Abstract

Background

A correlation between renal mass and nephron number in newborns allows the use of total kidney volume at birth as a surrogate for congenital nephron number. As the bone morphogenetic protein type 4 (BMP4), and its receptor type 1A (BMPR1A, ALK3), play an important role in renal development, we hypothesized that common, functional polymorphisms in their genes might be responsible for variation in kidney size among healthy individuals.

Methods

We recruited 179 healthy full-term newborns born to healthy women. Kidney volume was measured sonographically. Total kidney volume (TKV) was calculated as the sum of left and right kidneys, and normalized for body surface area (TKV/BSA). Genomic DNA was extracted from umbilical cord blood leukocytes, and c.455T > C (rs17563) BMP4 and c.67 + 5659A > T (rs7922846) BMPR1A genotypes were identified by PCR-RFLP.

Results

TKV/BSA in newborns carrying at least one A BMPR1A allele (AA + AT) was significantly reduced by approximately 13 % as compared with TT homozygous newborns (106.7 ± 21.5 ml/m2 vs. 122.7 ± 43.8 ml/m2, p < 0.02). No significant differences in TKV/BSA were found among newborns with different BMP4 genotypes.

Conclusions

Results suggest that rs7922846 BMPR1A polymorphism may account for subtle variation in kidney size at birth, reflecting congenital nephron endowment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suboptimal nephron number may be associated with increased risk for essential hypertension and susceptibility to renal injury [1–4], but the factors that set nephron number during kidney development remain largely undefined [5]. Nonetheless, genetic studies in humans and mice have provided valuable insights into the possible genetic contribution and molecular mechanisms leading to normal nephron endowment and renal hypoplasia [2]. In humans, final nephron endowment for life is determined during late gestation and displays wide individual variation (210,332 to 2,702,079 nephrons per kidney) [6–8]. El Kares et al. hypothesized that congenital nephron number is a multifactorial trait controlled by the interaction of environmental factors and genetic variants that influence the extent of branching nephrogenesis during fetal life [9]. In addition, confirmation of a strong correlation between renal mass and nephron number in newborns allows the use of the total kidney volume at birth (measured by ultrasonography) as a surrogate for congenital nephron number [10].

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) belong to the Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) family, with more than 30 members that bind to two types of serine-threonine kinase receptors, i.e., type 1 (BMPR1) and type 2 (BMPR2) receptors [11]. Although BMPs were first identified as factors that induce the formation of bone and cartilage when implanted at ectopic sites in rats [11], they are now known to be implicated in a variety of developmental processes [12]. The spatial and temporal expression of Bone Morphogenetic Protein type 2 or type 4 (BMP2 or BMP4, respectively) and their shared receptor, BMP receptor type 1A (BMPR1A)—also known as Activin-Like Kinase 3 (ALK3) [11]—suggests a functional role for BMP signaling during the formation of intermediate mesoderm-derived organs, including the mammalian kidney [13]. In 2008, Weber et al. identified BMP4 mutations causing renal hypodysplasia, characterized by a reduction in nephron number and a small overall kidney size [14]. Recently, Di Giovanni et al. reported that Alk3-deficient mice exhibit simple renal hypoplasia characterized by decreases in both kidney size and nephron number, but with normal tissue architecture [13]. In 2009, Capasso et al. [15] found that cutaneous melanoma-associated c.455T > C (rs17563) BMP4 polymorphism, resulting in an amino acid change from valine to alanine at residue 152 (p.Val152Ala), affects BMP4 gene expression, and Boettcher et al. suggested that the obesity-associated c.67 + 5659A > T (rs7922846) BMPR1A polymorphism modulates BMPR1A mRNA levels [16].

