Abstract

The study of cranial ontogeny is important for understanding the relationship between form and function in developmental, ecological, and evolutionary contexts. The transition from lactation to the diet of adult carnivores must be accompanied by pronounced modifications in skull morphology and feeding behavior. Our goal was to study relative growth and development in the skull ontogeny of the canid Lycalopex culpaeus, and interpret our findings in a functional context, thereby exploring the relationship between changes in shape and size with dietary habits and age stages. We performed quantitative analyses, including multivariate allometry and geometric morphometrics. Our results indicate that shape changes are related to functional improvements of the jaw mechanics related for food catching/processing. Estimates of full muscle size, mechanical advantage, and adult cranial shape are reached after sexual maturity, while adult mandible and skull size are reached after weaning, which is related to diet change (incorporation of meat and other food items). The ontogenetic pattern observed in L. culpaeus is similar to those observed in Canis familiaris and C. latrans. However, the magnitude of change seen in L. culpaeus is smaller than those seen in the felid Puma concolor and considerably smaller than those seen in the bone cracker hyaenid Crocuta crocuta. These patterns are associated with dietary habits and specializations in skull anatomy, as L. culpaeus, domestic dog and coyote are generalist species compared with hypercarnivores such as C. crocuta and P. concolor.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abdala F, Flores DA, Giannini NP (2001) Postweaning ontogeny in the skull in Didelphis albiventris. J Mamm 82:190–200

Anderson MJ (2001) A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Aust Ecol 26:32–46

Bekoff M (1974a) Social play in coyotes, wolves, and dogs. Bioscience 24:225–230

Bekoff M (1974b) Social play and play-soliciting by infant canids. Am Zool 14:323–340

Bekoff M, Jamieson R (1975) Physical development in coyotes (Canis latrans), with a comparison to other canids. J Mamm 56:685–692

Berta A (1987) Origin, diversification, and zoogeography of the south American Canidae. Fieldiana Zool 39:455–471

Biben M (1982) Object play and social treatment of prey in bush dogs and crab-eating foxes. Behaviour 79:201–211

Biben M (1983) Comparative ontogeny of social behaviour in three South American canids, the maned wolf, crab-eating fox and bush dog: implications for sociality. Ani Behav 31:814–826

Biknevicius AR, Leigh SR (1997) Patterns of growth of the mandibular corpus in spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) and cougars (Puma concolor). Zool J Linn Soc 120:139–161

Binder WJ, Van Valkenburgh B (2000) Development of bite strength and feeding behavior in juvenile spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta). J Zool 252:273–283

Bookstein FL (1991) Morphometric tools for landmark data. Geometry and biology. Cambridge University Press, USA

Bookstein FL (1997) Landmark methods for forms without landmarks: morphometrics of group differences in outline shape. Med Image Anal 1:225–243

Crespo JA, De Carlo JM (1963) Estudio ecológico de una población de zorros colorados Dusicyon culpaeus. Rev Mus Argent Cienc Nat 1:1–55

Drake AG (2011) Dispelling dog dogma: an investigation of heterochrony in dogs using 3D geometric morphometric analysis of skull shape. Evol Dev 13:204–213

Emerson SB, Bramble DM (1993) Scaling, allometry and skull design. In: Hanken J, Hall BK (eds) The skull. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 384–416

Evans HE (1993) Miller’s anatomy of the dog, 3rd edn. W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia

Ewer R (1973) The carnivores. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Finarelli JA, Goswami A (2009) The evolution of orbit orientation and encephalization in the carnivora (Mammalia). J Anat 214:671–678

Flores DA, Giannini NP, Abdala F (2003) Cranial ontogeny on Lutreolina crassicaudata (Didelphidae): a comparison with Didelphis albiventris. Acta Theriol 48:1–9

Flores DA, Giannini NP, Abdala F (2006) Comparative postnatal ontogeny of the skull in an Australidelphian Metatherian, Dasyurus albopunctatus (Marsupialia: Dasyuromorpha: Dasyuridae). J Morphol 267:426–440

Flores DA, Giannini NP, Abdala F (2010) Cranial ontogeny of Caluromys philander (Didelphidae: Caluromyinae): a qualitative and quantitative approach. J Mamm 91:539–550

Fox MW (1964) The ontogeny of behaviour and neurologic responses in the dog. Ani Behav 12:301–310

