Abstract

Inappropriate perioperative fluid load can lead to postoperative complications and death. This retrospective study was designed to investigate the association between intraoperative fluid load and outcomes in neonates undergoing non-cardiac surgery. From April 2020 to September 2022, 940 neonates who underwent non-cardiac surgery were retrospectively enrolled and their perioperative data were harvested for further analysis. According to recorded intraoperative fluid volumes defined as ml.kg−1 h−1, patients were mandatorily divided into quintile with fluid load as restrictive (quintile 1, Q1), moderately restrictive (Q2), moderate (Q3), moderately liberal (Q4), and liberal (Q5). The primary outcomes were defined as prolonged length of hospital stay (LOS) (postoperative LOS ≥ 14 days), complications beyond prolonged LOS, and 30-day mortality. Secondary outcomes included postoperative complications within 14 days of hospital stay. The intraoperative fluid load was in Q1 of 6.5 (5.3–7.3) (median and IQR); Q2: 9.2 (8.7–9.9); Q3: 12.2 (11.4–13.2); Q4: 16.5 (15.4–18.0); and Q5: 26.5 (22.3–32.2) ml.kg−1 h−1. The odd of prolonged LOS was positively correlated with an increase fluid volume (Q5 quintile: OR 2.602 [95% CI 1.444–4.690], P = 0.001), as well as complications beyond prolonged LOS (Q5: OR 3.322 [95% CI 1.656–6.275], P = 0.001). The overall 30-day mortality rate was increased with high intraoperative fluid load but did not reach to a statistical significance after adjusted with confounders. Furthermore, the highest quintile of fluid load (26.5 ml.kg−1 h−1, IQR [22.3–32.2]) (Q5 quintile) was significantly associated with longer postoperative mechanical ventilation time compared with Q1 (Q5: OR 2.212 [95% CI 1.101–4.445], P = 0.026).

Conclusion: Restrictive intraoperative fluid load had overall better outcomes, whilst high fluid load was significantly associated with prolonged LOS and complications after non-cardiac surgery in neonates.

Trial registration: Chictr.org.cn Identifier: ChiCTR2200066823 (December 19, 2022).

What is Known: • Inappropriate perioperative fluid load can lead to postoperative complications and even death. | |

What is New: • High perioperative fluid load was significantly associated with an increased length of stay after non-cardiac surgery in neonates, whilst low fluid load was consistently related to better postoperative outcomes. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Perioperative fluid management is recognized as a crucial factor affecting surgical outcomes [1, 2]. Proper administration of intravenous fluids is essential for maintaining normal physiological function in pediatric surgical patients. However, low blood volume during perioperative period can result in decreased cardiac output and reduced tissue perfusion, potentially leading to acute kidney injury. Conversely, high blood volume may be linked to an increased risk of adverse events, including tissue edema, acid-base disorders, heart failure, and even death [3, 4].

These postoperative complications increased postoperative mortality, prolonged length of hospital stay (LOS), and re-admitted to hospital [5], thereby negatively affected long-term survival [2, 6, 7]. The choice between restrictive and liberal fluid therapy is still debating. Currently, “goal-directed fluid therapy” (GDFT) is steadily gaining popularity for appropriate perioperative fluid management, as it has been shown to reduce perioperative complications and mortality [8,9,10]. A study by Osawa and colleagues demonstrated that perioperative GDFT reduced the incidence of low cardiac output syndrome in patients undergoing cardiac surgery [11]. However, GDFT has not yet been optimized for clinical use in neonates. Therefore, it is crucial to determine the optimal intravenous infusion volume to enhance perioperative fluid management in neonates, aiming to maximize therapeutic benefits while minimizing iatrogenic toxicity [12].

In the past decades, perioperative fluid management has been focused on adults and children but studies on neonates are limited [1, 8, 13]. In this study, we investigated a large cohort of neonates undergoing non-cardiac surgery and analyzed the impact of high or low intraoperative fluid load on postoperative clinical outcomes aiming to provide guidance on intraoperative fluid management for neonates.