Thus far, several common polymorphisms in developmental genes including PAX2 [5], RET [10], ALDH1A2 [9], OSR1 [17], and ACE [18] have been associated with subtle variation in kidney size at birth. These findings lend support to the hypothesis that common, functional polymorphisms in BMP4 and/or BMPR1A may be responsible for the variation in nephron number that is seen amongst healthy individuals. To verify this hypothesis, we examined the association of nonsynonymous rs17563 BMP4 and intronic rs7922846 BMPR1A polymorphisms with congenital kidney volume, a surrogate measure of the number of nephrons, in a cohort of healthy, full-term newborns in Poland.

Methods

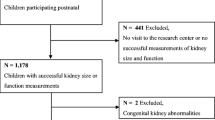

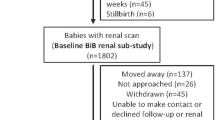

Study subjects

At the Department of Neonatal Diseases at the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, we prospectively recruited 179 consecutive healthy Polish newborns (79 females and 100 males), born after the end of the 37th week of gestation to healthy women with uncomplicated pregnancies. All children were breast-fed and free of medication. Twins, infants of mothers with preeclampsia, hypertension of any cause, diabetes, history of illicit substance use, or antenatal steroid therapy were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were congenital infection, intra-uterine growth restriction (i.e., below the 10th percentile birth mass, length, or head circumference), chromosomal aberrations or congenital malformations. At birth, cord blood of newborns was obtained for isolation of genomic DNA. The gender of the newborn, birth mass (BM), and birth length (BL) were taken from standard hospital records. Body surface area (BSA) was calculated as the square root of [BL (cm) × BM (kg)/3600] according to Mosteller [19]. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and parents gave informed consent.

Kidney volume measurement

Sonographic examination was performed in newborns on the third day after delivery with an EnVisor C machine (Philips Canada, Markham, Ontario, Canada) using a 5-MHz sector probe (Philips Canada) and 10-MHz linear probe (Philips Canada) as described previously [20, 21]. Left and right kidney volumes (LKV and RKV, respectively) were calculated using the following formula for volume of an ellipsoid: \( \left[ {{\text{kidney}}\,{\text{volume}} = \left( {{{4} \left/ {3} \right.}} \right) \times {\text{Pi}} \times \left( {{{\text{length}} \left/ {{2}} \right.}} \right) \times \left( {{{\text{height}} \left/ {{2}} \right.}} \right) \times \left( {{{\text{width}} \left/ {2} \right.}} \right)} \right] \) [5]. Total kidney volume (TKV) was calculated as the sum of LKV and RKV. Subsequently, TKV was normalized for body surface area (TKV/BSA) [5, 20].

Determination of BMP4 and BMPR1A genotypes

Genomic DNA from cord blood was isolated with the QIAamp Blood DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany). For the analysis of the rs17563 BMP4 gene polymorphism, a polymerase chain reaction/restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR/RFLP) method was designed with the following primer pair: forward: 5′-ACTCTgCTTTTCgTTTCCTCTTTA-3′ and reverse 5′-ggCCCAATTCCCACTCC-3′ primers (TIB MOL BIOL, Poznań, Poland). The BMP4 amplicons were subsequently digested with HphI enzyme (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania). The PCR BMP4 product of 395 base pairs (bp) was cut into fragments of 244, 75, 62, and 14 bp from the T allele and 306, 75, and 14 bp from the C allele.

DNA fragments that contained the rs7922846 BMPR1A polymorphism were amplified by PCR with forward 5′-TTTCAgCGCTCAATAgACAC-3′ and reverse 5′-TCCCTCCCCCTTTCATA-3′ primers. PCR-RFLP with the AccI restriction enzyme was performed. In the case of the T allele, the final product of 541 bp remained undigested, while the A variant gave restriction fragments of 352 bp and 189 bp. The restriction fragments in each case were electrophoretically separated and visualized in ethidium bromide-stained 3 % agarose gels.

