Abstract

Purpose

Outcomes of multiple myeloma (MM) patients who are refractory to daratumumab are dismal and no standard of treatment exists for this patients’ population. Here, we investigate the role of pomalidomide combinations in daratumumab-refractory MM patients.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of myeloma patients treated at four referral centers (three in Germany and one in Italy). Review chart identified 30 patients with relapsed and refractory myeloma, who progressed during treatment with daratumumab and were treated with pomalidomide-based combinations in the subsequent lines of therapy.

Results

Responses improved from 37% with daratumumab to 53% with pomalidomide. Of seven patients with extramedullary MM (EMM), four achieved a clinical stabilization with pomalidomide, including one patient with a long-lasting complete response. Median progression-free survival and overall survival were 6 and 12 months, respectively. Pomalidomide combinations were well tolerated, no patient discontinued treatment due to adverse events.

Conclusion

These data show that pomalidomide-based combinations can be an effective and safe salvage regimen for daratumumab-refractory patients, including those with EMM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the past decades, considerable advances have been made in the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM). The anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab has shown remarkable activity in relapsed as well as in newly diagnosed MM patients and is now one of the preferred regimens both in the first line and at the time of relapse (Lonial et al. 2016; Palumbo et al. 2016; Dimopoulos et al. 2016, 2020; Facon et al. 2019; Moreau et al. 2019). Due to its recent approval and wide application, however, little is known about the best salvage treatment for patients who progress on daratumumab. Recent data indicate that outcome after relapse to daratumumab treatment is dismal (Gandhi et al. 2019), with a median overall survival (OS) shorter than 1 year. Survival is even worse for those patients refractory to an immunomodulator (IMiD), a proteasome inhibitor (PI), and a CD38 monoclonal antibody (triple refractory patients) (Mateos et al. 2022) and for those patients already exposed to two IMiDs, two PIs, and a CD38 monoclonal antibody (penta-exposed patients) (Gandhi et al. 2019). Pomalidomide is a third-generation IMiD approved for treatment of relapsed MM patients that have already been treated with lenalidomide and a PI. Pomalidomide alone and especially in combination has shown efficacy in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) patients (San Miguel et al. 2013; Larocca et al. 2013; Dimopoulos et al. 2018; Richardson et al. 2019; Van Oekelen et al. 2020). The fact that pomalidomide is well tolerated in elderly and frail patients (Larocca et al. 2013), is important as patients with advanced disease frequently present in poor clinical condition. Here, we investigated the use of pomalidomide combinations in a cohort of patients progressing during daratumumab treatment to evaluate the role of pomalidomide combinations in this challenging patient population.

Methods

Clinical records of patients treated at four University Hospitals, three in Germany (Jena, Halle and Freiburg), and one in Italy (Bologna), from 2016 to 2019, were analyzed retrospectively. All patients were followed until death or last follow-up, whichever occurred first. Patients lost to follow-up were censored at the date of the last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) and OS were evaluated from the start of pomalidomide-based treatments using the Kaplan–Meier method. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS, version 24. The study was approved by the institutional review boards.

Results

Thirty pomalidomide-naïve patients treated with pomalidomide-based combinations after being refractory to daratumumab were identified. In 24 patients, pomalidomide was the first treatment administered after progression on daratumumab, while the remaining patients received one (five patients) to two (one patient) lines of therapy between daratumumab and pomalidomide. Patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients were heavily pretreated, with a median time between diagnosis and pomalidomide treatment of 5.5 years (range 1–17), and a median number of 4 previous lines of treatment (range 2–12). All patients were refractory to daratumumab. Twenty-three (77%) and sixteen out of thirty patients (53%) were refractory to IMiDs and PIs, respectively. Thirteen (43%) and five (16%) were triple refractory and penta exposed, respectively. Autologous stem cell transplantation had been performed in 23/30 (77%) patients, and 5/30 patients had also received an allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Seven patients had an extramedullary disease (EMM) at the time of pomalidomide treatment. Median number of cycles of daratumumab administered before receiving pomalidomide-based treatment was 4 (range 1–18). Responses to daratumumab were challenging in this intensively pretreated population: 27% of patients achieved a partial response (PR), 10% a very good PR (VGPR) and 17% had a stable disease (SD). No patient achieved a complete response (CR) and 43% were primary refractory.

