Abstract

We recently reported the results of a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of schizophrenia in the Japanese population. In that study, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (rs3106653) in the KCNJ3 (potassium inwardly rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 3) gene located at 2q24.1 showed association with schizophrenia in two independent sample sets. KCNJ3, also termed GIRK1 or Kir3.1, is a member of the G protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channel (GIRK) group. GIRKs are widely distributed in the brain and play an important role in regulating neural excitability through the activation of various G protein-coupled receptors. In this study, we set out to examine this association using a different population. We first performed a gene-centric association study of the KCNJ3 gene, by genotyping 38 tagSNPs in the Chinese population. We detected nine SNPs that displayed significant association with schizophrenia (lowest P = 0.0016 for rs3106658, Global significance = 0.036). The initial marker SNP (rs3106653) examined in our prior GWAS in the Japanese population also showed nominally significant association in the Chinese population (P = 0.028). Next, we analyzed transcript levels in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of postmortem brains from patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and from healthy controls, using real-time quantitative RT-PCR. We found significantly lower KCNJ3 expression in postmortem brains from schizophrenic and bipolar patients compared with controls. These data suggest that the KCNJ3 gene is genetically associated with schizophrenia in Asian populations and add further evidence to the “channelopathy theory of psychiatric illnesses”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a highly heritable neurodevelopmental disorder, with a complex pathophysiology. It is thought that multiple susceptibility genes, each with a small effect, act in conjunction with epigenetic processes and environmental factors. Identifying these susceptibility genes is still challenging and the underlying mechanisms of disease remain largely elusive.

In a search for schizophrenia susceptibility genes, we recently carried out a whole genome association survey and replication study, analyzing two sets of samples from Japanese cohorts. This approach revealed novel candidate genes associated with schizophrenia in the Japanese population (Yamada et al. 2011). Among the top hit signals in the two-stage association analyses, the KCNJ3 gene drew special attention because several other genome-wide association studies (GWASs) (O’Donovan et al. 2009; Tam et al. 2010; Williams et al. 2011) and gene expression studies (Arion and Lewis 2011; Bigos et al. 2010; Huffaker et al. 2009; Kalkman 2011) of schizophrenia and other psychiatric illnesses have revealed a potential role in disease etiology for ion channel genes. Genes for calcium channel [CACNA1C: calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L type, alpha 1C subunit], potassium channels [KCNE1: potassium voltage-gated channel, Isk-related family, member 1, KCNE2: potassium voltage-gated channel, Isk-related family, member 2, KCNH2: potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H (eag-related), member 2] and chloride transporters [NKCC1: sodium/potassium/chloride cotransporter 1, also known as SLC12A2 (solute carrier family 12, member 2), KCC2: potassium/chloride cotransporter 2, also known as SLC12A5 (solute carrier family 12, member 5)] have emerged from these studies. However, the role of the KCNJ3 gene in schizophrenia pathogenesis has not been evaluated so far.

KCNJ3, also known as GIRK1/Kir3.1, belongs to the family of G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK/Kir3) channels. GIRK channels play an important role in controlling neuronal excitability, by generating slow inhibitory potentials, following the activation of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). These GPCRs, are in turn stimulated by various neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, serotonin, opioids and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). The involvement of these neurotransmitters and cognate GPCRs in schizophrenia has been suggested by multiple lines of evidence (Karam et al. 2010). GIRK channels are also implicated in the pathophysiology of several other diseases, such as epilepsy, addiction, Down’s syndrome, ataxia and Parkinson’s disease (Luscher and Slesinger 2010). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that any of these systems related to GIRK channels may contribute to the psychiatric symptoms and cognitive defects seen in schizophrenia.

To corroborate the association of KCNJ3 with schizophrenia in Asian populations, we examined the gene using the following approaches: (1) we performed gene-centric analyses using tag SNPs that span the entire KCNJ3 gene region to achieve greater coverage of genetic variations; (2) we resequenced and analyzed the coding region of the gene; (3) we analyzed patient–parent pedigrees of Chinese descent, an ethnically similar but different population (Kim et al. 2005; Tian et al. 2008); (4) we performed an expression study of the gene using postmortem brains from patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and from controls.

Materials and methods

Samples

Chinese samples consisted of 293 pedigrees (1,163 subjects: 9 trios and 284 quads) collected by the NIMH initiative (http://nimhgenetics.org/).

