Abstract

Tau is a microtubule-associated protein that plays crucial roles in physiology and pathophysiology. In the realm of dementia, tau protein misfolding is associated with a wide spectrum of clinicopathologically diverse neurodegenerative diseases, collectively known as tauopathies. As proposed by the tau strain hypothesis, the intrinsic heterogeneity of tauopathies may be explained by the existence of structurally distinct tau conformers, “strains”. Tau strains can differ in their associated clinical features, neuropathological profiles, and biochemical signatures. Although prior research into infectious prion proteins offers valuable lessons for studying how a protein-only pathogen can encompass strain diversity, the underlying mechanism by which tau subtypes are generated remains poorly understood. Here we summarize recent advances in understanding different tau conformers through in vivo and in vitro experimental paradigms, and the implications of heterogeneity of pathological tau species for drug development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction and prion concepts

Strain phenomena in microbiology

In living systems, the term “strain” can be used to describe a subtype of biological species that is associated with heritable phenotypic properties. The concept of strains is commonly encountered in microbiology where it can apply to bacteria (e.g., methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; Spaulding et al. 2012) and viruses (e.g., SARS-CoV-2; Elslande et al. 2021). Bacteria and viruses are complex molecular systems having multiple components, including constituent proteins. These proteins are encoded within the genomic nucleic acids of the bacterium or virus. These genomic nucleic acids can sustain a mutation(s) in coding sequences, changing the phenotypic properties of bacteria or viruses. Some changes will confer a selective advantage and the mutation will be passed on by the process of replication of the DNA (or RNA) genome as the agent propagates, causing the phenotypic property to be stably inherited. The observed stability of the phenotypic property may be referred to as a “true breeding” behavior. Furthermore, new strains of interest may derive from additional mutations in genomic nucleic acids; for example, the omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 (Karim and Karim 2021) comprises a notorious and timely example of an emerging viral strain in a public health context.

All these concepts lie safely within the accepted rules of molecular biology, “the central dogma”, wherein information flows from genomic nucleic acid to messenger RNA to protein. Less intuitively, and seeming to contravene this scheme (Crick 1970; Oesch et al. 1985), changes in proteins can be heritable in experimental systems in the absence of causative mutations in nucleic acids. To understand the strange and fascinating case of protein-based inheritance and protein-based strains, it is necessary to briefly consider research performed in preceding decades.

Scrapie disease and the scrapie agent

Scrapie in sheep is a neurodegenerative disease well known to veterinarians and the means of its spread between animals and the environment are of both practical and theoretical importance. It was known that the disease could be transmitted in a lab setting by inoculation and while this led to the assumption that a conventional virus was at work, this experimental approach was valuable in allowing systematic and unbiased studies into the composition and properties of the disease-causing agent, i.e., by examination and manipulation of the inoculum derived from the tissues of affected animals. Purification approaches did not yield convincing evidence for a genomic nucleic acid (Kellings et al. 1992) but quite early on they did reveal a protein (Prusiner 1982) that co-purified with infectivity and subsequently proved to be encoded by a chromosomal gene (Oesch et al. 1985; Kretzschmar et al. 1986). The infectious protein was called the prion protein, PrP, and a benign cellular counterpart (in fact, its precursor) was called the cellular prion protein. These two protein isoforms—both modified by asparagine (N)-linked glycosylation and by addition of a GPI-anchor—were revealed to have the same amino acid sequence (Basler et al. 1986) and were discerned by low-resolution techniques as being alternative conformers (Caughey and Raymond 1991; Pan et al. 1993). The two isoforms are designated by the terms PrPSc and PrPC (“Sc” being short for scrapie, C for cellular). At a simple practical level, PrPSc preparations exhibit some resistance to in vitro digestion with broad-spectrum proteases such as proteinase K (PK), while PrPC is susceptible. In terms of replication mechanisms, prions are wildly different from viruses with the disease-causing structural isoform PrPSc templating conformational changes in PrPC, resulting in a net increase in the amount of PrPSc molecules. Regarding nomenclature, the word prion derives from “proteinaceous infectious” particle and, apart from scrapie, there are other diseases—for example, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in humans—with related mechanisms and these are collectively termed as prion diseases.

Strains in scrapie and other prion diseases

Different scrapie agent isolates (preparations with disease-causing infectivity) were known to result in different phenotypic properties in goats and mice (Pattison and Jones 1967; Dickinson and Meikle 1969). Generally, prion “strains” can be differentiated from one another based upon patterns of neuropathological damage in different areas of the central nervous system (CNS), the presence or absence of amyloid deposits within the brain, and the incubation period (time-lapse from inoculation to clinical disease) (Collinge 2001; Bartz 2016). Importantly, the strain-specific phenotypic features were often (but not always) stably propagated upon serial passage (Fraser and Dickinson 1973; Bruce 1993) and thus considered to breed true. But, in the absence of convincing evidence for a scrapie agent nucleic acid genome, new explanations were sought to account for these stable and occasionally mutable biological traits. The emerging knowledge about prion protein isoforms comprised a starting point to decode the phenomenon of scrapie strains in molecular terms and an important conceptual advance was that there can be more than one type of PrPSc. Correspondingly, conformational differences between alternative PrPSc species define corresponding strains and ultimately cause different types of clinical phenotypes (Bessen and Marsh 1992).

While this concept was initially established for rodent-adapted prion strains relying upon the electrophoretic banding pattern of the prion protein after PK digestion (the cleavage site of PrPSc is dependent upon the folding state of the prion protein) and/or in vitro deglycosylation, studies exploring the phenotypic diversity of CJD have shown the presence of distinct PrPSc species correlating to specific clinical pathologies (Haïk and Brandel 2011); comparison between variant CJD (vCJD) and sporadic CJD (sCJD) offers a pertinent example. Specifically, vCJD clinical pathology contrasts with known varieties of sCJD with an earlier age of onset, a longer disease duration (14-month average versus 6 months), and deposition of “florid plaques” wherein an amyloid deposit containing PrP is surrounded by a halo of spongy change (Will et al. 1996; Glatzel 2005; Ironside 2012). Biochemically, the differences between PrPSc associated with sCJD and vCJD are partially revealed by their PK digestion profiles and glycosylation patterns (Collinge et al. 1996). In fact, for vCJD, the degree of decoration by N-linked sugars (“glycoform ratio”) is strikingly similar to that found in mad cow disease (bovine spongiform encephalopathy, BSE), leading to the hypothesis that BSE and vCJD are caused by the same PrPSc strain (Hill et al. 1997). In general, human sporadic prion diseases have PrPSc types that can be distinguished by biochemical parameters such as the type and amount of PrPSc fragments after PK treatment, glycosylation profiles, and protease-specific cleavage sites. This phenotypic diversity is partly attributable to genotypic differences, the most notable being a common Met/Val PRNP polymorphism (Parchi et al. 2009, 2011), which can be further subclassified based on physicochemical properties (MM1, MM2, MV1, MV2, VV1, and VV2) (Parchi et al. 1999).

Advances in assay development have provided more options to discriminate different prion strains. In the cell panel assay, two isolates of murine N2a neuroblastoma cells, CAD5 cells, and L929-derived LD9 cells exhibited differential ability to replicate prion strain and thus allow in vitro discrimination of input strains (Mahal et al. 2007). Utilizing luminescent-conjugated polymers (LCPs), it has been shown that different mouse-adapted prion strains can be distinguished optically by their fluorescence spectra (Sigurdson et al. 2007). Moreover, the conformation-dependent immunoassay (CDI) and conformational stability assay (CSA) showed unique conformational features of different prion strains in animal (Safar et al. 1998) and human prion diseases (Safar et al. 2005) in response to progressive chemical denaturation. In addition to these useful, albeit indirect methods, recent cryo-electron microscopic image analysis has provided direct evidence for the key postulate that prion strains represent different PrPSc conformers (Kraus et al. 2021).

From the outside to the inside: prion effects in the cytoplasm

The prion paradigm describes a misfolded protein deriving from a precursor equipped with an N-terminal signal peptide that is made and post-translationally modified in the secretory pathway. While secretion from the cell offers a simple starting point to consider the phenomenon of cell-to-cell spread that fuels disease progression, there were no immediate reasons to consider that the same principles could apply to cytoplasmic proteins. Nonetheless, it became apparent that long-known cytoplasmic inheritance traits in yeast and fungi—traits which breed true—could be explained in terms of templated protein misfolding. The non-Mendelian inheritable traits of [URE3] and [PSI+] are the amyloid prions of Ure2p and Sup35p proteins, respectively (Wickner 1994), resulting in loss of function phenotypes (Wickner et al. 2004; Liebman and Chernoff 2012). In addition, the filamentous fungi Podospora anserina utilizes an incompatibility protein, [Het-s], to form amyloid fibrils when the fungi encounter a genetically different colony (Coustou et al. 1997; Maddelein et al. 2002). These prions have propelled the consideration of a broader view of cytoplasmic proteins demonstrating self-propagating conformational change. This broader view has now come to encompass the tau protein and tauopathies.

