Abstract

Oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD) is a high impact morbidity in head-and-neck cancer (HNC) patients. A wide variety of instruments are developed to screen for affective symptoms and OD. The current paper aims to systematically review and appraise the literature to obtain insight into the prevalence, strength, and causal direction of the relationship between affective symptoms and OD in HNC patients. This review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement. A systematic search of the literature was performed using PubMed, PsycINFO, Cochrane, and Embase. All available publications reporting on the relationship between affective conditions and swallowing function in HNC patients were included. Conference papers, tutorials, reviews, and studies with less than 5 patients were excluded. Fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria. The level of evidence and methodological quality were assessed using the ABC-rating scale and QualSyst critical appraisal tool. Eleven studies reported a positive relationship between affective symptoms and OD. The findings of this paper highlight the importance of affective symptom screening in dysphagic HNC patients as clinically relevant affective symptoms and OD seems to be prevalent and coincident in this population. Considering the impact of affective symptoms and OD on patients’ daily life, early detection and an integrated interdisciplinary approach are recommended. However, due to the heterogeneity of study designs, outcomes, and outcome measures, the generalization of study results is limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Swallowing is a complex neurocognitive process. It relies on accurate coordination of a variety of muscle and nerve groups aiming at efficient bolus preparation and safe and efficient bolus transfer from the oral cavity and pharynx to the esophagus [1]. Damage of upper aerodigestive tract tissue due to a head-and-neck malignancy or its oncological treatment may cause oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD) [2, 3]. The incidence of head-and-neck cancer (HNC) is rising, partly due to increasing numbers of human papilloma virus (HPV)-related oropharyngeal cancer resulting in a growing population of patients with a need for long-term healthcare [4]. OD is a high impact morbidity in head-and-neck cancer (HNC) patients with a reported prevalence of 45% [2, 5]. OD can be accompanied by severe complications such as aspiration pneumonia, sepsis, or malnutrition [3, 6]. Therefore, early screening, diagnosis, and treatment are essential to minimize the consequences of OD.

Besides affecting overall health, HNC may also affect mental health, social functioning, and employment [2]. This range of issues may have major effects on social and psychological well-being. The diagnosis and treatment of HNC itself may result in a significant burden on the patients’ psychological state because patients often find themselves in an ‘existential crisis situation’ [7]. Moreover, OD is often accompanied by anxiety, depression, reduced self-esteem, and social isolation, further amplifying the HNC-related suffering [6]. The recognition and treatment of the psychosocial burden in patients with HNC is important as distress may interfere with the ability to cope with the disease, its oncological treatment, and rehabilitation. The increasing incidence of HNC, combined with a high prevalence of psychological comorbidity in HNC patients [8], emphasizes the importance of an interdisciplinary approach including mental health care.

A wide variety of instruments are developed to screen for affective (anxiety and depression) symptoms and swallowing dysfunction. Screening tools are used for early identification of individuals at potentially high risk for a specific disorder. A screening tool such as the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) is useful to identify clinically relevant anxiety and depressive symptoms [9]. For further identification of the nature and severity of a psychological disorder, a neuropsychological diagnostic workup is required. Regarding swallowing function, a screening tool such as the water swallow test (WST) is a quick and non-invasive method to identify patients at risk for unsafe swallowing [10]. After positive screening for OD, a clinical examination by a speech and language pathologist and/or instrumental swallowing assessment are recommended. In the literature, fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) and videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) are considered the golden standard examinations to assess the swallowing function [11]. Besides clinician-reported outcome (CRO), self-evaluation is covered by patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaires. These questionnaires can roughly be divided into two different concepts: health-related quality of life (HRQoL) versus functional health status (FHS) questionnaires. FHS is often defined as one’s ability to perform daily activities required to meet basic needs, fulfill usual roles, and maintain their health and well-being [12]. HRQoL is a multi-dimensional concept that includes domains related to physical, mental, emotional, and social functioning [13]. HRQoL focuses on the impact of health status on quality of life [11, 14]. The concepts of HRQoL and FHS are often mixed, making it difficult to distinguish between tools that measure disease-related-QoL and functioning.

