Abstract

Human skin colour is highly heritable and externally visible with relevance in medical, forensic, and anthropological genetics. Although eye and hair colour can already be predicted with high accuracies from small sets of carefully selected DNA markers, knowledge about the genetic predictability of skin colour is limited. Here, we investigate the skin colour predictive value of 77 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from 37 genetic loci previously associated with human pigmentation using 2025 individuals from 31 global populations. We identified a minimal set of 36 highly informative skin colour predictive SNPs and developed a statistical prediction model capable of skin colour prediction on a global scale. Average cross-validated prediction accuracies expressed as area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) ± standard deviation were 0.97 ± 0.02 for Light, 0.83 ± 0.11 for Dark, and 0.96 ± 0.03 for Dark-Black. When using a 5-category, this resulted in 0.74 ± 0.05 for Very Pale, 0.72 ± 0.03 for Pale, 0.73 ± 0.03 for Intermediate, 0.87±0.1 for Dark, and 0.97 ± 0.03 for Dark-Black. A comparative analysis in 194 independent samples from 17 populations demonstrated that our model outperformed a previously proposed 10-SNP-classifier approach with AUCs rising from 0.79 to 0.82 for White, comparable at the intermediate level of 0.63 and 0.62, respectively, and a large increase from 0.64 to 0.92 for Black. Overall, this study demonstrates that the chosen DNA markers and prediction model, particularly the 5-category level; allow skin colour predictions within and between continental regions for the first time, which will serve as a valuable resource for future applications in forensic and anthropologic genetics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Predicting phenotypes from genotypes is a component of complex genetics that has etched its way into many disciplines including personalized medicine, forensic genetics, anthropological genetics, and consumer genetics, depending on the particular phenotype that is predicted from DNA information. The ability to predict human phenotypes with genetic markers has been of continual interest and significant progress has been made, not only in these applied disciplines, but also to more fundamental genetics researchers as it paves the way to find out why certain DNA markers are found to be associated with certain phenotypic traits.

In the case of eye colour, one of the first physical appearance traits to be studied for predictability from DNA, elucidation of its associated DNA markers (Duffy et al. 2007; Eiberg et al. 2008; Frudakis et al. 2003, 2007; Graf et al. 2005; Han et al. 2008; Kanetsky et al. 2002; Kayser et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2010; Posthuma et al. 2006; Rebbeck et al. 2002; Sturm et al. 2008; Sulem et al. 2007, 2008; Zhu et al. 2004), and subsequent step-wise ranking on how suitable they were for phenotype prediction (Liu et al. 2009) led to the introduction, further development, and forensic validation of the IrisPlex system (Chaitanya et al. 2014; Walsh et al. 2011a, b, 2012). It achieved average prediction accuracies, expressed as Area Under the receiver-operating characteristic Curve (AUC), of 0.94 for blue, 0.95 brown, and 0.74 for intermediate (Walsh et al. 2014), and was used in practical applications (Dembinski and Picard 2014; Kastelic et al. 2013; Yun et al. 2014). Moreover, it was demonstrated that for the SNP with the highest prediction rank, rs12913832 from intron 86 of the HERC2 gene, the two alleles act as a molecular switch regulating expression of the nearby OCA2 gene via long-distance enhancer function (Visser et al. 2012).

For human hair colour, gene mapping studies also identified numerous highly associated SNPs (Box et al. 1997; Branicki et al. 2007, 2008a; Fernandez et al. 2008; Flanagan et al. 2000; Graf et al. 2005; Grimes et al. 2001; Han et al. 2008; Harding et al. 2000, 2002, Kanetsky et al. 2004; Mengel-From et al. 2009; Pastorino et al. 2004; Rana et al. 1999; Sulem et al. 2007, 2008; Valenzuela et al. 2010; Valverde et al. 1995; Voisey et al. 2006), 22 of which proved decidedly predictive for hair colour categories (Branicki et al. 2011). From this, and previous eye colour knowledge, the HIrisPlex system was developed and forensically validated for combined eye and hair colour prediction from DNA achieving AUCs of 0.92 for red, 0.85 for black, 0.81 for blond, and 0.75 for brown (Draus-Barini et al. 2013; Walsh et al. 2013, 2014). The HIrisPlex DNA markers and prediction models were used in what has been referred to as the oldest forensic case to date—King Richard III (King et al. 2014) as well as in anthropological estimations of ancestral physical appearance (Cassidy et al. 2016; Gallego-Llorente et al. 2016; Gamba et al. 2014; Jones et al. 2015; Martiniano et al. 2016; Olalde et al. 2015).

