Abstract

Background

The sentinel lymph node (SLN) procedure alter the strategy for the treatment of patients with colon cancer. New techniques emerge that may provide the surgeon with a tool for accurate intraoperative detection of the SLNs.

Methods

An SLN procedure of the sigmoid was used in six goats. During laparoscopy, the near-infrared dye indocyanine green (ICG) was injected into the subserosa of the sigmoid via a percutaneously inserted needle during four experiments and in the submucosa during colonoscopy in two experiments. After injection, the near-infrared features of a newly developed laparoscope were used to detect the lymph vessels and SLNs. At the end of the procedure, 2 h after injection, all the goats were killed, and autopsy was performed. During postmortem laparotomy, the sigmoid was removed and used for confirmation of ICG node uptake.

Results

In all the procedures, the lymph vessels were easily detected by their bright fluorescent emission. In the first two experiments, no lymph nodes were detected. In the subsequent four experiments, human serum albumin was added to the ICG solution before injection to enable better lymph node entrapment. In all four experiments, at least one bright fluorescent lymph node was found after the lymph vessels had been tracked by their fluorescent guidance. The mean time between injection and SLN identification was 10 min. In two cases, the SLNs were located up to 5 mm into the fat tissue of the mesentery and were not seen by regular vision of the laparoscope. By switching on the near-infrared features of the scope, a clear bright dot became visible, which increased in intensity after opening of the mesentery.

Conclusion

The SLN procedure for the sigmoid using near-infrared laparoscopy in the goat is a very promising technique. Achievements described in this report justify a clinical trial on the feasibility of ICG-guided SLN detection in humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Each year, approximately 500,000 patients die of colorectal malignancy [1]. The management of CRC has not changed for more than 100 years. The metastatic status of regional lymph nodes remains one of the most important factors for determining adjuvant chemotherapy.

Stages 1 and 2 colorectal cancer imply no lymph node involvement. However, up to 30% of the patients will experience locoregional recurrence or distant metastases and will die eventually of CRC. Therefore, standard surgery might not be sufficient for these patients [2]. A substantial portion of these patients will experience recurrences due to inadequate lymph node resection or missed nodal metastases at histologic examination [3].

With conventional hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, micrometastases are not detected. When the lymph node is multisectioned, micrometastases can be detected by immunohistochemistry and reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR). These techniques are labor and cost intensive, so it is highly impractical to ultrastage all the nodes in a given specimen. Several studies indicate that micrometastases are correlated with a significantly worse prognosis [4–7]. The sentinel lymph node (SLN) procedure could improve accurate staging by providing the pathologist with one or two lymph nodes for detailed evaluation. Also, a reliable sentinel node harvesting technique may alter the management in colorectal cancer treatment [2].

Several studies concerning the feasibility of SLN mapping in colon carcinoma have been published. The conclusion of a metaanalysis published in 2007 is that lymphatic mapping appears to be readily applicable. Its global sensitivity and specificity were, respectively, 70 and 81% [8].

Due to the wide variation of results shown in the literature, SLN mapping should be improved before this technique is routinely used in CRC. The most frequently used tracers in these studies are patent/isosulfan blue, radioactive tracers, or a combination of these. The use of these tracers poses several problems. Ink (patent/isosulfan blue), for example, is difficult to detect in mesenteric adipose tissue, and radioactive tracers have limits when the SLN is located near the injection site. The spatial resolution of imaging and the probe detection of radioactive tracers is limited, which is related to the acquisition method. In addition, radioactive tracers lack the ability to visualize the lymph vessels and lymph nodes in real time, which makes identification of the SLN to be removed problematic.

Near-infrared dyes may have the characteristics to solve these problems. Near-infrared dyes have a high peak spectral absorption. Wavelengths in the near-infrared range penetrate deeply into living tissue compared with visible light, so SLN staining also can be accurately assessed in mesenteric adipose tissue. The limitation of this technique until currently has been the absence of a dedicated device capable of detecting fluorescent dyes intraoperatively during laparoscopic surgery.

This study investigated the feasibility of laparoscopic SLN detection in the sigmoid by using fluorescence techniques in an acute goat model. A goat model was chosen because of the fatty mesentery, which is analogous to the human mesentery.

