Abstract

Background

In inguinal hernia repair, chronic pain must be expected in 10–12% of cases. Around one-quarter of patients (2–4%) experience severe pain requiring treatment. The risk factors for chronic pain reported in the literature include young age, female gender, perioperative pain, postoperative pain, recurrent hernia, open hernia repair, perioperative complications, and penetrating mesh fixation. This present analysis of data from the Herniamed Hernia Registry now investigates the influencing factors for chronic pain in male patients after primary, unilateral inguinal hernia repair in TAPP technique.

Methods

In total, 20,004 patients from the Herniamed Hernia Registry were included in uni- and multivariable analyses. For all patients, 1-year follow-up data were available.

Results

Multivariable analysis revealed that onset of pain at rest, on exertion, and requiring treatment was highly significantly influenced, in each case, by younger age (p < 0.001), preoperative pain (p < 0.001), smaller hernia defect (p < 0.001), and higher BMI (p < 0.001). Other influencing factors were postoperative complications (pain at rest p = 0.004 and pain on exertion p = 0.023) and penetrating compared with glue mesh fixation techniques (pain on exertion p = 0.037).

Conclusions

The indication for inguinal hernia surgery should be very carefully considered in a young patient with a small hernia and preoperative pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

After mesh-based inguinal hernia repair 10–12% of patients experience at least a level of moderate pain that impacts daily activities [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Chronic pain is defined as any pain reported by the patient at or beyond 3 months postoperatively [2]. More than one-quarter of these patients (2–4%) have moderate to severe pain [2, 5, 6]. Risk factors for chronic postoperative inguinal pain include young age, female gender, high preoperative pain, early high postoperative pain, recurrent hernia, and open hernia repair [1,2,3,4,5,6].

In all statements in the guidelines of the international hernia societies, laparo-endoscopic techniques are associated with less chronic pain than the Lichtenstein repair [7,8,9,10,11]. However, after laparo-endoscopic inguinal hernia repair, 2–5% of patients may still suffer from persistent pain influencing everyday activities, and about 0.4% are referred to pain clinics [12].

On the basis of three meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [13,14,15] mesh fixation in total extraperitoneal patch plasty (TEP) can only be recommended in large medial/direct (EHS MIII) hernias [10].

In the Guidelines of the International Endohernia Society, a recommendation is given for consideration of non-fixation of the mesh in transabdominal preperitoneal patch plasty (TAPP) inguinal hernia repair in types LI, II and MI, II (EHS classification) [9, 10]. For TAPP repair of larger defects (LIII, MIII), the mesh should be fixed [9, 10]. In TAPP inguinal hernia repair, mesh fixation is still used in 66.1% of all primary unilateral cases in men [16].

Considering the fact that five meta-analyses [17,18,19,20,21] compared non-penetrating vs. mechanical mesh fixation, high-quality evidence could be expected. However, the meta-analyses can only conclude that the evidence is mostly of low or moderate quality, or that more high-quality multicenter studies are needed [22]. In view of the guidelines, fibrin glue should be considered for fixation to minimize the risk of postoperative acute and chronic pain [9, 10].

In a nationwide registry-based study, no differences were found in the frequency of recurrence and chronic pain between permanent and no/non-permanent fixation of the mesh in endoscopic inguinal hernia repair [23].

Another registry-based study from the Danish Hernia Database also found no difference in chronic pain after mesh fixation with fibrin glue vs. tacks in TAPP inguinal hernia repair [24].

The following analysis of data from the Herniamed Registry now investigates the influencing factors for chronic pain in male patients after primary, unilateral inguinal hernia repair in TAPP technique.

Methods

As of October 10, 2016, 577 participating hospitals and office-based surgeons mainly from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland had entered prospective data into the internet-based Herniamed Hernia Registry on their patients who had undergone routine hernia surgery and signed an informed consent agreeing to participate [25]. As part of the information provided to patients regarding participation in the Herniamed Quality Assurance Study and signing the informed consent declaration, all patients are informed that the treating hospital or medical practice would like to be informed about any problems occurring after the operation and that the patient has the opportunity to attend for clinical examination.

This present study analyzed the prospective data collected for all male patients who had been operated on with an endoscopic TAPP technique for repair of a primary unilateral inguinal hernia in the period September 01, 2009, up to and including September 01, 2015. On 1-year follow-up, the general practitioners and patients were asked through questionnaire about any pain at rest, pain on exertion, and chronic pain requiring treatment. If chronic pain is reported by the general practitioner or patient, patients can be requested to attend for clinical examination. A recent publication has provided impressive evidence of the role of patient-reported outcomes for the identification of chronic pain rates after groin hernia repair [26]. Only those patients for whom 1-year follow-up results were available were included in the analysis. Other inclusion criteria included age ≥ 16 years and only medial/lateral/combined types of inguinal hernia based on the EHS classification [27].

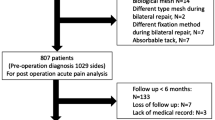

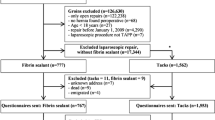

In total, 20,004 were included in uni- and multivariable analyses for investigation of the influencing factors for the development of chronic pain following TAPP inguinal hernia repair (Fig. 1).

All analyses were performed with the software SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA) and intentionally calculated to a full significance level of 5%, i.e., they were not corrected in respect of multiple tests, and each p value ≤ 0.05 represents a significant result.

To first discern differences between the groups in unadjusted analyses, Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical outcome variables, and the robust t test (Satterthwaite) for continuous variables. For mesh size (cm2), a logarithmic transformation was applied and the re-transformed mean and range of dispersion are given.