Skin coloration, however, is a more difficult physical appearance trait to examine genetically and to elucidate how its associated markers can be ranked for prediction, due to its population specific influence (Jablonski and Chaplin 2000, 2013). The maximal skin colour difference between people from different continents, as a result of environmental adaptation and consequence of the out of Africa migration (Liu et al. 2006), leads to a restriction in gene mapping studies. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) are typically conducted in genetically homogeneous samples to avoid, as much as possible, the false positives that may be produced due to different genetic background between study samples. Therefore, GWASs on skin colour that are performed within continental groups such as Europeans (Han et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2015; Sulem et al. 2008) or South Asians (Edwards et al. 2010; Stokowski et al. 2007) basically identified a list of SNPs explaining subtle skin colour variation within each continental group, but in principle cannot reveal a complete list of skin colour-associated SNPs. Consequently, a previously described prediction model built on exclusively European subjects using SNPs identified in a European skin colour GWAS (Liu et al. 2015) had no power to predict skin colour differences between non-European continents, such as East Asia, Africa, and Native Americans, where considerable skin colour differences exist (Liu et al. 2015). Conversely, previously described skin colour prediction models developed from multi-ethnic data (Maroñas et al. 2014; Valenzuela et al. 2010) had no power to predict skin colour differences within continental groups, such as within Europeans. Noteworthy, a model combining many of these associated SNPs, allowing both DNA-based skin colour prediction within and between continents, has not been described thus far.

The early attempts at predicting skin colour phenotypes from DNA were highly limited in their outcomes (Mushailov et al. 2015; Spichenok et al. 2011; Valenzuela et al. 2010). More recently, Maroñas et al. (2014) published a skin colour prediction study examining 59 pigmentation-associated SNPs in two populations, Africans and Europeans as well as a subset of admixed African-Europeans. Upon training their Bayesian classifier model with a set of 280 individuals, the authors decided on a set of 10 SNPs that together achieved AUC values of 0.999 for white, 0.966 for black, and 0.803 for intermediate skin colour. However, due to the low numbers used in the validation set (n = 118) and the limited populations and individuals studied, it is worthwhile to re-examine these prediction accuracies on a more extensive global scale. Moreover, the previous studies treated Europeans as one group in their prediction analysis (i.e., light skin colour), thereby ignoring the level of skin colour variation from very pale via pale to intermediate that exists among people of European descent.

In an effort to circumvent the current limitations in predicting skin colour from DNA, we tested a large number of SNPs previously associated with human pigmentation traits in a considerable number of individuals from worldwide populations to investigate their skin colour predictive value. As skin colour phenotypes, we used skin types obtained from the Fitzpatrick scale, which is of widespread use in dermatology research and clinical practice. The Fitzpatrick scale groups individuals based on both visually perceived skin colour and skin sensitivity to sun, including tanning ability; the latter being important to differentiate between Europeans of differing light skin tones. We selected a set of the most skin colour informative SNP predictors and built a statistical model for predicting skin colour from DNA on a global scale using 3 and 5 skin colour categories. In addition, we directly compared the prediction outcomes of our newly developed skin colour model with a previously developed model using a separate set of global individuals not previously involved in SNP predictor selection, model building, and model testing.

Materials and methods

Samples and skin colour phenotyping

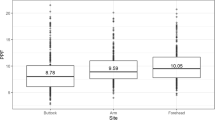

We used 1159 individuals from Southern Poland, 347 individuals from Ireland, 119 from Greece, and 329 individuals living in the USA (parental place of birth for many of these individuals is outside the US; these include Nigeria, Mexico, Argentina, Columbia, India, Bangladesh, Cuba, Palestine, Canada, China, Honduras, Germany, Philippines, Russia, Sudan, Japan, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, El Salvador, Spain, Haiti, South Korea, Vietnam—see online resource information 1). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and was approved by ethical committees of the cooperating institutions. Also included in this study were 71 individuals from the HGDP-CEPH (Rosenberg 2006) set, i.e., from Senegal (n = 21), Nigeria (n = 21), Kenya (n = 11), and Papua New Guinea (n = 17). In total, 2025 individuals were genotyped.

In terms of phenotyping, skin colour classifications followed the Fitzpatrick scale (Fitzpatrick 1988). The scale represents a dermatological assessment to estimate the response of different types of skin to UV light; therefore, it takes into account visual perception of skin colour, as well as tanning ability (Fitzpatrick 1988). It is commonly used by medical practitioners for the classification of a persons skin type, ranging from skin type 1 (pale white skin—no tanning ability), 2 (white skin—minimal tanning ability), 3 (light brown skin—tanning ability), 4 (moderate brown skin—tanning ability), and 5 (dark brown skin—tanning ability) to skin type 6 (deeply pigmented dark brown to black skin)—see online resource information 2. The Polish samples were assessed for their Fitzpatrick skin type by an experienced dermatologist (AB) at sample collection. The Irish, Greek, and US individuals were also assessed by the same dermatologist upon consultation of photographic imagery, and a detailed questionnaire on their ability to tan. Images were taken approximately 20 cm from the forearm of the individual using a Nikon D5300 and R1 ring flash with the following settings: Focus 22, Aperture 1/125, ISO 200. Therefore, all individuals collected were assigned an objective Fitzpatrick scale designation by the same qualified dermatologist avoiding the subjective designations that the volunteers themselves would provide in questionnaire data. For the HGDP-CEPH samples, for which no individual skin colour phenotype information was available, Fitzpatrick scales 6 was assigned as assumed from population knowledge of these African and New Guinean groups, as people living in these geographic regions only have very dark-black skin colour. The 6 Fitzpatrick scales were then re-classified into 5 final skin colour prediction categories for further analyses, i.e., Very Pale (6% of all samples used), Pale (44%), Intermediate (42%), Dark (3%), and Black (5%) by condensing the Fitzpatrick categories 3 and 4 into the Intermediate prediction category and leaving all other categories the same. Categories 3 and 4 of the Fitzpatrick scale are considered very close dermatologically; therefore, it was deemed acceptable to combine these categories for the prediction training of this skin colour model. In a 3-category scale, we grouped Fitzpatrick scale 1–4 Into Light (92%), scale 5 Into Dark (3%), and scale 6 into Dark-Black (5%). Henceforth, the term skin colour category with reference to the categories predicted shall be used for reasons of simplicity in the text; however, it does include not only the visual perception of skin colour but also the ability or lack of to tan. Further information on the Fitzpatrick scale can be found in online resource information 2.

