Abstract

Background

Understanding disparities in pediatric kidney transplants is important to provide equitable care. We compared transplant outcomes between English-speaking (ES) and interpreter-needing (IN) pediatric kidney transplant recipients.

Methods

Through retrospective review, primary kidney transplant recipients, 0–21 years transplanted between 2005 and 2019, were divided into ES and IN cohorts. Continuous and categorical variables were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum, Welch two-sample t-test, and chi-squared analyses. Patient survival, graft survival, and rejection-free survival were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier methods and Cox regression. Days hospitalized were evaluated using negative binomial regression.

Results

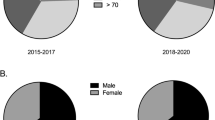

Our sample included 211 ES and 37 IN transplant recipients. Compared with the ES, the IN cohort was older at transplant (14.56 vs. 11.03 years; p < 0.01), had more time between kidney failure and transplant (0.9 vs. 0.3 years; p < 0.01), and more often received deceased over living donor transplants (78.4% vs. 30.4%; p < 0.01). Multivariate Cox proportional-hazard models evaluating adjusted 5-year patient survival demonstrated decreased 5-year post-transplant survival in the IN cohort (aHR = 10.10, 95% CI: 1.5, 66.8; p = 0.02). We did not identify differences in 5-year death-censored graft survival (aHR = 0.57; 95% CI: 0.14, 2.4; p = 0.4) nor rejection-free survival (aHR = 0.8; 95% CI: 0.4, 1.5; p = 0.5). We found significantly fewer hospitalization events in the IN cohort during the first year post-transplant (aRR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.4, 0.9; p = 0.01) but no difference 5-year post-transplant. The IN cohort had more missed outpatient appointments (10.4% vs. 2.8%; p = 0.03) and undetectable serum immunosuppressant levels (mean: 3.8% vs. 1.3%; p = 0.02) 5 years post-transplant.

Conclusions

Pediatric kidney transplant recipients requiring interpreter services for healthcare delivery demonstrate fewer post-transplant interactions with their healthcare team (fewer hospitalizations and more no-show visits) and lower 5-year patient survival compared with recipients not requiring interpreters.

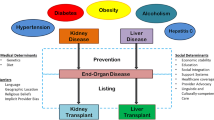

Graphical abstract

A higher resolution version of the Graphical abstract is available as Supplementary information

Similar content being viewed by others

References

United Nations Platform on Social Determinants of Health (2016) Health in the post-2015 development agenda: need for a social determinants of health approach. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/health-in-the-post-2015-development-agenda-need-for-a-social-determinants-of-health-approach. Accessed 30 May 2022

Gitterman BA, Flanagan PJ, Cotton WH, Dilley KJ, Duffee JH, Green AE, Keane VA, Krugman SD, Linton JM, McKelvey CD, Nelson JL, Council of Community Pediatrics (2016) Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics 137:e20160339. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0339

Stevens MA, Beebe TJ, Wi CI, Taler SJ, St Sauver JL, Juhn YJ (2020) HOUSES index as an innovative socioeconomic measure predicts graft failure among kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation 104:2383–2392. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000003131

Hensley CG, Real FJ, Walsh KE, Klein MD, Beck AF (2018) Tackling the social determinants of health: a critical component of safe and effective healthcare. Pediatr Qual Saf 3:e054. https://doi.org/10.1097/pq9.0000000000000054

Cohen AL, Rivara F, Marcuse EK, McPhillips H, Davis R (2005) Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients? Pediatrics 116:575–579. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0521

Flores G (2014) Families facing language barriers in healthcare: when will policy catch up with the demographics and evidence. J Pediatr 164:1261–1264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.02.033

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics (2021) America’s children: key national indicators of well-being. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.childstats.gov/pdf/ac2021/ac_21.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2022

Civil Rights Act § 6, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d et seq (1964)

Exec. Order No. 13166, 65 Fed. Reg. 50121 (Aug 11, 2000)

Boylen S, Cherian S, Gill F, Leslie G, Wilson S (2020) Impact of professional interpreters on outcomes for hospitalized children from migrant and refugee families with limited English proficiency: a systematic review. JBI Evid Synth 18:1360–1388. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00300

Fields A, Abraham M, Gaughan J, Haines C, Sarah Hoehn K (2016) Language matters: race, trust, and outcomes in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 32:222–226. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000453

Steinberg EM, Valenzuela-Araujo D, Zickafoose JS, Kieffer E, DeCamp LR (2016) The “battle” of managing language barriers in health care. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 55:1318–1327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922816629760

Hampers LC, Cha S, Gutglass DJ, Binns HJ, Krug SE (1999) Language barriers and resource utilization in pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics 103:1253–1256. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.103.6.1253