To identify influence factors in multivariable analyses, binary logistic regression models for pain at rest, pain on exertion, and chronic pain requiring treatment were used. Potential influence factors were ASA score (I/II/III/IV), age (years), BMI (kg/m2), mesh size (cm2), defect size (I/II/III), risk factors (yes/no), preoperative pain (yes/no/unknown), EHS classification (lateral/medial/combined), postoperative complication (yes/no), and mesh fixation (no fixation/tacker/glue). Estimates for odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval based on the Wald test were given. For influence variables with more than two categories, pairwise odds ratios were given. For age (years) the 10-year OR estimate, for BMI (kg/m2) the five-point OR estimate, and for mesh size (cm2) the 10-point OR estimate were given. The results are presented in tabular form, sorted by descending impact.

Results

In total, 20,004 patients were included in the analysis exploring the influence exerted by the fixation technique as well as by other influencing variables on the rate of pain at rest, pain on exertion, and chronic pain requiring treatment (Fig. 1). Of these, 8799 patients had no fixation (44.0%), 6387 (31.9%) only tacker fixation, and 4818 patients (24.1%) only glue fixation.

The patient group in whom the mesh was fixed with a tacker was on average the oldest and had also the highest BMI (Table 1). While there were significant differences in age and BMI between the two groups due to the large patient number, these were not clinically relevant. The meshes in the patient group with no fixation were smaller (Table 1). Besides, meshes with glue fixation had the fewest (8.5%) and meshes with tacker fixation the most (14.1%) ASA III/IV patients (Table 2). The operations with no fixation were most commonly encountered for small hernia defect sizes (17.4%). As regards the defect localization, for lateral EHS classification no or only glue fixation was mainly used, whereas for medial EHS classification tacker fixation was most common (Table 2). Preoperative pain was less common among patients with tacker mesh fixation (59.4%) than in patients with glue mesh fixation (67.3%) or no mesh fixation (66.3%). Drain placement was most commonly used for patients with no mesh fixation (8.4%). In terms of the risk factors, mesh fixation with tackers or glue was more common in patients who continued to take platelet aggregation inhibitors (6.2 vs. 7.8% and 7.6%).

Unadjusted analysis of the relationship between the fixation technique and the intra- and postoperative complications, recurrence rate as well as pain at rest, on exertion, and requiring treatment on 1-year follow-up is given in detail in Table 3. For postoperative complications, pain on exertion and pain requiring treatment differences are identified in relation to the fixation technique used. For postoperative complication these are largely due to an increased seroma rate (no fixation 0.7% vs. tacker fixation 2.1% vs. glue fixation 3.9%). For operations with no mesh fixation, the rate of pain on exertion (no fixation 10.1% vs. tacker fixation 9.4% vs. glue fixation 8.8%) and pain requiring treatment (no fixation 3.0% vs. tacker fixation 2.4% vs. glue fixation 2.3%) was somewhat higher than in the groups with tacker or glue mesh fixation.

Tables 2 and 3 show, in some cases, significant differences in the influencing factors and thus also in outcomes in relation to fixation vs. non-fixation. Accordingly, the unadjusted analysis results permit only limited comparability and therefore call for multivariable analysis.

Multivariable analysis

Pain at rest on 1-year follow-up

The results of analysis of pain at rest on 1-year follow-up are summarized in Table 4 (model fitting: p < 0.001). Pain at rest was highly significantly influenced by the presence of preoperative pain, by age, BMI, and the hernia defect size (in each case p < 0.001). In higher age (10-year OR 0.880 [0.839; 0.924]; p < 0.001) the risk of pain at rest was lower, whereas for higher BMI (five-point OR 1.225 [1.124; 1.334]; p < 0.001), presence of preoperative pain (yes vs. no: OR 1.862 [1.574; 2.201]; p < 0.001), and smaller hernia defect (I vs. III: OR 1.619 [1.298; 2.021]; p < 0.001) it was higher. Additionally, postoperative complications led also to a higher risk of onset of pain at rest (OR 1.613 [1.162; 2.239]; p = 0.004). There was no evidence of the fixation technique having any influence on the risk of onset of pain at rest.

Pain on exertion on 1-year follow-up

Pain on exertion on 1-year follow-up, whose analysis results are summarized in Table 5 (model fitting: p < 0.001), was significantly influenced by age, preoperative pain, hernia defect size, BMI (in each case p < 0.001), mesh size (p = 0.031), postoperative complications (p = 0.023), and the fixation technique (p = 0.037). A higher age (10-year OR 0.796 [0.768; 0.825]; p < 0.001) led to a lower risk and preoperative pain (yes vs. no: OR 1.516 [1.349; 1.705]; p < 0.001) to a higher risk of onset of pain on exertion. Small defect sizes (I vs. III: OR 1.605 [1.354; 1.902]; p < 0.001), higher BMI (five-point OR 1.180 [1.104; 1.260]; p < 0.001), and onset of postoperative complications (yes vs. no: OR 1.364 [1.045; 1.780]; p = 0.023) increased the risk of pain on exertion.

The use of a larger mesh reduced the risk of pain on exertion (10-point OR 0.971 [0.946; 0.997]; p = 0.031). There was also evidence of the influence of the fixation technique, (p = 0.037), revealing that tacker compared with glue fixation led to a higher rate of pain on exertion (OR 1.192 [1.043; 1.362]; p = 0.010).

