Abstract

Background

During the initial COVID-19 pandemic, young United Kingdom (UK) kidney patients underwent lockdown and those with increased vulnerabilities socially isolated or ‘shielded’ at home. The experiences, information needs, decision-making and support needs of children and young adult (CYA) patients or their parents during this period is not well known.

Methods

A UK-wide online survey co-produced with patients was conducted in May 2020 amongst CYA aged 12–30, or parents of children aged < 18 years with any long-term kidney condition. Participants answered qualitative open text alongside quantitative closed questions. Thematic content analysis using a three-stage coding process was conducted.

Results

One-hundred and eighteen CYA (median age 21) and 197 parents of children (median age 10) responded. Predominant concerns from CYA were heightened vigilance about viral (68%) and kidney symptoms (77%) and detrimental impact on education or work opportunities (70%). Parents feared the virus more than CYA (71% vs. 40%), and had concerns that their child would catch the virus from them (64%) and would have an adverse impact on other children at home (65%). CYA thematic analysis revealed strong belief of becoming seriously ill if they contracted COVID-19; lost educational opportunities, socialisation and career development; and frustration with the public for not following social distancing rules. Positive outcomes included improved family relationships and community cohesion. Only a minority (14–21% CYA and 20–31% parents, merged questions) desired more support. Subgroup analysis identified greater negative psychological impact in the shielded group.

Conclusions

This survey demonstrates substantial concern and need for accurate tailored advice for CYA based on individualised risks to improve shared decision making.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

On 23 March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK entered a continuous period of ‘lockdown’, with closure of schools, workplaces and restrictions on outdoor movements other than exercise or essential shopping. Studies into the experiences of families under quarantine for previous pandemics (SARS-CoV-1, MERS) and in Chinese adolescents during COVID-19 showed very high levels of traumatic distress [1, 2]. Prior to the current pandemic, children and young adults (CYA) with chronic kidney diseases (CKD) already had well-established psycho-social vulnerabilities; most studies reported a greater rate of social and behavioural problems with adjustment disorders, depression, anxiety and neurocognitive disorders compared to their peers [3,4,5]. They were less likely to be in a relationship, more likely to live in the family home, receive no income, be unable to work due to ill-health and have worse well-being than peers in the general population [6, 7].

Early during the UK epidemic, the government issued a list of conditions and associated treatment regimens considered to constitute extreme clinical vulnerability to COVID-19 disease [8]. For kidney patients, regardless of age, these initially included those requiring dialysis, or on immunosuppression, e.g. kidney transplant recipients and non-transplant indications at an arbitrary level which changed several times during the pandemic. They were recommended to ‘shield’, i.e. to remain at home at all times, and have no face-to-face contact with anyone outside of their household [9].

During this period of prolonged lockdown, it became evident that the potential harms of COVID-19 (the disease caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2) to CYA even with severe co-morbidities were not only from the virus itself but also from being kept at home and away from friends, education or fledgling careers [1]. Fortunately, in stark contrast to the devastating 31% mortality rate in the over 40-year age kidney transplant recipients, there were no deaths reported in under 40-year-olds [10]. The impact of missing education in CYA with CKD who already have lower cognition compared with the general population is unknown, and there is also significant concern about the gaps in safeguarding protection when vulnerable children are not visible to teachers [11, 12].

Little is known about the concerns and decision-making in this young patient group, especially given the rapidly evolving instructions in the early stages of the pandemic. Existing professional networks of charities, clinicians, academics, parents, young patients and young adults were mobilised to develop this study with the aims of increasing our understanding of the evolving experiences, information needs and decision-making in CYA and parents of children living with a kidney condition.

Methods

Study design

A survey of CYA with a kidney condition (12–30 years) and parents with children aged 0–18 years who have kidney conditions, assessing experiences, information and support needs and decision-making was undertaken. The survey was co-produced in its design, piloting and dissemination by CYA, parents, clinicians, youth workers and patient advocacy groups. Due to time pressure and socially distancing regulations, CYA representatives were recruited from personal contacts and video focus groups held to refine survey questions before dissemination.

The survey opened between 11 May and 1 June 2020, during the initial wave (including lockdown) of the COVID-19 pandemic within the UK. On 1 June we closed the survey to coincide with the first significant UK easing of lockdown reopening schools and permitting people to meet outdoors. The study was approved by University of Southampton and UK NHS Health Research Authority Research Ethics Committees (IRAS nr. 282176).

