Abstract

This study aimed to critically review pediatric swallowing assessment data to determine the future need for standardized procedures. A retrospective analysis of 152 swallowing examinations in 128 children aged 21 days to 18 years was performed. The children were presented at a university dysphagia center between January 2015 and June 2020 for flexible-endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES). Descriptive analysis was conducted for the sample, swallowing pathologies, diagnosis, and missing values. Using binary logistic regression, the relationship between dysphagia and underlying diseases was investigated. The largest group with a common diagnosis in the cohort were children with genetic syndromes (n = 43). Sixty-nine children were diagnosed with dysphagia and 59 without dysphagia. The non-dysphagic group included 15 patients with a behavioral feeding disorder. The presence of an underlying disease significantly increased the chance of a swallowing problem (OR 13.08, 95% CI 3.66 to 46.65, p = .00). In particular, the categories genetic syndrome (OR 2.60, 95% CI 1.15 to 5.88) and neurologic disorder (OR 4.23, 95% CI 1.31 to 13.69) were associated with higher odds for dysphagia. All pediatric FEES were performed without complications, with a completion rate of 96.7%, and with a broad variability of implementation. Several charts lacked information concerning swallowing pathologies, though. Generally, a more standardized protocol and documentation for pediatric FEES is needed to enable better comparability of studies on epidemiology, assessment, and treatment outcomes in future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite an increasing prevalence of dysphagia [1,2,3] and a high demand for interdisciplinary diagnostics and therapy, pediatric patients still are underrepresented in dysphagia research. A further increase might be expected due to the higher chance of survival of very premature children [4] and of children with complex diseases who are at risk of dysphagia [5]. Besides, there is a lack of standardized diagnostic procedures both in clinical practice and in research [6]. No internationally accepted definition of pediatric swallowing disorders is available to date; most published studies are not based on the same definition or do not differentiate between behavioral feeding disorders and dysphagia [7]. This causes difficulties in comparison and replication, e.g., of epidemiological surveys [1, 8], and limitation of the informative content.

Swallowing disorders in children have a significant impact on health, cognitive development [9], and quality of life of the entire family [10, 11]. Due to these burdening consequences, the use of well-evaluated diagnostic instruments and clear criteria for early detection is mandatory to establish early and appropriate therapy [12,13,14].

So far, clinical swallowing evaluation (CSE) on its own cannot validly predict aspiration [12, 15]. Besides, currently, there are no valid clinical markers or predictors for oropharyngeal dysphagia with aspiration in children [16,17,18,19,20].

Descriptions of pediatric FEES routines were recently published by Miller, Schroeder, and Langmore [21] and Miller and Willging [22]. Modified procedures especially for breastfeeding [23, 24] or for the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) [25, 26] have been tried and found to be safe. Objective methods for a transfer into a score such as the penetration-aspiration scale (PAS) according to Rosenbek [27] have not yet been validated for pediatric FEES, but are frequently in use.

This study aimed to systematically evaluate the pediatric swallowing diagnostics carried out at our university dysphagia center. The underlying hypothesis was that the lack of a standard protocol leads to gaps in documentation and thus poor comparability of findings. The results of this study are intended to serve as the fundament for subsequent development of standard pediatric FEES protocol and documentation.

Methods

In this study, the electronic medical records of 152 swallowing examinations of 128 children aged 21 days to 18 years performed at a university dysphagia center between January 2015 and June 2020 were analyzed (see Table 1 and Fig. 1 for age distribution).

