Abstract

A significant increase in pornography use has been reported in the adolescent population worldwide over the past few years, with intensification of the phenomenon during the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of the present review is to provide data on the frequency of pornography consumption among adolescents during the pandemic and raise awareness about its potential impact on personal beliefs and sexual attitudes in the long term. A comprehensive literature review was performed in two scientific databases using the crossmatch of the terms “pornography”, “adolescents” and “COVID-19”. A significant increase in pornography consumption in adolescents was documented during the COVID-19 pandemic as a result of social detachment. Fulfilment of sexual desires in the context of social distancing, alleviation of COVID-19-related boredom and psychological strain, and coping with negative emotions are some of the reported reasons for increased pornography use during the pandemic. However, concerns have been raised in the literature regarding potentially negative effects of excessive pornography use from an early age, including the development of pornography addiction, sexual dissatisfaction and aggressive sexual attitudes reinforced by gender preoccupations and sexual inequality beliefs.

Conclusion: The extent to which increased pornography consumption from an early age during the COVID-19 pandemic may have affected adolescents’ mental well-being, personality construction and sexual behaviour is yet to be seen. Vigilance from the society as a whole is required so that potential negative adverse effects of adolescent pornography use and potential social implications are recognized early and managed. Further research is needed so that the full impact of the COVID-19-related pornography use in the adolescent population is revealed.

What is Known: •A significant increase in pornography consumption has been documented in the adolescent population worldwide over the past decades due to its quick, affordable and easy access from electronic devices and the possibility of anonymous and private participation. •During the COVID-19 pandemic, this phenomenon was intensified as a coping mechanism to social isolation and increased psychosocial strain. | |

What is New: •Concerns have been raised regarding the risk of pornography addiction in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic, making the post-pandemic adaptation challenging. •Awareness is raised in parents, health care providers and policy makers about the potential negative impacts of pornography consumption from an early, vulnerable age, such as sexual dissatisfaction and development of aggressive sexual attitudes and sex inequality beliefs. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past decades, western societies have experienced a revolution in internet communication technology and massive access to online information from an early age. Since internet access became widely accessible, it is well known that a significant percentage of the adolescent population lives digital lives and that internet represents a central feature of their identity. Among the information consumed through digital media, online pornographic material is also included [1].

Indeed, it has been widely described that pornography use is on the rise in adolescents [2], which requires attention as this is a critical period of sexual development [3,4,5,6,7]. Availability of mobile internet from earlier ages has removed previous barriers to accessing pornography and is synchronous to the social acceptability of pornography use [2].

During the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, this phenomenon became more intense as a result of social detachment. An unprecedented increase in pornography consumption was documented worldwide both in adults and in adolescents [8,9,10,11,12,13], also confirmed by a surge in traffic on pornographic websites reported after the outbreak of the pandemic [14, 15]. The physical distancing policies that were imposed in order to minimize the risk of transmission of the virus translated into social isolation and increased psychosocial strain worldwide. These measures are believed to have changed social, interpersonal and potentially sexual relationships in adults [16]. It has been proposed that high-frequency pornography consumption may require clinical attention due to potential psychological and physical negative outcomes in adults [17]. Little is known about how the pandemic has affected adolescents’ sexual life. Studies are scarce and limited; however, concerns have been raised in the literature regarding potential harms of the pandemic-related pornography consumption on adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, but also on their sexual beliefs and attitudes in the long term [3, 18, 19].

The aim of the current review is to provide existing data on adolescent pornography use during the COVID-19 pandemic, taking into consideration aspects such as frequency of consumption and the potential impact of this recent phenomenon on adolescent sexual life and behaviour in the long term.

Methods

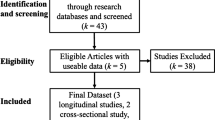

A comprehensive literature research on adolescent pornography use and adolescent pornography use during the COVID-19 pandemic was performed. Data were extracted from two different scientific databases, Medline (PubMed) and Web of Science, to include studies up to 2023. The search terms included “pornography”, “adolescents” and “COVID-19”. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline and checklist was used for the conduction of this review (Fig. 1).