For directly comparing our findings with those from Maroñas et al. (2014), individuals from an independent sample set (n = 194, 17 different populations from Europe, Middle-East, Africa, and Asia) not used in the previous marker ascertainment, model building, or testing, were predicted for skin colour using both models, the one established here, and the one proposed by Maroñas et al. (2014). For this, the same skin colour phenotyping approach as described by Maroñas et al. (2014) was used to make the study outcomes directly comparable. L*ab groups were designated a simple 3-category definition of White, Intermediate, and Black based on groups of L*ab values. The spectrometer values were: L*ab = 74.14–60.36 for White, comprising 132 samples; 59.32–40.04 for Intermediate, comprising 43 samples; 39.75–29.99 for Black, comprising 20 samples.

SNP assessment, genotyping, & statistical analyses

This study examined 2025 individuals for 77 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from 37 genetic loci that were associated with human pigmentation variation, skin colour in particular, in the previous studies (see Table 1 for more details). SNPs were genotyped using SNaPshot (Life Technologies) multiplexes designed and optimized very similar to those described elsewhere (Walsh et al. 2011b, 2013). A subset of 53 SNPs (see Table 1) from 24 genes were selected for further assessment based on their independent contribution (R 2 p value <0.05 uncorrected) towards categorical skin colour prediction, while factoring in sex and population. Finally, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used for determining optimal SNP selection from the 53 SNPs, which resulted in 36 SNPs from 16 genes (SLC24A5 rs1426654, IRF4 rs12203592, MC1R rs1805007, rs1805008, rs11547464, rs885479, rs228479, rs1805006, rs1110400, rs1126809, rs3212355, OCA2 rs1800414, rs1800407, rs12441727, rs1470608, rs1545397 SLC45A2 rs16891982, rs28777, HERC2 rs1667394, rs2238289, rs1129038, rs12913832, rs6497292, TYR rs1042602, rs1393350, RALY rs6059655, DEF8 rs8051733, PIGU rs2378249, ASIP rs6119471, SLC24A4 rs2402130, rs17128291, rs12896399, TYRP1 rs683, KITLG rs12821256, ANKRD11 rs3114908, and BNC2 rs10756819).

After quality control due to some missing genotypes for the full 36 SNP set, Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) modelling was performed for the prediction of categorical skin colour based upon a set of 1423 individuals. Details of the model for the prediction analysis follow studies on eye (Liu et al. 2009; Walsh et al. 2011b) and hair (Branicki et al. 2011; Walsh et al. 2013) colour prediction previously performed. In brief, categorical skin colour, based on five categories (and also three categories), is designated y, and is determined by genotype × (number of minor alleles per k) of k SNPs. For the 5-category designation, π1, π2, π3, π4, and π5 denote the probability of Very Pale, Pale, Intermediate, Dark, and Dark-Black, respectively. To investigate the performance of the 36 skin colour-associated SNPs in a prediction model overall, cross validations were conducted in 1000 randomized replicates; in each replicate, 80% individuals were used as the new training set (n = 1138) and the remaining samples were used as the testing set (n = 285). AUC values were derived from the testing set, and the average AUC values and the standard deviation were reported. AUC values of 0.5 designate a random prediction, whereas values closer to 1 indicate perfect prediction accuracy. Prediction results were produced for five categories as previously named and for three categories; Light (collapsing Very Pale, Pale, and Intermediate), Dark and Dark-Black to illustrate a 3-category grouping. For this study, skin colour prediction probabilities were generated for the test set with the highest probability leading to the most probable prediction for skin colour for each individual.

For comparing our findings with those of Maroñas et al. (2014), an independent set of individuals (n = 194) described as the ‘model comparison set’ were genotyped for the 36 skin colour SNP predictors identified in this study as well as the 10 skin colour SNP predictors proposed by Maroñas et al. (2014) study, allowing a direct comparison of the prediction performance of these two models and their own sets of DNA predictors. For this, the 10 SNPs proposed by Maroñas et al. (2014); KITLG rs10777129, SLC45A2 rs13289 and rs16891982, TYRP1 rs1408799, SLC24A5 rs1426654, OCA2 rs1448484, SLC24A4 rs2402130, TPCN2 rs3829241, ASIP rs6058017, and rs6119471 were genotyped in these 194 samples using SNaPshot (Life Technologies) multiplexing. The Naïve Bayes skin classifier (http://mathgene.usc.es/snipper/skinclassifier.html) was used to predict each individual using the websites requested genotype input. An assessment of the models performance for categorical skin colour prediction was made on the full set of 194 individuals using a confusion matrix of prediction versus observed phenotype, which yielded AUC, Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), and Negative Predictive Value of the model. To directly compare to the performance of the 36 markers proposed by this group, the same individuals were assessed using this study’s proposed 3-category model using the same phenotype scale as recommended by Maroñas et al. (2014). Therefore, the only differing factor was the performance of the Maroñas et al. (2014) skin colour classifier and the 36-marker model proposed in this study for the prediction of categorical skin colour.

