Abstract

Purpose

Mistletoe treatment is discussed controversial as a complementary treatment for cancer patients. Aim of this systematic analysis is to assess the concept of mistletoe treatment in the clinical studies with respect to indication, type of mistletoe preparation, treatment schedule, aim of treatment, and assessment of treatment results.

Methods

In the period from August to December 2020, the following databases were systematically searched: Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PsycINFO, CINAHL, and “Science Citation Index Expanded” (Web of Science). We assessed all studies for study types, methods, endpoints and mistletoe preparations including their ways of application, host trees and dosage schedules.

Results

The search concerning mistletoe therapy revealed 3296 hits. Of these, 102 publications and at total of 19.441 patients were included. We included several study types investigating the application of mistletoe in different groups of participants (cancer patients of any type of cancer were included as well as studies conducted with healthy volunteers and pediatric patients). The most common types of cancer were breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer and malignant melanoma. Randomized controlled studies, cohort studies and case reports make up most of the included studies. A huge variety was observed concerning type and composition of mistletoe extracts (differing pharmaceutical companies and host trees), ways of applications and dosage schedules. Administration varied e. g. between using mistletoe extract as sole treatment and as concomitant therapy to cancer treatment. As the analysis of all studies shows, there is no relationship between mistletoe preparation used, host tree and dosage, and cancer type.

Conclusions

Our research was not able to deviate transparent rules or guidelines with respect to mistletoe treatment in cancer care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Mistletoe extracts are used in cancer patients either as sole alternative therapy or commonly as complementary treatment in addition to conventional cancer therapy (Ebel et al. 2015; Huebner et al. 2014).

Mistletoe (Viscum album) is a small plant growing as a hemiparasite on several types of host trees in Europe, Asia and North Africa (Becker 1986). Mistletoe host trees include, for example fir (Abietis), maple (Aceris), almond (Amygdali), birch (Betulae), hawthorn (Crategi), ash (Fraxini), apple tree (Mali), pine (Pini), poplars (Populi) and oak (Quercus).

Two different groups of mistletoe preparations exist. Phytotherapeutic mistletoe preparations which are applied at a constant dose of lektines (Cefalektin®, Eurixor® and Lektinol®) and anthroposophical or homeopathically produced mistletoe preparations (Helixor®, Iscador®, Abnobaviscum®, Iscucin®, Isorel® and Plenosol®) are used in cancer treatment (Lange-Lindberg et al. 2006). In the second group, the dose of mistletoe preparation should be increased continuously depending on the general condition of the patient, the extent of the local reaction at the injection site and the regulation of body temperature (Horneber et al. 2008). According to the recommendations of the manufacturers, the preparations should usually be administered two to three times a week by subcutaneous injection in increasing dosages (Horneber et al. 2008). Mistletoe extracts are also increasingly administered intravenously, intratumorally, or intracavitarily (Kienle and Kiene 2007). These ways of application are off-label injections.

The various viscum extracts differ in their composition of the individual components (viscotoxins, lectins, polysaccharides, flavonoids, triterpenes and polypeptides), as well as the time of harvesting and different production processes (Holandino et al. 2020; Horneber et al. 2008; Nazaruk and Orlikowski 2016).

In cancer therapy, there are two discussed theses on mistletoe’s mode of clinical relevant action: First, some authors postulate that mistletoe extracts have a cytostatic, i.e., growth-inhibiting, and immunomodulating effect, i.e., immune system-stimulating effect via cytotoxic substances or via lectins (Boneberg and Hartung 2001; Felenda et al. 2019; Gardin 2009; Hajtó et al. 2005; Hostanska et al. 1995; Huber et al. 2006; Hulsen et al. 1989; Jurin et al. 1993; Klingbeil et al. 2013; Menke et al. 2019, 2020; Seifert et al. 2008; Tabiasco et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2019). Second, some authors say that mistletoe improves well-being and quality of life and reduces side effects related to conventional cancer treatment (Beuth et al. 2008; Bussing et al. 2012; Cazacu et al. 2003; Eisenbraun et al. 2011; Horneber et al. 2008; Kienle and Kiene 2010; Kim et al. 2012; Lange-Lindberg et al. 2006; Loef and Walach 2020; Loewe-Mesch et al. 2008; Pelzer et al. 2022; Piao et al. 2004; Semiglazov et al. 2006), possibly triggered by the release of endorphins (Heiny and Beuth 1994; Lenartz et al. 1999).

The benefit of mistletoe treatment is still discussed and highly controversial. There are systematic reviews supporting the thesis that mistletoe extracts can improve quality of life in general (Bussing et al. 2012; Horneber et al. 2008; Loef and Walach 2020; Melzer et al. 2009), in breast cancer patients (Kienle et al. 2009; Kienle and Kiene 2010; Lange-Lindberg et al. 2006) and in patients with gynaecological cancer (Kienle et al. 2009). In the study of Pelzer et al. (2022) only a moderate effect on cancer-related fatigue of similar size as physical activity was reported. Other authors attribute a positive benefit to mistletoe therapy in terms of survival (Ostermann et al. 2009, 2020) and toxicity of the main intervention (Kienle et al. 2009). However, some of these reviews have a high risk of bias and heterogeneity (Loef and Walach 2020; Ostermann et al. 2020). In contrast, Horneber et al. (2008) and Lange-Lindberg et al. (2006) concluded that the available evidence from the included studies was insufficient to prove efficacy of mistletoe treatment regarding survival and reduction of the toxicity of chemotherapeutic treatment. In addition, Freuding et al. (2019a, b) also concluded that in terms of survival, quality of life or reduction of treatment-related side effects, there is no indication to prescribe mistletoe to patients with cancer. In the statement of Matthes et al. (2020), a retraction of the two-part review of Freuding et al. (2019a, b) is demanded due to a lack of methodological quality. According to the current German S3-Guideline on complementary medicine in the treatment of oncological patients, the administration of mistletoe preparations is controversial due to heterogeneous systematic reviews (Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie:Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF 2021).

In all these discussions, mistletoe is regarded as a concise treatment concept. So far, literature did not consider the different mistletoe preparations and treatment schedules. However, comparability between type of drug, applications and treatment schedules should be regarded as base for systematic reviews as well as meta-analyses while deliberating the role of mistletoe treatment in modern oncology.

Objectives

Aim of this systematic analysis is assess the concept of mistletoe treatment in the clinical studies with respect to indication, type of mistletoe preparation, treatment schedule, aim of treatment, and assessment of treatment results.

Methods

Criteria for including studies in this review

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in supplementary file 2 (Table e1). We included cancer patients as well as studies with healthy persons which assessed endpoints regarded as relevant for mistletoe treatment in cancer care (for example immunological parameters).

Search strategy

In the period from August to December 2020, the following databases were systematically searched: Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PsycINFO, CINAHL, and “Science Citation Index Expanded” (Web of Science). A complex search string was developed for each database. This contained a combination of mesh terms/keywords and text words related to cancer and mistletoe. To make sure that no study would be missed, the search was not limited by filters for study type. Only articles published in English or German were considered. The exact search strategy with the respective applied mesh terms/keywords and text words for each database is shown in supplementary file 3 (Table e2, Freuding et al. 2019a, b).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Study selection of this review was made in several steps

First, titles and abstracts of all clinical and preclinical studies with descriptions of the respective study population, mistletoe preparation (name and dosage), endpoints and results were collected in a table and screened for relevance to this review by two independent reviewers (HS, JH). Reasons for rejecting studies were irrelevant topics, studies with other anthroposophic study medications than mistletoe preparations and studies no endpoint associated with cancer of cancer treatment.

Second, all articles were excluded that were not scientific articles published as full papers in a peer-reviewed journal.

After that, full texts from all remaining studies were screened and again it was decided by two independent reviewers (HS, JH) if they matched with inclusion criteria (see supplementary file 2, Table e1).

All excluded studies are characterized in the section “Excluded studies”.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was done by HS and controlled by JH independently. In case of disagreement, consensus was made by discussion.

Assessment of study endpoints

We analyzed all endpoints from the extraction sheet and summarized them into ten categories listed in supplementary file 4 (Table e3).

Results

The search concerning mistletoe therapy revealed 3296 hits. Of these, 1157 duplicates were removed. After title-abstract-screening 639 studies remained, including 290 clinical and 381 preclinical studies. After fulltext-screening 102 clinical publications reporting data from 108 different clinical studies remained and underwent further investigation (see supplementary file 1, Fig. e1).