Whilst SARS-CoV-2 refers to the virus and COVID-19 refers to the clinical disease, during co-design, we found that this distinction was not appreciated by many non-medical people. For this reason, the questionnaires referred to COVID-19 to cover the virus and the disease. For convenience, the term is used in this way throughout the paper.

Participants

Participants were CYA who self-identified they were affected ‘with any long-term kidney condition’ aged between 12 and 30 years, or parents/guardian of a child aged between 0 and 18 years, able to read and respond in English. Participants were recruited from across the UK by healthcare teams, national kidney charities, targeted closed Facebook groups and social media. The survey was available either as a link or via poster QR code accessible on a PC, tablet or smartphone. Electronic consent was obtained before completing the online survey. Up to 200 respondents (parents) and 100 young people were intended to be recruited to ensure sufficient numbers of participants to map the range of issues and experiences [13], identify common issues across them, carry out meaningful subgroup analyses and provide rich data from the open text qualitative responses [14, 15].

Survey

The core set of questions was based on currently available literature [16,17,18], expert clinician input, co-produced with CYA and parents of a child with cancer (n = 7) and then adapted by parents and CYA with a kidney condition (n = 13). Further refinement was performed over two video-conference focus groups with a small number of CYA charity group representatives (n = 3) who clarified any contentious questions with their groups to come up with the final survey. We sought opinion on content, phrasing, usability and value of each question for research. The survey consisted of two sections consisting of (a) qualitative open questions and (b) quantitative closed statements.

Seven open questions were asked: Experiences: Can you tell us about your experiences and views on the virus in relation to your child with a kidney condition?; Hospital: I worry the hospital is no longer a safe place during the virus outbreak—if so in what way?; Positive aspects: I have experienced some positive things to come out of the virus outbreak, either at home or related to care, if so in what way?; Mood: In relation to the virus outbreak, my mood or behaviour has changed, if so in what way?; Information: Can you tell us where you get information on the virus and what other information you might need?; Decisions: Can you tell us how you make decisions about looking after your child in relation to the virus?; and Support: What additional support would you like, at home or in hospital, in relation to the virus?. These open questions were intended to be completed prior to the closed statements which guided the respondent’s thinking. A final free text question asked respondents whether they had any further comments.

The closed statement items were in the following domains: Experiences (n = 13), Information (n = 7), Decisions (n = 10) and Support needs (n = 5). A small number of items differed between the parent and CYA surveys. Response options were Not at all, A little, Quite a bit and Very much (except for two conditional questions with Yes/No as response options). For simplicity, COVID-19 was referred to as ‘the virus’. Demographic information was also collected, such as age and treatment.

Data analysis

The qualitative open questions data were subjected to a thematic content analysis, informed by a three-stage coding process [19, 20]: Stage 1: Initial samples were open-coded into broad comment categories by two researchers (SC, AR), refining an existing framework, and resolving any conflicts with a third researcher (ASD); Stage 2: The framework was used to categorise all comments from the data, with further refinement; and Stage 3: Overarching themes were identified from analysis of similarities in the content between categories. Number of comments were counted, to identify weight of themes. Because of the overlap in comments to categories, the total number of comments does not match the number of participants. Illustrative quotes that most represented each subtheme were chosen by consensus (SC, AR, ASD).

Descriptive statistics were carried out using IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) to summarise the demographic data for the two participant groups, and undertake simple descriptive statistics of the closed statement items (collapsing the lowest two response options (Not at all, A little) and the highest two response options (Quite a bit, Very much) into a binary outcome). Subgroup analyses were carried out on an item level, using chi-squared analyses at the two-sided significance level p < 0.05, according to whether young people were in the shielded group (instruction from UK Government to stay isolated) or not, separately for the CYA and parent samples. No subgroup analyses were carried out according to age.

Results

Participants

One-hundred and eighteen CYA with kidney conditions answered the survey, median age was 21 years (range 12–30 years) with 40 (33.9%) under 18 years old. Respondents’ ethnicities were similar to age-matched prevalent Renal Registry patient cohort with 96 (81.4%) identifying as white.

One-hundred and ninety-seven parents completed the survey, the majority mothers (n = 169, 85.8%) and of white ethnicity (n = 186, 94.4%). The median age of the children of responding parents was 10 years (range 0–18 years). Table 1 summarises respondents’ characteristics.

Quantitative results from survey responses

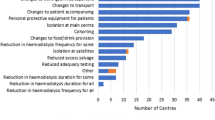

The study generated quantitative results from the closed statement items, which are presented as those who responded with ‘Quite a bit’ or ‘Very much’ for both CYA (Fig. 1) and parents (Fig. 2). Subgroup analyses, comparing those who were shielded with those who were not, are also included.