Methods

Study design and setting

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee Board of Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2022-IRB-273, December 6, 2022), registered at chictr.org.cn. (ChiCTR2200066823, December 19, 2022) and conducted a retrospective analysis of surgical data from April 2020 to September 2022 in the same hospital as above. All neonates who underwent non-cardiac surgery and general anesthesia with intraoperative endotracheal intubation were included in the study (Fig. 1). Demographics, intraoperative, and outcome data were collected from clinical and administrative database. The excluded criteria were as follows: (1) non-tracheal intubation general anesthesia, (2) undergoing cardiac surgery, (3) a history of surgery, (4) severe congenital heart disease, (5) anesthesia time less than 30 min, and (6) data incompletion.

Exposure variable

The total fluid load was calculated based on the anesthesia record and defined as the sum effective volumes of crystalloid, colloid, and blood products administered between onset of anesthesia till surgery completion before arrived to the post anesthesia care unit (PACU) or intensive care unit (ICU) [1, 14]. Patients were categorized into five quintiles (Q) based on the fluid volume per kilogram of body weight per hour during intraoperative period: restrictive (quintile 1, Q1), moderately restrictive (quintile 2, Q2), moderate (quintile 3, Q3), moderately liberal (quintile 4, Q4), and liberal (quintile 5, Q5).

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes included a prolonged LOS (postoperative hospital stay equal and more than 14 days) [15, 16], complications beyond prolonged LOS, and 30-day mortality after surgery. The secondary outcomes were postoperative complications including (i) postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs), (ii) acute kidney injury (AKI), (iii) hepatic dysfunction, (iv) surgical site infection, (v) thrombus formation, and (vi) postoperative hypotension required vasopressors. The data of postoperative mechanical ventilation time equal and more than 24 h and postoperative blood transfusion were also collected.

Postoperative pulmonary complications were defined as the occurrence of respiratory infection, respiratory failure, pleural effusion, atelectasis, pneumothorax, bronchospasm, or aspiration pneumonitis [17]. AKI was defined as an increase by 0.3 mg/dL or by 50% relative to its before of serum creatinine compared to preoperative levels within 48 h after surgery, or the presence of an AKI diagnostic code within 7 days after surgery [18, 19]. Postoperative hypotension, in preterm neonates, was defined as a mean blood pressure below 30 mmHg [20, 21], whilst, for term neonates, it is lower than 39 mmHg or decreased by 20% relative to the baseline [22].

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) as all data are not normally distributed. They were analyzed with the Kruskal-Wallis test. Categorical data were reported as patients’ numbers and percentages (n, %) and compared with chi-square test or fisher’s exact test. Binomial logistic regressions were employed to assess the association between fluid volume quintiles and the binary outcomes. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to determine the associations between fluid quintiles and outcomes. The covariates included in the models were age, weight, premature, gender, ASA physical status, admission type, surgery type, anesthesia duration, intraoperative lactic acid, intraoperative blood loss, and intraoperative vasopressor drugs. Survival analysis was conducted using Kaplan-Meier curves for each intervention group, and the Log Rank test was used for comparison. A double-tailed P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM, USA) or GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, USA).

Results

Study cohort and patient characteristics

A total of 940 neonates met the study criteria in the period from April 2020 to September 2022 (Fig. 1). The cohort had a median age (IQR) of 6.0 (2.0–14.0) days and the bodyweight of 2.9 (2.3–3.4) kg. Among the cohort, 521 (55.4%) were males. The majority of patients had ASA status Ι and II (787, 83.7%). The most common surgery type was gastrointestinal (758, 80.6%), followed by neurosurgery (91, 9.7%), and thoracic (61, 6.5%). The median (IQR) surgery time and anesthesia time were 73.0 (44.0–102.0) and 127.0 (90.0–160.0) min, respectively (Table 1).

During surgery, the median (IQR) fluid load received was 12.2 (8.7–18.0) ml kg−1 h−1 (Table 1). The fluid load received in each of the five quintiles was as follows: Q1: lowest (n = 188): 6.5 (5.3–7.3) ml kg−1 h−1; Q2: low (n = 188): 9.2 (8.7–9.9); Q3: moderate (n = 188): 12.2 (11.4–13.2); Q4: high (n = 188): 16.5 (15.4–18.0); and Q5: highest (n = 188): 26.5 (22.3–32.2).

