Abstract

To determine the early factors associated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) failure in moderate-to-late preterm infants (32 + 0/7 to 36 + 6/7 weeks’ gestation) from the NEOBS cohort study. The NEOBS study was a multi-center, prospective, observational study in 46 neonatal intensive care units in France, which included preterm and late preterm infants with early neonatal respiratory distress. This analysis included a subset of the NEOBS population who had respiratory distress and required ventilatory support with CPAP within the first 24 h of life. CPAP failure was defined as the need for tracheal intubation within 72 h of CPAP initiation. Maternal and neonatal clinical parameters in the delivery room and clinical data at 3 h of life were analyzed. CPAP failure occurred in 45/375 infants (12%), and compared with infants with CPAP success, they were mostly singletons (82.2% vs. 62.1%; p < 0.01), had a lower Apgar score at 10 min of life (9.1 ± 1.3 vs. 9.6 ± 0.8; p = 0.02), and required a higher fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2; 34.4 ± 15.9% vs. 22.8 ± 4.1%; p < 0.0001) and a higher FiO2*positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) (1.8 ± 0.9 vs. 1.1 ± 0.3; p < 0.0001) at 3 h. FiO2 value of 0.23 (R2 = 0.73) and FiO2*PEEP of 1.50 (R2 = 0.75) best predicted CPAP failure. The risk of respiratory distress and early CPAP failure decreased 0.7 times per 1-week increase in gestational age and increased 1.7 times with every one-point decrease in Apgar score at 10 min and 19 times with FiO2*PEEP > 1.50 (vs. ≤ 1.50) at 3 h (R2 of the overall model = 0.83).

Conclusion: In moderate-to-late preterm infants, the combination of singleton pregnancy, lower Apgar score at 10 min, and FiO2*PEEP > 1.50 at 3 h can predict early CPAP failure with increased accuracy.

What is Known: |

•Respiratory distress syndrome (RSD) represents an unmet medical need in moderate-to-late preterm births and is commonly treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) to reduce mortality and the need for additional ventilatory support. |

• Optimal management of RSD is yet to be established, with several studies suggesting that identification of predictive factors for CPAP failure can aid in the prompt treatment of infants likely to experience this failure. |

What is New: |

•Secondary analysis of the observational NEOBS study indicated that oxygen requirements during CPAP therapy, especially the product of fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), are important factors associated with early CPAP failure in moderate-to-late term preterm infants. |

•The combination of a singleton pregnancy, low Apgar score at 10 minutes, and high FiO2*PEEP at 3 hours can predict early CPAP failure with increased accuracy, highlighting important areas for future research into the prevention of CPAP failure. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Moderate and late preterm births, occurring at 32–33 or 34–36 weeks of gestation (WG), respectively, account for the vast majority (≈85%) of all preterm births, representing about 13 million preterm infants per year worldwide [1].

While less common in moderate and late preterm infants compared with infants born extremely or very preterm, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is still an important issue in this population [2, 3]. In a contemporary cohort of late preterm and term births, late preterm birth was associated with increased risk for RDS and other respiratory morbidities [4].

Treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) has been shown to reduce mortality and the need for additional ventilatory support in preterm infants with respiratory distress [5]. Immediate initiation of nasal CPAP in the delivery room is recommended for all spontaneously breathing preterm infants with any clinical sign suggesting RDS [6,7,8]. Initial positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) should be started at 6–8 cmH2O and then individually titrated based on clinical condition, oxygenation, and perfusion [6, 7]. However, the level and quality of evidence for these recommendations are moderate to low, and optimal management of RDS in moderate-to-late preterm infants is yet to be established. Consistent with the recommendations for RDS, widespread use of CPAP in moderate-to-late preterm infants in France was recently documented in the multi-center, prospective, observational NEOBS study [9]. In this cohort study, the most common etiologies of respiratory failure in the overall population were transient tachypnea (57.3%) and RDS (39.8%). Surfactant therapy was administered to 22.5% of the total population, and 16.4% required mechanical ventilation [9].

Several studies have specified that identification of predictive factors for CPAP failure would be useful for the prompt treatment of infants likely to experience CPAP failure [10,11,12]. Therefore, the aim of the present analysis was to identify early factors associated with CPAP failure in moderate-to-late preterm infants from the NEOBS cohort study.