Fox MW (1969) Ontogeny of prey-killing behavior in Canidae. Behaviour 35:259–272

Gay SW, Best TL (1996) Age-related variation in skulls of the puma (Puma concolor). J Mamm 77:191–198

Giannini NP, Abdala F, Flores DA (2004) Comparative postnatal ontogeny of the skull in Dromiciops gliroides (Marsupialia: Microbiotheriidae). Am Mus Novit 3460:1–17

Giannini NP, Segura V, Giannini MI, Flores D (2010) A quantitative approach to the cranial ontogeny of the puma. Mamm Biol 75:547–554

Goodall C (1991) Procrustes methods in the statistical analysis of shape. J R Stat Soc 53:285–339

Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD (2001) PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electronica 4:1–9. http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/past.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2011

Holekamp KE, Kolowski JM (2009) Family Hyaenidae (Hyenas). In: Wilson DE, Mittermeier RA (eds) Handbook of the mammals of the world 1 carnivores. Lynx Editions, Barcelona, pp 234–260

Jiménez JE, Novaro AJ (2004) Pseudalopex culpaeus (Molina, 1782). In: Sillero-Zubiri C, Hoffmann M, Macdonald DW (eds) Canids: foxes, wolves, jackals and dogs. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group, Gland, pp 44–49

Johnson WE, Franklin WL (1994) Role of body size in the diets of sympatric gray and culpeo foxes. J Mamm 75:163–174

Jolicoeur P (1963a) The multivariate generalization of the allometry equation. Biometrics 19:497–499

Jolicoeur P (1963b) The degree of generality of robustness in Martes americana. Growth 27:1–27

Kraglievich L (1930) Craneometría y clasificación de los cánidos sudamericanos, especialmente los argentinos actuales y fósiles. Physis 10:35–73

Kremenak CR (1969) Dental eruption chronology in dogs: deciduous tooth gingival emergence. J Dent Res 48:1177–1184

Kremenak CR, Russell LS, Christensen RD (1969) Tooth-eruption ages in suckling dogs as affected by local heating. J Dent Res 48:427–430

La Croix S, Holekamp KE, Shivik JA, Lundrigan BL, Zelditch ML (2011) Ontogenetic relationships between cranium and mandible in coyotes and hyenas. J Morphol 272:662–674

Manly BFJ (1997) Randomization, bootstrap, and Monte Carlo methods in biology. Chapman & Hall, New York

Moore WJ (1981) The mammalian skull. Cambridge University Press, UK

Noble VE, Kowalski EM, Ravosa MJ (2000) Orbit orientation and the function of the mammalian postorbital bar. J Zool 250:405–418

Novaro AJ (1997) Pseudalopex culpaeus. Mamm Species 558:1–8

Prevosti FJ, Lamas L (2006) Variation of cranial and dental measurements and dental correlations in the pampean fox Dusicyon gymnocercus. J Zool 270:636–649

Radinsky LB (1981) Evolution of skull shape in carnivores. I. Representative modern carnivores. Biol J Linn Soc 15:369–388

Ravosa MJ, Noble V, Hylander W, Johnson K, Kowalski E (2000) Masticatory stress, orbital orientation and the evolution of the primate postorbital bar. J Hum Evol 38:667–693

Rohlf FJ (1999) Shape statistics: procrustes method for the optimal superimposition of landmarks. Syst Zool 39:40–59

Rohlf FJ (2003a) TpsRegr version 1.28. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook. http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/. Accessed 2 March 2011

Rohlf FJ (2003b) TpsRelw version 1.35. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook. http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/. Accessed 2 March 2011

Rohlf FJ (2008a) TpsUtil version 1.40. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook. http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/. Accessed 2 March 2011

Rohlf FJ (2008b) TpsDig version 2.12. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook. http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/. Accessed 2 March 2011

Scott JP (1967) The evolution of social behavior in dogs and wolves. Am Zool 7:373–381

Segura V, Flores D (2009) Aproximación cualitativa y aspectos funcionales en la ontogenia craneana de Puma concolor (felidae). Mastozool Neotrop 16:169–182

Sheets HD (2002) IMP-integrated morphometrics package. Department of Physics, Casius College, Buffalo

