Abstract

Background

In pediatric patients treated with levamisole to prevent relapses of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (INS), a transient and non-progressive rise in creatinine levels has been observed. It has been suggested that levamisole affects tubular secretion of creatinine. However, other potential mechanisms — nephrotoxicity and interference with the analytical assay for creatinine — have never been thoroughly investigated.

Methods

In three steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome (SSNS) patients with elevated plasma creatinine levels, treated with levamisole 2.5 mg/kg every other day, serum cystatin C was determined. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated using the full age spectrum for creatinine and the full age spectrum for cystatin C equations. Interference of levamisole with the enzymatic creatinine assay was tested using spare human plasma of different creatinine concentrations spiked with levamisole (4, 20, and 100 µM).

Results

Three patients who received levamisole with elevated plasma creatinine levels had normal serum cystatin C levels and corresponding estimated GFR. There was no assay interference.

Conclusion

Levamisole increases plasma creatinine levels, which is most probably due to impaired tubular secretion of creatinine since there was no assay interference and patients had normal eGFR based on serum cystatin C. However, interference of metabolites of levamisole could not be excluded. To monitor GFR, cystatin C in addition to creatinine should be used and be measured before and during levamisole use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Levamisole has been increasingly used as a steroid-sparing agent in steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome (SSNS) in children. Although the exact mechanism of action in SSNS is still unclear, it is believed that it has immunomodulatory properties. Recent studies in children with frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome (FRNS) or steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome (SDNS) showed that levamisole is efficacious and safe to prevent relapses [1], even when administered on a daily basis [2]. In children, side effects are relatively uncommon and include leukopenia (3.7%), gastrointestinal upset (2.4%), and skin rash (1.5%), which are reversible after discontinuation of the treatment [3]. Additionally, ANCA positivity has been observed in up to 20% of children using levamisole [4].

Recently, Hoogenboom et al. described elevated plasma creatinine levels and a corresponding decrease in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculated by the Schwartz equation [5] during levamisole treatment in a cohort of children with FRNS or SDNS [6]. This decrease in eGFR was not progressive and normalized after levamisole was discontinued. The authors speculated that levamisole might interfere with tubular handling of creatinine resulting in a rise in creatinine levels independent of GFR. Other potential mechanisms considered were interference of levamisole with the analytical assay for creatinine or transient nephrotoxicity.

In our hospital, levamisole has been extensively used for the prevention of relapses of SSNS. A similar trend of transient elevated plasma creatinine levels has been observed. In this report, we provide additional proof that the rise in plasma creatinine is indeed the result of levamisole-induced decreased tubular creatinine secretion, rather than assay interference or impaired kidney function.

Methods

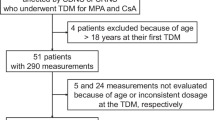

This study was conducted at the department of pediatric nephrology of Emma Children’s Hospital, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. All SSNS patients aged between 2 and 18 years who participated in the LEARNS study were screened for the use of levamisole for the prevention of relapses and documented creatinine and at least one cystatin C (cysC) measurements. The LEARNS study is an international, randomized, placebo-controlled trial investigating the efficacy and safety of adding levamisole to corticosteroids for the prevention of relapses of the first episode of INS [7]. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Amsterdam UMC, location AMC. Screened patients used levamisole in an open-label fashion after a relapse occurred. Relapses were treated according to the GPN protocol: 60 mg/m2/day until remission, followed by 40 mg/m2/alternate day for 4 weeks. After remission was achieved, levamisole (2.5 mg/kg every other day, maximum of 150 mg/dose) was initiated. A treatment duration of 12 months was intended. Reasons to discontinue levamisole included relapse, marked side effects, and prolonged remission (> 12 months). Estimated GFR was calculated from plasma creatinine or serum cysC using the age-based full age spectrum (FAS) equations [8].

Plasma creatinine concentrations were determined by a standardized enzymatic colorimetric method (Creatinine plus ver.2; Roche diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) using the Cobas 8000 c702 module (Roche diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Serum cysC concentrations were determined by particle-enhanced immunonephelometry (N Latex Cystatin C; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) using the Atellica NEPH630 System (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany).