Tau protein and tauopathies

Microtubule-associated protein tau

So, what is the tau protein? Tau proteins derive from the MAPT gene which, unlike Prnp, is subject to alternative splicing in the coding region. Thus, there are six low molecular weight microtubule-associated protein isoforms produced by alternative splicing mRNAs emanating from the MAPT gene located on chromosome 17q21 (Fig. 1a) (Goedert et al. 1988, 1989). Tau is expressed in animal species including, but not limited to, human, mouse, rat, bovine, guinea pig, and zebrafish (Himmler Adolf 1989; Takuma et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2009). In the nervous system, tau mRNA is expressed predominantly in neuronal cells, although a lower expression level of tau has been detected in various types of glial cells, such as oligodendrocytes and astrocytes (Müller et al. 1997; Gorath et al. 2001). Similar to other microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs), one of the physiological functions of tau is to bind microtubules, stabilize and mediate their assembly, and modulate vesicle/organelle transport on microtubules (Weingarten et al. 1975; Binder et al. 1985; Black et al. 1996). Intracellular tau is primarily located in the axons and to a lesser extent in somatodendritic compartments such as the cell membrane (Arrasate et al. 2000), mitochondria (Li et al. 2016), and nucleus (Wang et al. 1993). Depending on its cellular localization, tau also plays important roles in axonal transport (Rodríguez-Martín et al. 2013; Lacovich et al. 2017; Morris et al. 2021), nucleic acid protection (Sultan et al. 2011; Violet et al. 2014), synaptic plasticity (Spires-Jones and Hyman 2014), and neuronal maturation (Fiock et al. 2020).

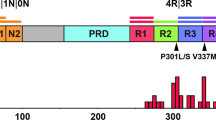

Alternative splicing of MAPT gene and tau protein aggregation. a MAPT gene and six splicing isoforms of tau. The promoter lies in the 5′ end of exon 1 (Liu and Gong 2008). Exons 0 and 14 are transcribed but not translated as they are a part of the 5′-untranslated sequence (5′-UTR) and the 3′-untranslated sequence (3′-UTR), respectively (Liu and Gong 2008; Sud et al. 2014). In the adult human brain, alternative splicing of exons 2, 3, and 10 gives rise to all six isoforms of tau; exons 4A, 6, and 8 are exclusive to the peripheral nervous system and absent in the human brain (Kang et al. 2020a). b A schematic representation of native soluble monomeric 4R tau adapting a different conformation and forming insoluble aggregates. In the aggregated form of tau, the β-structure-rich core is primarily composed of the microtubule-binding domain, flanked by a loosely structured “fuzzy coat”. Tau molecule is not drawn to scale. c Tau filament cores derived from various tauopathies were depicted as three consecutive rungs, consisting of microtubule-binding repeats and a few additional residues

Among 16 exons in the tau primary transcript, exons 2, 3, 4a, 6, 8, and 10 are subject to alternative splicing and exons 1, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, and 13 are constitutive (Kang et al. 2020b) (Fig. 1a). In general, tau splicing isoforms differ by the number of N-terminal regions (0 N, 1 N, or 2 N) as well as the number of conserved repeat motifs (3R or 4R) (Goedert et al. 1989). Functionally, the N-terminal regions may influence spacing between microtubules (Frappier et al. 1994), subcellular distribution of neuronal tau (Chen et al. 1992; Liu and Götz 2013), and aggregation kinetics of tau (Zhong et al. 2012). The repeat motifs constitute the microtubule-binding domain of tau, and the proline-rich domain (PRD) links the C-terminal assembly domain and the N-terminal projection domain. Overall, due to its high content of polar and charged amino acids, tau is a highly hydrophilic and water-soluble protein. As a result, tau lacks a well-defined 3-dimensional structure and instead possesses great structural flexibility. Structural biology studies confirm that natively folded tau is indeed an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) (Mukrasch et al. 2009; Cordeiro et al. 2017).

Due to its structural plasticity, tau possesses the tendency to change its global conformations to form protein aggregates that are energetically favorable, detergent-insoluble, protease-resistant (Novak et al. 1993) and can be stained with amyloid dyes (e.g., Thioflavin S, Congo Red, and their derivatives) (Styren et al. 2000; Shin et al. 2021) (Fig. 1b). This dramatic structural alteration and formation of protein aggregates lie at the heart of a range of tau-related neurodegenerative diseases—tauopathies.

Tauopathies

The term “tauopathy” represents a family of neurodegenerative disorders pathologically characterized by the presence of insoluble intracellular tau inclusions in the central nervous system (CNS) and clinically characterized by dementia and/or parkinsonism (Kovacs 2015). Classical tauopathies include, but are not limited to, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism mapping to the MAPT gene on chromosome 17 (FTDP-17 T, also known as FTLD-MAPT), Pick’s disease (PiD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), argyrophilic grain disease (AGD) (Lee et al. 2001; Wang and Mandelkow 2016), and sporadic multiple system tauopathy with dementia (Bigio et al. 2001).

Pathologically, neurofibrillary lesions in the brain directly correlate with the progression of AD as pathogenic tau propagates through the connected neural network. The Braak staging system of AD (Table 1) was derived before concepts of prion-like protein spreading were in common usage yet can be interpreted to indicate that certain anatomical regions in the brain become sequentially “infected” with pathogenic tau to cause each clinical stage of the disease. Correspondingly, there is a loose correlation between tau spreading to additional neuroanatomical structures and progression of clinical disease (Braak and Braak 1995).

Although pathogenic tau is not infectious in the sense that a person afflicted by a tauopathy is contagious to other people or can spread disease by contaminated surgical instruments, experiments performed in both tissue culture (Frost et al. 2009) and animal models (De Calignon et al. 2012) led to the idea that pathological forms of tau in an area of affected tissue might be contagious to adjacent healthy tissues. In a cell biological sense, abnormal tau can be released into the extracellular space and be taken up by neighboring cells. Several mechanisms may support intercellular tau transfer: (1) ectosomes and exosomes carry pathogenic tau in vesicles, which upon simple fusion and endocytosis may release tau seeds to recipient cells (Dujardin et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2017); (2) tunneling nanotubes act as intercellular bridges to facilitate tau fibril transfer (Tardivel et al. 2016); (3) heparan sulfate proteoglycan mediates macropinocytosis of tau seeds (Holmes et al. 2013). When taken in by naïve cells, pathogenic tau conformers stimulate natively folded tau to adopt an alternative conformation (misfold), leading to the spread of tau pathology. Interestingly, natively folded monomeric tau is also subject to efficient intercellular trafficking between neurons, suggesting that transport of tau may be a constitutive biological process as well as occurring in disease (Evans et al. 2018). In an experimental realm, the “infectious” nature of pathogenic tau can be exploited to establish models of tauopathies—inoculation of tau seeds (in vivo or in vitro generated) into tissue culture (Sanders et al. 2014), organoids (Gonzalez et al. 2018), and transgenic/nontransgenic animal models (Narasimhan et al. 2017; He et al. 2020) have become a common experimental approach.

Functions of tau are largely dependent on its post-translational modifications (PTMs), including phosphorylation, glycation, nitration, acetylation, oxidation, sumoylation, ubiquitylation, polyamination, isomerization, and addition of β-linked N-acetylglucosamine (Guo et al. 2017). Abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau, which is a cardinal component of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), is seen in various types of tauopathies including, but not limited to, AD, FTDP-MAPT, and PSP (Iqbal et al. 2005). The phosphorylation state of tau has significant implications on neuronal health in various ways: (1) it alters the binding property of tau to microtubules, hence detaching tau from MTs and destabilizing them (Lindwall and Cole 1984; Mandelkow et al. 1995); (2) it alters the binding property of tau to interacting partners and disturbs tau-mediated signaling pathways (Heinisch and Brandt 2016); (3) it results in a high local concentration of tau (Chang et al. 2011), possibly promoting its aggregation; (4) it disrupts the intracellular route of tau degradation (Nakamura et al. 2012). Accordingly, the mechanisms by which tau contributes to neurological disorders may be multifaceted. It is noteworthy that loss of normal function for tau does not explain the whole picture of tau-related neurodegeneration as tau knock-out mice only display mild phenotypes (e.g., muscle weakness and hyperactivity) instead of neurodegeneration (Ikegami et al. 2000). Thus, gain-of-function abnormalities caused by tau misregulation appear to be major contributors to tau pathologies.

