Abstract

In late 2010, an outbreak of Cryptosporidium hominis affected 27,000 inhabitants (45%) of Östersund, Sweden. Previous research shows that abdomen and joint symptoms commonly persist up to 5 years post-infection. It is unknown whether Cryptosporidium is associated with sequelae for a longer duration, how persisting symptoms present over time, and whether sequelae are associated with prolonged infection. In this prospective cohort study, a randomly selected cohort in Östersund was surveyed about cryptosporidiosis symptoms in 2011 (response rate 69.2%). A case was defined as a respondent reporting new diarrhoea episodes during the outbreak. Follow-up questionnaires were sent after 5 and 10 years. Logistic regressions were used to examine associations between case status and symptoms reported after 10 years, with results presented as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals. Consistency of symptoms and associations with case status and number of days with symptoms during outbreak were analysed using X2 and Mann–Whitney U tests. The response rate after 10 years was 74% (n = 538). Case status was associated with reporting symptoms, with aOR of ~3 for abdominal symptoms and ~2 for joint symptoms. Cases were more likely to report consistent symptoms. Cases with consistent abdominal symptoms at follow-up reported 9.2 days with symptoms during the outbreak (SD 8.1), compared to 6.6 days (SD 6.1) for cases reporting varying or no symptoms (p = 0.003). We conclude that cryptosporidiosis was associated with an up to threefold risk for reporting symptoms 10 years post-infection. Consistent symptoms were associated with prolonged infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Cryptosporidium is a protozoan that causes diarrhoea among humans and animals (Pogreba-Brown et al. 2020). Over 90% of human cases are caused by the species Cryptosporidium hominis and C. parvum, usually following intake of contaminated water or food or sometimes through direct contact with an infected individual or animal (Bouzid et al. 2013; Chalmers and Davies 2010; Feng et al. 2018). Infection usually causes diarrhoea, abdominal pain, vomiting, and/or fever but can sometimes be asymptomatic. Cryptosporidiosis is self-limiting in immunocompetent individuals but can sometimes be prolonged (≥7 days) or persistent (≥15 days), with diarrhoea lasting up to 3 weeks (Chalmers and Davies 2010; Checkley et al. 2015). Recurrence of gastrointestinal symptoms after several asymptomatic days is common, even in immunocompetent individuals (Hunter et al. 2004; MacKenzie et al. 1995).

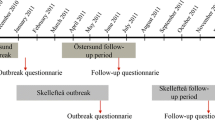

Despite being a common cause of diarrhoea worldwide, only a few large Cryptosporidium outbreaks have been reported in the literature (Efstratiou et al. 2017; MacKenzie et al. 1995; Widerström et al. 2014). In November 2010, the city of Östersund, Sweden, was affected by an outbreak of C. hominis IbA10G2 due to contamination of the public water supply. An estimated 27,000 individuals, constituting approximately 45% of the city’s population, reported symptoms of cryptosporidiosis (Widerström et al. 2014).

After gastroenteritis, sequelae are common and can include post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS), reactive arthritis, and joint pain (Pogreba-Brown et al. 2020). PI-IBS development is considered to be multifactorial: altered signalling by the gut–brain axis, dysbiosis in the intestinal flora, abnormal visceral pain signalling, and intestinal immune activation are contributing factors (Aguilera-Lizarraga et al. 2022). Younger individuals, women, and persons with severe enteritis are more likely to develop PI-IBS (Berumen et al. 2021a). Regarding IBS in general, the presence of anxiety and depression are known to double the risk of experiencing and maintaining symptoms (Sibelli et al. 2016).

Several microorganisms, including the most common gastroenteritis-causing bacteria, and parasites such as Amoeba spp. and Toxoplasma gondii, are also associated with an increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Axelrad et al. 2020). After the Cryptosporidium outbreak in 2010, an increase of late-onset IBD and microscopic colitis was noted in Östersund (Boks et al. 2022).

Persisting sequelae after Cryptosporidium infections are common and may include diarrhoea, abdominal pain, fatigue, and headache (Carter et al. 2020; Carter et al. 2019; Hunter et al. 2004; Iglói et al. 2018). We previously reported that individuals from Östersund, who reported cryptosporidiosis symptoms, were more commonly affected by abdominal symptoms, fatigue, headache, and joint-related symptoms up to 5 years after the outbreak (Lilja et al. 2018; Sjöström et al. 2022). There is a lack of studies regarding the existence of sequelae more than 5 years after the initial infection. Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to evaluate whether post-infectious symptoms persisted at 10 years after Cryptosporidium infection and, if so, how they presented over time. Our secondary aims were to investigate whether long-term persisting symptoms were associated with the duration of the primary infection and whether persistent symptoms were related to self-reported health concerns at the time of the outbreak.