RNA from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann’s area 46) was obtained from the Stanley Medical Research Institute (http://sncid.stanleyresearch.org/) (Kim and Webster 2009, 2010). Brain samples were taken from 35 schizophrenics (26 males, 9 females; mean ± SD age, 42.6 ± 8.5 years; postmortem interval (PMI), 31.4 ± 15.5 h; brain pH, 6.5 ± 0.2), 35 bipolar disorder patients (17 males, 18 females; mean ± SD age, 45.3 ± 10.5 years; PMI, 37.9 ± 18.3 h; brain pH, 6.4 ± 0.3), and 35 controls (26 males, 9 females; mean ± SD age, 44.2 ± 7.6 years; PMI, 29.4 ± 12.9 h; brain pH, 6.6 ± 0.3). Diagnoses were made in accordance with DSM-IV criteria. There were no significant demographic differences between the schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and control brains, in terms of age, PMI, and sample pH. All the patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder had previously received therapeutic drugs to treat their disease.

Gene-centric association study

SNP information was based on the UCSC database (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). Using ldSelect software (Carlson et al. 2004), tag SNPs were selected according to the following criteria: alleles captured with r 2 ≥ 0.8 and minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 10% in the Han Chinese population. In the gene-centric association study, SNP genotyping was performed using the TaqMan system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s recommendation. PCR was performed using an ABI 9700 thermocycler, and fluorescent signals were analyzed on an ABI 7900HT Fast real-time PCR System using Sequence Detection Software (SDS) v2.3 (Applied Biosystems).

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between markers and departures from the assumption of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) were evaluated based on data from independent parents.

Brain tissue and quantitative RT-PCR

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis was conducted using an ABI7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan probes and primers for KCNJ3 and GAPDH (an internal control) were Assay-on-Demand™ or Assay-by-Design™ gene expression products (Applied Biosystems). All real-time quantitative RT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicate, based on the standard curve method.

Resequencing analysis of KCNJ3

The exons of KCNJ3 were screened for genomic variants by direct sequencing of PCR products, using 58 unrelated Chinese schizophrenia samples. Information on the primers and conditions for amplification are available upon request. Direct sequencing of PCR products was performed using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing FS Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems) and the ABI PRISM 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). SNPs were detected using the SEQUENCHER program (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Statistical analyses

The degree of LD between all SNP markers was evaluated and haplotype structures were constructed using HAPLOVIEW, version 4.2 (Barrett et al. 2005). Single SNP and haplotype association tests were conducted using UNPHASED, version 2.404 (Dudbridge 2008). For multiple testing corrections, the permutations were generated by randomizing the transmission status of the parental haplotypes. In each permutation, the minimum P value was compared to the minimum P value over all the analyses in the original data. This allows for multiple testing corrections over all tests performed in a run (Dudbridge 2008).

The Mann–Whitney U test (two-tailed) was used to evaluate changes in gene expression levels between control and disease groups.

Results

Association study of NIMH Chinese family samples

To examine association of the KCNJ3 gene with schizophrenia in the Chinese population, we performed a family-based association study, by genotyping 293 pedigree samples (284 quad and 9 trio samples, consisting of 1,163 family members) of Chinese origin.

Based on the HapMap database (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), 37 tagSNPs were selected and successfully genotyped in the Chinese pedigree sample (Table 1). The SNP, rs5835552, detected in our mutation screening was also genotyped. Therefore, we analyzed a total of 38 SNPs.

Single marker analysis revealed strong associations for rs3106658 (P = 0.0016) and rs3106651 (P = 0.0019) (Table 1). These SNPs are located in an intronic region approximately 1.7 and 12.4 kb downstream of exon 2 (Fig. 1). The initial marker rs3106653, which showed genetic association with disease in Japanese samples was also significant in the Chinese population (P = 0.029) (Table 1). The remaining six SNPs (rs3111037, rs1823002, rs2652443, rs4567888, rs6713287 and rs 1037091) showed nominally significant allelic association with disease (Table 1). Significant SNPs in the gene showed no deviation from Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium in the samples (independent parents of families).

Genomic structure of KCNJ3 and gene-centric association analysis. In the upper panel, genomic structure and locations of examined tagSNPs in and around KCNJ3 are shown, with chromosomal positions marked according to the human genome database (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) on the top. Gene exons are denoted by boxes. White boxes show non-coding regions. In the lower panel, the negative logarithm of P value for association is plotted as a function of chromosomal positions of SNP markers. Horizontal bold line indicates P value = 0.05 and 0.01

Correction for multiple testing was conducted using the permutation method. This procedure gave a global significance level of P = 0.036 after 10,000 permutations [standard error (SE) = 0.00186].

