Abstract

We present high order surface finite element methods for the linear analysis of seven-parameter shells. The special feature of these methods is that they work with the exact geometry of the shell reference surface which can be given parametrically by a global map or implicitly as the zero level-set of a level set function. Furthermore, a special treatment of singular parametrizations is proposed. For the approximation of the shell displacement parameters we have implemented arbitrary order hierarchical shape functions on quadrilateral and triangular meshes. The methods are verified by a convergence analysis in numerical experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Due to their efficient load-carrying capabilities, shell structures enjoy widespread use in a variety of engineering applications. Therefore, a huge amount of research work has been devoted to the development of shell models (e.g. [11, 15]), their formal justification (e.g. [12,13,14]), as well as to the realization of numerical methods (e.g. [8, 9]). It is well known that shell structures are sensitive to geometric imperfections [30]. Even worse, the approximation of the geometry leads to wrong solutions in some situations, see the plate paradox investigated e.g. in [2]. Furthermore, e.g., in contact problems an exact description of smooth geometries is of interest. Among others, these examples motivated us to develop shell finite element methods based on the exact geometry. Therefore, the literature review concentrates on geometry representation.

Usually, the exact geometry is approximated. In the simplest case, planar facet elements are deployed. However, those elements can only poorly represent curved structures and are not reliable due to a missing bending–stretching coupling on the element level. In order to represent the geometry more accurately high order (often quadratic) shape functions are used. To our best knowledge, exact geometry methods for shell analysis are restricted to the case where the exact geometry is parametrically defined. A finite element method which allows for arbitrary parametrizations is described in [1]. Therein, the field approximation based on Lagrange elements is applied to a seven-parameter shell theory considering geometrical nonlinearities and functionally graded shells. However, the actual computation of the arising integrals is carried out by symbolic algebra subroutines written in MAPLE. In [31], an exact geometry method based on the blending function method is presented. Furthermore, in the work [29] a finite element method for geometrically nonlinear problems is developed. Therein, the exact geometry of the shell is captured by an initial deformation of a flat reference configuration. However, since most CAD systems use NURBS functions, it is reasonable to restrict the input parametrizations for the shell analysis to NURBS [10]. This has the advantage that the parametrization is given as a product of basis functions and coefficients. Thus, derivatives are easily computed if the derivatives of the basis functions are known. Following the concept of Isogemetric Analysis, shell finite elements based on different shell models were proposed in [5, 23, 24, 28] among others. Therein, the reference surface is described by NURBS, just as the field approximation.

Shell problems can also be seen as one application of the more general concept of partial differential equations defined on surfaces. We mention [17] for an overview of related finite element methods. To our best knowledge the first exact geometry method for the Laplace–Beltrami operator on implicitly defined surfaces was presented in [16]. Therein, the exact geometry of closed smooth surfaces is parametrized over a space triangulation by means of the closest point projection. Recently, a directional mapping based on predefined search directions was considered to construct high order geometry approximations [20, 25]. In [22], the search direction has been tailored such that the exact geometry of smooth surfaces with boundaries is available in the finite element analysis.

In the present paper we consider shells with parametrically and implicitly defined reference surfaces. For both cases exact geometry finite element methods are presented. For implicitly defined shells the reference surface is parametrized over a space triangulation following the developments presented in [22]. Thus, the implicit setting is reformulated to the parametrized setting. The curvature of the reference surface is necessary within the considered variational formulation, and so are the second order partial derivatives of the parametrization. In the case of a parametrically defined surface they are obtained by automatic differentiation based on hyper-dual numbers [19]. For the case of an implicitly defined surface, we derive a formula such that only the second order derivatives of the level-set function \(\phi \) are needed. As a shell model we use a displacement based seven-parameter model accounting for stretching, bending, shear deformations, and through-the-thickness stretching (see [1, 7, 15]). We restrict ourselves to a linear elastic analysis, i.e. small displacements, small rotations, small strains, and Hooke’s law. The discretization of the shell deformation is done by means of high order hierarchical \(H^1\)-conforming shape functions. Our implementation allows for arbitrary polynomial orders. Since our formulation is displacement based, various locking phenomena (membrane, shear and thickness locking) occur, which can be seen in the examples in Sect. 4. Therefore, the low order methods are very inefficient. Albeit the presence of locking effects, the proposed methods converge to correct solutions. Using high order shape functions reduces the locking effects and offers high convergence rates. Nevertheless, in many practical examples this approach might be not very efficient, see e.g. [29] for a quadratic element with a efficient displacement based formulation. As a further novelty, we propose a strategy for the modification of the shape functions to tackle singular parametrizations where the determinant of the metric vanishes on some part of the geometry. Following a similar strategy developed in the context of Isogeometric Analysis [33], we modify the ansatz space by combining and skipping basis functions.