Chronic pain requiring treatment on 1-year follow-up

The results of analysis of the influencing factors for pain requiring treatment are shown in Table 6 (model fitting: p < 0.001). Here, too, the risk of onset of chronic pain requiring treatment was highly significantly affected by the hernia defect size, age, BMI, and preoperative pain (in each case p < 0.001). The rate of chronic pain requiring treatment was, in particular, negatively influenced by small defect sizes (I vs. III: OR 1.996 [1.482; 2.688]; p < 0.001), higher BMI (five-point OR 1.319 [1.181; 1.473]; p < 0.001) as well as by preoperative pain (yes vs. no: OR 1.819 [1.441; 2.296]; p < 0.001). On the other hand, higher age (10-year OR 0.842 [0.788; 0.899]; p < 0.001) resulted in a lower risk of chronic pain requiring treatment.

Additional analysis

An additional analysis was included to show, not only qualitatively but also quantitatively, the results for the impact of age and BMI on chronic pain. This revealed that age ≤ 40 years was associated with the highest rates of pain at rest (6.4%), pain on exertion (13.7%), and pain requiring treatment (3.6%) on 1-year follow-up. Patients between > 40 and 60 years had mean pain rates (5.5, 11.6, and 3.1%, respectively) and patients > 60 years had the lowest pain rates (3.9, 6.0, and 1.8%, respectively). Patients with BMI of 18.5–24.9 (WHO classification: normal weight) had the lowest pain rates (4.2, 8.5, and 2.1%, respectively), those with BMI between 25.0 and 29.0 (WHO classification: overweight) had average rates (5.5, 10.0, and 2.7%, respectively) and those with BMI ≥ 30 (WHO classification: obesity) the highest pain rates (6.3, 11.5 , and 4.1%, respectively).

Discussion

The present analysis of data from the Herniamed Hernia Registry for 20,004 male patients with elective primary, unilateral inguinal hernia repair in TAPP technique and with 1-year follow-up results has once again confirmed that, as reported in the literature, a pain at rest rate of 4–5%, pain on exertion of 8–10%, and pain requiring treatment of 2–3% must be expected [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In this selected patient group with laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair of exclusively male patients with primary unilateral inguinal hernia, it was also demonstrated that, as in the literature [1,2,3,4,5,6], young age (≤ 40 years) and preoperative pain are important influencing factors for onset of chronic pain. The present multivariable analysis has revealed that pain at rest, pain on exertion, and chronic pain requiring treatment was highly affected by preoperative pain and young age. But that was also true for small hernia defects. For a small hernia defect the risk of pain at rest, on exertion, and requiring treatment appeared to be highly significantly greater than for a large hernia defect. One explanation for this could be that a patient who is willing to undergo surgery for even a smaller inguinal hernia is more sensitive to pain [1], and already experiences preoperative pain. But the issue of the indication for surgery must also be addressed. Was the inguinal pain really related to a small inguinal hernia or was this due to other causes that also persisted after inguinal hernia repair? Other causes of inguinal pain must be effectively ruled out.

This clearly demonstrates that young patients with a small inguinal hernia (EHS I: < 1.5 cm) and inguinal pain are at highest risk for onset of chronic pain following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Accordingly, a well-founded indication for surgery is of strictly crucial importance for these patients. The patient should definitely be made aware of this before signing the declaration of informed consent form for surgery. If the indication is correct, the operation should be performed in accordance with the evidence-based guidelines for the TAPP technique [9, 10].

Likewise, patients with higher BMI value (≥ 25.0) had a highly significant influence on the risk of pain at rest, on exertion, and chronic pain requiring treatment after TAPP operation. Overweight or obesity, in particular in male patients makes additional demands on the surgeon during conduct of TAPP. Therefore commensurate caution must be exercised when performing surgery for overweight patients.

In addition to the most important influencing factors for onset of chronic pain after laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery (young age, preoperative pain, small hernia defect, and higher BMI), there are other factors affecting onset of chronic pain. These include postoperative complications and the use of penetrating tackers for mesh fixation. As demonstrated in five meta-analyses, the use of penetrating mesh fixation compared with glue fixation led to significantly more chronic inguinal pain [17,18,19,20,21], but the evidence is mostly of low or moderate quality. Unlike the aforementioned meta-analyses, on comparing tack mesh fixation vs. non-fixation Sajid et al. [15] did not find any difference in the chronic pain rates. Likewise, a registry-based Danish study did not find any difference in chronic pain rates after TAPP operation on comparing mesh fixation with fibrin glue vs. tacks [24]. In our study, the influence of penetrating tacks on chronic pain was only confirmed for pain on exertion on comparing non-fixation vs. tack fixation. In their systematic review, Lederhuber et al. [22] concluded that there is still a lack of high-quality evidence for differences between the assessed mesh fixation techniques. Therefore, more high-quality multicenter studies are needed [22]. The findings of our study at least suggest that other factors, such as a small hernia, preoperative pain, younger age, and higher BMI, have a greater impact on the development of chronic pain than does the fixation technique.

Likewise, postoperative complications can trigger inguinal pain. Therefore, an appropriate response must be taken to any development of postoperative complications after TAPP operation to prevent the onset of chronic inguinal pain.

The potential weakness of this study is its non-randomization and the voluntary participation in the internet-based registration. These could lead to selection bias, which can be balanced by the large case number of the study. Furthermore, the registry does not contain any data on how the peritoneum was closed.