Statistical analysis

Possible divergence of BMP4 or BMPR1A genotype frequencies from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was assessed using a χ2 test. The distribution of each quantitative variable was tested for skewedness. Quantitative data were presented as means ± SD. Association of either gender or genotype (with respect to dominant and recessive modes of inheritance of the minor alleles) with each outcome variable was assessed by Student’s t test using STATISTICA (StatSoft, Inc. (2011), version 10). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

All PCR samples were genotyped twice and a concordance rate of 100 % was attained. There were 57 CC BMP4 homozygotes (31.8 %), 93 CT heterozygotes (52.0 %), and 29 TT homozygotes (16.2 %). There were 82 AA BMPR1A homozygotes (45.8 %), 81 AT heterozygotes (45.3 %), and 16 TT homozygotes (8.9 %). The frequencies of the minor alleles were: 42.2 % (39.5 % in newborn males and 45.6 % in newborn females) and 31.6 % (33.0 % in newborn males and 29.7 % in newborn females) for T BMP4 and T BMPR1A, respectively.

Both BMP4 and BMPR1A genotype distributions conformed to the expected Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p = 0.545 and p = 0.607, respectively). Characteristics of the newborn cohort (n = 179) with respect to gender are shown in Table 1.

The distribution of these characteristics in our cohort, including kidney size, approached normality (skewedness < 2 for all variables). The mean values of birth mass and BSA in male newborns were significantly higher as compared with female newborns. No significant differences in gestational age, birth length, LKV, RKV, LKV/RKV, TKV, and TKV/BSA were found between male and female newborns.

Characteristics of kidney volumes with respect to rs17563 BMP4 and rs7922846 BMPR1A polymorphisms are shown in Table 2. Mean values of TKV and TKV/BSA in newborns with at least one A allele (AA + AT) were significantly lower as compared with TT BMPR1A homozygotes (24.7 ± 5.5 ml versus 28.0 ± 10.0 ml and 106.7 ± 21.5 ml/m2 versus 122.7 ± 43.8 ml/m2, respectively). No significant differences in LKV, RKV, LKV/RKV ratio were found among newborns with different BMPR1A genotypes. No significant differences in LKV, RKV, LKV/RKV ratio, TKV, and TKV/BSA were found among newborns with different BMP4 genotypes.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates for the first time an association of rs7922846 (c.67 + 5659A > T) BMPR1A polymorphism, but not rs17563 (c.455 T > C) BMP4, with kidney size in Polish full-term newborns. Total kidney volume, standardized for body surface area (TKV/BSA), in newborns carrying at least one A BMPR1A allele (AA + AT) was reduced by approximately 13 % as compared with TT homozygous newborns (a recessive genetic model for the T allele). The number of nephrons formed during fetal organogenesis seems to be an important determinant of human health, and reduced nephron endowment may result in pathological states ranging from early renal failure to adult-onset hypertension, depending on the severity of nephron deficiency [1–4].

We found no relationship between rs7922846 and kidney volume under the assumption of dominant genetic model for the T allele (TT + AT versus AA). Therefore, our results support a dominance of the A BMPR1A allele, which is evidenced in the similarity of kidney volumes, TKV/BSA in particular, in carriers of at least one A allele. Recently, Böttcher et al. [16] reported a significant association between rs7922846 variant and mRNA expression of BMPR1A only in the dominant model for the T allele (TT + AT versus AA). The recessive model, however, was not calculated due to the small sample size of the groups of subjects homozygous for the T allele [16]. Further research may be needed to determine which genetic model best matches the actual underlying mode of inheritance of the A allele, associated with reduced total kidney volume.

Although the TKV/BSA was significantly associated with BMPR1A variant, the effect of this polymorphism was less evident when individual kidneys were evaluated. We previously showed that the common angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) insertion/deletion (I/D) polymorphism was not only associated with the TKV/BSA but also with individual kidney volumes [18]. While the ACE DD homozygotes accounted for around 25 % of all genotypes in the aforementioned study [18], the frequency of BMPR1A TT homozygotes in the present study was 8.9 %. Therefore, the low statistical power due to insufficient sample size may have led to borderline significance for individual, left and right kidneys.