Analysis of haplotype structures by the confidence interval method (Gabriel et al. 2002) identified eight haplotype blocks in the region (Fig. 2). We performed haplotypic tests for association (Supplementary Table S1). Three of the eight haplotype blocks showed significant association with disease (global P = 0.0067, 0.026 and 0.0386). The two most strongly associated SNPs (rs3106658 and rs3106651) were both located in haplotype block 2, however, most of the other significant SNPs were not in substantial LD to each other.

Haplotype analysis of the KCNJ3 gene. Haplotype structures were constructed using HAPLOVIEW, version 4.2 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/scientific-community/science/programs/medical-and-population-genetics/haploview/haploview). The global significance levels shown, were calculated using PDTPHASE implemented in the UNPHASED program version 2.404 (http://www.mrc-bsu.cam.ac.uk/personal/frank/software/unphased/) (Dudbridge 2008). Values in the box show the squared correlation coefficient (r 2) between the SNPs. Significant SNPs and haplotype blocks are shown in red (P < 0.05). Haplotype blocks 2, 4 and 5 showed significant haplotypic association with schizophrenia

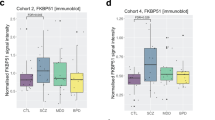

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis in postmortem brains

The identification of KCNJ3 as a susceptibility gene for schizophrenia led us to examine whether there was altered gene expression in the postmortem brains of patients. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR experiments showed that KCNJ3 was down-regulated in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenic and bipolar disorder patients, compared with controls (Fig. 3). To evaluate the effects of medication, Spearman rank-correlation coefficient was used to examine the relation between gene expression levels and a total lifetime exposure to the antipsychotic drug. The transcript levels were not correlated with lifetime use of antipsychotic drugs (P = 0.647 for schizophrenia, P = 0.608 for bipolar disorder patients).

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the KCNJ3 gene in postmortem brains. Rectangles and triangles represent individual samples. Horizontal bars delineate the mean of each group. The expression levels of KCNJ3 were significantly decreased in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of postmortem brains from schizophrenics and bipolar disorder patients, compared with controls

Resequencing of the KCNJ3 gene

To screen for possible functional or causative variants of the KCNJ3 gene, we resequenced all exons using 58 independent samples derived from schizophrenics. We found two novel and five known variants on or close to the upstream and downstream regions of the gene (Supplementary Fig. S1). No nonsynonymous SNPs were detected. Six of seven SNPs showed low allele frequencies (<6.2%) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Given the rarity of these variants, they were excluded from further analysis. The common SNP, rs5835552, was included in the gene-based association study as stated above (not significant).

Discussion

In this study, we conducted a gene-based replication study for a novel candidate gene, KCNJ3 identified from our prior GWAS in Japanese samples (Yamada et al. 2011), using a Han Chinese sample. We genotyped SNPs and resequenced exonic sequences to identify risk variants for schizophrenia. This approach allowed for greater coverage of genetic variations with the additional advantage of narrowing down regions relevant to functional variants, although in this case, we did not identify truly causative SNPs.

Single SNPs and haplotypic analyses have provided genetic evidence for the association of KCNJ3 with schizophrenia in Chinese cohorts. Interestingly, the significant SNP markers and haplotypes were substantially not overlapped. This observation suggests a genetic evidence of allelic heterogeneity for disease risk spanning the KCNJ3 gene. Furthermore, expression levels of KCNJ3 were reduced in the prefrontal cortex of postmortem brains from schizophrenic and bipolar patients. We also performed genotyping of eight SNPs that are on the annotated genes among the top 20 signals (Yamada et al. 2011), however, these SNPs have failed to support association in Chinese population (Supplementary Table S2).

The KCNJ3 gene is a novel candidate in schizophrenia genetics. The gene encodes a G protein-activated, inwardly rectifying potassium channel (GIRK1/Kir3.1) and belongs to the Kir3.x subfamily of inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Inwardly rectifying potassium channels are classified into seven subfamilies (Kir1.x to Kir7.x) and categorized into four functional groups (K+ transport channels, classical Kir channels, G protein-activated K+ channels and ATP-sensitive K+ channels). Four genes, KCNJ3, KCNJ6, KCNJ9 and KCNJ5, are included in the GIRK channel group (also termed GIRK1–GIRK4 or Kir3.1–Kir3.4, respectively) (Hibino et al. 2010). GIRK channels play an important role in maintaining resting membrane potential and regulating the duration of action potentials (Hille 1992).