Slater GJ, Dumont E, Van Valkenburgh B (2009) Implications of predatory specialization for cranial form and function in canids. J Zool 278:181–188

Tanner JB, Zelditch ML, Lundrigan BL, Holekamp KE (2010) Ontogenetic change in skull morphology and mechanical advantage in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta). J Morphol 271:353–365

R Development Core Team (2004) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. http://www.rproject.org. Accessed 26 Feb 2011

Travaini A, Juste J, Novaro A, Capurro A (2000) Sexual dimorphism and sex identification in the South American culpeo fox, Pseudalopex culpaeus (Carnivora: Canidae). Wildlife Res 27:669–674

Tseng ZJ (2009) Cranial function in a late Miocene Dinocrocuta gigantea (Mammalia: Carnivora) revealed by comparative finite element analysis. Biol J Linn Soc 96:51–67

Tseng ZJ, Binder WJ (2010) Mandibular biomechanics of Crocuta crocuta, Canis lupus, and the late Miocene Dinocrocuta gigantea (Carnivora, Mammalia). Zool J Linn Soc 158:683–696

Tseng ZJ, Wang X (2010) Cranial functional morphology of fossil dogs and adaptation for durophagy in Borophagus and Epicyon (Carnivora, Mammalia). J Morphol 271:1386–1398

Tukey JW (1956) Bias and confidence in not quite large samples. Ann Math Stat 23:614

Van Valkenburgh B (1988) Trophic diversity in past and present guilds of large predatory mammals. Paleobiology 14:155–173

Van Valkenburgh B (1989) Carnivore dental adaptations and diet: a study of trophic diversity within guilds. In: Gittleman JL (ed) Carnivore behavior, ecology, and evolution. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, pp 410–436

Van Valkenburgh B (2007) Déjà vu: the evolution of feeding morphologies in the carnivora. Integr Comp Biol 47:147–163

Van Valkenburgh B, Koepfli KP (1993) Cranial and dental adaptations to predation in canids. Symp Zool Soc Lond 65:15–37

Wayne RK (1986) Cranial morphology of domestic and wild canids: the influence of development on morphological change. Evolution 40:243–261

Zapata SC, Funes M, Novaro A (1997) Estimación de la edad en el zorro colorado patagónico (Pseudalopex culpaeus). Mastozool Neotrop 4:145–150

Zar JH (1984) Biostatistical analysis. Prentice-Hall Inc, Englewood Cliff

Zelditch ML, Swiderski D, Sheets H, Fink W (2004) Geometric morphometrics for biologists: a primer. Elsevier Academic Press, London

Acknowledgments

We thank David Flores for the permission to study the material under his care; to Pablo Teta for his drawings of L. culpaeus skulls; to Erika Hingst-Zaher, Amelia Chemisquy, and David Flores for their critical revision of the preliminary version of this manuscript and to Cecilia Morgan for her revision of English grammar. We also thank to three anonymous reviewers who provided many helpful suggestions to this study. This research was partially supported by CONICET (PIP 01054) and ANPCyT (PICT 2008-1798).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by T. Bartolomaeus.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

435_2012_145_MOESM2_ESM.tif

Fig. S1. Boxplots of skull centroid size vs. age classes of Lycalopex culpaeus, for dorsal (A), lateral (B), ventral (C), and mandible (D) view. The boxplots include median, upper, and lower quartiles (75 and 25%, respectively), minimum and maximum. Supplementary material 2 (TIFF 382 kb)

435_2012_145_MOESM3_ESM.tif

Fig. S2. Boxplots of skull procrustes distance of each specimen of all age classes Lycalopex culpaeus to the mean of J1 class, for dorsal (A), lateral (B), ventral (C), and mandible (D) view. The boxplots include median, upper, and lower quartiles (75 and 25%, respectively), minimum and maximum. Supplementary material 3 (TIFF 358 kb)

435_2012_145_MOESM4_ESM.tif

Fig. S3. Boxplots of mechanical advantage of masseter and temporal muscles (in-levers of masseteric and temporal muscles/out-lever at canine and carnassial) vs. age classes of Lycalopex culpaeus. Zygomatic breadth (A), mechanical advantage of masseter muscle measure at the canine (B), mechanical advantage of masseter muscle measure at the carnassial (C), mechanical advantage of temporal muscle measure at the canine (D), and mechanical advantage of temporal muscle measure at the carnassial (E). The boxplots include median, upper, and lower quartiles (75 and 25%, respectively), minimum and maximum. Supplementary material 4 (TIFF 429 kb)