2 Differential geometry and shell model

In this section, we recall the differential geometry of thin-walled structures and introduce the displacement based seven-parameter shell model. First, the geometry of the reference surface is presented. Then, the reference surface is extended to the three-dimensional shell volume, for which we present the geometric relations. In a next step, the three-dimensional shell problem is introduced. Finally, the kinematics are restricted to a seven-parameter shell model. We remark that the differential geometry in the context of thin-walled structures is exhaustively discussed in [3] and [11], among others.

The underlying assumption in shell analysis is that the computational domain \(\varOmega \subset \mathbb {R}^3\) has a small extension in one coordinate compared to the two others. Thus, we assume that \(\varOmega \) is located around a two-dimensional reference surface \({\bar{\varOmega }}\).

2.1 Reference surface

In the present paper, we consider shell reference surfaces which are given parametrically or implicitly. In the former case we have a parametrization \(\overline{\mathfrak {g}}:\;{\bar{U}}\subset \mathbb {R}^2 \rightarrow {\bar{\varOmega }}\) available with given \({\bar{U}}\). In the latter case, the reference surface is given as the zero-level set of a function \(\phi : \mathbb {R}^3 \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) inside a cuboid \(B\)

For this setting, the normal vector to the surface is given by

In the numerical method, we will make use of a piecewise parametrization of the exact surface over a space triangulation. Therefore, the implicit description of the reference surface is turned into a parametric one. Thus, we consider the differential geometry of a parametrized surface in the rest of this section.

Given the parametrization \(\overline{\mathfrak {g}}\), we can define the two covariant base vectors \(\mathbf {\overline{G}}_{\alpha }:=\frac{\partial \overline{\mathfrak {g}} }{\partial \theta ^\alpha } \), which span the tangent plane to \({\bar{\varOmega }}\). Here and in the following, Greek indices take the values 1 and 2 and Latin indices the values 1, 2, 3. With the base vectors we can define the unit normal vector

and the covariant coefficients of the metric \(\overline{G}_{\alpha \beta } = \mathbf {\overline{G}}_{\alpha }\, \cdot \, \mathbf {\overline{G}}_{\beta }\). The contravariant coefficients of the metric are given by \([\overline{G}^{\alpha \beta }]=[\overline{G}_{\alpha \beta }]^{-1}\), where \([\overline{G}_{\alpha \beta }]\) is the coefficient matrix. The contravariant base vectors can than be computed by \(\mathbf {\overline{G}}^{\alpha }= \overline{G}^{\alpha \beta } \mathbf {\overline{G}}_{\beta }\). Here, and in the following, the Einstein summation convention applies. Whenever an index occurs once in an upper position and in a lower position we sum over this index. Due to the definition of the normal vector as a unit vector, we have \(\mathbf {n}\, \cdot \, \mathbf {n}=1\). Taking the derivative with respect to \(\theta ^\alpha \), yields \(\frac{\partial }{\partial \theta ^\alpha } (\mathbf {n}\cdot \mathbf {n}) = \mathbf {n}_{,\alpha } \cdot \mathbf {n}+ \mathbf {n}\cdot \mathbf {n}_{,\alpha } = 0\). Thus, the derivatives of the normal vector are in the tangent plane of the surface. Expressing the derivatives of the normal vector trough a linear combination of the tangent vectors yields

with

These relations are known as the Weingarten equations, first established in [34]. The functions \(h_{\alpha \beta }=h_{\beta \alpha }\) are the coefficients of the second fundamental form. Furthermore, \(H=\frac{1}{2} h_\gamma ^\gamma \) is the mean curvature and \(K = h_1^1 h_2^2-h_1^2 h_2^1\) is the Gaussian curvature of the surface.

2.2 Geometry of the shell volume

In this section, we assume that we have a parametrization \(\overline{\mathfrak {g}}\) of the reference surface \({\bar{\varOmega }}\) available. Then the parametrization of the shell volume \(\varOmega \) is given by

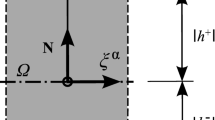

with the interval \(T=[-\nicefrac {t}{2},\nicefrac {t}{2}]\), where t is the thickness of the shell. The geometric setting is illustrated in Fig. 1. The first two base vectors in the shell volume are related to the base vectors at the reference surface by

where \(\mu _{\alpha }^{\beta } =\left( \delta _{\alpha }^{\beta } - \theta ^3 h_{\alpha }^{\beta } \right) \) are the components of the shifter tensor and \(\delta _\alpha ^\beta \) is the Kronecker delta. Furthermore, \(\mathbf {G}_{3} = \mathbf {n}\). Thus, the covariant components of the metric are given by

and the determinant of the metric is

The components of the contravariant metric are

where

is the adjugate matrix of \([\overline{G}_{\alpha \beta }]\).