GIRK1 generally exist as heteromers with other GIRK subunits to form GIRK channels in native cells and tissues. The subunit composition of GIRK channels varies among different cells and tissues, allowing them to play diverse functional roles. In the central nervous system, neuronal GIRK channels are mostly heterotetramers of GIRK1 and GIRK2 subunits (Inanobe et al. 1999; Jelacic et al. 2000; Kofuji et al. 1995; Krapivinsky et al. 1995; Lesage et al. 1995; Liao et al. 1996; Yamada et al. 1998). The activation of GIRK channels by direct binding of the intracellular effector molecules, Gβγ, results in channel opening. This channel opening hyperpolarizes cells, reducing neuronal excitability in many central neurons (Clapham and Neer 1993; Dascal 1997; Jan and Jan 1997; Logothetis et al. 2007; Sadja et al. 2003; Yamada et al. 1998). Many GPCRs in the central nervous system, including the receptors for somatostatin, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HTR1), norepinephrine (ADRA2A, ADRA2B and ADRA2C), μ- (OPRM1), δ-opioid (OPRD1), dopamine (DRD2), glutamate (GRM1 to 8), cannabinoid (CNR1 and CNR2) and GABA (GABBR1 and 2) use signal transduction mechanisms through GIRK channels. These receptors are implicated in a variety of human disorders including schizophrenia (Karam et al. 2010).

These channels may contribute to a range of behaviors, anxiety, spasticity, pain and reward. GIRK1 and 2 knockout mice (GIRK1−/−/GIRK2−/−) are viable and appear normal, but they exhibit thermal hyperalgesia in the tail-flick test and display decreased analgesic responses, following intrathecal administration of morphine (Marker et al. 2004). In addition, GIRK1−/− mice display elevated open-field activity, decreased anxiety-like behavior, decreased baclofen ataxia and increased operant responding for food (Pravetoni and Wickman 2008).

Synaptic N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation in cultured hippocampal neurons increases surface expression of GIRK1 and GIRK2 subunits in the soma, dendrites, and dendritic spines (Chung et al. 2009a, b). Conversely, NMDA receptor antagonists inhibit GIRK complex formation (Kobayashi et al. 2006). In this study, real-time quantitative RT-PCR experiments showed that KCNJ3 is down-regulated in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenic patients. This finding may lend support to the “hypo-NMDA theory of schizophrenia”. Recent studies suggest a genetic association between neuregulin-erbB receptor signaling and schizophrenia (Pitcher et al. 2011; Stefansson et al. 2002), and a functional link between neuregulin-erbB receptor signaling and GIRK is also reported (Ford et al. 2003).

Genetic studies raise the possibility that schizophrenia shares genetic risk factors with other psychiatric disorders (Cascella et al. 2009; Crespi et al. 2010; Rzhetsky et al. 2007). In this study, decreased gene expression was observed in the brains from bipolar disorder, as well as schizophrenia patients. For mood disorders, chronic administration of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, fluoxetine, exerts a beneficial effect on a rodent model of depression, through suppression of GIRK-dependent signaling (Cornelisse et al. 2007). In addition, acute inhibition of GIRK channels by fluoxetine causes substantial suppression of neuronal cell death in mice with mutant GIRK channels (Takahashi et al. 2006). Interestingly, the KCNJ3 gene lies in one of only two regions to have achieved genome-wide significance for linkage in autism (Consortium IMGSoA 2001). Recently, molecular cytogenetic characterization of two unrelated patients with 2q deletions, both of whom are affected by developmental delays with communication impairment, and one of whom has a diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder, revealed that KCNJ3 is the only gene located within the overlapping region of the two deletions (Newbury et al. 2009). In epilepsy, SNP, rs17642086 (1038T>C, His346His) in KCNJ3 shows positive association with idiopathic generalized epilepsy (P = 0.0097) (Chioza et al. 2002). However, this SNP was in weak LD with our significant SNPs on KCNJ3, and we found no genetic association between this SNP and our schizophrenia samples (P = 0.816).

Copy number variants (CNVs) are emerging as an important genomic cause of neuropsychiatric disorders (Coyle 2009). In addition, altered microRNA (miRNA) expression profiles are suggested in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia (Merikangas et al. 2009; Stankiewicz and Lupski 2010). The region does not contain any known CNVs according to a database (Database of Genomic Variants: http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/). By contrast, five conserved sites for miRNA families are detected by the TagetScanHuman (Release 5.2: June 2011, http://www.targetscan.org/) and there are 131 potential miRNA target sites in the gene region (miRNAMAP: http://mirnamap.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/). Therefore, the roles of miRNAs in the gene expression levels need further scrutiny.