Appendices

Appendix 1

Specimens of Lycalopex culpaeus of Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales Bernardino Rivadavia (MACN) used in this study

15022; 15024; 15025; 15028; 15033; 15037; 15040; 15044; 15045; 15049; 15050;15055; 15062; 15063; 15064; 15073; 15078; 15081; 15082; 15083; 15089; 15093; 15096; 15101; 15106; 15112; 15119; 15121; 15122; 15123; 15124; 15127; 15129; 15130; 15131; 15132; 15133; 15138; 15140; 15149; 15151; 15154; 15158; 15163; 15168; 15172; 15173; 15177; 15180; 15181; 15182; 15190; 15194; 15196; 15197; 15199; 15200; 15201; 15202; 15203; 15208; 15212; 15220; 15223; 15224; 15226; 15227; 15228; 15229; 15232; 15233; 15240; 15243; 15246; 15248; 15258; 15259; 15260; 15261; 15266; 15267; 15268; 23072; 23076; 23077; 23093; 23095; 23098; 23099; 23100; 23101; 23102; 23103; 23104; 23108; 23119; 23123; 23125; 23143; 23148; 23152.

Appendix 2

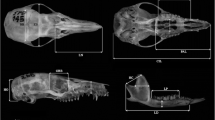

Definition of the landmarks and semi-landmarks used in the geometric morphometric analyses (see Fig. 1)

Dorsal landmarks: 1, tip of premaxilla in the sutura interincisiva; 2, anterior portion of the nasals in the sutura internasalis; 3, midline of sutura frontonasalis; 4, intersection between sutura coronalis, sutura sagittalis, and sutura interfrontalis; 5, tip of occipital plate; 6–16, semi-landmarks; 17, tip of the supraorbital process; 18–24, semi-landmarks; 25, lacrimal foramen; 26–31, semi-landmarks; 32, tip of the infraorbital process; 33–37, semi-landmarks; 38, apex of canine root; 39, nasal process; 40, anterior contact of sutura nasomaxillaris; 41, posterior contact of sutura nasomaxillaris; 42, apex of sutura frontomaxillaris.

Ventral landmarks: 1, anterior tip of premaxilla; 2, midline in Sutura incisivomaxillaris; 3, midline in Sutura palatomaxillaris; 4, posterior point of palatine torus; 5, anterior point of intercondyloid incisure; 6, internal apex of occipital condyle; 7, apex of jugular process. 8, tip of mastoid process; 9, internal apex of tympanic bulla; 10, anterior apex of tympanic bulla; 11–14, semi-landmarks; 15, tip of postglenoid process; 16, internal edge of masseteric fossa; 17, caudal apex of border of palatine; 18, external edge of masseteric fossa; 19, anterior edge of masseteric fossa; 20–30, semi-landmarks.

Lateral landmarks: 1, tip of premaxilla; 2–3, semi-landmarks; 4, apex of sutura frontomaxillaris; 5–8, semi-landmarks; 9, posterior point between sagittal and nuchal crests; 10, apex of occipital condyle; 11, tip of paracondylar process; 12, point between nuchal crest and mastoid process; 13, apex of tympanic bulla; 14–17, semi-landmarks; 18, tip of infraorbital process; 19–20, semi-landmarks; 21, lacrimal foramen; 22–23, semi-landmarks; 24, tip of the supraorbital process; 25, tip of Postglenoid process; 26, posterior point of pterygoid; 27–29, semi-landmarks; 30, posterior tip of dentary row; 31, notch of carnassial; and 32–33, semi-landmarks.

Mandibular landmarks: 1, anterior tip of body of mandible; 2–9, semi-landmarks; 10, posterior tip of coronoid process; 11, mandibular notch; 12, anterior point of masseteric fossa; 13, external point of condyloid process; 14, separation between condyloid and angular process; 15, tip of angular process; 16–22, semi-landmarks.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Segura, V., Prevosti, F. A quantitative approach to the cranial ontogeny of Lycalopex culpaeus (Carnivora: Canidae). Zoomorphology 131, 79–92 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-012-0145-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-012-0145-4