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility of the studies was assessed in two steps. First, the selection of studies was based on the relevancy of titles and abstracts. In the second step, the relevancy of the full texts of the remaining studies was assessed based on the eligibility criteria of the present study.

The inclusion criteria for the articles selected were as follows: (a) being published in peer-reviewed journals; (b) referring to pornography use during the COVID-19 pandemic, (c) being published after 2020, (d) referring to adolescents < 18 years old, (e) being written in English. Exclusion criteria were applied for (a) abstracts or conference abstracts without published full text and (b) articles written in other than the English language.

Data extraction

The information extracted from full texts of the selected articles included the first author name, country of study, year of publication, study design, sample characteristics, existing knowledge on pornography use in adolescents and the possible role of the COVID-19 pandemic on pornography use in adolescents.

Selection process

A total of 26 articles were collected during the initial search. After duplicate removal, 7 publications were excluded. After the eligibility criteria were applied, and based on the relevancy of the title and the abstract and following the full-text screening, 11 articles were finally included (Table 1).

Results

Motivations for pornography use

Seeking for sexual pleasure is the most common reason for pornography use in adults and adolescents [4, 20]. Due to its accessible, affordable and anonymous nature, pornography consumption enables the fulfilment of sexual desires particularly when the possibility of casual sex is limited, as in the presence of social distancing requirements [21]. Indeed, during the restrictive and containment measures imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, pornography use and autoerotism became channels through which sexuality was expressed. This unprecedented consumption of online pornography during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic era was not only fuelled by social isolation, but hypothetically, also caused by it [15]. Alternatively, the increased time spent at home during the lockdowns was associated with increased engagement in internet use and screen-based activities, including pornography use [22,23,24].

Although not all studies have demonstrated that social distancing during the pandemic resulted in less sexual interaction among adults [25], a significant number of studies from different countries have shown a decrease in partnered sex and increased online dating during the pandemic [26,27,28,29]. Similar results were demonstrated in studies on adolescents and young adults, who turned to digital forms of communication with partners and to digital pornography use during the pandemic [23, 30, 31].

Other reasons of pornography use include sexual curiosity, self-exploration and the need for stress reduction, alleviation of boredom and coping with negative emotions. In this regard, pornography use in adults has been described as a “constructive coping behaviour” to overcome “boredom and fear” caused by the pandemic, also known as “eroticization of fear” [32]. In contrast, for some authors, increased pornography use could represent a maladaptive coping strategy and dysfunctional behaviour toward stressors, such as loneliness, fear and feeling of powerlessness triggered by situations such as the pandemic [33, 34]. Previous studies have shown that adolescents, who seem to have suffered greatly from psychological consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic, use pornography to cope with negative feelings [35, 36].

Another particularly interesting approach of pornography use is that of “escapism”. It has been proposed that online pornography offers the individual the possibility to escape from the real world and participate in an artificial and more perfect sexual situation, with an “ideal self”. This can be liberating for individuals suffering from social anxiety or body image issues, as sexual reward can be achieved in privacy and through body image avoidance [37, 38].

Frequency

Increased frequency of pornography use in male and female adolescents has been documented worldwide, partly due to peer influence and the need for autonomy. According to large-scale, nationally representative data from the USA, Canada and Europe, 63–68% of adolescents reported lifetime pornography use [39, 40]. Although girls and women consume online pornography, boys and men consume pornography at higher rates [13, 18, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. In a study by Bőthe et al., boys reported not only more frequent pornography use, but also higher levels of problematic pornography use than girls. However, the majority of adolescents engaging in pornography use reported no negative impact on their life or distress [48].

In addition to the increasing frequency of pornography use, the age of first pornography use seems to also be declining [2, 41]. Interestingly, little parental supervision and dysfunctional or weak family relations have been associated with increased pornography use during adolescence [6].

Concerns regarding pornography use in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic

-

(i)

Addiction

The increasing rates of pornography use among adolescents over the past few years, showing a surge during the COVID-19 pandemic, have raised concerns with regard to the development of addiction due to the vulnerability of the adolescent developing brain [49]. According to a longitudinal study on internet addiction, among the internet-related activities, online pornography was the most likely to be addictive [50]. “Internet pornography addiction” or “problematic online pornography use”, an under-researched phenomenon, is placed under the umbrella construct of hypersexual or “compulsive sexual behaviour”. Rousseau et al. have demonstrated a positive association of depressive and anxiety symptoms with problematic pornography use in adolescents in a recent longitudinal study [51]. Problematic pornography use has been identified in 5–14% of adolescents [52, 53].