Characteristics of included studies

Heterogeneity of included study populations

Overall, 19.441 patients from 108 studies were included in this review (missing data on included patients in the publication of Majewski and Bentele (1963), therefore not included in the total number of included patients). Of these, 18.176 patients were analyzed. The study populations were very heterogeneous. Three of the included studies were conducted with pediatric patients (Cho and Kim 2018: n = 1; Seifert et al. 2007: n = 1; Zuzak et al. 2018: n = 10). Healthy subjects were investigated in three studies (Gorter et al. 1998: n = 7; Huber et al. 2002: n = 48, 2011: n = 71). Due to the large heterogeneity of the included patients in terms of variation in patient characteristics, comparability of the different studies among themselves is limited.

Great heterogeneity in study designs used for clinical trials

The included studies show a variety of different study designs (see supplementary file 5, Table e4). In one study, the study type is not specified (Gorter et al. 1998). Two of the studies are feasibility studies (Gaafar et al. 2014; Loewe-Mesch et al. 2008). The 36 cohort studies can be divided into controlled and non-controlled studies. Of these, 29 studies (16 publications respectively) are designed as controlled studies (Augustin et al. 2005; Bock et al. 2004a, 2014; Beuth et al. 2008; Friedel et al. 2009; Grossarth-Maticek and Ziegler 2006a, b, 2007a, b, 2007c, 2008; Matthes et al. 2010; Schumacher et al. 2003; Thronicke et al. 2017, 2020a; Zaenker et al. 2012) Of the studies published by Grossarth-Maticek, eight were randomized matched-pair studies, and eleven were non-randomized matched-pair studies. The remaining cohort studies are non-controlled (Brandenberger et al. 2012; Oei et al. 2019a, b; Schad et al. 2017, 2018a, b; Thronicke et al. 2020b). There is a big heterogeneity regarding study designs and thus also a divergence in terms of level of evidence and methodological quality of the included studies. Thus, an evaluation and assessment regarding the effect of mistletoe therapy becomes difficult.

Huge variety in cancer types investigated in clinical trials

The most common types of cancer included in this review were breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer and malignant melanoma. A more detailed overview is shown in supplementary file 6 (Table e5). In three studies, healthy volunteers were recruited (Gorter et al. 1998: number of patients included (nI) = 7, number of patients analyzed (nA) = 7; Huber et al. 2002: nI = 48, nA = 48; Huber et al. 2011: nI = 71, nA = 71). In the included studies, mistletoe therapy is used in patients with a variety of different cancer types. Thus, comparability of the studies is limited.

Great variety in mistletoe preparations used for clinical trials

Anthroposophical or homeopathically produced mistletoe preparations (Helixor®, Iscador®, Abnobaviscum®, Iscucin®, Isorel®, Plenosol® and Viscum mali e planta tota®) as well as phytotherapeutic mistletoe preparations (Eurixor® and Lektinol®) were used in the studies. In 75 studies, only one mistletoe preparation was used. In ten studies, mistletoe preparations from different host trees were used, but mistletoe preparations had been obtained from the same pharmaceutical company. In the remaining 20 studies two or more different mistletoe preparations were tested.

In some studies, the authors only reported that patients received mistletoe extracts and the mistletoe preparation was not specified (Elsasser-Beile et al. 2005a; Hwang et al. 2019; Oh 2020; Werthmann et al. 2017a, 2018c). In another study, it was only reported that patients received mistletoe lectin (Goebell et al. 2002). Moreover, in some studies Viscum-fraxini-2® was given as study medication (Ebrahim et al. 2010; El-Kolaly et al. 2016; Gaafar et al. 2014; Mabed et al. 2004). In three of these studies, the pharmaceutical company was not explicitly mentioned (Ebrahim et al. 2010; Gaafar et al. 2014; Mabed et al. 2004). Thus it was not clear from which pharmaceutical company the preparation was delivered and in the study of Gaafar et al. (2014) which dosage was used.

Supplementary file 7 (Table e6) shows the mistletoe preparations used in relation to the different types of cancer.

In two of studies with healthy volunteers, Iscador® preparations such as Iscador® QuFrF (n = 4) or Iscador® Qu Spezial (n = 3) [N = 7, Gorter et al. (1998)] and Iscador® Qu Spezial (n = 16) or Iscador® P (n = 16) [N = 32, Huber et al. (2002)] were used. In the third study, Iscucin® Populi and Viscum mali e planta tota® which is usually used in patients with anthropathies were used as study medications [N = 30, Huber et al. (2011)].

A variety of different mistletoe preparations was used to treat cancer patients. Due to the heterogeneity of the mistletoe preparations used, no relationship between mistletoe preparation and type of cancer can be observed.

Different ways of application of mistletoe preperations

Mistletoe preparations are approved for subcutaneous application. Accordingly, in most of the studies, VAE was applied subcutaneously. In 63 studies, subcutaneous injections was the only way of application. In contrast, in 17 studies s.c. application and at least one other application form was used. Other common forms of mistletoe application were off-lable intratumoural or intravenous injections. Rare forms of application were intrapleural, intraperitoneal, intravesical, intrathecal or oral. In nine studies, the form of application was not specified. Despite the only approval of mistletoe preparations for subcutaneous applications, mistletoe preparations were applied off-label in many different other ways.

Great variety of dosage and dosage schedules used in clinical trials

The dosage of the mistletoe preparations varied greatly (see supplementary file 8, Table e7). In some studies, the dosage of the mistletoe preparations used was not specified. In other studies, however, only an average or median dosage was given (Bock et al. 2004a, 2014; Schläppi et al. 2017; Zaenker et al. 2012). There is a big heterogeneity regarding the dosages and dosage schedules. In many studies, the dosage schedules for subcutaneous application deviate from the recommendations of the respective manufacturers. Also, the dosage schedules used for off-label injections, for which no dosage recommendations exist, varies greatly.

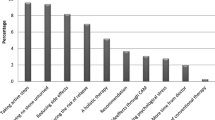

Heterogeneity of indications for usage of mistletoe and endpoints assessed

Across the studies, outcome parameters varied considerably. All in all, the endpoints may be sorted in ten categories which are listed in supplementary file 9 (Table e8). including the respective studies. The heterogeneity of the indications of mistletoe in the studies points to a lack of defined indications and aims in mistletoe treatments.

Excluded studies

Four double publications published in German as well as in English were excluded (Lenartz et al. 2000, 2001; Piao et al. 2004; Schierholz et al. 2003; Tröger et al. 2009; Tröger et al. 2011; Schumacher et al. 2002, 2003).

Apart from that, two other publications were excluded because they were reporting almost completely overlapping data from the same study (Bock et al. 2004a, b; Elsasser-Beile et al. 2005a, b).

Besides that, two randomized datasets based on patients with breast cancer or different cancer types were excluded (Grossarth-Maticek et al. 2001). The first dataset studying breast cancer patients was re-analyzed in a later publication which is included in this review instead (Grossarth-Maticek and Ziegler 2006b). The other randomized dataset based on various cancer types was excluded. As it is not clear to what extent the data overlap with subsequent studies (Grossarth-Maticek and Ziegler 2007b, 2007c, 2008).

Finally, another publication was excluded because it reported preliminary results from a study published later (Longhi et al. 2009, 2014).

Discussion

We analyzed 108 clinical studies, comprising 19.441 participants including healthy volunteers and pediatric patients in three studies each. The studies comprise nine different mistletoe preparations in various dosages and eight different ways of application. In the studies by Grossarth-Maticek et al., it may not be excluded that data from control patients were used more than once, as in the articles it is said that „control patients were only used once in the mistletoe studies and were never used in other studies”, which does not exclude the same patients being used as control in several mistletoe studies.

Less than one third of the included 108 studies were randomized controlled studies showing a formally high level of evidence. However, even these studies lack methodological quality. The study of Cho et al. 2016 that was named a phase III trial but was conducted as a single-armed study including no control group. The argumentation of the authors that a control group was not possible due to a lack of a standard treatment in pleurodesis is not correct. Talkum as well as bleomycin would have been well established options (Ried and Hofmann 2013).

Another 22 of the included studies are case reports or case series with the lowest level of evidence and thus little informative value with regard to the safety and efficacy of mistletoe therapy.