All statistical analyses were performed with the R statistics software (R Core Team 2013), using packages MASS (Venables 2002), mlogit (Croissant 2013), ROCR (Sing et al. 2005), pROC (Robin et al. 2011), and caret (Kuhn et al. 2016).

Results and discussion

Selection of skin colour SNP predictors

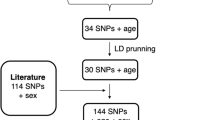

We tested 77 previously pigmentation-associated SNPs from 37 genetic loci (see Table 1 for more information) in 2025 individuals for their value in predicting skin colour from DNA using the Fitzpatrick scale as a phenotype classification system. A partial correlation correcting for sex and population ancestry yielded a subset of 53 SNPs that were statistically significantly associated with the categorical skin colour scale in these individuals (p < 0.05 uncorrected) (see Table 1 for associated SNPs).

Next, model selection was performed on the resulting 53 SNPs using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to estimate the information lost using certain combinations of SNPs, resulting in a balance between goodness of fit for the prediction model and number of SNP inclusions. This approach led to a final set of 36 SNPs from 16 genes (see “Materials and methods”) that were selected for final prediction modelling. Only individuals with a complete list of genotypes for the 36 SNPs could be used for prediction modelling; this led to a decrease in final numbers from 2025 to 1423 individuals.

Prediction modelling of skin colour phenotypes from genotypes

MLR modelling was performed on this 36-SNP set in 1423 individuals using the following categories: Very Pale n = 98, Pale n = 631, Intermediate n = 555, Dark n = 49, and Dark-Black n = 90. To illustrate the breakdown of each SNP’s contribution towards categorical skin colour prediction using 100% of the individuals (n = 1423), each SNP is added sequentially and their collated prediction effect in terms of AUC is estimated, as shown in Fig. 1. To describe the final model chosen, the α and β for each SNP were derived from the full set of 1423 individuals (Male n = 556, Female n = 867; Very Pale n = 98, Pale n = 631, Intermediate n = 555, Dark n = 49, and Dark-Black n = 90) for each skin colour category, and were highlighted for their significant contribution (p value <0.05 uncorrected) towards a certain skin colour category (see Table 2). An illustration of the performance of the chosen 5-category and 3-category model and AUC estimates on the total 100% set can be seen in Fig. 2.

Illustration of the accumulative contribution of each of the selected 36 SNP predictors towards AUC prediction accuracy of 5 skin colour categories based on the full set of 1423 individual. SNP predictors were added to the prediction model one by one in the sequential order from highest to lowest prediction rank. Each colour-coded line represents one of the 5 DNA-predicted skin colour categories. Skin colour phenotyping was via skin types derived from the Fitzpatrick scale

Illustration of the prediction performance of the set of 36 SNPs for the 5-category (a) and the 3-category (b) skin colour prediction model using ROC curves with AUC estimates (including the cross-validated measures) using the full training set of 1423 individuals from 29 populations. Skin colour phenotyping was via skin types derived from the Fitzpatrick scale

However, as the use of 100% of the samples is likely to overestimate the model’s prediction accuracy, the total data set was split 1000 times into 80% training sets (n = 1138) and 20% testing sets (n = 285) and reassessed by performing cross validations (CV). The resulting average AUC values with standard deviation achieved for the different skin colour categories represent the true model performance assessment, and were 0.74 ± 0.05 for Very Pale, 0.72 ± 0.03 for Pale, 0.73 ± 0.03 for Intermediate, 0.87 ± 0.1 for Dark, and 0.97 ± 0.03 for Dark-Black. For the 3-category model, the achieved average AUC values with standard deviation were 0.97 ± 0.02 for Light, 0.83 ± 0.11 for Dark, and 0.96 ± 0.03 for Dark-Black.

Although the lower values in the Very Pale, Pale, and Intermediate categories reflect a dispersal of the Light category into three separate sub-categories, the prediction model factors in this variation to differentiate individuals that display obvious skin colour differences, i.e., very pale skin versus more ‘olive’ tones. Each category provides additional information on the tanning ability of that predicted individual, which is particularly relevant for predicting the variation seen within Europe, especially when comparing northern to southern Europeans. For instance, although they yield lower independent AUC values, taken collectively together in terms of their probability, they provide additional information overall on whether the individual will remain light or pale skinned all year round (as is the case with Pale to Very Pale high probability estimates) or could potentially darken with tanning (representative of high intermediate category probability estimations). In these cases, one must also consider the time of the year (i.e., summer/winter) on whether an individual could potentially appear darker due to sun exposure or remain the same due to lack of sun exposure.