2.3 The 3D shell problem

We continue with the statement of the three-dimensional shell problem, which is considered in the present paper to be a problem of linearized elasticity on shell-like domains \(\varOmega \) with boundary \(\varGamma \). The three-dimensional elasticity problem reads: Find \({\tilde{{\mathbf {u}}}}: \varOmega \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^3\) such that

Here, \({\tilde{\pmb {\sigma }}}\) is the stress tensor, \({\tilde{{\mathbf b}}}\) the bodyforce, \({\tilde{\mathbb {C}}}\) the elasticity tensor, \({\tilde{\pmb {\epsilon }}}\) the strain tensor, \({\tilde{{\mathbf {u}}}}_D\) the given Dirichlet datum on \(\varGamma _D\), and \({\tilde{{\mathbf t}}}_N\) the given Neumann datum on \(\varGamma _N\). We require that \(\varGamma = \varGamma _D \,\cup \,\varGamma _N\) and \(\varGamma _D \,\cap \,\varGamma _N = {\emptyset }\). Moreover, we assume that \(\varGamma _D\) is a subset of the lateral part of the boundary \(\varGamma \). We remark that all quantities with a tilde over them are defined on \(\varOmega \) without reference to a specific parametrization. Furthermore, we have the following coordinate-free displacement-based variational formulation of (12): Find \({\tilde{{\mathbf {u}}}}\in V\) such that

with \(V=\{{\tilde{{\mathbf {u}}}} \in [H^1(\varOmega )]^3\;|\;{\tilde{{\mathbf {u}}}}={\tilde{{\mathbf {u}}}}_D \;\text {on}\; \varGamma _D \}\) and \(V_0=\{{\tilde{\mathbf{v}}} \in [H^1(\varOmega )]^3\;|\;{\tilde{\mathbf{v}}} = 0 \;\text {on}\; \varGamma _D \}\).

In order to solve (13), we rewrite the problem in parametric coordinates. Instead of solving for \({\tilde{{\mathbf {u}}}}(\mathbf {x}),\mathbf {x} \in \varOmega \), we seek the displacement field \({\mathbf {u}}(\theta ^1,\theta ^2,\theta ^3) = {\tilde{{\mathbf {u}}}}(\mathfrak {g}(\theta ^1,\theta ^2,\theta ^3))\) defined on the parametric space. This change of variables applies to all quantities analogously. In the present paper, we employ a linear isotropic material law, where the contravariant components of the elasticity tensor \(\mathbb {C}=\mathbb {C}^{ijkl}\;\mathbf {G}_{i} \otimes \mathbf {G}_{j} \otimes \mathbf {G}_{k} \otimes \mathbf {G}_{l}\) for a shell-like body are given by

The Lamé constants are denoted with \(\lambda \) and \(\mu \).

2.4 Seven-parameter shell model

Up to this point, no approximation of the three-dimensional problem has been introduced. In this section, we introduce the seven-parameter shell model [1, 7, 15] by restricting the through-the-thickness kinematics of the shell to be of the form

where we made use of the following through-the-thickness functions

In (15), we have introduced the seven parameters \(\overset{(1)}{u_i}(\theta ^1,\theta ^2)\), \(\overset{(2)}{u_i}(\theta ^1,\theta ^2)\), and \(\overset{(n)}{u}(\theta ^1,\theta ^2)\), which depend only on the position on the reference surface. While \(\overset{(1)}{u_i}\) physically represent the Cartesian components of the displacement vector at the bottom surface (at \(\theta ^3=-\nicefrac {t}{2}\)), \(\overset{(2)}{u_i}\) represent the Cartesian components of the displacement vector at the top surface (at \(\theta ^3=\nicefrac {t}{2}\)). The seventh parameter\(\overset{(n)}{u}(\theta ^1,\theta ^2)\) is included in order to circumvent Poisson thickness locking [6]. Inserting (15) into the kinematic relations for the linearized strain tensor \(\pmb {\epsilon }= \epsilon _{ij} \; \mathbf {G}^{i} \otimes \mathbf {G}^{j}\) yields

with \(J_l^i = \mathbf {G}_{l} \cdot \mathbf {e}^{i}\). From the expression of \(\epsilon _{33}\) we see that the model can represent constant and linear normal strain states through the thickness.