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that KCNJ3 contributes to schizophrenia in Asian populations, adding another susceptibility candidate gene to the “channelopathy theory of psychiatric illnesses”. Our findings suggest a significant but a modest association between schizophrenia and the KCNJ3 gene. Thus, future studies with a much larger sample size in Asian and/or in other ethnicities are needed to confirm the genetic contribution of the gene for schizophrenia. Moreover, genetic studies on channel genes including genes in potassium channels are warranted to improve the understanding of schizophrenia pathogenesis.

Abbreviations

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- KCNJ3:

-

Potassium inwardly rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 3

- GIRK:

-

G protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channel

- GPCRs:

-

G protein-coupled receptors

- GABA:

-

γ-Aminobutyric acid

- PMI:

-

Postmortem interval

- LD:

-

Linkage disequilibrium

- HWE:

-

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- SE:

-

Standard error

- NMDA:

-

N-methyl-d-aspartate

References

Arion D, Lewis DA (2011) Altered expression of regulators of the cortical chloride transporters NKCC1 and KCC2 in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68:21–31. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.114

Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ (2005) Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21:263–265

Bigos KL, Mattay VS, Callicott JH, Straub RE, Vakkalanka R, Kolachana B, Hyde TM, Lipska BK, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR (2010) Genetic variation in CACNA1C affects brain circuitries related to mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67:939–945. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.96

Carlson CS, Eberle MA, Rieder MJ, Yi Q, Kruglyak L, Nickerson DA (2004) Selecting a maximally informative set of single-nucleotide polymorphisms for association analyses using linkage disequilibrium. Am J Hum Genet 74:106–120. doi:10.1086/381000

Cascella NG, Schretlen DJ, Sawa A (2009) Schizophrenia and epilepsy: is there a shared susceptibility? Neurosci Res 63:227–235

Chioza B, Osei-Lah A, Wilkie H, Nashef L, McCormick D, Asherson P, Makoff AJ (2002) Suggestive evidence for association of two potassium channel genes with different idiopathic generalised epilepsy syndromes. Epilepsy Res 52:107–116

Chung HJ, Ge WP, Qian X, Wiser O, Jan YN, Jan LY (2009a) G protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium channels mediate depotentiation of long-term potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:635–640

Chung HJ, Qian X, Ehlers M, Jan YN, Jan LY (2009b) Neuronal activity regulates phosphorylation-dependent surface delivery of G protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:629–634

Clapham DE, Neer EJ (1993) New roles for G-protein beta gamma-dimers in transmembrane signalling. Nature 365:403–406

Consortium IMGSoA (2001) A genomewide screen for autism: strong evidence for linkage to chromosomes 2q, 7q, and 16p. Am J Hum Genet 69:570–581

Cornelisse LN, Van der Harst JE, Lodder JC, Baarendse PJ, Timmerman AJ, Mansvelder HD, Spruijt BM, Brussaard AB (2007) Reduced 5-HT1A- and GABAB receptor function in dorsal raphe neurons upon chronic fluoxetine treatment of socially stressed rats. J Neurophysiol 98:196–204

Coyle JT (2009) MicroRNAs suggest a new mechanism for altered brain gene expression in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:2975–2976. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813321106

Crespi B, Stead P, Elliot M (2010) Evolution in health and medicine Sackler colloquium: Comparative genomics of autism and schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(Suppl 1):1736–1741

Dascal N (1997) Signalling via the G protein-activated K+ channels. Cell Signal 9:551–573

Dudbridge F (2008) Likelihood-based association analysis for nuclear families and unrelated subjects with missing genotype data. Human Hered 66:87–98. doi:10.1159/000119108

Ford BD, Liu Y, Mann MA, Krauss R, Phillips K, Gan L, Fischbach GD (2003) Neuregulin-1 suppresses muscarinic receptor expression and acetylcholine-activated muscarinic K+ channels in cardiac myocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 308:23–28

Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, Higgins J, DeFelice M, Lochner A, Faggart M, Liu-Cordero SN, Rotimi C, Adeyemo A, Cooper R, Ward R, Lander ES, Daly MJ, Altshuler D (2002) The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science 296:2225–2229. doi:10.1126/science.1069424

