Abstract

There are increasing numbers of refugee and asylum-seeking children entering the UK annually who face significant barriers to accessing healthcare services. Clinicians working in the emergency department should have an awareness of the journeys children may have taken and the barriers they face in accessing care and have a holistic approach to care provision. We conducted a narrative literature review and used experiential knowledge of paediatricians working in the Paediatric Emergency Department to formulate a step-by-step screening tool. We have formulated a step-by-step screening tool, CCHILDS (Communication, Communicable diseases, Health—physical and mental, Immunisation, Look after (safeguarding), Deficiencies, Sexual health) which can be used by healthcare professionals in the emergency department.

Conclusion: Due to increasing numbers of refugee and asylum-seeking children, it is important that every point of contact with healthcare professionals is an impactful one on their health, well-being and development. Future work would include validation of our tool.

What is Known: |

•The number of refugees globally are rapidly increasing, leading to an increase in the number of presentations to the PED. These patients are often medically complex and may have unique and sometimes unexpected presentations that could be attributed to by their past. There are a multitude of resources available outlining guidance on the assessment and management of refugee children. |

What is New: |

•This review aims to succinctly summarise the guidance surrounding the assessment of refugee children presenting to the PED and ensure that healthcare professionals are aware of the pertinent information regarding this cohort. It introduces the CCHILDS assessment tool which has been formulated through a narrative review of the literature and acts as a mnemonic to aid professionals in their assessment of refugee children in the PED. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The number of refugees worldwide has increased considerably due to ongoing wars, national instability, climate change, political persecution and food and economic insecurity [1]. The countries of origin of refugees and asylum seekers have varied over recent years, depending on factors including political crises, war, conflicts and climate emergencies [2]. For example, the recent turmoil in Ukraine has led to the evacuation of thousands of refugees and asylum seekers [2]. Within the UK, as of September 2022, the top five countries for asylum applications included Iran (6002), Eritrea (4412), Albania (4010), Iraq (3042) and Syria (2303) [1]. By the end of 2022, almost 40% of refugees globally are children and adolescents under the age of 18 [3]. In 2018, 74% of UASC were 16–17 years old, 21% were 14–15, whilst 2% were under 14 with a total of 89% of applicants being male [4, 5].

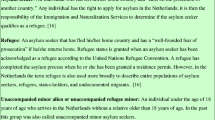

Refugee and asylum-seeking children (Table 1) face significant risks to their health and therefore may have complex health needs [6]. Therefore, establishing holistic care for refugee and asylum-seeking children can have widespread positive implications and may shape their transition into a new country.

Within their country of origin, war, political conflict and human rights violations may have resulted in a lack of adequate healthcare which can lead to undiagnosed or untreated chronic conditions, an increased risk of vaccine-preventable communicable diseases, nutritional deficiencies, STIs and mental health issues [7]. Moreover, the unsafe journey can lead to serious health complications such as hypothermia, infections, malnutrition, dehydration and traumatic injuries [8].

There is also a high prevalence of mental health issues across refugee and asylum-seeking children including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety disorders from either witnessing or suffering traumatic experiences such as sexual abuse and violence, isolation and the burden of leaving family in their home country [9].

A notable study by Nijman et al. [10] found that there is a necessity for improved guidance, educational tools and a platform for shared learning on managing refugee children in emergency care. There are multiple obstacles faced to accessing healthcare including language barriers, financial limitations and a lack of trust in the system. Furthermore, numerous system obstacles are faced which include frequent relocations, administrative issues and a fear of health information being shared with the Home Office for refused asylum seekers. This paper aims to provide a concise summary of what paediatric emergency medicine healthcare professionals should know regarding the journey taken by refugee and asylum-seeking children and the barriers to accessing healthcare and provide a framework for assessing patients.

Key pre-consultation considerations

An awareness of the refugee or asylum-seeking child’s background and journey to the UK is necessary to provide effective, holistic care within the PED. We outline below key considerations. Please note it is not expected you would gather all the below information during a consultation. Rather, these are factors to consider when assessing children in the PED, ensuring culturally sensitive and trauma-informed practice.