The intermediate mesoderm, differentiating into the metanephric blastema (and then metanephric mesenchyme) and ureteric bud [22], gives rise to the permanent kidney, but extrinsic signals altering gene expression are required to commit the intermediate mesoderm to a renal lineage [13]. James and Schultheiss showed that BMP-ALK signaling modulates gene expression patterns in the intermediate mesoderm in vitro and in vivo [23]. BMPR1A (ALK3) is one of the three type 1 BMP (bone morphogenetic protein) receptors that are essential for BMP signaling [24]. Böttcher et al. [16] showed that non-diabetic homozygous carriers of the obesity risk alleles for rs7922846 (c.67 + 5659A) and three other BMPR1A variants (rs7095025, rs11202222, and rs10788528) had higher visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue mRNA expression of BMPR1A, yet only rs7922846 was significantly associated with increased visceral mRNA expression [16]. Moreover, this polymorphism is in strong linkage disequilibrium with another nonsynonymous rs11528010 BMPR1A polymorphism causing the amino acid substitution of proline by threonine at residue 2 (p.Pro2Thr) located in the potential BMPR1A signal peptide chain that could affect posttranslational transport of BMPR1A [16].

In our study, carriers of the A allele of BMPR1A polymorphism, associated with increased ALK3 mRNA expression, had significantly smaller kidney size as compared with TT homozygous newborns. Animal studies show that both decreased and increased expression of active ALK3 receptor may ultimately result in deficient UB branching [25, 26]. Although both ALK3 loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutation mouse models exhibit similar outcomes, the mechanisms underlying these outcomes are distinct [26]. While ALK3 deficiency disrupts UB patterning—an increased number of first and second UB branches followed by a decrease in the number of subsequent branches formed—resulting in an overall reduction in UB number, the constitutive overexpression of ALK3 inhibits branching morphogenesis [26]. As even minor defects of UB branching can result in a marked decrease in nephron number [27], we thus hypothesize that the reduced kidney size seen in healthy newborns carrying at least one A BMPR1A allele might be due to subtle decreases in the efficiency of UB branching, possibly mediated by increased expression of BMPR1A mRNA [16]. However, whether expression of BMPR1A gene mRNA level correlates with protein abundance remains to be determined.

Bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) has been implicated in several aspects of embryonic development, especially in those organs in which epithelial–mesenchymal interactions are essential for development, such as the kidney [28, 29]. Additionally, it is a known regulator of UB branching; firstly, by inhibiting ectopic budding from the nephric (Wolffian) duct and, secondly, by promoting elongation of the branching ureter [30]. Previously, BMP signaling has been shown to regulate nephron number in mice, as deletion of the Cv2 molecule, which normally has pro-BMP function, resulted in reduced nephron endowment [31]. Although three missense mutations in BMP4 have been recently detected in children with renal hypodysplasia (RHD), characterized by reduced kidney size and/or maldevelopment of the renal tissue [14], we failed to detect an association between rs17563 BMP4 polymorphism and newborn kidney size. There was, however, a trend towards lower individual and total kidney volumes in carriers of the CC genotype. Recently, Cappaso et al. [15] reported significantly lower BMP4 mRNA levels in CC homozygotes as compared to carriers of the T allele. Thus, the study cohort might be too small to definitively exclude effects of this BMP4 variant. However, if the lack of association is a true negative result, this finding seems to be supported by Cain and Bertram [29], who showed that despite reduced endogenous BMP4 mRNA levels, most BMP4 heterozygous mouse embryos were still able to facilitate normal ureteric branching morphogenesis during development. Although many mutations within BMP4 leading to various phenotypes are known [32], to our knowledge, rs17563 is the only identified polymorphism in the coding region [33]. As the rs17563 BMP4 polymorphism was previously found to be significantly associated with BMP4 mRNA levels and BMP4 plasma levels [15], we also tried to account for possible ligand-dependent (BMP4) up- or down-regulation of BMPR1A. To do this, we analyzed TKV values for compound genotypes composed of BMP4 and BMPR1A, but no associations were found (data not shown).