Methods

We performed a prospective cohort study, with follow-up of adult inhabitants of Östersund after the C. hominis outbreak in November 2010.

Study population and data collection

In January 2011, 2 months after the start of the outbreak, 1524 randomly selected inhabitants of Östersund municipality, including 1215 adults (born 1992 or earlier), were invited to complete a written questionnaire (outbreak questionnaire) sent to them by post. The questionnaire included items regarding demographics, cryptosporidiosis symptoms, health concerns in relation to the outbreak, and medical conditions, including pre-existing gastrointestinal disease. The questionnaire was returned by 1044 inhabitants (69.2%), of whom 53.4% were women. The response rate was the lowest among young adults (20–29 years old, 48.8%) and the highest among individuals >60 years of age (87.2–89.2%) (Widerström et al. 2014). Follow-up surveys were administered after 6 months, 2 years, and 5 years, by sending a questionnaire regarding possible sequelae to all individuals who responded to the outbreak questionnaire (Lilja et al. 2018; Rehn et al. 2015; Sjöström et al. 2022).

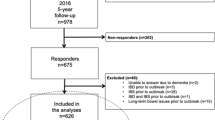

For the present study, in January 2021, a new follow-up questionnaire (10-year follow-up questionnaire, Supplement 1) was sent by post to the 727 adults who had replied to the outbreak questionnaire in 2011 (Fig. 1). The mailing included a pre-paid envelope to return the questionnaire, and a reminder was sent after 1 month. The respondents were asked to report whether they had experienced the following possible post-infectious symptoms during the last 3 months: loose stools, watery diarrhoea, bloody diarrhoea, change in bowel habits, abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, heartburn, loss of appetite, weight loss, headache, eye pain, fatigue, stiff joints, joint pain, swollen joints, and/or joint discomfort. They were also asked to report any other symptoms, and the extent to which they had concerns regarding their health. The questionnaire also included questions regarding the presence of the following conditions: IBS, IBD, gluten intolerance, lactose intolerance, other persisting abdominal issues, ulcers, diabetes, chronic lung diseases, heart failure, rheumatic disease, and cancer. Finally, we asked about the participants’ use of antacids, systemic corticosteroids, and immunomodulating drugs. The returned questionnaires were optically scanned and then transformed to a data file.

Case selection. A case was defined as a respondent who reported new episodes of diarrhoea (≥3 loose stools per day) and/or watery diarrhoea between November 1, 2010, and January 21, 2011, and who lived in Östersund municipality mid-January 2011. A non-case was defined as a respondent not fulfilling the case criteria. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease. IBS, irritable bowel syndrome

Exclusion

Respondents were excluded if they had a (self-reported) diagnosis of IBD, IBS, or other long-term bowel issues prior to the outbreak.

Case definition

A case was defined as a respondent who, on the outbreak questionnaire, reported new episodes of diarrhoea (≥3 loose stools daily) and/or watery diarrhoea with onset between November 1, 2010, and January 31, 2011 (World Health Organisation 2017). Respondents who did not fulfil these criteria were defined as non-cases.

Outcome measures

All reported symptoms, and their association with case status, were analysed separately. We also created composite outcomes, where there was considerable overlap in symptoms reported: abdominal symptoms included loose stools, watery and bloody diarrhoea, abdominal pain, constipation, changing bowel habits, and bloating; diarrhoea included loose stools, watery diarrhoea, and bloody diarrhoea; and joint symptoms included joint discomfort, stiff joints, joint pain, and swollen joints.

Medical conditions and use of medication were solely based on the participants’ answers on the questionnaires.

Symptoms over time were explored by merging the data from the 5- and 10-year follow-ups. We used the composite outcomes abdominal symptoms and joint symptoms, as well as fatigue and headache and divided the participants into three categories: consistent symptoms (the symptom was reported in both the 5- and 10-year follow-up); varying symptoms (the symptom was reported once, either in the 5- or 10-year follow-up); and no symptoms in either of the follow-ups.