-

Background

-

Life context of the child and family: religion, gender, ethnic origin and individual circumstances. They may have been exposed to several traumatic events during childhood which can predispose to the development of mental health conditions, which are later explored [11].

-

Reasons for migration and profile of the country of origin: main challenges, disease prevalence, impact of war and political crisis.

-

The healthcare access in the country of origin: what is the health infrastructure like (i.e. is healthcare free), what preventative care is in place?

-

Timeline of medical care from antenatal care to current presentation: likelihood of adequate antenatal screening (e.g. HIV, hepatitis B, foetal alcohol syndrome), access to postnatal screening routinely conducted in the UK (e.g. Guthrie test, new-born baby check and hearing screen) and vaccination schedules.

-

Refugee and asylum-seeking children may be malnourished and have micronutrient deficiencies.

-

-

During the journey

-

Consider route and mode of travel; however, be aware that many patients may be reluctant to share details.

-

Those travelling alone, especially women and children, are at a higher risk of sexual assault during their travel [12]. Hence, consider possible psychological distress, risk factors for blood-borne infections, STIs, urogenital damage and pregnancy.

-

Depending on the time spent in camps or other cramped conditions, there may be an increased risk of contracting TB and other infectious diseases.

-

-

Arrival to the UK

-

Refugee and asylum-seeking children and young people may be subject to frequent changes to their accommodation which can lead to disjointed healthcare.

-

There may be difficulties faced in accessing healthcare due to a lack of money and transportation.

-

Complex and lengthy immigration processes, frequent relocations, difficulties in accessing healthcare, education and other sources of support can all contribute to increased emotional distress.

-

Barriers to accessing healthcare

For those who settle in the UK, there are many barriers to accessing health and social care. There may be a lack of knowledge of their rights and entitlement within the UK health system; administrative barriers; and cultural and language barriers [12]. There may also be concerns about facing discrimination from healthcare professionals.

Rights and entitlement within the UK health system

Many refugee and asylum-seeking children are unaware of their rights and entitlement within the UK health system [13]. Although there is a lack of resources available to PED healthcare professionals regarding refugee and asylum-seeking children, efforts should be made to provide coherent information on the entitlement and rights to services at all points of contact. This empowers patients so that they can better advocate for themselves. The Refugee Council [14] provides a factsheet in multiple languages containing information on healthcare eligibility and access for people seeking asylum in the UK. Crucially, in England, there is no minimum time that a patient must reside in the UK to be eligible to receive NHS primary medical care services [13].

Despite those rights, there are well-documented barriers to accessing healthcare for this population. Administrative barriers, such as needing ID documents and proof of address to register at most GP surgeries, cause delays and denials of GP registration. It is vital to be aware that everyone should be able to access primary healthcare services without any documentation [15, 16]. NHS charging regulations, which exempt asylum seekers and refugees from charging, have been found to be at times inappropriately applied in this population leading to delays and denials of care [17]. Language barriers and the lack of readily available interpreters in all healthcare settings can cause further obstacles. Financial difficulties can also make it hard to get to appointments, particularly in secondary care. Frequent relocations in the UK by the Home Office can cause disjointed care provision. Finally, there may be well-founded reasons to distrust healthcare services, particularly as healthcare charging regulations can lead to sharing of information between healthcare settings and the Home Office, particularly for refused asylum seekers who are at risk of deportation [14].

The barriers described above can mean that asylum seekers and refugees are less likely to access healthcare in Emergency Departments.

PED consultation

A structured, comprehensive history should be taken with efforts to adopt a holistic approach towards the child and family. We have established a step-by-step screening tool (Fig. 1) and created the acronym CCHILDS to aid in the assessment of refugee and asylum-seeking children. This tool is not currently validated; however, it has been formulated to aid in the assessment of refugee and asylum-seeking children presenting to PED.