The aim of the present study is to systematically review and appraise the literature to obtain insight into the prevalence, strength, and causal direction of the relationship between OD and clinically relevant affective symptoms in HNC patients. A better understanding of this relationship will contribute to a better interdisciplinary approach to both problems (OD and affective symptoms) that can adversely affect each other during oncological treatment and rehabilitation.

Methods

Selection Process

The search strategy was developed using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) format as described in Table 1 [15]. To ensure an accurate and comprehensive capture of the study aims, a systematic literature search was carried out together with a university librarian, using four electronical databases (PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, and PsycINFO) on January 3, 2022. The databases were searched from January 1980 to December 2021.

The methodology and reporting of this review were carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [16]. Medical subject headings as well as free text words with truncation were used. Full search strategies specific to each database are described in Table 2. Two blinded independent reviewers included abstracts if the following criteria were met: (1) reporting on affective conditions (anxiety, depression, or emotional status), (2) reporting on swallowing function, (3) reporting on affective symptoms in relation to swallowing function, (4) in a population of patients with mucosal squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, (5) published in English, Dutch, German, Portuguese, Spanish, French, and (6) full-text retrievable. Conference papers, tutorials, reviews, duplicates, and studies with less than five patients were excluded. The same blinded independent reviewers screened full-text articles according to the same abstract inclusion criteria. The reference lists of the selected articles were hand screened for additional literature. The level of agreement between the two reviewers for eligibility after full-text screening was determined using percentage of agreement and Cohen’s kappa (κ). Discrepancies in article selection were resolved by consensus discussion.

Level of Evidence and Critical Appraisal

The level of evidence of all included studies was assessed using the ABC-rating scale [17]. In this scale, level A refers to high‐quality randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis; level B refers to nonrandomized clinical trials, nonquantitative systematic reviews, and clinical cohort studies, and level C refers to consensus viewpoints and expert opinions.

Subsequently, the reviewers independently appraised the included articles for methodological quality according to the QualSyst critical appraisal tool [18]. The QualSyst tool is developed for the quality assessment of both qualitative and quantitative studies using any study design. The QualSyst tool for standard quality assessment of quantitative studies is a validated checklist that is made up of 14 criteria to be assessed including research questions and objectives, study design, subject and comparison group selection and characteristics, interventional allocation, definitions of outcomes, sample size, analytic methods, confounding, reported results, and conclusions. The scores of each item range from 0 to 2 with a maximum total QualSyst score being 28. A summary score can be obtained by dividing the total score by the total possible score [.e., 28 − (number of not applicable items × 2)]. According to the QualSyst tool, the methodological quality of the articles can be classified as limited < 0.50, adequate 0.50–0.70, good 0.70–0.80, and strong > 0.80 [19]. The level of agreement between the two reviewers for the ABC-rating scale and the QualSyst critical appraisal tool was obtained using percentage of agreement.

Data Extraction

Both independent reviewers extracted relevant data into summary tables (Tables 3 and 4). Extracted data included sample size, study population (etiology, age, and sex), method of OD and affective symptom assessment, timing of assessment, and study results according to the authors. Descriptive summaries were generated, including the exploration of relationships in the data. Finally, critical reflection of this review process was described in the discussion section of this paper. Radiographic procedure that provides a dynamic view of oral, pharyngeal, and upper esophageal function during swallowing.

Results

The systematic searches across all databases yielded a total of 139 abstracts after duplicate references were removed. Of these, 86 abstracts were removed based on the exclusion criteria. The full-text of the remaining 53 abstracts was reviewed. Two articles were identified after hand searching the reference lists of the included studies. Finally, 15 articles were included in this systematic review. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the search process (Fig. 1).