Primary outcome

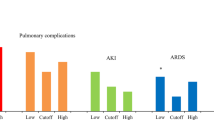

Of the total patients, 432 (46.0%) had a prolonged LOS. Adjusted outcomes revealed that increasing fluid volumes were significantly associated with prolonged LOS (Q5: OR 2.602 [95% CI 1.444–4.690], Q4: OR 2.754 [95% CI 1.622–4.676], Q3: OR 1.996 [95% CI 1.195–3.334], Q2: OR 1.872 [95% CI 1.112–3.151], all P < 0.05, p for trend = 0.001) (Fig. 2). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.701 (95% CI: 0.668–0.734) with a cutoff value of 13.15 ml kg−1 h−1 (Fig. 3a).

Effect of intraoperative fluid load on postoperative outcomes. The association between total intraoperative fluid load and postoperative outcomes was analyzed using multivariable logistic regression. The association between intraoperative fluid load and prolonged LOS, complications with prolonged LOS, PPCs, postoperative transfusion, postoperative mechanical ventilation time ≥ 24 h, and 30-day mortality were analyzed using multivariable models. The adjusted OR with 95% CI for all outcomes during the study period is shown (compared to Q1). CI: confidence intervals; OR: odds ratios; LOS: length of stay; PPCs: postoperative pulmonary complications

Similar results were found for complications beyond prolonged LOS (282, 30.0%). Increase liquid volumes were consistently associated with a higher risk of prolonged LOS (all P < 0.05, P for trend = 0.001) (Fig. 2). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.698 (95% CI: 0.662–0.735) with a cutoff value of 13.20 ml kg−1 h−1) (Fig. 3b).

Among the patients, 42 (4.5%) died within 30-days after surgery (Table 2). The 30-day mortality in different groups is shown in Fig. 4. There was a statistical difference in survival rates among the five groups (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). However, high intraoperative fluid load was not found to be associated with 30-day mortality after adjusted with confounders (Fig. 2).

Secondary outcomes

The complications in different categories were as follows: postoperative pulmonary complications: 378 (40.2%), AKI 15 (1.6%), hepatic dysfunction: 16 (1.7%), surgical site infection: 27 (2.9%), thrombus formation: 15 (1.6%), and postoperative hypotension required vasopressors: 70 (7.4%) (Table 2).

The median (IQR) postoperative mechanical ventilation time was 14.3 (7.7–26.6) hours (Table 2). Higher fluid load was also associated with a higher risk of mechanical ventilation time ≥ 24 h (Q5: OR 2.212, 95% CI 1.101–4.445, P = 0.026, P for trend = 0.020) (Fig. 2).

Higher intraoperative fluid administration was associated with increased PPCs (P < 0.001), hepatic dysfunction (P = 0.005), postoperative hypotension required vasopressors (P < 0.001), acidosis (P < 0.001), blood transfusion (P < 0.001), lactic acid (P < 0.001), decreased hemoglobin (P < 0.001), and hematocrit (P < 0.001) (Table 2). However, these postoperative outcomes did not show statistically significant association with fluid load after adjusted with risk factors (Fig. 2).

Discussion

In the current study, our data demonstrated that high fluid administration was associated with an increased risk of prolonged postoperative length of hospital stay and overall complication. Conversely, low fluid load (Q1) showed better postoperative outcomes. This study contributes to the existing literature by providing insights into the association between intraoperative fluid management and clinical outcomes in neonates.

Previous studies showed that a U-shaped relationship exists between perioperative fluid load and complications in non-cardiac surgery, indicating that both very high and very low fluid load can be harmful [1, 13, 23]. However, those studies were only conducted in adults, and there is a lack of research specifically focusing on neonates. It is important to consider that there may be differences in organ function between adults and neonates. In neonates, the effective renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is increased with gestational age. After birth, the GFR increases significantly and reaches to adult levels by 2 years of age [19]. Due to the low GFR and renal blood flow in infants, especially in preterm infants, they have limited capacity to cope large volumes of fluids and are vulnerable to high fluid overload. It has been reported that early fluid accumulation is associated with increased mortality in critically ill children in the ICU [24]. Furthermore, fluid balance is associated with mechanical ventilation on postnatal day 14 in the extremely premature neonates [25]. This may explain why our study findings suggest a correlation between lower fluid infusion and better prognosis in neonates.

