Abstract

Bone is a dynamic tissue. Skeletal bone integrity is maintained through bone modeling and remodeling. The mechanisms underlying this bone mass regulation are complex and interrelated. An imbalance in the regulation of bone remodeling through bone resorption and bone formation results in bone loss. Chronic inflammation influences bone mass regulation. Inflammation-related bone disorders share many common mechanisms of bone loss. These mechanisms are ultimately mediated through the uncoupling of bone remodeling. Cachexia, physical inactivity, pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as iatrogenic factors related to effects of immunosuppression are some of the common mechanisms. Recently, cytokine signaling through the central nervous system has been investigated for its potential role in bone mass dysregulation in inflammatory conditions. Growing research on the molecular mechanisms involved in inflammation-induced bone loss may lead to more selective therapeutic targeting of these pathological signaling pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic inflammation influences bone mass regulation [1, 2]. The mechanisms underlying this bone mass regulation are complex and interrelated. Inflammation disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, share many common mechanisms but also have unique features of bone mass dysregulation [1–4]. These mechanisms are ultimately mediated through the regulation of bone modeling and remodeling cycle [5, 6].

Bone modeling and bone remodeling

Bone is a dynamic tissue designed to provide structural support and an important reservoir for mineral and hematopoietic cells [3]. Bone modeling adapts structure to loading by changing bone size and shape and so maintains bone strength [7]. Bone modeling is the sum of the activities of the endosteum and periosteum of bone to produce bone forms [8]. Bone modeling predominates during growth [9]. Bone formation and resorption are not coupled in time or space in skeletal modeling. This process results in an increase in bone diameter and modification of bone shape. Bone modeling results in new bone formed at a location different from the site of bone resorption [10]. Adolescence has been associated with accelerated bone maturation and bone modeling is responsible for approximately 40% of peak skeletal mass [11]. Bone modeling is important for changes in cortical geometry during growth. Peak bone mass occurs toward the end of the third decade of life [12].

On the other hand, bone remodeling (or bone metabolism) is a life-long process where old bone is removed from the skeleton and new bone is added. Remodeling is initiated by damage-induced osteocyte apoptosis, which signals the location of damage via the osteocyte-canalicular system to endosteal lining cells that form the canopy of a bone remodeling compartment [7]. These processes also replace bone during growth and following injuries like fractures but also micro-damage, which occurs during normal activity. Remodeling responds to functional demands of the mechanical loading. As a result, bone is added where needed and removed where it is not required. Molecular signaling within the bone remodeling compartment between precursors, mature cells, cells of the immune system, and products of the resorbed matrix titrate the birth, work, and lifespan of this remodeling machinery to either remove or form a net volume of bone.

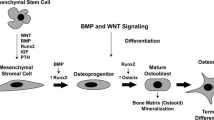

Bone modeling and remodeling processes are not very different at the cellular level. They are based on the separate actions of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. A full remodeling cycle is comprised of bone removal, or resorption, by osteoclasts followed by bone formation by osteoblasts, two processes that are tightly coupled. A schematic view of bone remodeling process is illustrated in Fig. 1. The active process of bone accumulation, or bone mass, is dependent on bone volume, height, and puberty in childhood [11]. The rate of bone remodeling is much higher in growing children [13]. In the first year of life, almost 100% of the skeleton is replaced. In adults, remodeling proceeds at about 10% per year. Both osteoclasts and osteoblasts are derived from their progenitors that reside in the bone marrow. Osteoclastogenesis is dependent on an adequate microenvironment, which provides essential signals such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANKL) and cytokines [7, 14]. Osteoblasts are cells of mesenchymal origin that are responsible for bone formation by secreting bone matrix proteins and promoting mineralization. Differentiated osteoblasts embedded in the bone matrix are termed osteocytes, and they have an important function within bone as mechanosensors and initiate bone remodeling [5]. Pre-osteoblasts express M-CSF and RANKL and can induce osteoclast formation, indicating the close interaction between bone formation and bone resorption [5, 14].

The bone remodeling process. Bone remodeling is a dynamic process in which old bone is removed and new bone is formed. It consists of two distinct stages—formation and resorption—that involves the activity of special cells termed osteoblasts and osteoclasts. a Mature mineralizing osteoblasts differentiate terminally into osteocytes. Osteocytes communicate with each other but also communicate with osteocytes through gap junctions and respond to changes in fluid flow arising from stress or mechanical stimulation. Important extrinsic anabolic signals, such as PTH, IGF-I, and mechanotransduction, stimulate bone formation whereas hypothalamic leptinergic signals transmitted through adrenergic nerves inhibit bone formation. Dietary intake of vitamin D influences calcium and phosphate metabolism and impacts the bone mineralization and formation. Bone formation is completed when the bone surface is restored and covered by a layer of protective bone cells called bone-lining cells. b Bone resorption. In this phase, osteoclasts act on the trabecular bone surface to erode the mineral and matrix. Osteoclasts are terminally differentiated bone-absorbing cells. Bone resorption is accomplished by a series of tightly orchestrated molecular and biochemical changes that eventually results in the creation of small cavities on the surface of the trabecular bone. The main switch for osteoclastic bone resorption is the RANK-L that is released by activated osteoblasts. Its action on the RANK receptor is regulated by OPG, which is also derived from osteoblasts. CNS central nervous system; IGF-I insulin-like growth-hormone I; OPG osteoprotegerin; PTH parathyroid hormone; RANK-L receptor activator for NF-κβ-ligand, SNS sympathetic nervous system

The identification of the RANKL-RANK-osteoprotegerin (OPG) system is a major breakthrough in bone biology. Disruption of the RANKL-RANK-OPG axis leads to the uncoupling of bone metabolism [2]. RANKL enhances differentiation of osteoclasts and their bone resorption capacity [15]. Several osteotropic factors, including vitamin D, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and prostaglandins promote the expression of RANKL [1, 2]. The Wnt genes encode a highly conserved class of signaling factors required for the development of musculoskeletal and neural structures. Wnt signaling is critical for bone mass accrual, bone remodeling, and fracture repair [1, 16–19].