The two reviewers had 78% agreement (κ = 0.55) on the selection based on title and abstract screening. Articles that were selected by just one of the reviewers were subsequently screened using the full-text. At the full-text review stage, the two reviewers had 84% agreement (κ = 0.63) on their ratings. The two reviewers had 100% agreement on the ABC-rating scale and 93.3% on the QualSyst ratings. Disagreements were discussed and resolved in consensus.

Methodological Quality of Included Studies

All studies met the criteria of level B according to the ABC-rating scale (eight cross-sectional studies, six clinical cohort studies, and one case–control study) [17]. The methodological quality of the studies based on the QualSyst ratings ranged from adequate (0.68) to strong (0.96). Seven articles were ranked as strong [20,21,22,23,24,25,26], four as good [27,28,29,30], and four as adequate [25, 31,32,33]. The level of evidence and methodological quality of the 15 articles are presented in Table 4.

Swallowing Function and Affective Symptoms

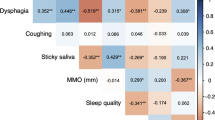

Swallowing function was investigated by a range of CRO tools such as OD screening tools (WST) and CRO tools such as VFSS and FEES [10, 34, 35]. Visuoperceptual ordinal variables on swallowing safety and efficiency, the dysphagia outcomes and severity scale (DOSS), the swallowing performance scale (SPS), and the penetration–aspiration scale (PAS) were the outcome measures used for VFSS and FEES [36,37,38]. Patients’ perception of the swallowing function was evaluated using the following PRO HRQoL questionnaires: the global, functional, and physical subscales of the MD Anderson dysphagia inventory (MDADI), the swallowing domain of the University of Washington quality of life (UW-QOL), the swallowing domain of the Dische morbidity recording scheme, and the swallowing domain of the European organization for research and treatment for cancer quality of life questionnaire head and neck module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) [39,40,41,42].

Affective symptoms were measured using CRO or PRO questionnaires. The majority of the questionnaires was specifically developed to measure depression or anxiety symptoms such as the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), hospital Beck depression inventory fast screen (BDI-FS), depression anxiety stress score (DASS), Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS), and the Zung self-rating depression scale (SDS) [9, 43,44,45,46]. Questionnaires with a domain reporting on patients’ emotional status, such as the mood and anxiety domains of the UW-QOL (version 4) and the emotional domain of the MDADI, were also included in this systematic review [47]. The most frequently used PRO measure was the HADS followed by the MDADI and the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 questionnaires.

FHS was measured using the performance status scale for head-&-neck cancer patients (PSS-HN), functional assessment of cancer therapy-general, functional assessment of cancer therapy-head and neck questionnaires (FACT-G and FACT-H&N) [48,49,50]. An overview of the characteristics and validation of the tools used to screen or measure swallowing function and affective symptoms in the included articles is presented in Table 3.

Table 4 summarizes the data retrieved from the included articles regarding sample size, oncological treatment modalities, measurements tools, outcome measures, and the reported relationship between swallowing function and affective symptoms or emotional status. The sample size of the included studies ranged from 9 to 110. The mean age of the patients in the included studies ranged from 27 to 83 and most of the included patients were male. Eleven studies included a heterogeneous mix of head and neck tumor locations, one study only included patients with oral cavity cancer, another study only included patients with oropharyngeal cancer, and two studies only included patients who had undergone a total laryngectomy. Surgery was the most frequently applied oncological treatment, and in some studies, this treatment modality was followed by adjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy. In the majority of the studies, swallowing function and affective symptoms were evaluated after the oncological treatment was ended (mean duration of time interval: 38 months (range 1–63 months).

In the included studies, the prevalence of OD ranged from 16 to 100%. The reported prevalence for clinically relevant affective symptoms ranged from 12 to 54%. A positive relationship between OD and affective symptoms or emotional status was described in most of the studies [20, 22, 24,25,26,27,28, 30,31,32, 51]. Four studies found a non-significant or negative relationship between swallowing function and affective symptoms or emotional status [21, 23, 29, 33]

Discussion

The initial purpose of the present study was to systematically review and appraise the literature on the prevalence of affective symptoms and to identify the strength and direction of the relationship between OD and clinically relevant affective symptoms in HNC patients. A better understanding of this relationship will contribute to a better interdisciplinary approach to both problems (OD and affective symptoms) that can adversely affect each other during oncological treatment and rehabilitation. In general, OD and affective symptoms were related to each other as described below. However, the results of this systematic review have not been able to adequately answer the question on the strength and direction of this relationship.