Anthroposophical or homeopathically produced mistletoe preparations (Helixor®, Iscador®, Abnobaviscum®, Iscucin®, Isorel®, Plenosol® and Viscum mali e planta tota®) as well as phytotherapeutic mistletoe preparations (Eurixor® and Lektinol®) were used in the studies. They were applied subcutaneously, intravenously and intratumorally.

All in all, it can be concluded that there is a considerable heterogeneity with respect to different study populations, study types, mistletoe preparations, ways of application and dosage schedules as well as various endpoints. The application of mistletoe preparations does not seem to follow any transparently defined plan with respect to types of mistletoe, type of preparation or schedule of administration. In most studies, the positive effects in terms of survival, tumor response, symptom control, quality of life etc. were attributed to mistletoe therapy. Differences in study concepts and endpoints points to a lack of defined indications and aims in mistletoe treatments in general.

Mistletoe preparations and host trees

A variety of different mistletoe preparations was used to treat cancer patients. Due to the heterogeneity of the mistletoe preparations used, no comparability between different studies or within single studies using different types of mistletoe preparations or host trees is possible. Moreover, no relationship between mistletoe preparation and type of cancer can be observed. This results in a severely limited comparability of studies with regard to the different cancer entities and mistletoe therapy in oncology in general.

Analyzing the methods sections of all articles, there are no information on how the selection of the respective mistletoe preparation took place. None of the articles provided any argument which type of preparation (homeopathic, anthroposophic, standardized) or which host tree was chosen due to which selection criteria. Considering preparations from different companies, funding may have been the reason of the selection. For example, all studies by Grossarth–Maticek used Iscador®.

In breast cancer patients for example, six different mistletoe preparations including AbnobaViscum®, Helixor®, Iscador®, Eurixor®, Iscucin® and Lektinol® from three different host trees (abietis, mali and pini). Yet, only in six studies information on host trees was given. In only three studies, mistletoe preparations from different pharmaceutical companies were used (Oei et al. 2018, 2019a; Pelzer et al. 2018; Tröger et al. 2009, 2012, 2014b, 2016) and moreover, in only one study, patients were treated with a mistletoe preparation from one company grown on different host trees (Beuth et al. 2008). In case of pancreatic cancer five different mistletoe preparations including AbnobaViscum®, Isador®, Helixor®, Eurixor® and Iscucin® from seven different host tress (abietis, aceris, mali, pini, fraxini, quercus and salicis) were used and in only two studies, the patients received different mistletoe preparations from different pharmaceutical companies (Schad et al. 2014; Werthmann et al. 2018b). In two studies mistletoe preparations from the same preparation type, but from different host trees were given (Thronicke et al. 2020a; Werthmann et al. 2019a).

The results are the same for colorectal cancer (three mistletoe preparations from four different host trees, only one study with mistletoe grown on different host trees), malignant melanoma (three mistletoe preparations from five host trees), lung cancer (three mistletoe preparations), renal cell carcinoma (four mistletoe preparations from four host trees, one study with different host trees) or gynecological cancer (two mistletoe preparations from three host trees).

In many studies, the exact information on the host tree is missing (Bock et al. 2004a, Elsasser-Beile et al. 2005a, Eom et al. 2017, 2018, Goebell et al. 2002, Grossarth-Maticek and Ziegler 2006a, 2006b, 2007a, 2007c, 2008, Günczler et al. 1968, Günczler and Salzer 1969, Hwang et al. 2019, Leroi 1977, Majewski and Bentele 1963, Matthes et al. 2010, Oei et al. 2018, 2019a, 2019b, Oh 2020, Schad et al. 2014, 2018a, Son et al. 2010, Thronicke et al. 2020b).

All in all, from the beginning of the studies available in the international literature, information on which type of mistletoe preparation is used for which special cancer situation is missing. Moreover, neither the results from single studies nor a cross referencing from different studies reveals any information that would allow to derive recommendations for indications.

Also in those studies using preparations from different companies or from different host trees no comparison of outcome data with respect to survival, or side effects of cancer therapy is provided (Augustin et al. 2005; Beuth et al. 2008; Brandenberger et al. 2012; Friedel et al. 2009; Kjaer 1989; Oei et al. 2018, 2019a, b; Pelzer et al. 2018; Schad et al. 2014, 2017, 2018a, b; Schläppi et al. 2017; Steele et al. 2014a; Stumpf et al. 2000, 2003; Thronicke et al. 2017, 2018, 2020a, b; Tröger et al. 2009, 2012, 2014b, 2016; Werthmann et al. 2014, 2017a, b, 2018b, c, 2019a) with the exception of Huber et al. (2002, 2011) and Steele et al. (2014b, 2015). Only four studies directly compared at least two different mistletoe preparations regarding safety and efficacy (Huber et al. 2002, 2011; Steele et al. 2014b, 2015). Yet, two of these studies were conducted with healthy subjects and analyzed immunological parameters The studies of Steele et al. include a direct comparison between mistletoe preparations from different pharmaceutical companies and different host trees with respect to the occurrence of adverse drug reactions.

In a three-armed randomized study of Pelzer et al. (2018) safety, impact on disease-free-survival and clinical response of mistletoe in breast cancer patients were evaluated. In the evaluation, the two groups receiving mistletoe preparations were summarized into one group. In fact the same applies to other studies including a three-armed study of Tröger et al. (2012, 2014b, 20162009, ), in which different mistletoe preparations from different pharmaceutical companies or different host trees were given.

Dosage of mistletoe

Dosage or dosage regimens varied strongly in the studies. Due to the heterogeneity of dosage and dosage regimens within studies and between studies of the endpoints the comparability of the different studies is severely limited.

While there are some studies providing no data at all, in case of breast cancer for example, eight different dosages or different dosage regimens were used, for colorectal cancer there are four different dosages or dosage schedules and for lung cancer five different dosages or dosage regimens. Also for dosage, information on how the dosage was selected is missing in the methods or results sections. Moreover, in some studies, mistletoe was applied in schedules with increasing dosage and/or pausing for several days ranging from one week (Wode et al. 2009) to three months (Goebell et al. 2002).

There are only a few studies comparing the different dosages or dosage schedules of mistletoe preparations (Huber et al. 2017; Rose et al. 2015; Schad et al. 2017; Semiglasov et al. 2004; Steele et al. 2014a, b).

The objective of the study of Semiglasov et al. (2004) was to investigate the safety and impact of Lektinol® on quality of life, chemotherapy related side effects and immunological parameters. Lektinol® at concentrations of 10, 30 or 70 ng mistletoe lectin per ml were used. The analysis of GLQ-8 sum and Spitzer’s uniscale resulted in statistically significant effects on quality of life by using the medium dose of Lektinol®. However, no significant differences in favor of the low and high dose could be established. In contrast, no relevant differences in quality of life between treatment groups could be detected measured by the approved EORTC-QLQ-C30 scale. As a phase I study is lacking on any of the mistletoe preparations, systematic information on dosage is missing.

Duration of treatment

Duration of mistletoe treatment varied strongly in the studies ranging from a single dose given on one day to the application of mistletoe preparations for several years. Moreover, the duration of treatment frequently varied within the studies. In these cases, data on mean or median durations partly with data on range of mistletoe treatment were provided (Augustin et al. 2005; Bar-Sela and Haim 2004; Bock et al. 2004a, 2014; Cho et al. 2016; Eom et al. 2018; Friedel et al. 2009; Grossarth-Maticek and Ziegler 2006b, 2007a, 2008; Mabed et al. 2004; Matthes et al. 2010; Oei et al. 2019b; Schad et al. 2018a; Schumacher et al. 2003; Steele et al. 2014a; Stumpf et al. 2000, 2003; Thronicke et al. 2017, 2018; Zaenker et al. 2012; Zuzak et al. 2018). In some studies, patients were treated with mistletoe preparations until death (Friess et al. 1996; Kjaer 1989) or till unacceptable toxicity/ tumor progression occurred or the patient chose to discontinue treatment (Brinkmann and Hertle 2004; Ebrahim et al. 2010; Kleeberg et al. 2004).

Yet, defined durations of treatment or transparent criteria for a decision to stop mistletoe treatment (apart from tumor progression, tumor response, adverse events and private reasons) are mostly lacking. Moreover, in several studies no data on treatment duration was provided (Bar-Sela et al. 2006; Beuth et al. 2008; Cazacu et al. 2003; El-Kolaly et al. 2016; Elsasser-Beile et al. 2005a; Grossarth-Maticek and Ziegler 2006a, 2007b, c; Günczler et al. 1968; Majewski and Bentele 1963; Oei et al. 2019a; Piao et al. 2004; Schad et al. 2014, 2017, 2018b; Schläppi et al. 2017; Seifert et al. 2007; Shaw et al. 2004; Thronicke et al. 2020a).