Methods

Study design and population

The study design and participant eligibility criteria for the NEOBS study have been reported previously [9]. The NEOBS study was a multi-center, prospective, observational study that was conducted in 46 neonatal intensive care units (level 2 or 3) in France [9]. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The NEOBS study received ethical approval from the West V Rennes Research Ethics Committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes, CPP) in October 2017 [9].

Study data were collected between 6 February 2018 and 28 November 2018. Infants were eligible for inclusion if they were born between 32 + 0/7 and 36 + 6/7 WG, had respiratory distress that required ventilatory support with CPAP within the first 24 h of life, were hospitalized at the investigating site within the first 24 h of life, and if informed consent to participate were obtained from either the parents or legal guardians. Infants were excluded if they required ventilatory support for an indication other than respiratory distress or a malformation disorder, required tracheal intubation prior to initiating CPAP treatment in the delivery room, died within the first 24 h, or were enrolled in a clinical trial involving ventilatory care impact. Infants with respiratory distress were treated according to current guidelines [6, 7]. Scheduled study visits occurred at 72 h (visit 1), day 7 (visit 2), and at hospital discharge to home (visit 3) or on day 60 (if the infant was still in hospital).

Study objective

The objective was to identify early factors (within the first 3 h of life) associated with CPAP failure, defined as the need for tracheal intubation within 72 h of CPAP initiation. The variables analyzed were maternal and neonatal clinical parameters in the delivery room, as well as clinical data at 3 h of life.

Assessments and data collection

Data were recorded by local investigators using an electronic case report form. Maternal, pregnancy, and delivery characteristics were recorded, as well as management in the delivery room, ventilatory support used, duration of ventilation, maximum fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) value, maximum PEEP value, the product of maximum FiO2 and PEEP (FiO2*PEEP), surfactant administration, and time to withdrawal of all respiratory support. Infants were followed up for at least 7 days after birth, until hospital discharge or until day 60 (if the infant was still in hospital).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses of qualitative variables comprise the number of patients and percentage for each category. Descriptive analyses of quantitative variables comprise mean and standard deviation. Logistic regression models were created to identify factors predictive of early CPAP failure based on variables of clinical interest. All potentially explanatory variables were tested in univariate analyses using the Student’s t-test if the normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilk test) and the assumption of homogeneity of variance were verified, the Satterthwaite method if the variances were unequal, or the Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney non-parametric test if the assumptions were not verified. The comparison of a categorical variable between two independent groups was assessed with the Pearson’s Chi-square test. Variables with p < 0.20 were included in the multiple logistic regression model; stepwise selection was performed on adjusted variables to eliminate those with an overall p value > 0.05. Gestational weeks, instead of birth weight, were used for logistic regression as European neonatologists have a preference for gestational weeks. The performance of the logistic regression analysis model was evaluated by assessing the area under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used, when required. Analyses were performed using the available data, with no imputation of missing data. SAS® software (version 9.4, SAS Institute, North Carolina USA) was used for performing statistical analyses.

Results

Participants

Of the 560 participants in the main NEOBS study, 418 were moderate-to-late preterm infants and 375 were treated with CPAP within 24 h of delivery without a prior invasive ventilation attempt (Fig. 1). Of these, 121 infants (32.3%) were moderate preterm and 254 (67.7%) were late preterm.

CPAP failure

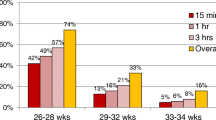

CPAP failure occurred in 45/375 neonates (12%). There were notable differences in characteristics between infants with CPAP failure and CPAP success (Table 1). The proportion of singletons with CPAP failure was substantially higher than the proportion of twins who had CPAP failure. In the CPAP failure group, the proportion of newborn infants with an Apgar score < 7 at 5 min was higher (22.2% compared with 6.1% in the success group; p = 0.01) and the mean Apgar score at 10 min was lower (Table 1). Other significant differences between those with CPAP failure versus CPAP success included a higher maximum FiO2 at 3 h of life (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1; Online Resource 1), a higher use of PEEP of ≥ 6 cmH20 at 3 h of life, a more frequent pH of < 7.2 from 0 to 24 h, and a more frequent carbon dioxide pressure (pCO2) > 60 mmHg from 0 to 24 h. No differences were identified between clinically relevant characteristics, such as the Silverman score or intrauterine growth retardation. There were several significant differences in the time course of respiratory support between neonates with CPAP failure versus CPAP success (Supplementary Table S2; Online Resource 1). For example, the proportion of infants with maximum FiO2 > 21% was significantly higher among infants with CPAP failure than in those with CPAP success at all evaluated timepoints, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of life.