3 Finite element method

In this section, we describe the developed finite element methods. The methods used for parametrically and implicitly defined shells differ from each other. However, in both cases, we employ the reference element technique for the construction of hierarchical \(H^1\)-conforming shape functions of arbitrary degree [32]. These element shape functions are pieced together to FEM basis functions by establishing a connection between local and global degrees of freedom. Furthermore, we use tensor-product (degenerated for triangles) Gauss–Legendre quadrature rules on the reference element for the integral evaluation. For shape functions of degree p, \((p+1)^2\) in-plane quadrature points are used on each element, whereas three quadrature points for the integration across the thickness are employed. In the following, \(\varPhi ^e\) denotes the local linear element mapping. The discretization of the seven parameters \(\left\{ \overset{(1)}{u_i}, \overset{(2)}{u_i}, \overset{(n)}{u} \right\} \in [H^1({\bar{U}})]^3\times [H^1({\bar{U}})]^3\times H^1({\bar{U}})\) introduced in (15) is done by means of

where \(\left\{ \overset{(1)}{u_{il}},\overset{(2)}{u_{il}},\overset{(n)}{u_{l}}\right\} \) are \(7 n_S\) unknown coefficients and \(N_l\) are the FEM basis functions.

3.1 FEM for shells defined by singular parametrizations

In this section, we describe the finite element method for the case where the parametrization \(\overline{\mathfrak {g}}\) of the reference surface is explicitly available. The geometry mappings for this method are depicted in Fig. 2. We use a quadrilateralization of the parametric plane \({\bar{U}}\). In (13), the derivatives of \(\overline{\mathfrak {g}}\) up to second order show up. In the present work we use an automatic differentiation schema based on an augmented algebra. To this end, a hyper-dual number class has been implemented providing operator overloading [19].

Special care has to be taken of singular parametrizations, where the determinant of the metric vanishes on some part of the geometry. In particular, we focus on the case where one side of the boundary is mapped to a single point in the real space. In this case, the stiffness matrix does not need to exist. We modify the ansatz space by combining and skipping basis functions. In the framework of Isogeometric Analysis, a similar strategy was considered in [33]. For presentational purposes, we assume that the boundary at the line \(\theta ^1 = 0\) in the parameter space is mapped to a single point \(P_0\) in the real space,

Obviously,

and the determinant of the metric is zero at the whole line \(\theta ^1 = 0\). We assume that apart from the line \(\theta ^1 = 0\) the parametrization is regular. Furthermore, it is assumed that \(\mathrm {G}_{11}>0\) and that the Laurent expansion of \(\mathrm {G}^{22} \sqrt{\left\langle \mathrm {G}_{\alpha \beta } \right\rangle }\) about \(\theta ^1 = 0\) is of the form

Investigation on the existence of

leads to the following modifications of the shape functions:

-

1.

All vertex-based shape functions related to the vertices on \(\theta ^1 = 0\) are added up to one single shape function.

-

2.

All edge-based shape functions related to the edges on \(\theta ^1 = 0\) are removed, i.e. the respective degrees of freedom are constrained to zero in the implementation.

-

3.

No modification of the cell-based shape functions is made.

The problematic term is

We remark that \(v_h\) are polynomials. The integral (22) exists if \(v_{h,2} = 0\) holds, i.e. \(v_h\) has to be constant with respect to \(\theta ^2\) or \(v_h = 0\) on \(\theta ^1 = 0\). Writing

the integral does not exist if any \(a_{0j} \ne 0\). The non-vanishing functions on \(\theta ^1 = 0\) are related to the nodes and edges there. All cell-based shape functions vanish on the boundary. A function \(v_h\) which is constant with respect to \(\theta ^2\) can be constructed summing up all node-based functions. This gives one new shape function. The edge-based shape functions are of higher order with respect to \(\theta ^2\) on \(\theta ^1 = 0\), they are thus eliminated.