Hibino H, Inanobe A, Furutani K, Murakami S, Findlay I, Kurachi Y (2010) Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol Rev 90:291–366

Hille B (1992) G protein-coupled mechanisms and nervous signaling. Neuron 9:187–195

Huffaker SJ, Chen J, Nicodemus KK, Sambataro F, Yang F, Mattay V, Lipska BK, Hyde TM, Song J, Rujescu D, Giegling I, Mayilyan K, Proust MJ, Soghoyan A, Caforio G, Callicott JH, Bertolino A, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Chang J, Ji Y, Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Kleinman JE, Lu B, Weinberger DR (2009) A primate-specific, brain isoform of KCNH2 affects cortical physiology, cognition, neuronal repolarization and risk of schizophrenia. Nat Med 15:509–518

Inanobe A, Yoshimoto Y, Horio Y, Morishige KI, Hibino H, Matsumoto S, Tokunaga Y, Maeda T, Hata Y, Takai Y, Kurachi Y (1999) Characterization of G-protein-gated K+ channels composed of Kir3.2 subunits in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra. J Neurosci 19:1006–1017

Jan LY, Jan YN (1997) Voltage-gated and inwardly rectifying potassium channels. J Physiol 505(Pt 2):267–282

Jelacic TM, Kennedy ME, Wickman K, Clapham DE (2000) Functional and biochemical evidence for G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels composed of GIRK2 and GIRK3. J Biol Chem 275:36211–36216

Kalkman HO (2011) Alterations in the expression of neuronal chloride transporters may contribute to schizophrenia. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 35:410–414. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.01.004

Karam CS, Ballon JS, Bivens NM, Freyberg Z, Girgis RR, Lizardi-Ortiz JE, Markx S, Lieberman JA, Javitch JA (2010) Signaling pathways in schizophrenia: emerging targets and therapeutic strategies. Trends Pharmacol Sci 31:381–390. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2010.05.004

Kim S, Webster MJ (2009) Postmortem brain tissue for drug discovery in psychiatric research. Schizophr Bull 35:1031–1033. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp106

Kim S, Webster MJ (2010) The stanley neuropathology consortium integrative database: a novel, web-based tool for exploring neuropathological markers in psychiatric disorders and the biological processes associated with abnormalities of those markers. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:473–482. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.151

Kim JJ, Verdu P, Pakstis AJ, Speed WC, Kidd JR, Kidd KK (2005) Use of autosomal loci for clustering individuals and populations of East Asian origin. Human Genet 117:511–519. doi:10.1007/s00439-005-1334-8

Kobayashi T, Washiyama K, Ikeda K (2006) Inhibition of G protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels by ifenprodil. Neuropsychopharmacology 31:516–524

Kofuji P, Davidson N, Lester HA (1995) Evidence that neuronal G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels are activated by G beta gamma subunits and function as heteromultimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:6542–6546

Krapivinsky G, Gordon EA, Wickman K, Velimirovic B, Krapivinsky L, Clapham DE (1995) The G-protein-gated atrial K+ channel IKACh is a heteromultimer of two inwardly rectifying K(+)-channel proteins. Nature 374:135–141

Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Duprat F, Heurteaux C, Fosset M, Romey G, Barhanin J, Lazdunski M (1995) Molecular properties of neuronal G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. J Biol Chem 270:28660–28667

Liao YJ, Jan YN, Jan LY (1996) Heteromultimerization of G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channel proteins GIRK1 and GIRK2 and their altered expression in weaver brain. J Neurosci 16:7137–7150

Logothetis DE, Lupyan D, Rosenhouse-Dantsker A (2007) Diverse Kir modulators act in close proximity to residues implicated in phosphoinositide binding. J Physiol 582:953–965

Luscher C, Slesinger PA (2010) Emerging roles for G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 11:301–315. doi:10.1038/nrn2834

Marker CL, Stoffel M, Wickman K (2004) Spinal G-protein-gated K+ channels formed by GIRK1 and GIRK2 subunits modulate thermal nociception and contribute to morphine analgesia. J Neurosci 24:2806–2812

Merikangas AK, Corvin AP, Gallagher L (2009) Copy-number variants in neurodevelopmental disorders: promises and challenges. Trends Genet 25:536–544. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2009.10.006

Newbury DF, Warburton PC, Wilson N, Bacchelli E, Carone S, Lamb JA, Maestrini E, Volpi EV, Mohammed S, Baird G, Monaco AP (2009) Mapping of partially overlapping de novo deletions across an autism susceptibility region (AUTS5) in two unrelated individuals affected by developmental delays with communication impairment. Am J Med Genet A 149A:588–597