Recent studies highlighted the importance of ICU length of stay as a key measure of postoperative recovery. It is considered to be a proxy for acute physical recovery and serves as a significant predictor of long-term recovery [6]. In our study, we aimed to compare the association between different fluid load and prolonged LOS/complications to assess their impact on patient outcomes. Our findings revealed a positive correlation between the amount of fluid administration and the increase of prolonged LOS. Specifically, in patients who received higher fluid load (Q5), both prolonged LOS and complications were significantly increased. These results are consistent with previous research findings [1] and are similar to what has been found in the patients undergoing colon and rectal surgery [13, 26]. It is important to note that complications resulting from fluid overload may take time to resolve, leading to longer ICU stays. On the other hand, the lower fluid load (Q1) showed shorter postoperative LOS, suggesting that this may be a relatively suitable fluid regimen for neonates. However, further multicenter study is needed to provide additional evidence in supporting our finding.

Previous studies in adult patients showed that both very high and very low fluid loads are associated with an increased risk of mortality [1, 23]. In our study, we had a large cohort of neonates with varying admission types (emergency or elective), and surgery types. This allowed us to reduce bias related to fluid quantities and types and to objectively evaluate the influence of intraoperative fluids on outcomes. However, we did not find a significant association between fluid load and 30-day mortality risk after adjusted with various related factors although the high fluid load (Q5) was associated with a low rate of survival. In children admitted to pediatric ICU, a previous study demonstrated that there was a 6% increase in odds of mortality for every 1% increase in percentage fluid overload [27]. Further research is needed to further our understanding to the underlying mechanisms for this discrepancy and to investigate other potential factors that may contribute to the relationship between fluid load and mortality in neonates.

Excessive fluid administration can have harmful effects on the lungs, leading to pulmonary edema, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and pneumonia. Pulmonary edema impairs gas exchange, increasing the risk of infection, respiratory failure, and the need for reintubation. Postoperative pulmonary complications are the most common surgical related complications and are known to significantly increase postoperative LOS, mortality, and healthcare costs. A meta-analysis of several trials demonstrated that higher intraoperative fluid load were associated with increased odds of postoperative pulmonary edema and pneumonia [28]. In our study, after adjusted with other factors, we did not find that the high intraoperative fluid load (Q5) was associated with a high risk of postoperative pulmonary complications. However, we did find a positive association between fluid load and the incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications and the duration of postoperative mechanical ventilation (≥ 24 h). This finding is consistent with a previous study showing that for every 10% increase in peak positive fluid balance, there is a 103% increase in the odds of requiring mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 14 [25]. Additionally, the positive fluid balance in the first postnatal week was linked to mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 7 in neonates born less than 36 weeks gestational age [29].

Previous studies reported that moderate fluid load has been shown to have the lowest risk of developing AKI [1, 23, 30]. Hypovolemia can lead to renal hypoperfusion, which can result in acute tubular necrosis and renal dysfunction [31]. On the other hand, hypervolemia reduced glomerular filtration and promoted renal parenchymal edema by increasing central venous pressure (CVP) [1]. This can affect renal uptake and lead to the accumulation of serum creatinine, ultimately leading to the occurrence of AKI [31]. In our study, we did not find a significant association between fluid load and AKI although AKI is common in critically ill neonates [4]. Further research with a larger sample size is needed to better understand the association between intraoperative fluid load and AKI in neonates.

This study has several limitations. First, the data were retrospectively collected from a single center, which may introduce regional limitations and potential biases. Secondly, our study only focused on short-term outcomes related to intraoperative fluid load, and the long-term outcomes are unknown. Thirdly, major surgery in general needs long surgery time and causes more traumatic injury to young patients. However, how much surgical related factors and surgical disease severity contributed to the findings of the current study is unknown. Future multicenter cohort studies are needed to determine the optimal fluid management strategies in neonates.

In conclusion, our study highlights the association between excessive fluid load and poor postoperative outcomes in neonates undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Neonates are sensitive and vulnerable, and even small treatment alterations can have a significant impact on outcomes. Therefore, identifying appropriate intraoperative fluid management strategies are crucial to minimize complications and promote faster postoperative recovery in this patient population.