Uncoupling of the bone remodeling cycle in chronic inflammatory disorders

Bone remodeling process regulates calcium homeostasis, repairs micro-damaged bones from everyday stress, and also shapes and ensures the mechanical integrity of the skeleton throughout life [3–5, 7]. An imbalance in the regulation of bone remodeling's two contrasting events, bone resorption and bone formation, results in bone loss. Chronic inflammatory diseases in children negatively influence skeletal health. Inflammation-associated bone loss can lead to growth retardation, reduced peak bone mass, and increased fracture risk [20]. Various mechanisms have been proposed for bone loss during inflammation [10]. The underlying disease process or therapeutic agents such as immunosuppressive therapies may influence bone cell function in inflammatory disorders.

Chronic inflammatory diseases are often associated with cachexia [21, 22]. Cachexia is associated with anorexia and reduced nutritional intake and negatively impacts bone mass [23]. Chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract reduces calorie intake and inhibits the absorption of nutrients important to bone metabolism [1]. Mildly elevated plasma homocysteine levels induced by vitamin B insufficiency deteriorate normal collagen cross-link formation, an important bone quality determinant [24, 25]. Furthermore, vitamin D deficiency is often prevalent in chronic inflammatory diseases [26]. Vitamin D deficiency reduces calcium and phosphorus absorption, increases PTH secretion, and enhances RANKL expression on osteoblasts [27]. Elevated expression of RANKL enhances bone resorption by promoting osteoclastogenesis. Vitamin D deficiency causes growth retardation and skeletal deformities in children [28]. In adults, vitamin D deficiency exacerbates osteopenia and osteoporosis, causes osteomalacia, and muscle weakness. Vitamin D can also modulate the immune response, and thus exerts an indirect role in inflammation-associated bone loss [29].

Physical immobility associated with chronic inflammatory conditions can lead to bone loss through reduced mechanical bone stimulation. Local or systemic inflammation causes pain, spasm, and decreased flexibility. Prolonged physical inactivity contributes to bone loss. Bone grows in response to the magnitude and direction of the forces to which it is subjected [10, 30]. This response keeps mechanically induced deformation of bone at a set point. Physical inactivity diminishes mechanical loads by influencing linear growth and muscle mass and may alter the functional muscle-bone set point [31]. The risk for hip fractures decreases as physical activity increases. Non-randomized trials have shown that exercise protects against bone loss [32].

Pro-inflammatory cytokines stimulate RANKL expression in osteoblasts. Enhanced production of RANKL promotes osteoclast differentiation and stimulates bone resorption activity of osteoclasts. TNF-α and IL-1 synergize with RANKL and stimulate bone resorption by osteoclasts [33, 34]. Rate of bone resorption is in equilibrium with the rate of bone formation during bone remodeling. Newly formed bone completely replaces the bone lost in the resorption phase. Inflammation may uncouple this tightly regulated bone remodeling cycle, resulting in negative bone balance. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1β promote the expression of calcium-sensing receptor and result in decreased circulating PTH and vitamin D levels [35, 36]. Anti-TNF-α therapy is very effective in treating patients with inflammatory disorders. This treatment improves the underlying condition but also appears to have an independent beneficial effect on bone, probably via the inhibition of osteoclastogenesis [1].

An additional mechanism by which inflammation uncouples bone remodeling cycle is through alternation of glucocorticoid signaling [1]. Glucocorticoids suppress inflammation and help to resolve underlying illness. However, glucocorticoid treatment has been associated with osteopenia in chronic inflammatory disease [37]. Glucocorticoids reduce osteoblast protein synthesis [38]. While glucocorticoids at physiological doses are essential for normal osteoblast differentiation [39], glucocorticoids at high doses diminish the number of osteoblasts by promoting apoptosis [40]. Glucocorticoids can also cause muscle wasting [41]. Glucocorticoid-induced myopathy may contribute to bone deficits via the functional muscle-bone unit. Recent studies suggest divergent effects of glucocorticoids on bone metabolism. There is currently debate in the pediatric bone field regarding the skeletal effects of glucocorticoids. Results suggested that children with oral corticosteroid treatment were at a greater risk of bone fracture, likely due to decreased bone formation [37]. Modest deficits in bone mineral content (BMC) in the lumbar spine but greater whole body BMC and femoral shaft dimensions were observed in pediatric patients with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome compared with controls [42]. In a follow-up study, glucocorticoids in childhood nephrotic syndrome were associated with low trabecular bone mineral density (BMD) but high cortical BMD and increased cortical dimensions were related to increased muscle mass [43].

Bone mass regulation in rheumatic diseases

Rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, the seronegative spondyloarthropathies including psoriatic arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus are all examples of rheumatic diseases in which inflammation is associated with skeletal pathology [44]. Although some of the mechanisms of skeletal remodeling are shared among these diseases, each disease has a unique impact on articular bone or on the axial or appendicular skeleton [45, 46]. Studies in human disease and in animal models of arthritis have identified the osteoclast as the predominant cell type mediating bone loss in arthritis [44, 47]. Many of the cytokines and growth factors implicated in rheumatic diseases have been demonstrated to impact osteoclast differentiation and function either directly, by acting on cells of the osteoclast-lineage, or indirectly, by acting on other cell types to modulate expression of the key molecules such as RANKL and its inhibitor OPG [48].

Reduced BMD and bone strength occurs in pediatric patients with rheumatoid arthritis [20, 49]. The hallmark of rheumatoid arthritis is inflammation of the synovium. The synovium becomes hyperplastic and inflamed, which is driven by innate and adaptive immune responses and subsequently invades the articular cartilage, causing bone erosions [50, 51]. Bone loss in the inflamed joint is also due to the uncoupling of bone remodeling. Pro-inflammatory cytokines released by activated immune cells in the inflamed joints promote osteoclast activity and bone erosion [1, 2, 51]. IL-17 recruits neutrophils to the inflamed joint and activates osteoclast differentiation by increasing the expression of RANK/RANKL in synoviocytes [52]. IL-17 also decreases the expression of OPG in osteoblastic cells, which promotes osteoclastogenesis and induces local bone erosion [53]. Other pivotal pro-inflammatory cytokines present in the arthritic joint include TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1, and IL-10 [54]. An additional pathway in which rheumatoid arthritis affects bone mass is through paracrine activity of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (11β-HSDs), potentially a major mechanism by which osteoblasts and osteoclasts are uncoupled [1]. Activities of 11β-HSDs were stimulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines, specifically IL-1 and TNF-α, suggesting that these factors might contribute to inflammation-mediated bone loss [55–58].

