Abstract

Background

Robotic surgery has gained popularity for the reconstruction of pelvic floor defects. Nonetheless, there is no evidence that robot-assisted reconstructive surgery is either appropriate or superior to standard laparoscopy for the performance of pelvic floor reconstructive procedures or that it is sustainable. The aim of this project was to address the proper role of robotic pelvic floor reconstructive procedures using expert opinion.

Methods

We set up an international, multidisciplinary group of 26 experts to participate in a Delphi process on robotics as applied to pelvic floor reconstructive surgery. The group comprised urogynecologists, urologists, and colorectal surgeons with long-term experience in the performance of pelvic floor reconstructive procedures and with the use of the robot, who were identified primarily based on peer-reviewed publications. Two rounds of the Delphi process were conducted. The first included 63 statements pertaining to surgeons’ characteristics, general questions, indications, surgical technique, and future-oriented questions. A second round including 20 statements was used to reassess those statements where borderline agreement was obtained during the first round. The final step consisted of a face-to-face meeting with all participants to present and discuss the results of the analysis.

Results

The 26 experts agreed that robotics is a suitable indication for pelvic floor reconstructive surgery because of the significant technical advantages that it confers relative to standard laparoscopy. Experts considered these advantages particularly important for the execution of complex reconstructive procedures, although the benefits can be found also during less challenging cases. The experts considered the robot safe and effective for pelvic floor reconstruction and generally thought that the additional costs are offset by the increased surgical efficacy.

Conclusion

Robotics is a suitable choice for pelvic reconstruction, but this Delphi initiative calls for more research to objectively assess the specific settings where robotic surgery would provide the most benefit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Pelvic floor reconstructive surgery (PFRS) is an emerging field of application for robotic platforms, with expert users experiencing advantages from the improved vision and dexterity, which they assert are particularly useful during abdominal procedures for prolapse. Clarity of vision in narrow anatomical areas and facilitated dissection and stitching in the deep pelvis are often indicated as key reasons why surgeons choose a robotic approach to perform abdominal pelvic organ prolapse (POP) reconstructive procedures. Robotic assistance has been used for all the described abdominal techniques, including sacral suspension, lateral suspension, rectal suspension, and para-vaginal repair, as well as anti-incontinence procedures [1,2,3,4,5,6].

Evidence corroborating the perception that robotics makes PFRS easier or more effective is so far missing, including safety, reproducibility, and efficacy in the hands of surgeons with different levels of experience. Nonetheless, studies have suggested that robotic surgery reduces the conversion rate to laparotomy and shortens the learning curve for complex procedures, such as colposacropexy [7,8,9]. Expert users of the robot believe that this platform may facilitate the development and spread of PFRS procedures, with better functional outcomes and long-term success rates for the treatment of advanced or multicompartmental prolapses compared with traditional transvaginal or transperineal procedures [4, 10].

Improving the efficacy of PFRS would have a relevant impact because this surgery is performed in high numbers and repeat procedures due to relapses increase expenditures [11]. In this light, sustainability and cost-effectiveness of using the robot for POP surgery should be thoroughly assessed [12, 13]. These answers will apply to urologic, gynecologic, and proctologic procedures because of the similarities in terms of anatomical dissection, suspensive strategies, and technical challenges [6].

The current study uses a Delphi methodology to report the experience of expert users on the performance of the Da Vinci® robotic platform (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA) for PFRS. Our results represent the opinions of an international group of high-volume surgeons from various specialties on the role of robot-assisted PFRS.

Materials and methods

The study is based on the Delphi process, a method of structured communication applied to reach a consensus on a specific topic with input from a panel of experts. The Delphi technique uses a multistage, self-completed questionnaire with individual feedback [14, 15].

Selection of the participants

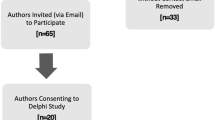

Between November 2020 and September 2021, 37 high-volume robotic surgeons with extensive experience in pelvic floor reconstruction from all over the World were invited to join this project. Urogynecologists, urologists, and colorectal surgeons with an interest in proctology were included. Candidates were identified primarily based on peer-reviewed publications on robotic PFRS procedures or because of involvement in robotic special interest groups from international scientific societies dedicated to pelvic floor disorders. Participant selection was performed by the organizers of the initiative (Tommaso Simoncini and Gabriele Naldini, with the aid of collaborators).