In total, 15 articles were included. The methodological quality of the included studies ranged from adequate (0.86) to strong (0.96). Due to the heterogeneity of study designs, terminology, outcomes, and outcome measures used, a meta-analysis could not be conducted.

A positive relationship between OD and affective symptoms or emotional status was described in the majority of the studies [20, 22, 24,25,26,27,28, 30,31,32, 51]. Nguyen et al. reported that HNC patients experience anxiety and depression related to their OD severity which can be explained by the functional impairment and disfigurement resulting from HNC and its treatment [30]. Eating and drinking is an important part of social interaction, but dysphagic HNC patients often experience eating difficulties in public and home environment [23]. In some cases, this may lead to exclusion of invitations or to patients declining to eat out. Therefore, patients may become socially isolated leading to symptoms of anxiety and depression. Maclean et al. and Zhang et al. described that an improvement in swallowing function may reduce the severity of affective symptoms in HNC patients [28, 30]. On the other hand, affective symptoms can cause physical complaints such as dry mouth which may enhance swallowing impairment [45]. Furthermore, affective symptoms can negatively affect motivation and consequently compliance during cancer rehabilitation, resulting in a poor functional outcome [50]. Bozec et al. described that depressive symptom scores are independent predictors of poorer swallowing function in HNC patients, highlighting the fact that swallowing function is highly dependent on psychological, emotional, and social conditions in addition to tumor or treatment characteristics [26]. In addition, the patient’s psychological baseline should be taken into account as affective symptoms may already be present prior to the HNC diagnosis [26].

Although a positive relationship between OD and affective symptoms has been described in the majority of the included studies, other studies found a non-significant or negative relationship between swallowing function versus anxiety, depression, or emotional status [21, 23, 29, 33]. The reasons for these divergent findings can be multiple. For example, the timing of assessment of OD and affective symptoms varies widely between these studies. The moment of measurement plays an important role in the outcome of swallowing-, physical-, and emotional functioning. The longitudinal study of Hammerlid et al. reported that patients may develop coping skills or undergo changes in the experience of the disease and in their expectations of health over time resulting in improved symptom scores [51]. These findings justify the recommendation to systematically screen for affective symptoms and swallowing disorders at baseline (before oncological treatment) and during the oncological follow-up.

A variety of tools measuring swallowing function and affective symptoms were used in the included studies. These different tools vary in use and purpose (screening versus diagnostic) and the interpretation and clinical relevance of the outcome measures should be taken into account. Multiple PRO HRQoL questionnaires were used to measure patients’ perception of the swallowing function based on the multi-dimensional concept of HRQoL including domains related to physical, mental, emotional, and social functioning. However, only one study included PRO FHS questionnaires to determine the impact of OD on the ability to perform daily activities [29]. In a cross-sectional study, Campbell et al. aimed to determine associations between instrumental assessment (VFSS), PRO HRQoL measurement (UW-QOL), and FHS measurements (FACT-G, FACT-H&N and PSS-HN) in HNC survivors, 5 years post-treatment [29]. Patients presenting aspiration of the bolus into the airway scored significantly lower on the UW-QOL swallowing domain, FACT-H&N additional concerns, and PSS-HN ‘normalcy of diet’ domain, compared to non-aspirators. Aspiration was not associated with PSS-HN ‘willingness to eat in public’ domain nor with any of the FACT-G well-being scales. So, despite unsafe swallowing (VFSS) and poor swallowing-related HRQoL (UW-QOL), aspiration of the bolus into the airway does not seem to impact everyday activities and fulfilling usual roles.