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the most common pediatric rheumatic disease [59] and affects joints in any part of the body. In this disease, the synovium and inflammation process can spread to surrounding tissues, eventually damaging cartilage and bone. Other areas of the body, especially the eyes, may also be affected by the inflammation. Without treatment, juvenile idiopathic arthritis can interfere with a child’s normal growth and development. Burnham et al. have evaluated the bone density, structure, and strength in 101 pediatrics patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis as compared to 830 healthy control subjects. Significant reduction in trabecular volumetric BMD and reduced bone strength was observed among those patients [20, 49, 60, 61]. Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis are at risk for deleterious alternations in cortical bone strength and trabecular bone density, placing them at greater risk of bone fracture. The pronounced bone deficits are greater than would be expected for their reductions in muscle cross-sectional area. Thus, bone alternations in juvenile idiopathic arthritis could represent a mixed defect of bone development and low muscle forces [49].

Bone mass regulation in inflammatory bowel disease

Low BMD is common in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [62, 63]. Poor nutrition, physical inactivity, exposure to glucocorticoids, decreased muscle mass, inflammatory cells, and cytokines all contribute to low BMD in inflammatory bowel disease. Nutritional supplementations have reversed growth impairment in patients with inflammatory bowel disorder and benefited bone mineralization [51]. Lean tissue mass correlated positively with lumbar spine and total body BMD. Increased lean tissue mass may be related to improved physical activity which in turn, may increase BMD in children with inflammatory bowel disease [51, 64–67]. Vitamin D deficiency may play a role in the pathological process of bone loss in inflammatory bowel disease. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels have been reported in patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease [68]. Soluble factors released by the inflamed intestine may impair bone formation [69]. Activated lymphocytes are present in the inflamed intestinal mucosa in inflammatory bowel disease. Activated lymphocytes and their secreted cytokines affect bone cell function. TNF-α and IFN-γ inhibit osteoblast formation and function, and TNF-α stimulates osteoclast formation via RANKL. Neutralization of TNF-α in patients with inflammatory bowel disease is associated with a rise in bone formation biomarkers and improved BMD [65, 70].

Sylvester et al. reported inconsistent findings with regard to biomarkers of bone resorption in pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease. Urinary N-telopeptides of collagen levels were decreased while urine deoxypyridinoline to creatinine ratios were not [71]. Possible reasons for the lack of elevated resorption markers in Crohn’s disease in the Sylvester’s study may be contributed to study design and analytic approach. Recent studies suggest that biomarkers of bone metabolism vary significantly with many confounding factors such as age, sex, and Tanner stage with a peak during the pubertal growth spurt followed by a rapid decline to adult levels [72–76]. After adjustment for these effects, Tuchman et al. reported that Crohn’s disease was associated with lower biomarkers of bone formation and greater bone resorption [66]. Beneficial anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids may offset some of its negative effects on bone. Dubner et al. carried out an elegant study in children with new-onset of Crohn’s disease. Their protocol was rigorously designed to adjust for numerous variables that may affect bone density, structure, or strength in the participants. In this study, glucocorticoid treatment was directly correlated with increased cortical BMD Z-score after 6 months, and the absence thereof with declines in cortical BMD in the subsequent 6 months [64]. The authors speculated that glucocorticoids may lead to a reduction in bone turnover, possibly causing reduced intracortical porosity, greater secondary mineralization, and higher cortical BMD. 11β-HSD1 is induced by inflammatory cytokines [1, 77]. Upregulation of 11β-HSD1 is documented in colonic mucosa in experimental colitis [78] and in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [79]. Un-regulation of 11β-HSD1 increases the sensitivity of the colon to therapeutic glucocorticoids [1, 80]. A high 11β-HSD1 activity in the inflamed colon may lead to more effective anti-inflammatory effects on the colon, enabling a lower level of glucocorticoids to be used. This could have a potential bone-sparing effect.

Bone mass regulation in chronic kidney disease

Reductions in BMD are common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and may increase susceptibility to low-trauma fracture [81, 82]. Multiple factors may attribute to decreased bone formation in chronic kidney disease (Fig. 2). A wide spectrum of skeletal manifestations may occur in CKD [83]. Renal osteodystrophy is important in CKD children because of the risk of long-term consequences such as growth retardation and bone deformalities [84, 85]. Growth failure is a significant problem in CKD [86]. Pediatric patients have unique problems because CKD profoundly interferes with bone growth and mineralization [87, 88]. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is associated with excessive bone resorption and high turnover bone disease whereas sub-optimal PTH levels may cause low turnover bone disease [89]. Recent findings suggest that inflammation negatively impacts bone mass in CKD. IL-6, the major mediator of the acute-phase inflammation, is elevated in CKD patients [90]. A number of factors such as hypertension, adiposity, insulin resistance, fluid overload, persistent infections, genetic variations of IL-6 gene, reduced renal function, and dialysis per se have been implicated in the pathogenesis of increased IL-6 levels in CKD [91, 92]. Increased circulatory levels of IL-6 may uncouple bone remodeling in end-stage renal disease (ESRD). IL-6 affects bone turnover independently of PTH. An inverse correlation between serum IL-6 and the bone turnover markers osteocalcin and β-isomerized C-terminal cross-linked peptide of collagen type I was documented in hemodialysis patients [93]. Indeed, calcitriol treatment affects bone remodeling by influencing the levels of plasma IL-6, beyond its suppressive effect on PTH [94]. IL-6, synthesized by osteoblasts in response to PTH, stimulates osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption in vitro, and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of bone loss in several inflammatory conditions. Increased serum IL-6 levels were associated with elevated bone resorption rate in uremic patients with renal osteodystrophy [95]. IL-6, released from human osteoblastic cells in the uremic milieu, has been implicated in the deranged bone turnover of uremic patients [96]. Osteoblastic IL-6 secretion was negatively associated with osteoblastic cell growth in dialysis patients with low bone turnover [97]. Increased expression of IL-1α, IL-6, TNF-α, and TGF-β has been demonstrated in bone marrow in ESRD patients. IL-6 and TGF-β were also detected in osteoblasts and osteocytes. The extent of cytokine deposition corresponded to the severity of renal osteodystrophy [98], suggesting an important role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of renal osteodystrophy. IL-6 exerts its action by binding to its receptor (IL6R) and transduces subsequent signaling within cells. In vitro as well as in vivo data point to IL-6 as an autocrine/paracrine factor in bone osteoclasts. Increased mRNA expression of IL-6 and IL6R was found in osteoclasts and bone marrow cells in iliac crest bone biopsies from ESRD patients [99]. Thus, chronic inflammation in CKD has a negative impact on bone remodeling. Pro-inflammatory cytokines may contribute to the pathogenesis of renal osteodystrophy.