In summary, it can be stated that there are several influencing factors for pain at rest, on exertion, and chronic pain requiring treatment following primary unilateral inguinal hernia repair in male patients in TAPP technique. Younger patient age, preoperative pain, smaller hernia defect size, and higher BMI value have a highly significant influence. Other potentially influencing factors are penetrating mesh fixation and development of postoperative complications. Through a well-founded indication, and observance of the technical guidelines for evidence-based conduct of TAPP, it may be possible to prevent chronic pain after TAPP operation.

References

Aasvang EK, Gmaehle E, Hansen J, Gmaehle B, Forman JL, Schwarz J, Bittner R, Kehlet H (2010) Predictive risk factors for persistent postherniotomy pain. Anesthesiology 112:957–969

Nienhuijs S, Staal E, Strobbe L, Rosman C, Groenewoud H, Bleichrodt R (2007) Chronic pain after mesh repair of inguinal hernia: a systematic review. Am J Surg 194:394–400. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.02.012

Aasvang E, Kehlet H (2005) Surgical management of chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 92(7):795–801

Alfieri S, Amid PK, Campanelli G, Izard G, Kehlet H, Wijsmuller AR, Di Miceli D, Doglietto GB (2011) International guidelines for prevention and management of post-operative chronic pain following inguinal hernia surgery. Hernia 15:239–249. doi:10.1007/s10029-011-0798-9

O’Dwyer PJ, Alani A, McConnachie A (2005) Groin hernia repair: postherniorrhaphy pain. World J Surg 29:1062–1065. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-7903-0

Hakeem A, Shanmugam V (2011) Inguinodynia following Lichtenstein tension-free hernia repair: a review. World J Gastroenterol 17(14):1791–1796. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i14.1791

Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, Bouillot JL, Campanelli G, Conze J, de Lange D, Fortelny R, Heikkinen T, Kingsnorth A, Kukleta J, Morales-Conde S, Nordin P, Schumeplick V, Smedberg S, Smietanski M, Weber G, Miserez M (2009) European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia 13:343–403. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0529-7

Miserez M, Peeters E, Aufenacker T, Bouillot JL, Campanelli G, Conze J, Fortelny R, Heikkinen T, Jorgensen LN, Kukleta J, Morales-Conde S, Nordin P, Schumpelick V, Smedberg S, Smietanski M, Weber G, Simons MP (2014) Update with level 1 studies of the European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia 18:151–163. doi:10.1007/s10029-014-1236-6

Bittner R, Arregui ME, Bisgaard T, Dudai M, Ferzli GS, Fitzgibbons RJ, Fortelny RH, Klinge U, Köckerling F, Kuhry E, Kukleta J, Lomanto D, Misra MC, Montgomery A, Morales-Conde S, Reinpold W, Rosenberg J, Sauerland S, Schug-Paß C, Singh K, Timoey M, Weyhe D, Chowbey P (2011) Guidelines for laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal Hernia [International Endohernia Society (IEHS)]. Surg Endosc 25:2773–2843. doi:10.1007/s00464-011-1799-6

Bittner R, Montgomery MA, Arregui E, Bansal V, Bingener J, Bisgaard T, Buhck H, Dudai M, Ferzli GS, Fitzgibbons RJ, Fortelny RH, Grimes KL, Klinge U, Köckerling F, Kumar S, Kukleta J, Lomanto D, Misra MC, Morales-Conde S, Reinpold W, Rosenberg J, Singh K, Timoney M, Weyhe D, Chowbey P (2015) Update of guidelines on laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia (International Endohernia Society). Surg Endosc 29:289–321. doi:10.1007/s00464-014-3917-8

Poelman MM, van den Heuvel B, Deelder JD, Abis GSA, Beudeker N, Bittner R, Campanelli G, van Dam D, Dwars BJ, Eker HH, Fingerhut A, Khatkov I, Koeckerling F, Kukleta JF, Miserez M, Montgomery A, Munoz Brands RM, Morales Conde S, Muysoms FE, Soltes M, Tromp W, Yavuz Y, Bonjer HJ (2013) EAES Consensus Development Conference on endoscopic repair of groin hernias. Surg Endosc 27:3505–3519. doi:10.1007/s00464-013-3001-9

Linderoth G, Kehlet H, Aasvang EK, Werner MU (2011) Neurophysiological characterization of persistent pain after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 15:521–529. doi:10.1007/s10029-011-0815-z

Tam KW, Liang HH, Chai CY (2010) Outcomes of staple fixation of mesh versus nonfixation in laparoscopic total extraperitoneal inguinal repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Word J Surg 34:3065–3074. doi:10.1007/s00268-010-0760-5

Teng YJ, Pan SM, Liu YL, Yang KH, Zhang YC, Tian JH, Han JX (2011) A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of fixation versus nonfixation of mesh in laparoscopic total extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. Surg Endosc 25(9):2849–2858. doi:10.1007/s00464-011-1668-3

Sajid MS, Ladwa N, Kalra L. Hutson K, Sains P, Baig MK (2012) A meta-analysis examining the use of tacker fixation versus no-fixation of mesh in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Int J Surg 10(5):224–231. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.03.001

Mayer F, Niebuhr H, Lechner M, Dinnewitzer A, Köhler G, Hukauf M, Fortelny RH, Bittner R, Köckerling F (2016) When is mesh fixation in TAPP-repair of primary inguinal hernia repair necessary? The register-based analysis of 11,230 cases. Surg Endosc 30(10):4363–4371. doi:10.1007/s00464-016-4754-8

Kaul A, Hutfless S, Le H, Hamed SA, Tymitz K, Nguyen H, Marohn MR (2012) Staple versus fibrin glue fixation in laparoscopic total extraperitoneal repair of inguinal hernia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 26(5):1269–1278. doi:10.1007/s00464-011-2025-2