It is not uncommon to find a discrepancy between the results of PRO and CRO measures [52]. Airoldi et al. reported on a discrepancy between a self-reported prevalence of depressive symptoms of 30% measured using the HADS versus a clinician-reported prevalence of 44.4% measured by the MADRS in a population of patients following treatment for oral cancer [27]. The authors concluded that this discrepancy might be related to an inadequate self-awareness of HNC patients concerning illness-related psychological distress. Furthermore, according to the authors, a higher prevalence of having a vulnerable socioeconomic status, addictive behavior, and anosognosia can play a role in limited self-awareness in this patient population [27]. In addition, Florie et al. reported on the very few statistically significant mean differences of MDADI subscale scores between the ordinal scale levels of several FEES variables in a heterogenous population of HNC patients following cancer treatment. This study also described a weak relationship between the severity of OD and PRO OD-specific HRQoL. The authors concluded that adaptive changes in swallowing function, radiation neuropathy with a decreased oropharyngeal sensibility, and the patients’ noncomplaining nature and lack of initiative may affect the perception (underestimation) of their swallowing difficulties. That perception or underestimation, in turn, may determine their score on the MDADI questionnaire [21]. The MDADI was developed to measure the influence of OD on the patients’ HRQoL. Nevertheless, it still remains unclear if the MDADI can be used as an indicator for the severity of OD [21]. Although these PRO and CRO measures do not correlate well, it remains important to realize the existence of these different dimensions of OD as well as their application and relevance in both scientific research and daily clinical practice.

Non-validated measurement tools were used in eleven of the included studies. The use of high-quality measurement tools based on robust psychometric properties such as validity and reliability is strongly recommended and essential to accurately estimate the prevalence of affective symptoms and OD [53].

Although no meta-analytic conclusions can be drawn from the included articles, OD and affective symptoms often appear to be coincidental in HNC patients. The included studies reported a prevalence of OD ranging from 16 to 100% and a prevalence of clinically relevant affective symptoms ranging from 12 to 54%. This wide variation in the prevalence of OD and clinically relevant affective symptoms in the different studies may be due to several reasons: different study designs with various HNC patient samples (variation in age, tumor location, tumor stage, oncological treatment, etc.), the use of different and/or non-validated measuring instruments for OD and affective symptoms in HNC patients, different timing of measurement, etc.

Seven studies reported the effects of tumor location, tumor stage, and/or oncological treatment modality on swallowing, and affective symptoms [23, 26, 28,29,30,31,32, 51]. Depending on the tumor location, swallowing function may be affected in different ways. For instance, in the literature, a higher incidence of aspiration before the start of the oncological treatment is reported in patients with laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer [54]. However, the included studies of the present review did not report on the relationship between tumor location and OD severity nor on the relationship between tumor location and clinically relevant affective symptoms. A significant relationship between tumor stage versus OD and depressive symptoms was reported [26, 29, 30]. An advanced tumor stage can cause more severe OD and functional impairment due to a greater extent of damage to essential structures of the upper aerodigestive tract. However, this relationship was established after oncological treatment, so most likely the type and number of oncological treatment modalities play a role in this relationship. Advanced primary site disease often necessitates aggressive multimodality treatment, which puts patients at greater risk of long-term disability as a result of surgical and adjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy induced functional loss [30]. (Chemo)radiotherapy may induce mucositis, stomatitis, hyposalivation, trismus, soft tissue necrosis, fibrosis, and osteoradionecrosis of the mandible [27]. The effect of surgery on swallowing function and affective symptoms should also be considered as OD, and affective symptoms seem to be related to the location and extent of the resection. A significant association between the extent of tongue(base) resection versus OD and depressive symptoms was reported [26, 31]. However, six studies did not find any effect of tumor location, tumor stage, and type of oncological treatment modality on the prevalence of affective symptoms and OD showing that this relationship is not yet well understood [23, 25, 28, 32, 33, 51].