The majority of CYA were vigilant about virus symptoms (68%) or ‘kidney’ symptoms (77%), whilst 40% worried about the virus. For 70% of CYA, education and work had been impacted. Information came from their clinical team (45%) or through accessing social media (75%). Sixty-one percent of CYA reported being seen less by their clinical team compared to before the pandemic.

Most parents worried about the virus (72%), or were vigilant about virus symptoms (83%) or kidney symptoms (87%). Over half of the parents (57%) felt protected with the shielding advice. Information came from clinical teams (43%) but more from social media (67%). A third of those who accessed information through social media were left feeling anxious (31%). Parents worried that their child would catch the virus from them (65%) and worried about the impact on other children at home (66%). Only a small minority reported that they would like more support from an educational institution (CYA 14%, parents 20%) or support to reduce worries (CYA 21%, parents 31%).

Shielded vs. non-shielded patients

Results of subgroup analyses that assessed differences between the shielded and non-shielded groups are summarised in Figs. 1 and 2. Over half of CYA, either responding themselves (62%) or included by parental response (57%), were in the shielded group—they recalled receiving a letter or text message from the government. A small number of respondents (10%) were unaware if they were shielded or not. There was no perceived difference between the groups in whether they saw their clinical teams less during the lockdown period (shielded 43% vs. non-shielded 35%, p = 0.47).

For CYA, significant differences between shielded and non-shielded groups were found in 8 out of 29 (28%) questions in all domains except support needs. Shielded CYA reported being more vigilant about virus symptoms (76% vs. 50%, p = 0.05) and kidney symptoms (87% vs. 55%, p = 0.009), more worried about feeling isolated (55% vs. 25%, p = 0.035), more likely that isolation brought up negative memories (73% vs. 27%, p = 0.01) and felt more protected with shielding advice (66% vs. 25%, p = 0.003). Shielded CYA felt that they received adequate information from their clinical teams (62% vs. 5%, p < 0.001), should be isolated (64% vs. 33%, p = 0.03) and stated that it was more difficult to adhere to their treatment plans (22% vs. 0%, p = 0.03).

For parents, shielded vs. non-shielded group differences were found in 16 out of 32 (50%) questions throughout all domains. To highlight the 7 most significant differences (p < 0.01), parents of shielded children were significantly more vigilant about virus symptoms (90% vs. 71%, p = 0.004) and worried about their child going outside (67% vs. 44%, p = 0.006). They reported better information from their clinical teams (53% vs. 25%, p = 0.001). In the decisions domain more parents thought their child should be isolated to their immediate families (64% vs. 35%, p = 0.001) or just their parents/caregivers (41% vs. 18%, p = 0.007); they worried more about home visits from nurses/caregivers (p = 31% vs. 10%, p = 0.006) and worried more about the impact on other children in the family (77% vs. 47%, p = 0.002).

Qualitative findings from open text questions

Qualitative open questions contained a total of 1,406 quotes (228 Experiences, 158 Hospital, 165 Positive aspects, 262 Mood, 171 Information, 214 Decision making and 208 Support). There was considerable overlap in answers given, and it was observed that participants, after answering the first question about their Experiences, were repeating their responses in the remaining open questions.

Thematic content analyses with example quotes from the Experiences question are presented in Table 2. Five main themes emerged concerning the virus (risk of infection, information guidance and advice and change in healthcare provision) or about lockdown and isolation (the psychological and social impact and keeping safe).

The strongest signal from both CYA (n = 21) and parents (n = 65) related to the concern that contracting the virus would lead to serious illness and they were taking extra precautions to shield. However, this was not universal; a sizable number of comments from CYA (n = 12) and parents (n = 17) stated they had no concerns about the virus or had initial concerns which subsided. The predominant comments from CYA (n = 11) and parents (n = 14) in the information, guidance and advice subtheme, felt they had received only limited information or mixed messages.

When sub-themed by psychological and social impact, CYA (n = 37) generated many more comments compared to parents (n = 8). The most common comments from CYA was they felt they were missing out on work-related and educational opportunities (n = 14), missing family and friends (n = 9) and compared to their peers they lived with more restrictions and were missing out on life (n = 8).

In the keeping safe under lockdown subtheme, CYA (n = 7) and parents (n = 6) were worried about adjusting to life after the lockdown. Several CYA (n = 7) were also concerned about the general public not following social distancing and hygiene rules, thus putting everyone at risk.