Swallowing Examination

FEES was performed by experienced specialists in phoniatrics and otorhinolaryngology, using a 2.6 mm diameter high-definition rhino-laryngo-videoscope (ENF-V3, Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan), and accompanied by a speech-language pathologist (SLP) and a nurse. Age-appropriate dosage of nasal decongestant (Otriven, Xylometazoline hydrochloride: 0–2 years 0.25 mg; 2–6 years 0.5 mg; > 6 years: 1.0 mg) and topical viscous lidocaine (Xylocaine Gel 2%, Aspen Germany, 0.1 ml) were applied routinely. Nasogastric tubes were usually not removed, and pulse oximetry monitoring was only used for medically complex children. The young patients sat upright on the caregiver's lap, if possible, with the nurse stabilizing their head until the endoscope was passed through the nasal airway. Developmentally appropriate test boluses of different consistencies (e.g., fluid, thickened fluid, nectar thick or honey-thick, puree, solid) were administered by spoon, cup, bottle, or syringe in non-standardized bolus sizes. Mainly the children's preferred food was brought from home and lightly dyed with green food color ("Condi Light Green" E104 Quinoline Yellow + E132 Indigotine I, Schreiber-Essenzen GmbH & Co KG, Barsbüttel, Germany). Fluids or thin puree were thickened using modified corn starch (Thick & Easy, Fresenius Kabi, Germany). The procedure of FEES was carried out according to the FEES protocol of Langmore [28,29,30], albeit in non-standard modifications. The implementation depended on the examiner and the patient. Occasionally, only one consistency could be examined, and in some rare cases, the endoscopy was performed only immediately after oral intake of the bolus to check for residues and aspiration. The supplementary videos 1 to 4 give an impression of the examinations carried out on children of different ages and diagnoses.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistic version 27 (IBM, USA). Descriptive analysis was conducted for the number of cases, the sample profile (age, gender, underlying disease, tube feeding, ventilation), functional swallowing pathologies (aspiration, laryngeal penetration, spillage, residue, delayed swallowing reflex, reduced laryngopharyngeal sensation), and the resulting description of the diagnosis. Binary logistic regression (forward, stepwise) was calculated for dichotomous variables (disease/no disease; dysphagia/no dysphagia). The level of significance was 0.05.

Results

Subject Characteristics

As summarized in Table 1, 45.3% of the 128 children were female and 54.7% male. There was a large number of children with genetic syndromes (see Table 2), including children with rare diseases such as Pompe disease (Glycogen storage disease type II) and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type I and II.

Swallowing Examination

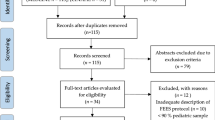

143 out of 152 pediatric swallowing examinations could be completed as pediatric FEES. In four cases FEES was not performed due to lack of indication. In five cases the examination was discontinued due to lack of compliance (n = 4) or the presence of choanal stenosis (n = 1) (see Fig. 2).

FEES could be performed in children of all ages. Even in the neo-intensive care bed and in patients under monitoring and/or with an inserted nasogastric tube, the examination could be carried out well. No complications (e.g., epistaxis, apnea) appeared.

The number of examinations increased continuously from 9 in 2015 up to 42 in 2019. In the first 6 months of 2020, 26 children have already been assessed despite a lockdown due to COVID-19.

The gender distribution of children with dysphagia was almost equal (see Table 3). Aspiration was recorded in eight girls and eight boys. In the 15 children with suspected behavioral feeding disorders, the male gender was more frequently affected (3:1).

PAS value was documented in 31 examinations (media n = 1, range 1–8). The highest percentage of missing data was found for laryngopharyngeal sensation and delayed swallowing reflex (see Table 4).

Impact of Underlying Diseases on Dysphagia

Logistic regression shows that an underlying disease significantly increases the chance of having a positive dysphagia finding (OR 13.08, 95% CI 3.66 to 46.65, p = 0.00). More precisely the categories genetic syndrome (OR 2.60, 95% CI 1.15 to 5.88) and neurologic disorder (OR 4.23, 95% CI 1.31 to 13.69) were associated with a higher chance of dysphagia. In children, without any known disease (n = 25) dysphagia was found in only three cases (see Table 5).

Discussion

Clinical Observations

In our study, FEES could be performed in children without complications with a completion rate of 96.7%. This decent value can certainly be attributed to the experience of the examiners, as well as the thin diameter of the endoscope, and the consequent use of topical nasal anesthesia [31]. In agreement with Miller and Willging [22], FEES can be confirmed as a feasible and safe procedure for infants, children, and adolescents.