Shah NS, Fullwood C, Siriwardena AK, Sheen AJ (2014) Mesh fixation at laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis comparing tissue glue and tack fixation. World J Surg 38(10):2558–2570. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2547-6

Li J, Ji Z, Zang W (2015) Staple fixation against adhesive fixation in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 25(6):471–477. doi:10.1079/SLE.0000000000000214

Antoniou SA, Köhler G, Antoniou GA, Muysoms FE, Pointner R, Granderath FA (2016) Meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing nonpenetrating vs mechanical mesh fixation in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Am J Surg 211(1):239–249.e2. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.06.008

Shi Z, Fan X, Zai S, Zong X, Huang D, Fibrin glue versus staple for mesh fixation in laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal repair of inguinal hernia: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Surg Endosc 31:527–537. doi:10.1007/s00464-016-5039-y

Lederhuber H, Stiede F, Axer S, Dahlstrand U (2017) Mesh fixation in endoscopic inguinal hernia repair: evaluation of methodology based on a systematic review of randomized clinical trails. Surg Endosc. doi:10.1007/s00464-017-559-x

Gutlic N, Rogmark P, Nordin P, Petersson U, Montgomery A (2016) Impact of mesh fixation on chronic pain in total extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair (TEP): a nationwide register-based study. Ann Surg 263(6):1199–1206. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001306

Andresen K, Fenger AQ, Burcharth J, Pommergaard HC, Rosenberg J (2017) Mesh fixation methods and chronic pain after transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) inguinal hernia surgery: a comparison between fibrin sealant and tacks. Surg Endoc. doi:10.1007/s00464-017-5454-8

Stechemesser B, Jacob DA, Schug-Paß C, Köckerling F (2012) Herniamed: an internet-based registry for outcome research in hernia surgery. Hernia 16(3):269–276. doi:10.1007/s10029-012-0908-3

Haapaniemi S, Nilsson E (2002) Recurrence and pain three years after groin hernia repair. Validation of postal questionnaire and selective physical examination as a method of follow-up. Eur J Surg 168:22–28. doi:10.1080/110241502317307535

Miserez M, Alexandre JH, Campanelli G, Corcione F, Cuccurullo D, Pascual MH, Hoeferlin A, Kingsnorth AN, Mandala V, Palot JP, Schumpelick V, Simmermacher RK, Stoppa R, Flament JB (2007) The European hernia society groin hernia classification: simple and easy to remember. Hernia 11(2):113–116. doi:10.1007/s10029-007-0198-3

Acknowledgements

Ferdinand Köckerling received grants to fund the Herniamed Registry from Johnson & Johnson, Norderstedt; Karl Storz, Tuttlingen; PFM medical, Cologne; Dahlhausen, Cologne; B Braun, Tuttlingen; MenkeMed, Munich; and Bard, Karlsruhe.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

H. Niebuhr, F. Wegner, M. Hukauf, M. Lechner, R. Fortelny, R. Bittner, C. Schug-Pass have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Appendix

Appendix

Herniamed Study Group

Scientific board

Köckerling, Ferdinand (Chairman) (Berlin); Bittner, Reinhard (Rottenburg); Fortelny, René (Wien); Jacob, Dietmar (Berlin); Koch, Andreas (Cottbus); Kraft, Barbara (Stuttgart); Kuthe, Andreas (Hannover); Lammers, Bernhard (Neuss); Lippert, Hans (Magdeburg): Lorenz, Ralph (Berlin); Mayer, Franz (Salzburg); Niebuhr, Henning (Hamburg); Peiper, Christian (Hamm); Pross, Matthias (Berlin); Reinpold, Wolfgang (Hamburg); Simon, Thomas (Weinheim); Stechemesser, Bernd (Köln); Unger, Solveig (Chemnitz); Weyhe, Dirk (Oldenburg); Zarras, Konstantinos (Düsseldorf).