Findings from the other six open questions are summarised in Table 3.

Discussion

This is the first study specifically surveying CYA with kidney conditions and their parents’ experience of the COVID-19 pandemic during lockdown. Both CYA and parents were vigilant about the virus and kidney symptoms. Some notable differences exist between the two groups, e.g. CYA worried less about the virus than parents. CYA felt the impact of lockdown most keenly in terms of education and work; parents were particularly worried about their child catching the virus from them and the impact on others at home. Significant differences were found between shielded and non-shielded groups. Information about the virus was gained from multiple sources including social media but they were not always trusted. Free text responses indicated a strong desire for more tailored information to make sensible decisions about their individual risk. We determined that there was a strong sense of pragmatism as there was little demand for extra support and decisions were largely based on common sense.

Unique challenges of young people with chronic kidney diseases during COVID

COVID-19 affected our patient population very differently according to age. Less than five kidney replacement patients out of a cohort of more than 1,000 children in the UK had a positive COVID-19 test up until mid-July 2020, at completion of our study, and none had serious disease [21]. Similar mild outcome was found in a global study of COVID-19 in children on immunosuppression for kidney diseases [22]. Reassuring data is also available for young adults although these subgroups are not usually made explicit [10]. Our study indicates that the majority of CYA and parents base their decisions on ‘common sense and what they could reasonably do to protect themselves or their child’ and would therefore value further tailored information based on outcome data to make decisions for themselves and their family.

CYA (42%) did report being worried about coming out of lockdown (this question was not specifically asked of parents). This alongside already reported psycho-social vulnerabilities in this group indicate a likely need for increased mental health and well-being support [7]. This will be particularly important during the on-going pandemic as CYA and parents adjust to the changing COVID-19 landscape, particularly regarding their risk status and return to school, further education or the workplace. Recommendations from professional groups can also help inform and reassure CYA and parents as they potentially move from being reclassified as ‘extremely clinically vulnerable’ to being in a ‘not at increased risk group’ [12]. The positive impact of lockdown on health and well-being should also be evaluated and be reflected in healthcare messages and provisions post-lockdown.

In many countries, specific measures are advised for those thought to be at highest risk; in the UK an estimated 2 million clinically extremely vulnerable people were identified and asked to shield. This is the first study with comparable shielded and non-shielded CYA. Differences in several key domains were found, especially in the parent responses, suggesting the amplification of negative experiences within the shielded group. Both CYA and parents in the shielded group worried about feeling isolated. CYA who were shielded reported feeling restricted, not being able to see friends and family, which also led to mood changes such as anxiety and ‘feeling depressed’. Similar findings were found in a cohort of Chinese children on kidney replacement therapy during lockdown—11% of families reported anxiety and 13% depression [23].

Paradoxically, whilst experiencing negative feelings around isolation, CYA and parents recognised its role in keeping them safe and valued being shielded. This was evident in the findings from the free text responses where CYA reported not being too worried at first, but increasingly feeling concerned about other people not following social distancing rules.

Strengths and limitation of study

This study has several strengths. It is a national study, co-produced with parents and CYA, representing their voices across a wide range of kidney issues during the pandemic. It is the first study that has directly asked children and young adults living with a kidney condition about the effects of COVID-19 and lockdown. Qualitative research can provide valuable insights into patient and parent experiences and inform health care workers about where to target resources. CYA respondents but not parent respondents were ethnically representative of the UK Renal Registry (UKRR) population [24].

Limitations of the study include the contracted time period in which it was necessarily undertaken and the inability to triangulate data between CYA and their respective parent for those < 19 years or explore themes in depth with targeted interviews or user groups. The self-reporting nature of the survey precluded verification of medical background, treatment, shielding category or adherence to public health recommendations. We did not mandate answers to any of the qualitative or quantitative questions, including shielding categories, resulting in missing data increasingly more prevalent later in the survey. The patients were a heterogeneous group covering the whole spectrum of disease severity. We did not measure access to virtual clinics or urban/rural geography which may have influenced respondents’ experience of healthcare. The use of social media to distribute and access the study may have also limited access to English-speaking individuals with compatible devices/smartphones [25].

