Abstract

To analyze the efficacy of using honey to treat acute cough in children. Systematic review, synthesis without meta-analysis. We searched PubMed, Scopus, CENTRAL, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases on August 15, 2022, for words honey and cough. Randomized controlled trials conducted in children were included. Risk-of-bias and evidence quality were assessed. Studies were not pooled due to lack of key information. Instead, we provided the range of observed effects for the main outcomes. Three hundred ninety-six papers were screened, and 10 studies were included. Two studies had high risk-of-bias and six had some concerns. Honey seemed to decrease cough frequency more than placebo/no treatment (range of observed effect 0.0–1.1 points) and cough medication (0.2–0.9 points). Sleep improved more often in the honey group (range of effect was 0.0–1.1) compared to placebo/no treatment and (− 0.2–1.1 points) compared to cough medication. Quality of the evidence was low to very low.

Conclusion: We found low quality evidence that honey may be more effective than cough medication or placebo/no treatment in relieving symptoms and improving sleep in children with acute cough. Better quality randomized, placebo-controlled blinded trials are needed to confirm the effectiveness of honey in treating acute cough in children.

Trial registration: CRD42022369577.

What is Known: • Honey has been suggested to be effective as a symptomatic treatment in acute cough. • Prior randomized trials have had conflicting results and thus an overview of the literature was warranted. | |

What is New: • Based on low quality evidence honey may be more effective than placebo or over-the-counter medications for acute symptom reliwef in cough. • Future studies with better reporting are needed to confirm the results. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cough is among the most common symptoms in children and the majority of children have at least one episode of acute cough annually [1, 2]. Acute cough is typically classified as cough lasting less than 4 weeks [3]. Acute respiratory tract infection is the most common cause of cough in children [2]. Cough affects the quality of life of both the child and his/her parents; thus, effective treatments are needed [4]. Cough medicines and syrups have not been effective in children and have also been associated with severe harm [5]. Therefore, nowadays the use of cough medication is not recommended and many guidelines prohibit the use of such products in children [6, 7].

The World Health Organization and many treatment guidelines have proposed or endorsed the use of honey to treat acute cough [8,9,10]. Honey has been examined in several randomized controlled trials, but the results varied. The latest systematic reviews published in 2018 and 2021 stated that honey is an effective treatment for cough and causes no severe harm; therefore, it could be used to treat acute cough [11, 12]. The latest systematic review in 2021 included both adults and children and concluded that honey is an effective alternative to antibiotics in the treatment of acute cough, even though honey’s efficacy was not compared to antibiotics [12]. Furthermore, several novel studies on honey and acute cough have been conducted after the 2018 Cochrane review, which focused on children. Therefore, we decided to update the evidence regarding the role of honey in the symptomatic treatment of acute cough in children.

Methods

Search strategy

PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Web of Science databases were searched on August 15, 2022. The following keywords were used: honey and cough. We only included studies published in English. We did not use any filters in the search. The search results were uploaded to Covidence software (Covidence, Melbourne, Australia) for the screening process.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Only randomized controlled trials were included regardless of blinding. The study intervention had to be honey or a combination product that included honey. The comparator intervention could be placebo, no treatment, or cough medication. We included studies conducted in children ranging in age between 1 and 18 years. Animal studies were excluded. Observational studies and all other studies not presenting original data were excluded.

Review process

Two authors (IK and MR) individually screened the abstracts and full texts. Conflicts were resolved by mutual decision. Outcome data were then extracted into an Excel spreadsheet. We used the Cochrane risk-of-bias 2.0 tool to assess the risk-of-bias in the included studies [13]. Risk-of-bias figures were generated with the robvis package in R version 4.0.3. Evidence quality was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation, (GRADE) methodology [14].

Outcome measures

Our main outcomes of interest were change in the cough frequency, cough severity, and children’s sleep quality after onset of the medication. Our secondary outcome was the rate of adverse events.