Upon invitation of the 37 candidates, 4 declined participation or did not answer and 7 accepted but did not complete either the first or the second round of questions and were therefore excluded. Nonresponders were evenly distributed in the different geographic areas and surgical specialties. Twenty-six experts completed all Delphi rounds and participated in the joint discussion during the final teleconference, where the results were presented. The number of participants is within the range that is considered appropriate for Delphi studies [15].

A scientific committee was formed at the beginning of the process and included the 2 organizers plus 5 surgeons who were representative of the various specialties, geographic distributions, and both sexes (Consten, Davila, Meurette, Reisenauer, and Schraffordt Koops). The professional characteristics of the experts involved in the Delphi process are described in Table 1.

The Delphi process

The Delphi process was initiated by identifying the research statements. This was done by the scientific committee through a series of teleconferences. A total of 64 questions and statements were formulated for the first round, divided into 5 categories: 8 questions related to surgeons’ characteristics and 56 general statements, indications, surgical technique, and future-oriented statements. The questionnaire was sent to the participants using Google modules. The participants were asked to vote using a binary Likert scale of 1 through 9 to express their degree of agreement with the statement (with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 9 strong agreement). The participants were also asked to provide a comment explaining their choice.

Upon completion of the first round, the scientific committee analyzed the responses. As predefined in the study setup, those statements for which 70% or more of the group declared disagreement (score of 1–3) or agreement (score of 7–9) were excluded from the second round. Similarly, statements for which the group showed no concordance (scatter distribution of scores) were considered areas of no consensus and were excluded. Those statements for which 60% to 70% of the group either agreed or disagreed were reanalyzed by the scientific committee by looking at the explanatory comments. The committee rephrased these statements for the second round.

The second questionnaire was composed of 20 statements, and the same procedure was followed for analysis. The Delphi statements and the level of agreement of round 1 and round 2 are listed in Table 2 and Table 3.

The scientific committee then adjudicated the areas of consensus and of lack of agreement and performed subanalyses looking at how the opinions of the group varied based on the specialty of the surgeons, the surgeons’ experience with the use of the robot, surgeons’ annual case load, and on their habit of using also standard laparoscopy.

The third and concluding step of the Delphi process consisted of a face-to-face virtual meeting with all the participants, where the data were reviewed, and several comments were discussed and agreement with the analysis of the committee was verified.

Data analysis

Categorical data are described as absolute frequency. Stratified analyses of responses to questions of the 2 Delphi rounds, as a dichotomized agreement, were performed with chi-square test (χ2), Fisher’s exact test, and χ2 test for trend. Significance was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed with SPSS technology v.27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

The first questions in the first Delphi round provided a description of the participants (Table 1). Participants were representative of the 3 specialties and of different geographic areas and health systems. Most of the participants had been using the robot to perform PFRS for more than 3 years, with a mean of more than 20 procedures per year. Half of the group performed PFRS via both laparoscopic and robotic techniques and a majority also performed transvaginal surgery, with nearly 40% of the group performing transanal procedures. Most of the participants (88%) worked in a multidisciplinary pelvic floor center.

General aspects of the role of robotic assistance for PFRS

The first set of practice questions explored general aspects of the use of robotics for PFRS. The experts strongly agreed that the use of the robot to perform PFRS is safe. In general, the group believed that the robotic platform allows better vision during PFRS and that the range of motion and articulation of the robotic instruments provides a specific advantage during this surgery.

The experts agreed that performing PFRS with the robot causes less physical strain and less fatigue for the surgeon compared with conventional laparoscopic surgery. They also thought that the Da Vinci Xi platform reduces operative time versus standard laparoscopy for reconstructing the pelvic floor in complex cases. Nonetheless, they did not feel that using the robot allows the performance of a higher number of procedures within the same day (compared with standard laparoscopy).