Neuropeptides and bone mass regulation in chronic kidney disease

Cytokines signal through CNS and influence bone remodeling [100, 101]. Central to this hypothesis is the discovery that leptin is an important regulator of bone mass. The characterization of the sympathetic nervous system as a regulator of bone remodeling has led to several clinical studies demonstrating a substantial protective effect of ß-blockers, particularly ß1-blockers, on fracture risk [102]. Studies in several model organisms have reinforced the role of the CNS in the regulation of bone remodeling by the identification of several additional genes such as melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R), neuropeptide Y (NPY), Y2 receptor, cannabinoid receptor CB1 (Cnbr1), and the genes of the circadian clock [101]. These genes have several common features, including high levels of expression in the hypothalamus and the ability to regulate other major physiological functions in addition to bone remodeling including energy homeostasis, body weight, and reproduction.

Leptin plays a key role in skeletal physiology. Leptin-deficient (ob/ob), leptin receptor-deficient (db/db) and lipodystrophic mice, all of which exhibit decreased leptin signaling, have the same high bone mass phenotype [103]. Leptin is cleared from the circulation by the kidney [104, 105]. In CKD patients, serum levels of leptin were significantly increased [105, 106]. Elevated leptin level is a potent inhibitor of bone formation [100, 103]. High serum leptin levels are reported in several disorders, typically associated with osteopenia, such as liver cirrhosis, type 2 diabetes, and ESRD [107]. An inverse correlation between serum leptin levels and histomorphometric indicators of bone turnover has been demonstrated in renal bone disease. Serum leptin inversely correlated with PTH, bone formation rate, and mineral deposition rate in chronic dialysis patients. A complementary analysis in the same study in male dialysis patients revealed that the risk for low turnover bone disease increases with serum leptin concentrations. Adynamic bone disease is five times higher in patients with high serum leptin (third tertile) than those with relatively low serum leptin (first tertile) [108].

We demonstrated that elevated leptin levels may be an important cause of uremia-associated cachexia via signaling through the hypothalamic melanocortin system [109]. Leptin signaling is an important regulator of bone metabolism. Leptin acts centrally through the hypothalamic melanocortin receptors to affect appetite, metabolic rate, and bone mass [100]. Patients with loss-of-function mutations of melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) have markedly increased total body BMC and increased BMD [110], suggesting that leptin may regulate bone mass by increasing melanocortin receptor mediated signaling. We evaluated the role of leptin and melanocortin signaling on bone mass and bone strength in a mouse model of uremia. We showed that uremia induced in c57Bl/6J mice by subtotal nephrectomy resulted in elevated BUN, creatinine, and circulating leptin levels compared to pair-fed sham-operated mice. Whole-body and femoral BMC/BMD in nephrectomized c57Bl/6J mice were significantly lower than those in sham-operated mice. Femoral bone volume was markedly reduced in nephrectomized c57Bl/6J mice and this reduction was due to decreased cortical bone volume rather than cancellous bone volume. Cortical bone provides strength by being highly resistant to bending and torsion while cancellous bone has a vast surface area created by an interconnecting trabecular meshwork. The reduced femoral bone BMC/BMD and femoral cortical bone volume contributed to the observed reduction of femoral load to failure (a measure of bone strength and fracture risk) in nephrectomized c57Bl/6J mice. Agouti-related peptide (AgRP), a melanocortin receptor reverse agonist, was associated with increase in cortical bone volume but no change in cancellous bone volume as well as improved cortical bone strength [111]. These results in mice are consistent with clinical data from patients with CKD on dialysis in which decreases in cortical but not cancellous bone correlated with fracture risk. Hence, our results suggest that aberrant leptin signaling through melanocortin receptors may play an important role in the decreased bone mass and strength associated with CKD.

Neuropeptide Y (NPY) is a target of leptin signaling in the hypothalamus and functions through its receptors. Immunoreactivity of NPY is found in nerve fibers distributed throughout bone [112], strongly suggesting a role of NPY in the regulation of bone metabolism. NPY Y2-deficient mice display an increase in trabecular bone mass that can be reproduced by hypothalamus-specific deletion of Y2 gene [113], indicating that Y2 signaling in the hypothalamus inhibits bone formation. Recent studies indicate that signaling of Y2 receptor regulates, via a hypothalamic relay, the bone remodeling process in both femoral trabecular and cortical bone compartments [114]. Circulating levels of NPY are elevated in ESRD patients [115]. Whether the role of Y receptor and NPY signaling in bone metabolism is conserved from mouse to humans is unknown.

Conclusions

Chronic inflammatory diseases are characterized by systemic and local bone loss. The clinical picture is a composite of inflammatory lesions and structural damage, demonstrating the tight interaction between the immune and the skeletal system. Growing knowledge of the molecular mechanisms involved in the uncoupled bone metabolism has revealed potential targets for therapeutic interventions.