Of the 128 examined children with a suspected swallowing disorder, 54% actually suffered from dysphagia. Aspiration was found in 13.5% of the cohort. In most cases, adequate clearing was performed spontaneously. Only 18.7% of aspirations were silent. This is a moderate rate compared to other studies [20]. It is worth noting that the diagnosis of no dysphagia was referred to as absence of pharyngeal swallowing pathologies in FEES. The examiners stated that among the children without pharyngeal pathologies there were definitely children with an oral swallowing disorder.

Logistic regression showed that preexisting or chronic diseases implicate higher odds for children to suffer from pharyngeal dysphagia. Due to the specialization of the cooperating university children´s hospital, the examined cohort comprised a large number of children with genetic syndromes (N = 43), including children with rare diseases.

Certainly, this comparatively high proportion of children with a severe or syndromic underlying disease and already existing suspicion of dysphagia leads to a preselection in our cohort. This bias is also evident in other studies that include, for example, a large number of preterm [32] or post-heart surgery patients [33]. Valid data on the dysphagia prevalence in these patient cohorts do currently not exist and only a few studies on endoscopic dysphagia diagnostics have been published. For a better understanding of the swallowing disorders in these children, valid studies are still urgently needed.

Overall, there has been a continuously increasing demand for interdisciplinary swallowing examinations, which has led to an increase in cases of pediatric dysphagia over the past five years.

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Although a standard FEES protocol has been described for adult patients, [28] and is well established in our university dysphagia center, there is currently no standard procedure for pediatric FEES. This analysis shows that a lack of standard protocol in pediatric FEES causes poor documentation and thus missing values. Probably, if not documented, pathological parameters of the swallowing act such as aspiration and penetration did not occur. This leads to the bias, that the distinction between absence of pathology and not tested cannot be clearly made in this way. Concerning the less frequently documented findings as delayed swallowing reflex and laryngopharyngeal sensation, it can be supposed that these were not always routinely examined and documented and could therefore be incorrectly interpreted as a lack of pathology.

Interestingly, a classification of the findings using a rating scale such as the PAS was only carried out in 31 of the analyzed examination documentations. This can be explained by the fact that PAS is well established in adult FEES but cannot simply be transferred to children. This underlines the need for a universally validated assessment standard in children.

Standardized documentation of the pharyngeal pathologies should at least include the presence, the absence, or the statement not tested/not assessable for the relevant items. From our point of view, the findings early spillover, delayed swallowing reflex, penetration, aspiration, clearing, residue and laryngopharyngeal sensation would be recommended. To form the basis for improved interdisciplinary communication and treatment in the future, the effect of compensatory strategies (e.g., positioning, pacing, feeding advice) on these pathologies and the resulting dietary (e.g., thickening fluids) and therapeutic recommendations (e.g., gastric tubes) should be documented as well.

Prospectively, the complete pediatric FEES protocol needs to be standardized with necessary variations regarding individual factors such as age/development status, general condition, utilized materials (endoscope, nasal decongestant, local anesthesia, kind of food dye, and thickener), or nutritional modes. Although modified protocols for pediatric FEES are currently being published [21], they still show gaps concerning the entire spectrum of pediatric patients and leave a lot of space for interpretation.

Another task that should not be neglected will be the standardization of CSE. Our analysis shows a high degree of variability in our CSE implementation. Significant gaps in documentation were identified. Similar inaccuracies are also apparent in other studies. As recently reported by Garand et al. [20], there is a great need for specific guidelines even in CSE.

To address these problems in the future, standardization of the entire diagnostic process of pediatric dysphagia is intended in our university dysphagia center as part of the CIDD-P project (clinical and instrumental dysphagia diagnostic standard—pediatric). This will, on the one hand, ensure the best possible care and on the other hand better comparability of studies on epidemiology, evaluation, and treatment outcome in pediatric patients with dysphagia.

Conclusion

This study shows that FEES in children is well feasible. It also indicates that dysphagia is significantly increased in children with an underlying disease, particularly in genetic syndromes. Despite years of experience in FEES, some deficits in documentation could still be found, which complicates the subsequent scientific processing of data and therefore do not allow for an adequate follow-up. Increased standardization in pediatric FEES is needed. This enables better comparability of studies on epidemiology, assessment, and treatment outcomes of dysphagia in children in the future.