Most patients received pomalidomide as part of a triplet combination. The drugs most frequently combined with pomalidomide were dexamethasone (29 cases) and cyclophosphamide (16 cases) (Garderet et al. 2018). Other combinations included elotuzumab (five cases) or PIs (two cases bortezomib, two cases carfilzomib, one case ixazomib). Three patients were treated only with the doublet pomalidomide/dexamethasone and one patient received pomalidomide monotherapy. No patient received daratumumab in combination with pomalidomide, as the combination of daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone was not approved at the time. The median daily dose of pomalidomide was 4 mg (range 1–4) and the median monthly dose of dexamethasone was 80 mg (range 0–480 mg). For patients receiving cyclophosphamide, the median monthly dose of cyclophosphamide was 900 mg (range 150–1800 mg). The overall response rate [≥ PR] (ORR) was 53%, with 2/30 and 3/30 patients achieving a CR and a VGPR, respectively. The disease control rate (DCR ≥ SD) was 83% (25/30 patients) (Supplementary Table 1). In those patients receiving pomalidomide combinations as first regimen after daratumumab failure, the ORR was 54% (13/24). Of the seven patients presenting with EMM, four out of seven achieved disease control (≥ SD), including three patients with a PR and one patient with a CR that lasted for more than 2 years. DCR for EMM patients increased from 28% (two out of seven patients) with daratumumab therapy to 86% (six out of seven patients) with pomalidomide combinations (Supplementary Table 2).

Responses to pomalidomide combinations were achieved promptly, with 60% of the patients responding within the first two cycles.

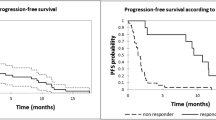

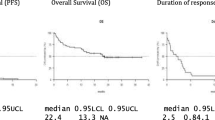

With a median follow-up of 13 months (95% CI 3.3–22.7), the median PFS was 6 months (95% CI 3.4–8.5) and the median OS was 12 months (95% CI 3.3–20.7) (Fig. 1A and 1B).

Pomalidomide combinations were well tolerated. Neutropenia ≥ grade 3 was reported in five patients, of which only one developed a neutropenic fever. Two patients received prophylactic G-CSF. Two patients had a thrombocytopenia ≥ grade 3 and three patients had a grade 3 anemia. The most frequent non-hematologic adverse events (AEs) of grade ≥ 3 were infections (three pneumonia and two sepsis). Dose reductions due to AEs occurred in five patients, of which four dose-reduced pomalidomide.

Discussion

The overall prognosis for patients with MM relapsing after salvage therapy with daratumumab appears disheartening (Gandhi et al. 2019). New treatment options are now available for these patients, including BCMA-immunoconjugates (Lonial et al. 2019), selinexor (Chari et al. 2019), CAR-T cells (Munshi et al. 2021; Berdeja et al. 2021), and bispecific antibodies (Moreau et al. 2022; Chari et al. 2022). Nevertheless, not all these treatments are widely available across countries or can be applied to all patients. Additionally, extensively treated RRMM often has an aggressive biology requiring combination therapy. Pomalidomide, a third-generation IMiD, is approved together with dexamethasone and can be applied in a variety of combinations for the treatment of RRMM. We here investigated the effect of pomalidomide-based regimens in patients refractory to daratumumab after a median of 4 lines of therapy. Overall, pomalidomide combinations were well tolerated and showed a significant response rate of 53% in this difficult-to-treat population. In comparison, Gandhi and colleagues reported an ORR of 31% to the first regimen given after daratumumab failure, identifying carfilzomib-based regimens and daratumumab plus IMiDs as treatments significantly associated with a longer PFS (Gandhi et al. 2019). More recently, the LocoMMotion study, a prospective, non-interventional, multinational study to assess the effectiveness of real-life standard of care treatments in triple-class exposed MM patients showed a median PFS of 4.6 months with a median OS of 12.4 months after diagnosis of the most recent relapse. Among the 248 patients enrolled, the ORR was 30%, with 12% of VGPR and only 1 patient achieving a CR (Mateos et al. 2022). Despite the limitation of a much smaller patients’ population and of the retrospective nature of our study, our results compare favorably with these data. Importantly, the LocoMMotion study showed that no standard treatment exists for triple-exposed RRMM patients, with 92 different combinations being reported in the trial, once more highlighting the unmet medical need of MM patients beyond the third line of therapy.