Comparison of mistletoe with placebo or another active treatment

As mistletoe is well-known by patients and physicians in German speaking countries and the procedure of regular injections, attention by the physician and the patient may induce a strong placebo effect. As patients may show a local immunological reaction, blinding is difficult.

Four studies were conducted as placebo-controlled studies (Huber et al. 2002, 2011; Semiglasov et al. 2004; Semiglazov et al. 2006).

The analysis of Huber et al. (2002) shows that local reactions occurred, regardless of whether they received Iscador® P, Q or placebo. However, local reactions were significantly less frequent in the placebo group. Furthermore, mean subjective tolerability towards the injection of Iscador® P, Q, and placebo was significantly lower in the patients treated with mistletoe preparation. Moreover, eosinophil rate was increased significantly in the patients treated with Iscador® Q, probably related to its high content of lectins. Yet. the authors point to the fact that no deblinding of the assessors happened.

The same concerns on deblinding apply to the study by Semiglasov et al. (2004) and Semiglazov et al. (2006).

Application

In the studies, mistletoe preparations were administered by different ways of application. Most frequently, the probands received mistletoe preparations subcutaneously, as recommended by the manufacturers. The second most common way was intravenous administration of mistletoe preparations. According to the respective manufacturer, this type of application is only recommended for Lektinol® and Eurixor®. The other preparations are given as off-label intravenous applications. Accordingly, no dosage recommendations from the respective manufacturer are available. Only in two studies the dose schedules are mentioned: according to the classical phase I 3 + 3 dose escalation schedule (Huber et al. 2017) or in ratio to the body surface area (Zuzak et al. 2018).

Indication for usage of mistletoe

Across the studies, efficacy is assessed with respect to survival as well as quality of life. From this, it remains unclear whether mistletoe treatment is considered a tumor therapy or a treatment of side effects.

It is most difficult to compare and integrate data of different studies as the both survival as well as quality of life are assessed using different time points and instruments respectively.

For example, in terms of survival, overall survival/ tumor-related survival, disease-free-survival, postrelapse-disease-free-survival, relapses und metastases, recurrence rate, tumor progression/ time-to-tumor-progression, progression-free-survival, tumor response/ tumor remission have been reported.

Improvement if quality of life of patients receiving mistletoe preparations is an aim of mistletoe therapy. As Horneber et al. (2008) already reported, there is a big heterogeneity between the included studies. First of all, quality of life was assessed in different ways using 13 different multidimensional and unidimensional questionnaires. In two studies the patients were additionally interviewed (Brandenberger et al. 2012; Reynel et al. 2020). Due to the fact, that EORTC-QLQ and FACT-G are the only established QoL instruments in cancer research, the informative value of the studies using other QoL instruments is limited. Furthermore, not all of the studies assessing quality of life are designed as controlled studies, making it not able to compare the effect of mistletoe therapy regarding quality of life with a control group (Brandenberger et al. 2012; Friess et al. 1996; Kjaer 1989). Second, in some studies a selection bias is possible due to inhomogenities of baseline uality of life data (Kim et al. 2012; Klose et al. 2003; Semiglasov et al. 2004; Semiglazov et al. 2006). In other studies there is missing information whether study and control groups are comparable in terms of quality of life at baseline (Enesel et al. 2005; Piao et al. 2004).

To summarize, due to the heterogeneity of the endpoints assessing efficacy mistletoe therapy the comparability of the different studies in limited and scientists conducting systematic review and more so meta-analyses face severe problems in data syntheses.

Limitations of this work

There are several limitations of this review. First of all, there is a big heterogeneity of studies included. On the one hand, the strength lies in a broad overview of studies on mistletoe treatment. On the other hand, the power of this review is limited due to a lack of evidence and methodological quality in the majority of the included studies. Moreover, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis because of the heterogeneity of included studies. Only a descriptive overview of the studies could be conducted. Second, the interpretation of data was limited due to the high heterogeneity of patients, endpoints and mistletoe extracts in different dosages and ways of application. Third, only articles published in German or English were included.

Conclusion

Despite a large number of clinical studies and reports, there is a complete lack of transparently reported, structured procedures considering all fields of mistletoe therapy. This applies to type of mistletoe extract, host tree, preparation, treatment schedules as well as indication with respect of type of cancer and the respective treatment aim. All in all, despite several decades of clinical mistletoe research, no clear concept of usage is discernible and, from an evidence-based point of view, there are serious concerns on the scientific base of this part of anthroposophical treatment.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC et al (1993) The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:365–376

Augustin M, Bock PR, Hanisch J, Karasmann M, Schneider B (2005) Safety and efficacy of the long-term adjuvant treatment of primary intermediate to high-risk malignant melanoma (UICC/AJCC stage II and III) with a standardized fermented European mistletoe (Viscum album L.) extract: results from a multicenter, comparative, epidemiological cohort study in Germany and Switzerland. Arzneimittel Forschung Drug Res 55:38–49

Bar-Sela G, Haim N (2004) Abnoba-viscum (mistletoe extract) in metastatic colorectal carcinoma resistant to 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin-based chemotherapy. Med Oncol 21:251–254

Bar-Sela G, Goldberg H, Beck D, Amit A, Kuten A (2006) Reducing malignant ascites accumulation by repeated intraperitoneal administrations of a Viscum album extract. Anticancer Res 26:709–713

Bar-Sela G, Wollner M, Hammer L, Agbarya A, Dudnik E, Haim N (2013) Mistletoe as complementary treatment in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with carboplatin-based combinations: a randomised phase II study. Eur J Cancer 49:1058–1064

Becker H (1986) Botany of European mistletoe (Viscum album L.). Oncology 43:2–7

Beuth J, Schneider B, Schierholz JM (2008) Impact of complementary treatment of breast cancer patients with standardized mistletoe extract during aftercare: a controlled multicenter comparative epidemiological cohort study. Anticancer Res 28:523–527

Bock PR, Friedel WE, Hanisch J, Karasmann M, Schneider B (2004a) Efficacy and safety of long-term complementary treatment with standardized European mistletoe extract (Viscum album L.) in addition to the conventional adjuvant oncologic therapy in patients with primary non-metastasized mammary carcinoma. Results of a multi-center, comparative, epidemiological cohort study in Germany and Switzerland. Arzneimittelforschung 54:456–466

Bock PR, Friedel WE, Hanisch J, Karasmann M, Schneider B (2004b) Retrolective, comparative, epidemiological cohort study with parallel groups design for evaluation of efficacy and safety of drugs with “well-established use.” Forsch Komplement Und Klass Naturheilkunde [res Complement Nat Class Med] 11(Suppl 1):23–29

Bock PR, Hanisch J, Matthes H, Zanker KS (2014) Targeting inflammation in cancer-related-fatigue: a rationale for mistletoe therapy as supportive care in colorectal cancer patients. Inflam Allergy Drug Targ 13:105–111

Boneberg EM, Hartung T (2001) Mistletoe lectin-1 increases tumor necrosis factor-alpha release in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated whole blood via inhibition of interleukin-10 production. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 298:996–1000

Brandenberger M, Simoes-Wust AP, Rostock M, Rist L, Saller R (2012) An exploratory study on the quality of life and individual coping of cancer patients during mistletoe therapy. Integr Cancer Ther 11:90–100

Brinkmann OA, Hertle L (2004) Combined cytokine therapy vs mistletoe treatment in metastatic renal cell cancer. Clinical comparison of therapy success with combined administration of interferon-alpha2b, interleukin-2, and 5-fluorouracil compared to treatment with mistletoe lectin. Onkologe 10:978–985

Bussing A, Raak C, Ostermann T (2012) Quality of life and related dimensions in cancer patients treated with mistletoe extract (Iscador): a meta-analysis. Evide Based Complem Altern Med 2012:219402

Cazacu M, Oniu T, Lungoci C, Mihailov A, Cipak A, Klinger R, Weiss T, Zarkovic N (2003) The influence of isorel on the advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 18:27–34

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J et al (1993) The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11:570–579