The experts also agreed that the learning curve of PFRS procedures is shorter for robotic surgery than for laparoscopy and that it is easier to transfer surgical competencies to other surgeons using the robot. To this extent, the experts subscribed to the idea that having a dedicated center for robotic surgery with expert staff would facilitate use of the robot for non-oncologic applications such as PFRS and that training sessions for inexperienced surgeon assistants are important to reach proficiency.

The experts generally agreed that the robot facilitates quicker discharge of patients. In addition, there was a generalized opinion that collecting patient-reported outcome measures and/or patient-reported experience measures will be a useful tool to show the multidimensional (e.g., socioeconomic) benefits of this technology.

Overall, the experts strongly concurred that they would recommend the use of robot-assisted surgery for PFRS to other colleagues.

Indications of robotics for PFRS

The second set of practice questions tested the opinions of the experts on the correct indications for the use of the robotic platform for PFRS procedures.

The panel agreed that robotic surgery is preferable to standard laparoscopy for obese patients and for patients with previous abdominal surgeries. Cases of advanced or multicompartmental prolapse, relapsed/recurrent prolapse, or previous reconstructive surgery with meshes were also considered indications for preferring use of the robot over standard laparoscopy. Although the experts concurred that the use of robotics is preferable in more complex cases, they did not believe that robotics should be limited to selected indications.

Surgical technique in robot-assisted PFRS

The third set of practice items addressed the technicalities of using the robot to perform PFRS.

The experts agreed that the robotic platform provides specific technical advantages over standard laparoscopy for performing all the key steps of abdominal PFRS. Specifically, experts perceived an advantage for dissection of the sacral promontory, the vesicovaginal space, the rectovaginal space, and the Retzius space. In contrast, the experts did not feel that the use of robotics decreases the risk of nerve injury at the level of the promontory compared with standard laparoscopy.

Experts considered suturing in all the districts that are relevant for PFRS procedures to be significantly easier using the robot, including the anterior and posterior vaginal wall, the Retzius space, and the sacral promontory. Suturing on the anterior rectal wall was considered both easier and safer with the robotic technique compared with laparoscopy. Further, mesh placement was thought to be more precise with the use of robotic instruments compared with standard laparoscopy.

Related to safety, the experts did not feel that major vascular damage at the level of the sacral promontory would be any more difficult to manage with robotics than with standard laparoscopy.

On a more technical note, the group agreed that use of the fourth robotic arm is not necessary to perform PFRS in simple cases and that standard robotic monopolar and bipolar instruments are sufficient. The experts expressed interest in the development of a single-port robotic platform for PFRS.

Future perspectives on robot-assisted PFRS

When the experts were asked about the future role of robotics in the management of pelvic floor defects, they agreed that they would recommend activation of a robotic program for the management of these disorders. The group also deemed it important from the patient’s perspective that a hospital managing pelvic floor diseases is equipped with a robotic platform.

From a health economics point of view, considering both the costs and benefits, the experts agreed that robotic surgery should be considered a suitable technology for patients requiring abdominal correction of POP. The experts also thought that the expanding use of the robot for PFRS may offer socioeconomic advantages (e.g., increased performance of transabdominal reconstructive procedures or possible decreases in relapses).

When asked to select possible refinements of the robotic platform that could improve the performance of PFRS, most experts indicated the development of tactile feedback, artificial intelligence or deep learning dedicated to PFRS, and tools for preoperative anatomical planning and surgical navigation.

Subanalyses

The results were reanalyzed to explore whether surgeons of different specialties, experience, caseloads, and patterns of surgical practice may differ in opinion on selected questions. Items for which statistically significant differences were found are reported.

Gynecologists strongly believed that pelvic floor reconstruction is a suitable indication for robotics only for selected patients, whereas colorectal surgeons and urologists did not (Table 4).

When the opinions of surgeons were analyzed by years of experience (< 5 vs ≥ 5 years), only the more-experienced surgeons agreed that after a day of robotic surgery they felt less tired than after a day of conventional surgery (Table 4).