In order to minimize the effects of potential confounding variables that could create a spurious association, the study was conducted in a carefully selected group of newborns all of whom met all criteria for inclusion. The sonographic examinations of kidney size were performed according to protocols in the literature that give reproducible results, and kidney volumes were similar to those of a large cohort of Danish newborns who were studied within the first 5 days of life [20]. The BMPR1A genotype distribution in our group was in accordance with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. TKV/BSA in infants with at least one A BMPR1A allele ranged from 54.5 to 173.2 ml/m2 versus 69.2 to 219.3 ml/m2 in TT homozygotes, and the left/right kidney volume ratio did not differ among newborns with the various BMPR1A genotypes. Therefore, it is wrong to assume that the significant association is due to a few newborns with very small kidneys or with unilateral renal hypoplasia.

The potential weakness of the present study stems from the fact that our sample was not systematically tested for genetic heterogeneity. Population stratification is a concern in both case-control and cross-sectional studies [34]. Moreover, Berger et al. showed that population substructures can be detected even in an apparently homogenous population [35]. The confounded association resulting from stratification or admixture within a population can be reduced by matching by geographical region and/or by markers of ethnic origin [36]. The population now inhabiting the region of West Pomerania resulted from extensive mixing of Polish people from all regions of Poland after the Second World War and therefore can provide a representative sample of a Caucasian-European population [37]. In addition, the rs7922846 allele frequencies were similar to those reported in adult control subjects in a Leipzig cohort, a self-contained Sorbian population in Germany [16], and Utah residents with ancestry from Northern and Western Europe from the HapMap project [38]. Although, we believe, it is very unlikely that our cohort of newborn infants is a biased sample due to population stratification, other studies in populations of the highest possible level of homogeneity may be needed.

In summary, our data suggest that common genetic variation in BMPR1A may play a role in early human nephrogenesis, through putative increase in BMPR1A mRNA expression and thereby, presumably, defective ureteric bud branching leading to subtle reduction in nephron number and subsequently to slightly smaller kidney size in healthy newborns. Furthermore, rs7922846 BMPR1A polymorphism may, in concert with other common polymorphisms in developmental genes including PAX2 [5], RET [10], ALDH1A2 [9], OSR1 [17] or ACE [18], partially account for subtle variation in kidney size at birth reflecting congenital nephron endowment. Thus, newborns possessing an unfavorable polygenic profile associated with reduced nephron number may benefit from heightened surveillance for essential hypertension in adulthood.

References

Schedl A (2007) Renal abnormalities and their developmental origin. Nat Rev Genet 8:791–802

Cain JE, Di Giovanni V, Smeeton J, Rosenblum ND (2010) Genetics of renal hypoplasia: insights into the mechanisms controlling nephron endowment. Pediatr Res 68:91–98

Brenner BM, Garcia DL, Anderson S (1988) Glomeruli and blood pressure. Less of one, more the other? Am J Hypertens 1:335–347

Keller G, Zimmer G, Mall G, Ritz E, Amann K (2003) Nephron number in patients with primary hypertension. N Engl J Med 348:101–108

Quinlan J, Lemire M, Hudson T, Qu H, Benjamin A, Roy A, Pascuet E, Goodyer M, Raju C, Zhang Z, Houghton F, Goodyer P (2007) A common variant of the PAX2 gene is associated with reduced newborn kidney size. J Am Soc Nephrol 18:1915–1921

Douglas-Denton RN, McNamara BJ, Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Bertram JF (2006) Does nephron number matter in the development of kidney disease? Ethn Dis 16:S2-40–S2-45

Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Singh GR, Douglas-Denton R, Bertram JF (2006) Reduced nephron number and glomerulomegaly in Australian Aborigines: a group at high risk for renal disease and hypertension. Kidney Int 70:104–110