There were few notable differences in treatment approaches between infants with CPAP failure and CPAP success (Supplementary Table S3; Online Resource 1). A significantly higher proportion of infants with CPAP failure were administered surfactant within 24 h of birth (77.8% vs 6.4% with CPAP success; p < 0.0001).

Cut-off for FiO2 and FiO2*PEEP associated with early CPAP failure

Optimal cut-off values for FiO2 and FiO2*PEEP at 3 h after delivery were determined from ROC curve analysis. The best R2 value (0.73) was found at a FiO2 cut-off value of 0.23, and an R2 value of 0.75 was found at a FiO2*PEEP cut-off value of 1.50 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Prediction of early CPAP failure

Table 2 presents results of the multivariate logistic model. Four early variables (those occurring in the first 3 h of life) were observed and entered in the backward logistic regression analysis.

Of the four variables entered in the logistic regression analysis (gestational age, type of pregnancy, Apgar score at 10 min, and FiO2*PEEP at 3 h), gestational age was forced and only type of pregnancy was not retained in the final model (Table 2).

Gestational age was a significant independent protecting factor for early CPAP failure (i.e., every one week increase, odds ratio (OR) = 0.703; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.493–1.004; p = 0.0526). In contrast, a lower Apgar score at 10 min (i.e., every one-point decrease; OR = 1.725; 95% CI 1.148–2.591; p = 0.0086) was a significant independent risk factor for early CPAP failure (Table 2). Neither FiO2 nor FiO2*PEEP in the delivery room was significant risk factors for early CPAP failure, based on univariate analyses. However, FiO2*PEEP > 1.50 at 3 h (vs. ≤ 1.50; OR = 18.660; 95% CI 7.158–48.640; p < 0.0001) was a significant independent risk factor for early CPAP failure (Table 2). A higher FiO2*PEEP at 3 h was thus the strongest factor associated with CPAP failure. The overall model had an area under ROC curve of 0.83, suggesting that all variables combined together can predict early CPAP failure with increased accuracy (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, NEOBS is the first study to investigate the factors associated with CPAP failure, including maternal and neonatal clinical characteristics, type of pregnancy and delivery, respiratory parameters (maximum FiO2 and PEEP), and in moderate-to late preterm infants. In this subgroup analysis of the NEOBS study, 12% of moderate-to-late preterm infants had CPAP failure requiring mechanical ventilator support or surfactant administration. Of note, the rate of CPAP failure was lower in our study than in previous studies in extreme or very early preterm infants (20–45%) [12, 13]. This difference in CPAP failure rate could be due to differences in gestational age, patient selection criteria, and treatment approaches. The proportion of patients with FiO2 > 21% and FiO2*PEEP > 1.05, > 1.25, > 1.50, and > 1.80 at each time point during respiratory support was significantly higher among infants with CPAP failure versus those with CPAP success.

Our analysis identified the following key characteristics associated with CPAP failure among moderate-to-late preterm infants: type of pregnancy (singleton vs. multiple), decrease in Apgar score at 10 min, and FiO2 and FiO2*PEEP at 3 h of life. Using ROC curve analysis, we identified FiO2 with a low cut-off of 23% at 3 h after delivery as the strongest factor associated with CPAP failure. These findings in moderate-to-late preterm infants are consistent with those reported in earlier preterm infants (i.e., higher FiO2 at 2 h after delivery was a significant predictor of CPAP failure) [14]; notably, the FiO2 threshold in the previous study (29%) was higher than that in the current study (23%), perhaps reflecting the slightly different patient populations in terms of the degree of prematurity. In this study, the strongest factor associated with CPAP failure was the product of FiO2 and PEEP; the risk of CPAP increased 20 times in infants requiring FiO2*PEEP > 1.50 compared with those requiring FiO2*PEEP ≤ 1.50 at 3 h.