To test the interference of levamisole with the creatinine analytical enzymatic assay, spare human blood samples from 9 adult patients with low (26–33 µmol/L) and high (105–108 µmol/L) plasma creatinine concentrations were spiked with increasing levamisole concentrations. Concentrations of 0, 4, 20, and 100 µM were obtained by diluting 200 mM levamisole stock solution with NaCl. All experiments were done at the Department of Clinical Chemistry of Amsterdam UMC, location VUmc.

Results

Patient presentation

Chart analysis identified six patients who received levamisole and in whom plasma creatinine and the corresponding eGFR were determined at every visit between 2018 and 2021. In all patients, plasma creatinine increased during treatment (data not shown). However, cysC had been measured at least once in three patients. CysC was determined in response to elevated plasma creatinine levels at the next visit and was only determined during levamisole treatment.

Patient 1 (female, age 6 years) received levamisole for 64 weeks during which she remained in remission. After 4 weeks, creatinine rose and remained stable between 50 and 55 µmol/L (FAScreat around 90 mL/min/1.73 m2, while cysC was at 0.80 mg/L (FAScys 101 mL/min/1.73 m2). When levamisole was discontinued, plasma creatinine decreased to 39 µmol/L. However, the patient experienced a new series of relapses and levamisole was started again. Four weeks after restart, plasma creatinine rose from 40 to 56 µmol/L, again with normal cysC levels (0.79 mg/L) and corresponding FAScys (116 mL/min/1.73 m2) (Fig. 1a).

a–c Graphical display of the evolution of plasma creatinine and eGFR for three different patients. The colored solid lines represent the change in plasma creatinine concentrations (left y-axis) during the course of levamisole treatment, while the dashed blue lines represent the FAScreat and the black dots show the FAScys (right y-axis). The vertical dashed line indicates the start of levamisole treatment, the horizontal dashed line indicates the cut-off value for impaired kidney function (90 mL/min/1.73 m2; right y-axis). In patient 1 (a), levamisole was restarted when she experienced a second relapse after discontinuation of levamisole. d Presentation of the measured plasma creatinine concentration by the enzymatic assay for low and high concentrations of levamisole

In patient 2 (male, age 5 years), creatinine had risen from 38 to 49 µmol/L within 3 weeks after introduction of levamisole and continued to rise to a maximum of 69 µmol/L. When FAScreat had dropped to 78 mL/min/1.73 m2, cysC was determined at 0.89 mg/L, corresponding to a FAScys of 102 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Fig. 1b). Therefore, levamisole was continued.

Patient 3 (male, age 5 years) was in partial remission when levamisole was started. Prednisolone was gradually tapered over the course of levamisole treatment. Before the start of levamisole, creatinine had been 22 µmol/L, but increased to 36 µmol/L and 42 µmol/L after 4 and 14 weeks, respectively. During levamisole treatment, FAScreat (101 mL/min/m2) and FAScys (125 mL/min/m2) remained above the threshold for impaired kidney function (Fig. 1c).

Assay interference

There was no interference of levamisole with the enzymatic creatinine assay. With increasing levamisole concentrations, serum creatinine concentrations did not deviate from baseline measurements, with low and high plasma creatinine concentrations showing minimal deviations up to 4% and 2.8%, respectively (Fig. 1d).

Discussion

In line with Hoogenboom et al. [6], we observed an increase in plasma creatinine levels in three children during levamisole treatment. Yet, this was not associated with an impaired eGFR when calculated from cysC levels. When levamisole was discontinued, creatinine levels returned to normal. Additionally, levamisole did not interfere with the analytical enzymatic assay for creatinine in plasma.

Three potential mechanisms for the elevated serum creatinine were considered: (1) nephrotoxicity, (2) interference with the analytical assay, and (3) impaired tubular secretion. Hoogenboom et al. considered nephrotoxicity of levamisole unlikely as the rise in plasma creatinine was not progressive and independent of dose and duration of treatment. This is supported by our finding that, based on cysC levels, eGFR was not impaired in our three patients. In line with these findings, inulin clearance did not change in a study in dogs treated with levamisole [9].