Methods

A laparoscopic near-infrared fluorescence imaging system (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was newly developed for this study and optimized for in vivo SLN detection with indocyanine green (ICG). The system consists of a xenon light source for excitation, filters for optimal light selection, a laparoscope, and a camera head. The lenses of the optical system are specially coated to establish near-infrared light transparency. Switches positioned at the camera head can be used to change the filters, so the system is both white light and near-infrared compatible. All procedures were recorded.

Six mature female Dutch milk goats (63–90 kg) included in a spinal fusion trial were used for the current study. All the animals were killed immediately after the procedure, and autopsy was performed. For ICG injection, a long needle was used in the four cases of percutaneous injection, whereas an R-scope (Olympus Corp.) was used in the two colonoscopy procedures.

Surgical technique

The operative procedure and animal care were performed in compliance with the regulations of the Dutch legislation for animal research, and the study protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam.

Premedication by intramuscular injection comprising 1.5 mg of atropine and 900 mg of ketamine was administered 20 min before surgery, whereas induction was achieved with intravenous etomidaat 10 to 20 mg, with adjustment guided by effect. One bolus injection of 250 μg fentanyl was administered intravenously (IV) and 15 mg midozolam was administered IV and repeated as needed. Anesthesia then was maintained with 1.5–2% isoflurane after insertion of an endotracheal tube. Breathing support was adjusted to a pressure of 0/15 to 0/20 cm H2O, a volume of ±8 to 10 ml/kg, a frequency of 14–18 breaths/min, and a carbon dioxide level of 4.0–4.5%.

Surgery was performed with the animals under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. The goats were placed in a right lateral decubitus position, and the abdominal area of the left site was shaved. Three trocars were used. Percutaneously, a urine catheter was placed into the stomach rumen to get rid of the gas produced by the fermentation going on in the rumen.

The sigmoid colon and mesocolon were exposed and studied. During the first two experiments, 25 mg of ICG (ICG-PULSION, Pulsion Medical Systems AG, Munchen, Germany) diluted in 5 ml of 0.9% NaCl was used. We injected, respectively, 5.0 and 2.5 ml of solution through the skin into the wall of the sigmoid using a long needle. During the following two experiments, the sigmoid was fixed to the abdominal wall using three stitches, positioning the mesocolon in sight. In these two experiments, 2.5 mg of ICG in 1 ml of 0.9% NaCl containing 2% of human serum albumin (HSA) (Cealb, Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) was injected subserosally in the wall of the viscera using the long needle transcutaneously.

For the subsequent two experiments, we used an R-scope (Olympus Corp.) inserted per ano into the colon and maneuvered such that the tip with its working channels was positioned at the apex of the exposed sigmoid loop. Under direct vision (both intraluminally and intraperitoneally), 2.5 mg of ICG in 1 ml of 0.9% NaCl/2% HSA was injected submucosally. Before and after the administration of ICG, 1 ml of NaCl was injected. The first injection of NaCl was used as a control for positioning the needle, and the second injection of NaCl was considered to be helpful against leakage of ICG into the lumen. In all the experiments, the mesentery was observed with both normal and near-infrared vision for visualizing the efferent lymph vessels and, subsequently, lymph node dye uptake.

Results

In all the experiments, the efferent draining lymph vessels were visualized by their bright fluorescence immediately after the ICG injection. We did not see any autofluorescence of the intraabdominal structures. There was a high signal-to-noise ratio, making it easy to detect ICG in the abdominal cavity.

During the first two experiments, no lymph nodes were detected. There was some difficulty to reach the radix and obtain a clear vision of the mesocolon. In both cases, a handport was made to assist during the search for lymph nodes. In addition, some dye spilled into the abdominal cavity. Due to the spillage, the whole abdominal cavity eventually took on a bright fluorescent appearance, especially where the folds of the colon were positioned, and the procedures therefore were adapted (see “Methods” section). Despite the spillage, the lymph vessels were easily detected.

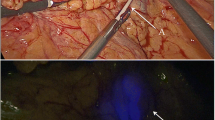

During the following two experiments, we were able to identify one sentinel node in both cases 12 and 8 min after injection. We could follow the fluorescent vessels, which ended in a bright fluorescent spot in the mesentery (Fig. 1). The sentinel node was not seen in ordinary white light mode, but could be detected easily using the near-infrared feature of the scope (Fig. 2). When the peritoneum and the mesenterial fatty tissue were opened, the fluorescent spots became even more bright (Fig. 3), and the lymph nodes then also could be identified by normal light.