In many non-sporadic/familial tauopathies, mutations in the MAPT gene serve as the main driving force of pathogenesis. These mutations may be exonic or intronic. ALZFORUM (https://www.alzforum.org/mutations/mapt) provides a thorough summary of tauopathy-associated mutations in the MAPT gene. Indeed, several pathogenic mutations lie in the coding regions of exons 9, 10, 11, and 12, corresponding to the repeated microtubule-binding domain of tau (Fig. 1). Many mutations have significant effects on tau aggregation and microtubule assembly. For instance, I260V in exon 9 of the MAPT gene enhances tau aggregation and undermines microtubule assembly (Grover et al. 2003). Similar effects have also been observed in mutations associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration, such as P301L (Chen et al. 2019) and P301S (Kundel et al. 2018). Unlike the exonic mutation, the intronic mutations in the MAPT gene exhibit their pathogenic potential by affecting the ratio of 3R:4R spliced mRNAs. In fact, most intronic mutations cause more frequent inclusion of exon 10 and result in an overproduction of 4R tau, including IVS9-10 G > T (Olszewska et al. 2021), IVS10 + 3 G > A (Spillantini et al. 1998), IVS10 + 11 T > C (Taylor et al. 2001), IVS10 + 12 C > T (Yasuda et al. 2000), IVS10 + 13 A > G (Hutton et al. 1998), IVS10 + 14 C > T (Hutton et al. 1998), IVS10 + 15 A > C (McCarthy et al. 2015), and IVS10 + 16 C > T (Hutton et al. 1998). Two exceptions are IVS9-15 T > C (Anfossi et al. 2011) and IVS10 + 19 C > G (Stanford et al. 2003), where they both lead to less frequent inclusion of exon 10 and overproduction of 3R tau.

Either 3R or 4R tau may become the predominant pathological tau isoform in different diseases, as shown in Table 2. Due to the additional repeat motif R2, 4R tau displays a higher affinity to microtubules than 3R tau and is thus more efficient at mediating microtubule assembly (Goedert and Jakes 1990). 3R and 4R tau are found in the adult human brain with an approximate 1:1 ratio (Sergeant et al. 1997) and 3R:4R tau isoform imbalance may have significant implications in tau-related pathogenesis (Lacovich et al. 2017).

Apart from the involvement of tau splicing isoforms, the histopathology of tauopathies is further complicated with the presence of different types of tau aggregates. Figure 1c offers examples for observations made in AD, CTE, PiD, and CBD. The tau filament core (β-strands) from brains of AD and CTE includes R3 and R4 microtubule-binding repeats (Fitzpatrick et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2020). However, pathological tau aggregates in AD appear as neurofibrillary tangles (fibrillar intracytoplasmic inclusions) and neuropil threads (swollen filament-containing dendrites and distal axons/terminals) (Braak and Braak 1991), whereas NFTs and thorn-shaped astrocytes are present in CTE (Arena et al. 2020). As a 3R tauopathy, PiD has prominent neuronal tau inclusions (Pick bodies) and glial tau inclusions (less frequent but include ramified astrocytes and Pick-body-like inclusions in oligodendrocytes) (Komori 1999). In CBD, a 4R tauopathy, tau aggregates are histopathologically characterized by pre-tangles in neurons, astrocytic plaques in distal processes, and coiled bodies in oligodendrocytes (Ferrer et al. 2014). Heterogeneity of pathological tau filaments represent one aspect of the complex nature of tauopathies. In the following sections, we offer more in-depth discussions about the molecular diversity of tau considering animal models and biochemical characterization of misfolded tau. The implications of heterogeneity of pathological tau for therapeutic development are also considered.

Tau strain heterogeneity and animal models

Similar to infectious prion protein (PrPSc), tau misfolding does not only produce one type of pathogenic tau but instead gives rise to an array of distinct conformers (Eskandari-Sedighi et al. 2017; Daude et al. 2020). These pathogenic tau species self-assemble and propagate indefinitely in living systems. Some of the early evidence for the existence of tau strains came from studies where human tauopathy isolates were inoculated into a foreign host species. For instance, when human tauopathy extracts from PSP, CBD, and AGD were inoculated into the brains of ALZ17 mice (expressing only human 2N4R tau), the immunohistochemistry patterns in mice resembled corresponding human pathology profiles (Clavaguera et al. 2013). But, unlike prion diseases where there is no alternative splicing and there is only one primary structure for PrPC (Basler et al. 1986), heterogeneity in clinical manifestation of human tauopathies does not automatically indicate the existence of tau conformer strains, as physiological alternative splicing to generate different tau substrates has to be considered. However, using transgenic mice expressing equal ratios of 3R and 4R human tau, it was recently demonstrated that the transmission of distinct tau conformers is independent of the composition of alternatively spliced isoforms (He et al. 2020). This supports the tau strain hypothesis: distinct tau strains (misfolded tau with different conformations) will result in distinct neuropathologies (Sanders et al. 2014).

The ability to model tau accumulation and aggregation in animals is an important practical consideration that facilitates research into strains. Tau deposition can be seeded in the brain by a prion-like process when preparations of pathogenic tau are injected intracerebrally into transgenic tau (TgTau) mice expressing a human tau coding sequence (Sanders et al. 2014; Boluda et al. 2015; Kaufman et al. 2016). In the absence of seeding, TgTau mouse models normally begin to manifest tau deposits at different ages (Table 3), often markedly dependent upon the expression level of transgenic tau. Like human tauopathies (Fig. 1c, Table 2), tau deposits may manifest in different cell types within the brains of Tg models, of potential relevance to understanding the cellular tropism of injected tau strains. In experimental seeding paradigms, injection of a small amount of pathogenic tau-rich brain extracts or cell lysates into the brains of host TgTau mice induces accelerated tau deposition that spreads from the injection site to connected brain regions (Boluda et al. 2015). TgTau mice exhibit differences in histological profiles and in molecular structural features in misfolded tau when inoculated with distinct brain-derived (Narasimhan et al. 2017) and biosensor cell-derived (Sanders et al. 2014) tau aggregates. The short summary of tau models captured in Table 3 also highlights a skew in this resource where Tg models are frequently based upon FTLD-MAPT mutations rather than expressing WT human tau; in consequence, they recapitulate processes in genetic tauopathies, but not necessarily the events of idiopathic tauopathies. Rodents expressing WT human tau offer advantages for studying seeds derived from idiopathic tauopathies because they do not necessarily develop striking spontaneous pathology in the absence of seeding (Probst et al. 2000). In other words, the dynamic range for detecting experimental seeding may be greater (because of a lower noise floor) in recipient animals without FTLD-MAPT mutations in their tau protein (He et al. 2020).

Longitudinal and cross-sectional experimental designs in animal models can offer insights into molecular events in the early stages of pathogenesis and, potentially, the genesis of tau strains. However, the expression level is another important parameter and a potential confound in animal modeling. Some currently adopted tauopathy mouse models significantly overexpress tau to hasten pathogenesis and may fail to accurately depict the conditions relating to human sporadic tauopathies (Jankowsky and Zheng 2017) (i.e., an aged central nervous system expressing low levels of tau). Table 3 lists commonly used mouse models for tauopathy. To the best of our knowledge, most of them are not reported to capture naturally occurring phenotypic diversity in disease manifestation. Interestingly, TgTau(P301L)23,027 associates with a later disease onset (12–13 months), likely due to its low expression level of human mutant tau estimated at 1.7 × endogenous levels (Murakami et al. 2006). This slow model of primary tauopathy exhibits pathological and biochemical features of FTLD-MAPT, such as age-dependent accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau, neuro- and glial-fibrillary tangles in the brain, and neuronal damage in the temporal and hippocampal formations (Murakami et al. 2006). Derivatives of the same mouse model (on three different genetic backgrounds) demonstrated neuronal loss, filamentous tau formation, and delayed onset of symptoms (in the last 40% of the animals’ natural lifespan), confirming and extending observations made with the original transgenic line (Eskandari-Sedighi et al. 2017). Since these Tg mice exhibit phenotypic diversity even within independent inbred genetic backgrounds—likely due to environmental factors (Eskandari-Sedighi et al. 2017)—they may be mimicking the heterogeneity that is naturally present in human tauopathies with the same tau mutation. When the origin of heterogeneity was more thoroughly examined using cell biological, biochemical, and biophysical methods (tau seeding assay, limited proteolysis, conformation-dependent immunoassay, and electron microscopy), it became clear that these lower expresser TgTauP301L mice generate diverse, distinct tau aggregate species (Daude et al. 2020; Dujardin et al. 2020).

Biochemical and biophysical characterization of tau strains

Tau strains have been classified according to different parameters. In vivo hallmarks include clinical signs (e.g., behavioral and memory assessment) and profiles of histological damage. Apart from these, each tau strain is associated with a specific cluster of biochemical features characterizing the fibrils. Among them, the most commonly reported methods depend on resistance to denaturation by chaotropic agents (Daude et al. 2020), seeding behaviors in tau reporter cell lines (Kaufman et al. 2016), electrophoretic mobility after protease digestion (limited proteolysis) (Eskandari-Sedighi et al. 2017), and biophysical analysis of tau fibrils (Daude et al. 2020). These assays listed above can be used for different starting materials, such as human/mouse brain-derived tau extracts, pathogenic tau propagated in reporter cell lines, and in vitro generated tau fibrils.

Seeding assay in tau reporter cells

To study tau protein aggregation, immortalized cell lines are often used to stably express full-length or truncated forms of tau substrate with or without pathogenic mutations, allowing for intracellular templated amplification after the introduction of malformed tau species as seeds. Many cell lines are experimentally used for this purpose, including but not limited to N2a (Matsumoto et al. 2018), HEK293 (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2007; Holmes et al. 2014; Sanders et al. 2014; Kaufman et al. 2016; Kang et al. 2021), HeLa (Li et al. 2021), and SH-SY5Y (Löffler et al. 2012). Immortalized cell lines offer useful tools to investigate tau protein behaviors in a cellular environment. Experimental factors such as the source of tau seed and genotype of recipient cells (Fig. 2a) may influence the outcome and thus deserve careful consideration.