References

Kovacic K, Rein LE, Szabo A, Kommareddy S, Bhagavatula P, Goday PS. Pediatric feeding disorder: a nationwide prevalence study. J Pediatr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.07.047.

Arvedson JC, Lefton-Greif MA. Instrumental assessment of pediatric dysphagia. Semin Speech Lang. 2017;38(2):135–46. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1599111.

Miller CK. Aspiration and swallowing dysfunction in pediatric patients. ICAN: Infant Child AdolescNutr. 2011;3(6):336–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941406411423967.

Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller A-B, Lumbiganon P, Petzold M, Hogan D, Landoulsi S, Jampathong N, Kongwattanakul K, Laopaiboon M, Lewis C, Rattanakanokchai S, Teng DN, Thinkhamrop J, Watananirun K, Zhang J, Zhou W, Gülmezoglu AM. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(18)30451-0.

Arens C, Herrmann IF, Rohrbach S, Schwemmle C, Nawka T. Position paper of the German Society of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, Head and Neck Surgery and the German Society of Phoniatrics and Pediatric Audiology—current state of clinical and endoscopic diagnostics, evaluation, and therapy of swallowing disorders in children and adults. Laryngorhinootologie. 2015;94(Suppl 1):S306-354. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1545298.

Dodrill P, Gosa MM. Pediatric dysphagia: physiology, assessment, and management. Ann NutrMetab. 2015;66(Suppl 5):24–31. https://doi.org/10.1159/000381372.

Goday PS, Huh SY, Silverman A, Lukens CT, Dodrill P, Cohen SS, Delaney AL, Feuling MB, Noel RJ, Gisel E, Kenzer A, Kessler DB, Kraus de Camargo O, Browne J, Phalen JA. Pediatric feeding disorder: consensus definition and conceptual framework. J PediatrGastroenterolNutr. 2019;68(1):124–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000002188.

Bhattacharyya N. The prevalence of pediatric voice and swallowing problems in the United States. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(3):746–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24931.

Jaafar NH, Othman A, Majid NA, Harith S, Zabidi-Hussin Z. Parent-report instruments for assessing feeding difficulties in children with neurological impairments: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(2):135–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13986.

Lefton-Greif MA, Okelo SO, Wright JM, Collaco JM, McGrath-Morrow SA, Eakin MN. Impact of children’s feeding/swallowing problems: validation of a new caregiver instrument. Dysphagia. 2014;29(6):671–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9560-7.

Craig GM. Psychosocial aspects of feeding children with neurodisability. Eur J ClinNutr. 2013;67(Suppl 2):S17-20. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2013.226.

Heckathorn DE, Speyer R, Taylor J, Cordier R. Systematic review: non-instrumental swallowing and feeding assessments in pediatrics. Dysphagia. 2016;31(1):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-015-9667-5.

Cerezo CS, Lobato DJ, Pinkos B, LeLeiko NS. Diagnosis and treatment of pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders. ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition. 2011;3(6):321–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941406411420141.

Prasse JE, Kikano GE. An overview of pediatric dysphagia. ClinPediatr (Phila). 2009;48(3):247–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922808327323.

Calvo I, Conway A, Henriques F, Walshe M. Diagnostic accuracy of the clinical feeding evaluation in detecting aspiration in children: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(6):541–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13058.

Bowman OJ, Hagan JL, Toruno RM, Wiggin MM. Identifying aspiration among infants in neonatal intensive care units through occupational therapy feeding evaluations. Am J OccupTher. 2020. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.022137.

Pavithran J, Puthiyottil IV, Narayan M, Vidhyadharan S, Menon JR, Iyer S. Observations from a pediatric dysphagia clinic: characteristics of children at risk of aspiration pneumonia. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(11):2614–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.27654.

Duncan DR, Mitchell PD, Larson K, Rosen RL. Presenting signs and symptoms do not predict aspiration risk in children. J Pediatr. 2018;201:141–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.030.