Prolonged disease was determined based on the number of days with abdominal symptoms, as reported on the outbreak questionnaire. Prolonged disease was defined as ≥8 days of abdominal symptoms at the time of the outbreak.

In the outbreak questionnaire, participants rated their concerns about their own health in relation to the outbreak on a single scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no concerns at all, and 10 being very worried. The scale was converted to a dichotomous variable with ≥7/10 as the cut-off point for significant symptoms. This decision was based on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond and Snaith 1983) and similar scales on which significant symptoms are defined based on a score of at least 50–75% of the maximum score.

Statistical analyses

The study population was stratified according to case status, sex, and age at the time of the outbreak (18–40, 41–65, and ≥66 years). X2 tests and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to assess between-group differences in demographic variables and mean number of symptoms. We applied logistic regressions to examine associations between case status and symptoms reported on the follow-up questionnaire. The results were adjusted for age (category) and sex and presented as adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). X2 tests were used to evaluate possible association between prolonged disease during the outbreak and reported symptoms after 10 years, as well as to analyse the consistency of symptoms and their association with case status. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to examine an association between consistent symptoms and the mean number of days with symptoms during the outbreak. The dichotomous variable for health concerns was used to evaluate a possible association with the symptoms reported during follow-up, using logistic regression and with adjustment for age and sex. All statistical calculations were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Missing values were excluded from analysis. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

A total of 538 adults (74.0%) responded to the 10-year follow-up questionnaire. Response rates were the lowest (60.1%) among those who were 18–40 years old during the outbreak and the highest (81.1%) among those aged 41–65 years. Case status and sex did not differ between responders and non-responders (data not shown).

After exclusion of individuals who had IBD, IBS, or other long-term bowel issues prior to the outbreak, 493 individuals were included in the final analyses (Fig. 1), including 203 respondents defined as cases and 290 as non-cases. There were no sex differences between the groups. The median age at the time of the outbreak was 47.8 years (range 18–80 years) for cases and 52.7 years (18–89 years) for non-cases (p ≤ 0.001). Table 1 presents the detailed demographic information. Cases and non-cases did not differ in current smoking status or self-reported use of antacids, systemic corticosteroids, or immunomodulating agents. History of gastric ulcers was reported by no patients in the case group but 10 patients (3.6%) in the non-case group (p = 0.007). No other differences in comorbidities were found.

Reported symptoms after 10 years

Ten years after the outbreak, at least one symptom was reported by 59.6% of cases and 45.1% of non-cases. The mean number of symptoms among cases was 3.0 (range 0–15, median 2), while non-cases reported a mean of 1.7 symptoms (range 0–16, median 0) (p ≤ 0.001). The more frequently reported symptoms in the case group were bloating, headache, fatigue, and joint discomfort. Compared to the non-case group and corrected for age and sex, cases were significantly more likely to report abdominal symptoms (e.g. diarrhoea, changes in bowel habits, abdominal pain, nausea, bloating and heartburn); joint symptoms (e.g. joint pain, joint stiffness, and joint discomfort); and headaches, fatigue, and loss of appetite (Table 2). These results were not altered when the analyses were corrected for self-reported lactose intolerance and gluten intolerance (for abdominal symptoms) or rheumatic disease (for joint symptoms) at baseline (data not shown).

Among the cases, those who reported abdominal symptoms for ≥8 days on the outbreak questionnaire were more likely to report abdominal symptoms after 10 years (52.2%), compared to those who reported initial symptoms lasting up to 1 week (39.7%, p = 0.022). In 2021, more cases than non-cases cases reported a diagnosis of IBS (9.3% vs. 2.9%, p = 0.003) and lactose intolerance (11.2% vs. 6.1%, p = 0.048). Cases and non-cases did not differ in their reported use of medication.

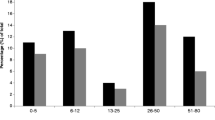

Symptoms over time

Among persons who responded to the 10-year follow-up questionnaire, 173 cases and 241 non-cases also replied to the 5-year follow-up questionnaire. Consistent symptoms were more commonly reported by cases compared to non-cases (Fig. 2). Among cases who reported consistent abdominal symptoms during both follow-ups, the mean duration of symptoms during the outbreak was 9.2 days (SD 8.1), compared to 6.6 days (SD 6.1) among cases reporting varying or no symptoms at follow-up (p = 0.003). Among those reporting varying symptoms, more participants tended to report symptoms during the 5-year follow-up compared to the 10-year follow-up, although this difference was not significant.