In adults, it has been proposed that problematic internet use may be the result of the combination between an underlying vulnerability with a stress factor, such as the COVID-19 pandemic [54,55,56]. Also, that internet addiction could in the long term have a negative impact on psychosocial and physical well-being [57].

Addictive behaviours, such as internet gaming or pornography, have been associated with dysfunctions in dopaminergic circuits that feed reward mechanisms [58]. In a study published in 1951, it was reported that a greater activation of the brain’s reward systems occurs by an artificial stimulus compared to a natural stimulus of a similar type [59]. In 2010, Barrett described internet pornography as an example of supranormal stimulus, due to the numerous artificial scenarios available to the consumer to choose from, seeking for new, more perfect content, thus greater reward, entering the “addictive mode” [60]. Also, similarities have been found in brain dysfunction between substance and pornography addiction [61].

In the pandemic context, adoption of a particular lifestyle for elongated periods can make post-pandemic “re-adaptation” difficult and engagement in physical sexual activity dysfunctional [62].

-

(ii)

Sexual dissatisfaction/frustration

Pornography may affect different aspects of sexual life, including sexual satisfaction [63]. Long-term pornography use is associated with disappointment and reduced sexual satisfaction due to the supranormal nature of pornography and unrealistic expectations of sexual performance in real life [64], although it is not considered a major risk factor of sexual dysfunction [65]. Adolescents may perceive pornography as real due to lack of real-life experiences [27]. As a result, personal insecurities about adolescents’ bodies, physical appearance and sexual performance may develop [66]. A recent expression of pornography-related frustration regarding body image dissatisfaction involves decisions concerning genital cosmetic surgery in females have been associated with pornography use and, specifically, with negative genital self-image despite the genitalia being in a normal range or with negative comments from sexual partners [67,68,69].

In addition, it has been suggested that the distance between reality and fantasy may cause reduction in desire and interest in sex [70]. More importantly, pornography use has been associated with impaired mental well-being reflected by lower self-esteem, life satisfaction and increased depression symptoms among adolescents [6]. This is particularly worrying considering the elevated stress levels and increased mental health issues reported during the pandemic in children and adolescents [71, 72]. However, a causal relationship between pornography and mental well-being constructs has not been established with certainty [73].

Furthermore, excessive pornography consumption may affect the quality of intimate relationships [74]. Specifically, it has been inversely associated with relationship satisfaction and closeness and positively associated with depression and loneliness, which may also explain the documented increase in pornography use during the pandemic. Although solitary sexual desire may be satisfied through fake virtual relationships, the need for affection, intimate relationships and dyadic sexual desire cannot be fulfilled by this means [8].

-

(iii)

Shaping of aggressive and sex inequality attitudes

The possible impact on adolescents’ sexual attitude and belief system constitutes one of the most worrying aspects of pornography use during this vulnerable age. Children and adolescents are considered the most vulnerable audiences to sexually explicit material [5]. Due to reduced control over impulses, adolescents have the propensity to mimic sexual behaviours and their sexual attitude is more likely to be defined by pornographic scenes they have viewed. The more frequently someone consumes pornography, the more the person’s sexual behaviour is guided by the viewed scenes [75, 76]. Such scenes often include aggressiveness and images of abuse favouring gender stereotypes and gender-inequality beliefs [3, 6, 62, 75, 77]. As a result, expectations about what behaviours partners should engage in are developed and reinforced [2, 42].

