Abstract

Purpose

EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy in EGFR-mutated lung cancer is limited by acquired resistance. In half of the patients treated with first/second-generation (1st/2nd gen) TKI, resistance is associated with EGFR p.T790M mutation. Sequential treatment with osimertinib is highly active in such patients. Currently, there is no approved targeted second-line option for patients receiving first-line osimertinib, which thus may not be the best choice for all patients. The present study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of a sequential TKI treatment with 1st/2nd gen TKI, followed by osimertinib in a real-world setting.

Methods

Patients with EGFR-mutated lung cancer treated at two major comprehensive cancer centers were retrospectively analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method and log rank test.

Results

A cohort of 150 patients, of which 133 received first-line treatment with a first/second gen EGFR TKI, and 17 received first-line osimertinib, was included. Median age was 63.9 years, 55% had ECOG performance score of ≥ 1. First-line osimertinib was associated with prolonged progression-free survival (P = 0.038). Since the approval of osimertinib (February 2016), 91 patients were under treatment with a 1st/2nd gen TKI. Median overall survival (OS) of this cohort was 39.3 months. At data cutoff, 87% had progressed. Of those, 92% underwent new biomarker analyses, revealing EGFR p.T790M in 51%. Overall, 91% of progressing patients received second-line therapy, which was osimertinib in 46%. Median OS with sequenced osimertinib was 50 months. Median OS of patients with p.T790M-negative progression was 23.4 months.

Conclusion

Real-world survival outcomes of patients with EGFR-mutated lung cancer may be superior with a sequenced TKI strategy. Predictors of p.T790M-associated resistance are needed to personalize first-line treatment decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Approximately, 12–15% of non-squamous non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) are molecularly characterized by an activating mutation in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2014; Rosell et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2016). Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) are the optimal first-line treatment of patients with stage IV NSCLC harboring TKI-sensitive EGFR mutations (Maemondo et al. 2010; Ramalingam et al. 2020; Rosell et al. 2012; Sequist et al. 2013; Wu et al. 2014, 2017). FDA- and EMA-approved first generation (1st gen) TKI erlotinib and gefitinib bind solely and reversibly to EGFR, whereas second generation (2nd gen) TKI afatinib and dacomitinib bind irreversibly to EGFR, HER2 and HER4, which highlights relevant molecular and clinical differences between 1st and 2nd gen TKIs (Li et al. 2008; Robichaux et al. 2021). The clinical benefit of TKI treatment is generally limited by the inevitable development of acquired resistance, which is associated with the EGFR p.T790M gatekeeper mutation in approximately 50–60% of patients treated with 1st or 2nd gen EGFR TKI (Yu et al. 2013). 3rd gen TKI osimertinib was specially designed to target EGFR p.T790M resistance mutation (Cross et al. 2014). In patients who developed p.T790M resistance mutation, a sequential treatment with osimertinib is highly active (Mok et al. 2017; Papadimitrakopoulou et al. 2020). Recently, first-line osimertinib was approved based on superior progression-free survival (PFS) in comparison to 1st gen EGFR TKI (Soria et al. 2018). A survival benefit for first-line osimertinib was also reported, but 30% of patients received no second-line treatment and data are still immature (Ramalingam et al. 2020). There is no approved sequential targeted therapy for patients progressing on first-line osimertinib and chemotherapy/immunotherapy is of limited activity (Hastings et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2017; Lisberg et al. 2018; Mok et al. 2017; Papadimitrakopoulou et al. 2020). Hence, first-line treatment with a 1st/2nd gen EGFR TKI followed by osimertinib at confirmation of p.T790M-mediated resistance may be a superior strategy in some patients. Here, we explored the outcome of a sequential treatment approach in a real-world patient population treated at two German comprehensive cancer centers.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

Patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC treated with 1st, 2nd or 3rd gen TKIs at the West German Cancer Center (WTZ), University Hospital Essen and the University Tumor Center (UTC), University Hospital Frankfurt, between January 2008 and January 2021 were included. All treatment and follow-up data were documented in the electronic health records (EHR). Clinico-pathological parameters, treatment trajectories and outcomes were also retrieved from the EHR. The data cutoff for follow-up was March 17, 2021. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Medical Faculty of the University Duisburg-Essen and the University of Frankfurt (19-8585-BO).