Cho JS, Na KJ, Lee Y, Kim YD, Ahn HY, Park CR, Kim YC (2016) Chemical pleurodesis using mistletoe extraction (ABNOVAviscum( R) Injection) for malignant pleural effusion. Ann Thoracic Cardiovascular Surg off J Assoc Thoracic Cardiovascular Surg Asia 22:20–26

Cho SJ, Kim SW (2018) Chemical pleurodesis using viscum album extract in gorham disease complicated with chylothorax. Acute Critic Care 33:105–109

Coates A, Glasziou P, McNeil D (1990) On the receiving end–III. Measurement of quality of life during cancer chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 1:213–217

Ebel MD, Rudolph I, Keinki C, Hoppe A, Muecke R, Micke O, Muenstedt K, Huebner J (2015) Perception of cancer patients of their disease, self-efficacy and locus of control and usage of complementary and alternative medicine. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 141:1449–1455

Ebrahim MA, El-Hadaad HA, Alemam OA, Keshta SA (2010) Efficacy and safety of viscum fraxini-2 in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase II study. Chin Ger J Clin Oncol 9:452–458

Eisenbraun J, Scheer R, Kroz M, Schad F, Huber R (2011) Quality of life in breast cancer patients during chemotherapy and concurrent therapy with a mistletoe extract. Phytomedicine 18:151–157

El-Kolaly RM, Abo-Elnasr M, El-Guindy D (2016) Outcome of pleurodesis using different agents in management of malignant pleural effusion. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberculosis 65:435–440

Elsasser-Beile U, Leiber C, Wolf P, Lucht M, Mengs U, Wetterauer U (2005a) Adjuvant intravesical treatment of superficial bladder cancer with a standardized mistletoe extract. J Urol 174:76–79

Elsasser-Beile U, Leiber C, Wetterauer U, Buhler P, Wolf P, Lucht M, Mengs U (2005b) Adjuvant intravesical treatment with a standardized mistletoe extract to prevent recurrence of superficial urinary bladder cancer. Anticancer Res 25:4733–4736

Enesel MB, Acalovschi I, Grosu V, Sbarcea A, Rusu C, Dobre A, Weiss T, Zarkovic N (2005) Perioperative application of the Viscum album extract Isorel in digestive tract cancer patients. Anticancer Res 25:4583–4590

Eom JS, Kim TH, Lee G, Ahn HY, Mok JH, Lee MK (2017) Chemical pleurodesis using mistletoe extracts via spray catheter during medical thoracoscopy for management of malignant pleural effusion. Respirol Case Rep 5:e00227

Eom JS, Ahn HY, Mok JH, Lee G, Jo E-J, Kim M-H, Lee K, Kim KU, Park H-K, Lee MK (2018) Pleurodesis using mistletoe extract delivered via a spray catheter during semirigid pleuroscopy for managing symptomatic malignant pleural effusion. Respiration 95:177–181

Felenda JE, Turek C, Stintzing FC (2019) Antiproliferative potential from aqueous Viscum album L. preparations and their main constituents in comparison with ricin and purothionin on human cancer cells. J Ethnopharmacol 236:100–107

Fellmer K (1968) A clinical trial of iscador. British Homeopat J 57:43–47

Freuding M, Keinki C, Micke O, Buentzel J, Huebner J (2019a) Mistletoe in oncological treatment: a systematic review: Part 1: survival and safety. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 145:695–707

Freuding M, Keinki C, Kutschan S, Micke O, Buentzel J, Huebner J (2019b) Mistletoe in oncological treatment: a systematic review: Part 2: quality of life and toxicity of cancer treatment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 145:927–939

Friedel WE, Matthes H, Bock PR, Zänker KS (2009) Systematic evaluation of the clinical effects of supportive mistletoe treatment within chemo- and/or radiotherapy protocols and long-term mistletoe application in nonmetastatic colorectal carcinoma: multicenter, controlled, observational cohort study. J Soc Integr Oncol 7:137–145

Friess H, Beger HG, Kunz J, Funk N, Schilling M, Buchler MW (1996) Treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer with mistletoe: results of a pilot trial. Anticancer Res 16:915–920

Gaafar R, Abdel Rahman ARM, Aboulkasem F, El Bastawisy AE (2014) Mistletoe preparation (Viscum Fraxini-2) as palliative treatment for malignant pleural effusion: a feasibility study with comparison to bleomycin. Ecancermedicalscience 8:424

Gardin NE (2009) Immunological response to mistletoe (Viscum album L.) in cancer patients: a four-case series. Phytother Res 23:407–411

Goebell PJ, Otto T, Suhr J, Rubben H (2002) Evaluation of an unconventional treatment modality with mistletoe lectin to prevent recurrence of superficial bladder cancer: a randomized phase II trial. J Urol 168:72–75

Gorter RW, van Wely M, Stoss M, Wollina U (1998) Subcutaneous infiltrates induced by injection of mistletoe extracts (Iscador). Am J Ther 5:181–187

Grossarth-Maticek R, Eysenck HJ, Boyle GJ (1995) Method of test administration as a factor in test validity: the use of a personality questionnaire in the prediction of cancer and coronary heart disease. Behav Res Ther 33:705–710

Grossarth-Maticek R, Kiene H, Baumgartner SM, Ziegler R, Grossarth-Maticek R, Kiene H, Baumgartner SM, Ziegler R (2001) Use of Iscador, an extract of European mistletoe (Viscum album), in cancer treatment: prospective nonrandomized and randomized matched-pair studies nested within a cohort study. Altern Ther Health Med 7:57–72

Grossarth-Maticek R, Ziegler R (2006a) Prospective controlled cohort studies on long-term therapy of breast cancer patients with a mistletoe preparation (Iscador). Forschende Komplementarmedizin 2006(13):285–292

Grossarth-Maticek R, Ziegler R (2006b) Randomised and non-randomised prospective controlled cohort studies in matched-pair design for the long-term therapy of breast cancer patients with mistletoe preparation (Iscador): a re-analysis. Eur J Med Res 11:485–495

Grossarth-Maticek R, Ziegler R (2007a) Efficacy and safety of the long-term treatment of melanoma with a mistletoe preparation (Iscador). Schweizerische Zeitschrift Fur Ganzheitsmedizin 19:325–332

Grossarth-Maticek RZR (2007) Prospective controlled cohort studies on long-term therapy of cervical cancer patients with a mistletoe preparation (Iscador). Forschende Komplement 14:140–147

Grossarth-Maticek R, Ziegler R (2007b) Prospective controlled cohort studies on long-term therapy of ovarian cancer patients with mistletoe (Viscum album L.) extracts Iscador. Arzneimittel-Forschung/drug Research 57:665–678

Grossarth-Maticek R, Ziegler R (2008) Randomized and non-randomized prospective controlled cohort studies in matched pair design for the long-term therapy of corpus uteri cancer patients with a mistletoe preparation (Iscador). Eur J Med Res 13:107–120

Günczler M, Osika C, Salzer G (1968) Results of surgery and postoperative care in gastric carcinoma. Wien Klin Wochenschr 80:105–106

Günczler M, Salzer G (1969) Iscadortherapie in der Nachbehandlung operierter Carcinome. Österreichische Ärztezeitung 24:2290–2298

Gutsch J, Werthmann PG, Rosenwald A, Kienle GS (2018) Complete remission and long-term survival of a patient with a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma under viscum album extracts after resistance to R-CHOP: a case report. Anticancer Res 38:5363–5369

Hajtó T, Hostanska K, Berki T, Pálinkás L, Boldizsár F, Németh P (2005) Oncopharmacological perspectives of a plant lectin (Viscum album Agglutinin-I): overview of recent results from in vitro experiments and in vivo animal models, and their possible relevance for clinical applications. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2:59–67

Heiny BM, Beuth J (1994) Mistletoe extract standardized for the galactoside-specific lectin (ML-1) induces beta-endorphin release and immunopotentiation in breast cancer patients. Anticancer Res 14:1339–1342

Holandino C, Melo MNDO, Oliveira AP, Batista JVDC, Capella MAM, Garrett R, Grazi M, Ramm H, Torre CD, Schaller G, Urech K, Weissenstein U, Baumgartner S (2020) Phytochemical analysis and in vitro anti-proliferative activity of Viscum album ethanolic extracts. BMC Complement Med Therap. 20:1–11

Horneber M, Bueschel G, Huber R, Linde K, Rostock M (2008) Mistletoe therapy in oncology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002833.pub2