3.2 FEM for implicitly defined shells

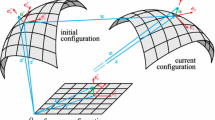

In the case of an implicitly defined reference surface, the parametrization \(\overline{\mathfrak {g}}\) over a flat parameter domain is not explicitly available. Therefore, the exact geometry is parametrized over a space triangulation \(\mathcal {T}_h\). To this end, we follow the strategy developed in [22]. The geometric concept is illustrated for the example of a sphere in Fig. 3. As a starting point we assume that a triangulation in space \(\mathcal {T}_h\) close to the exact surface is available. For each triangle \(\tau _e \in \mathcal {T}_h\) we have the standard affine mapping \(\varPhi _e\) which maps the reference triangle \(\tau _R\) to \(\tau _e\). We denote the piecewise flat surface defined by the triangulation by \({\bar{\varOmega }}_h\). In order to lift a point \(\mathbf{x}\in {\bar{\varOmega }}_h\) to the exact surface we introduce the mapping a in the following implicit way

Here, \(\mathbf s(\mathbf{x})\) are predefined search directions. The mapping a is implicitly defined because \(r(\mathbf{x})\) is not explicitly known and has to be computed in each evaluation of a such that \(\phi (a(\mathbf{x})) = 0\). We specify the search directions in (25) as follows. Let \(\mathcal {V}\) denote the set of all vertices of \(\mathcal {T}_h\). We set

where \(\nabla \phi \) is the usual gradient of the level-set function \(\phi \) in \(\mathbb {R}^3\). To preserve the exact geometry, we apply a modification at the vertices on the boundary of \(B\). Thus, we set

where \(\mathbf {n}_{\partial B}\) are the normal vectors to \(\partial B\). Then the search direction field \(\mathbf s({\mathbf x})\) defined on \({\bar{\varOmega }}_h\) is obtained by linear interpolation of \(\mathbf s_v({\mathbf x})\). Thus, the search direction field \(\mathbf s\) is given as a linear finite element function. We remark that the mapping (25) requires the solution of a non-linear root finding problem, which is numerically realized with the Newton–Raphson method. We obtain an element-wise parametrization \(\mathfrak {g}^e\) of \({\bar{\varOmega }}\) over the reference element \(\tau ^R\) by

The evaluation of the integrals in (13) requires \(\mathbf{x}= \mathfrak {g}^e(\theta ^1,\theta ^2)\), the base vectors \(\mathbf {\overline{G}}_{\alpha }\) and the coefficients of the second fundamental form \(h_{\alpha \beta }\). All other geometric quantities can be computed from them by algebraic operations. The formula

for the computation of the base vectors can be found in [22]. Taking into account the dependencies

the chain rule results in

Together with (5) the coefficients of the second fundamental form can be computed by

For the gradient of the normal vector we have

Thus, we have to provide the second order derivatives of the level-set function \(\phi \) in the implementation.

In order to clarify the explanations on the implicit method, we remark that the space triangulation represents an intermediate step in the method and does not define the geometry. The key ingredient of the implicit method is the mapping a defined in (25), which maps the space triangulation to the exact geometry. However, this mapping is only implicitly defined and a one dimensional root finding problem has to be solved for the evaluation. This is no problem because the integrals are approximated by quadrature. Thus, only a point-wise evaluation is necessary.

4 Numerical results

In this section, we demonstrate the correct implementation of the developed methods and their capabilities. The verification examples are based on the method of manufactured solutions in order to have exact solutions to compare with. As an error measure we use

where \(\left\{ \overset{(1)}{u_{i}},\overset{(2)}{u_{i}},\overset{(n)}{u}\right\} _M\) is the exact manufactured solution and \(\left\{ \overset{(1)}{u_{i}},\overset{(2)}{u_{i}},\overset{(n)}{u}\right\} _h\) the numerical solution. In (34), the sum has to be understood over the seven shell model parameters.

4.1 Verification example for a parametrically defined shell

In order to verify the implementation, we employ the method of manufactured solutions, which has been demonstrated in [21] for parametrically defined surfaces. In this example, we use the reference surface defined by the parametrization

and \((\theta ^1,\theta ^2) \in [0,0.56]\times [0,0.65]\), see Fig. 4. The shell has the thickness \(t=0.01\). The Young’s modulus is \(E = 8\cdot 10^4\), whereas Poisson’s ration is \(\nu = 0.25\). We study the convergence of the method under uniform mesh refinement. We remark that we have checked the convergence for different displacement fields. Here, we present the results for the prescribed solution \(\overset{(1)}{u_{1}} = \cos (20\,\theta ^1)\), \(\overset{(1)}{u_{2}} = 0\), \(\overset{(1)}{u_{3}} = \sin (10\,\theta ^2)\), \(\overset{(2)}{u_{1}} = \sin (10\,\theta ^1\,\theta ^2)\), \(\overset{(2)}{u_{2}} = 0\), \(\overset{(2)}{u_{3}} = 0\), and \(\overset{(n)}{u} = \sin (10\,\theta ^1\,\theta ^2)\). A regular mesh obtained by uniform subdivision of the parameter space into \(2\times 2 = 4\) elements represents refinement level 0. We get the subsequent refinement levels by uniform subdivision of the previous level. The results of the convergence study are depicted in Fig. 5. We observe optimal convergence rates, i.e. \(\mathcal {O}(h^{p+1} )\)-convergence, where h is a characteristic element length.