The opinions of experts were also compared by case-load of robotic PFRS procedures (< 20, 20–40, or > 40 per year) (Table 4). Surgeons performing fewer than 20 robotic cases per year did not feel that the robot facilitates managing major vascular damage at the level of the sacral promontory. Surgeons with a high case-load had an opposite opinion. Surgeons performing more than 40 procedures per year disagreed with the view that it is not necessary to have expertise in traditional laparoscopy to perform robotic pelvic floor surgery. Only the surgeons with the higher case-load agreed that they felt less tired after a day of robot-assisted PFRS than after conventional surgery.

While all the experts were skilled laparoscopic surgeons with experience in laparoscopic PFRS, a subgroup reported currently using only the robot to perform these procedures. We then ran a subanalysis comparing the opinions of surgeons who perform PFRS only with the robot compared with surgeons who perform both robotics and conventional laparoscopic procedures (Table 5). Experts performing only robotic surgery felt that the robot offers several advantages over laparoscopy: decreased rates of complications, more precise and safer isolation of the sacral promontory, easier deep dissection between the rectum and the vagina, better positioning of meshes, easier suturing of meshes on the anterior rectal wall, lower risk of injuries to the pelvic ureters, and easier performance of hysterectomy in the context of PFRS. Experts performing both robotic and laparoscopic surgeries did not agree on the previous points. Only surgeons who exclusively use the robot felt that PFRS is a suitable indication for robotics for every patient.

Discussion

Robots are expensive tools that facilitate the performance of surgical maneuvers through better vision and more effective instruments. These technologically advanced platforms ease the execution of minimally invasive procedures by less-experienced surgeons or make the performance of a technically challenging procedure more effective in the hands of an expert laparoscopic surgeon, thus extending the indications of minimally invasive surgery beyond the boundaries set by the limitations of standard laparoscopic instruments [3].

Whether a robotic approach is of significant advantage for a specific procedure depends on the procedure itself, the patient’s characteristics, and the surgeon’s skills; hence it is difficult to measure objectively. If one adds the economic impact of the use of a robot, some procedures, including PFRS, are more debatable as indications because they are associated with lower reimbursements [12, 13].

Nonetheless, the advantage of a surgical tool should be measured based on the degree of technical advantage that it confers during a specific procedure rather than on its cost [16]. The selection of procedures that benefit most from the added cost of such instruments is considered good clinical practice.

Applying the same metric to the complexity of robotic platforms is not easy because multiple parameters influence decision-making. For instance, patients may be attracted toward robotic centers because they consider them more modern [17, 18], which may lead to an economic advantage for the organizations that are equipped with these instruments.

One of the ways to assess the value of robotics in a specific surgical setting is to assess the opinions of expert users who can express through personal experience the technical and nontechnical strengths and weaknesses in comparison with other approaches. We followed this approach to explore the value of robotics in PFRS with the use of a Delphi methodology. This approach has recently become popular to assess robotic surgery [19, 20], including training [21], and the role of innovations related to this surgical approach [22].

Our study confirms that surgeons who use the robot extensively consider this approach safe and generally more effective than standard laparoscopy for PFRS. The experts involved in the Delphi process agreed that the technical advantages of the Da Vinci® robotic platform are evident in all the surgical steps required to perform urogynecology and colorectal PFRS procedures. Specifically, dissection of relevant anatomical planes, mesh placement, suture placement, and knot tying are easier and more effective using the robot than with standard laparoscopy. The participating experts believe that these features allow easier and more effective learning of complex prolapse procedures, particularly in the presence of a robotic center, consistent with previous observations [23,24,25]. The experts generally agreed that robotics is particularly useful for the treatment of more complex prolapse cases.

Enhanced efficacy and safety were also perceived by the experts; hence they considered the robotic platform as a means to facilitate early discharge of patients. Consistent with this view, recent research has investigated the possibility of enhanced recovery after surgery protocols combined with early, same day, and even ambulatory surgery for PFRS procedures performed with the robot [26,27,28,29,30].

Some interesting differences were identified in the group subanalyses. Gynecologists felt that robotic POP surgery should be limited to selected and more complex cases, whereas urologists and colorectal surgeons did not. This difference could be due to the different case mixes of procedures and selection algorithms for robotics in the 3 specialties; however, since urologists were less numerous in the expert groups, this finding might be biased.