All included studies applied patient-reported questionnaires on OD and affective symptoms. However, only few studies screened or assessed the level of cognition of the included patients [21,22,23]. When using PRO tools, it is necessary to screen or estimate the level of cognition prior to completing a self-report questionnaire to guarantee that patients are able to understand and answer the questions accordingly. Cognitive impairment may complicate recall-based assessment with questionnaires resulting in recall bias. Besides cognition, alcohol consumption should also be reported when evaluating affective symptoms. Prolonged alcohol use is often seen in HNC patients and known to cause structural changes in the brain as well as cognitive deficits [55]. Four articles reported on a significant association between alcohol abuse and long-term psychological distress, resulting in a vicious circle in which these phenomena reinforce each other [27, 28, 30, 33]. This highlights the importance to support HNC patients with an active addiction. Finally, although the use of psychotropic drugs is likely to influence the severity of affective symptoms, only two studies reported on the use of psychotropic drugs [22, 23].

Limitations and Risk of Bias

This systematic review has some limitations. The systematic search generated a low number of articles on affective symptoms and OD in HNC patients. Reasons for this low number may be related to the inconsistent terminology used in this research topic. The lack of randomized controlled trials and pre- and post-treatment data studies may limit the strength of the findings. All studies had methodological limitations (e.g., lack of details provided regarding selection criteria; small sample sizes; limited information on methods, incomplete information about measurement tools and procedures; no information about test result interpretation). The heterogeneity of the included studies is likely to have contributed to the overall variation in reported frequencies of OD and affective symptoms and precluded eligibility to pool data across studies.

Conclusion

This study shows that screening for affective symptoms in dysphagic HNC patients should be considered as affective symptoms and OD seems to be prevalent and coincident in this population. The strength and direction of the relationship between affective symptoms and OD still remain unclear. Considering the impact of affective symptoms and OD on patients’ daily life, early detection and an integrated interdisciplinary approach are recommended. Future studies should use validated measurement tools, bigger sample sizes, and study designs that lead to high-quality evidence.

References

Huckabee SKDM, et al. Dysphagia following stroke. 3rd ed. San Diego: Plural Publishing; 2019. p. 35–6.

Manikantan K, Khode S, Sayed SI, Roe J, Nutting CM, Rhys-Evans P, Harrington KJ, Kazi R. Dysphagia in head and neck cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:724–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.08.008.

Dysphagia Section OCSG, Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/International Society of Oral Oncology (ISOO), Raber-Durlacher JE, Brennan MT, et al. Swallowing dysfunction in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(3):433–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1342-2.

Simcock R, Simo R. Follow-up and survivorship in head and neck cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2016;28:451–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2016.03.004.

Hutcheson KA, Nurgalieva Z, Zhao H, Gunn GB, Giordano SH, Bhayani MK, Lewin JS, Lewis CM. Two-year prevalence of dysphagia and related outcomes in head and neck cancer survivors: an updated SEER-medicare analysis. Head Neck. 2019;41:479–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25412.

Verdonschot R, Baijens LWJ, Vanbelle S, van de Kolk I, Kremer B, Leue C. Affective symptoms in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2017;97:102–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.04.006.

Moore KA, Ford PJ, Farah CS. Support needs and quality of life in oral cancer: a systematic review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2014;12:36–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/idh.12051.

Baijens LWJ, Walshe M, Aaltonen LM, Arens C, Cordier R, Cras P, Crevier-Buchman L, Curtis C, Golusinski W, Govender R, Eriksen JG, Hansen K, Heathcote K, Hess MM, Hosal S, Klussmann JP, Leemans CR, MacCarthy D, Manduchi B, Marie JP, Nouraei R, Parkes C, Pflug C, Pilz W, Regan J, Rommel N, Schindler A, Schols A, Speyer R, Succo G, Wessel I, Willemsen ACH, Yilmaz T, Clave P. European white paper: oropharyngeal dysphagia in head and neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278:577–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06507-5.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

Suiter DM, Leder SB. Clinical utility of the 3-ounce water swallow test. Dysphagia. 2008;23:244–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-007-9127-y.