Seeding assay in tau biosensor cell lines. Experimental parameters regarding pathogenic tau seed and recipient biosensor cell type dictate the cellular phenotypes after transduction—the experimental outcome a. Tau inclusions appeared with heterogeneous morphologies, when the non-seeded cells b, c were transduced with seed-competent tau materials, such as brain homogenate of transgenic mice, TgTauP301L (Daude et al. 2020). The morphologies include irregular large clusters in the cytoplasm (amorphous, d, e), perimeter signals along with the nuclear edges (nuclear envelope, f, g), small bead shapes with various sizes (speckles, h, i), and cytoplasmic fibril-like strip form inclusions (threads, j, k). Tau in green; nuclei in blue. Scale bars, 10 µm

Stably expressing tauRD(LM)-YFP fusion protein substrate, a genetically engineered HEK293 tau aggregation reporter cell line can exhibit morphologically distinct, fluorescent intracellular tau inclusions when exposed to different sources of pathogenic tau (Fig. 2b). Conceptually similar to work based upon GFP fusion proteins of yeast Sup35p prion substrate (Glover et al. 1997), differences resulting from the introduction of different tau seeds can be indefinitely propagated in a clonal fashion (Sanders et al. 2014). Subsequent work with the same reporter cell line confirmed the hypothesis that tau strains dictate patterns of cell pathology and differentiated 18 strains that result in distinct pathological patterns in the transgenic mouse model (Kaufman et al. 2016). Using a subclone of these reporter cells (Clone 1/DS1), a similar seeding experiment was performed with brain extracts of mouse and human origin. Seeded cells were scored according to the morphology of intracellular tau inclusions by a different criterion—diffuse, amorphous, nuclear envelope, speckles, and threads (Daude et al. 2020). Transgenic mouse brain extracts with different CSA signatures (as discussed in the next section) displayed vastly different seeding profiles and human brain samples with different clinical diagnoses (behavioral variant FTDs with/without predominate memory impairment and semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia) showed less prominent differences in this assay. When performing seeding assays with immortalized cells, the effect of cell cycle needs to be carefully examined as different tau inclusion morphologies tend to accumulate in different stages of the cell cycle (Kang et al. 2021). In addition, due to the ability to faithfully propagate tau strains in a conformation-specific fashion, tau reporter cell lines have also been used as an avenue for protein amplification to allow for other biochemical analyses, as discussed in later sections.

Conformation-dependent immunoassay and conformational stability assay

In these procedures, tau is first exposed to the protein denaturant guanidine hydrochloride (Gdn HCl) and then exposed to europium-labeled antibody against epitopes that are hidden under native conditions in the absence of Gdn HCl (Safar et al. 1998; Daude et al. 2020). In CDIs, relative signal intensities in the absence and presence of Gdn HCl provide an estimation of the ratio between detergent-sensitive and detergent-resistant proteins. In CSAs, stepwise addition of Gdn HCl generates a guanidine-titration stability profile, providing evidence of strains with distinct conformations (Safar et al. 1993, 1998; Cohen et al. 2015). CDIs and CSAs offer a straightforward comparison of strain properties with relatively simple procedures: thus, (i) CDI ratios and CSA unfolding conformational signatures are independent of the concentrations of the misfolded species; (ii) a tau CDI assay performed against recombinant full-length human tau (tau441) that was deliberately misfolded into fibrils demonstrated a broad linear range for these assays (Daude et al. 2020); and (iii) the procedure does not necessarily involve pre-purification or in vitro amplification steps that can alter the in vivo conformational repertoire and biological properties of strain isolates (Atarashi et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2018). Using human FTLD-MAPT-P301L brain material derived from frontal cortex and mouse P301L brain materials, CSAs indicated multiple co-existing conformers (Daude et al. 2020). It follows that the collection (ensemble) of tau conformers seen at the disease endpoint may have evolved from a precursor population, a complex mixture of misfolded forms seen at an earlier experimental time point. These data illustrate the cloud concept of scrapie strain ensembles (Collinge and Clarke 2007) that were deduced from serial passage inoculation studies but they differ by reflecting co-synchronous origins of strains within a susceptible genotype (i.e., not requiring an experimental inoculation step). Currently, a pan-tau antibody DA9 is most frequently used to monitor the denaturation status of tau. The epitope of DA9 is located between the N-terminal region and the proline-rich domain (a.a. 102–139) (Daude et al. 2020), an area distant from the PHF core. Future employment of antibodies targeting the microtubule-binding region may yield more structural information about the aggregation-competent core of tau.

Limited proteolysis

The limited proteolysis method is based on short, controlled exposures of multimeric tau species to a selected protease. As the proteolytic enzymes cleave proteins more readily at surface-exposed sites, it offers a tool to obtain insights on structural features of aggregated tau, albeit at low resolution. The resultant fragments are then resolved by electrophoresis and detected with antibodies (pan-tau or epitope-specific) or by Coomassie blue staining.

Various proteases have been used to probe the structural differences in distinct tau strains that are extracted from tau reporter cell lines, TgTau mouse brains, or human samples. When studying tauRD cells that are transduced with heparin-induced tau fibrils, a cell-derived tau extract was treated with an enzymatic mixture denoted pronase E; this analysis showed that tau inclusions in independent clones are distinguishable. Specifically, the pronase E-digested tau fragments in clone 9 produced a smear around 12 kDa, whereas clone 10 produced a clear doublet (Sanders et al. 2014). Using the same technique, it was subsequently noted that diverse banding patterns were observed after recombinant, mouse, and human brain samples were inoculated into the same reporter cell line (Kaufman et al. 2016). In addition to pronase E, thermolysin and proteinase K have also been used in an attempt to probe the structural features of tauRD cell-derived tau aggregates (Kang et al. 2021), although it remains possible that structural differences exist between full-length tau fibrils and tauRD fibrils, especially when a biosensor molecule is attached covalently to make a fusion protein.

In transgenic mice expressing a low level of human P301L tau, multiple tau conformers have been found. Considering that in vitro proteolysis alone yields low-resolution structural information, mass spectrometry was used to interrogate the trypsin-resistant core of mouse brain-derived sarkosyl-insoluble tau. Mice with distinct immunohistochemical profiles yielded three trypsin signatures: a doublet (24 kDa and 48 kDa), a quintuplet (14.2 kDa, 19.7 kDa, 20.8 kDa, 23.8 kDa, and 24.4 kDa), and a triplet (20.8 kDa, 24 kDa, and 41.6 kDa) (Daude et al. 2020).

Although limited proteolysis has been employed to directly study human brain homogenate material (Li et al. 2021), two practical considerations limit the sensitivity of this assay: first, limited proteolysis relies on protease-resistant tau species (e.g., detergent-insoluble tau fibrils) which, in certain cases, may have a low abundance in brain homogenates. For instance, the abundance of sarkosyl-insoluble tau is low in transgenic mice at a young age (Jackson et al. 2016; Metaxas et al. 2019); second, a large amount of sample may be consumed in establishing a working ratio between tau and protease. One alternative here is to use in vitro or in-cell amplified tau fibrils as a proxy to investigate properties of the original inoculum. For example, in vitro amplification served as an important step to study the structural differences between (i) heparin-induced tau fibrils, (ii) tau fibrils assembled in the absence of an added co-factor, and (iii) neurofibrillary tangles extracted from human brain samples (Guo et al. 2016). During this process, recombinant 2N4R human tau was seeded with the pathogenic tau preparations to augment the quantity of samples for trypsin and proteinase K digestion. Similarly, human brain-derived tau seeds were effectively propagated in tau reporter cells, allowing pronase E digestion to act as a method to distinguish them from other sources of tau seeds (recombinant and mouse) (Kaufman et al. 2016).

It is noteworthy that different tau conformers may not necessarily become distinguishable by use of a single protease as an analytical reagent since similar or identical bands may be detected after proteolysis. One workaround is to use a panel of proteases, while the second workaround is to use a titration series. Thus, when comparing transgenic mouse brain-derived P301S tau aggregates to recombinant P301S fibrils, it became evident that these two tau conformers have different resistance to PK digestion, although their fragments have similar apparent molecular weights deduced from gel mobility (Falcon et al. 2015). Alternatively, limited proteolysis may also be performed with varying concentrations of a detergent while using an unchanged concentration of protease. This is to measure the rate at which aggregated tau becomes unfolded by the detergent—a similar technique to the conformational stability assay. To analyze misfolded tau in human AD, CBD, and PSP brains, tau fibrils were titrated with 1–3 M of guanidine hydrochloride in the presence of proteinase K and subsequently differentiated according to their PK resistance (Narasimhan et al. 2017).