Subsequent to the autopsy 2 h after injection, the sigmoid was examined in a laparoscopic training box. In both specimens, the sentinel nodes could be detected ex vivo. In one case, a second echelon lymph node was seen that had not been observed during the in vivo experiment. This discolored lymph node was located deep at the base of the radix mesentery. All the fluorescent lymph nodes were harvested.

We also compared the fluorescent SLNs with other regional lymph nodes using the near-infrared features of the scope. No fluorescent signal was detected in any of the regional lymph nodes. Ex vivo experiments showed a penetration depth of at least 7 mm through fat tissue.

During our final two experiments, ICG was injected submucosally by colonoscopy. The ICG formulation was similar to that of our third and fourth experiments. In both procedures, a sentinel node became visible after 10 min (Table 1).

Discussion

In the treatment of colon cancer, SLN detection could have a future role. As a prerequisite, it should be possible to identify and harvest the SLN in an accurate, safe, fast, and reliable manner. Previous publications showed this as a point of concern [9, 10].

The methods used for SLN mapping to date face some difficulties that could influence their accuracy in identifying the SLN. As in breast cancer and melanoma, both radio- and dye-guided imaging have been used for SLN detection in patients with colon cancer. The ink-based tracers have a poor tissue contrast and tend to diffuse through the lymph nodes because of their small particle size. On the other hand, radio-guided imaging faces the problem of signal interference of the injection site if the SLN is located near the tumor. In addition, the lymph vessels and lymph nodes cannot be visualized in real time.

Near-infrared dyes may possess the characteristics needed to solve these problems. Indocyanine green, a water-soluble tricarbocyanine approved for clinical use, has a peak spectral absorption at 800–810 nm in blood plasma and blood. Wavelengths in the 800-nm range penetrate deeply into living tissue compared with visible light. This makes it possible to detect the SLN accurately in mesenteric adipose tissue. The lymphatic collection process is strongly related to particle size. Nakajima et al. [11] considered 40 nm to be the most appropriate bead size for SLN detection in rats.

In our study, when ICG was dissolved in a NaCl/2% HSA solution before administration, the dye stayed entrapped in the SLN. It seemed that ICG diluted in 0.9% NaCl without HAS was not suitable for SLN identification. However, confirmatory studies on this topic are needed. The second echelon lymph node missed in vivo but found during ex vivo evaluation was located at the radix mesentery. The presence of four subsequential stomachs and the anatomic properties of the radix of the goat colon make a proper surgical exposure extremely difficult. As another explanation, uptake of ICG in this lymph node may have occurred after the in vivo observation period.

The injection volume and concentration of ICG for optimal clinical use need to be validated in the future. One of the major challenges in using a percutaneous injection method is to avoid leakage of dye during and after injection. Once spillage occurs, the whole abdominal cavity will be contaminated. When the dye is spilled, it is very hard to wash away. The background fluorescence of the spilled material will complicate the detection of the SLN. An alternative method could be the submucosal injection during colonoscopy. When leakage occurs with this procedure, it will be in the lumen and not in the abdominal cavity. But even then, fluorescence will be seen through the colon wall.

The development of intraoperative photodetection could pave the way to perfect minimally invasive surgery. The group of Marescaux [12] successfully used the technique of natural orifice transluminal surgery (NOTES) for sentinel biopsy of the colon in six pigs. Methylene blue was used for detection of the lymph vessels and SLNs. However, as discussed earlier, this may not be the preferred dye for humans with a fatty mesentery, so such positive results are not likely to be expected in the clinical situation. In the near future, early colon cancers may be treated by local resection therapy alone with a minimally invasive surgical sentinel node procedure using fluorescent dyes [2].

New fluorescent dyes are being developed by industries all over the world. Most of them are facing toxicology studies and will not be available for clinical evaluation in the near future. But a few fluorescent dyes already are available commercially for clinical use [2]. With the development of the new near-infrared laparoscope, intraoperative visualization of these dyes has become possible. New applications can be explored by using these dyes conjugated to monoclonal antibodies. Fluorescent imaging may provide the surgeon with a tool for intraoperative detection and diagnostic methods for cancer irradiation.