4.2 Verification example for an implicitly defined shell

The implementation of the FEM for an implicitly defined shell is verified. To this end, we consider a manufactured solution on a torus. The geometry of the considered surface is defined by the zero level-set of the function

and \(B=[-1.5,0.3]\times [-0.5,0.5]\times [0,1.1]\). The problem geometry is illustrated in Fig. 6. As an important feature, we remark that d is the signed distance function of the torus. In order to come up with a manufactured solution, we construct a displacement field with respect to Cartesian coordinates. This displacement field should fulfill the kinematic assumptions introduced in (15). We note that the closest point projection

is explicitly available, which maps \({\tilde{\mathbf{x}}} \in \mathbb {R}^3\) to a point \(\mathbf{x}\in {\bar{\varOmega }}\) on the reference surface. Thus, a point \({\tilde{\mathbf{x}}}\) has the decomposition \((\mathbf{x},d)\). This allows us to adapt (15) to

since \(\mathbf {n}= \nabla d\). With the displacement field given in (38), the source terms follow easily from the relations in (12). We remark that we have checked the convergence for different displacement fields. Here, we present the results for the prescribed solution

Again, we study the convergence rates under uniform mesh refinement. We remark that, because of the mapping of \({\bar{\varOmega }}_h\) to \({\bar{\varOmega }}\) used in the method, it is sufficient to subdivide the triangles of \(\mathcal {T}_h\) in a refinement step. Thus, for all refinement levels \({\bar{\varOmega }}_h\) is the one and the same surface. The results of the convergence study are given in Fig. 7. We observe optimal convergence rates.

4.3 Pinched hemisphere

In this example, we consider the pinched hemisphere problem in order to test the suggestion how to handle a singular parametrization. This example is taken from the popular shell obstacle course [4]. The reference surface is described by

and \((\theta ^1,\theta ^2) \in [0,2\pi ] \times \left[ 0,\nicefrac {\pi }{2}\right] \). This parametrization fulfills the assumptions in Sect. 3.1. The material properties and the general problem setup are shown in Fig. 8. The edge of the hemisphere is unconstrained and the four radial forces have alternating signs such that the sum of the applied forces is zero. We investigate the radial displacement at the loaded points. In [4], the reference displacement of \(u_r = 0.0924\) is given. Our results are given in Table 1.

Obviously, the low order methods underestimate the displacement significantly for the considered meshes. This is expected as the low order elements (linear, quadratic, cubic) can only poorly represent rigid body rotations and are affected by locking. However, the high order methods (quartic and higher) converge quickly. We further investigate the ability to represent rigid body motions by inspection of the eigenvalues of the stiffness matrix. The three rigid body translations can be represented exactly by the elements, resulting in three zero (up to numerical round-off errors) eigenvalues. As the rigid body rotations are only approximated the next three eigenvalues are nonzero. The sixth smallest eigenvalues for different meshes and polynomial orders are given in Table 2. As expected they decrease rapidly with increasing polynomial order.

Furthermore, we have solved the pinched hemisphere with the implicit formulation. The triangulations shown in Fig. 9 have been used. As an input we have given the four element triangulation where all vertices are on the reference surface. All other meshes have been obtained by uniform refinement. In contrast to a classical method, there is no need to better approximate the geometry by these triangulations, since they are mapped to the exact geometry within the method. In Table 3 the computed radial displacements at the loaded points are given. These results are similar to the results obtained by the parametric method given in Table 1.

4.4 Scordelis-Lo roof

We consider the Scordelis-Lo roof problem, which is also an example from the shell obstacle course [4]. It is a popular benchmark test to assess the performance of finite elements regarding complex membrane strain states. The cylindrical roof (radius \(r={25}\)) is supported by rigid diaphragms at the ends (\(x={0}\) and \(x={50}\)), i.e. \(u_y=u_z={0}\). All other surfaces are free. The geometry and the material parameters are depicted in Fig. 10. The structure is subjected to gravity loading with \({\mathbf b}=-\mathbf {e}_{z} \, {360}\). For the parametrization of the reference surface, we use

with the function

We use the function \(\kappa \) in order to capture the boundary layer. It has the properties \(\kappa (0)=0\), \(\kappa (1)=1\), \(\kappa '(0) = \kappa '(1) = b\) and is illustrated in Fig. 11. The parameter space is given by \(\theta ^1\in [0,1]\) and \(\theta ^2\in [0,1]\). In Fig. 10, a \(16\times 16 = 256\) element mesh mapped to the real space is illustrated.