Previous studies have focused on the FiO2 threshold in preterm infants born at ≤ 32 WG and the association between FiO2 threshold and CPAP failure, including those by Dargaville and colleagues (FiO2 > 30% in the first few hours after birth in very preterm infants born at 25–32 WG) [13], De Jaegere and colleagues (FiO2 > 25% in the first couple of hours were significantly associated with CPAP failure in preterm infants born at < 30 WG) [15]; Rocha and colleagues (also in earlier preterm infants; FiO2 of 40% in the first 4 h of life was a significant predictor of CPAP failure in preterm infants born at 26–30 WG) [16], Murki and colleagues (FiO2 of 40% at CPAP initiation was a significant predictor of CPAP failure in infants born at ≤ 32 WG) [11], and Dell’Orto and colleagues (FiO2 of 23% was highly predictive of CPAP failure in infants born at 24–32 WG) [10]. Higher FiO2 requirements have also been shown to predict failure of bilevel positive airway pressure therapy in late preterm infants with respiratory distress [17]. Overall, the current analysis completes the findings of previous studies and extends knowledge to infants born moderate or late preterm.

Our analysis revealed no significant differences in maternal antenatal corticosteroid treatment between infants with CPAP failure and CPAP success. Although the antenatal use of corticosteroids, even at ≥ 34 WG, reduces neonatal respiratory morbidity [18], corticosteroids are generally not recommended in women at risk of preterm delivery beyond 34 WG [6].

Singletons appeared to be at a higher risk of early CPAP failure than twins in our univariate analysis, but this statistical association did not remain in the multivariate model. This may be due to differences in the underlying cause of preterm birth, as multiple pregnancy alone is a common cause of moderate preterm birth for twins; therefore, physicians were better prepared to manage the respiratory problems associated with premature birth. However, this is not the case for singletons, who might instead have a specific underlying risk factor (or factors, e.g., maternal factors such as smoking during pregnancy, maternal age, and hypertension or diabetes in pregnancy) [19], which could have additional impacts on respiratory health in the neonatal period. This is something that needs to be investigated further. Additionally, the risk of CPAP failure increased 1.7 times with every one-point decrease in Apgar score at 10 min; however, this factor may only be helpful for a few individual risk assessments, as the Apgar scores were > 7 at 10 min in the majority of infants.

In our analysis, we observed low rates of surfactant use in the delivery room. Early INSURE therapy has been shown to reduce the rate of CPAP failure in infants born at 33 to 36 + 6/7 WG [20]. In the same way, less invasive surfactant administration (LISA) has been shown to prevent early CPAP failure, even if most of the infants included were < 32 WG [21,22,23]. In this study, only four infants received surfactant via the LISA method, but they did not have CPAP failure. As previously reported, the centers including in the NEOBS study were only starting to use LISA method [9]. A new study incorporating the LISA method along with the recent guidelines [6, 7] would be interesting.

This study has several limitations. This is a post hoc analysis of data of 375 moderate-to-late preterm infants from an observational study; although associations can be determined, no conclusions can be drawn regarding causality. There is also limited external generalizability due to all study participants being recruited at level 2 and 3 maternity centers in a single high-income country (France). Nevertheless, there are limited data on respiratory failure in late preterm infants. The strength of this study is the large population size that included participants from most of the regions of France. Moreover, being an observational study, it reflects current clinical practice in France and its impact on clinical outcomes of infants. In addition, we used a respiratory score (FiO2*PEEP) rather than other calculations, such as the oxygenation index (mean airway pressure*FiO2*100/partial pressure of oxygen [PaO2]). Even if this score cannot assess severity of hypoxic respiratory failure, it is a good approximation of PaO2 and can be used in clinical practice to maintain a normal oxygen saturation for the newborn infant, according to international guidelines [6, 7]. Further epidemiological studies, machine learning algorithms, or new tools such as lung ultrasound are required for an optimal individual assessment of CPAP failure and early specific treatments, such as surfactants [24,25,26].

In conclusion, oxygen requirement during CPAP therapy, especially the product of FiO2 and PEEP, was an important factor associated with early CPAP failure in moderate-to-late preterm infants. The combination of singleton pregnancy, low Apgar score at 10 min, and high FiO2*PEEP at 3 h can predict early CPAP failure with increased accuracy. Our study also highlighted important areas for future research into the prediction or prevention of CPAP failure.