A number of experts over time had chosen to perform PFRS only with the robot. This group showed a stronger appreciation for the technical advantages of this platform compared to those who used both robotics and standard laparoscopy. They indeed believed that robotics should not be limited to selected cases but that it is instead useful also for less complex procedures. This finding shows how within an expert group of pelvic floor surgeons, a significant proportion elected using only the robot to perform PFRS due to perceived technical advantages. We did not explore whether those using both laparoscopy and robotics did so for a strategic surgical choice or because of other factors (e.g., limited access to the robotic platform).

Another interesting difference was that the more-experienced surgeons were more likely to emphasize the ergonomic advantages of the robotic platform and were convinced that it decreased the duration of PFRS procedures, possibly indicating that continued use leads to better exploitation of the benefits of the robot. This may suggest that centralization of robotic procedures in the hands of high-volume surgeons could have advantages.

Overall, the general feeling of the group of gynecologists, urologists, and colorectal surgeons’ expert in the use of the robotic platform for PFRS was that robotics is appropriate for this type of surgery given the significant technical advantages and the overall cost–benefit balance. This Delphi initiative calls for more research to objectively assess the specific settings where robotic surgery might be more wisely chosen over standard laparoscopy, with the overarching objective of improving patient care and sustainability.

Study limitations

This study has some limitations. The study population is a self-selected group of expert pelvic floor surgeons who may have more positive feelings and confidence with robot-assisted surgery than those who did not participate. Also, while the sample size of the total group is within the recommended range for a Delphi analysis, groups in the subanalyses are smaller, which is an obvious limitation.

References

Pushkar DY, Kasyan GR, Popov AA (2021) Robotic sacrocolpopexy in pelvic organ prolapse: a review of current literature. Curr Opin Urol 31:531–536. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOU.0000000000000932

Pan K, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang Y, Xu H (2016) A systematic review and meta-analysis of conventional laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy versus robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Int J Gynecol Obstet 132:284–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.08.008

Schachar JS, Matthews CA (2020) Robotic-assisted repair of pelvic organ prolapse: a scoping review of the literature. Transl Androl Urol 9:959–970. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2019.10.02

Flynn J, Larach JT, Kong JCH, Warrier SK, Heriot A (2021) Robotic versus laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 36:1621–1631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-021-03904-y

Albayati S, Chen P, Morgan MJ, Toh JWT (2019) Robotic vs. laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy for external rectal prolapse and rectal intussusception: a systematic review. Tech Coloproctol 23:529–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-019-02014-w

Naldini G, Fabiani B, Sturiale A, Russo E, Simoncini T (2021) Advantages of robotic surgery in the treatment of complex pelvic organs prolapse. Updates Surg 73:1115–1124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00913-4

Capmas P, Suarthana E, Larouche M (2021) Conversion rate of laparoscopic or robotic to open sacrocolpopexy: are there associated factors and complications? Int Urogynecol J 32:2249–2256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04570-4

Callewaert G, Bosteels J, Housmans S, Verguts J, van Cleynenbreugel B, van der Aa F, de Ridder D, Vergote I, Deprest J (2016) Laparoscopic versus robotic-assisted sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review. Gynecol Surg 13:115–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-016-0930-z

Mäkelä-Kaikkonen J, Rautio T, Klintrup K, Takala H, Vierimaa M, Ohtonen P, Mäkelä J (2014) Robotic-assisted and laparoscopic ventral rectopexy in the treatment of rectal prolapse: a matched-pairs study of operative details and complications. Tech Coloproctol 18:151–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-013-1042-7

Giannini A, Caretto M, Russo E, Mannella P, Simoncini T (2019) Advances in surgical strategies for prolapse. Climacteric. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2018.1543266

Giannini A, Russo E, Cano A, Chedraui P, Goulis DG, Lambrinoudaki I, Lopes P, Mishra G, Mueck A, Rees M, Senturk LM, Stevenson JC, Stute P, Tuomikoski P, Simoncini T (2018) Current management of pelvic organ prolapse in aging women: EMAS clinical guide. Maturitas. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.02.004