References

Hardy R, Cooper MS (2009) Bone loss in inflammatory disorders. J Endocrinol 201:309–320

Herman S, Kronke G, Schett G (2008) Molecular mechanisms of inflammatory bone damage, emerging targets for therapy. Trends Mole Medicine 14:245–253

Manolagas SC, Jilka RL (1995) Bone marrow, cytokines and bone remodeling. Emerging insights into the pathophysiology of osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 332:305–311

Schett G (2007) Joint remodeling in inflammatory disease. Ann Rheum Dis 66(S3):iii42–iii44

Sims NA, Gooi JH (2008) Bone remodeling: multiple cellular interactions required for coupling of bone formation and resorption. Seminars Cell Develop Biol 19:444–451

Teotelbaum SL (2000) Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science 289:1504–1508

Seeman E (2009) Bone modeling and remodeling. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 19:219–233

Parfitt AM (1982) The coupling of bone formation to bone resorption: a critical analysis of the concept and of its relevance to the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Metab Bone Dis Relat Res 4:1–6

Leonard MB (2003) Assessment of bone health in children and adolescents with cancer: promises and pitfalls of current techniques. Med Pediatr Oncol 41(3):198–207

Leonard MB (2007) Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in children: impact of the underlying disease. Pediatrics 119(S2):S166–S174

Bonjour JP, Theintz G, Buchs B, Slosman D, Rizzoli R (1991) Critical years and stages of puberty for spinal and femoral bone mass accumulation during adolescence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 73(3):555–563

Bonjour JP, Theintz G, Law F, Slosman D, Rizzoli R (1994) Peak bone mass. Osteoporos Int 4(Suppl 1):7–13

Rouster-Stevens KA, Klein-Gitelman MS (2005) Bone health in pediatric rheumatic disease. Curr Opin Pediatr 17(6):703–708

Matsuo K, Irie N (2008) Osteoclast-osteoblast communication. Arch Biochem Biophysis 473:201–209

Ogasawara T, Katagiri M, Yamamoto A, Hoshi K, Takato T, Nakamura K, Tanaka S, Okayama H, Kawaguchi H (2004) Osteoclast differentiation by RANKL requires NF-kappaB-mediated downregulation of cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (Cdk6). J Bone Miner Res 19(7):1128–1136

Hu H, Hilton MJ, Tu X, Yu K, Ornitz DM, Long F (2005) Sequential roles of Hedgehog and Wnt signaling in osteoblast development. Development 132:49–60

Polzer K, Diarra D, Zwerina J, Schett G (2008) Inflammation and destruction of the joints–the Wnt pathway. Joint Bone Spine 75:105–107

Diarra D, Stolina M, Polzer K, Zwerina J, Ominsky MS, Dwyer D, Korb A, Smolen J, Hoffmann M, Scheinecker C, van der Heide D, Landewe R, Lacey D, Richards WG, Schett G (2007) Dickkopf-1 is a master regulator of joint remodeling. Nat Med 13:156–163

Gong Y, Slee RB, Fukai N, Rawadi G, Roman-Roman S, Reginato AM, Wang H, Cundy T, Glorieux FH, Lev D, Zacharin M, Oexle K, Marcelino J, Suwairi W, Heeger S, Sabatakos G, Apte S, Adkins WN, Allgrove J, Arslan-Kirchner M, Batch JA, Beighton P, Black GC, Boles RG, Boon LM, Borrone C, Brunner HG, Carle GF, Dallapiccola B, De Paepe A, Floege B, Halfhide ML, Hall B, Hennekam RC, Hirose T, Jans A, Jüppner H, Kim CA, Keppler-Noreuil K, Kohlschuetter A, LaCombe D, Lambert M, Lemyre E, Letteboer T, Peltonen L, Ramesar RS, Romanengo M, Somer H, Steichen-Gersdorf E, Steinmann B, Sullivan B, Superti-Furga A, Swoboda W, van den Boogaard MJ, Van Hul W, Vikkula M, Votruba M, Zabel B, Garcia T, Baron R, Olsen BR, Warman ML, Osteoporosis-Pseudoglioma Syndrome Collaborative Group (2001) LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell 107:513–523

Burnham JM, Shults J, Weinstein R, Lewis JD, Leonard MB (2006) Childhood onset arthritis is associated with an increased risk of fracture: a population based study using the General Practice Research Database. Ann Rheum Dis 65(8):1074–1079

Cheung WW, Paik KH, Mak RH (2010) Inflammation and cachexia in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 25(4):711–724

Mak RH, Cheung W (2007) Cachexia in chronic kidney disease: role of inflammation and neuropeptide signaling. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 16(1):27–31

Strassburg S, Anker SD (2006) Metabolic and immunologic derangements in cardiac cachexia: where to from here? Heart Fail Rev 11(1):57–64

Saito M, Marumo K (2010) Collagen cross-links as a determinant of bone quality: a possible explanation for bone fragility in aging, osteoporosis, and diabetes mellitus. Osteoporos Int 21(2):195–214

Saito M, Shiraishi A, Ito M, Sakai S, Hayakawa N, Mihara M, Marumo K (2010) Comparison of effects of alfacalcidol and alendronate on mechanical properties and bone collagen cross-links of callus in the fracture repair rat model. Bone 46(4):1170–1179

Doorenbos CR, van den Born J, Navis G, de Borst MH (2009) Possible renoprotection by vitamin D in chronic renal disease: beyond mineral metabolism. Nat Rev Nephrol 5(12):691–700

Masuyama R, Stockmans I, Torrekens S, Van Looveren R, Maes C, Carmeliet P, Bouillon R, Carmeliet G (2006) Vitamin D receptor in chondrocytes promotes osteoclastogenesis and regulates FGF23 production in osteoblasts. J Clin Invest 116(12):3150–3159

Holick MF (2007) Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 357:266–281

Merlino LA, Curtis J, Mikuls TR, Cerhan JR, Criswell LA, Saag KG, Iowa Women's Health Study (2004) Vitamin D intake is inversely associated with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Iowa Women's Health Study. Arthritis Rheum 50:72–77

Rauch F, Schoenau E (2001) The developing bone: slave or master of its cells and molecules? Pediatr Res 50:309–314

Frost HM, Schönau E (2000) The “muscle-bone unit” in children and adolescents: a 2000 overview. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 13:571–590

Krølner B, Toft B, Pors Nielsen S, Tøndevold E (1983) Physical exercise as prophylaxis against involutional vertebral bone loss: a controlled trial. Clin Sci 64:541–546

Lam J, Takeshita S, Barker JE, Kanagawa O, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL (2000) TNF-alpha induces osteoclastogenesis by direct stimulation of macrophages exposed to permissive levels of RANK ligand. J Clin Invest 106:1481–1488

Zwerina J, Redlich K, Polzer K, Joosten L, Krönke G, Distler J, Hess A, Pundt N, Pap T, Hoffmann O, Gasser J, Scheinecker C, Smolen JS, van den Berg W, Schett G (2007) TNF-induced structural joint damage is mediated by IL-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:11742–11747