Methodology

The CCHILDS assessment tool (Fig. 1) was formulated through a narrative assessment of the literature on child and refugee health. A literature search of PUBMED, OVID Medline and OVID Embase was conducted to synthesise key evidence on refugee and asylum-seeking children health considerations. This was supplemented with a detailed Google search and reference searching to generate areas of focus in the assessment of the paediatric refugee or asylum-seeking children. The seven areas of focus we identified were the elimination of language barriers, screening for infectious diseases, physical health examination, immunisations, screening for safeguarding concerns, nutrition screening and sexual health. These areas were then streamlined into a mnemonic for ease of memory.

CCHILDS step-by-step acute healthcare screen

Communication

-

Use a professional, third-party interpreter, if required, to create a safe and trusting atmosphere [18]. If there are difficulties in ascertaining an appropriate interpreter immediately, mobile phone translation applications (e.g. Care to Translate) may be used to aid the consultation but used with caution and consideration as these applications are not validated and must not replace a professional interpreter [19].

-

Family members should not be used as interpreters as they are unlikely to provide neutral, unbiased opinions and there may be potential for exploitation.

-

-

Use trauma-informed care approaches in all encounters as many will have experienced traumatic events that will affect their health, mental health and all aspects of their lives. Trauma-informed care principles include safety, trust, choice, collaboration, empowerment and cultural consideration [20].

Communicable and parasitic diseases

Screening for infectious diseases should be guided by clinical presentation and risk. Screening is also recommended for asymptomatic communicable diseases since refugees and asylum seekers are at increased risk.

-

Asymptomatic screening includes (but is not exclusive to) tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis, HIV, sexually transmitted infections and parasitic infections [21].

-

Clinical evaluation of the most prevalent diseases from the country of origin should be considered when presented with symptoms. This can be aided by the Migrant A-Z guide [22] from Public Health England (Table 2) and it is advised to make appropriate referrals to infectious diseases.

-

Children or young people presenting from countries with an incidence of TB of, or greater than, 40/100,000 should be referred to paediatric TB or infectious diseases services for assessment [21]. Latent TB screening may also be conducted in PED.

-

If clinically indicated, it may also be relevant to screen for tropical parasitic diseases including bilharziasis, anguillulose and malaria.

-

Young people at risk of STIs and blood-borne viruses may be asymptomatic. Routinely offer to screen for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis, hepatitis B and C and HIV to reduce the risk of stigmatisation from target screening [18]. This could be followed up by the GP or by referral to appropriate secondary care services (e.g. paediatrics infectious diseases) dependent on the presentation.

-

For concerns about child sexual abuse, this needs to be escalated to seniors immediately and the local guidelines should be followed. This will include referral to social care and specialist child sexual abuse services.

Where appropriate, discussions around the importance of communicable disease testing should occur with the child/adolescent away from the bedside.

Health—physical and mental

-

Mental health:

-

In the acute setting, it is important to be aware that exploring previous traumatic experiences and psychological trauma is not routinely recommended; they are important considerations but should not be specifically questioned during the consultation unless the patient is presenting with an acute mental health condition. It is likely to cause additional distress on the child with no guaranteed social work or psychology follow-up.

-

If mental health is an acute issue on presentation, it is recommended to address this and refer to CAMHS. Third sector services (e.g. Refugee Council) can offer further support [14].

-

There are a multitude of considerations that may impact the child and contribute towards their presentation. These are summarised in specific guidance for paediatricians assessing refugee and asylum-seeking children, available on the RCPCH website [21].

-

-

Physical health:

-

Take a comprehensive history and conduct a thorough physical examination as would be done for any patient but with a particular focus on the following [23, 24]:

-

Malnutrition

-

Poorly managed chronic health conditions

-

Dental health—discuss any dental symptoms and signpost to attend NHS dental practice as soon as possible even if asymptomatic. Educate patients and families around the importance of oral hygiene and lifestyle choices such as smoking and alcohol which are associated with adverse oral health outcomes.