Data availability

Data generated/analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CNIL:

-

Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertes

- CPAP:

-

Continuous positive airway pressure

- CPP:

-

Comité de Protection des Personnes

- FiO2 :

-

Fraction of inspired oxygen

- H2O:

-

Dihydrogen oxide (water)

- INSURE:

-

Intubate surfactant extubate

- LISA:

-

Less invasive surfactant administration

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- pCO2 :

-

Carbon dioxide pressure

- PEEP:

-

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- RDS:

-

Respiratory distress syndrome

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristics

- USA:

-

Unites States of America

- WG:

-

Weeks of gestation

References

Torchin H, Ancel PY (2016) Épidémiologie et facteurs de risque de la prématurité. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 45:1213–1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgyn.2016.09.013

Escobar GJ, Clark RH, Greene JD (2006) Short-term outcomes of infants born at 35 and 36 weeks gestation: we need to ask more questions. Semin Perinatol 30:28–33. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2006.01.005

Karnati S, Kollikonda S, Abu-Shaweesh J (2020) Late preterm infants - changing trends and continuing challenges. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med 7:36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpam.2020.02.006

Hibbard JU, Wilkins I, Sun L, Gregory K, Haberman S, Hoffman M, Kominiarek MA, Reddy U, Bailit J, Branch DW et al (2010) Respiratory morbidity in late preterm births. JAMA 304:419–425. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1015

Ho JJ, Subramaniam P, Davis PG (2020) Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for respiratory distress in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10:Cd002271. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002271.pub3

Sweet DG, Carnielli V, Greisen G, Hallman M, Ozek E, Te Pas A, Plavka R, Roehr CC, Saugstad OD, Simeoni U et al (2019) European Consensus Guidelines on the management of respiratory distress syndrome - 2019 update. Neonatology 115:432–450. https://doi.org/10.1159/000499361

Madar J, Roehr CC, Ainsworth S, Ersdal H, Morley C, Rüdiger M, Skåre C, Szczapa T, Te Pas A, Trevisanuto D et al (2021) European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: newborn resuscitation and support of transition of infants at birth. Resuscitation 161:291–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.014

World Health Organization (2015) WHO recommendations on interventions to improve preterm birth outcomes. Accessed 06 April 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/183037/9789241508988_eng.pdf

Debillon T, Tourneux P, Guellec I, Jarreau PH, Flamant C (2021) Respiratory distress management in moderate and late preterm infants: the NEOBS study. Arch Pediatr 28:392–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2021.03.010

Dell’Orto V, Nobile S, Correani A, Marchionni P, Giretti I, Rondina C, Burattini I, Palazzi ML, Carnielli VP (2021) Early nasal continuous positive airway pressure failure prediction in preterm infants less than 32 weeks gestational age suffering from respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Pulmonol 56:3879–3886. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.25678

Murki S, Kandraju H, Oleti T, Saikiran GP (2020) Predictors of CPAP failure – 10 years’ data of multiple trials from a single center: a retrospective observational study. Indian J Pediatr 87:891–896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-020-03399-5

Dargaville PA, Gerber A, Johansson S, De Paoli AG, Kamlin COF, Orsini F, Davis PG, Australian ft, Network NZN (2016) Incidence and outcome of CPAP failure in preterm infants. Pediatrics 138. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3985

Dargaville PA, Aiyappan A, De Paoli AG, Dalton RG, Kuschel CA, Kamlin CO, Orsini F, Carlin JB, Davis PG (2013) Continuous positive airway pressure failure in preterm infants: incidence, predictors and consequences. Neonatology 104:8–14. https://doi.org/10.1159/000346460

Gulczyńska E, Szczapa T, Hożejowski R, Borszewska-Kornacka MK, Rutkowska M (2019) Fraction of inspired oxygen as a predictor of CPAP failure in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective multicenter study. Neonatology 116:171–178. https://doi.org/10.1159/000499674

De Jaegere AP, van der Lee JH, Canté C, van Kaam AH (2012) Early prediction of nasal continuous positive airway pressure failure in preterm infants less than 30 weeks gestation. Acta Paediatr 101:374–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02558.x