O’Donovan MC, Craddock NJ, Owen MJ (2009) Genetics of psychosis; insights from views across the genome. Hum Genet 126:3–12

Pitcher GM, Kalia LV, Ng D, Goodfellow NM, Yee KT, Lambe EK, Salter MW (2011) Schizophrenia susceptibility pathway neuregulin 1-ErbB4 suppresses Src upregulation of NMDA receptors. Nat Med 17:470–478. doi:10.1038/nm.2315

Pravetoni M, Wickman K (2008) Behavioral characterization of mice lacking GIRK/Kir3 channel subunits. Genes Brain Behav 7:523–531

Rzhetsky A, Wajngurt D, Park N, Zheng T (2007) Probing genetic overlap among complex human phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:11694–11699

Sadja R, Alagem N, Reuveny E (2003) Gating of GIRK channels: details of an intricate, membrane-delimited signaling complex. Neuron 39:9–12

Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR (2010) Structural variation in the human genome and its role in disease. Annu Rev Med 61:437–455. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-100708-204735

Stefansson H, Sigurdsson E, Steinthorsdottir V, Bjornsdottir S, Sigmundsson T, Ghosh S, Brynjolfsson J, Gunnarsdottir S, Ivarsson O, Chou TT, Hjaltason O, Birgisdottir B, Jonsson H, Gudnadottir VG, Gudmundsdottir E, Bjornsson A, Ingvarsson B, Ingason A, Sigfusson S, Hardardottir H, Harvey RP, Lai D, Zhou M, Brunner D, Mutel V, Gonzalo A, Lemke G, Sainz J, Johannesson G, Andresson T, Gudbjartsson D, Manolescu A, Frigge ML, Gurney ME, Kong A, Gulcher JR, Petursson H, Stefansson K (2002) Neuregulin 1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet 71:877–892. doi:10.1086/342734

Takahashi T, Kobayashi T, Ozaki M, Takamatsu Y, Ogai Y, Ohta M, Yamamoto H, Ikeda K (2006) G protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channel inhibition and rescue of weaver mouse motor functions by antidepressants. Neurosci Res 54:104–111

Tam GW, van de Lagemaat LN, Redon R, Strathdee KE, Croning MD, Malloy MP, Muir WJ, Pickard BS, Deary IJ, Blackwood DH, Carter NP, Grant SG (2010) Confirmed rare copy number variants implicate novel genes in schizophrenia. Biochem Soc Trans 38:445–451. doi:10.1042/BST0380445

Tian C, Kosoy R, Lee A, Ransom M, Belmont JW, Gregersen PK, Seldin MF (2008) Analysis of East Asia genetic substructure using genome-wide SNP arrays. PLoS One 3:e3862. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003862

Williams HJ, Craddock N, Russo G, Hamshere ML, Moskvina V, Dwyer S, Smith RL, Green E, Grozeva D, Holmans P, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC (2011) Most genome-wide significant susceptibility loci for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder reported to date cross-traditional diagnostic boundaries. Hum Mol Genet 20:387–391. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq471

Yamada M, Inanobe A, Kurachi Y (1998) G protein regulation of potassium ion channels. Pharmacol Rev 50:723–760

Yamada K, Iwayama Y, Hattori E, Iwamoto K, Toyota T, Ohnishi T, Ohba H, Maekawa M, Kato T, Yoshikawa T (2011) Genome-wide association study of schizophrenia in Japanese population. PLoS One 6:e20468. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020468

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and volunteers who contributed to this study. We also thank Dr. Eiji Hattori for his help in statistical analyses. This work was supported by RIKEN BSI Funds and grants from the Japan Science and Technology Agency, Japan. Additionally, a part of this study is the result of ‘Development of biomarker candidates for social behavior’ carried out under the Strategic Research Program for Brain Sciences of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan.