-

Access to vaccinations

-

Trauma and injury

-

Infections

-

Development

-

Lack of health screening and health promotion

-

Baseline bloods, nutrition screen, infectious disease screen

-

-

Immunisations

-

Establish vaccination history and provide information on the UK immunisation schedule [25].

-

If the vaccine history is uncertain, opportunistically vaccinate if possible and provide information on GP registration, recommending a full course of catch-up immunisations.

Look after—safeguarding

-

Immediate referral to local authority for all children presenting alone.

-

If there are indications of possible trafficking, sexual assault, female genital cutting, mental health issues or other safeguarding concerns, discuss with seniors and make appropriate referrals according to Local Hospital Guidelines. It is vital that these topics are discussed with a non-stigmatising approach with care taken regarding the language used (e.g. ‘mutilation’ may be found offensive with ‘cutting’ and ‘circumcision’ preferred internationally).

-

Exposure to violence, rape and/or other traumas should be explored sensitively. Not all young people are able to disclose on first assessment if they have been the victim of assault, and this will need careful inquiry. However, be aware that this may not always be relevant or appropriate in the PED setting with no formal follow-up. It is also important to differentiate between historical child protection concerns and current acute risk.

-

Be aware of cultural child protection concerns including the risk of underage/forced marriage and exposure to child labour which may be more prevalent in certain ethnic cohorts [26].

-

Safeguarding concerns may arise from an unsafe environment for the child in temporary accommodation or due to neglect or physical abuse [18].

-

For a young person experiencing bullying, racism and other forms of marginalisation, there is increased vulnerability to exploitation.

Deficiencies

-

Refugee and asylum-seeking children are at a high risk of malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies [27].

-

Food insecurity remains a common concern following resettlement in developed countries. Targeted, culturally appropriate parental education resources and interventions may help mitigate this following resettlement, although may not be clinically relevant in PED unless directly corresponding to the patient’s presentation [28].

-

Consider screening for anaemia, micronutrient and vitamin deficiencies when requesting blood tests. Be aware of micronutrient deficiencies such as vitamin B complex, vitamin A and zinc with night blindness being a common sign of vitamin A deficiency. It is also important to note that conditions such as vitamin D deficiency are more likely to lead to rickets in this cohort and hence, it is advisable to consider bowing of legs, widened wrist epiphyses and a soft skull in infants.

Sexual health

-

Signpost or offer to arrange referral for adolescent or ‘at-risk’ patients to local sexual health services. Test for HIV and hepatitis B and C in at-risk groups with consent.

-

Considerations must also be made regarding the adolescent’s reproductive health. Limited education, availability of preventative vaccines and contraception use may contribute to high-risk sexual behaviours and will increase the risk of unplanned pregnancies and STIs in this cohort. Be aware of cultural stigma regarding sexual and reproductive health and the impact this may have on the consultation [29].

-

If there is a concern about possible child sexual abuse (CSA), refer to social care and refer to local CSA services.

We appreciate that this is a vast amount to cover in a stretched PED with only 15 min per consultation. Although all the points are unlikely to be covered, it is important for the clinician to be aware of guidelines and the main considerations so that their consultation can be appropriately focussed on managing the specific needs of a refugee or asylum-seeking child where possible. In particular, the main take-away point for clinicians is to use a professional interpreter wherever there is limited English proficiency and not to use family or friends unless it is a life-threatening situation. Advice regarding the use of interpreters can be found on the GOV.UK website [30] and also on the BMA [31]. Furthermore, Migrants Organise [32] have issued a “Good practice guide to interpreting” which is useful for both clinicians and patients alike and available in a multitude of languages.

Discharge from PED: things to consider

Upon discharge from the PED, there are important considerations universal to all paediatric refugee and asylum-seeking children.

-

1.

Explain how the NHS works and entitlement to care

-

(a)

Refugees and asylum seekers are eligible to receive all NHS care free of charge [33].

-

(b)

Explain the range of NHS services available including emergency, primary and secondary care [34].

-

(c)

Social care depends on the local authority guidelines and appointment of a social worker is conducted on a case-by-case basis.