The models established in this study illustrate the reasonably high degree of categorical skin colour prediction accuracy achieved with this set of 36 SNPs from 16 genes. Not only are the models on both a 3 and 5-category level capable of separating light versus dark skin colours between continental groups, but, moreover, the 5-category model also has the ability to separate the subtle variation observed within continental groups, as observed in the Light category expanding to Very Pale, Pale, and Intermediate category predictions.

Comparison with previously reported set of skin colour DNA predictors

To directly compare the skin colour prediction result of our newly established model based on a set of 36 SNPs with that of the 10 SNP set skin classifier previously reported by Maroñas et al. (2014), we genotyped a total of 42 SNPs (4 SNPs overlap between the 36 and the 10 SNPs) in an independent set of 194 samples from individuals living in the US (see online resource information) not previously used in selecting the set of SNP predictors nor for the previous model building and testing. For this analysis, we collected skin colour data from these 194 individuals using a handheld Konica Minolta spectrophotometer CM700d and assigned three skin colour categories White, Intermediate, and Black using CIE L*ab values in the same way as previously described by Maroñas et al. (2014). Of the 194 individuals, 131 (68%) individuals were assigned White, 43 (22%) samples were assigned Intermediate, and 20 (10%) samples were assigned Black. When using the 10 SNP set skin classifier from Maroñas et al. (2014), the achieved AUC values were 0.79 for White, 0.63 for Intermediate, and 0.64 for Black.

However, when using our newly proposed model, an improvement in AUC was observed for White (Light) from 0.79 to 0.82, comparable at the Intermediate (Dark) level, from 0.63 to 0.62, and a large increase for Black (Dark-Black) from 0.64 to 0.92 (see Table 3). It should be mentioned, however, that the improved yet low values for the 36-SNP do not reflect the true performance of the model, as the 36 SNP predictors highlighted in the present study were identified using Fitzpatrick scale phenotypes, not using the phenotype scale previously applied by Maroñas et al. (2014) and what is used in this comparative analysis. If, however, the 194 individuals were assessed according to Fitzpatrick-based skin colour categories, Light, Dark, and Dark-Black accuracy levels increase further to 0.92, 0.74, and 0.94 AUC, respectively (see Table 3). Finally, it is believed that the addition of skin colour specific prediction markers is not solely responsible for the large increase in the Black category prediction between models. The increase could also be inflated by the low numbers of Black individuals used for training of the Bayesian classifier model (n = 22), especially considering their use of prior odds where allele combinations of individuals from a more global ‘Black’ category would not be wholly represented. In any case, these results indicate that our newly proposed model based on a set of 36 skin colour predicting SNPs outperformed the previously proposed model based on a set of 10 SNPs published by Maroñas et al. (2014) regarding prediction accuracy of skin colour from DNA.

Finally, to provide a proof-of-principle on the final markers chosen for a global skin colour prediction model and the data set used to train the model, 14 individuals were selected from the ‘model comparison set’ (not previously involved in modelling), and the 5-category scale skin colour probabilities are shown together with a skin image (Fig. 3). The individuals were chosen to represent different countries around the world where their birth parents were born in and outside the US. It should be noted that considering the highest two categorical probabilities (and not only the highest one) seem to best reflect the colour palette of that particular individual. These preliminary data indicate that the DNA markers and the prediction model we have developed in this study may achieve DNA-based global skin colour prediction regardless of bio-geographic ancestry, which, however, requires further investigation in additional individuals from around the world. In addition, as with all pigmentation traits, a move to a more continuous skin colour prediction would inevitably improve accuracy overall. However, additional global skin colour markers must be unearthed first via large-scale GWAS’s.

Proof-of-principle illustration of the power of the developed model for predicting skin colour on a global scale, regardless of bio-geographic ancestry. Probability outputs from the 5-category skin colour prediction model based on genotypes of the 36 SNP set are shown together with a skin image of the respective DNA donor. Fourteen individuals were chosen from the ‘model comparison set’ based on their parental country of birth, both in and outside the US, representing globally distributed individuals. The order of the images is 1–14 with the following parental birth countries recorded 1-US, 2-US, 3-US, 4-US, 5-Syria, 6-Columbia, 7-China, 8-Vietnam, 9-El Salvador, 10-India, 11-Mexico, 12-Nigeria, 13-Vietnam, 14-Nigeria

The current prediction model is based on multinomial logistic regression, which included a set of carefully selected SNPs. Prediction modeling using alternative approaches, such as the derivation of polygenic scores based on weighted allele sums using an extended list of trait-associated SNPs, may or may not provide higher prediction accuracies as it depends on the number of added SNPs that actually have low to no association/predictive effects. Moreover, the low quality and quantity of DNA typically obtained in applications using DNA-based prediction of visible traits, such as extracts from teeth or bones in anthropological applications and crime scene traces in forensic applications, typically do not allow the analyses of large numbers of SNPs. Therefore, the use of microarray technology is not optimal, and thus, a targeted approach, such as the genotyping of a limited set of DNA markers, recommended here for skin colour prediction, is currently the preferred method of choice.