Consistency of symptoms over time, as reported by cases and non-cases. Percentages of participants reporting consistent, varying, or no symptoms, among cases and non-cases. Consistent: symptom reported after 5 and 10 years. Varying: symptom reported only after 5 or 10 years. None: symptom not reported. Abdominal symptoms: loose stools, watery or bloody diarrhoea, abdominal pain, constipation, changing bowel habits, and/or bloating. Joint symptoms: joint discomfort, joint pain, stiff joints, and/or swollen joints. X2 tests. Abdominal symptoms, joint symptoms, fatigue: p ≤ 0.001. Headache: p = 0.002

Health concerns

As expected, cases had more concerns regarding their health at the time of the outbreak, with 13.3% reporting significant health concerns, compared to 2.5% of non-cases (p ≤ 0.001). Among cases, those with significant concerns about their health reported more days with abdominal symptoms during the outbreak (mean 12.3 days, SD 7.9), compared to those without significant concerns (mean 7.0 days, SD 6.6) (p ≤ 0.001). Cases that had significant health concerns at the time of the outbreak tended to more commonly report symptoms after 10 years (63.3% vs. 50.5%). Correcting for health concerns at baseline in the logistic regression analyses only attenuated the results slightly. Compared to cases without significant health concerns during the outbreak, cases with significant health concerns did not report more significant concerns about their health during the 10-year follow-up.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, we evaluated the persistence of post-infectious symptoms 10 years after a large outbreak of C. hominis in Östersund, Sweden. Compared to non-cases, cases had a threefold greater risk of abdominal symptoms, and a twofold greater risk of joint symptoms, and more commonly reported having IBS and lactose intolerance diagnosed after the outbreak. Additionally, cases were more likely to report consistent symptoms over time. Among cases, those with prolonged disease during the outbreak were more likely to report symptoms 10 years later. Health concerns at baseline were not an independent risk factor for reporting sequelae during follow-up.

Results in context

To our knowledge, this is the first report of persisting post-infectious symptoms a decade after Cryptosporidium infection. The present results are in line with previous follow-ups of the same population (Lilja et al. 2018; Rehn et al. 2015; Sjöström et al. 2022). Long-term abdominal symptoms have also been reported in another Swedish study that included 271 individuals with laboratory-confirmed cryptosporidiosis. After up to 36 months, 15% experienced episodes of diarrhoea and 9% abdominal pain (Insulander et al. 2013). In a systematic review based on pooled estimates from eight studies, with a follow-up time of 2–36 months, the most common sequelae after cryptosporidiosis were diarrhoea (25%), abdominal pain (25%), nausea (24%), fatigue (25%), and headache (21%). In accordance with our present findings, that review showed that abdominal pain, loss of appetite, fatigue, vomiting, joint pain, headache, and eye pain were 2–3 times more likely to occur after a Cryptosporidium infection (Carter et al. 2020). A large Norwegian study following an outbreak with another parasite, Giardia lamblia, revealed that infection was associated with abdominal symptoms and chronic fatigue 10 years later (Litleskare et al. 2018). Even though the numbers of individuals reporting post-infectious symptoms are striking, it should be noted that we do not know to what extent these symptoms affect patients in their daily lives.

Acute gastroenteritis is associated with increased risk of IBS. A large meta-analysis showed that this relationship applies to infections with bacteria (e.g. Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., and Escherichia coli) but also for norovirus and the protozoan Giardia lamblia (Klem et al. 2017). The authors found a general PI-IBS prevalence of 11%, with the highest risk after protozoal infection (40%). Notably, these numbers were based on only one cohort, comprising patients with laboratory-confirmed G. lamblia infection (Hanevik et al. 2009; Hanevik et al. 2014; Wensaas et al. 2012). From the same cohort, a 10-year follow-up was published, reporting an IBS prevalence of 43% among cases and 14% among controls (OR 4.7, CI 3.6–6.2) and chronic fatigue in 26% vs. 11% (OR 3.0, CI 2.2–4.1) (Litleskare et al. 2018). Their findings strengthen the hypothesis that protozoan infection can result in long-term abdominal complaints.