Statistics

Data analyses were performed according to the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Review Guidelines, and Review Manager software version 5.4 was used for the analyses. Originally, our plan was to either calculate the mean differences or the standardized mean differences for the main outcomes and present forest plots and funnel plots. We hypothesized that the included studies would have different dosing in the interventions and heterogenous comparator groups; thus, we decided to use a random-effects model. However, during the data extraction process, we noticed that the reporting of the main outcomes was limited, and typically standard deviations (SDs) were missing usually both for the change from baseline values and the post-intervention values. We decided not to input data using SDs from similar studies, although it would be allowed by the Cochrane handbook. As the SDs were missing in most of the studies and outcomes, most of the results would have been based on input values instead of true observed values. Thus, we utilized alternative methods to produce a systematic review of evidence without a meta-analysis and we decided to present the range of the observed effects for each outcome in tables. Thus, we presented the difference between the intervention and the comparator group as a change from baseline and the likely overall direction of this difference. Due to the lack of SD reporting in the original studies, we were unable to calculate any uncertainty estimates.

We reported our systematic review and meta-analysis findings according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and we provided the PRISMA statement in a supplementary file (Supplement 1) [15]. Because we did not perform a quantitative analysis, we also utilized the Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) guideline [16].

Protocol registration

We registered our protocol in Prospero, registration number: CRD42022369577.

Results

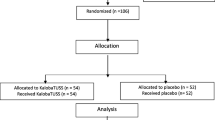

Our search retrieved 396 results; after screening the titles and abstracts, 22 studies were further assessed. Ultimately, 10 of those studies were included in this review [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], as seen in Fig. 1. Of the 10 included studies, five were double-blinded, two were single-blinded, and three were unblinded (Supplementary Table 1). Studies were conducted on every continent except South America. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were relatively similar in all the studies. Pure honey was the intervention in seven of the studies and three studies used products that contained honey. Funding information was reported by seven of the studies; of these studies, three reported no specific funding. One of the included studies was funded by a national honey association. The authors did not report potential conflicts of interests in two studies. Two studies reported that the authors had a relationship with companies that provided the study medication (Supplementary Table 1).

The number of participants in the included studies ranged from 68 to 270 (Table 2). The mean age of the children ranged from 2.4 to 5.4 years. Overall, the cough severity scores at baseline were comparable between the intervention and study groups (Table 1).

Risk-of-bias

Overall risk-of-bias was assessed to be high in three studies, with some concerns of risk-of-bias in six studies and a low concern in two studies (Fig. 2a). Most of the issues were detected in the bias arising from the randomization process and bias due to deviations from the intended interventions (Fig. 2b).

Cough frequency

Ten studies measured cough frequency. Seven studies compared cough frequency between honey and placebo/no treatment and five studies compared cough frequency between honey and cough medication. The observed range of change from baseline favored treatment with honey over placebo/no treatment (0.0 to 1.1 points) and cough medication (0.2 to 0.9 points). The quality of the evidence was ranked as low (Table 2).

Cough severity

Seven studies measured cough severity. Five studies compared honey to placebo/no treatment, and the observed range of effect for the change from baseline was 0.1 to 1.2 points higher in the honey group. Five studies compared honey to cough medication, and the observed range of change from baseline was 0.2 to 1.3 points higher in the honey group. The quality of the evidence was ranked low in both comparisons (Table 2).

Quality of a child’s sleep

Ten studies measured the quality of a child’s sleep. The observed range of effect, as measured by the change from baseline, was 0.0 to 1.1 points higher in the honey group in comparison to the placebo/no treatment group and −0.2 to 1.1 points higher in the honey group in comparison to the cough medication group (low quality evidence; Table 2).

Adverse events

Seven studies measured adverse events. In the honey group, the reported percentage of children with an adverse effect ranged from 0.0 to 14.3%. Adverse events mostly included nausea and vomiting. In the placebo/no treatment group, the percentage of children with an adverse effect ranged from 0.0 to 1.4%; in the cough medication group, it ranged from 0.0 to 3.0%. Additionally, one study stated that there were no differences in the rate of adverse effects in honey or cough medicine groups, but it did not report specific results. The quality of the evidence was ranked as very low (Table 2).

Discussion

Honey seems to be more effective than a placebo/no treatment or cough medications in relieving symptoms of acute cough in children. Overall, the quality of the evidence was low and meta-analysis was not possible due to heterogeneous reporting and the lack of key information in the included studies. Therefore, a combined statistical estimate could not be produced.