Speyer R. Oropharyngeal dysphagia: screening and assessment. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2013;46:989–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2013.08.004.

Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273:59–65.

Ferrans CE, Zerwic JJ, Wilbur JE, Larson JL. Conceptual model of health-related quality of life. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2005;37:336–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00058.x.

Jones E, Speyer R, Kertscher B, Denman D, Swan K, Cordier R. Health-related quality of life and oropharyngeal dysphagia: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2018;33:141–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9844-9.

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-7-16.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hrobjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Siwek J, Gourlay M, Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. How to write an evidence-based clinical review article. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(2):251–8.

Kmet LM LR, Cook LS (2004) Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR)

Lee L, Packer TL, Tang SH, Girdler S. Self-management education programs for age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review. Australas J Ageing. 2008;27:170–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00298.x.

Chan JY, Lua LL, Starmer HH, Sun DQ, Rosenblatt ES, Gourin CG. The relationship between depressive symptoms and initial quality of life and function in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1212–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.21788.

Florie M, Baijens L, Kremer B, Kross K, Lacko M, Verhees F, Winkens B. Relationship between swallow-specific quality of life and fiber-optic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing findings in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1848-1856. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24333.

Kemps GJF, Krebbers I, Pilz W, Vanbelle S, Baijens LWJ. Affective symptoms and swallow-specific quality of life in total laryngectomy patients. Head Neck. 2020;42:3179–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26365.

Krebbers I, Simon SR, Pilz W, Kremer B, Winkens B, Baijens LWJ. Patients with head-and-neck cancer: dysphagia and affective symptoms. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1159/000508367.

Maclean J, Cotton S, Perry A. Dysphagia following a total laryngectomy: the effect on quality of life, functioning, and psychological well-being. Dysphagia. 2009;24:314–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-009-9209-0.

Cnossen IC, de Bree R, Rinkel RN, Eerenstein SE, Rietveld DH, Doornaert P, Buter J, Langendijk JA, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. Computerized monitoring of patient-reported speech and swallowing problems in head and neck cancer patients in clinical practice. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2925–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1422-y.

Zhang L, Huang Z, Wu H, Chen W, Huang Z. Effect of swallowing training on dysphagia and depression in postoperative tongue cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18:626–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2014.06.003.

Airoldi M, Garzaro M, Raimondo L, Pecorari G, Giordano C, Varetto A, Caldera P, Torta R. Functional and psychological evaluation after flap reconstruction plus radiotherapy in oral cancer. Head Neck. 2011;33:458–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.21471.

Bozec A, Demez P, Gal J, Chamorey E, Louis MY, Blanchard D, De Raucourt D, Merol JC, Brenet E, Dassonville O, Poissonnet G, Santini J, Peyrade F, Benezery K, Lesnik M, Berta E, Ransy P, Babin E. Long-term quality of life and psycho-social outcomes after oropharyngeal cancer surgery and radial forearm free-flap reconstruction: a GETTEC prospective multicentric study. Surg Oncol. 2018;27:23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2017.11.005.

Campbell BH, Spinelli K, Marbella AM, Myers KB, Kuhn JC, Layde PM. Aspiration, weight loss, and quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:1100–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.130.9.1100.

Lin BM, Starmer HM, Gourin CG. The relationship between depressive symptoms, quality of life, and swallowing function in head and neck cancer patients 1 year after definitive therapy. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1518–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.23312.

Hartl DM, Dauchy S, Escande C, Bretagne E, Janot F, Kolb F. Quality of life after free-flap tongue reconstruction. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:550–4. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215108003629.

Nguyen NP, Frank C, Moltz CC, Vos P, Smith HJ, Karlsson U, Dutta S, Midyett A, Barloon J, Sallah S. Impact of dysphagia on quality of life after treatment of head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:772–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.06.017.