A recent study demonstrated a 21% prevalence of PI-IBS at 6–9 months after Campylobacter infection, with an additional 9% suffering from new-onset abdominal pain and/or bowel disturbances that did not meet the Rome criteria (Berumen et al. 2021b). This suggests that the actual burden of chronic abdominal sequelae after gastrointestinal infections might be greater than what is captured by a PI-IBS diagnosis based on the Rome criteria.

It is likely that many of the individuals reporting abdominal symptoms in our study suffer from PI-IBS, but we cannot fully diagnose them based on our data. A validated questionnaire based on the Rome IV criteria is available for diagnosis, but it is extensive (Palsson et al. 2016). To improve the response rate, we did not include this questionnaire in our study, but the questions regarding abdominal symptoms were based on the criteria. Therefore, we can only conclude that some of our participants suffered from post-infectious IBS-like symptoms. Our results are strengthened by the finding that cases reported IBS diagnosis after the outbreak more often than non-cases (9.3% vs. 2.9%, p = 0.003). Cases also more commonly reported lactose intolerance, which is in line with a meta-analysis showing an OR of 3.5 (CI 1.6–7.6) for IBS patients compared to healthy controls (Varjú et al. 2019).

PI-IBS development is more common among younger individuals, women, and persons with severe disease (Berumen et al. 2021a; Klem et al. 2017). In a large meta-analysis based on 8 studies, diarrhoea lasting >7 days was associated with increased odds of PI-IBS (OR 2.62, 95% CI 1.48–4.61). Accordingly, in our present study, we found that individuals who reported at least 8 days of abdominal symptoms during their acute infection more commonly experienced abdominal symptoms during follow-up, compared to persons whose acute symptoms lasted up to one week (52.2% vs. 39.7%). Additionally, compared to cases who did not seem to have chronic symptoms, the cases who reported abdominal symptoms after both 5 and 10 years had experienced more symptomatic days during their acute infection (6.62 vs. 9.19 days).

Among those who reported varying symptoms during the follow-ups, more participants tended to report symptoms after 5 years than after 10 years; however, this difference was not significant. This trend might suggest that some individuals can recover from their ailments even after several years.

Anxiety and depression double the risk of IBS development and contribute to the maintenance of symptoms (Sibelli et al. 2016). To improve the response rate, our study did not include any validated questionnaire. Our results did not show that health concerns were an independent predictive factor for sequelae. We assume that the public largely considered cryptosporidiosis to be an annoying but harmless infection not to be worried about. Notably, one question about health concerns cannot replace an anxiety or depression diagnosis; therefore, it is not possible to draw further conclusions based on these results.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was its prospective design, following a cohort that was randomly selected shortly after the outbreak. The research team had broad knowledge in general practice, infectious diseases, and gastroenterology and was supported by an experienced statistician. We obtained high response rates for the outbreak questionnaire and for the follow-up questionnaires, without relevant differences between cases and non-cases. Östersund is the only city in a fairly isolated region; therefore, we expect that few other factors would have influenced the outcomes on a population level.

A limitation of this study was that cases were defined based on self-reported symptoms. During the outbreak, only 149 inhabitants had their Cryptosporidium infection confirmed by faecal microscopy. The strain identified in the stool samples was the same as in the drinking water, and no other pathogens were identified during microscopy (Widerström et al. 2014). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume the symptoms reported by our population were caused by C. hominis IbA10G2. However, relying on self-reported symptoms might have enabled misclassification of status for some individuals. Notably, we expect that this could be the case for individuals in both groups, and thus, we do not expect it to have affected the results. Moreover, to minimise the risk of misclassifying individuals with chronic diarrhoea as cases, and thereby overestimating associations between diarrhoea and case status, we excluded all individuals with long-term abdominal issues, including IBS and IBD, before the outbreak.

We did not have information about the participants’ current infection status at the time of follow-up. However, it is unlikely that respondents had a chronic Cryptosporidium infection causing long-term symptoms. At the time of the 2-year follow-up, participants were invited to submit stool samples, and all returned samples were negative for Cryptosporidium spp. (Lilja et al. 2018). Since the 10-year follow-up was conducted after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is possible that some reported symptoms were the result of a SARS-CoV-2 infection rather than long-term symptoms after a Cryptosporidium infection. However, this should have been equally possible for individuals in both groups and thus cannot explain the differences found.

With an increasing number of analyses, the risk of mass significance also increases. However, our results were consistently similar, which rather strengthens the outcomes.