Participants

Ahmetov, Azat (Saint-Petersburg); Alapatt, Terence Francis (Frankfurt/Main); Albayrak, Nurretin (Herne); Amann, Stefan (Neuendettelsau); Anders, Stefan (Berlin); Anderson, Jürina (Würzburg); Antoine, Dirk (Leverkusen); Apfelstedt, Heinrich (Solingen); Arndt, Anatoli (Elmshorn); Aschenbrenner, Michael (Spittal/Drau); Asperger, Walter (Halle); Avram, Iulian (Saarbrücken); Baikoglu-Endres, Corc (Weißenburg i. Bay.); Bandowsky, Boris (Damme); Barkus; Jörg (Velbert); Becker, Matthias (Freital); Behrend, Matthias (Deggendorf); Berkhoff, Christian (Fulda); Beuleke, Andrea (Burgwedel); Birk, Dieter (Bietigheim-Bissingen); Bittner, Reinhard (Rottenburg); Blaha, Pavel (Zwiesel); Blumberg, Claus (Lübeck); Böckmann, Ulrich (Papenburg); Böhle, Arnd Steffen (Bremen); Bolle, Ludger (Berlin); Borchert, Erika (Grevenbroich); Born, Henry (Leipzig); Brabender, Jan (Köln); Breitenbuch von, Philipp (Radebeul); Brož, Miroslav (Ebersbach); Brückner, Torsten (Gießen); Brütting, Alfred (Erlangen); Buchert, Annette (Mallersdorf-Pfaffenberg); Buchholz, Torsten (Aurich); Budzier, Eckhard (Meldorf); Burchett, Bert (Teterow); Burghardt, Jens (Rüdersdorf); Cejnar, Stephan-Alexander (München); Chirikov, Ruslan (Dorsten); Claußnitzer, Christian (Ulm); Comman, Andreas (Bogen); Crescenti, Fabio (Verden/Aller); Daniels, Thies (Hamburg); Dapunt, Emanuela (Bruneck); Decker, Georg (Berlin); Demmel, Michael (Arnsberg); Descloux, Alexandre (Baden); Deusch, Klaus-Peter (Wiesbaden); Dick, Marcus (Neumünster); Dieterich, Klaus (Ditzingen); Dietz, Harald (Landshut); Dittmann, Michael (Northeim); Drummer, Bernhard (Forchheim); Eckermann, Oliver (Luckenwalde); Eckhoff (Jörn /Hamburg); Ehmann, Frank (Grünstadt); Eisenkrein, Alexander (Düren); Elger, Karlheinz (Germersheim); Engelhardt, Thomas (Erfurt); Erichsen, Axel (Friedrichshafen); Eucker, Dietmar (Bruderholz); Fackeldey, Volker (Kitzingen); Faddah, Yousif (Kamenz); Farke, Stefan (Delmenhorst); Faust, Hendrik (Emden); Federmann, Georg (Seehausen); Fiedler, Michael (Eisenberg); Fikatas, Panagiotis (Berlin); Firl, Michaela (Perleberg); Fischer, Ines (Wiener Neustadt); Fleischer, Sabine (Dinslaken); Fortelny, René H. (Wien); Franczak, Andreas (Wien); Franke, Claus (Düsseldorf); Frankenberg von, Moritz (Salem); Frehner, Wolfgang (Ottobeuren); Friedhoff, Klaus (Andernach); Friedrich, Jürgen (Essen); Frings, Wolfram (Bonn); Fritsche, Ralf (Darmstadt); Frommhold, Klaus (Coesfeld); Frunder, Albrecht (Tübingen); Fuhrer, Günther (Reutlingen); Garlipp, Ulrich (Bitterfeld-Wolfen); Gassler, Harald (Villach); Gawad, Karim A. (Frankfurt/Main); Gehrig, Tobias (Sinsheim); Gerdes, Martin (Ostercappeln); Germanov, German (Halberstadt); Gilg, Kai-Uwe (Hartmannsdorf); Glaubitz, Martin (Neumünster); Glauner-Goldschmidt, Kerstin (Werne); Glutig, Holger (Meissen); Gmeiner, Dietmar (Bad Dürrnberg); Göring, Herbert (München); Grebe, Werner (Rheda-Wiedenbrück); Grothe, Dirk (Melle); Günther, Thomas (Dresden); Gürtler, Thomas (Zürich); Hache, Helmer (Löbau); Hämmerle, Alexander (Bad Pyrmont); Haffner, Eugen (Hamm); Hain, Hans-Jürgen (Gross-Umstadt); Halter, Christian Jörn (Recklinghausen); Hammans, Sebastian (Lingen); Hampe, Carsten (Garbsen); Hanke, Stefan (Halle); Harrer, Petra (Starnberg); Hartung, Peter (Werne); Heinzmann, Bernd (Magdeburg); Heise, Joachim Wilfried (Stolberg); Heitland, Tim (München); Helbling, Christian (Uznach/Schweiz); Hellinger, Achim (Fulda); Hempen, Hans-Günther (Cloppenburg); Henneking, Klaus-Wilhelm (Bayreuth); Hennes, Norbert (Duisburg); Herdter, Christian (Gelsenkirchen); Hermes, Wolfgang (Weyhe); Herzing, Holger (Höchstadt); Hessler, Christian (Bingen); Heuer, Matthias (Herten); Hildebrand, Christiaan (Langenfeld); Höferlin, Andreas (Mainz); Hoffmann, Henry (Basel); Hoffmann, Michael (Kassel); Hofmann, Eva M. (Frankfurt/Main); Horbach, Thomas (Fürth); Hornung, Frederic (Wolfratshausen); Hudak, Attila (Suhl); Hübel-Abe, Jan (Ilmenau); Hügel, Omar (Hannover); Hüttemann, Martin (Oberhausen); Hüttenhain, Thomas (Mosbach); Hunkeler, Rolf (Zürich); Imdahl, Andreas (Heidenheim); Iseke, Udo (Duderstadt); Isemer, Friedrich-Eckart (Wiesbaden); Jablonski, Herbert Gustav (Sögel); Jacob, Dietmar (Berlin); Jansen-Winkeln, Boris (Leipzig); Jantschulev, Methodi (Waren); Jenert, Burghard (Lichtenstein); Jugenheimer, Michael (Herrenberg); Junge, Karsten (Aachen); Kaaden, Stephan (Neustadt am Rübenberge); Käs, Stephan (Weiden); Kahraman, Orhan (Hamburg); Kaiser, Christian (Westerstede); Kaiser, Gernot Maximilian (Kamp-Lintfort); Kaiser, Stefan (Kleinmachnow); Karch, Matthias (Eichstätt); Kasparek, Michael S. (München); Kastl, Sigrid (Braunau am Inn); Keck, Heinrich (Wolfenbüttel); Keller, Hans W. (Bonn); Kewer, Jans Ludolf (Tuttlingen); Kienzle, Ulrich (Karlsruhe); Kipfmüller, Brigitte (Köthen); Kirsch, Ulrike (Oranienburg); Klammer, Frank (Ahlen); Klatt, Richard (Hagen); Klein, Karl-Hermann (Burbach); Kleist, Sven (Berlin); Klobusicky, Pavol (Bad Kissingen); Kneifel, Thomas (Datteln); Knolle, Winfried (Pritzwalk); Knoop, Michael (Frankfurt/Oder); Knotter, Bianca (Mannheim); Koch, Andreas (Cottbus); Koch, Andreas (Münster); Köckerling, Ferdinand (Berlin); Köhler, Gernot (Linz); König, Oliver (Buchholz); Kornblum, Hans (Tübingen); Krämer, Dirk (Bad Zwischenahn); Kraft, Barbara (Stuttgart); Kratsch, Barthel (Dierdorf/Selters); Krausbeck, Matthias (Schwerin); Kreissl, Peter (Ebersberg); Krones, Carsten Johannes (Aachen); Kronhardt, Heinrich (Neustadt am Rübenberge); Kruse, Christinan (Aschaffenburg); Kube, Rainer (Cottbus); Kühlberg, Thomas (Berlin); Kühn, Gert (Freiberg); Kuhn, Roger (Gifhorn); Kusch, Eduard (Gütersloh); Kuthe, Andreas (Hannover); Ladberg, Ralf (Bremen); Ladra, Jürgen (Düren); Lahr-Eigen, Rolf (Potsdam); Lainka, Martin (Wattenscheid); Lalla, Thomas (Oschersleben); Lammers, Bernhard J. (Neuss); Lancee, Steffen (Alsfeld); Lange, Claas (Berlin); Langer, Claus (Göttingen); Laps, Rainer (Ehringshausen); Larusson, Hannes Jon (Pinneberg); Lauschke, Holger (Duisburg); Lechner-Puschnig, Marina (Klagenfurt am Wörthersee/Österreich); Leher, Markus (Schärding); Leidl, Stefan (Waidhofen/Ybbs); Leisten, Edith (Köln); Lenz, Stefan (Berlin); Liedke, Marc Olaf (Heide); Lienert, Mark (Duisburg); Limberger, Andreas (Schrobenhausen); Limmer, Stefan (Würzburg); Locher, Martin (Kiel); Loghmanieh, Siawasch (Viersen); Lorenz, Ralph (Berlin); Luedtke, Clinton (Kusel); Luther, Stefan (Wipperfürth); Luyken, Walter (Sulzbach-Rosenberg); Mallmann, Bernhard (Krefeld); Manger, Regina (Schwabmünchen); Maurer, Stephan (Münster); May, Jens Peter (Schönebeck); Mayer, Franz (Salzburg); Mayer, Jens (Schwäbisch Gmünd); Mellert, Joachim (Höxter); Menzel, Ingo (Weimar); Meurer, Kirsten (Bochum); Meyer, Moritz (Ahaus); Mirow, Lutz (Zwickau); Mittag-Bonsch, Martina (Crailsheim); Möbius, Ekkehard (Braunschweig); Mörder-Köttgen, Anja (Freiburg); Moesta, Kurt Thomas (Hannover); Mugomba, Gilbert (Dannenberg); Moldenhauer, Ingolf (Braunschweig); Morkramer, Rolf (Radevormwald); Mosa, Tawfik (Merseburg); Müller, Hannes (Schlanders); Müller, Volker (Nürnberg); Münzberg, Gregor (Berlin); Murr, Alfons (Vilshofen); Mussack, Thomas (St. Gallen); Nartschik, Peter (Quedlinburg); Nasifoglu, Bernd (Ehingen); Neumann, Jürgen (Haan); Neumeuer, Kai (Paderborn); Niebuhr, Henning (Hamburg); Nix, Carsten (Walsrode); Nölling, Anke (Burbach); Nostitz, Friedrich Zoltán (Mühlhausen); Obermaier (Straubing); Öz-Schmidt, Meryem (Hanau); Oldorf, Peter (Usingen); Olivieri, Manuel (Pforzheim); Passon, Marius (Freudenberg); Pawelzik, Marek (Hamburg); Pein, Tobias (Hameln); Peiper, Christian (Hamm); Peiper, Matthias (Essen); Pertl, Alexander (Spittal/Drau); Philipp, Mark (Rostock); Pickart, Lutz (Bad Langensalza); Pizzera, Christian (Graz); Pöllath, Martin (Sulzbach-Rosenberg); Pöschmann, Enrico (Thalwil); Possin, Ulrich (Laatzen); Prenzel, Klaus (Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler); Pröve, Florian (Goslar); Pronnet, Thomas (Fürstenfeldbruck); Pross, Matthias (Berlin); Puff, Johannes (Dinkelsbühl); Rabl, Anton (Passau); Raggi, Matthias Claudius (Stuttgart); Rapp, Martin (Neunkirchen); Reck, Thomas (Püttlingen); Reinpold, Wolfgang (Hamburg); Renter, Marc Alexander (Moers); Reuter, Christoph (Quakenbrück); Radke, Alexander (Thun/Zweisimmen); Richter, Jörg (Winnenden); Riemann, Kerstin (Alzenau-Wasserlos); Riesener, Klaus-Peter (Marl); Rodehorst, Anette (Otterndorf); Roehr, Thomas (Rödental); Rössler, Michael (Rüdesheim am Rhein); Roncossek (Bremerhaven); Rosniatowski, Rolland (Marburg); Roth Hartmut (Nürnberg); Sardoschau, Nihad (Saarbrücken); Sauer, Gottfried (Rüsselsheim); Sauer, Jörg (Arnsberg); Seekamp, Axel (Freiburg); Seelig, Matthias (Bad Soden); Seidel, Hanka (Eschweiler); Seiler, Christoph Michael (Warendorf); Seltmann, Cornelia (Hachenburg); Senkal, Metin (Witten); Shamiyeh, Andreas (Linz); Shang, Edward (München); Siemssen, Björn (Berlin); Sievers, Dörte (Hamburg); Silbernik, Daniel (Bonn); Simon, Thomas (Weinheim); Sinn, Daniel (Olpe); Sinner, Guy (Merzig); Sinning, Frank (Nürnberg); Smaxwil, Constatin Aurel (Stuttgart); Sörensen, Björn (Lauf an der Pegnitz): Sucke, Jochen Markus (Gießen); Syga, Günter (Bayreuth); Schabel, Volker (Kirchheim/Teck); Schadd, Peter (Euskirchen); Schassen von, Christian (Hamburg); Schattenhofer, Thomas (Vilshofen); Scheibel, Mike (Krefeld); Schelp, Lothar (Wuppertal); Scherf, Alexander (Pforzheim); Scheuerlein, Hubert (Paderborn); Scheyer, Mathias (Bludenz); Schilling, André (Kamen); Schimmelpenning, Hendrik (Neustadt in Holstein); Schinkel, Svenja (Kempten); Schmid, Michael (Gera); Schmid, Thomas (Innsbruck); Schmidt, Ulf (Mechernich); Schmitz, Heiner (Jena); Schmitz, Ronald (Altenburg); Schöche, Jan (Borna); Schoenen, Detlef (Schwandorf); Schrittwieser, Rudolf (Bruck an der Mur); Schroll, Andreas (München); Schubert, Daniel (Saarbrücken); Schüder, Gerhard (Wertheim); Schürmann, Rainer (Steinfurt); Schultz, Christian (Bremen-Lesum); Schultz, Harald (Landstuhl); Schulze, Frank P. (Mülheim an der Ruhr); Schulze, Thomas (Dessau-Roßlau); Schumacher, Franz-Josef (Oberhausen); Schwab, Robert (Koblenz); Schwandner, Thilo (Lich); Schwarz, Jochen Günter (Rottenburg); Schymatzek, Ulrich (Eitorf); Spangenberger, Wolfgang (Bergisch-Gladbach); Sperling, Peter (Montabaur); Staade, Katja (Düsseldorf); Staib, Ludger (Esslingen); Staikov, Plamen (Frankfurt am Main); Stamm, Ingrid (Heppenheim); Stark, Wolfgang (Roth); Stechemesser, Bernd (Köln); Steinhilper, Uz (München); Stengl, Wolfgang (Nürnberg); Stern, Oliver (Hamburg); Stöltzing, Oliver (Meißen); Stolte, Thomas (Mannheim); Stopinski, Jürgen (Schwalmstadt); Stratmann, Gerald (Goch); Straßburger, Harald (Alfeld); Stubbe, Hendrik (Güstrow/); Stülzebach, Carsten (Friedrichroda); Tepel, Jürgen (Osnabrück); Terzić, Alexander (Wildeshausen); Teske, Ulrich (Essen); Thasler, Wolfgang (München); Tichomirow, Alexej (Brühl); Tillenburg, Wolfgang (Marktheidenfeld); Timmermann, Wolfgang (Hagen); Tomov, Tsvetomir (Koblenz); Train, Stefan H. (Gronau); Trauzettel, Uwe (Plettenberg); Triechelt, Uwe (Langenhagen); Ulbricht, Wolfgang (Breitenbrunn); Ulcar, Heimo (Schwarzach im Pongau); Ungeheuer, Andreas (München); Unger, Solveig (Chemnitz); Utech, Markus (Gelsenkirchen); Verweel, Rainer (Hürth); Vogel, Ulrike (Berlin); Voigt, Rigo (Altenburg); Voit, Gerhard (Fürth); Volkers, Hans-Uwe (Norden); Volmer, Ulla (Berlin); Vossough, Alexander (Neuss); Wallasch, Andreas (Menden); Wallner, Axel (Lüdinghausen); Warscher, Manfred (Lienz); Warwas, Markus (Bonn); Weber, Jörg (Köln); Weber, Uwe (Eggenfelden); Weihrauch, Thomas (Ilmenau); Weiß, Heiko (Aue); Weiß, Johannes (Schwetzingen); Weißenbach, Peter (Neunkirchen); Werner, Uwe (Lübbecke-Rahden); Wessel, Ina (Duisburg); Weyhe, Dirk (Oldenburg); Wicht, Sebastian (Bützow); Wieber, Isabell (Köln); Wiens, Matthias (Affoltern); Wiesmann, Aloys (Rheine); Wiesner, Ingo (Halle); Withöft, Detlef (Neutraubling); Woehe, Fritz (Sangerhausen); Wolf, Claudio (Neuwied); Wolkersdörfer, Toralf (Pößneck); Yaksan, Arif (Wermelskirchen); Yildirim, Can (Lilienthal); Yildirim, Selcuk (Berlin); Zarras, Konstantinos (Düsseldorf); Zeller, Johannes (Waldshut-Tiengen); Zhorzel, Sven (Agatharied); Zuz, Gerhard (Leipzig).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Niebuhr, H., Wegner, F., Hukauf, M. et al. What are the influencing factors for chronic pain following TAPP inguinal hernia repair: an analysis of 20,004 patients from the Herniamed Registry. Surg Endosc 32, 1971–1983 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5893-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5893-2