Clinical assessments

Routine staging procedures included a whole-body (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET-CT) or computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest and abdomen, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Tumor staging was based on the 8th Edition of the UICC/WHO staging system. Under TKI treatment, radiological assessments were performed every 10–12 weeks according to the institutional guidelines of the WTZ and UTC. The response rate was retrospectively evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors 1.1 (RECIST 1.1) (Eisenhauer et al. 2009; Therasse et al. 2000). Response assessment was feasible if at least baseline and one follow-up imaging dataset were available. Overall survival was defined as time from first administration of palliative TKI treatment to death from any cause. Patients were censored at the time of last follow-up, if time of death was unknown. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as time from the start of TKI therapy to date of radiologic progression or death.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (V26, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and MS Excel 2010 (VS 14.0, Microsoft, Richmond, WA, USA). Survival analyses were performed by the Kaplan–Meier method and log rank test. Comparison of p.T790M acquisition was analyzed through Chi-square test for categorical data.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

A total of 150 patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC treated in first line with 1st, 2nd or 3rd gen TKI were included in this analysis. Baseline clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 63.9 years (range 35.7–87.4) with 32.0% (N = 48) of patients older than 70 years at the start of the first TKI. Notably, 82 patients (54.7%) had an ECOG performance status of 1 or higher. More patients were female (65.3%, N = 98), never/light smokers with a smoking history of less than 10 pack years (63.3%, N = 95). EGFR exon 19 in-frame deletions were the most prevalent mutations (58.7%, N = 88). A total of 112 patients (74.7%) were initially diagnosed with systemic disease (stages IV A/B), whereas 38 patients initially had stage I–III disease (25.3%).

First-line treatments

All patients initially diagnosed with stage I–III disease were initially treated with curative intent, which is also detailed in Table 1. 1st gen TKI (erlotinib or gefitinib) was administered as first-line TKI in 59 patients (39.3%), 74 patients (49.3%) received first-line treatment with afatinib, and 17 patients (11.3%) received osimertinib as their first-line TKI.

Outcomes of first-line treatments

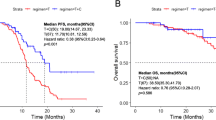

Progression-free survival under first-line TKI treatment was superior in patients receiving osimertinib as compared to 1st/2nd gen TKIs (median not reached vs 12.2 months, P = 0.038) (Fig. 1). In total, 137 patients (91.3%) were evaluable for response according to RECIST 1.1. Response rates (RR) and disease control rates (DCR) for first-line osimertinib and 1st/2nd gen TKIs were 73.3% vs. 64.8% and 93.3% vs. 92.6%, respectively (Fig. 2).

Osimertinib was EMA approved for treatment of EGFR p.T790M-positive metastatic NSCLC in February 2016, providing immediate access and reimbursement in Germany. Since February 2016, 91 of the 150 patients were under first-line treatment with a 1st/2nd gen TKI and had therefore the option of second-line osimertinib in case of EGFR p.T790M-positive progression. EMA approval for osimertinib was extended to the first-line setting in June 2018, and 17 of 150 patients received osimertinib as their first TKI. Combined median overall survival (OS) of these two cohorts (N = 108) was 39.3 months (95% CI 31.1–47.5 months). There was no survival difference between the cohorts (median not reached vs. 39.3 months, 95% CI 30.8–47.7, P = 0.879) (Fig. 3).

Biomarker analyses at progression and further line treatments

As of March 1, 2021, 79 of 91 of patients had progressed. Of those, 73 patients (92%) underwent a new biomarker analysis (Fig. 4), which identified the EGFR p.T790M resistance mutation in 37 patients (51%).

In total, 72 of 79 patients (91%) received second-line therapy, including 36 patients with EGFR p.T790M-associated progression. All of those p.T790M-positive patients received second-line osimertinib. Those patients had a superior overall survival as compared to patients receiving second-line chemotherapy for progression with EGFR p.T790M-negative rebiopsy (median 50.0 months, 95% CI 32.2–67.8, vs. 23.4 months, 95% CI 18.0–28.8, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5).

Detection of p.T790M resistance mutation in new biomarker analysis after progression on first-line TKI was associated with age < 65 years (P = 0.026), common EGFR mutation del exon 19/L858R (P = 0.022) and 1st gen TKI (P = 0.009) (Table 2).