Future research and clinical implications

Early recognition and appropriate management of post-infectious IBS may improve patient outcomes and reduce healthcare costs. Further research is needed to better understand the long-term effects of Cryptosporidium infection on gastrointestinal and joint symptoms, including the potential development of IBS. Additionally, the long-term effects of Cryptosporidium infection on children should be explored. It would also be beneficial to investigate the mechanisms underlying the persistence of symptoms and to develop effective treatment strategies for those affected.

Conclusions

Clinical cryptosporidiosis in adults was associated with a threefold risk of abdominal symptoms and a twofold risk of joint symptoms at 10 years after the initial infection. It is likely that many of the individuals reporting long-term abdominal symptoms had developed PI-IBS. An initial symptom duration of over 7 days during the acute infection was associated with an increased prevalence of long-term symptoms. Health concerns during the outbreak were not an independent risk factor. These results suggest that water treatment to prevent Cryptosporidium infections should be a priority for policy makers.

Data availability

The datasets used for the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aguilera-Lizarraga J, Hussein H, Boeckxstaens G (2022) Immune activation in irritable bowel syndrome: what is the evidence? Nat Rev Immunol 22:674–686. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00700-9

Axelrad JE, Cadwell KH, Colombel JF, Shah SC (2020) Systematic review: gastrointestinal infection and incident inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 51:1222–1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.15770

Berumen A, Edwinson AL, Grover M (2021a) Post-infection irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 50:445–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2021.02.007

Berumen A, Lennon R, Breen-Lyles M, Griffith J, Patel R, Boxrud D et al (2021b) Characteristics and risk factors of post-infection irritable bowel syndrome after Campylobacter enteritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 19:1855–63.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.033

Boks M, Lilja M, Widerström M, Karling P, Lindam A, Eriksson A et al (2022) Increased incidence of late-onset inflammatory bowel disease and microscopic colitis after a Cryptosporidium hominis outbreak. Scand J Gastroenterol 57:1443–1449. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2022.2094722

Bouzid M, Hunter PR, Chalmers RM, Tyler KM (2013) Cryptosporidium pathogenicity and virulence. Clin Microbiol Rev 26:115–134. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00076-12

Carter BL, Stiff RE, Elwin K, Hutchings HA, Mason BW, Davies AP et al (2019) Health sequelae of human cryptosporidiosis-a 12-month prospective follow-up study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 38:1709–1717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-019-03603-1

Carter BL, Chalmers RM, Davies AP (2020) Health sequelae of human cryptosporidiosis in industrialised countries: a systematic review. Parasit Vectors 13:443. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04308-7

Chalmers RM, Davies AP (2010) Minireview: clinical cryptosporidiosis. Exp Parasitol 124:138–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2009.02.003

Checkley W, White AC Jr, Jaganath D, Arrowood MJ, Chalmers RM, Chen XM et al (2015) A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for Cryptosporidium. Lancet Infect Dis 15:85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70772-8

Efstratiou A, Ongerth JE, Karanis P (2017) Waterborne transmission of protozoan parasites: review of worldwide outbreaks - an update 2011-2016. Water Res 114:14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2017.01.036

Feng Y, Ryan UM, Xiao L (2018) Genetic diversity and population structure of Cryptosporidium. Trends Parasitol 34:997–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2018.07.009

Hanevik K, Dizdar V, Langeland N, Hausken T (2009) Development of functional gastrointestinal disorders after Giardia lamblia infection. BMC Gastroenterol 9:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-9-27

Hanevik K, Wensaas KA, Rortveit G, Eide GE, Morch K, Langeland N (2014) Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue 6 years after Giardia infection: a controlled prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 59:1394–1400. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu629

Hunter PR, Hughes S, Woodhouse S, Raj N, Syed Q, Chalmers RM et al (2004) Health sequelae of human cryptosporidiosis in immunocompetent patients. Clin Infect Dis 39:504–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/422649

Iglói Z, Mughini-Gras L, Nic Lochlainn L, Barrasa A, Sane J, Mooij S et al (2018) Long-term sequelae of sporadic cryptosporidiosis: a follow-up study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 37:1377–1384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-018-3268-9

Insulander M, Silverlås C, Lebbad M, Karlsson L, Mattsson JG, Svenungsson B (2013) Molecular epidemiology and clinical manifestations of human cryptosporidiosis in Sweden. Epidemiol Infect 141:1009–1020. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268812001665