Biophysical characterization

Although various histological and biochemical analyses strongly suggested the existence of different tau conformers, knowledge at the structural level of tau remained superficial without the recent application of biophysical techniques (Zweckstetter et al. 2017). In the context of tau misfolding, one main challenge is to characterize the protein aggregates in solution state. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), a commonly used method to assess the structural features of proteins in solution, has been occasionally employed to characterize the disorder-to-order transition in tau misfolding (Mylonas et al. 2008; Choi et al. 2009; Shkumatov et al. 2011). Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (ssNMR) offers an alternative avenue for amyloid analysis and has been used to study the conformational changes of various regions upon tau misfolding, such as the microtubule-binding domain (Daebel et al. 2012) and the proline-rich domain region (Sillen et al. 2005; Savastano et al. 2020). Despite their considerable potential, to the best of our knowledge, SAXS and ssNMR have only been marginally used to distinguish different tau conformers, possibly owing to their limitations in resolution (Petoukhov and Svergun 2013) and sensitivity (Chatham and Blackband 2001).

As a static imaging tool, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) allows for direct visualization of purified tau fibrils at nanometer resolution (Huseby and Kuret 2015). Commonly used parameters for tau fibril assessments are morphology, filament lengths, fiber widths, and twist periodicity. In AD, the neurofibrillary tangles are mainly composed of paired helical filaments and straight untwisted filaments; the average width of phosphotungstic acid-stained samples is 19.2 nm and the average twist periodicity is 83.2 nm (Morozova et al. 2013). A similar measurement was obtained from immunogold-labeled AD brain samples in later structural studies (Xu et al. 2020). To characterize the tau filaments extracted from TgTau(P301L)23027 mouse brains, TEM showed three structurally distinct types of tau fibrils—coiled fibrils, straight fibrils, and twisted ribbon-like fibrils (Daude et al. 2020).

With its recent advances, cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) can be considered a revolutionary method to reveal the structure of fibrils with ångström-level resolution. Figure 3 offers a summary of solved tau fibril structures available on the Protein Data Bank. Cryo-EM studies of tau fibrils obtained from brains of human patients with distinct tauopathies (AD, PiD, and CTE) have revealed that each tauopathy has characteristic filament folds, which are conserved among individuals with the same disease, yet different from structures obtained from in vitro aggregation of recombinant tau (Falcon et al. 2018b; Zhang et al. 2019). The first report on cryo-EM structure of pathological tau (with 3.4–3.5 Å resolution) is based on atomic models of paired helical filaments and straight filaments obtained from an individual AD patient. This structure shows that the core of both tau filaments is made of identical protofilaments (residues Val306–Phe378) which adopt a combined cross-β/β-helix structure, and the two types of filaments are ultrastructural polymorphs with differences in their inter-protofilament packing (Fitzpatrick et al. 2017). The ultrastructure of tau filaments obtained from PiD and CTE came along next (with a resolution of 3.2 Å and 2.3 Å, respectively) (Falcon et al. 2018a, 2019). While the filament core in PiD (a 3R tauopathy) consists of residues Lys254–Phe378 of 3R tau, the filaments in CTE entail residues Lys274–Arg379 of 3R and Ser305–Arg379 of 4R tau isoforms (Falcon et al. 2018a, 2019). Recently, the cryo-EM analysis demonstrated the ultrastructure of tau filaments (at 3–3.2 Å resolution) found in two prion-protein amyloidoses: protein cerebral amyloid angiopathy (PrP-CAA) with Q160X mutation on the PRNP gene and Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease (GSS) with F198S mutation on the PRNP gene (Hallinan et al. 2021). Tau filaments found in PrP-CAA are composed of both PHFs and SFs, whereas PHFs appear to be the only constituent of GSS samples. Notably, the atomic models of the tau fibrils extracted from PrP-CAA and GSS are identical to tau filaments found in AD—also a secondary tauopathy—but different from those obtained from Pick’s disease (Hallinan et al. 2021). As more tau filament structures became available (e.g., AGD, PSP, and GGT) (Shi et al. 2021b), a new scheme has been proposed to classify tauopathies according to their characteristic filament folds, complementing neuropathological and clinical profiles with a structural angle.

Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments. a Heparin-induced 2N4R tau snake filament (resolution: 3.30 Å). PDB: 6QJH (Zhang et al. 2019). a’ Heparin-induced 2N4R tau twister filament (resolution: 3.30 Å). PDB: 6QJM (Zhang et al. 2019). a’’ Heparin-induced 2N4R tau jagged filament (resolution: 3.50 Å). PDB: 6QJP (Zhang et al. 2019). a’’’ Heparin-induced 2N3R tau filament (resolution: 3.70 Å). PDB: 6QJQ (Zhang et al. 2019). b PHF from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (sAD, resolution: 3.20 Å). PDB: 6HRE (Falcon et al. 2018b). b’ SF from sAD (resolution: 3.30 Å). 6HRF (Falcon et al. 2018b). b’’ Type 1 tau filament from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE, resolution: 2.30 Å). 6NWP (Falcon et al. 2019). b’’’ Type 2 tau filament from CTE (resolution: 3.40 Å). 6NWQ (Falcon et al. 2019). c Double tau fibril from corticobasal degeneration (CBD, resolution: 3.80 Å). PDB: 6VH7 (Arakhamia et al. 2020). c’ Single tau fibril from CBD (resolution: 4.30 Å). PDB: 6VHA (Arakhamia et al. 2020). c’’ Type 1 tau filament from CBD (resolution: 3.20 Å). PDB: 6TJO (Zhang et al. 2020). c’’’ Type 2 tau filament from CBD (resolution: 3.00 Å). PDB: 6TJX (Zhang et al. 2020). d PHF from primary age-related tauopathy (PART, resolution: 2.76 Å). PDB: 7NRQ (Shi et al. 2021a). d’ SF from PART (resolution: 2.68 Å). PDB: 7NRS (Shi et al. 2021a). d’’ Type 1 tau filament from argyrophilic grain disease (AGD, resolution: 3.30 Å). PDB: 7P6D (Shi et al. 2021b). d’’’ Type 2 tau filament from AGD (resolution: 3.40 Å). PDB: 7P6E (Shi et al. 2021b). e Tau filament from progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP, resolution: 2.70 Å). PDB: 7P65 (Shi et al. 2021b). e’ Type 1a tau filament from limbic-predominant neuronal inclusion body 4R tauopathy (LNT, resolution: 3.40 Å). PDB: 7P6A (Shi et al. 2021b). e’’ Type 2 tau filament from LNT (resolution: 2.50 Å). PDB: 7P6C (Shi et al. 2021b). e’’’ Type 1b tau filament from LNT (resolution: 2.20 Å). PDB: 7P6B (Shi et al. 2021b). f Narrow Pick filament from Pick’s disease (PiD, resolution: 3.20 Å). PDB: 6GX5 (Falcon et al. 2018a). f’ PHF from Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease (GSS, resolution: 3.30 Å). PDB: 7MKH (Hallinan et al. 2021). f’’ PHF from prion protein cerebral amyloid angiopathy (PrP-CAA, resolution: 3.00 Å). PDB: 7MKF (Hallinan et al. 2021). f’’’ SF from PrP-CAA (resolution: 3.07 Å). PDB: 7MKG (Hallinan et al. 2021). Cyan: residues 244–274 (R1); dark purple: residues 275–305 (R2); green: 306–336 (R3); magenta: 337–368 (R4); black: 369–441 (N-terminus). Images are created by the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC.

Despite being a powerful tool, cryo-EM analysis has its own limitations that may result in the omission of tau species critical for pathogenesis and disease progression. Besides technical considerations relating to sampling, several factors need to be examined:

-

1.

Soluble tau oligomers may exist in multiple conformations, but only a subset of these conformations is represented by the structures present in long-lived fibrils.

-

2.

When structurally distinct tau filaments co-exist (e.g., SFs and PHFs), their ratios in each disease may be a crucial, yet under-investigated parameter.

-

3.

PTM patterns could add another level of conformational diversity. As an example, ubiquitination of tau within the fibril-forming core region (Lys369–Glu380) can mediate fibril diversity (Arakhamia et al. 2020).

-

4.

Critical conformational fingerprints may be present in regions of tau beyond the protease-resistant repeat domain core, for example, the fuzzy coat, which remains to be a challenge for current cryo-EM technology.

Tau strains and therapeutic development

Developing effective therapeutic agents against AD and other types of tauopathies has been a chief objective in the field of neurodegeneration. Currently, there are no effective, disease-modifying interventions available other than temporary symptomatic relief, such as using cholinesterase inhibitors to address a cholinergic deficit (Xu et al. 2021), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors to relieve behavioral symptoms (Xie et al. 2019), and employing physical therapy to improve functional abilities (Du et al. 2018). Slow progression in therapeutic development is at least partly owing to the heterogeneity of tauopathies (different types of tauopathies and different neurological manifestations in each subtype) and lack of in vitro and in vivo models that accurately reflect such a clinical and molecular diversity.