Treatment after failure of osimertinib

The preferred treatment option after failure of first-line osimertinib was platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with checkpoint inhibitor atezolizumab and anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab (Table 3). Patients positive for p.T790M and progressing on second-line osimertinib mainly received platinum in combination with pemetrexed. Prognosis after progression on osimertinib was limited with a median PFS for first subsequent therapy after failure of first-line osimertinib of 4.5 months (95% CI 2.0–7.1) and a median PFS of 3.4 months (95% CI 0.9–5.9) for first subsequent therapy after failure of osimertinib in p.T790M-positive patients in the second-line setting. Median OS was 6.9 months (95% CI 4.6–9.2) from the start of first subsequent therapy after progression on first-line osimertinib and 5.6 months (95% CI 3.1–8.2) from the start of first subsequent therapy after failure of second-line osimertinib.

Discussion

Osimertinib is currently the most potent TKI for first-line treatment of patient with metastatic NSCLC harboring common (delEx19, L858R) EGFR mutations in terms of progression-free survival (Soria et al. 2018). Currently known mechanisms of acquired resistance to first-line osimertinib are diverse and provide no direct path to a sequenced targeted therapy. Hence, patients progressing under osimertinib are offered chemotherapies, which have limited efficacy in TKI-pretreated patient populations (Mok et al. 2017; Papadimitrakopoulou et al. 2020). These findings are in line with the poor patients’ prognosis in our cohort after failure of osimertinib in the first-line, and in the second-line setting with a median overall survival of 6.9 months (95% CI 4.6–9.2) and 5.6 months (95% CI 3.1–8.2), respectively. Treatment after failure of first-line osimertinib was mainly atezolizumab/bevacizumab/carboplatin/paclitaxel, and platinum/pemetrexed after p.T790M-positive progression on second-line osimertinib. The limited efficacy of chemotherapy-based treatment after failure of osimertinib was underlined by a median PFS of 4.5 months (95% CI 2.0–7.1) and 3.4 months (0.9–5.9), respectively.

The approval of osimertinib is based on the pivotal FLAURA study, which enrolled patients with ECOG 0–1. For patients randomized to the control arm, access to 3rd gen TKIs at progression was high, making OS data relevant. However, the most recent full publication of OS data was still only 58% mature, and a relatively high proportion of patients (30% in both arms) received no post-progression therapy (Ramalingam et al. 2020). Recent studies combining erlotinib with antiangiogenic biologicals leading to approvals have reported PFS rates comparable to osimertinib in FLAURA, while still enabling second-line osimertinib to approximately 50% of patients developing EGFR p.T790M-associated resistance (Nakagawa et al. 2019; Saito et al. 2019). The same is true for studies combining first-line gefitinib with chemotherapy, which led to an improved overall survival compared to gefitinib alone (Noronha et al. 2020). This option is not approved in the EMA legislature. To date, there is no direct comparison of these approaches to first-line osimertinib.

Based on its favorable toxicity profile as compared to TKI targeting wild-type receptors, osimertinib is clearly the first-line TKI of choice for patients less likely to undergo further line therapy, such as frail or comorbid populations. The presence of asymptomatic brain metastases is also used in support of first-line osimertinib. However, treatment decisions are less clear in less comorbid patients with good performance status. Until final OS data and data from studies directly comparing osimertinib with approved 2nd gen TKI (afatinib, dacomitinib), erlotinib/antiangiogenic and gefitinib/chemotherapy combinations become available, selection of the first-line EGFR TKI should be supported by real-world evidence matching the cancer care setting and patient population at the treating center for shared decision making.

Against this background, we have conducted a retrospective analysis of outcomes with TKI therapy in a contemporary cohort of patients treated at two German comprehensive cancer centers. To explore the impact of osimertinib use as second-line TKI in patients with EGFR p.T790M-associated resistance to 1st/2nd gen TKI, we particularly focused on those patients that were under TKI treatment (or initiated TKI treatment) after EMA approval and reimbursement of osimertinib. Overall survival of this population, which received sequenced osimertinib in approximately 50% of patients, was compared and found to be favorable to the overall survival observed in the control arm of FLAURA, which was largely treated following the same algorithm (Ramalingam et al. 2020). Moreover, it also compared favorably to the reported OS of the osimertinib arm of FLAURA. As expected, this good outcome was strongly impacted by those patients acquiring EGFR p.T790M-associated resistance and subsequently receiving osimertinib. These findings are in line with other recently published comprehensive real-world data analysis (Magios et al. 2021). Certainly, selection bias cannot be excluded as patients were treated at two academic comprehensive cancer centers serving densely populated metropolitan areas. On the other hand, our cohort included a high fraction of patients with ECOG PS 2 or 3, who were excluded from FLAURA.