Puelles VG, Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Diouf B, Douglas-Denton RN, Bertram JF (2011) Glomerular number and size variability and risk for kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 20:7–15

El Kares R, Manolescu DC, Lakhal-Chaieb L, Montpetit A, Zhang Z, Bhat PV, Goodyer P (2010) A human ALDH1A2 gene variant is associated with increased newborn kidney size and serum retinoic acid. Kidney Int 78:96–102

Zhang Z, Quinlan J, Hoy W, Hughson MD, Lemire M, Hudson T, Hueber PA, Benjamin A, Roy A, Pascuet E, Goodyer M, Raju C, Houghton F, Bertram J, Goodyer P (2008) A common RET variant is associated with reduced newborn kidney size and function. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:2027–2034

Miyazono K, Kamiya Y, Morikawa M (2010) Bone morphogenetic protein receptors and signal transduction. J Biochem 147:35–51

Bragdon B, Moseychuk O, Saldanha S, King D, Julian J, Nohe A (2011) Bone morphogenetic proteins: a critical review. Cell Signal 23:609–620

Di Giovanni V, Alday A, Chi L, Mishina Y, Rosenblum ND (2011) Alk3 controls nephron number and androgen production via lineage-specific effects in intermediate mesoderm. Development 138:2717–2727

Weber S, Taylor JC, Winyard P, Baker KF, Sullivan-Brown J, Schild R, Knüppel T, Zurowska AM, Caldas-Alfonso A, Litwin M, Emre S, Ghiggeri GM, Bakkaloglu A, Mehls O, Antignac C, Network E, Schaefer F, Burdine RD (2008) SIX2 and BMP4 mutations associate with anomalous kidney development. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:891–903

Capasso M, Ayala F, Russo R, Avvisati RA, Asci R, Iolascon A (2009) A predicted functional single-nucleotide polymorphism of bone morphogenetic protein-4 gene affects mRNA expression and shows a significant association with cutaneous melanoma in Southern Italian population. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 135:1799–1807

Böttcher Y, Unbehauen H, Klöting N, Ruschke K, Körner A, Schleinitz D, Tönjes A, Enigk B, Wolf S, Dietrich K, Koriath M, Scholz GH, Tseng YH, Dietrich A, Schön MR, Kiess W, Stumvoll M, Blüher M, Kovacs P (2009) Adipose tissue expression and genetic variants of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A gene (BMPR1A) are associated with human obesity. Diabetes 58:2119–2128

Zhang Z, Iglesias D, Eliopoulos N, El Kares R, Chu L, Romagnani P, Goodyer P (2011) A variant OSR1 allele which disturbs OSR1 mRNA expression in renal progenitor cells is associated with reduction of newborn kidney size and function. Hum Mol Genet 20:4167–4174

Kaczmarczyk M, Loniewska B, Kuprjanowicz A, Józwa A, Binczak-Kuleta A, Goracy I, Dawid G, Kordek A, Karpinska-Kaczmarczyk K, Brodkiewicz A, Ciechanowicz A (2012) An insertion/deletion ACE polymorphism and kidney size in Polish full-term newborns. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. doi:10.1177/1470320312448948

Mosteller RD (1987) Simplified calculation of body-surface area. N Engl J Med 317:1098

Schmidt IM, Main KM, Damgaard IN, Mau C, Haavisto AM, Chellakooty M, Boisen KA, Petersen JH, Scheike T, Olgaard K (2004) Kidney growth in 717 healthy children aged 0–18 months: a longitudinal cohort study. Pediatr Nephrol 19:992–1003

Vujic A, Kosutic J, Bogdanovic R, Prijic S, Milicic B, Igrutinovic Z (2007) Sonographic assessment of normal kidney dimensions in the first year of life—a study of 992 healthy infants. Pediatr Nephrol 22:1143–1150

Qiao J, Cohen D, Herzlinger D (1995) The metanephric blastema differentiates into collecting system and nephron epithelia in vitro. Development 121:3207–3214