-

(d)

All children in the process of claiming asylum or have been granted refugee status have access to education. UASC will have an allocated social worker.

-

(e)

Provide discharge letters to ensure they have all documentation should the patient be transferred elsewhere. This may be subject to decision by the Home Office.

-

(a)

-

2.

Consider acute referrals if appropriate, for example to secondary care, CAMHS or social services as many children will not be registered with GP.

-

(a)

Social workers can support with GP registrations and can make CAMHS referrals if needed.

-

(b)

Consider arranging secondary care paediatric follow-up if needed whilst awaiting GP registration.

-

(a)

-

3.

Facilitate registration with a GP

-

(a)

Explain that registration with a GP is free and encourage this. There are leaflets by Doctors of the World [35] (Table 2) that can be printed out for the patient to take to the GP.

-

(b)

Identify local GP via the ‘Find a GP’ NHS site [36] or register using a GMS1 form [37]. Print their discharge summary and a written note to the GP explaining the patient’s current situation and why they need registration.

-

(i)

Alternatively, call ‘Doctors of the World’ and book into one of their free clinics [38].

-

(i)

-

(a)

-

4.

Be mindful of financial limitations

-

(a)

Consider prescribing over-the-counter medications, being mindful of monetary limitations commonly faced by refugee and asylum-seeking children (the UK government currently issues £40.85 per week to each refugee to help pay towards food, clothing, toiletries and all other basic necessities) [39]. Prescriptions for children are free of charge and adults would need a HC2 certification for evidence of exemption [40].

-

(a)

-

5.

Social and education considerations

Limitations and scope for future work

There are several limitations of this review. Firstly, this is a narrative review in practice aimed at providing a practical approach to the assessment of refugee and asylum-seeking children and therefore may not have captured evidence that may have been synthesised in a systematic review. In addition, the CCHILDS tool has been formulated using the literature on refugee and asylum-seeking children; however, this tool has not been validated.

Future work could look at validating the CCHILDS tool and evaluating its use in PED settings.

Summary

Facilitating quality healthcare to refugee and asylum-seeking children is key to aiding health, well-being and development. With increasing numbers of refugee children, the opportunities for positive impact at each point of contact is essential. We recommend adopting the CCHILDS approach for the clinical evaluation of paediatric refugees and asylum seekers who present to the PED.

Abbreviations

- CAMHS:

-

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services

- CCHILDS:

-

Communication, Communicable diseases, Health-physical and mental, Immunisations, Look after-safeguarding, Deficiencies, Sexual health

- GP:

-

General Practice

- PED:

-

Paediatric Emergency Department

- RCPCH:

-

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

- STIs:

-

Sexually transmitted infections

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- UASC:

-

Unaccompanied asylum-seeking children

References

Refugee crisis: 100 million displaced [Internet] (2023). International Rescue Committee (IRC). Available from: https://www.rescue.org/topic/refugee-crisis-100-million-displaced

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Asylum-seekers [Internet]. UNHCR. 2018. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/asylum-seekers.html

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (no date) Refugee statistics, UNHCR. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ (Accessed: 01 June 2023)

Baauw A, Kist-van Holthe J, Slattery B, Heymans M, Chinapaw M, van Goudoever H (2019) Health needs of refugee children identified on arrival in reception countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Paediatrics Open 3(1):e000516

Information Children in the Asylum System [Internet] (2019) Available from: https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Children-in-the-Asylum-System-May-2019.pdf

Kadir A, Battersby A, Spencer N, Hjern A (2019) Children on the move in Europe: a narrative review of the evidence on the health risks, health needs and health policy for asylum seeking, refugee and undocumented children. BMJ Paediatrics Open 3(1):bmjpo-2018–000364

Hunter P (2016) The refugee crisis challenges national health care systems. EMBO reports [Internet] 17(4):492–5. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.15252/embr.201642171

Migration and health: key issues [Internet] (2022). www.euro.who.int. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/migration-and-health/migration-and-health-in-the-european-region/migration-and-health-key-issues

Yayan EH, Düken ME, Özdemir AA, Çelebioğlu A. Mental health problems of Syrian refugee children: post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2019 Jun;51.