Data availability

Available upon request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LOS:

-

Length of hospital stay

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- PPCs:

-

Postoperative pulmonary complications

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

References

Shin CH, Long DR, McLean D, Grabitz SD, Ladha K, Timm FP, Thevathasan T, Pieretti A, Ferrone C, Hoeft A, Scheeren TWL, Thompson BT, Kurth T, Eikermann M (2018) Effects of intraoperative fluid management on postoperative outcomes: a hospital registry study. Ann Surg 267:1084–1092

Miller TE, Myles PS (2019) Perioperative fluid therapy for major surgery. Anesthesiology 130:825–832

Neilson J, O’Neill F, Dawoud D, Crean P, Guideline Development G (2015) Intravenous fluids in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 351:h6388

Jetton JG, Boohaker LJ, Sethi SK, Wazir S, Rohatgi S, Soranno DE, Chishti AS, Woroniecki R, Mammen C, Swanson JR, Sridhar S, Wong CS, Kupferman JC, Griffin RL, Askenazi DJ, Neonatal Kidney C (2017) Incidence and outcomes of neonatal acute kidney injury (AWAKEN): a multicentre, multinational, observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 1:184–194

Lawson EH, Hall BL, Louie R, Ettner SL, Zingmond DS, Han L, Rapp M, Ko CY (2013) Association between occurrence of a postoperative complication and readmission: implications for quality improvement and cost savings. Ann Surg 258:10–18

Lucocq J, Scollay J, Patil P (2023) Defining prolonged length of stay (PLOS) following elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy and derivation of a preoperative risk score to inform resource utilization, risk stratification, and patient consent. Ann Surg 277:e1051–e1055

Goense L, Meziani J, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R (2019) Impact of postoperative complications on outcomes after oesophagectomy for cancer. Br J Surg 106:111–119

Heming N, Moine P, Coscas R, Annane D (2020) Perioperative fluid management for major elective surgery. Br J Surg 107:e56–e62

Messina A, Robba C, Calabro L, Zambelli D, Iannuzzi F, Molinari E, Scarano S, Battaglini D, Baggiani M, De Mattei G, Saderi L, Sotgiu G, Pelosi P, Cecconi M (2021) Association between perioperative fluid administration and postoperative outcomes: a 20-year systematic review and a meta-analysis of randomized goal-directed trials in major visceral/noncardiac surgery. Crit Care 25:43

Pesonen E, Vlasov H, Suojaranta R, Hiippala S, Schramko A, Wilkman E, Eranen T, Arvonen K, Mazanikov M, Salminen US, Meinberg M, Vahasilta T, Petaja L, Raivio P, Juvonen T, Pettila V (2022) Effect of 4% albumin solution vs ringer acetate on major adverse events in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 328:251–258

Osawa EA, Rhodes A, Landoni G, Galas FR, Fukushima JT, Park CH, Almeida JP et al (2016) Effect of perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic resuscitation therapy on outcomes following cardiac surgery: a randomized clinical trial and systematic review. Crit Care Med 44:724–733

Lilot M, Ehrenfeld JM, Lee C, Harrington B, Cannesson M, Rinehart J (2015) Variability in practice and factors predictive of total crystalloid administration during abdominal surgery: retrospective two-centre analysis. Br J Anaesth 114:767–776

Thacker JK, Mountford WK, Ernst FR, Krukas MR, Mythen MM (2016) Perioperative fluid utilization variability and association with outcomes: considerations for enhanced recovery efforts in sample US surgical populations. Ann Surg 263:502–510

Orbegozo Cortes D, Gamarano Barros T, Njimi H, Vincent JL (2015) Crystalloids versus colloids: exploring differences in fluid requirements by systematic review and meta-regression. Anesth Analg 120:389–402

Aga Z, Machina M, McCluskey SA (2016) Greater intravenous fluid volumes are associated with prolonged recovery after colorectal surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Anaesth 116:804–810

Pagowska-Klimek I, Pychynska-Pokorska M, Krajewski W, Moll JJ (2011) Predictors of long intensive care unit stay following cardiac surgery in children. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 40:179–184

Jammer I, Wickboldt N, Sander M, Smith A, Schultz MJ, Pelosi P, Leva B, Rhodes A, Hoeft A, Walder B, Chew MS, Pearse RM, European Society of A, European Society of Intensive Care M (2015) Standards for definitions and use of outcome measures for clinical effectiveness research in perioperative medicine: European Perioperative Clinical Outcome (EPCO) definitions: a statement from the ESA-ESICM joint taskforce on perioperative outcome measures. Eur J Anaesthesiol 32:88–105

KDIGO AKI Work Group (2012) KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2:1–138