Hostanska K, Hajto T, Spagnoli GC, Fischer J, Lentzen H, Herrman R (1995) A plant lectin derived from Viscum album induces cytokine gene expression and protein production in cultures of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Nat Immun 14:295–304

Huber R, Klein R, Berg PA, Ludtke R, Werner M (2002) Effects of a lectin- and a viscotoxin-rich mistletoe preparation on clinical and hematologic parameters: a placebo-controlled evaluation in healthy subjects. J Altern Complement Med 8:857–866

Huber R, Classen K, Werner M, Klein R (2006) In vitro immunoreactivity towards lectin-rich or viscotoxin-rich mistletoe (Viscum album L.) extracts iscador applied to healthy individuals: a randomised double-blind placebo controlled study. Arzneimittel Forschung Drug Res 56:447–456

Huber R, Ludtke H, Wieber J, Beckmann C (2011) Safety and effects of two mistletoe preparations on production of Interleukin-6 and other immune parameters—a placebo controlled clinical trial in healthy subjects. BMC Complement Altern Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-11-116

Huber R, Schlodder D, Effertz C, Rieger S, Tröger W (2017) Safety of intravenously applied mistletoe extract—results from a phase I dose escalation study in patients with advanced cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med 17:1–8

Huebner J, Micke O, Muecke R, Buentzel J, Prott FJ, Kleeberg U, Senf B, Muenstedt K (2014) User rate of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) of patients visiting a counseling facility for CAM of a German comprehensive cancer center. Anticancer Res 34:943–948

Hulsen H, Kron R, Mechelke F (1989) Influence of Viscum album preparations on the natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity of peripheral blood. Naturwissenschaften 76:530–531

Hwang WY, Kang MH, Lee SK, Yeom JS, Jung MH (2019) Prolonged stabilization of platinum-refractory ovarian cancer in a single patient undergoing long-term Mistletoe extract treatment: case report. Medicine 98:e14536–e14536

Jurin M, Zarkovic N, Hrzenjak M, Ilic Z (1993) Antitumorous and immunomodulatory effects of the Viscum album L. preparation Isorel. Oncology 50:393–398

Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH (1949) The clinical evaluation of chemo- therapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod CM (ed) Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. Columbia Univ Press, New York, pp 191–205

Kienle GS, Kiene H (2007) Complementary cancer therapy: a systematic review of prospective clinical trials on anthroposophic mistletoe extracts. Eur J Med Res 12:103–119

Kienle GS, Glockmann A, Schink M, Kiene H (2009) Viscum album L. extracts in breast and gynaecological cancers: a systematic review of clinical and preclinical research. J Experiment Clin Cancer Res. 28:79

Kienle GS, Kiene H (2010) Review article: Influence of Viscum album L (European mistletoe) extracts on quality of life in cancer patients: a systematic review of controlled clinical studies. Integr Cancer Ther 9:142–157

Kim KC, Yook JH, Eisenbraun J, Kim BS, Huber R (2012) Quality of life, immunomodulation and safety of adjuvant mistletoe treatment in patients with gastric carcinoma - a randomized, controlled pilot study. BMC Complement Altern Med 12:172

Kjaer M (1989) Mistletoe (Iscador) therapy in stage IV renal adenocarcinoma. a phase II study in patients with measurable lung metastases. Acta Oncol 28:489–494

Kleeberg UR, Suciu S, Brocker EB, Ruiter DJ, Chartier C, Lienard D, Marsden J, Schadendorf D, Eggermont AMM (2004) Final results of the EORTC 18871/DKG 80–1 randomised phase III trial. rIFN-alpha2b versus rIFN-gamma versus ISCADOR M versus observation after surgery in melanoma patients with either high-risk primary (thickness >3 mm) or regional lymph node metastasis. Europ J Cancer (oxford England 1990). 40:390–402

Klingbeil MFG, Xavier FCA, Sardinha LR, Severino P, Mathor MB, Rodrigues RV, Pinto DS Jr (2013) Cytotoxic effects of mistletoe (Viscum album L.) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Oncol Rep 30:2316–2322

Klose C, Jensen K, Herzig M, Mansmann U (2003) Multicentric, randomized, open, prospective clinical trial for the investigation of efficacy and tolerance and adverse drug reactions of HELIXOR® A in comparison to Lentinan in patients with non small cell lung cancer, breast cancer or ovarian cancer. Forschungsbericht Der Abteilung Medizinische Biometrie 45:1–121

Kröz M, Büssing A, von Laue HB, Reif M, Feder G, Schad F, Girke M, Matthes H (2009) Reliability and validity of a new scale on internal coherence (ICS) of cancer patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 7:59

Kümmell HC, S. M. (1996) Entwicklung eines Fragebogens zur Lebensqualität auf der Grundlage des anthroposophischen Menschenbildes: Herdecker Fragebogen zur Lebensqualität (HLQ). Der Merkurstab 49:109–122

Lange-Lindberg A-M, Velasco Garrido M, Busse R (2006) Mistletoe treatments for minimising side effects of anticancer chemotherapy. GMS Health Technol Assess 2:1–8

Lee Y-G, Jung I, Koo D-H, Kang D-Y, Oh TY, Oh S, Lee S-S (2019) Efficacy and safety of Viscum album extract (Helixor-M) to treat malignant pleural effusion in patients with lung cancer. Support Care Cancer 27:1945–1949

Leiberich P, Averbeck M, Grote-Kusch M, Schroeder A, Olbrich E, Kalden JR (1993) The quality of life of tumor patients as a multidimensional concept. Z Psychosom Med Psychoanal 39:26–37

Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): Komplementärmedizin in der Behandlung von onkologischen PatientInnen, Langversion 1.1, 2021, AWMF Registernummer: 032/055OL, https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/Leitlinien/Komplementär/Version_1/LL_Komplementär_Langversion_1.1.pdf

Lenartz D, Schierholz JM, Menzel J, Beuth J (1999) Influence of complementary mistletoe lectin therapy in the treatment of malignant glioma. Zeitschrift Fur Onkologie 31:44–46

Lenartz D, Dott U, Menzel J, Schierholz JM, Beuth J (2000) Survival of glioma patients after complementary treatment with galactoside-specific lectin from mistletoe. Anticancer Res 20:2073–2076

Lenartz D, Dott U, Menzel J, Schierholz JM, Beuth J (2001) Survival time of glioma patients after complementary treatment with galactoside-specific mistletoe lectin 1. Deutsche Zeitschrift Fur Onkologie 33:1–5

Leroi R (1977) Aftertreatment with viscum album following operation for mammary carcinoma. Helv Chir Acta 44:403–414

Loef M, Walach H (2020) Quality of life in cancer patients treated with mistletoe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Med Ther 20:227

Loewe-Mesch A, Kuehn JJ, Borho K, Abel U, Bauer C, Gerhard I, Schneeweiss A, Sohn C, Strowitzki T, Hagens CV (2008) Adjuvant simultaneous mistletoe chemotherapy in breast cancer-influence on immunological parameters, quality of life and tolerability. Forschende Komplementarmedizin. 15:22–30

Longhi A, Mariani E, Kuehn JJ (2009) A randomized study with adjuvant mistletoe versus oral Etoposide on post relapse disease-free survival in osteosarcoma patients. Europ J Integrat Med 1:31–39

Longhi A, Reif M, Mariani E, Ferrari S (2014) A Randomized study on postrelapse disease-free survival with adjuvant mistletoe versus oral etoposide in osteosarcoma patients. Evidence Based Complement Altern Med (eCAM) 2014:1–9

Longhi A, Cesari M, Serra M, Mariani E (2020) Long-term follow-up of a randomized study of oral etoposide versus viscum album fermentatum pini as maintenance therapy in osteosarcoma patients in complete surgical remission after second relapse. Sarcoma 2020:1–9

Mabed M, El-Helw L, Shamaa S (2004) Phase II study of viscum fraxini-2 in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer 90:65–69

Majewski A, Bentele W (1963) Supplementary treatment in carcinoma of the female genitals. Zbl Gynak 85:696–700

Matthes H, Friedel WE, Bock PR, Zänker KS (2010) Molecular mistletoe therapy: friend or foe in established anti-tumor protocols? A multicenter, controlled, retrospective pharmaco-epidemiological study in pancreas cancer. Curr Mol Med 10:430–439

Matthes H, Thronicke A, Hofheinz R-D, Baars E, Martin D, Huber R, Breitkreuz T, Bar-Sela G, Galun D, Schad F (2020) Statement to an insufficient systematic review on viscum album L. Therapy. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med (eCAM) 2020:1–9

Melzer J, Iten F, Hostanska K, Saller R (2009) Efficacy and safety of mistletoe preparations (viscum album) for patients with cancer diseases. Forschende Komplementarmedizin 16:217–226

Menke K, Schwermer M, Schramm A, Zuzak TJ (2019) Preclinical evaluation of antitumoral and cytotoxic properties of viscum album fraxini extract on pediatric tumor cells. Planta Med 85:1150–1159

Menke, K., M. Schwermer, J. Eisenbraun, A. Schramm & T. J. Zuzak (2020) Anticancer Effects of Viscum album Fraxini Extract on Medulloblastoma Cells in vitro. Complementary Medicine Research.