Conclusions

Before clinical implementation, the sentinel node procedure for patients with colon cancer needs to be improved. The fluorescent technique seems to be a very promising new method. Intraoperative photodetection of the SLN with the use of fluorescence may overcome many limitations of current techniques. This report presents the feasibility of the SLN technique using fluorescence and a newly developed near-infrared laparoscope in a goat model. The next step is to validate this technique in a clinical trial.

References

Terwisscha Van Scheltinga SE, Den Boer FC, Pijpers R, Meyer GA, Engel AF, Silvis R, Meijer S, van der Sijp JR (2006) Sentinel node staging in colon carcinoma: value of sentinel lymph node biopsy with radiocolloid and blue staining. Scand J Gastroenterol 243(Suppl):153–157

Meijerink WJ, van der Pas MH, van der Peet DL, Cuesta MA, Meijer S (2009) New horizons in colorectal cancer surgery. Surg Endosc 23:1–3

Bilchik AJ, Trocha SD (2003) Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node analysis to optimize laparoscopic resection and staging of colorectal cancer: an update. Cancer Control 10:219–223

Bilchik AJ, Hoon DS, Saha S, Turner RR, Wiese D, DiNome M, Koyanagi K, McCarter M, Shen P, Iddings D, Chen SL, Gonzalez M, Elashoff D, Morton DL (2007) Prognostic impact of micrometastases in colon cancer: interim results of a prospective multicenter trial. Ann Surg 246:568–575

Cote RJ, Houchens DP, Hitchcock CL, Saad AD, Nines RG, Greenson JK, Schneebaum S, Arnold MW, Martin EW Jr (1996) Intraoperative detection of occult colon cancer micrometastases using 125 I-radiolabled monoclonal antibody CC49. Cancer 77:613–620

Iddings D, Ahmad A, Elashoff D, Bilchik A (2006) The prognostic effect of micrometastases in previously staged lymph node negative (N0) colorectal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 13:1386–1392

Liefers GJ, Cleton-Jansen AM, van de Velde CJ, Hermans J, van Krieken JH, Cornelisse CJ, Tollenaar RA (1998) Micrometastases and survival in stage II colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 339:223–228

Des Guetz G, Uzzan B, Nicolas P, Cucherat M, de Mestier P, Morere JF, Breau JL, Perret G (2007) Is sentinel lymph node mapping in colorectal cancer a future prognostic factor? A meta-analysis. World J Surg 31:1304–1312

Faerden AE, Sjo O, Andersen SN, Hauglann B, Nazir N, Gravedaug B, Moberg I, Svinland A, Nesbakken A, Bakka A (2008) Sentinel node mapping does not improve staging of lymph node metastasis in colonic cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 51:891–896

Lim SJ, Feig BW, Wang H, Hunt KK, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Skibber JM, Ellis V, Cleary K, Chang GJ (2008) Sentinel lymph node evaluation does not improve staging accuracy in colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 15:46–51

Nakajima M, Takeda M, Kobayashi M, Suzuki S, Ohuchi N (2005) Nano-sized fluorescent particles as new tracers for sentinel node detection: experimental model for decision of appropriate size and wavelength. Cancer Sci 96:353–356

Cahill RA, Perretta S, Leroy J, Dallemagne B, Marescaux J (2008) Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in the colonic mesentery by natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). Ann Surg Oncol 15:2677–2683

Acknowledgments

The authors thank R. J. Kroeze and M. N. Helder from the Orthopedic Department of the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam for creating the possibility of operating on their study subjects so we could optimize the use of their goats, Olympus Corp. for its technical services and development of the near-infrared device, and K. Meijer, J. Middelberg, and P. Sinnige of the animal facility at the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam for their excellent support in the performance of the animal experiments.

Disclosures

M. H. G. M. van der Pas, G. A. M. S. van Dongen, F. Cailler, A. Pèlegrin, and W. J. H. J. Meijerink have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Pas, M.H.G.M., van Dongen, G.A.M.S., Cailler, F. et al. Sentinel node procedure of the sigmoid using indocyanine green: feasibility study in a goat model. Surg Endosc 24, 2182–2187 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-0923-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-0923-3