Rocha G, Flôr-de-Lima F, Proença E, Carvalho C, Quintas C, Martins T, Freitas A, Paz-Dias C, Silva A, Guimarães H (2013) Failure of early nasal continuous positive airway pressure in preterm infants of 26 to 30 weeks gestation. J Perinatol 33:297–301. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2012.110

Son H, Choi EK, Park KH, Shin JH, Choi BM (2020) Risk factors for BiPAP failure as an initial management approach in moderate to late preterm infants with respiratory distress. Clin Exp Pediatr 63:63–65. https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2019.01361

Saccone G, Berghella V (2016) Antenatal corticosteroids for maturity of term or near term fetuses: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ 355:i5044. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5044

Xu XK, Wang YA, Li Z, Lui K, Sullivan EA (2014) Risk factors associated with preterm birth among singletons following assisted reproductive technology in Australia 2007–2009–a population-based retrospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14:406. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-014-0406-y

Alarcón-Olave MC, Gómez-Ochoa SA, Jerez-Torra KA, Martínez-González PL, Sarmiento-Villamizar DF, Rojas-Devia MA, Pérez-Vera LA (2021) Early INSURE therapy reduces CPAP failure in late preterm newborns with respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatria 54:4–11

Abdel-Latif ME, Davis PG, Wheeler KI, De Paoli AG, Dargaville PA (2021) Surfactant therapy via thin catheter in preterm infants with or at risk of respiratory distress syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5:Cd011672. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011672.pub2

Bellos I, Fitrou G, Panza R, Pandita A (2021) Comparative efficacy of methods for surfactant administration: a network meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 106:474–487. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2020-319763

Isayama T, Iwami H, McDonald S, Beyene J (2016) Association of noninvasive ventilation strategies with mortality and bronchopulmonary dysplasia among preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 316:611–624. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.10708

Brat R, Yousef N, Klifa R, Reynaud S, Shankar Aguilera S, De Luca D (2015) Lung ultrasonography score to evaluate oxygenation and surfactant need in neonates treated with continuous positive airway pressure. JAMA Pediatr 169:e151797. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1797

Raimondi F, Migliaro F, Corsini I, Meneghin F, Pierri L, Salomè S, Perri A, Aversa S, Nobile S, Lama S et al (2021) Neonatal lung ultrasound and surfactant administration: a pragmatic, multicenter study. Chest 160:2178–2186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.076

Leon C, Cabon S, Patural H, Gascoin G, Flamant C, Roue JM, Favrais G, Beuchee A, Pladys P, Carrault G (2022) Evaluation of maturation in preterm infants through an ensemble machine learning algorithm using physiological signals. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 26:400–410. https://doi.org/10.1109/jbhi.2021.3093096

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nicola Ryan who wrote the outline of this manuscript on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications and Mitali Choudhury, PhD, of Springer Healthcare Communications who wrote the first draft. This medical writing assistance was funded by Chiesi France.

Funding

This study, medical writing support, and the article processing charges were funded by Chiesi SAS France. All authors had full access to all the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pierre Tourneux, Thierry Debillon, Cyril Flamant, Pierre-Henri Jarreau, Benjamin Serraz, and Isabelle Guellec were involved in patient enrolment, study conceptualization, methodology, formal investigation, formal analysis of the data, and critical review and revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript as submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The NEOBS study received ethical approval from the West V Rennes Research Ethics Committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes, CPP) in October 2017.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent to participate was obtained from either the parents or legal guardians of the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Pierre Tourneux, Thierry Debillon, Cyril Flamant, Pierre-Henri Jarreau, and Isabelle Guellec have received speaker fees or honoraria from Chiesi. Benjamin Serraz was an employee of Chiesi SAS, France, at the time of the preparation of this manuscript.

Additional information

Communicated by Daniele De Luca

Preliminary results presented at the 8th Congress of the European Academy of Paediatric Societies, held in Barcelona, Spain, from 16–20 October 2020.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tourneux, P., Debillon, T., Flamant, C. et al. Early factors associated with continuous positive airway pressure failure in moderate and late preterm infants. Eur J Pediatr 182, 5399–5407 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05090-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05090-1