection serves to identify the best model and (iii) hydrological interpretable quantities helps to gain deeper understanding into the models that could be relevant for hydrological applications.

The perspectives for this work are centered around the development of a spatial stochastic rainfall generator adapted for flood-risk rainfall. A first step would be to study flood-risk rainfall at the hourly time-step. This would be more consistent with the response time of small Mediterranean catchments. As the daily data sets are longer and more complete than hourly data sets, a possible alternative is to rely on temporal disaggregation, such as in Allard and Bourotte (2014). A second step would be to go from a multivariate to a spatial process framework. The multivariate Gaussian extends naturally to the Gaussian process. However, no straightforward extensions to a continuous random process seem available at the moment for the Skew Normal (see Zareifard and Khaledi 2013 and references therein). A possible solution is to rely on the spatial vine copula construction proposed by Gräler (2014). Another issue is to perform the so-called regionalization for the margin parameters, i.e. spatial interpolation, in order to define the margins of a continuous process at every point in space. Finally, it would be interesting to evaluate, in our application, some recent flexible models from multivariate EVT such as those proposed in Salvadori and De Michele (2010) or Bacro et al. (2015) for spatial processes.

References

Ailliot P, Allard D, Monbet V, Naveau P (2015) Stochastic weather generators: an overview of weather type models. J de la Société Française de Stat 156(1):101–113

Allard D, Bourotte M (2014) Disaggregating daily precipitations into hourly values with a transformed censored latent Gaussian process. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess 29(2):453–462

Azzalini A (2013) The skew-normal and related families, vol 3. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Azzalini A (2015) The R package sn: The skew-normal and skew-t distributions (version 1.2-3). Università di Padova, Italia. http://azzalini.stat.unipd.it/SN

Azzalini A, Capitanio A (2003) Distributions generated by perturbation of symmetry with emphasis on a multivariate skew t-distribution. J R Stat Soc 65(2):367–389

Bacro JN, Gaetan C, Toulemonde G (2015) A flexible dependence model for spatial extremes. (in revision)

Barancourt C, Creutin JD, Rivoirard J (1992) A method for delineating and estimating rainfall fields. Water Resour Res 28(4):1133–1144

Bárdossy A, Pegram GGS (2009) Copula based multisite model for daily precipitation simulation. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 13(12):2299–2314

Baxevani A, Lennartsson J (2015) A spatiotemporal precipitation generator based on a censored latent Gaussian field. Water Resour Res

Beirlant J, Goegebeur Y, Segers J, Teugels J (2006) Statistics of extremes: theory and applications. Wiley, New York

Bellone E, Hughes JP, Guttorp P (2000) A hidden Markov model for downscaling synoptic atmospheric patterns to precipitation amounts. Clim Res 15:1–12

Berg D, Aas K (2009) Models for construction of multivariate dependence—a comparison study. Eur J Financ 15(7):639–659

Blanchet J, Davison AC (2011) Spatial modeling of extreme snow depth. Ann Appl Stat 5:1699–1725

Borga M, Anagnostou EN, Blöschl G, Creutin JD (2011) Flash flood forecasting, warning and risk management: the HYDRATE project. Environ Sci Policy 14 (7):834–844. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2011.05.017. ISSN 1462-9011. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1462901111000943. Adapting to Climate Change: Reducing Water-related Risks in Europe

Bortot P (2010) Tail dependence in bivariate skew-normal and skew-t distributions. Available online: www2.stat.unibo.it/bortot/ricerca/paper-sn-2.pdf

Bouvier C, Cisneros L, Dominguez R, Laborde J-P, Lebel T (2003) Generating rainfall fields using principal components (PC) decomposition of the covariance matrix: a case study in Mexico city. J Hydrol 278(1):107–120

Bouvier C, Ayral PA, Brunet P, Crespy A, Marchandise A, Martin C (2007) Recent advances in rainfall-runoff modelling: extrapolation to extreme floods in southern France. In: First international workshop on hydrological extremes. Observing and modelling exceptional floods and rainfalls, pp 229–238, Cosenza. FRIEND-AMHY

Braud I, Ayral PA, Bouvier C, Branger F, Delrieu G, Le JC, Nord G, Vandervaere JP, Anquetin S, Adamovic M, Andrieu J, Batiot C, Boudevillain B, Brunet P, Carreau J, Confoland A, Didon-Lescot JF, Domergue JM, Douvinet J, Dramais G, Freydier R, Gérard S, Huza J, Leblois E, Le OB, Le RB, Marchand P, Martin P, Nottale L, Patris N, Renard B, Seidel JL, Taupin JD, Vannier O, Vincendon B, Wijbrans A (2014) Multi-scale hydrometeorological observation and modelling for flash flood understanding. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 18 (9): 3733–3761. doi:10.5194/hess-18-3733-2014. http://www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/18/3733/2014/

Carreau J, Bengio Y (2009) A hybrid Pareto model for asymmetric fat-tailed data: the univariate case. Extremes 12(1):53–76

Carreau J, Vrac M (2011) Stochastic downscaling of precipitation with neural network conditional mixture models. Water Resour Res 47(10)

Carreau J, Neppel L, Arnaud P, Cantet P (2013) Extreme rainfall analysis at ungauged sites in the South of France: comparison of three approaches. J de la Société Française de Stat 154(2):119–138