Starr MC, Charlton JR, Guillet R, Reidy K, Tipple TE, Jetton JG, Kent AL, Abitbol CL, Ambalavanan N, Mhanna MJ, Askenazi DJ, Selewski DT, Harer MW, Neonatal Kidney Collaborative Board (2021) Advances in neonatal acute kidney injury. Pediatrics 148(5):e2021051220

Houck CS, Vinson AE (2017) Anaesthetic considerations for surgery in newborns. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 102:F359–F363

Joint Working Group of the British Association of Perinatal Medicine and the Research Unit of the Royal College of Physicians (1992) Development of audit measures and guidelines for good practice in the management of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Arch Dis Child 67:1221–1227

Szostek AS, Saunier C, Elsensohn MH, Boucher P, Merquiol F, Gerst A, Portefaix A, Chassard D, De Queiroz Siqueira M (2023) Effective dose of ephedrine for treatment of hypotension after induction of general anaesthesia in neonates and infants less than 6 months of age: a multicentre randomised, controlled, open label, dose escalation trial. Br J Anaesth 130:603–610

Miller TE, Mythen M, Shaw AD, Hwang S, Shenoy AV, Bershad M, Hunley C (2021) Association between perioperative fluid management and patient outcomes: a multicentre retrospective study. Br J Anaesth 126:720–729

Selewski DT, Gist KM, Basu RK, Goldstein SL, Zappitelli M, Soranno DE, Mammen C, Sutherland SM, Askenazi DJ, Ricci Z, Akcan-Arikan A, Gorga SM, Gillespie SE, Woroniecki R, Assessment of the Worldwide Acute Kidney Injury RA, Epidemiology I (2023) Impact of the magnitude and timing of fluid overload on outcomes in critically ill children: a report from the multicenter international assessment of worldwide acute kidney injury, renal angina, and epidemiology (AWARE) study. Crit Care Med 51:606–618

Starr MC, Griffin R, Gist KM, Segar JL, Raina R, Guillet R, Nesargi S, Menon S, Anderson N, Askenazi DJ, Selewski DT, Neonatal Kidney Collaborative Research C (2022) Association of fluid balance with short- and long-term respiratory outcomes in extremely premature neonates: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 5:e2248826

Abd El Aziz MA, Grass F, Calini G, Lovely JK, Jacob AK, Behm KT, D’Angelo AD, Shawki SF, Mathis KL, Larson DW (2022) Intraoperative fluid management a modifiable risk factor for surgical quality - improving standardized practice. Ann Surg 275:891–896

Alobaidi R, Morgan C, Basu RK, Stenson E, Featherstone R, Majumdar SR, Bagshaw SM (2018) Association between fluid balance and outcomes in critically Ill children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 172:257–268

Corcoran T, Rhodes JE, Clarke S, Myles PS, Ho KM (2012) Perioperative fluid management strategies in major surgery: a stratified meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 114:640–651

Arikan AA, Zappitelli M, Goldstein SL, Naipaul A, Jefferson LS, Loftis LL (2012) Fluid overload is associated with impaired oxygenation and morbidity in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 13:253–258

Myles PS, Bellomo R, Corcoran T, Forbes A, Peyton P, Story D, Christophi C, Leslie K, McGuinness S, Parke R, Serpell J, Chan MTV, Painter T, McCluskey S, Minto G, Wallace S, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists Clinical Trials Network and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group (2018) Restrictive versus liberal fluid therapy for major abdominal surgery. N Engl J Med 378:2263–2274

Ronco C, Bellomo R, Kellum JA (2019) Acute kidney injury. Lancet 394:1949–1964

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 82372159, 81971809, 82230074, and 82072221).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: YJ, XF, and DM; data analysis: MQ, JZ, and KZ; data acquisition: JZ, WZ, CJ, BC, and ZL; writing of original draft: MQ; revising the article: KZ, YH, and JH; revising and final approval of the version to be submitted: YJ, XF, and DM. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee Board of Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2022-IRB-273, December 6, 2022), registered at chictr.org.cn (ChiCTR2200066823) on December 19, 2022.

Consent to participate

This is an observational study. The local research ethics committee has confirmed that informed consent is not required.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Daniele De Luca

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qian, M., Zhao, J., Zhang, K. et al. High intraoperative fluid load associated with prolonged length of hospital stay and complications after non-cardiac surgery in neonates. Eur J Pediatr (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-024-05628-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-024-05628-x