Potentially, careful patient management demonstrated by a rate of 92% of second biomarker analyses in case of progression and a rate of 91% for post-progression therapy might have played a major role in these positive survival outcomes. Nevertheless, it has to be strongly emphasized that patients experiencing EGFR p.T790M-negative resistance unfortunately show a numerically inferior survival as compared to the osimertinib arm of FLAURA (Ramalingam et al. 2020).

Detection of p.T790M in second biomarker analysis after progression on first-line TKI was significantly associated with younger age (< 65 years). Given the relatively small sample size (N = 73), these findings should be interpreted with caution. A trend toward a relation between younger age and p.T790M-positive progression was reported in a published retrospective analysis, but did not reach statistical significance (Wu SG et al. 2020). Moreover, detection of p.T790M was positively associated with 1st gen TKI as first-line TKI. Wu SG et al. reported a statistically significant difference in p.T790 detection between 1st gen TKI gefitinib and 2nd gen TKI afatinib, but not between 1st gen erlotinib and 2nd gen afatinib. These findings clearly need validation in larger cohorts and in a prospective fashion. Furthermore, our data show a strong association between common EGFR mutation (del 19, L858R) and development of p.T790M compared to rare EGFR mutations, which is in line with the literature (Yang et al. 2020).

Conclusion

With our data and the published evidence combined, it appears highly attractive to personalize the first-line TKI selection based on an upfront prediction of the likelihood of developing EGFR p.T790M-mediated resistance. Those patients could benefit by a sequence of a 1st/2nd gen TKI, potentially combined with an anti-VEGF treatment strategy like bevacizumab or ramucirumab, followed by osimertinib. Patients developing other mechanisms of resistance will be better served with first-line osimertinib. Therefore, predictors of p.T790M-associated resistance are needed to optimize first-line treatment decisions. Until such tools have emerged and more definitive data from comparative clinical trials become available, shared decision making on the selection of the first-line EGFR TKI might be based on a comprehensive discussion and risk–benefit evaluation between patients and the treating thoracic oncologist.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cancer Genome Atlas Research N (2014) Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 511:543–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13385

Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S, Eberlein C, Nebhan CA, Spitzler PJ et al (2014) AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov 4:1046–1061. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0337

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026

Hastings K, Yu HA, Wei W, Sanchez-Vega F, DeVeaux M, Choi J et al (2019) EGFR mutation subtypes and response to immune checkpoint blockade treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 30:1311–1320. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz141

Lee CK, Man J, Lord S, Links M, Gebski V, Mok T, Yang JC (2017) Checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic egfr-mutated non-small cell lung cancer-a meta-analysis. J Thorac Oncol 12:403–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2016.10.007

Li D, Ambrogio L, Shimamura T, Kubo S, Takahashi M, Chirieac LR et al (2008) BIBW2992, an irreversible EGFR/HER2 inhibitor highly effective in preclinical lung cancer models. Oncogene 27:4702–4711. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2008.109

Lisberg A, Cummings A, Goldman JW, Bornazyan K, Reese N, Wang T et al (2018) A phase II study of pembrolizumab in EGFR-mutant, PD-L1+, tyrosine kinase inhibitor naive patients with advanced NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 13:1138–1145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.03.035

Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H et al (2010) Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med 362:2380–2388. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0909530

Magios N, Bozorgmehr F, Volckmar AL, Kazdal D, Kirchner M, Herth FJ et al (2021) Real-world implementation of sequential targeted therapies for EGFR-mutated lung cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol 13:1758835921996509. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758835921996509

Mok TS, Wu YL, Ahn MJ, Garassino MC, Kim HR, Ramalingam SS et al (2017) Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 376:629–640. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1612674