Nijman RG, Krone J, Mintegi S, Bidlingmaier C, Maconochie IK, Lyttle MD, et al. Emergency care provided to refugee children in Europe: RefuNET: a cross-sectional survey study. Emergency Medicine Journal [Internet]. 2021 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Mar 6];38(1):5–13. Available from: https://emj.bmj.com/content/38/1/5

Hanes G, Sung L, Mutch R, Cherian S (2017) Adversity and resilience amongst resettling Western Australian paediatric refugees. Journal of Paediatric Child Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13559

Guidelines on Prevention and Response. Sexual violence against refugees [Internet] (1995). Available from: https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/3ae6b33e0.pdf

Asgary R, Segar N (2011) Barriers to health care access among refugee asylum seekers. J Health Care Poor Underserved 22(2):506–522

Kang C, Tomkow L, Farrington R. Access to primary health care for asylum seekers and refugees: a qualitative study of service user experiences in the UK. British Journal of General Practice [Internet]. 2019 Feb 11;69(685):e537–45. Available from: https://bjgp.org/content/69/685/e537

Refugee Council. The truth about asylum - Refugee Council [Internet] (2019) Refugee Council. Available from: https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/information/refugee-asylum-facts/the-truth-about-asylum/

Hargreaves S, Holmes AH, Saxena S, Le Feuvre P, Farah W, Shafi G, et al. Charging systems for migrants in primary care: the experiences of family doctors in a high-migrant area of London. Journal of Travel Medicine [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2023 Mar 6];15(1):13–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18217864

Making sure people seeking and refused asylum can access healthcare: what needs to change? [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 6]. Available from: https://www.doctorsoftheworld.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/people-seeking-asylum-access-to-healthcare-what-needs-to-change-1.pdf

Murphy L, Broad J, Hopkinshaw B, Boutros S, Russell N, Firth A et al (2020) Healthcare access for children and families on the move and migrants. BMJ Paediatrics Open 4(1):e000588

Sarfraz S, Wacogne ID (2018) Fifteen-minute consultation: how to use an interpreter in a medical consultation. Archives of disease in childhood - Education & practice edition 104(5):231–234

Panayiotou A, Gardner A, Williams S, Zucchi E, Mascitti-Meuter M, Goh AM, You E, Chong TW, Logiudice D, Lin X, Haralambous B, Batchelor F. Language translation apps in health care settings: expert opinion. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019 Apr 9;7(4):e11316. https://doi.org/10.2196/11316. PMID: 30964446; PMCID: PMC6477569

Gov.UK. Working definition of trauma-informed practice [Internet]. GOV.UK. 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/working-definition-of-trauma-informed-practice/working-definition-of-trauma-informed-practice

Refugee and asylum seeking children and young people - guidance for paediatricians [Internet]. RCPCH. (2018) Available from: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/refugee-asylum-seeking-children-young-people-guidance-paediatricians#overview-of-at-risk-communicable-diseases

Migrant health guide: countries A to Z [Internet]. GOV.UK. (2023) Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/migrant-health-guide-countries-a-to-z

Chaves NJ, Paxton G, Biggs BA, Thambiran A, Smith M, Williams J, Gardiner J, Davis JS; on behalf of the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases and Refugee Health Network of Australia Guidelines writing group. Recommendations for comprehensive post-arrival health assessment for people from refugee-like backgrounds; Second Edition (2016) Australasian Society of Infectious Diseases. Australia, Sydney

Child and adolescent health: a resource of the Australia Refugee Health Practice Guide (2018) Accessed: http://refugeehealthguide.org.au/wpcontent/uploads/ARHPG_BOOK_2_CHILD_A4_FA_web.pdf

The UK Immunisation Schedule | Vaccine Knowledge [Internet]. Ox.ac.uk. (2018) Available from: https://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/vk/uk-schedule