Among agents with a novel mechanism of action, selinexor (Chari et al. 2019) and belantamab-mafodotin (Lonial et al. 2019) have been reported to yield ORR between 26 and 30% in RRMM after failure of daratumumab. Due to the significantly different number of patients and the different trial design, no definitive conclusion can be drawn on what should be the preferred treatment regimen for patients refractory to daratumumab. Importantly, a recent phase 3 study failed to show a superiority of belantamab-mafodotin compared to pomalidomide in RRMM patients (GSK GmbH DREAMM-3 Announcement). CAR-T cells are highly effective, but their applicability is restricted to a limited number of patients. Similarly, bispecific antibodies require hospitalization for at least the first four doses. More than 90% of our study population had been exposed to IMiD or PI, with 43% of patients being triple refractory. Although the small number of patients prevented us from performing subgroup analyses, pomalidomide combinations were effective in this difficult-to-treat population, with a rate of disease control (at least SD) of 83%. Importantly, pomalidomide combinations were effective even in patients with extramedullary myeloma (EMM), with five out of seven patients with EMM achieving at least a clinical stabilization including one patient with a CR that lasted for more than 2 years (Supplementary Table 1).

At the time of treatment of our patients (between 2016 and 2019), the combination of pomalidomide, daratumumab, and dexamethasone was not approved in Europe and no patient in our cohort received treatment with pomalidomide combined with an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody. Data from the Emory group on a limited number of patients showed that retreatment with daratumumab in combination with pomalidomide and dexamethasone can still be effective in patients that are daratumumab refractory (Nooka et al. 2019), suggesting that combining pomalidomide with an anti-CD38 antibody can add another treatment option for these patients.

In line with other reports (Larocca et al. 2013; Dimopoulos et al. 2018; Nooka et al. 2019), pomalidomide combinations were well tolerated, with AEs of grade ≥ 3 reported only in 17% of the patients. Hematologic adverse events were manageable, with only two patients receiving prophylactic G-CSF to maintain a neutrophil count above 1000/mm3. No patient had to discontinue treatment due to AEs.

Median PFS and OS compared well with those reported by MAMMOTH (Gandhi et al. 2019) and by the LocoMMotion (Mateos et al. 2022) studies, with 6 months and 12 months, respectively. Due to the limited number of patients included in this retrospective analysis, no further evaluation of the impact of high-risk cytogenetic profile or of the impact of EMM could be performed.

Although with the limitation of a small number of patients and the retrospective nature of our analysis from four large MM institutions, these data suggest that pomalidomide combinations are a helpful option for patients after several lines of therapy and refractory to daratumumab treatment. This concept is also illustrated by the various pomalidomide combinations recently approved, as well as the various combinations of pomalidomide with novel agents and immunotherapeutic approaches still under investigation in clinical trials. Due to the widespread use of daratumumab in all lines of therapy, the number of patients in this clinical situation is likely to increase. Here, treatment with a pomalidomide-containing combination is a well-tolerated option with beneficial efficacy. In the future, combinations of pomalidomide and drugs with a novel mechanism of action, such as bispecific antibodies, BCMA-immunoconjugates or selinexor may further improve patient outcome. Final data of ongoing studies with these combinations (NCT04484623, NCT02343042) are eagerly awaited and might change the treatment paradigm of RRMM patients.

In summary, pomalidomide-based treatment is a safe and effective option for patients refractory to daratumumab, supporting the use of these regimens as salvage treatment even in late lines of therapy.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this paper are available from the corresponding author, AB, upon reasonable request.

References

Berdeja JG, Madduri D, Usmani SZ et al (2021) Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet 398:314–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00933-8

Chari A, Vogl DT, Gavriatopoulou M et al (2019) Oral selinexor-dexamethasone for triple-class refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 381:727–738. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1903455

Chari A, Minnema MC, Berdeja JG et al (2022) Talquetamab, a T-cell–redirecting GPRC5D bispecific antibody for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 387:2232–2244. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2204591

Dimopoulos MA, Oriol A, Nahi H et al (2016) Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 375:1319–1331. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1607751

Dimopoulos MA, Dytfeld D, Grosicki S et al (2018) Elotuzumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1805762

Dimopoulos M, Quach H, Mateos M-V et al (2020) Carfilzomib, dexamethasone, and daratumumab versus carfilzomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CANDOR): results from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 396:186–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30734-0

Facon T, Kumar S, Plesner T et al (2019) Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone for untreated myeloma. N Engl J Med 380:2104–2115. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1817249

Gandhi UH, Cornell RF, Lakshman A et al (2019) Outcomes of patients with multiple myeloma refractory to CD38-targeted monoclonal antibody therapy. Leukemia 33:2266–2275. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0435-7