Conclusions

Overall, we demonstrate that global skin colour, between and within continental groups, can be accurately predicted from DNA using a set of 36 carefully selected SNPs from 16 genes. The DNA markers and the model introduced here deliver prediction accuracies already high enough for practical applications, although for the three different light skin colour categories, they may be further improved with additional (but currently unknown) SNP predictors once identified via future GWAS’s. We envision that if combined with the previously established eye and hair colour predicting SNPs, such as those from the IrisPlex and HIrisPlex systems, all three human pigmentation traits can be reliably predicted from DNA in future forensic and anthropological applications.

References

Box NF, Wyeth JR, O’Gorman LE, Martin NG, Sturm RA (1997) Characterization of melanocyte stimulating hormone receptor variant alleles in twins with red hair. Hum Mol Genet 6:1891–1897

Branicki W, Brudnik U, Kupiec T, Wolanska-Nowak P, Wojas-Pelc A (2007) Determination of phenotype associated SNPs in the MC1R gene. J Forensic Sci 52:349–354

Branicki W, Brudnik U, Draus-Barini J, Kupiec T, Wojas-Pelc A (2008a) Association of the SLC45A2 gene with physiological human hair colour variation. J Hum Genet 53:966–971

Branicki W, Brudnik U, Kupiec T, Wolańska-Nowak P, Szczerbińska A, Wojas-Pelc A (2008b) Association of polymorphic sites in the OCA2 gene with eye colour using the tree scanning method. Ann Hum Genet 72:184–192

Branicki W, Brudnik U, Wojas-Pelc A (2009) Interactions between HERC2, OCA2 and MC1R may influence human pigmentation phenotype. Ann Hum Genet 73:160–170

Branicki W et al (2011) Model-based prediction of human hair color using DNA variants. Hum Genet 129:443–454

Cassidy LM, Martiniano R, Murphy EM, Teasdale MD, Mallory J, Hartwell B, Bradley DG (2016) Neolithic and Bronze Age migration to Ireland and establishment of the insular Atlantic genome. Proceed Nat Acad Sci USA 113:368–373

Chaitanya L et al (2014) Collaborative EDNAP exercise on the IrisPlex system for DNA-based prediction of human eye colour. Foren Sci Int: Genet 11:241–251

Croissant Y (2013) mlogit: multinomial logit model. R Package Version 0.2-4. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mlogit

Dembinski GM, Picard CJ (2014) Evaluation of the IrisPlex DNA-based eye color prediction assay in a United States population. Foren Sci Int: Genet 9:111–117

Donnelly MP et al (2012) A global view of the OCA2-HERC2 region and pigmentation. Hum Genet 131:683–696

Draus-Barini J, Walsh S, Pospiech E, Kupiec T, Glab H, Branicki W, Kayser M (2013) Bona fide colour: DNA prediction of human eye and hair colour from ancient and contemporary skeletal remains. Invest Genet 4:3

Duffy DL et al (2007) A three single-nucleotide polymorphism haplotype in intron 1 of OCA2 explains most human eye-color variation. Am J Hum Genet 80:241–252

Duffy DL, Zhao ZZ, Sturm RA, Hayward NK, Martin NG, Montgomery GW (2010) Multiple pigmentation gene polymorphisms account for a substantial proportion of risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Invest Dermatol 130:520–528

Edwards M et al (2010) Association of the OCA2 polymorphism His615Arg with melanin content in East Asian populations: further evidence of convergent evolution of skin pigmentation. PLoS Genet 6:e1000867

Eiberg H, Troelsen J, Nielsen M, Mikkelsen A, Mengel-From J, Kjaer K, Hansen L (2008) Blue eye color in humans may be caused by a perfectly associated founder mutation in a regulatory element located within the HERC2 gene inhibiting OCA2 expression. Hum Genet 123:177–187

Fernandez LP, Milne RL, Pita G, Aviles JA, Lazaro P, Benitez J, Ribas G (2008) SLC45A2: a novel malignant melanoma-associated gene. Hum Mutat 29:1161–1167

Fitzpatrick TB (1988) The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermat 124:869–871

Flanagan N et al (2000) Pleiotropic effects of the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) gene on human pigmentation. Hum Mol Genet 9:2531–2537

Frudakis T et al (2003) Sequences associated with human iris pigmentation. Genetics 165:2071–2083

Frudakis T, Terravainen T, Thomas M (2007) Multilocus OCA2 genotypes specify human iris colors. Hum Genet 122:311–326

Gallego-Llorente M et al (2016) The genetics of an early Neolithic pastoralist from the Zagros, Iran. Sci Rep 6:31326

Gamba C et al (2014) Genome flux and stasis in a five millennium transect of European prehistory. Nat Commun 5:5257

Graf J, Hodgson R, van Daal A (2005) Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the MATP gene are associated with normal human pigmentation variation. Hum Mutat 25:278–284

Graf J, Voisey J, Hughes I, van Daal A (2007) Promoter polymorphisms in the MATP (SLC45A2) gene are associated with normal human skin color variation. Hum Mutat 28:710–717

Grimes EA, Noake PJ, Dixon L, Urquhart A (2001) Sequence polymorphism in the human melanocortin 1 receptor gene as an indicator of the red hair phenotype. Foren Sci Int 122:124–129

Guenther CA, Tasic B, Luo L, Bedell MA, Kingsley DM (2014) A molecular basis for classic blond hair color in Europeans. Nat Genet 46:748–752