Nakagawa K, Garon EB, Seto T, Nishio M, Ponce Aix S, Paz-Ares L et al (2019) Ramucirumab plus erlotinib in patients with untreated, EGFR-mutated, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (RELAY): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 20:1655–1669. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30634-5

Noronha V, Patil VM, Joshi A, Menon N, Chougule A, Mahajan A et al (2020) Gefitinib versus gefitinib plus pemetrexed and carboplatin chemotherapy in EGFR-mutated lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 38:124–136. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.01154

Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Mok TS, Han JY, Ahn MJ, Delmonte A, Ramalingam SS et al (2020) Osimertinib versus platinum-pemetrexed for patients with EGFR T790M advanced NSCLC and progression on a prior EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor: AURA3 overall survival analysis. Ann Oncol 31:1536–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.2100

Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D, Cho BC, Gray JE, Ohe Y et al (2020) Overall survival with osimertinib in untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med 382:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1913662

Robichaux JP, Le X, Vijayan RSK, Hicks JK, Heeke S, Elamin YY et al (2021) Structure-based classification predicts drug response in EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Nature 597:732–737. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03898-1

Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C, Porta R, Cardenal F, Camps C et al (2009) Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. N Engl J Med 361:958–967. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0904554

Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Feli E et al (2012) Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 13:239–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X

Saito H, Fukuhara T, Furuya N, Watanabe K, Sugawara S, Iwasawa S et al (2019) Erlotinib plus bevacizumab versus erlotinib alone in patients with EGFR-positive advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (NEJ026): interim analysis of an open-label, randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 20:625–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30035-X

Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, O’Byrne K, Hirsh V, Mok T et al (2013) Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol 31:3327–3334. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806

Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, Reungwetwattana T, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH et al (2018) Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 378:113–125. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1713137

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L et al (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:205–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/92.3.205

Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP, Feng J, Lu S, Huang Y et al (2014) Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 15:213–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70604-1

Wu YL, Cheng Y, Zhou X, Lee KH, Nakagawa K, Niho S et al (2017) Dacomitinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ARCHER 1050): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 18:1454–1466. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30608-3

Wu SG, Chiang CL, Liu CY, Wang CC, Su PL, Hsia TC et al (2020) An observational study of acquired EGFR T790M-dependent resistance to EGFR-TKI treatment in lung adenocarcinoma patients in Taiwan. Front Oncol 10:1481. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01481

Yang S, Mao S, Li X, Zhao C, Liu Q, Yu X et al (2020) Uncommon EGFR mutations associate with lower incidence of T790M mutation after EGFR-TKI treatment in patients with advanced NSCLC. Lung Cancer 139:133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.11.018

Yu HA, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, Sima CS, Zakowski MF, Pao W et al (2013) Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res 19:2240–7. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2246

Zhang YL, Yuan JQ, Wang KF, Fu XH, Han XR, Threapleton D et al (2016) The prevalence of EGFR mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 7:78985–78993. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12587

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support was received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP, MSe, and MSc were responsible for the conception and design of this study. OK, JS, MW, WE, MM, KWS, TH, HUS, KD, CA, MSt, KL, GZ, SK, JH, MSe, MSc, and MP collected the data. MP, OK, and MSc performed the data extraction and statistical analyses. MP, OK and MSc wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Martin Schuler: Consultancy: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG), Lilly, Novartis; honoraria for CME presentations: Alexion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Novartis; research funding to institution: Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis; other: Universität Duisburg-Essen (patents). Martin Metzenmacher: honoraria: Astra Zeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer Roche, Sanofi Aventis. Marcel Wiesweg: honoraria: Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Roche, Takeda. Research. Stefan Kasper: consultancy, honoraria and travel support: Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Amgen, Merck Serono, Sanofi Aventis, Astra Zeneca, Janssen, Pharmaceuticals, Celgene, Lilly, and Servier. Michael Pogorzelski: consultancy, honoraria, and travel support: Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Healthcare KGaA, Merck Sharp, and Dohme, Takeda. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval, consent to participate, consent to publish

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Medical Faculty of the University Duisburg-Essen and University of Frankfurt in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration (Decision number: 19–8585-BO).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kraskowski, O., Stratmann, J.A., Wiesweg, M. et al. Favorable survival outcomes in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutant non-small cell lung cancer sequentially treated with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor and osimertinib in a real-world setting. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 149, 9243–9252 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-023-04839-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-023-04839-3