Garderet L, Kuhnowski F, Berge B et al (2018) Pomalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. Blood 132:2555–2563. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-07-863829

GSK GmbH DREAMM-3 Announcement GSK provides an update on Blenrep (belantamab mafodotin-blmf) US marketing authorisation | GSK. In: GSK Belantamab Mafodotin Statment. https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/gsk-provides-update-on-blenrep-us-marketing-authorisation/. Accessed 31 Jan 2023

Larocca A, Montefusco V, Bringhen S et al (2013) Pomalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: a multicenter phase 1/2 open-label study. Blood 122:2799–2806. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-03-488676

Lonial S, Weiss BM, Usmani SZ et al (2016) Daratumumab monotherapy in patients with treatment-refractory multiple myeloma (SIRIUS): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet 387:1551–1560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01120-4

Lonial S, Lee HC, Badros A et al (2019) Belantamab mafodotin for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (DREAMM-2): a two-arm, randomised, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30788-0

Mateos M-V, Weisel K, De Stefano V et al (2022) LocoMMotion: a prospective, non-interventional, multinational study of real-life current standards of care in patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia 36:1371–1376. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-022-01531-2

Moreau P, Attal M, Hulin C et al (2019) Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. The Lancet 394:29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31240-1

Moreau P, Garfall AL, van de Donk NWCJ et al (2022) Teclistamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 387:495–505. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2203478

Munshi NC, Anderson LD, Shah N et al (2021) Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 384:705–716. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2024850

Nooka AK, Joseph NS, Kaufman JL et al (2019) Clinical efficacy of daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory myeloma: utility of re-treatment with daratumumab among refractory patients. Cancer 125:2991–3000. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32178

Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K et al (2016) Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 375:754–766. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1606038

Richardson PG, Oriol A, Beksac M et al (2019) Pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma previously treated with lenalidomide (OPTIMISMM): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 20:781–794. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30152-4

San Miguel J, Weisel K, Moreau P et al (2013) Pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone versus high-dose dexamethasone alone for patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (MM-003): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 14:1055–1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70380-2

Van Oekelen O, Parekh S, Cho HJ et al (2020) A phase II study of pomalidomide, daily oral cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma 61:2208–2215. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2020.1805111

Acknowledgements

AB was supported by the grant Förderung von Frauen in der Wissenschaft of the IZKF (Interdisziplinäre Zentrum für Klinische Forschung) at Jena University Hospital, Jena, Grant FF04 and is an Alumna of the Else Kröner Forschungskolleg AntiAge at Jena University Hospital. MvLT receives support from the German Research Foundation within the Collaborative Research Centre/Transregio 124 FungiNet, DFG project no. 210879364 (project A1) as well as from the Deutsche Krebshilfe OncoReVir Registry (No. 70113851)

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB and MvLT designed the research; AB, LG, KM, MB, TE, FH, TS, EZ, IH, AH, ME, and MvLT treated the patients and provided patients data; AB wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all the authors contributed to the manuscript editing, read and approved the last version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

AB has participated in advisory boards from BMS/Celgene, Janssen, GSK, Takeda, and Sanofi and received honoraria and travel support from BMS/Celgene, Janssen, GSK, Sanofi, AMGEN, Gilead, and Takeda; KM has received honoraria from BMS/Celgene, Janssen, Amgen, Takeda, Pfizer, GSK, and Sanofi; MB has received honoraria from BMS/Celgene; FHH has received research funding from BMS/Celgene and served as an advisor for BMS/Celgene and Janssen; TS has participated in advisory boards from Novartis, has received honoraria from Novartis, Amgen, Alexion, Janssen, AOP, BMS, Grifols and has received research support from Novartis, Amgen, Sobi, Argenx, and Grifols; EZ has received honoraria and is an advisory board member for BMS/Celgene, Janssen, Amgen, Sanofi, GSK; AH received research support by Novartis, BMS/Celgene, Pfizer, and Incyte; MvLT has received honoraria from Celgene, Gilead, Chugai, Janssen, Novartis, Amgen, Takeda, BMS, Medac, Oncopeptides, Merk, CDDF, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Thermofisher, GSK, and Shionogi and research funding from BMBF, Deutsch José Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung, IZKF Jena, DFG, Novartis, Gilead, Deutsche Krebshilfe, BMS/Celgene, Oncopeptides. All the other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brioli, A., Gengenbach, L., Mancuso, K. et al. Pomalidomide combinations are a safe and effective option after daratumumab failure. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 149, 6569–6574 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-023-04637-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-023-04637-x