Khan A, Yin H, Brach C, Graham D, Ramotar M, Williams D, Spector N, Landrigan C, Dreyer B (2020) Association between parent comfort with English and adverse events among hospitalized children. JAMA Pediatr 174:e203215. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3215

de Jong RW, Stel VS, Heaf JG, Murphy M, Massy ZA, Jagger KJ (2021) Non-medical barriers reported by nephrologists when providing renal replacement therapy or comprehensive conservative management to end-stage kidney disease patients: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 36:848–862. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz271

Cervantes L, Jones J, Linas S, Fischer S (2017) Qualitative interviews exploring palliative care perspectives of Latinos on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12:788–798. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.10260916

Talamantes E, Norris KC, Mangione CM, Moreno G, Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Bunnapradist S, Huang E (2017) Linguistic isolation and access to the active kidney transplant waiting list in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12:483–492. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.07150716

Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, Mak RH, Kaskel F, Warady BA, Furth SL (2009) New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 20:629–637. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2008030287

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) (2009) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150:604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006

Robles JA, Troy JD, Schroeder KM, Martin PL, LeBlanc TW (2021) Parental limited English proficiency in pediatric stem cell transplantation: clinical impact and healthcare utilization. Pediatr Blood Cancer 68:e29174. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.29174

Chinnakotla S, Verghese P, Chavers B, Rheault MN, Kirchner V, Dunn T, Kashtan C, Nevins T, Mauer M, Pruett T, MNUM Pediatric Transplant Program (2017) Outcomes and risk factors for graft loss: lessons learned from 1,056 pediatric kidney transplants at the University of Minnesota. J Am Coll Surg 224:473–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.12.027

Ashoor IF, Dharnidharka VR (2019) Non-immunologic allograft loss in pediatric kidney transplant recipients. Pediatr Nephrol 34:211–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-018-3908-4

Dobbels F, Ruppar T, De Geest S, Decorte A, Van Damme-Lombaerts R, Fine RN (2010) Adherence to the immunosuppressive regimen in pediatric kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review. Pediatr Transplant 14:603–613. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01299.x

Freeman MA, Myaskovsky L (2015) An overview of disparities and interventions in pediatric kidney transplantation worldwide. Pediatr Nephrol 30:1077–1086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-014-2879-3

Mohamed M, Soliman K, Pullalarevu R, Kamel M, Srinivas T, Taber D, Posadas Salas MA (2021) Non-adherence to appointments is a strong predictor of medication non-adherence and outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Med Sci 362:381–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms.2021.05.011

Taber DJ, Fleming JN, Fominaya CE, Gebregziabher M, Hunt KJ, Srinivas TR, Baliga PK, McGillicuddy JW, Egede LE (2017) The impact of health care appointment non-adherence on graft outcomes in kidney transplantation. Am J Nephrol 45:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1159/000453554

Dunlap JL, Jaramillo JD, Koppolu R, Wright R, Mendoza F, Bruzoni M (2015) The effects of language concordant care on patient satisfaction and clinical understanding for Hispanic pediatric surgery patients. J Pediatr Surg 50:1586–1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.12.020

Schenker Y, Karter AJ, Schillinger D, Warton EM, Alder NE, Moffet HH, Ahmed AT, Fernandez A (2010) The impact of limited English proficiency and physician language concordance on reports of clinical interactions among patients with diabetes: the DISTANCE study. Patient Educ Couns 81:222–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.02.005

Ortega P, Pérez N, Robles B, Turmelle Y, Acosta D (2019) Teaching medical Spanish to improve population health: evidence for incorporating language education and assessment in U.S. medical schools. Health Equity 3:557–566. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2019.0028

Patzer RE, Amaral S, Klein M, Kutner N, Perryman JP, Gazmararian JA, McClellan WM (2012) Racial disparities in pediatric access to kidney transplantation: does socioeconomic status play a role? Am J Transplant 12:369–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03888.x

Ortega P, Shin TM, Martínez GA (2021) Rethinking the term “limited English proficiency” to improve language-appropriate healthcare for all. J Immigr Minor Health 24:799–805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01257-w

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Houachee Lee and Dr. Maribet McCarty for their consulting services while compiling the data for this study. Additionally, we are grateful for the support of the MHealth Fairview analytics consulting team.

Funding

This work was, in part, supported by the Cancer Biology Training Grant of the University of Minnesota (T32 CA009138; C.P.K.), Medical Scientist Training Program (T32 GM008244; C.P.K.), and the F30 CA228261 (C.P.K.). This research was also supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR002494.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kerkvliet, S.P., Perez Kerkvliet, C.J., Jiang, Z. et al. Language barriers and kidney transplantation in children. Pediatr Nephrol 38, 2209–2219 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-022-05821-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-022-05821-w