Canaff L, Zhou X, Hendy GN (2008) The proinflammatory cytokine, interleukin-6, up-regulates calcium-sensing receptor gene transcription via Stat1/3 and Sp1/3. Biol Chem 283(20):13586–13600

Canaff L, Hendy GN (2005) Calcium-sensing receptor gene transcription is up-regulated by the proinflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1beta. Role of the NF-kappaB PATHWAY and kappaB elements. J Biol Chem 280(14):14177–14188

Halton JM, Atkinson SA, Fraher L, Webber C, Gill GJ, Dawson S, Barr RD (1996) Altered mineral metabolism and bone mass in children during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Bone Miner Res 11:1774–1783

Reid IR (1998) Glucocorticoid effects on bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:1860–1862

Wong MM, Rao LG, Ly H, Hamilton L, Tong J, Sturtridge W, McBroom R, Aubin JE, Murray TM (1990) Long-term effects of physiologic concentrations of dexamethasone on human bone-derived cells. J Bone Miner Res 5:803–813

Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC (1998) Inhibition of osteoblastogenesis and promotion of apoptosis of osteoblasts and osteocytes by glucocorticoids. Potential mechanisms of their deleterious effects on bone. J Clin Invest 102:274–282

Seene T (1994) Turnover of skeletal muscle contractile proteins in glucocorticoid myopathy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 50:1–4

Leonard MB, Feldman HI, Shults J, Zemel BS, Foster BJ, Stallings VA (2004) Long-term, high-dose glucocorticoids and bone mineral content in childhood glucocorticoid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. N Engl J Med 351:868–875

Wetzsteon RJ, Shults J, Zemel BS, Gupta PU, Burnham JM, Herskovitz RM, Howard KM, Leonard MB (2009) Divergent effects of glucocorticoids on cortical and trabecular compartment BMD in childhood nephrotic syndrome. J Bone Miner Res 24(3):503–513

Walsh NC, Crotti TN, Goldring SR, Gravallese EM (2005) Rheumatic diseases: the effects of inflammation on bone. Immunol Rev 208:228–251

Ginaldi L, Di Benedetto MC, De Martinis M (2005) Osteoporosis, inflammation and ageing. Immun Ageing 2:14

Campisi G, Chiappelli M, De Martinis M, Franco V, Ginaldi L, Guiglia R, Licastro F, Lio D (2009) Pathophysiology of age-related diseases. Immun Ageing 6:12

van den Berg WB (2009) Lessons from animal models of arthritis over the past decade. Arthritis Res Ther 11(5):250

Yen ML, Tsai HF, Wu YY, Hwa HL, Lee BH, Hsu PN (2008) TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) induces osteoclast differentiation from monocyte/macrophage lineage precursor cells. Mol Immunol 45(8):2205–2213

Burnham JM, Shults J, Dubner SE, Sembhi H, Zemel BS, Leonard MB (2008) Bone density, structure, and strength in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: importance of disease severity and muscle deficits. Arthritis Rheum 58(8):2518–2527

Fournier C (2005) Where do T cells stand in rheumatoid arthritis? Joint Bon Spine 72:527–532

Viswanathan A, Sylvester FA (2008) Chronic pediatric inflammatory disease: effects on bone. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 9:107–122

McKenzie BS, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ (2006) Understanding the IL-23-IL-17 immune pathway. Trends Immunol 27:17–23

Kotake S, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Matsuzaki K, Itoh K, Ishiyama S, Saito S, Inoue K, Kamatani N, Gillespie MT, Martin TJ, Suda T (1999) IL-17 in synovial fluids from patients with rheumatoid arthritis is a potent stimulator of osteoclastogenesis. J Clin Invest 103:1345–1352

Hata H, Sakaguchi N, Yoshitomi H, Iwakura Y, Sekikawa K, Azuma Y, Kanai C, Moriizumi E, Nomura T, Nakamura T, Sakaguchi S (2004) Distinct contribution of IL-6, TNF-alpha, IL-1, and IL-10 to T cell-mediated spontaneous autoimmune arthritis in mice. J Clin Invest 114(4):582–588

Bland R, Worker CA, Noble BS, Eyre LJ, Bujalska IJ, Sheppard MC, Stewart PM, Hewison M (1999) Characterization of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity and corticosteroid receptor expression in human osteosarcoma cell lines. J Endocrinol 161:455–464

Eyre LJ, Rabbitt EH, Bland R, Hughes SV, Cooper MS, Sheppard MC, Stewart PM, Hewison M (2001) Expression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in rat osteoblastic cells: pre-receptor regulation of glucocorticoid responses in bone. J Cell Biochem 81:453–462

Cooper MS, Walker EA, Bland R, Fraser WD, Hewison M, Stewart PM (2000) Expression and functional consequences of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity in human bone. Bone 27:375–381

Cooper MS, Bujalska I, Rabbitt E, Walker EA, Bland R, Sheppard MC, Hewison M, Stewart PM (2001) Modulation of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isozymes by proinflammatory cytokines in osteoblasts: an autocrine switch from glucocorticoid inactivation to activation. J Bone Miner Res 16:1037–1044

Bowyer S, Roettcher P (1996) Pediatric rheumatology clinic populations in the United States: results of a 3-year survey. Pediatric Rheumatology Database Research Group. J Rheumatol 23:1968–1974

Burnham JM, Shults J, Petit MA, Semeao E, Beck TJ, Zemel BS, Leonard MB (2007) Alterations in proximal femur geometry in children treated with glucocorticoids for Crohn disease or nephrotic syndrome: impact of the underlying disease. J Bone Miner Res 22(4):551–559

Burnham JM, Shults J, Semeao E, Foster BJ, Zemel BS, Stallings VA, Leonard MB (2005) Body-composition alterations consistent with cachexia in children and young adults with Crohn disease. Am J Clin Nutr 82(2):413–420

Khadgawat R, Makharia GK, Puri K (2008) Evaluation of bone mineral density among patients with inflammatory bowel disease in a tertiary care setting in India. Indian J Gastroenterol 27(3):103–106

Smith J, Lidofsky S (2009) Bone disease in the inflammatory bowel disease population. Med Health R I 92(4):125–127

Dubner SE, Shults J, Baldassano RN, Zemel BS, Thayu M, Burnham JM, Herskovitz RM, Howard KM, Leonard MB (2009) Longitudinal assessment of bone density and structure in an incident cohort of children with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 136(1):123–130