Worryingly, several studies have reported significant relationship between online pornography consumption and attitudes supportive of violence and tolerance of sexual violence toward women [42, 43, 62, 78, 79]. A study that examined 172 online pornography videos demonstrated that male performers caused intentional harm and pain in female performers, whereas 58% of the videos showed non-consensual sexual interactions [21]. Another study showed that exposure to online pornography at an early age is associated with increased risk of juvenile sexual perpetration [21, 44, 47, 63]. Furthermore, according to an anonymous survey among 4564 teenagers aged 14–17 years old, male teenagers who were frequent consumers of online pornography were more likely to admit sexual coercion or using force to obtain sexual intercourse [44]. Exposure to sexual images of pleasure on sexually violent acts, where women’s consent is not necessary, or of male domination over females and tolerance by female performers who react positively to humiliation and violence, may promote a culture of tolerance to sexual behaviours that reinforce sexual inequality and non-consensual intercourse [80, 81].

In the same context, criticism has been raised regarding the objectification of women, who are transformed into sexual artifacts and dehumanized to the point where their role is to provide sexual pleasure to men [82]. Girls report being pressured by their boyfriends into watching pornography and re-enacting pornographic scenes watched [83]. They also might get confused about what their role is in a sexual relationship, and may engage in behaviours that they are not comfortable with or that are against their will, either because they are forced by their partners or because they perceive that they have the obligation to do so.

In addition, adolescents have limited ability to differentiate between what is”normal” and “not normal” sexual behaviour, thus pornography consumption is thought to encourage eccentric practices and social norm rule breaking [6]. Frequent consumers may potentially become desensitized to sexual behaviours that have previously been believed to be unusual [42].

Miseducation

Another aspect to be considered is the replacement of the conventional ways of sexual education by pornography use. Learning about sex through distorted versions of masculinity and sexual behaviour, in an uncontrolled and non-scientific context, may influence sexual beliefs and have a negative impact on adolescents’ sexuality [66, 70, 84,85,86].

Conclusion

Pornography consumption in adults and adolescents has risen to a worldwide proportion due to quick and easy access from electronic devices and the possibility of anonymous and private participation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this phenomenon became more intense due to its association with physical contact [87, 88]. In addition, the psychosocial burden imposed by the pandemic, the emergence or deterioration of mental health issues in the adolescent population and the risk of addictions further contributed to the intensification of pornography use as a coping mechanism, making post-pandemic “re-adaption” challenging [11, 71, 89].

The current review summarizes viewpoints on the possible impact of pornography use during the COVID-19 pandemic on sexual life of adolescents, a meaningful aspect of health development. It highlights potential immediate and long-term future adverse effects of pornography addiction in this population, an underestimated contemporary issue that requires attention. Questions arise as to what the role of pornography use is in the development of personal preoccupations and attitudes that might determine future sexual behaviour and intimate relationships, the construction of personality, and the perception of equality between the sexes. Also, concerns about what the appropriate lower age, if any, for pornography use is, so that negative personal and social implications are prevented.

The presented data bring to surface concerns regarding the absence of sex education before and after the pandemic in many parts of the world. This, in association with insufficient parental supervision and reluctance to engage children and adolescents in discussions about their sexual life or pornography consumption, results in learning for sex through inappropriate sources. Thus, the present work aims to raise awareness regarding potential negative impacts of pornography use and the need for prevention education and early intervention, particularly during and after emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Parents should be made aware of the importance of their involvement so that potential harms of uncontrolled pornography use, such as its addictive potential during adolescence and the possibility of development of gender stereotypes, are prevented [2, 41, 90].

Furthermore, prevention efforts, including educational programs, need to be implemented in the school and other settings to educate where porn misinforms. Sexual education strategies should be directed toward helping children have more safe and positive online experiences and lead respectful, coercion-free sexual relationships. Health care professionals also need to be educated on diagnostic tools for detecting problematic pornography use and on appropriate intervention methods [1, 2, 47, 91].

It becomes apparent that cooperation between all parts involved, including parents, schools, health care providers, social services and policy makers, is of major importance. Against influences favouring aggression, sex inequality, misogynistic, offending and humiliating behaviours, vigilance from society as a whole is warranted and implementation of education strategies with an emphasis to moral values and principles based on equality and respect.

Would it be an exaggeration to assume that excessive pornography consumption from an early age is a risk factor for problematic sexual behaviour and a step backwards to the victory of equality? Have we considered all the secondary impacts of COVID-19, including the full impact of the pandemic on adolescents’ sexuality? As this is an understudied field, further studies are needed before safe conclusions are drawn.