Lindsay K, Hanes G, Mutch R, McKinnon E, Cherian S (2022) Looking beyond: complex holistic care needs of Syrian and Iraqi refugee children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child 107(5):461–467. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2021-322718. Epub 2021 Oct 26 PMID: 34702714

Gibson J, Evennett J (2018) The health needs of asylum-seeking children. Br J Gen Pract 68(670):238–248

Newman K, O’Donovan K, Bear N, Robertson A, Mutch R, Cherian S (2019) Nutritional assessment of resettled paediatric refugees in Western Australia. J Paediatr Child Health 55(5):574–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.14250. Epub 2018 Oct 5 PMID: 30288837

Hirani K, Payne D, Mutch R, Cherian S (2016) Health of adolescent refugees resettling in high-income countries. Arch Dis Child 101(7):670–676. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-307221. Epub 2015 Oct 15 PMID: 26471111

Language interpreting and translation: migrant health guide (no date) GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/language-interpretation-migrant-health-guide (Accessed: 01 June 2023).

The BMA. Managing language barriers for refugees and asylum seekers - refugee and asylum seeker patient health toolkit - BMA, The British Medical Association is the trade union and professional body for doctors in the UK. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/ethics/refugees-overseas-visitors-and-vulnerable-migrants/refugee-and-asylum-seeker-patient-health-toolkit/managing-language-barriers-for-refugees-and-asylum-seekers (Accessed: 01 June 2023).

Migrants Organise (2023) Good practice guide to interpreting-English, Migrants Organise. Available at: https://www.migrantsorganise.org/good-practice-guide-to-interpreting-english-2/ (Accessed: 01 June 2023).

BMA. Refugees’ and asylum seekers’ entitlement to NHS Care - refugee and asylum seeker patient health toolkit - BMA [Internet]. The British Medical Association Is the Trade Union and Professional Body for Doctors in the UK. 2021. Available from: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/ethics/refugees-overseas-visitors-and-vulnerable-migrants/refugee-and-asylum-seeker-patient-health-toolkit/refugees-and-asylum-seekers-entitlement-to-nhs-care

The Kings Fund. The King’s Fund [Internet]. The King’s Fund. The King’s Fund; 2017. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/how-does-nhs-in-england-work

Refugees and migrants [Internet]. Doctors of the World. (2023) Available from: https://www.doctorsoftheworld.org.uk/who-we-are/refugees-and-migrants/

Find a GP - NHS [Internet] (2023) www.nhs.uk. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/service-search/find-a-gp

Family doctor services registration GMS1 patient’s details [Internet]. (2019) Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/826307/GMS1-family-doctor-services-registration-form.pdf

Patient Clinic [Internet]. Doctors of the World. [cited 2023 Mar 6]. Available from: https://www.doctorsoftheworld.org.uk/patient-clinic/

Gov.uk. Asylum support [Internet]. GOV.UK. 2012. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/asylum-support/what-youll-get

HC2 certificates (full help with health costs) | NHSBSA [Internet] (2023) www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk. Available from: https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/nhs-low-income-scheme/hc2-certificates-full-help-health-costs

Vaghri Z, Tessier Z, Whalen C (2019) Refugee and asylum-seeking children: interrupted child development and unfulfilled child rights. Children (Basel) 6(11):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/children6110120 (PMID: 31671545; PMCID: PMC6915556)

Rights to access healthcare for migrant and/or undocumented children [Internet] (2021) RCPCH. Available from: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/right-access-healthcare

World Health Organization. Determinants of health [Internet] (2022) Who.int. Available from: https://www.who.int

CDC. Diseases & Conditions [Internet] (2018) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diseasesconditions/index.html

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dr. Jaya Chawla and Dr. Nour Houbby and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Piet Leroy

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chawla, J., Houbby, N., Boutros, S. et al. Emergency paediatric medicine consultation—a practical guide to a consultation with refugee and asylum-seeking children within the paediatric emergency department. Eur J Pediatr 182, 4379–4387 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05067-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05067-0