James RG, Schultheiss TM (2005) Bmp signaling promotes intermediate mesoderm gene expression in a dose-dependent, cell-autonomous and translation-dependent manner. Dev Biol 288:113–125

Guo J, Wu G (2012) The signaling and functions of heterodimeric bone morphogenetic proteins. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 23:61–67

Hu MC, Piscione TD, Rosenblum ND (2003) Elevated SMAD1/beta-catenin molecular complexes and renal medullary cystic dysplasia in ALK3 transgenic mice. Development 130:2753–2766

Hartwig S, Bridgewater D, Di Giovanni V, Cain J, Mishina Y, Rosenblum ND (2008) BMP receptor ALK3 controls collecting system development. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:117–124

Sakurai H, Nigam SK (1998) In vitro branching tubulogenesis: implications for developmental and cystic disorders, nephron number, renal repair, and nephron engineering. Kidney Int 54:14–26

Hogan BL (1996) Bone morphogenetic proteins in development. Curr Opin Genet Dev 6:432–438

Cain JE, Bertram JF (2006) Ureteric branching morphogenesis in BMP4 heterozygous mutant mice. J Anat 209:745–755

Miyazaki Y, Oshima K, Fogo A, Hogan BL, Ichikawa I (2000) Bone morphogenetic protein 4 regulates the budding site and elongation of the mouse ureter. J Clin Invest 105:863–873

Ikeya M, Fukushima K, Kawada M, Onishi S, Furuta Y, Yonemura S, Kitamura T, Nosaka T, Sasai Y (2010) Cv2, functioning as a pro-BMP factor via twisted gastrulation, is required for early development of nephron precursors. Dev Biol 337:405–414

Reis LM, Tyler RC, Schilter KF, Abdul-Rahman O, Innis JW, Kozel BA, Schneider AS, Bardakjian TM, Lose EJ, Martin DM, Broeckel U, Semina EV (2011) BMP4 loss-of-function mutations in developmental eye disorders including SHORT syndrome. Hum Genet 130:495–504

Ramesh Babu L, Wilson SG, Dick IM, Islam FMA, Devine A, Prince RL (2005) Bone mass effects of a BMP4 gene polymorphism in postmenopausal women. Bone 36:555–561

Choudhry S, Avila PC, Nazario S, Ung N, Kho J, Rodriguez-Santana JR, Casal J, Tsai HJ, Torres A, Ziv E, Toscano M, Sylvia JS, Alioto M, Salazar M, Gomez I, Fagan JK, Salas J, Lilly C, Matallana H, Castro RA, Selman M, Weiss ST, Ford JG, Drazen JM, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Chapela R, Silverman EK, Burchard EG (2005) CD14 tobacco gene–environment interaction modifies asthma severity and immunoglobulin E levels in Latinos with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172:173–182

Berger M, Stassen HH, Köhler K, Krane V, Mönks D, Wanner C, Hoffmann K, Hoffmann MM, Zimmer M, Bickeböller H, Lindner TH (2006) Hidden population substructures in an apparently homogeneous population bias association studies. Eur J Hum Genet 14:236–244

Cordell HJ, Clayton DG (2005) Genetic association studies. Lancet 366:1121–1131

Łoniewska B, Clark JS, Kaczmarczyk M, Adler G, Binczak-Kuleta A, Kordek A, Horodnicka-Józwa A, Dawid G, Rudnicki J, Ciechanowicz A (2012) Possible counter effect in newborns of 1936A > G (I646V) polymorphism in the AKAP10 gene encoding A-kinase-anchoring protein 10. J Perinatol 32:230–234

IHC (2003) The International HapMap Project. Nature 426:789–796

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaczmarczyk, M., Goracy, I., Loniewska, B. et al. Association of BMPR1A polymorphism, but not BMP4, with kidney size in full-term newborns. Pediatr Nephrol 28, 433–438 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-012-2277-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-012-2277-7