As different amyloid-directed treatments have encountered obstacles in clinical trials (Salloway et al. 2014; Knopman et al. 2021), tau-targeted therapies have recently attracted more attention. Vaccine-based immunotherapies and small-molecule aggregation blockers represent two commonly adopted approaches that directly target tau in this drug discovery process, along with indirect strategies that target microtubules or tau-related kinases (Giacomini et al. 2018). As summarized in Table 4, among 27 tau-related therapeutic agents currently in clinical trials (2021), 18 candidates fall into the “active/passive immunotherapy” or “aggregation blocker” categories. However, only five may exhibit conformational specificity against different forms of pathogenic tau. As tau has multifaceted physiological and pathological functions (Wang and Mandelkow 2016), pan-tau manipulation may merely represent a preliminary intervention whereas future conformation-specific treatments may yield desired therapeutic outcomes with higher precision.

Protein conformation is indeed an important factor for establishing effective therapeutic interventions. As mentioned, two complications arose from strain diversity of PrPSc in prion diseases: firstly, an anti-prion compound may only target a narrow range of PrPSc conformers (Kawasaki et al. 2007), and secondly, prion therapeutics may change the pool of PrPSc conformers, leading to drug resistance (Berry et al. 2013). In the search for tau-directed reagents, the lessons about prions must be taken on board as the proportion of different tau strains deserves careful consideration and therapy with multiple anti-tau compounds may be required to stop the spread of misfolded tau.

Outlook: revealing the origin of tau strains

The concept that malformed tau can exist in different strains with different transmission and true breeding qualities has become associated with a corollary that different strain-dependent features drive the phenotypic variations that are scored in the clinic. Yet, despite increasing research on the determinants of tau strain properties, it is still not clear which parameters in lifestyle or cell biology are driving the production of variant forms of misfolded tau in idiopathic and genetic tauopathies. Post-translational modifications may play a role in this process as an acetylation-mimic substitution modulates tau pathology and phosphorylation status (Ajit et al. 2019) but this may not be the whole story.

Further complicating the understanding of tau strains is the dynamic conversion between monomeric and multimeric tau. In the process of misfolding, tau monomers, oligomers, and fibrils represent three stages in the equilibrium of templated conversion (Shammas et al. 2015). Since distinct tau strains associate with diverse downstream effects (aggregation kinetics, cellular internalization, and propagation rates) (Falcon et al. 2015; Karikari et al. 2019), a question arises as to which tau assemblies (monomeric vs multimeric) encode these specific strain properties. To date, much tau strain research has been performed with detergent-insoluble fibrillar tau aggregates (Sanders et al. 2014; Kaufman et al. 2016; Eskandari-Sedighi et al. 2017; Daude et al. 2020). Investigation of multimeric soluble tau species (e.g., tau oligomers) remains a challenge, partially due to their ambiguous definition, their unstable biochemical nature, and limitations of current separation technology. Using chronically infected tau reporter cell lines, it was demonstrated for the first time that seed-competent tauRD-YFP monomers adopt stable infectious conformations (Sharma et al. 2018). However, the notion that monomeric tau forms can template different strains may benefit from wider validation.

While it remains ambiguous how different tau conformers evolve and propagate in the brain, the recent development of high-resolution separation methods and sensitive conformation-dependent biophysical assays may allow for more accurate detection and characterization. Asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation (AF4) has been used to separate aggregated PrP species based on their hydrodynamic radii (Silveira et al. 2006; Eskandari-sedighi et al. 2021). As such, AF4 may be used to tease apart the complexity in multimeric tau of different sizes. Recently, double electron–electron resonance spectroscopy (Fichou et al. 2017) and Raman spectroscopy (Devitt et al. 2021) were used as a conformation-dependent assay to assess protein folding. Their reliability in conformational fingerprinting may effectively complement cryo-EM to probe the structural differences in flexible regions of misfolded tau.

In conclusion, a significant challenge in protein folding diseases is to identify the molecular origin of different conformers and how they evolve in the context of different environments (e.g., in distinct anatomical sections of the brain, in different cell types). In tauopathies, tau strains are defined operationally by an array of clinical observations, neuropathological profiles, and biochemical/biophysical signatures. In the current experimental realm, establishing a correlation between strains that are identified with different parameters remains difficult. Such a challenge may be at least partially attributed to the involvement of 3R/4R isoforms of tau and its unique PTM patterns in each disease. Several major questions remain unanswered. Apart from the differences in host factors, can tau strains offer a complete explanation for clinical heterogeneities? Is the divergent evolution of tau strains the cause of different disease manifestations or the outcome? Can tau conformation alone encode its strain properties or are strain-specific co-factors needed (Chakraborty et al. 2021)? Do different tau strains exhibit different sensitivity to drug treatments? Since it remains obscure how anti-aggregation compounds may shape the properties of pathogenic tau through adaptation, our preliminary understanding in strain-dependent drug-resistance in PrPSc (Kawasaki et al. 2007; Berry et al. 2013; Giles et al. 2017) may shine a light on the development of therapeutics for tauopathies. Although quantitative biochemical assays and biophysical assessment have allowed for in-depth analyses on tau conformers, further work is clearly needed to answer these cardinal questions pertaining to the early events at the headwater of transmissible proteinopathies.

References

Ajit D, Trzeciakiewicz H, Tseng J, Wander CM, Chen Y, Ajit A, King DP, Cohen XTJ (2019) A unique tau conformation generated by an acetylation-mimic substitution modulates P301S-dependent tau pathology and hyperphosphorylation. J Biol Chem 294:16698–16711. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA119.009674

Alam R, Driver D, Wu S, Lozano E, Key SL, Hole JT, Hayashi ML, Lu J (2017) Preclinical characterization of an antibody [Ly3303560] targeting aggregated Tau. Alzheimers Dement 13:5–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2017.07.227

Allen B, Ingram E, Takao M, Smith MJ, Jakes R, Virdee K, Yoshida H, Holzer M, Craxton M, Emson PC, Atzori C, Migheli A, Crowther RA, Ghetti B, Spillantini MG, Goedert M (2002) Abundant tau filaments and neurodegeneration in mice transgenic for human P301S tau. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 22:9340–9351

Anfossi M, Vuono R, Maletta R, Virdee K, Mirabelli M, Colao R, Puccio G, Bernardi L, Frangipane F, Gallo M, Geracitano S, Tomaino C, Curcio SAM, Zannino G, Lamenza F, Duyckaerts C, Spillantini MG, Losso MA, Bruni AC (2011) Compound heterozygosity of 2 novel MAPT mutations in frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging 32:757.e1-757.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.12.013

Arakhamia T, Lee CE, Carlomagno Y, Duong DM, Kundinger SR, Wang K, Williams D, DeTure M, Dickson DW, Cook CN, Seyfried NT, Petrucelli L, Fitzpatrick AWP (2020) Posttranslational modifications mediate the structural diversity of tauopathy strains. Cell 180:633-644.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.027

Arena JD, Smith DH, Lee EB, Gibbons GS, Irwin DJ, Robinson JL, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ, Stewart W, Johnson VE (2020) Tau immunophenotypes in chronic traumatic encephalopathy recapitulate those of ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 143:1572–1587. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa071

Arrasate M, Pérez M, Avila J (2000) Tau dephosphorylation at Tau-1 site correlates with its association to cell membrane. Neurochem Res 25:43–50. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007583214722

Atarashi R, Satoh K, Sano K, Fuse T, Yamaguchi N, Ishibashi D, Matsubara T, Nakagaki T, Yamanaka H, Shirabe S, Yamada M, Mizusawa H, Kitamoto T, Klug G, McGlade A, Collins SJ, Nishida N (2011) Ultrasensitive human prion detection in cerebrospinal fluid by real-time quaking-induced conversion. Nat Med 17:175–178. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2294

Ayalon G, Lee S, Adolfsson O, Foo-atkins C, Atwal JK, Blendstrup M, Booler H, Bravo J, Brendza R, Brunstein F, Chan R, Chandra P, Couch JA, Datwani A, Demeule B, Dicara D, Erickson R, Ernst JA, Foreman O, He D, Hotzel I, Keeley M, Kwok MCM, Lafrance-Vanasse J, Lin H, Lu Y, Luk W, Manser P, Muhs A, Ngu H, Pfeifer A, Pihlgren M, Rao GK, Scearce-Levie K, Schauer SP, Smith WB, Solanoy H, Teng E, Wildsmith KR, Yadav DB, Ying Y, Fuji RN, Kerchner GA (2021) Antibody semorinemab reduces tau pathology in a transgenic mouse model and engages tau in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med 13:eabb2639

Bandyopadhyay B, Li G, Yin H, Kuret J (2007) Tau aggregation and toxicity in a cell culture model of tauopathy. J Biol Chem 282:16454–16464. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M700192200

Bartz JC (2016) Prion strain diversity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 6. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a024349

Basler K, Oesch B, Scott M, Westaway D, Wälchli M, Groth DF, McKinley MP, Prusiner SB, Weissmann C (1986) Scrapie and cellular PrP isoforms are encoded by the same chromosomal gene. Cell 46:417–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(86)90662-8