We study the vertical displacement of point A, which is located in the middle of one free edge and on the mid-surface. We remark that the vertical displacement varies considerably trough-the-thickness. The results for different ansatz orders and meshes are given in Table 4. It is evident that the low order methods are affected by locking. The results obtained with linear ansatz functions are far from the converged solution \(u_z={-0.3014}\). Raising the ansatz order reduces the locking phenomena. Without resorting to other techniques to reduce the locking, we advise to use at least quartic ansatz functions. In [27], a reference value \(u_z={-0.3024}\) for the vertical displacement at point A is reported. For a shell model based on equivalent seven-parameter kinematics, \(u_z={-0.3008}\) is computed in [18]. Therefore, our results are in accordance with the values found in literature.

4.5 Gyroid

In this example, we consider the deformation of a shell structure where the reference surface is part of a gyroid, see Fig. 12. An approximation of a gyroid is given by the level-set function

The considered shell lies in \(B= [{0},{2}]\times \)\([{-0.5},{0.5}]\times \)\([{-0.5},{0.5}]\). The shell structure is fixed at the plane \(x={0}\). We assume a thickness \(t= {0.03}\).

We study the static deformation due to a volume load \({\mathbf b}=\mathbf {e}_{z} \, {10^7}\). To this end, we use three different surface meshes, which are depicted in Fig. 13. The coarsest mesh is obtained by the Marching Cubes Algorithm [26] and mesh smoothing. The other two meshes are obtained by uniform refinement of the coarsest mesh. We remark that, in the analysis, each mesh is mapped to the exact surface by means of (28). Table 5 illustrates the convergence of the vertical displacement \(u_z\) at the point \([ 2, {0.5}, {-0.25}]\). Obviously, the results obtained by linear ansatz functions underestimate the deformation tremendously for the considered meshes. The use of quadratic ansatz functions reduces the locking considerably. In view of the results obtained by the octic ansatz functions, we can accept a converged value of \(u_z = {1.8812}\).

5 Conclusion

In this paper, high order finite element methods for shell analysis have been presented. The underlying shell model is a displacement based seven-parameter model. As a special feature, the methods incorporate the exact geometry of parametrically and implicitly defined reference surfaces. We have shown the capabilities of the methods in five examples. In order to assess the convergence behavior, the method of manufactured solutions has been utilized. In all numerical experiments, we observe optimal convergence rates in the asymptotic range.

In the present work we used a purely displacement based formulation. Thus, various locking phenomena reduce the efficiency of the method when using low order approximations. In order to reduce locking phenomena, we have resorted to high order shape functions (our implementation allows for arbitrary high order). As this might be not very efficient in many examples, it would be interesting to develop low order locking-free elements based on the exact geometry in future work.

Moreover, the use of a seven-parameter shell model allowed us to use \(H^1\)-conforming ansatz and test spaces. This might not be appropriate for other shell models like Kirchhoff–Love type models or Reissner–Mindlin type models. In the former, typically, \(H^2\)-conforming elements are needed, whereas in the latter elements are necessary providing a vector field tangential to the surface. The development of such elements for implicitly defined shells should receive further attention.

References

Arciniega R, Reddy J (2007) Tensor-based finite element formulation for geometrically nonlinear analysis of shell structures. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 196(4):1048–1073

Babuška I, Pitkäranta J (1990) The plate paradox for hard and soft simple support. SIAM J Math Anal 21(3):551–576

Basar Y, Krätzig WB (1985) Mechanik der Flächentragwerke: Theorie, Berechnungsmethoden, Anwendungsbeispiele. Vieweg

Belytschko T, Stolarski H, Liu WK, Carpenter N, Ong JS (1985) Stress projection for membrane and shear locking in shell finite elements. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 51(1):221–258

Benson D, Bazilevs Y, Hsu MC, Hughes T (2010) Isogeometric shell analysis: the Reissner–Mindlin shell. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 199(5):276–289

Bischoff M, Ramm E (1997) Shear deformable shell elements for large strains and rotations. Int J Numer Methods Eng 40(23):4427–4449

Bischoff M, Ramm E (2000) On the physical significance of higher order kinematic and static variables in a three-dimensional shell formulation. Int J Solids Struct 37(46–47):6933–6960

Bischoff M, Bletzinger KU, Wall W, Ramm E (2004) Models and finite elements for thin-walled structures. In: Stein E, de Borst R, Hughes T (eds) Encyclopedia of computational mechanics, chap 3, vol 2. Wiley Online Library, New York, pp 59–137