To our knowledge, this is the first study that shows that levamisole does not interfere with the enzymatic assay to measure creatinine in plasma, not even at supra-physiological concentrations. In a study in children receiving alternate day levamisole, the Cmax was 438 ng/mL (2.36 µM) [10]. Particularly, there was no change at low and high creatinine concentrations. As children with INS are young (peak incidence 2–6 years) and have a normal kidney function, reference intervals for creatinine concentrations lie between 18 and 54 µmol/L [11]. However, levamisole has a short half-life of 2.6 h [10] and potential assay interference with one of its metabolites, i.e., aminorex and p-hydroxylevamisole, cannot be excluded. Having eliminated nephrotoxicity and — presumably — assay interference as potential mechanisms of creatinine elevation by levamisole, interference with the tubular secretion of creatinine remains as the most probable explanation.

Creatinine has a low molecular weight (113 Da), is not protein-bound, and is freely filtered across the glomerular basement membrane. Although chiefly considered a marker for GFR, creatinine is also excreted by the renal tubules [12]. Tubular secretion is variable and its rate is inversely related to GFR. It can be inhibited by a number of drugs through inhibition of organic cation transporters (OCTs), of which cimetidine, trimethoprim, and fenofibrate are well-known. There is limited evidence whether levamisole is an OCT inhibitor: one study found an inhibitory effect on the rOCT1 in rat hepatocytes [13]. However, whether this OCT is present in humans is uncertain.

CysC is a low-molecular weight protein (13 kDa), which has evolved as an alternative to plasma creatinine for the monitoring of kidney function [12]. Serum cysC concentrations are inversely related to GFR. CysC is produced at a constant rate by nearly all nucleated cells. Like other low-molecular weight proteins, it is freely filtered across the glomerular membrane and almost entirely reabsorbed and metabolized in the proximal tubule. Therefore, only trace amounts can be found in the urine. There are no indications that cysC is secreted in the kidney tubule; still, there is some breakdown in the liver, which is relevant in severe kidney failure only and has not been linked to any drug therapy [14]. A relevant interaction in the setting of INS is high-dose glucocorticoid treatment, since this increases cysC synthesis and results in an underestimation of GFR [15].

In conclusion, our findings support the concept that levamisole increases plasma creatinine by interfering with the tubular secretion of creatinine and argue against nephrotoxicity and assay interference. Although an increased plasma creatinine level in children using levamisole should not prompt clinical concern, we recommend using additional cysC-based equations to confirm normal kidney function. In case of decreased creatinine-based eGFR and in the absence of an abnormal cysC-based eGFR, levamisole should not be discontinued.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The R and GraphPad syntaxes used for the development of the graphs are available upon request.

Change history

28 June 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-022-05622-1

References

Gruppen MP, Bouts AH, Jansen-van der Weide MC, Merkus MP, Zurowska A, Maternik M, Massella L, Emma F, Niaudet P, Cornelissen EAM, Schurmans T, Raes A, van de Walle J, van Dyck M, Gulati A, Bagga A, Davin JC (2018) A randomized clinical trial indicates that levamisole increases the time to relapse in children with steroid-sensitive idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int 93:375–389

Abeyagunawardena AS, Karunadasa U, Jayaweera H, Thalgahagoda S, Tennakoon S, Abeyagunawardena S (2017) Efficacy of higher-dose levamisole in maintaining remission in steroid-dependant nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 32:1363–1367

Mühlig AK, Lee JY, Kemper MJ, Kronbichler A, Yang JW, Lee JM, Shin JI, Oh J (2019) Levamisole in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: clinical efficacy and pathophysiological aspects. J Clin Med 8:860–860

Krischock L, Pannila P, Kennedy SE (2021) Levamisole and ANCA positivity in childhood nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 36:1795–1802

Schwartz GJ, Schneider MF, Maier PS, Moxey-Mims M, Dharnidharka VR, Warady BA, Furth SL, Mũoz A (2012) Improved equations estimating GFR in children with chronic kidney disease using an immunonephelometric determination of cystatin C. Kidney Int 82:445–453

Hoogenboom LA, Webb H, Tullus K, Waters A (2021) The effect of levamisole on kidney function in children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 36:3799–3802