Klem F, Wadhwa A, Prokop LJ, Sundt WJ, Farrugia G, Camilleri M et al (2017) Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of irritable bowel syndrome after infectious enteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 152:1042–54.e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.039

Lilja M, Widerström M, Lindh J (2018) Persisting post-infection symptoms 2 years after a large waterborne outbreak of Cryptosporidium hominis in northern Sweden. BMC Res Notes 11:625. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3721-y

Litleskare S, Rortveit G, Eide GE, Hanevik K, Langeland N, Wensaas KA (2018) Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue 10 years after Giardia infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 16:1064–72.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.022

MacKenzie WR, Schell WL, Blair KA, Addiss DG, Peterson DE, Hoxie NJ et al (1995) Massive outbreak of waterborne Cryptosporidium infection in Milwaukee, Wisconsin: recurrence of illness and risk of secondary transmission. Clin Infect Dis 21:57–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/21.1.57

Palsson OS, Whitehead WE, van Tilburg MA, Chang L, Chey W, Crowell MD et al (2016) Rome IV diagnostic questionnaires and tables for investigators and clinicians. Gastroenterology 150:1481–1491. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.014

Pogreba-Brown K, Austhof E, Armstrong A, Schaefer K, Villa Zapata L, McClelland DJ et al (2020) Chronic gastrointestinal and joint-related sequelae associated with common foodborne illnesses: a scoping review. Foodborne Pathog Dis 17:67–86. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2019.2692

Rehn M, Wallensten A, Widerström M, Lilja M, Grunewald M, Stenmark S et al (2015) Post-infection symptoms following two large waterborne outbreaks of Cryptosporidium hominis in Northern Sweden, 2010-2011. BMC Public Health 15:529. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1871-6

Sibelli A, Chalder T, Everitt H, Workman P, Windgassen S, Moss-Morris R (2016) A systematic review with meta-analysis of the role of anxiety and depression in irritable bowel syndrome onset. Psychol Med 46:3065–3080. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001987

Sjöström M, Arvidsson M, Söderström L, Lilja M, Lindh J, Widerström M (2022) Outbreak of Cryptosporidium hominis in northern Sweden: persisting symptoms in a 5-year follow-up. Parasitol Res 121:2043–2039. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-022-07524-5

Varjú P, Gede N, Szakács Z, Hegyi P, Cazacu IM, Pécsi D et al (2019) Lactose intolerance but not lactose maldigestion is more frequent in patients with irritable bowel syndrome than in healthy controls: a meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil 31:e13527. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13527

Wensaas KA, Langeland N, Hanevik K, Morch K, Eide GE, Rortveit G (2012) Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue 3 years after acute giardiasis: historic cohort study. Gut 61:214–219. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300220

Widerström M, Schönning C, Lilja M, Lebbad M, Ljung T, Allestam G et al (2014) Large outbreak of Cryptosporidium hominis infection transmitted through the public water supply, Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis 20:581–589. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2004.121415

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

World Health Organisation (2017) Diarrhoeal disease. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease Accessed 10 Feb 2023

Funding

Open access funding provided by Umea University. This work was supported by the County Council Jämtland Härjedalen, under grant numbers JLL-939404, JLL-965542, JLL-967794, JLL-978075, and JLL-980156, and by VISARE NORR Fund, Northern County Councils Regional Federation, under grant number VISARENORR967799.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B.: study design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting the article; and final approval. M.L.: study design; data acquisition and interpretation; revising the article; and final approval. M.W.: study design; data acquisition and interpretation; revising the article; and final approval. P.K.: study design; data interpretation; revising the article; and final approval. A.L.: study design; data interpretation; revising the article; and final approval. M.S.: study design, data acquisition, and interpretation; revising the article; and final approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the regional research ethics review board in Umeå, Sweden (2010/392-31, 2015/495-31Ö), the regional research ethics review board in Stockholm (2011/220-31/4, 2011/1289-32), and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2020-05554).

Consent to participate

Respondents were informed in a written letter about the purpose of the study. Consent was given by completing the questionnaire.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Section Editor: Lihua Xiao

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boks, M., Lilja, M., Widerström, M. et al. Persisting symptoms after Cryptosporidium hominis outbreak: a 10-year follow-up from Östersund, Sweden. Parasitol Res 122, 1631–1639 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-023-07866-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-023-07866-8