Han J et al (2008) A genome-wide association study identifies novel alleles associated with hair color and skin pigmentation. PLoS Genet 4:e1000074

Harding RM et al (2000) Evidence for variable selective pressures at MC1R. Am J Hum Genet 66:1351–1361

Hart KL, Kimura SL, Mushailov V, Budimlija ZM, Prinz M, Wurmbach E (2013) Improved eye- and skin-color prediction based on 8 SNPs. Croat Med J 54:248–256

Jablonski NG, Chaplin G (2000) The evolution of human skin coloration. J Hum Evol 39:57–106

Jablonski NG, Chaplin G (2013) Epidermal pigmentation in the human lineage is an adaptation to ultraviolet radiation. J Hum Evol 65:671–675

Jacobs LC et al (2015) A genome-wide association study identifies the skin color genes IRF4, MC1R, ASIP, and BNC2 influencing facial pigmented spots. J Invest Dermatol 135:1735–1742

Jin Y et al (2012) Genome-wide association analyses identify 13 new susceptibility loci for generalized vitiligo. Nat Genet 44:676–680

Jones ER et al (2015) Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians. Nat Commun 6:8912

Jonnalagadda M, Norton H, Ozarkar S, Kulkarni S, Ashma R (2016) Association of genetic variants with skin pigmentation phenotype among populations of west Maharashtra, India. Am J Hum Biol 28:610–618

Kanetsky PA, Swoyer J, Panossian S, Holmes R, Guerry D, Rebbeck TR (2002) A polymorphism in the agouti signaling protein gene is associated with human pigmentation. Amer J Hum Genet 70:770–775

Kanetsky PA et al (2004) Assessment of polymorphic variants in the melanocortin-1 receptor gene with cutaneous pigmentation using an evolutionary approach. Canc Epid, Biomark Prevent 13:808–819

Kastelic V, Pośpiech E, Draus-Barini J, Branicki W, Drobnič K (2013) Prediction of eye color in the Slovenian population using the IrisPlex SNPs. Croat Med J 54:381–386

Kayser M et al (2008) Three genome-wide association studies and a linkage analysis identify HERC2 as a human iris color gene. Am J Hum Genet 82:411–423

King TE et al (2014) Identification of the remains of King Richard III. Nat Commun 5:5631

Kuhn M, Wing J, Weston S, Williams A, Keefer C, Engelhardt A, Cooper T, Mayer Z, Kenkel B, the R Core Team, Benesty M, Lescarbeau R, Ziem A, Scrucca L, Tang Y, Candan C, Hunt T (2016) Caret: classification and regression training. R package version 6.0-73, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=caret

Lamason RL et al (2005) SLC24A5, a putative cation exchanger, affects pigmentation in zebrafish and humans. Science 310:1782–1786

Lao O, de Gruijter JM, van Duijn K, Navarro A, Kayser M (2007) Signatures of positive selection in genes associated with human skin pigmentation as revealed from analyses of single nucleotide polymorphisms. Ann Hum Genet 71:354–369

Law MH et al (2015) Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies five new susceptibility loci for cutaneous malignant melanoma. Nat Genet 47:987–995

Liu H, Prugnolle F, Manica A, Balloux F (2006) A geographically explicit genetic model of worldwide human-settlement history. Am J Hum Genet 79:230–237

Liu F, van Duijn K, Vingerling J, Hofman A, Uitterlinden A, Janssens A, Kayser M (2009) Eye color and the prediction of complex phenotypes from genotypes. Curr Biol 19:192–193

Liu F et al (2010) Digital quantification of human eye color highlights genetic association of three new loci. PLoS Genet 6:e1000934

Liu F et al (2015) Genetics of skin color variation in Europeans: genome-wide association studies with functional follow-up. Hum Genet 134:823–835

Maroñas O et al (2014) Development of a forensic skin colour predictive test. Foren Sci Int: Genet 13:34–44

Martiniano R et al (2016) Genomic signals of migration and continuity in Britain before the Anglo-Saxons. Nat Commun 7:10326

Mengel-From J, Wong T, Morling N, Rees J, Jackson I (2009) Genetic determinants of hair and eye colours in the Scottish and Danish populations. BMC Genet 10:88

Mengel-From J, Borsting C, Sanchez JJ, Eiberg H, Morling N (2010) Human eye colour and HERC2, OCA2 and MATP. Foren Sci Int: Genet 4:323–328

Mushailov V, Rodriguez SA, Budimlija ZM, Prinz M, Wurmbach E (2015) Assay development and validation of an 8-SNP multiplex test to predict eye and skin coloration. J Forensic Sci 60:990–1000

Nan H et al (2009) Genome-wide association study of tanning phenotype in a population of European ancestry. J Invest Dermatol 129:2250–2257

Olalde I et al (2015) A common genetic origin for early farmers from mediterranean cardial and central European LBK cultures. Mol Bio Evol 32:3132–3142

Pastorino L et al (2004) Novel MC1R variants in Ligurian melanoma patients and controls. Hum Mutat 24:103

Posthuma D et al (2006) Replicated linkage for eye color on 15q using comparative ratings of sibling pairs. Behav Genet 36:12–17