Veltkamp F, Khan DH, Reefman C, Veissi S, Van Oers HA, Levtchenko E, Mathôt RAA, Florquin S, Van Wijk JAE, Schreuder MF, Haverman L, Bouts AHM (2019) Prevention of relapses with levamisole as adjuvant therapy in children with a first episode of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: Study protocol for a double blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial (the LEARNS study). BMJ Open 9:e027011

Pottel H, Delanaye P, Schaeffner E, Dubourg L, Eriksen BO, Melsom T, Lamb EJ, Rule AD, Turner ST, Glassock RJ, De Souza V, Selistre L, Goffin K, Pauwels S, Mariat C, Flamant M, Ebert N (2017) Estimating glomerular filtration rate for the full age spectrum from serum creatinine and cystatin C. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32:497–507

Plante GE, Erian R, Petitclerc C (1981) Excretion of levamisole. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 216:617–623

Kreeftmeijer-Vegter AR, Dorlo TPC, Gruppen MP, De Boer A, De Vries PJ (2015) Population pharmacokinetics of levamisole in children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Br J Clin Pharmacol 80:242–252

Colantino DA, Kyriakopoulou L, Chan MK, Daly CH, Brinc D, Venner AA, Pasic MD, Armbruster D, Adeli K (2012) Closing the gaps in pediatric laboratory reference intervals: a CALIPER database of 40 biochemical markers in a healthy and multiethnic population of children. Clin Chem 58:854–868

den Bakker E, Gemke RJBJ, Bökenkamp A (2018) Endogenous markers for kidney function in children: a review. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 55:163–183

Martel F, Ribeiro L, Calhau C, Azevedo I (1999) Inhibition by levamisole of the organic cation transporter rOCT1 in cultured rat hepatocytes. Pharmacol Res 40:275–279

Slort PR, Ozden N, Pape L, Offner G, Tromp WF, Wilhelm AJ, Bökenkamp A (2012) Comparing cystatin C and creatinine in the diagnosis of pediatric acute renal allograft dysfunction. Pediatr Nephrol 27:843–849

Bökenkamp A, Laarman CARC, Braam KI, van Wijk JAE, Kors WA, Kool M, Valk Jd, Bouman AA, Spreeuwenberg MD, Stoffel-Wagner B (2007) Effect of corticosteroid therapy on low-molecular-weight protein markers of kidney function. Clin Chem 53:2219–2221

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank G.H. Khan for preparing and providing the levamisole stock solution. The LEARNS study is an interuniversity collaboration in the Netherlands that is established to perform a double blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial on the efficacy of levamisole on relapses in children with a first episode of steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome, and to study basic mechanisms underlying nephrotic syndrome and the mode of action of levamisole. Principal investigators are (in alphabetical order): A.H.M. Bouts (Department of Pediatric Nephrology, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), S. Florquin (Department of Pathology, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), J.E. Guikema (Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), L. Haverman (Psychosocial Department, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), L.P.W.J. van den Heuvel (Radboud Institute for Molecular Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands), E. Levtchenko (Department of Pediatric Nephrology, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium), R.A.A. Mathôt (Department of Hospital Pharmacy, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), M.F. Schreuder (Department of Pediatric Nephrology, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands), B. Smeets (Radboud Institute for Molecular Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands ), and J.A.E. van Wijk (Department of Pediatric Nephrology, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands).

Funding

F.V. and A.H.M. are supported by a consortium grant from the Dutch Kidney Foundation (CP16.03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

FV drafted the concept of this study, collected and analysed the data, and drafted the first manuscript. JS and HH designed and performed the experiments, interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. HH designed the experiments and critically reviewed the manuscript. AB drafted the concept of this study and critically reviewed the manuscript. AHB consulted patients, drafted the concept of this study, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All patients described in this study are participants in the LEARNS study. The LEARNS study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands (2017_310).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent has been obtained from the parents and/or patients (if applicable).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent has been obtained from the parents and/or patients (if applicable).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: During the process of typesetting, the institutional author attribution “on behalf of the LEARNS consortium” was left out of the author group. The original article has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Veltkamp, F., Bökenkamp, A., Slaats, J. et al. Levamisole causes a transient increase in plasma creatinine levels but does not affect kidney function based on cystatin C. Pediatr Nephrol 37, 2515–2519 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-022-05547-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-022-05547-9