Thayu M, Leonard MB, Hyams JS, Crandall WV, Kugathasan S, Otley AR, Olson A, Johanns J, Marano CW, Heuschkel RB, Veereman-Wauters G, Griffiths AM, Baldassano RN, Reach Study Group (2008) Improvement in biomarkers of bone formation during infliximab therapy in pediatric Crohn's disease: results of the REACH study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 6(12):1378–1384

Tuchman S, Thayu M, Shults J, Zemel BS, Burnham JM, Leonard MB (2008) Interpretation of biomarkers of bone metabolism in children: impact of growth velocity and body size in healthy children and chronic disease. J Pediatr 153(4):484–490

Boot AM, Bouquet J, Krenning EP, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM (1998) Bone mineral density and nutritional status in children with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 42:188–194

Silvennoinen J (1996) Relationships between vitamin D, parathyroid hormone and bone mineral density in inflammatory bowel disease. J Intern Med 239:131–137

Varghese S, Wyzga N, Griffiths AM, Sylvester FA (2002) Effects of serum from children with newly diagnosed Crohn disease on primary cultures of rat osteoblasts. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 35:641–648

Thayu M, Shults J, Burnham JM, Zemel BS, Baldassano RN, Leonard MB (2007) Gender differences in body composition deficits at diagnosis in children and adolescents with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 13(9):1121–1128

Sylvester FA, Davis PM, Wyzga N, Hyams JS, Lerer T (2006) Are activated T cells regulators of bone metabolism in children with Crohn disease? J Pediatr 148(4):461–466

Rauchenzauner M, Schmid A, Heinz-Erian P, Kapelari K, Falkensammer G, Griesmacher A, Finkenstedt G, Högler W (2007) Sex- and age-specific reference curves for serum markers of bone turnover in healthy children from 2 months to 18 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92(2):443–449

Weaver CM, Peacock M, Martin BR, McCabe GP, Zhao J, Smith DL, Wastney ME (1979) Quantification of biochemical markers of bone turnover by kinetic measures of bone formation and resorption in young healthy females. J Bone Miner Res 12(10):1714–1720

Blumsohn A, Hannon RA, Wrate R, Barton J, al-Dehaimi AW, Colwell A, Eastell R (1994) Biochemical markers of bone turnover in girls during puberty. Clin Endocrinol 40(5):663–670

Rotteveel J, Schoute E, Delemarre-van de Waal HA (1997) Serum procollagen I carboxyterminal propeptide (PICP) levels through puberty: relation to height velocity and serum hormone levels. Acta Paediatr 86(2):143–147

Tobiume H, Kanzaki S, Hida S, Ono T, Moriwake T, Yamauchi S, Tanaka H, Seino Y (1997) Serum bone alkaline phosphatase isoenzyme levels in normal children and children with growth hormone (GH) deficiency: a potential marker for bone formation and response to GH therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82(7):2056–2061

Hardy RS, Filer A, Cooper MS, Parsonage G, Raza K, Hardie DL, Rabbitt EH, Stewart PM, Buckley CD, Hewison M (2006) Differential expression, function and response to inflammatory stimuli of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in human fibroblasts: a mechanism for tissue-specific regulation of inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther 8:R108

Bryndová J, Zbánková S, Kment M, Pácha J (2004) Colitis up-regulates local glucocorticoid activation and down-regulates inactivation in colonic tissue. Scand J Gastroenterol 39:549–553

Stegk JP, Ebert B, Martin HJ, Maser E (2009) Expression profiles of human 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases type 1 and type 2 in inflammatory bowel diseases. Mol Cell Endocrinol 301:104–108

Czock D, Keller F, Rasche FM, Häussler U (2005) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of systemically administered glucocorticoids. Clin Pharmacokinet 44(1):61–98

Taal MW, Masud T, Green D, Cassidy MJ (1999) Risk factors for reduced bone density in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Tranplant 14:1922–1928

Atsumi K, Kushida K, Yamazaki K, Shimizu S, Ohmura A, Inoue T (1999) Risk factors for vertebral fractures in renal osteodystrophy. Am J Kidney Dis 33:287–293

Moe S, Drüeke T, Cunningham J, Goodman W, Martin K, Olgaard K, Ott S, Sprague S, Lameire N, Eknoyan G, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) (2006) Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 69:1945–1953

Klaus G, Watson A, Edefonti A, Fischbach M, Rönnholm K, Schaefer F, Simkova E, Stefanidis CJ, Strazdins V, Vande Walle J, Schröder C, Zurowska A, Ekim M, European Pediatric Dialysis Working Group (EPDWG) (2006) Prevention and treatment of renal osteodystrophy in children on chronic renal failure: European guidelines. Pediatr Nephrol 21:151–159

Wong H, Mylrea K, Feber J, Drukker A, Filler G (2006) Prevalence of complications in children with chronic kidney disease according to KDOQI. Kidney Int 70:585–590

Fivush BA, Jabs K, Neu AM, Sullivan EK, Feld L, Kohaut E, Fine R (1998) Chronic renal insufficiency in children and adolescents: the 1996 annual report of NAPRTCS. North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study. Pediatr Nephrol 12:328–337

Salusky IB, Kuizon BG, Jüppner H (2004) Special aspects of renal osteodystrophy in children. Semin Nephrol 24:69–77

Sanchez CP, Kuizon BD, Abdella PA, Jüppner H, Salusky IB, Goodman WG (2000) Impaired growth, delayed ossification, and reduced osteoclastic activity in the growth plate of calcium-supplemented rats with renal failure. Endocrinology 141:1536–1544

Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Chapuy MC, Delmas PD (1996) Increased bone turnover in late postmenopausal women is a major determinant of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 11:337–349

Carrero JJ, Ortiz A, Qureshi AR, Martín-Ventura JL, Bárány P, Heimbürger O, Marrón B, Metry G, Snaedal S, Lindholm B, Egido J, Stenvinkel P, Blanco-Colio LM (2009) Additive effects of soluble TWEAK and inflammation on mortality in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4:110–118

Stenvinkel P, Ketteler M, Johnson RJ, Lindholm B, Pecoits-Filho R, Riella M, Heimbürger O, Cederholm T, Girndt M (2005) IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-alpha: central factors in the altered cytokine network of uremia–the good, the bad, and the ugly. Kidney Int 67:1216–1233