Mäkelä-Kaikkonen J, Rautio T, Ohinmaa A, Koivurova S, Ohtonen P, Sintonen H, Mäkelä J (2019) Cost-analysis and quality of life after laparoscopic and robotic ventral mesh rectopexy for posterior compartment prolapse: a randomized trial. Tech Coloproctol 23:461–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-019-01991-2

Wang R, Hacker MR, Richardson M (2021) Cost-effectiveness of surgical treatment pathways for prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 27:E408–E413. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000948

Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Wood TJ, Gonsalves C, Ufholz LA, Mascioli K, Wang C, Foth T (2017) The use of the Delphi and other consensus group methods in medical education research: a review. Acad Med 92:1491–1498. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001812

Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C (2011) Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020476

Lyons SD, Law KSK (2013) Laparoscopic vessel sealing technologies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 20:301–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2013.02.012

Chu CM, Agrawal A, Mazloomdoost D, Barenberg B, Dune TJ, Pilkinton ML, Chan RC, Weber Lebrun EE, Arya LA (2019) Patients’ knowledge of and attitude toward robotic surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 25:279–283. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000556

Thomas D, Medoff B, Anger J, Chughtai B (2020) Direct-to-consumer advertising for robotic surgery. J Robot Surg 14:17–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-019-00989-0

Müller PC, Kapp JR, Vetter D, Bonavina L, Brown W, Castro S, Cheong E, Darling GE, Egberts J, Ferri L, Gisbertz SS, Gockel I, Grimminger PP, Hofstetter WL, Hölscher AH, Low DE, Luyer M, Markar SR, Mönig SP, Moorthy K, Morse CR, Müller-Stich BP, Nafteux P, Nieponice A, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, Nilsson M, Palanivelu C, Pattyn P, Pera M, Räsänen J, Ribeiro U, Rosman C, Schröder W, Sgromo B, van Berge Henegouwen MI, van Hillegersberg R, van Veer H, van Workum F, Watson DI, Wijnhoven BPL, Gutschow CA (2021) Fit-for-discharge criteria after esophagectomy: an international expert Delphi consensus. Dis Esophagus. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doaa101

Fuchs HF, Collins JW, Babic B, DuCoin C, Meireles OR, Grimminger PP, Read M, Abbas A, Sallum R, Müller-Stich BP, Perez D, Biebl M, Egberts J-H, van Hillegersberg R, Bruns CJ (2021) Robotic-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy (RAMIE) for esophageal cancer training curriculum-a worldwide Delphi consensus study. Dis Esophagus 35:doab055

Dell’Oglio P, Turri F, Larcher A, D’Hondt F, Sanchez-Salas R, Bochner B, Palou J, Weston R, Hosseini A, Canda AE, Bjerggaard J, Cacciamani G, Olsen KØ, Gill I, Piechaud T, Artibani W, van Leeuwen PJ, Stenzl A, Kelly J, Dasgupta P, Wijburg C, Collins JW, Desai M, van der Poel HG, Montorsi F, Wiklund P, Mottrie A (2022) Definition of a structured training curriculum for robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal ileal conduit in male patients: a Delphi consensus study led by the erus educational board. Eur Urol Focus 8:160–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2020.12.015

Collins JW, Marcus HJ, Ghazi A, Sridhar A, Hashimoto D, Hager G, Arezzo A, Jannin P, Maier-Hein L, Marz K, Valdastri P, Mori K, Elson D, Giannarou S, Slack M, Hares L, Beaulieu Y, Levy J, Laplante G, Ramadorai A, Jarc A, Andrews B, Garcia P, Neemuchwala H, Andrusaite A, Kimpe T, Hawkes D, Kelly JD, Stoyanov D (2021) Ethical implications of AI in robotic surgical training: a Delphi consensus statement. Eur Urol Focus. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2021.04.006

van der Schans EM, Verheijen PM, el Moumni M, Broeders IAMJ, Consten ECJ (2022) Evaluation of the learning curve of robot-assisted laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy. Surg Endosc 36:2096–2104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08496-w