Application of this study

This study offers clinicians managing chronic disease information about how CYA and parents perceive risk and how they access information and support during a pandemic. The study indicated that CYA and parents want clear tailored information about individual risk from those that they trust, their clinical team, and accessing trusted information via social media is preferred. In a recent analysis only two thirds of cancer-related social media information was accurate, so debunking COVID-19 misinformation is a challenge for healthcare teams and governments [26, 27]. Improved information and guidance will also be needed to reassure CYA and parents that they can now access healthcare safely. Our suggestion to help address gaps in information and support needs based on study responses is listed in Table 4.

The challenge now will be to keep pace with the fluctuations in virus prevalence and risk, ensure the safe delivery of ongoing care including transplantation and provide support alongside tailored advice to CYA and parents so they can continue to live well during a pandemic.

References

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395:912–920

Zhou S-J, Zhang L-G, Wang L-L, Guo Z-C, Wang J-Q, Chen J-C, Liu M, Chen X, Chen J-X (2020) Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29:749–758

Bakr A, Amr M, Sarhan A, Hammad A, Ragab M, El-Refaey A, El-Mougy A (2007) Psychiatric disorders in children with chronic renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol 22:128–131

Fukunishi I, Honda M (1995) School adjustment of children with end-stage renal disease. Pediatr Nephrol 9:553–557

Kilicoglu AG, Bahali K, Canpolat N, Bilgic A, Mutlu C, Yalçın Ö, Pehlivan G, Sever L (2016) Impact of end-stage renal disease on psychological status and quality of life. Pediatr Int 58:1316–1321

Amr M, Bakr A, El Gilany AH, Hammad A, El-Refaey A, El-Mougy A (2009) Multi-method assessment of behavior adjustment in children with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 24:341–347

Hamilton AJ, Caskey FJ, Casula A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Inward CD (2019) Psychosocial health and lifestyle behaviors in young adults receiving renal replacement therapy compared to the general population: findings from the SPEAK study. Am J Kidney Dis 73:194–205

Public Health England (2020) Guidance on shielding and protecting people who are clinically extremely vulnerable from COVID-19 (First published 21 March 2020). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-on-shielding-and-protecting-extremely-vulnerable-persons-from-covid-19. Accessed 19 February 2021

Tse Y, Plumb L, Hulton S, Inward C (2020) Information and guidance for children on haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and immune suppression including renal transplants (Updated 20 August 2020). British Association for Paediatric Nephrology. https://renal.org/health-professionals/covid-19/bapn-resources. Accessed 19 February 2021

Ravanan R, Callaghan CJ, Mumford L, Ushiro-Lumb I, Thorburn D, Casey J, Friend P, Parameshwar J, Currie I, Burnapp L, Baker R, Dudley J, Oniscu GC, Berman M, Asher J, Harvey D, Manara A, Manas D, Gardiner D, Forsythe JLR (2020) SARS-CoV-2 infection and early mortality of waitlisted and solid organ transplant recipients in England: a national cohort study. Am J Transplant 20:3008–3018

Chen K, Didsbury M, van Zwieten A, Howell M, Kim S, Tong A, Howard K, Nassar N, Barton B, Lah S, Lorenzo J, Strippoli G, Palmer S, Teixeira-Pinto A, Mackie F, McTaggart S, Walker A, Kara T, Craig JC, Wong G (2018) Neurocognitive and educational outcomes in children and adolescents with CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13:387–397

Green P (2020) Risks to children and young people during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ 369:m1669

Hill R (1998) What sample size is “enough” in internet survey research. Interpersonal Comput Technol 6:1–12

Gay LR, Diehl PL (1992) Research methods for business and management. Macmillan, New York

Safdar N, Abbo LM, Knobloch MJ, Seo SK (2016) Research methods in healthcare epidemiology: survey and qualitative research. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 37:1272–1277

Morgan JE, Cleminson J, Stewart LA, Phillips RS, Atkin K (2018) Meta-ethnography of experiences of early discharge, with a focus on paediatric febrile neutropenia. Support Care Cancer 26:1039–1050

Morgan JE, Phillips B, Stewart LA, Atkin K (2018) Quest for certainty regarding early discharge in paediatric low-risk febrile neutropenia: a multicentre qualitative focus group discussion study involving patients, parents and healthcare professionals in the UK. BMJ Open 8:e020324. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020324

Robertson EG, Wakefield CE, Shaw J, Darlington AS, McGill BC, Cohn RJ, Fardell JE (2019) Decision-making in childhood cancer: parents’ and adolescents’ views and perceptions. Support Care Cancer 27:4331–4340