Data and biomaterials of NIMH samples were collected in projects that participated in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Schizophrenia Genetics Initiative. From 1991 to 1997, the Principal Investigators and Co-Investigators were: Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA, U01 MH46318, Ming T. Tsuang, M.D., Ph.D., D.Sc., Stephen Faraone, Ph.D., and John Pepple, Ph.D.; Washington University, St. Louis, MO, U01 MH46276, C. Robert Cloninger, M.D., Theodore Reich, M.D., and Dragan Svrakic, M.D.; Columbia University, New York, NY U01 MH46289, Charles Kaufmann, M.D., Dolores Malaspina, M.D., and Jill Harkavy Friedman, Ph.D. The data from the Han Chinese Schizophrenia Linkage Study were collected with funding from grant R01 MH59624 from the US National Institute of Mental Health to Ming T. Tsuang, M.D., Ph.D. (Principal Investigator). Other participants in the US were Stephen V. Faraone, Ph.D. (Co-Principal Investigator), Shao Zhu, M.D. (Project Coordinator) and Xingjia Cui, M.D. (Project Coordinator). The project leaders in Taiwan were Hai-Gwo Hwu, M.D. (Taiwan Principal Investigator, National Taiwan University Hospital), Wei J. Chen, M.D. Sci.D. (Taiwan Co- Principal Investigator). Other participants in Taiwan were: Chih-Min Liu, M.D., Shih-Kai Liu, M.D., Ming-Hsien Shieh, M.D., Tzung-Jeng Hwang, M.D., M.P.H., Ming–Ming Tsuang, M.D., Wen Chen OuYang, M.D., Ph.D., Chun-Ying Chen, M.D., Chwen-Cheng Chen, M.D., Ph.D., Jin-Jia Lin, M.D., Frank Huang-Chih Chou, M.D., Ph.D., Ching-Mo Chueh, M.D., Wei-Ming Liu, M.D., Chiao-Chicy Chen, M.D., Jia-Jiu Lo, M.D., Jia-Fu Lee, M.D., Ph.D. Seng Shen, M.D., Yung Feng, M.D., Shin-Pin Lin, M.D, Shi-Chin Guo, M.D, Ming-Cheng Kuo, M.D., Liang-Jen Chuo, M.D., Chih-Pin Lu, M.D., Deng-Yi Chen, M.D., Huan-Kwang Ferng, M.D., Nan-Ying Chiu, M.D., Wen-Kun Chen, M.D., Tien-Cheng Lee, M.D., Hsin-Pei Tang, M.D., Yih-Dar Lee, M.D., Wu-Shih Wang, M.D., For-Wey Long, M.D., Ph.D., Tiao-Lai Huang, M.D., Jung-Kwang Wen, M.D., Cheng- Sheng Chen, M.D., Wen-Hsiang Huang, M.D., Shu-Yu Yang, M.D., Mei-Hua Hall, Cheng-Hsing Chen, M.D. The project leaders in the People’s Republic of China were Xiaogang Chen, M.D., Ph.D. (China Principal Investigator, Institute of Mental Heath, Xiang-ya Teaching Hospital, Central South University), and Xingqun Ni, M.D. (Original Principal Investigator, Sun Yat-sen University). Other participants in China were: Liwen Tan, M.D., Ph.D, Liang Zhou, M.D., Ph.D, Jiajun Shi, M.D., Ph.D, Xiaoling He, M.D., Ph.D, Xiogzhao Zhu, M.D., Ph.D, Lingjian Li, M.D., Ph.D, Ming Wang, M.D., Tiansheng Guo, M.D., Xiaqi Shen, M.D., Ph.D., Jinghua Yang, M.D. ENH/Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, MH059571, Pablo V. Gejman, M.D. (Collaboration Coordinator; PI), Alan R. Sanders, M.D.; Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, MH59587, Farooq Amin, M.D. (PI); University of California, San Francisco, CA, MH60870, William Byerley, M.D. (PI); University of Iowa, Iowa, IA, MH59566, Raymond Crowe, M.D. (PI), Donald Black, M.D.; Washington University, St. Louis, MO, U01, MH060879, C. Robert Cloninger, M.D. (PI); University of Colorado, Denver, CO, MH059565, Robert Freedman, M.D. (PI), Ann Olincy, M.D.; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, MH061675, Douglas Levinson, M.D. (PI), Nancy Buccola, APRN, B.C., M.S.N., New Orleans, Louisiana; University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia, MH059588, Bryan Mowry, M.D. (PI); Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, MH059586, Jeremy Silverman, Ph.D. (PI).

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig. S1

Resequencing analysis of the KCNJ3 gene. Gene exons are denoted by boxes. White boxes show non-coding regions. Novel SNPs found in this study are shown with an asterisk. (EPS 941 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamada, K., Iwayama, Y., Toyota, T. et al. Association study of the KCNJ3 gene as a susceptibility candidate for schizophrenia in the Chinese population. Hum Genet 131, 443–451 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-011-1089-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-011-1089-3