Carter-Brooks CM, Du AL, Bonidie MJ, Shepherd JP (2018) The impact of a dedicated robotic team on robotic-assisted sacrocolpopexy outcomes. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 24:13–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000413

van Zanten F, Schraffordt Koops SE, Pasker-De Jong PCM, Lenters E, Schreuder HWR (2019) Learning curve of robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpo(recto)pexy: a cumulative sum analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 221:483.e1-483.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.05.037

Evans S, McCarter M, Abimbola O, Myers EM (2021) Enhanced recovery and same-day discharge after minimally invasive sacrocolpopexy. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 27:740–745. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000001043

Kisby CK, Polin MR, Visco AG, Siddiqui NY (2019) Same-day discharge after robotic-assisted sacrocolpopexy. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 25:337–341. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000573

Lloyd JC, Guzman-Negron J, Goldman HB (2018) Feasibility of same day discharge after robotic assisted pelvic floor reconstruction. Can J Urol 25:9307–9312

Faucheron JL, Trilling B, Barbois S, Sage PY, Waroquet PA, Reche F (2016) Day case robotic ventral rectopexy compared with day case laparoscopic ventral rectopexy: a prospective study. Tech Coloproctol 20:695–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-016-1518-3

Trilling B, Sage PY, Reche F, Barbois S, Waroquet PA, Faucheron JL (2018) Early experience with ambulatory robotic ventral rectopexy. J Visc Surg 155:5–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2017.05.005

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Laura J. Ninger, ELS (Ninger Medical Communications, LLC) for professional English language revision. Tommaso Simoncini had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università di Pisa within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The project was funded with research funds from the University of Pisa to Tommaso Simoncini.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TS and AP: wrote the manuscript. TS and GN: organized the project, chaired the organizing committee and the scientific committee, and participated in the Delphi process. ECJC, HD, GM, CR, and SSK: formed the scientific committee and participated in the Delphi process. MA, JA, CB, ALAB, SB, GC, MC, JD, EE-B, J-LF, BG, DH, RJ, PM, LM, JM, CR, BAO, and SS: participated in the Delphi process. AP and MMMG: set up and managed the Google module system to perform the electronic Delphi process and analyzed the results. MC, BF, AG, ER, and AS: assisted with selection of participants, creation of the statements, and final elaboration of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Alexander L.A. Bloemendaal is proctor and speaker for Intuitive Surgical, TelaBio, and FascioTens. Stephan Buse is proctor for Intuitive Surgical. Ralf Joukhadar is proctor and speaker for Intuitive Surgical. Christl Reisenauer received speaker’s honoraria from Intuitive Surgical, Contura/Axonics, and Boston Scientific. Tommaso Simoncini has received consulting fees from Abbott, Astellas, Gedeon Richter, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Sojournix, Estetra, Mithra, Actavis, Medtronic, Shionogi, and Applied Medical and has received speakers’ honoraria from Shionogi, Gedeon Richter, Intuitive Surgical, Applied Medical, and Theramex. Steven Schraffordt Koops is proctor for Intuitive Surgical. Andrea Panattoni, Mustafa Aktas, Jozef Ampe, Cornelia Betschart, Alexander L.A. Bloemendaal, Giuseppe Campagna, Marta Caretto, Mauro Cervigni, Esther C.J. Consten, Hugo H. Davila, Jean Dubuisson, Eloy Espin-Basany, Bernardina Fabiani, Jean-Luc Faucheron, Andrea Giannini, Brooke Gurland, Dieter Hahnloser, Paolo Mannella, Liliana Mereu, Jacopo Martellucci, Guillaume Meurette, Maria Magdalena Montt Guevara, Carlo Ratto, Barry A. O'Reilly, Eleonora Russo, Shahab Siddiqi, Alessandro Sturiale, and Gabriele Naldini have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Simoncini, T., Panattoni, A., Aktas, M. et al. Robot-assisted pelvic floor reconstructive surgery: an international Delphi study of expert users. Surg Endosc 37, 5215–5225 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-023-10001-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-023-10001-4