Mason J (2017) Qualitative researching. Sage, London

Wagland R, Bracher M, Drosdowsky A, Richardson A, Symons J, Mileshkin L, Schofield P (2017) Differences in experiences of care between patients diagnosed with metastatic cancer of known and unknown primaries: mixed-method findings from the 2013 cancer patient experience survey in England. BMJ Open 7:e017881. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017881

Plumb L, Benoy-Deeney F, Casula A, Braddon FE, Tse Y, Inward C, Marks S, Steenkamp R, Medcalf J, Nitsch D (2020) COVID-19 in children with chronic kidney disease: findings from the UK renal registry. Arch Dis Child 106:e16

Marlais M, Wlodkowski T, Vivarelli M, Pape L, Tönshoff B, Schaefer F, Tullus K (2020) The severity of COVID-19 in children on immunosuppressive medication. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 4:e17–e18

Zhao R, Zhou Q, Wang X-W, Liu C-H, Wang M, Yang Q, Zhai Y-H, Zhu D-Q, Chen J, Fang X-Y (2020) COVID-19 outbreak and management approach for families with children on long-term kidney replacement therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15:1259–1266

Plumb L, Casula A, Magadi W, Braddon F, Lewis M, Marks SD, Shenoy M, Sinha MD, Maxwell H (2018) UK Renal Registry 20th Annual Report: Chapter 11 Clinical, Haematological and Biochemical Parameters in Patients on Renal Replacement Therapy in Paediatric Centres in the UK in 2016: National and Centre-specific Analyses. Nephron 139:273–286

Phares V, Lopez E, Fields S, Kamboukos D, Duhig AM (2005) Are fathers involved in pediatric psychology research and treatment? J Pediatr Psychol 30:631–643

Gage-Bouchard EA, LaValley S, Warunek M, Beaupin LK, Mollica M (2018) Is cancer information exchanged on social media scientifically accurate? J Cancer Educ 33:1328–1332

Limaye RJ, Sauer M, Ali J, Bernstein J, Wahl B, Barnhill A, Labrique A (2020) Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digit Health 2:e277–e278

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all children, young adults and parents who contributed their time and experiences to this study especially Southampton Children’s Hospital patients and families (Thomas Allfree, Alisia Coles, Jack Howe, Amy Kinrade, Madison Parffett, Alisa Braha, Leon Bicknell, Sian Roberts, Sarah Allfree, Angela Kinrade, Lisa Coles, Emma Roberts, Christopher Bicknell) and the Young Adult Kidney Group (Madeleine Warren, Sarah Green, Holly Loughton). We would also like to thank Kidney Care UK (Paul Bristow, Suzan Yianni), Kidney Research UK (Sandra Currie, Aisling McMahon) and the young adult and youth workers who supported the dissemination of the study. Special thanks to colleagues in the Renal Association and British Association for Paediatric Nephrology (including patient representative Kamal Dhesi) and in our units for championing the study, and apologies for any omissions: Alder Hey Children’s Hospital Liverpool (Louise Oni, Caroline Jones), Birmingham Children’s Hospital (Larissa Kerecuk), Bristol Royal Hospital for Children (Janet Dudley, Lucy Plumb), Evelina London Children’s Hospital (Grainne Walsh, Christopher Reid), Great Ormond Street Hospital London (Kjell Tullus, Daljit Hothi), Leeds Children’s Hospital (Amanda Newnham), Newcastle Hospital (Lauren Mawn, Helen Ritson), Nottingham Children’s Hospital (Andrew Lunn), Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children (Mairead Convery), Royal Hospital for Children Glasgow (Ben Reynolds), Southampton Children’s Hospital (Caroline Anderson, Rosemary Dempsey, Sarah Shameti, Eleanor Stubbs), University Hospitals Southampton NHS Foundation Trust and Queen Alexandra Hospital Portsmouth (Kirsten Armstrong) and University Hospital of Wales (Shivaram Hegde).

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

We thank Kidney Care UK and Kidney Research UK for funding and publicising the survey. Funders had no part in data collection, interpretation or reporting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in conception and design, drafted the article and approved the final manuscript. SC, ARS, ASD and DC obtained ethics, designed the data collection platform, collected data and performed thematic analysis and statistics. YT, KT, DW, TP and AN organised the kidney community as stakeholders and to promote the study. AN obtained funding. ASD leads the family of SHARE studies.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(PPTX 43 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tse, Y., Darlington, AS.E., Tyerman, K. et al. COVID-19: experiences of lockdown and support needs in children and young adults with kidney conditions. Pediatr Nephrol 36, 2797–2810 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-021-05041-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-021-05041-8