Nazaruk J, Orlikowski P (2016) Phytochemical profile and therapeutic potential of Viscum album L. Nat Prod Res 30:373–385

Oei SL, Thronicke A, Kroz M, Herbstreit C, Schad F (2018) The internal coherence of breast cancer patients is associated with the decision-making for chemotherapy and viscum album L. Treatment. Evidence Based Complement Altern Med 2018:1065271

Oei SL, Thronicke A, Kroz M, Herbstreit C, Schad F (2019a) Supportive effect of Viscum album L. extracts on the sense of coherence in non-metastasized breast cancer patients. Europ J Integrat Med 27:97–104

Oei SL, Thronicke A, Kroz M, Matthes H, Schad F (2019b) Use and safety of viscum album l applications in cancer patients with preexisting autoimmune diseases: findings from the network oncology study. Integr Cancer Ther 18:1534735419832367

Oh SJ (2020) Reducing malignant ascites and long-term survival in a patient with recurrent gastric cancer treated with a combination of docetaxel and mistletoe extract. Case Rep Oncol 13:528–533

Ostermann T, Raak C, Büssing A (2009) Survival of cancer patients treated with mistletoe extract (Iscador): a systematic literature review. BMC Cancer 9:451–451

Ostermann T, Appelbaum S, Poier D, Boehm K, Raak C, Büssing A (2020) A Systematic review and meta-analysis on the survival of cancer patients treated with a fermented viscum album L. extract (Iscador): an update of findings. Complement Med Res 27:260–271

Pelzer F, Tröger W, D. r. nat, (2018) Complementary treatment with mistletoe extracts during chemotherapy: safety, neutropenia, fever, and quality of life assessed in a randomized study. J Altern Complement Med 24:954–961

Pelzer F, Loef M, Martin DD, Baumgartner S (2022) Cancer-related fatigue in patients treated with mistletoe extracts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 30:6405–6418

Piao BK, Wang YX, Xie GR, Mansmann U, Matthes H, Beuth J, Lin HS (2004) Impact of complementary mistletoe extract treatment on quality of life in breast, ovarian and non-small cell lung cancer patients. A prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Anticancer Res 24:303–309

Reynel M, Villegas Y, Kiene H, Werthmann PG, Kienle GS (2018) Intralesional and subcutaneous application of Viscum album L. (European mistletoe) extract in cervical carcinoma in situ: a care compliant case report. Medicine 97:1–6

Reynel M, Villegas Y, Kiene H, Werthmann PG, Kienle GS (2019) Bilateral asynchronous renal cell carcinoma with lung metastases: a case report of a patient treated solely with high-dose intravenous and subcutaneous viscum album extract for a second renal lesion. Anticancer Res 39:5597–5604

Reynel M, Villegas Y, Werthmann PG, Kiene H, Kienle GS (2020) Long-term survival of a patient with an inoperable thymic neuroendocrine tumor stage IIIa under sole treatment with Viscum album extract: A CARE compliant clinical case report. Medicine 99:1–6

Ried M, Hofmann HS (2013) The treatment of pleural carcinosis with malignant pleural effusion. Dtsch Arztebl Int 110:313–318

Rose A, El-Leithy T, vom Dorp F, Zakaria A, Eisenhardt A, Tschirdewahn S, Rubben H (2015) Mistletoe plant extract in patients with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: results of a phase ib/iia single group dose escalation study. J Urol 194:939–943

Schad F, Atxner J, Buchwald D, Happe A, Popp S, Kroz M, Matthes H (2014) Intratumoral mistletoe (Viscum album L) therapy in patients with unresectable pancreas carcinoma: a retrospective analysis. Integr Cancer Ther 13:332–340

Schad F, Thronicke A, Merkle A, Matthes H, Steele ML (2017) Immune-related and adverse drug reactions to low versus high initial doses of Viscum album L. in cancer patients. Phytomedicine 36:54–58

Schad F, Axtner J, Kröz M, Matthes H, Steele ML (2018a) Safety of combined treatment with monoclonal antibodies and viscum album L preparations. Integr Cancer Ther 17:41–51

Schad F, Thronicke A, Steele ML, Merkle A, Matthes B, Grah C, Matthes H (2018b) Overall survival of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with Viscum album L In addition to chemotherapy, a real-world observational multicenter analysis. PLoS ONE 13:e0203058

Schierholz JM, Piao BK, Wang YX, Xie GR, Mansmann U, Matthes H, Beuth J, Lin HS (2003) Complementary cancer therapy with standardized mistletoe extracts. Results of a controlled prospective multicentric randomized clinical trial. Deutsche Zeitschrift Fur Onkologie 35:186–194

Schink M, Troger W, Dabidian A, Goyert A, Scheuerecker H, Meyer J, Fischer IU, Glaser F (2007) Mistletoe extract reduces the surgical suppression of natural killer cell activity in cancer patients. A randomized phase III trial. Forschende Komplementarmedizin 14:9–17

Schipper H, Clinch J, McMurray A, Levitt M (1984) Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: the functional living index-cancer: development and validation. J Clin Oncol 2:472–483

Schläppi M, Ewald C, Kuehn JJ, Weinert T, Huber R (2017) Fever therapy with intravenously applied mistletoe extracts for cancer patients: a retrospective study. Integr Cancer Ther 16:479–484

Schumacher K, Schneider B, Reich G, Stiefel T, Stoll G, Bock PR, Hanisch J, Beuth J (2002) Postoperative complementary therapy of primary breast cancer with lectin standardized mistletoe extract—an epidemiological, controlled, multicenter retrolective cohort study. Deutsche Zeitschrift Fur Onkologie 34:106–114

Schumacher K, Schneider B, Reich G, Stiefel T, Stoll G, Bock PR, Hanisch J, Beuth J (2003) Influence of postoperative complementary treatment with lectin-standardized mistletoe extract on breast cancer patients. A controlled epidemiological multicentric retrolective cohort study. Anticancer Res 23:5081–5087

Seifert G, Laengler A, Tautz C, Seeger K, Henze G (2007) Response to subcutaneous therapy with mistletoe in recurrent multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 48:591–592

Seifert G, Jesse P, Laengler A, Reindl T, Lüth M, Lobitz S, Henze G, Prokop A, Lode HN (2008) Molecular mechanisms of mistletoe plant extract-induced apoptosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Lett 264:218–228

Semiglasov VF, Stepula VV, Dudov A, Lehmacher W, Mengs U (2004) The standardised mistletoe extract PS76A2 improves QoL in patients with breast cancer receiving adjuvant CMF chemotherapy: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicentre clinical trial. Anticancer Res 24:1293–1302

Semiglazov VF, Stepula VV, Dudov A, Schnitker J, Mengs U (2006) Quality of life is improved in breast cancer patients by Standardised Mistletoe Extract PS76A2 during chemotherapy and follow-up: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicentre clinical trial. Anticancer Res 26:1519–1529

Shaw HS, Hobbs KB, Kroll DJ, Seewaldt VL (2004) Delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction with iscador M given in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 22:4432–4434

Son GS, Ryu WS, Kim HY, Woo SU, Park KH, Bae JW (2010) Immunologic response to mistletoe extract (Viscum album L.) after conventional treatment in patients with operable breast cancer. J Breast Cancer 13:14–18

Spitzer WO, Dobson AJ, Hall J, Chesterman E, Levi J, Shepherd R, Battista RN, Catchlove BR (1981) Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL-index for use by physicians. J Chronic Dis 34:585–597

Steele ML, Axtner J, Happe A, Kroz M, Matthes H, Schad F (2014a) Adverse drug reactions and expected effects to therapy with subcutaneous mistletoe extracts (Viscum album L) in cancer patients. Evidence Based Complement Altern Med. 2014:724258