Our results are in line with previous meta-analyses. The Cochrane review from 2018 stated that honey could be effective in children in comparison to placebo/no treatment and most types of cough medication [11]. Compared to this previous review, we were able to include four additional studies. Of the additional studies, one double-blinded placebo-controlled study showed a clear null effect [23]. Although we did not perform meta-analysis, the systematic review of the range of observed effects indicated indirectly that honey would be more effective than placebo/no treatment and cough medication.

Interestingly, the most recent meta-analysis, which included adults, stated that honey could be an alternative to antibiotics, but we were unable to find a single study in which antibiotics would have been the comparator group [12]. The conclusion that can be made based on their analysis and the current report is that honey may be effective in reducing symptoms in children suffering from acute cough. Unfortunately, the quality of the reporting of adverse effects was low. It seems that honey may have a higher possibility of causing adverse events than placebo/no treatment. Based on our results, no sufficient comparison between honey and cough medication can be made. However, this is not a limitation as, generally, the use of cough medications should be avoided in children.

Most of the included studies reported the outcome as a change from the baseline assessed using a Likert scale (varying from 5 to 7 point scale). The observed differences in the change from baseline ranged between 0.0 and 1.2 points in these scales. Unfortunately, none of the included studies discussed the minimal important clinical difference [27]. Furthermore, all of the studies utilized a parent-reported outcome measurement; none of the studies aimed to analyze objective outcomes, such as cough frequency, measured by recording sounds while a child was sleeping. It is interesting to note that, in the included studies the patients in the placebo/no treatment group showed improvement, which indicates that usually a cough will spontaneously resolve in children.

Based on our results, it seems feasible to tell the parents that honey is a possible and likely effective treatment for acute cough but it may cause some adverse reactions (mainly vomiting or nausea). Future randomized studies with a double-blinded, placebo-controlled design are needed to determine the effectiveness of honey and the rate of adverse events before it is possible to make stronger recommendations for clinical practice.

Protocol deviations

In comparison to the original protocol, we decided not to synthesize the results as a meta-analysis due to the high heterogeneity in the given interventions and comparator groups and due to lack of vital information for the pooling of the results, as nearly all of the included studies lacked SDs for the selected outcomes. Therefore, the results of such a pooled meta-analysis would be vague and have a high risk of bias. Instead, we decided to analyze the range of observed effects as doing so only requires evaluating the effect of estimate measures. However, this decision was made after publication of the protocol, which can be seen as a clear protocol deviation.

Strengths and limitations

We decided to conduct our systematic review according to the original protocol regarding the study question and outcome assessment, which can be seen as a strength of this review. Furthermore, we did not forcefully conduct a meta-analysis based on input variables. However, a limitation of this review is that we deviated from the intended protocol by changing our statistical analysis plan. The main limitation to the interpretation of the results was the poor reporting on and coverage of adverse events. Due to limited reporting of uncertainty estimates in the original studies (missing standard deviations, interquartile ranges, CI, p-values), we were unable to provide uncertainty estimates for our range of observed effect estimate. This makes the results harder to interpret.

Conclusion

This review presents low quality evidence that honey may be more effective than cough medication or placebo/no treatment in relieving symptoms and improving sleep in a child with acute cough. However, only two studies had low risk of bias, and one showed benefit while the other did not show evidence of benefit. Thus, further randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded trials are needed to confirm the efficacy and improve the quality of evidence regarding the use of honey to treat acute cough in children.

Data availability

All data extracted during the review process are available in the manuscript and supplement.

References

Bergmann M, Haasenritter J, Beidatsch D, Schwarm S, Hörner K, Bösner S et al (2021) Coughing children in family practice and primary care: a systematic review of prevalence, aetiology and prognosis. BMC Pediatr 21(1):260

Bergmann M, Haasenritter J, Beidatsch D, Schwarm S, Hörner K, Bösner S et al (2021) Prevalence, aetiologies and prognosis of the symptom cough in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract 22(1):151

Morice AH, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K, Birring SS, Dicpinigaitis P, Domingo Ribas C et al (2020) ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur Respir J 55(1):1901136

Anderson-James S, Newcombe PA, Marchant JM, Turner CT, Chang AB (2021) Children’s acute cough-specific quality of life: revalidation and development of a short form. Lung 199(5):527–534

Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T (2014) Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (11):CD001831

Tapiainen T, Aittoniemi J, Immonen J, Jylkkä H, Meinander T, Nuolivirta K et al (2016) Finnish guidelines for the treatment of laryngitis, wheezing bronchitis and bronchiolitis in children. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992 105(1):44–9