Ceresetti D, Ursu E, Carreau J, Anquetin S, Creutin J-D, Gardes L, Girard S, Molinie G (2012) Evaluation of classical spatial-analysis schemes of extreme rainfall. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 12:3229–3240

Chandler RE, Wheater HS (2002) Analysis of rainfall variability using generalized linear models: a case study from the west of Ireland. Water Resour Res 38(10):10

Cleveland WS (1981) LOWESS : a program for smoothing scatterplots by robust locally weighted regression. Am Stat 35:54

Coles S (2001) An introduction to statistical modeling of extreme values., Springer series in statisticsSpringer, New York

Coles S, Heffernan J, Tawn J (1999) Dependence measures for extreme value analyses. Extremes 2(4):339–365

Delrieu G, Nicol J, Yates E, Kirstetter P-E, Creutin J-D, Anquetin S, Obled C, Saulnier G-M, Ducrocq V, Gaume E, Payrastre O, Andrieu H, Ayral P-A, Bouvier C, Neppel L, Livet M, Lang M, du Châtelet JP, Walpersdorf A, Wobrock W (2005) The catastrophic flash-flood event of 8–9 september 2002 in the Gard region, France: a first case study for the Cévennes-Vivarais Mediterranean Hydrometeorological Observatory. J Hydrometeorol 6(1):34–52

Demarta S, McNeil AJ (2005) The t copula and related copulas. Int Stat Rev 73(1):111–129

Ducrocq V, Nuissier O, Ricard D, Lebeaupin C, Thouvenin T (2008) A numerical study of three catastrophic precipitating events over southern France. II: mesoscale triggering and stationarity factors. Q J R Meteorol Soc 134(630):131–145

Dupuis DJ, Tawn JA (2001) Effects of mis-specification in bivariate extreme value problems. Extremes 4(4):315–330

Dupuis DJ (2007) Using copulas in hydrology: benefits, cautions, and issues. J Hydrol Eng 12(4):381–393

Embrechts P, McNeil A, Straumann D (2002) Correlation and dependence in risk management: properties and pitfalls. Risk Manag, pp 176–223

Flecher C, Naveau P, Allard D, Brisson N (2010) A stochastic daily weather generator for skewed data. Water Resour Res 46(7)

Frayler C, Raftery AE (1999) MCLUST: software for model-based cluster analysis. J Classif 16:297–306

Garavaglia F, Gailhard J, Paquet E, Lang M, Garçon R, Bernardara P (2010) Introducing a rainfall compound distribution model based on weather patterns sub-sampling. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci Discuss 14:951

Gardes L, Girard S (2010) Conditional extremes from heavy-tailed distributions: an application to the estimation of extreme rainfall return levels. Extremes 13(2):177–204

Gaume E, Bain V, Bernardara P, Newinger O, Barbuc M, Bateman A, Blaškovičová L, Blöschl G, Borga M, Dumitrescu A et al (2009) A compilation of data on European flash floods. J Hydrol 367(1):70–78

Genest C, Favre A-C (2007) Everything you always wanted to know about copula modeling but were afraid to ask. J Hydrol Eng 12(4):347–368

Genest C, Huang W, Dufour J-M (2013) A regularized goodness-of-fit test for copulas. J de la Société Française de Statistique & revue de statistique appliquée 154(1):64–77

Gilleland E, Katz RW (2011) New software to analyze how extremes change over time. EOS, Trans Am Geophys Union 92(2):13–14

Gräler B (2014) Modelling skewed spatial random fields through the spatial vine copula. Spat Stat 10:87–102

Guillot G, Lebel T (1999) Approximation of Sahelian rainfall fields with meta-gaussian random functions. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess 13(1–2):113–130

Hughes JP, Guttorp P, Charles SP (1999) A non-homogeneous hidden markov model for precipitation occurrence. Appl Stat 48:15–30

Joe H (1997) Multivariate models and multivariate dependence concepts, vol 73. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Kleiber W, Katz RW, Rajagopalan B (2012) Daily spatiotemporal precipitation simulation using latent and transformed Gaussian processes. Water Resour Res 48(1):1

Kojadinovic I, Yan J (2010) Modeling multivariate distributions with continuous margins using the copula R package. J Stat Softw 34 (9): 1–20. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v34/i09/

Kollo T, Selart A, Visk H (2013) From multivariate skewed distributions to copulas. In: Combinatorial matrix theory and generalized inverses of matrices. Springer, New York, pp 63–72

Lebel T, Laborde JP (1988) A geostatistical approach for areal rainfall statistics assessment. Stoch Hydrol Hydraul 2(4):245–261

Leblois E, Creutin JD (2013) Space-time simulation of intermittent rainfall with prescribed advection field: adaptation of the turning band method. Water Resour Res, pp n/a–n/a. ISSN 1944-7973. doi:10.1002/wrcr.20190

Lennartsson J, Baxevani A, Chen D (2008) Modelling precipitation in Sweden using multiple step markov chains and a composite model. J Hydrol 363(1):42–59

Li C, Singh VP, Mishra AK (2012) Simulation of the entire range of daily precipitation using a hybrid probability distribution. Water Resour Res 48(3)