Chapelle D, Bathe KJ (2010) The finite element analysis of shells. Springer, Berlin

Cho M, Roh HY (2003) Development of geometrically exact new shell elements based on general curvilinear co-ordinates. Int J Numer Methods Eng 56(1):81–115

Ciarlet PG (2006) An introduction to differential geometry with applications to elasticity, vol 78. Springer, Berlin

Ciarlet PG, Lods V (1996) Asymptotic analysis of linearly elastic shells. I. Justification of membrane shell equations. Arch Ration Mech Anal 136(2):119–161

Ciarlet PG, Lods V (1996) Asymptotic analysis of linearly elastic shells. III. Justification of Koiter’s shell equations. Arch Ration Mech Anal 136(2):191–200

Ciarlet PG, Lods V, Miara B (1996) Asymptotic analysis of linearly elastic shells. II. Justification of flexural shell equations. Arch Ration Mech Anal 136(2):163–190

Dauge M, Faou E, Yosibash Z (2004) Plates and shells: asymptotic expansions and hierarchic models. In: Stein E, de Borst R, Hughes T (eds) Encyclopedia of computational mechanics, chap 8, vol 2. Wiley Online Library, New York, pp 199–236

Demlow A (2009) Higher-order finite element methods and pointwise error estimates for elliptic problems on surfaces. SIAM J Numer Anal 47(2):805–827

Dziuk G, Elliott C (2013) Finite element methods for surface PDEs. Acta Numer 22:289–396

Echter R, Oesterle B, Bischoff M (2013) A hierarchic family of isogeometric shell finite elements. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 254:170–180

Fike JA, Alonso JJ (2011) The development of hyper-dual numbers for exact second-derivative calculations. In: 49th AIAA aerospace sciences meeting including the new horizons forum and aerospace exposition, Orlando, Florida

Fries TP, Schöllhammer D (2017) Higher-order meshing of implicit geometries part II: approximations on manifolds. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 326:270–297

Gfrerer MH, Schanz M (2017) Code verification examples based on the method of manufactured solutions for Kirchhoff–Love and Reissner–Mindlin shell analysis. Eng Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-017-0572-4

Gfrerer MH, Schanz M (2018) A high-order FEM with exact geometry description for the Laplacian on implicitly defined surfaces. Int J Numer Methods Eng. https://doi.org/10.1002/nme.5779

Hosseini S, Remmers JJ, Verhoosel CV, Borst R (2013) An isogeometric solid-like shell element for nonlinear analysis. Int J Numer Methods Eng 95(3):238–256

Kiendl J, Bletzinger KU, Linhard J, Wüchner R (2009) Isogeometric shell analysis with Kirchhoff–Love elements. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 198(49):3902–3914

Lehrenfeld C (2016) High order unfitted finite element methods on level set domains using isoparametric mappings. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 300:716–733

Lorensen W, Cline H (1987) Marching cubes: a high resolution 3D surface construction algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 14th annual conference on computer graphics and interactive techniques, ACM, New York, NY, USA, SIGGRAPH’87, pp 163–169

Macneal RH, Harder RL (1985) A proposed standard set of problems to test finite element accuracy. Finite Elem Anal Des 1(1):3–20

Oesterle B, Sachse R, Ramm E, Bischoff M (2017) Hierarchic isogeometric large rotation shell elements including linearized transverse shear parametrization. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 321:383–405

Pimenta PM, Campello EMB (2009) Shell curvature as an initial deformation: a geometrically exact finite element approach. Int J Numer Methods Eng 78(9):1094–1112

Ramm E, Wall W (2004) Shell structures—a sensitive interrelation between physics and numerics. Int J Numer Methods Eng 60(1):381–427

Rank E, Düster A, Nübel V, Preusch K, Bruhns O (2005) High order finite elements for shells. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 194(21):2494–2512

Schöberl J, Zaglmayr S (2005) High order Nédélec elements with local complete sequence properties. Compel 24(2):374–384

Takacs T, Jüttler B (2011) Existence of stiffness matrix integrals for singularly parameterized domains in isogeometric analysis. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 200(49):3568–3582

Weingarten J (1861) Ueber eine Klasse auf einander abwickelbarer Flächen. J Reine Angew Math 59:382–393

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Graz University of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gfrerer, M.H., Schanz, M. High order exact geometry finite elements for seven-parameter shells with parametric and implicit reference surfaces. Comput Mech 64, 133–145 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-018-1661-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-018-1661-y