Zwahlen RA, Dannemann C, Graetz KW, Studer G, Zwahlen D, Moergeli H, Drabe N, Buchi S, Jenewein J. Quality of life and psychiatric morbidity in patients successfully treated for oral cavity squamous cell cancer and their wives. J Oral Maxil Surg. 2008;66:1125–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2007.09.003.

Logemann JA. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. 2nd ed. Austin: PRO-ED; 1997.

Langmore S. Endoscopic evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. New York: Thieme; 2000. p. 1–6.

O’Neil KH, Purdy M, Falk J, Gallo L. The dysphagia outcome and severity scale. Dysphagia. 1999;14:139–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00009595.

Karnell MPME. A data base information storage and reporting system for videofluorographic oropharyngeal motility (OPM) swallowing evaluations. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1994;3:54–60.

Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996;11:93–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00417897.

Chen AY, Frankowski R, Bishop-Leone J, Hebert T, Leyk S, Lewin J, Goepfert H. The development and validation of a dysphagia-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer: the M. D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:870–6.

Weymuller EA Jr, Alsarraf R, Yueh B, Deleyiannis FW, Coltrera MD. Analysis of the performance characteristics of the University of Washington Quality of Life instrument and its modification (UW-QOL-R). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:489–93. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.127.5.489.

Cooper JS, Fu K, Marks J, Silverman S. Late effects of radiation therapy in the head and neck region. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1141–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-3016(94)00421-G.

Bjordal K, Hammerlid E, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, de Graeff A, Boysen M, Evensen JF, Biorklund A, de Leeuw JR, Fayers PM, Jannert M, Westin T, Kaasa S. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patients: validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-H&N35. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1008–19. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1008.

Lovibond SHLP. Manual for the depression, anxiety, stress scales. 2nd ed. Sydney: Psychological Foundation; 1995.

Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.134.4.382.

Kliem S, Mossle T, Zenger M, Brahler E. Reliability and validity of the beck depression inventory-fast screen for medical patients in the general German population. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:236–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.024.

Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008.

Rogers SN, Gwanne S, Lowe D, Humphris G, Yueh B, Weymuller EA Jr. The addition of mood and anxiety domains to the University of Washington quality of life scale. Head Neck. 2002;24:521–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.10106.

List MA, Ritter-Sterr C, Lansky SB. A performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer. 1990;66:564–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19900801)66:3%3c564::aid-cncr2820660326%3e3.0.co;2-d.

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570.

List MA, D’Antonio LL, Cella DF, Siston A, Mumby P, Haraf D, Vokes E. The performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients and the functional assessment of cancer therapy-head and neck scale. A study of utility and validity. Cancer. 1996;77:2294–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11%3c2294::AID-CNCR17%3e3.0.CO;2-S.

Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Eerenstein SE, Van der Linden MH, Kuik DJ, de Bree R, ReneLeemans C. Distress in spouses and patients after treatment for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(2):238–41.

van Hooren MRA, Vos R, Florie M, Pilz W, Kremer B, Baijens LWJ. Swallowing Assessment in Parkinson’s disease: patient and investigator reported outcome measures are not aligned. Dysphagia. 2021;36:864–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-020-10201-3.

Kimberlin CL, Winterstein AG. Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:2276–84. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp070364.

Starmer H, Gourin C, Lua LL, Burkhead L. Pretreatment swallowing assessment in head and neck cancer patients. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1208–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.21800.

McCaffrey JC, Weitzner M, Kamboukas D, Haselhuhn G, Lamonde L, Booth-Jones M. Alcoholism, depression, and abnormal cognition in head and neck cancer: a pilot study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:92–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2006.06.1275.

Pilz W, Vanbelle S, Kremer B, van Hooren MR, van Becelaere T, Roodenburg N, Baijens LW. Observers’ agreement on measurements in fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. Dysphagia. 2016;31:180–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-015-9673-7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krebbers, I., Pilz, W., Vanbelle, S. et al. Affective Symptoms and Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Head-and-Neck Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia 38, 127–144 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-022-10484-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-022-10484-8