Berry DB, Lu D, Geva M, Watts JC, Bhardwaj S, Oehler A, Renslo AR, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Giles K (2013) Drug resistance confounding prion therapeutics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1317164110

Bessen RA, Marsh RF (1992) Biochemical and physical properties of the prion protein from two strains of the transmissible mink encephalopathy agent. J Virol 66:2096–2101. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.66.4.2096-2101.1992

Bigio EH, Lipton AM, Yen SH, Hutton ML, Baker M, Nacharaju P, White CL, Davies P, Lin W, Dickson DW (2001) Frontal lobe dementia with novel tauopathy: sporadic multiple system tauopathy with dementia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 60:328–341. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/60.4.328

Bijttebier S, Theunis C, Jahouh F, Rodrigues D, Verhemeldonck M, Grauwen K, Dillen L, Mercken M (2021) Development of immunoprecipitation – two-dimensional liquid chromatography – mass spectrometry methodology as biomarker read-out to quantify phosphorylated tau in cerebrospinal fluid from Alzheimer disease patients. J Chromatogr A 1651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2021.462299

Binder LI, Frankfurter A, Rebhun LI (1985) The distribution of tau in the mammalian central nervous central nervous. J Cell Biol 101:1371–1378. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.101.4.1371

Black MM, Slaughter T, Moshiach S, Obrocka M, Fischer I (1996) Tau is enriched on dynamic microtubules in the distal region of growing axons. J Neurosci 16:3601–3619. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.16-11-03601.1996

Boluda S, Iba M, Zhang B, Raible KM, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ (2015) Differential induction and spread of tau pathology in young PS19 tau transgenic mice following intracerebral injections of pathological tau from Alzheimer’s disease or corticobasal degeneration brains. Acta Neuropathol 129:221–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-014-1373-0

Braak H, Braak E (1995) Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol Aging 16:271–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-002-1380-9

Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82:239–259. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICINIS.2015.10

Bruce ME (1993) Scrapie strain variation and mutation. Br Med Bull 49:822–838. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072649

Caughey B, Raymond GJ (1991) The scrapie-associated form of PrP is made from a cell surface precursor that is both protease- and phospholipase-sensitive. J Biol Chem 266:18217–18223. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(18)55257-1

Chakraborty P, Rivière G, Liu S, Opakua AI De, Hebestreit A, Andreas LB, Vorberg IM, Zweckstetter M (2021) Co-factor-free aggregation of tau into seeding-competent RNA-sequestering amyloid fibrils. Nat Commun 12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24362-8

Chang E, Kim S, Schafer KN, Kuret J (2011) Pseudophosphorylation of tau protein directly modulates its aggregation kinetics. Biochim Biophys Acta - Proteins Proteomics 1814:388–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.10.005

Chatham JC, Blackband SJ (2001) Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and imaging and animal research. ILAR J 42:189–208

Chen D, Drombosky KW, Hou Z, Sari L, Kashmer OM, Ryder BD, Perez VA, Woodard DNR, Lin MM, Diamond MI, Joachimiak LA (2019) Tau local structure shields an amyloid-forming motif and controls aggregation propensity. Nat Commun 10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10355-1

Chen J, Kanai Y, Cowan NJ, Hirokawa N (1992) Projection domains of MAP2 and tau determine spacings between microtubules in dendrites and axons. Nature 360:674–677. https://doi.org/10.1038/360674a0

Chen M, Martins RN, Lardelli M (2009) Complex splicing and neural expression of duplicated tau genes in zebrafish embryos. J Alzheimer’s Dis 18:305–317. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2009-1145

Choi MC, Raviv U, Miller HP, Gaylord MR, Kiris E, Ventimiglia D, Needleman DJ, Kim MW, Wilson L, Feinstein SC, Safinya CR (2009) Human microtubule-associated-protein tau regulates the number of protofilaments in microtubules: a synchrotron X-ray scattering study. Biophys J 97:519–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.047

Clavaguera F, Akatsu H, Fraser G, Crowther RA, Frank S, Hench J, Probst A, Winkler DT, Reichwald J, Staufenbiel M, Ghetti B, Goedert M, Tolnay M (2013) Brain homogenates from human tauopathies induce tau inclusions in mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:9535–9540. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1301175110

Cohen ML, Kim C, Haldiman T, ElHag M, Mehndiratta P, Pichet T, Lissemore F, Shea M, Cohen Y, Chen W, Blevins J, Appleby BS, Surewicz K, Surewicz WK, Sajatovic M, Tatsuoka C, Zhang S, Mayo P, Butkiewicz M, Haines JL, Lerner AJ, Safar JG (2015) Rapidly progressive Alzheimer’s disease features distinct structures of amyloid-β. Brain 138:1009–1022. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv006

Collinge J (2001) Prion diseases of humans and animals: their causes and molecular basis. Annu Rev Neurosci 24:519–550

Collinge J, Clarke AR (2007) A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science (80- ) 318:930–936. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1138718

Collinge J, Sidle KCL, Meads J, Ironside J, Hill AF (1996) Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of “new variant” CJD. Nature 383:685–690. https://doi.org/10.1038/383685a0

Cordeiro TN, Herranz-Trillo F, Urbanek A, Estaña A, Cortés J, Sibille N, Bernadó P (2017) Small-angle scattering studies of intrinsically disordered proteins and their complexes. Curr Opin Struct Biol 42:15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2016.10.011

Coustou V, Deleu C, Saupe S, Begueret J (1997) The protein product of the het-s heterokaryon incompatibility gene of the fungus Podospora anserina behaves as a prion analog. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:9773–9778. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.18.9773

Crick F (1970) Central dogma of molecular biolog. Cent Dogma Mol Biol 227. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6754-9_2672

Daebel V, Chinnathambi S, Biernat J, Schwalbe M, Habenstein B, Loquet A, Akoury E, Tepper K, Müller H, Baldus M, Griesinger C, Zweckstetter M, Mandelkow E, Vijayan V, Lange A (2012) β-sheet core of tau paired helical filaments revealed by solid-state NMR. J Am Chem Soc 134:13982–13989. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja305470p

Daude N, Kim C, Gyun S, Ghazaleh K, Sedighi E, Haldiman T, Yang J, Fleck SC, Gomez E, Zhuang C, Han Z, Borrego S, Serene E (2020) Diverse, evolving conformer populations drive distinct phenotypes in frontotemporal lobar degeneration caused by the same MAPT - P301L mutation. Acta Neuropathol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-020-02148-4

De Calignon A, Polydoro M, Suárez-Calvet M, William C, Adamowicz DH, Kopeikina KJ, Pitstick R, Sahara N, Ashe KH, Carlson GA, Spires-Jones TL, Hyman BT (2012) Propagation of tau pathology in a model of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 73:685–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.033

Devitt G, Crisford A, Rice W, Weismiller HA, Fan Z, Commins C, Hyman BT, Margittai M, Mahajan S, Mudher A (2021) Conformational fingerprinting of tau variants and strains by Raman spectroscopy. RSC Adv 11:8899–8915. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1ra00870f

Dickinson AG, Meikle VMH (1969) A comparison of some biological characteristics of the mouse-passaged scrapie agents, 22A and ME7. Genet Res 13:213–225. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016672300002895

Du Z, Li Y, Li J, Zhou C, Li F, Yang X (2018) Physical activity can improve cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Interv Aging 13:1593–1603. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S169565

Dujardin S, Bégard S, Caillierez R, Lachaud C, Delattre L, Carrier S, Loyens A, Galas MC, Bousset L, Melki R, Aurégan G, Hantraye P, Brouillet E, Buée L, Colin M (2014) Ectosomes: a new mechanism for non-exosomal secretion of Tau protein. PLoS ONE 9:28–31. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100760

Dujardin S, Commins C, Lathuiliere A, Beerepoot P, Fernandes AR, Kamath TV, De Los Santos MB, Klickstein N, Corjuc DL, Corjuc BT, Dooley PM, Viode A, Oakley DH, Moore BD, Mullin K, Jean-Gilles D, Clark R, Atchison K, Moore R, Chibnik LB, Tanzi RE, Frosch MP, Serrano-Pozo A, Elwood F, Steen JA, Kennedy ME, Hyman BT (2020) Tau molecular diversity contributes to clinical heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 26:1256–1263. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0938-9

Elslande V, JVermeersch P, Vandervoort K, Wawina-Bokalanga T, Vanmechelen B, Wollants E, Laenen L, André E, Van Ranst M, Lagrou K, Maes P, (2021) Symptomatic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) reinfection by a phylogenetically distinct strain. Clin Infect Dis 73:354–356. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwaa113

Eskandari-sedighi G, Cortez LM, Yang J, Daude N, Shmeit K, Sim V, Westaway D (2021) Quaternary structure changes for PrP Sc predate PrP C downregulation and neuronal death during progression of experimental scrapie disease. Mol Neurobiol 58:375–390

Eskandari-Sedighi G, Daude N, Gapeshina H, Sanders DW, Kamali-Jamil R, Yang J, Shi B, Wille H, Ghetti B, Diamond MI, Janus C, Westaway D (2017) The CNS in inbred transgenic models of 4-repeat tauopathy develops consistent tau seeding capacity yet focal and diverse patterns of protein deposition. Mol Neurodegener 12:1–27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-017-0215-7