Steele ML, Axtner J, Happe A, Kroz M, Matthes H, Schad F (2014b) Safety of intravenous application of mistletoe (Viscum album L.) preparations in oncology: an observational study. Evidence Based Complement Altern Med. 2014:236310

Steele ML, Axtner J, Happe A, Kroz M, Matthes H, Schad F (2015) Use and safety of intratumoral application of European mistletoe (Viscum album L.) preparations in oncology. Integr Cancer Ther 14:140–148

Steuer-Vogt MK, Bonkowsky V, Ambrosch P, Scholz M, Nei A, Strutz J, Hennig M, Lenarz T, Arnold W (2001) The effect of an adjuvant mistletoe treatment programme in resected head and neck cancer patients: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Eur J Cancer 37:23–31

Steuer-Vogt MK, Bonkowsky V, Scholz M, Fauser C, Licht K, Ambrosch P (2006) Influence of ML-1 standardized mistletoe extract on the quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. HNO 54:277–286

Stumpf C, Rosenberger A, Rieger S, Troger W, Schietzel M (2000) Mistletoe extracts in the therapy of malignant, hematological and lymphatic diseases–a monocentric, retrospective analysis over 16 years. Therapie Mit Mistelextrakten Bei Malignen Hamatologischen Und Lymphatischen Erkrankungeneine Monozentrische Retrospektive Analy Uber 16 Jahre. 7:139–146

Stumpf C, Rosenberger A, Rieger S, Troger W, Schietzel M, Stein GM (2003) Retrospective study of malignant melanoma patients treated with mistletoe extracts. Retrospektive Untersuchung Von Patienten Mit Malignem Melanom Unter Einer Misteltherapie 10:248–255

Tabiasco J, Pont F, Fournie J-J, Vercellone A (2002) Mistletoe viscotoxins increase natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Eur J Biochem 269:2591–2600

Thronicke A, Steele ML, Grah C, Matthes B, Schad F (2017) Clinical safety of combined therapy of immune checkpoint inhibitors and Viscum album L. therapy in patients with advanced or metastatic cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med 17:1–10

Thronicke A, Oei SL, Merkle A, Matthes H, Schad F (2018) Clinical safety of combined targeted and viscum album L. Therapy in Oncological Patients. Medicines, Basel, Switzerland, p 5

Thronicke A, Reinhold T, von Trott P, Matthes H, Schad F (2020a) Cost-effectiveness of real-world administration of concomitant viscum album L. therapy for the treatment of stage IV pancreatic cancer. Evidence Based Complement Altern Med (eCAM). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3543568

Thronicke A, Matthes B, von Trott P, Schad F, Grah C (2020b) Overall survival of nonmetastasized NSCLC patients treated with add-on viscum album L: a multicenter real-world study. Integrat Cancer Therap. 19:153735420940384

Tröger W, Jezdic S, Zdrale Z, Tisma N, Hamre HJ, Matijasevic M (2009) Quality of life and neutropenia in patients with early stage breast cancer: a randomized pilot study comparing additional treatment with mistletoe extract to chemotherapy alone. Breast Cancer Basic Clin Res. 3:35–45

Tröger W (2011) Connection between quality of life and neutropenia in breast cancer patients who were solely treated with chemotherapy or additionally with mistletoe therapy: results of a randomized study. [German] (Zusammenhang von Lebensqualitt und Neutropenie bei Brustkrebspatientinnen, die alleine mit Chemotherapie oder zustzlich mit Misteltherapie behandelt wurden: ergebnisse einer randomisierten Studie.). Deutsche Zeitschrift Fur Onkologie 43:58–67

Tröger W, Zdrale Z, Stankovic N, Matijasevic M (2012) Five-year follow-up of patients with early stage breast cancer after a randomized study comparing additional treatment with Viscum album (L.) extract to chemotherapy alone. Breast Cancer Basic Clin Res 6:173–180

Tröger W, Galun D, Reif M, Schumann A, Stanković N, Milićević M (2013) Viscum album [L.] extract therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a randomised clinical trial on overall survival. Eur J Cancer 49:3788–3797

Tröger W, Galun D, Reif M, Schumann A, Stanković N, Milićević M (2014a) Quality of life of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer during treatment with mistletoe: a randomized controlled trial. Deutsches Arzteblatt Intern. 111:493–502

Tröger W, Ždrale Z, Tišma N, Matijašević M (2014b) Additional therapy with a mistletoe product during adjuvant chemotherapy of breast cancer patients improves quality of life: an open randomized clinical pilot trial. Evidence Based Complement Altern Med (eCAM). 2014:1–9

Tröger W, Zdrale Z, Stankovic N (2016) 5 Year follow-up of patients with early stage breast cancer after a randomized study with viscum album (L.) extract. Deutsche Zeitschrift Fur Onkologie 48:105–110

von Zerssen D (1976) Klinische Selbstbeurteilungs-Skalen (KSb-S) aus dem Münchener Psychiatrischen Informations-System (PSYCHIS München). Die Befindlichkeits-Skala: Parallelformen Bf-S und Bf-S’. Beltz, Weinheim

Werthmann PG, Helling D, Heusser P, Kienle GS (2014) Tumour response following high-dose intratumoural application of Viscum album on a patient with adenoid cystic carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep 2014:1–5

Werthmann PG, Hintze A, Kienle GS (2017a) Complete remission and long-term survival of a patient with melanoma metastases treated with high-dose fever-inducing Viscum album extract: a case report. Med (united States) 96:8731

Werthmann PG, Saltzwedel G, Kienle GS (2017b) Minor regression and long-time survival (56 months) in a patient with malignant pleural mesothelioma under Viscum album and Helleborus niger extracts–a case report. J Thorac Dis 9:E1064–E1070

Werthmann PG, Huber R, Kienle GS (2018a) Durable clinical remission of a skull metastasis under intralesional Viscum album extract therapy: case report. Head Neck 40:E77–E81

Werthmann PG, Inter P, Welsch T, Sturm A-K, Grutzmann R, Debus M, Sterner M-G, Kienle GS (2018b) Long-term tumor-free survival in a metastatic pancreatic carcinoma patient with FOLFIRINOX/Mitomycin, high-dose, fever inducing Viscum album extracts and subsequent R0 resection: a case report. Medicine 97:e13243

Werthmann PG, Kempenich R, Kienle GS (2018c) Long-term tumor-free survival in a patient with stage iv epithelial ovarian cancer undergoing high-dose chemotherapy and viscum album extract treatment: a case report. Permanente J 23:18–025

Werthmann PG, Kindermann L, Kienle GS (2018d) A 21-year course of Merkel cell carcinoma with adjuvant Viscum album extract treatment: a case report. Complement Ther Med 38:58–60

Werthmann PG, Kempenich R, Lang-Averous G, Kienle GS (2019a) Long-term survival of a patient with advanced pancreatic cancer under adjunct treatment with Viscum album extracts: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 25:1524–1530

Werthmann PG, Kindermann L, Kienle GS (2019b) Chemoimmunotherapy in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a case report of a long-term survivor adjunctly treated with viscum album extracts. Complement Med Res 26:276–279

Wode K, Schneider T, Lundberg I, Kienle GS (2009) Mistletoe treatment in cancer-related fatigue: a case report. Cases J 2:77–77

Zaenker KS, Matthes H, Bock PR, Hanisch J (2012) A specific mistletoe preparation (Iscador-Qu) in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients: more than just supportive care? Journal of Cancer Science and Therapy 4:264–270

Zhao S, Ke M, Huang T, Hong T, Yu H, Zhang X (2019) Viscum album extract suppresses cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in bladder cancer cells. Trop J Pharm Res 18:1711–1717

Zuzak TJ, Wasmuth A, Bernitzki S, Schwermer M, Längler A, Längler A (2018) Safety of high-dose intravenous mistletoe therapy in pediatric cancer patients: a case series. Complement Ther Med 40:198–202

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. There was no funding of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study selection and data extraction was done by H.S. and controlled by J.H. independently. In case of disagreement, consensus was made by discussion. H.S. and J.H wrote the main manuscript. J.B., C.K. and J.B. have revised the manuscript and noted changes. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Staupe, H., Buentzel, J., Keinki, C. et al. Systematic analysis of mistletoe prescriptions in clinical studies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 149, 5559–5571 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-04511-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-04511-2