Lundine JP, Dempster R, Carpenito K, Miller-Tate H, Burdo-Hartman W, Halpin E, Khalid O. Incidence of aspiration in infants with single-ventricle physiology following hybrid procedure. Congenit Heart Dis. 2018;13(5):706–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/chd.12636.

Garand KLF, McCullough G, Crary M, Arvedson JC, Dodrill P. Assessment across the life span: the clinical swallow evaluation. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020;29(2S):919–33. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00063.

Miller CK, Schroeder JW Jr, Langmore S. Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing across the age spectrum. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020;29(2S):967–78. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_AJSLP-19-00072.

Miller CK, Willging JP. Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in infants and children: protocol, safety, and clinical efficacy: 25 years of experience. Ann OtolRhinolLaryngol. 2020;129(5):469–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489419893720.

Willette S, Molinaro LH, Thompson DM, Schroeder JW Jr. Fiberoptic examination of swallowing in the breastfeeding infant. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(7):1681–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25641.

Mills N, Keesing M, Geddes D, Mirjalili SA. Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in breastfeeding infants with laryngomalacia: observed clinical and endoscopic changes with alteration of infant positioning at the breast. Ann OtolRhinolLaryngol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489420965636.

Vetter-Laracy S, Osona B, Roca A, Pena-Zarza JA, Gil JA, Figuerola J. Neonatal swallowing assessment using fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES). PediatrPulmonol. 2018;53(4):437–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.23946.

Suterwala MS, Reynolds J, Carroll S, Sturdivant C, Armstrong ES. Using fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing to detect laryngeal penetration and aspiration in infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2017;37(4):404–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.239.

Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996;11(2):93–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00417897.

Langmore SE, Schatz K, Olsen N. Fiberoptic endoscopic examination of swallowing safety: a new procedure. Dysphagia. 1988;2(4):216–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02414429.

Graf S, Keilmann A, Dazert S, Deitmer T, Stasche N, Arnold B, Löhler J, Arens C, Pflug C. Training curriculum for the certificate “diagnostics and therapy of oropharyngeal dysphagia, including fees”, of the german society for phoniatrics and pedaudiology and the german society for otolaryngology, head and neck surgery. Laryngorhinootologie. 2019;98(10):695–700. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0987-0517.

Pflug C, Flügel T, Nienstedt JC. Developments in dysphagia diagnostics: presentation of an interdisciplinary concept. HNO. 2018;66(7):506–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00106-017-0433-x.

O’Dea MB, Langmore SE, Krisciunas GP, Walsh M, Zanchetti LL, Scheel R, McNally E, Kaneoka AS, Guarino AJ, Butler SG. Effect of lidocaine on swallowing during FEES in patients with dysphagia. Ann OtolRhinolLaryngol. 2015;124(7):537–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489415570935.

Davis NL, Liu A, Rhein L. Feeding immaturity in preterm neonates: risk factors for oropharyngeal aspiration and timing of maturation. J PediatrGastroenterolNutr. 2013;57(6):735–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182a9392d.

Raulston JEB, Smood B, Moellinger A, Heinemann A, Smith N, Borasino S, Law MA, Alten JA. Aspiration after congenital heart surgery. PediatrCardiol. 2019;40(6):1296–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-019-02153-9.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. All authors have reviewed and approved the contents of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Video 1 Excerpts from a FEES recording of an adolescent (14 years old), swallowing thickened liquid, liquid and solid. (AVI 10032 kb)

Video 2 Excerpts from a FEES recording of an infant (24 months), drinking milk from a bottle and eating fruit puree. (AVI 17957 kb)

Video 3 Excerpts from a FEES recording of a child (6,5 years), swallowing yogurt and liquid. (AVI 14548 kb)

Video 4 Excerpt from a FEES recording of a child (6,2 years, nasogastric tube in place), swallowing a small amount of liquid. (AVI 7566 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zang, J., Nienstedt, J.C., Koseki, JC. et al. Pediatric Flexible Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing: Critical Analysis of Implementation and Future Perspectives. Dysphagia 37, 622–628 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-021-10312-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-021-10312-5