Evans LD, Wassmer T, Fraser G, Smith J, Perkinton M, Billinton A, Livesey FJ (2018) Extracellular monomeric and aggregated tau efficiently enter human neurons through overlapping but distinct pathways. Cell Rep 22:3612–3624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.021

Falcon B, Cavallini A, Angers R, Glover S, Murray TK, Barnham L, Jackson S, Neill MJO, Isaacs AM, Hutton ML, Szekeres PG, Goedert M (2015) Conformation determines the seeding potencies of native and recombinant tau aggregates. J Biol Chem 290:1049–1065. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.589309

Falcon B, Zhang W, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ, Vidal R, Crowther RA, Ghetti B, Scheres SHW, Goedert M (2018a) Structures of filaments from Pick’s disease reveal a novel tau protein fold. Nature 561:137–140. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0454-y

Falcon B, Zhang W, Schweighauser M, Murzin AG, Vidal R, Garringer HJ, Ghetti B, Scheres SHW, Goedert M (2018b) Tau filaments from multiple cases of sporadic and inherited Alzheimer’s disease adopt a common fold. Acta Neuropathol 136:699–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-018-1914-z

Falcon B, Zivanov J, Zhang W, Murzin AG, Garringer HJ, Vidal R, Crowther RA, Newell KL, Ghetti B, Goedert M, Scheres SHW (2019) Novel tau filament fold in chronic traumatic encephalopathy encloses hydrophobic molecules. Nature 568:420–423. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1026-5

Ferrer I, López-González I, Carmona M, Arregui L, Dalfó E, Torrejón-Escribano B, Diehl R, Kovacs GG (2014) Glial and neuronal tau pathology in tauopathies: characterization of disease-specific phenotypes and tau pathology progression. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 73:81–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/NEN.0000000000000030

Fichou Y, Eschmann NA, Keller TJ, Han S (2017) Conformation-based assay of tau protein aggregation, 1st edn. Elsevier Inc

Fiock KL, Smalley ME, Crary JF, Pasca AM, Hefti MM (2020) Increased tau expression correlates with neuronal maturation in the developing human cerebral cortex. eNeuro 7:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0058-20.2020

Fitzpatrick AWP, Falcon B, He S, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ, Crowther RA, Ghetti B, Goedert M, Scheres SHW (2017) Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 547:185–190. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23002

Frappier TF, Georgieff IS, Brown K, Shelanski ML (1994) τ regulation of microtubule-microtubule spacing and bundling. J Neurochem 63:2288–2294. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63062288.x

Fraser H, Dickinson AG (1973) Scrapie in mice. Agent-strain differences in the distribution and intensity of grey matter vacuolation. J Comp Pathol 83:29–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9975(73)90024-8

Frost B, Jacks RL, Diamond MI (2009) Propagation of Tau misfolding from the outside to the inside of a cell. J Biol Chem 284:12845–12852. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M808759200

Funk KE, Mirbaha H, Jiang H, Holtzman DM, Diamond MI (2015) Distinct therapeutic mechanisms of tau antibodies: promoting microglial clearance versus blocking neuronal uptake. J Biol Chem 290:21652–21662. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M115.657924

Giacomini C, Koo CY, Yankova N, Tavares IA, Wray S, Noble W, Hanger DP, Morris JDH (2018) A new TAO kinase inhibitor reduces tau phosphorylation at sites associated with neurodegeneration in human tauopathies. Acta Neuropathol Commun 6:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0539-8

Giles K, Olson SH, Prusiner SB (2017) Developing therapeutics for PrP prion diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 7:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a023747

Glatzel M (2005) Human prion diseases. Arch Neurol 62:545–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374984-0.01213-4

Glover JR, Kowal AS, Schirmer EC, Patino MM, Liu JJ, Lindquist S (1997) Self-seeded fibers formed by Sup35, the protein determinant of [PSI+], a heritable prion-like factor of S. cerevisiae. Cell 89:811–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80264-0

Goedert M, Jakes R (1990) Expression of separate isoforms of human tau protein: correlation with the tau pattern in brain and effects on tubulin polymerization. EMBO J 9:4225–4230. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07870.x

Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA (1989) Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 3:519–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/0896-6273(89)90210-9

Goedert M, Wischik CM, Crowther RA, Walker JE, Klug A (1988) Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding a core protein of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease: identification as the microtubule-associated protein tau. Proc Nati Acad Sci USA 85:4051–4055

Gonzalez C, Armijo E, Bravo-Alegria J, Becerra-Calixto A, Mays CE, Soto C (2018) Modeling amyloid beta and tau pathology in human cerebral organoids. Mol Psychiatry 23:2363–2374. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0229-8

Gorath M, Stahnke T, Mronga T, Goldbaum O, Richter-Landsberg C (2001) Developmental changes of tau protein and mRNA in cultured rat brain oligodendrocytes. Glia 36:89–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/glia.1098

Grover A, England E, Baker M, Sahara N, Adamson J, Granger B, Houlden H, Passant U, Yen SH, DeTure M, Hutton M (2003) A novel tau mutation in exon 9 (1260V) causes a four-repeat tauopathy. Exp Neurol 184:131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00393-5

Guo JL, Narasimhan S, Changolkar L, He Z, Stieber A, Zhang B, Gathagan RJ, Iba M, McBride JD, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY (2016) Unique pathological tau conformers from Alzheimer’s brains transmit tau pathology in nontransgenic mice. J Exp Med 213:2635–2654. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20160833

Guo T, Noble W, Hanger DP (2017) Roles of tau protein in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol 133:665–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-017-1707-9

Haïk S, Brandel JP (2011) Biochemical and strain properties of CJD prions: complexity versus simplicity. J Neurochem 119:251–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07399.x

Hallinan GI, Hoq MR, Ghosh M, Vago FS, Fernandez A, Garringer HJ, Vidal R, Jiang W, Ghetti B (2021) Structure of Tau filaments in prion protein amyloidoses. Acta Neuropathol 142:227–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-021-02336-w

He Z, Mcbride JD, Xu H, Changolkar L, Kim S, Zhang B, Narasimhan S, Gibbons GS, Guo JL, Kozak M, Schellenberg GD, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM (2020) Transmission of tauopathy strains is independent of their isoform composition. Nat Commun 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13787-x

Heinisch JJ, Brandt R (2016) Signaling pathways and posttranslational modifications of tau in Alzheimer’s disease: the humanization of yeast cells. Microb Cell 3:135–146. https://doi.org/10.15698/mic2016.04.489

Hill AF, Desbruslais M, Joiner S, Sidle KCL, Gowland I, Collinge J, Doey LJ, Lantos P (1997) The same prion strain causes vCJD and BSE [10]. Nature 389:448–450. https://doi.org/10.1038/38925

Adolf H (1989) Structure of the Bovine Tau Gene: Alternatively Spliced Transcripts Generate a Protein Family 9:1389–1396

Holmes BB, DeVos SL, Kfoury N, Li M, Jacks R, Yanamandra K, Ouidja MO, Brodsky FM, Marasa J, Bagchi DP, Kotzbauer PT, Miller TM, Papy-Garcia D, Diamond MI (2013) Heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate internalization and propagation of specific proteopathic seeds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1301440110

Holmes BB, Furman JL, Mahan TE, Yamasaki TR, Mirbaha H, Eades WC, Belaygorod L, Cairns NJ, Holtzman DM, Diamond MI (2014) Proteopathic tau seeding predicts tauopathy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E4376–E4385. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1411649111

Huseby CJ, Kuret J (2015) Analyzing Tau aggregation with electron microscopy. Methods Mol Biol 1345:101–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2978-8_7

Hutton M, Lendon C, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering-Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A, Hackett J, Adamson J, Lincoln S, Dickson D, Davies P, Petersen R, Stevens M, de Graaff E, Wauters E, van Baren J, Hillebrand M, Joosse M, Kwon JM, Nowotny P, Che LK, Norton J, Morris JC, Reed LA, Trojanowski J, Basun H, Lannfelt L, Neystat M, Fahn S, Dark F, Tannenberg T, Dodd PR, Hayward N, Kwok JB, Schofield PR, Andreadis A, Snowden J, Craufurd D, Neary D, Owen F, Oostra BA, Hardy J, Goate A, van Swieten J, Mann D, Lynch T, Heutink P (1998) Association of missense and 5’-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 393:702–705

Ikegami S, Harada A, Hirokawa N (2000) Muscle weakness, hyperactivity, and impairment in fear conditioning in tau-deficient mice. Neurosci Lett 279:129–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00964-7

Iqbal K, Del C, Alonso A, Chen S, Chohan MO, El-Akkad E, Gong CX, Khatoon S, Li B, Liu F, Rahman A, Tanimukai H, Grundke-Iqbal I (2005) Tau pathology in Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Basis Dis 1739:198–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.09.008

Ironside JW (2012) Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: an update. Folia Neuropathol 50:50–56