Stenvinkel P, Pecoits-Filho R, Lindholm B, for the DialGene Consortium (2005) Gene polymorphism association studies in dialysis: the nutrition-inflammation axis. Semin Dial 18:322–330

Eleftheriadis T, Kartsios C, Antoniadi G, Kazila P, Dimitriadou M, Sotiriadou E, Koltsida M, Golfinopoulos S, Liakopoulos V, Christopoulou-Apostolaki M (2008) The impact of chronic inflammation on bone turnover in hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail 30:431–437

Türk S, Akbulut M, Yildiz A, Gürbilek M, Gönen S, Tombul Z, Yeksan M (2002) Comparative effect of oral pulse and intravenous calcitriol treatment in hemodialysis patients: the effect on serum IL-1 and IL-6 levels and bone mineral density. Nephron 90:188–194

Montalbán C, García-Unzueta MT, De Francisco AL, Amado JA (1999) Serum interleukin-6 in renal osteodystropgy: relationship with serum PTH and bone remodeling markers. Horm Metab Res 31:14–17

Steddon SJ, McIntyre CW, Schroeder NJ, Burrin JM, Cunningham J (2004) Impaired release of interleukin-6 from human osteoblastic cells in the uraemic milieu. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19:3078–3083

Sánchez MC, Bajo MA, Selgas R, Mate A, Sánchez-Cabezudo MJ, López-Barea F, Esbrit P, Martínez ME (2001) Cultures of human osteoblastic cells from dialysis patients: influence of bone turnover rate on in vitro selection of interleukin-6 and osteoblastic cell makers. Am J Kidney Dis 37:30–37

Duarte ME, Carvalho EF, Cruz EA, Lucena SB, Andress DL (2002) Cytokine accumulation in osteitis fibrosa of renal osteodystrophy. Braz J Med Biol Res 35:25–29

Langub MC Jr, Koszewski NJ, Turner HV, Monier-Faugere MC, Geng Z, Malluche HH (1996) Bone resorption and mRNA expression of IL-6 and IL-6 receptor in patients with renal osteodystrophy. Kidney Int 50:515–520

Karsenty G (2006) Convergence between bone and energy homeostasis: leptin regulation of bone mass. Cell Metab 4:341–348

Lieben L, Callewaert F, Bouillon R (2009) Bone and metabolism: a complex crosstalk. Horm Res 71(S1):134–138

Baek K, Bloomfield SA (2009) Beta-adrenergic blockade and leptin replacement effectively mitigate disuse bone loss. J Bone Miner Res 24:792–799

Ducy P, Amling M, Takeda S, Priemel M, Schilling AF, Beil FT, Shen J, Vinson C, Rueger JM, Karsenty G (2000) Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: a central control of bone mass. Cell 100:197–207

Cumin F, Baum HP, Levens N (1996) Leptin is cleared from the circulation primarily by the kidney. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 20:112–126

Sharma K, Considine RV, Michael B, Dunn SR, Weisberg LS, Kurnik BR, Kurnik PB, O'Connor J, Sinha M, Caro JF (1997) Plasma leptin is partly cleared by the kidney and is elevated in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 51:1980–1985

Daschner M, Tönshoff B, Blum WF, Englaro P, Wingen AM, Schaefer F, Wühl E, Rascher W, Mehls O (1998) Inappropriate elevate of serum leptin levels in children with chronic renal failure. European Study Group for Nutritional Treatment of Chronic Renal Failure in Childhood. J Am Soc Nephrol 9:1074–1079

Brown SA, Rosen CJ (2003) Osteoporosis. Med Clin North Am 87:1039–1063

Coen G, Ballanti P, Fischer MS, Balducci A, Calabria S, Colamarco L, Di Zazzo G, Lifrieri F, Manni M, Sardella D, Nofroni I, Bonucci E (2003) Serum leptin in dialysis renal osteodystrophy. Am J Kidney Dis 42:1036–1042

Cheung W, Yu PX, Little BM, Cone RD, Marks DL, Mak RH (2005) Role of leptin and melanocortin signaling in uremia-associated cachexia. J Clin Invest 115:1659–1665

Farooqi IS, Yeo GS, Keogh JM, Aminian S, Jebb SA, Butler G, Cheetham T, O'Rahilly S (2000) Dominant and recessive inheritance of morbid obesity associated with melanocortin 4 receptor deficiency. J Clin Invest 106:271–279

Cheung W, Vanek C, Iwaniec UT, Turner RT, Klein RF, Mak RH (2007) A novel hypothalamic mechanism in uremic bone disease. Abstract, 39th Annual Meeting American Society of Nephrology, SA-FC006, November 1st-4th, San Francisco, California, USA

Bjurholm A, Kreicbergs A, Terenius L, Goldstein M, Schultzberg M (1988) Neuropeptide Y-, tyrosine hydroxylase- and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-immunoreactive nerves in bone and surrounding tissues. Auton Nerv Syst 25:119–125

Baldock PA, Sainsbury A, Couzens M, Enriquez RF, Thomas GP, Gardiner EM, Herzog H (2002) Hypothalamic Y2 receptors regulate bone formation. J Clin Invest 109:915–921

Patel MS, Elefterios F (2007) The new field of neuroskeletal biology. Calf Tissue Int 80:337–347

Adu-Zikri N, El-Fattah AA, Raafat M, Ismail L, Yahya A, Ahmed A, El-Sadek SA, El-Shamaa A, El-Sheikh N (2009) Study of neuropeptide Y and its relation to the cardiovascular complications in end stage renal disease. World J Med Sci 4:22–32

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Amgen Young Investigator Grant of the National Kidney Foundation to W.W.C. and grants from the National Institute of Health (K24 DK59574), Baxter Renal Discovery Program, and the Satellite Foundation to R.H.M. We thank Dr. Mary B. Leonard, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine for valuable discussions and critical review of this manuscript.

Disclosure of interests

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists. RHM is supported by NIHU01 DK-03-012. WWC is supported by a young investigator award from the National Kidney Foundation.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheung, W.W., Zhan, JY., Paik, K.H. et al. The impact of inflammation on bone mass in children. Pediatr Nephrol 26, 1937–1946 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-010-1733-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-010-1733-5