Palmu S, Heikkilä P, Kivistö JE, Poutanen R, Korppi M, Renko M et al (2022) Cough medicine prescriptions for children were significantly reduced by a systematic intervention that reinforced national recommendations. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992 111(6):1248–9

Malesker MA, Callahan-Lyon P, Ireland B, Irwin RS, Adams TM, Altman KW et al (2017) Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment for acute cough associated with the common cold: CHEST expert panel report. Chest 152(5):1021–1037

Marseglia GL, Manti S, Chiappini E, Brambilla I, Caffarelli C, Calvani M et al (2021) Acute cough in children and adolescents: a systematic review and a practical algorithm by the Italian Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 49(2):155–169

World Health Organization (2001) Cough and cold remedies for the treatment of acute respiratory infections in young children [Internet]. World Health Organization [cited 2022 Oct 22]. Report No.: WHO/FCH/CAH/01.02. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66856

Oduwole O, Udoh EE, Oyo-Ita A, Meremikwu MM (2018) Honey for acute cough in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD007094

Abuelgasim H, Albury C, Lee J (2021) Effectiveness of honey for symptomatic relief in upper respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Evid-Based Med 26(2):57–64

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I et al (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 28(366):l4898

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J et al (2011) GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 64(4):383–94

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 29(372):n71

Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S et al (2020) Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ 16:l6890

Ayazi P, Mahyar A, Yousef-Zanjani M, Allami A, Esmailzadehha N, Beyhaghi T (2017) Comparison of the effect of two kinds of Iranian honey and diphenhydramine on nocturnal cough and the sleep quality in coughing children and their parents. PLoS ONE 12(1):e0170277

Canciani M, Murgia V, Caimmi D, Anapurapu S, Licari A, Marseglia G (2014) Efficacy of Grintuss (R) pediatric syrup in treating cough in children: a randomized, multicenter, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ital J Pediatr 40

Carnevali I, La Paglia R, Pauletto L, Raso F, Testa M, Mannucci C et al (2021) Efficacy and safety of the syrup “KalobaTUSS (R)” as a treatment for cough in children: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. BMC Pediatr 21(1)

Cohen HA, Rozen J, Kristal H, Laks Y, Berkovitch M, Uziel Y et al (2012) Effect of honey on nocturnal cough and sleep quality: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Pediatrics 130(3):465–471

Cohen HA, Hoshen M, Gur S, Bahir A, Laks Y, Blau H (2017) Efficacy and tolerability of a polysaccharide-resin-honey based cough syrup as compared to carbocysteine syrup for children with colds: a randomized, single-blinded, multicenter study. World J Pediatr 13(1):27–33

Miceli Sopo S, Greco M, Monaco S, Varrasi G, Di Lorenzo G, Simeone G (2015) Effect of multiple honey doses on non-specific acute cough in children. An open randomised study and literature review. Allergol Immunopathol Madr 43(5):449–55

Nishimura T, Muta H, Hosaka T, Ueda M, Kishida K (2022) Multicentre, randomised study found that honey had no pharmacological effect on nocturnal coughs and sleep quality at 1–5 years of age. Acta Paediatr

Paul IM, Beiler J, McMonagle A, Shaffer ML, Duda L, Berlin CM Jr (2007) Effect of honey, dextromethorphan, and no treatment on nocturnal cough and sleep quality for coughing children and their parents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161(12):1140–1146

Shadkam MN, Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Mozayan MR (2010) A comparison of the effect of honey, dextromethorphan, and diphenhydramine on nightly cough and sleep quality in children and their parents. J Altern Complement Med 16(7):787–793

Waris A, Macharia M, Njeru EK, Essajee F (2014) Randomised double blind study to compare effectiveness of honey, salbutamol and placebo in treatment of cough in children with common cold. East Afr Med J 91(2):50–56

Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH (1989) Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials 10(4):407–15

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Eastern Finland (UEF) including Kuopio University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Two authors performed the work nearly equally. IK was in charge of statistics and wrote the initial draft. MR revised and commented it critically.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Tobias Tenenbaum

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuitunen, I., Renko, M. Honey for acute cough in children — a systematic review. Eur J Pediatr 182, 3949–3956 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05066-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05066-1