Praetorius C et al (2013) A polymorphism in IRF4 affects human pigmentation through a tyrosinase-dependent MITF/TFAP2A pathway. Cell 155:1022–1033

Quillen EE et al (2012) OPRM1 and EGFR contribute to skin pigmentation differences between Indigenous Americans and Europeans. Hum Genet 131:1073–1080

R Core Team (2013) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. http://www.R-project.org/

Rana BK et al (1999) High polymorphism at the human melanocortin 1 receptor locus. Genetics 151:1547–1557

Rebbeck TR et al (2002) P gene as an inherited biomarker of human eye color. Canc Epid, Biomark Prev 11:782–784

Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez JC, Müller M (2011) pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform 12:77

Rosenberg NA (2006) Standardized subsets of the HGDP-CEPH human genome diversity cell line panel, accounting for atypical and duplicated samples and pairs of close relatives. Ann Hum Genet 70:841–847

Sing T, Sander O, Beerenwinkel N, Lengauer T (2005) ROCR: visualizing classifier performance in R. Bioinform 21:7881

Spichenok O et al (2011) Prediction of eye and skin color in diverse populations using seven SNPs. Foren Sci Int: Genet 5:472–478

Stokowski RP et al (2007) A genomewide association study of skin pigmentation in a South Asian population. Am J Hum Genet 81:1119–1132

Sturm RA, Larsson M (2009) Genetics of human iris colour and patterns. Pig Cell Melan Res 22:544–562

Sturm RA et al (2003) Genetic association and cellular function of MC1R variant alleles in human pigmentation. Ann New York Acad Sci 994:348–358

Sturm RA et al (2008) A single SNP in an evolutionary conserved region within intron 86 of the HERC2 gene determines human blue-brown eye color. Am J Hum Genet 82:424–431

Sulem P et al (2007) Genetic determinants of hair, eye and skin pigmentation in Europeans. Nat Genet 39:1443–1452

Sulem P et al (2008) Two newly identified genetic determinants of pigmentation in Europeans. Nat Genet 40:835–837

Valenzuela RK et al (2010) Predicting phenotype from genotype: normal pigmentation. J Foren Sci 55:315–322

Valverde P, Healy E, Jackson I, Rees J, Thody A (1995) Variants of the melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor gene are associated with red hair and fair skin in humans. Nat Genet 11:328–330

Venables WN, Ripley BD (2002) Modern applied statistics with S., 4th edn. Springer, New York

Visser M, Kayser M, Palstra RJ (2012) HERC2 rs12913832 modulates human pigmentation by attenuating chromatin-loop formation between a long-range enhancer and the OCA2 promoter. Genome Res 22:446–455

Visser M, Palstra R-J, Kayser M (2014) Human skin color is influenced by an intergenic DNA polymorphism regulating transcription of the nearby BNC2 pigmentation gene. Hum Mol Genet 23:5750–5762

Voisey J, Gomez-Cabrera Mdel C, Smit DJ, Leonard JH, Sturm RA, van Daal A (2006) A polymorphism in the agouti signalling protein (ASIP) is associated with decreased levels of mRNA. Pig cell Res 19:226–231

Walsh S, Lindenbergh A, Zuniga S, Sijen T, de Knijff P, Kayser M, Ballantyne K (2011a) Developmental validation of the IrisPlex system: determination of blue and brown iris colour for forensic intelligence. Foren Sci Int: Genet 5:464–471

Walsh S, Liu F, Ballantyne K, van Oven M, Lao O, Kayser M (2011b) IrisPlex: a sensitive DNA tool for accurate prediction of blue and brown eye colour in the absence of ancestry information. Foren Sci Int: Genet 5:170–180

Walsh S et al (2012) DNA-based eye colour prediction across Europe with the IrisPlex system. Foren Sci Int: Genet 6:330–340

Walsh S et al (2013) The HIrisPlex system for simultaneous prediction of hair and eye colour from DNA. Foren Sci Int: Genet 7:98–115

Walsh S et al (2014) Developmental validation of the HIrisPlex system: dNA-based eye and hair colour prediction for forensic and anthropological usage. Foren Sci Int: Genet 9:150–161

Yun L, Gu Y, Rajeevan H, Kidd KK (2014) Application of six IrisPlex SNPs and comparison of two eye color prediction systems in diverse Eurasia populations. Int J Leg Med 128:447–453

Zhang M et al (2013) Genome-wide association studies identify several new loci associated with pigmentation traits and skin cancer risk in European Americans. Hum Mol Genet 22:2948–2959

Zhu G (2004) A genome scan for eye color in 502 twin families most variation is due to a QTL on chromosome 15q. Twin Res Off J Int Soc Twin Stud 7:197–210

Acknowledgements

The work of SW has funding support from the National Institute of Justice (Grant 2014-DN-BX-K031) and Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI). MK is supported by Erasmus MC. FL is supported by the Erasmus University Rotterdam (EUR) fellowship, and the Thousand Talents Program for Distinguished Young Scholars China. WB, EP, and AB are supported by the Jagiellonian University. We would like to thank all study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00439-017-1817-4.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Walsh, S., Chaitanya, L., Breslin, K. et al. Global skin colour prediction from DNA. Hum Genet 136, 847–863 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-017-1808-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-017-1808-5