Data Availability

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Corona virus disease-19

References

de Alarcón R, de la Iglesia JI, Casado NM, Montejo AL (2019) Online porn addiction: what we know and what we don’t—a systematic review. J Clin Med 8:91. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8010091

Mead D, Sharpe M (2020) Aligning the “Manifesto for a European research network into problematic usage of the Internet” with the diverse needs of the professional and consumer communities affected by problematic usage of pornography. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:13462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103462

Waterman EA, Wesche R, Morris G, Edwards KM, Banyard VL (2022) Prospective associations between pornography viewing and sexual aggression among adolescents. J Res Adolesc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12745. Online ahead of print

Bőthe B, Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Bergeron S, Demetrovics Z (2019) Problematic and non-problematic pornography use among LGBTQ adolescents: a systematic literature review. Curr Addict Rep 6:478–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00289-5

Owens EW, Behun RJ, Manning JC, Reid RC (2012) The impact of internet pornography on adolescents: a review of the research. Sex Addict Compuls 19:99–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2012.660431

Peter J, Valkenburg PM (2016) Adolescents and pornography: a review of 20 years of research. J Sex Res 53:509–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1143441

Price J, Patterson R, Regnerus M, Walley J (2016) How much more XXX is generation X consuming? Evidence of changing attitudes and behaviors related to pornography since 1973. J Sex Res 53:12–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.1003773

Cocci A, Giunti D, Tonioni C, Cacciamani G, Tellini R, Polloni G et al (2020) Love at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic: preliminary results of an online survey conducted during the quarantine in Italy. Int J Impot Res 32:556–557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-020-0305-x

Shilo G, Mor Z (2020) COVID-19 and the changes in the sexual behavior of men who have sex with men: results of an online survey. J Sex Med 17:1827–1834. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1143441

Lau WKW, Ngan LHM, Chan RCH, Wu WKK, Lau BWM (2021) Impact of COVID-19 on pornography use: evidence from big data analyses. PLoS ONE 16:e0260386. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260386

Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM (2020) Physically isolated but socially connected: psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can J Behav Sci 52:177–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000215

Awan HA, Aamir A, Diwan MN, Ullah I, Pereira-Sanchez V, Ramalho R, Orsolini L, de Filippis R, Ojeahere MI, Ransing R, Vadsaria AK, Virani S (2021) Internet and pornography use during the COVID-19 pandemic: presumed impact and what can be done. Front Psychiatry 12:623508. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.623508

Grubbs JB, Perry SL, Weinandy JTG, Kraus SW (2022) Porndemic? A longitudinal study of pornography use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in a nationally representative sample of Americans. Arch Sex Behav 51:123–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02077-7

Pornhub Insights (2020, May 26) Coronavirus update – May 26. Retrieved from https://www.pornhub.com/insights/coronavirus-update-may-26

Mestre-Bach G, Blycker GR, Potenza MN (2020) Pornography use in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Behav Addict 9:181–183

Maretti C, Privitera S, Arcaniolo D, Cirigliano L, Fabrizi A, Rizzo M et al (2020) COVID-19 pandemic and its implications on sexual life: recommendations from the Italian Society of Andrology. Arch Ital Urol Androl. https://doi.org/10.4081/aiua.2020.2.73

Marchi NC, Fara L, Gross L, Ornell F, Diehl A, Kessler FHP (2021) Problematic consumption of online pornography during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical recommendations. Trends Psychiatry Psychother 43:159–166. https://doi.org/10.47626/2237-6089-2020-0090

Svedin CG, Åkerman I, Priebe G (2011) Frequent users of pornography. A population based epidemiological study of Swedish male adolescents. J Adolesc 34:779–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.04.010

Hilton DL Jr (2013) Pornography addiction – a supranormal stimulus considered in the context of neuroplasticity. Socioaffect Neurosci Psychol 3:20767. https://doi.org/10.3402/snp.v3i0.20767

Grubbs JB, Wright PJ, Braden AL, Wilt JA, Kraus SW (2019) Internet pornography use and sexual motivation: a systematic review and integration. Ann Int Commun Assoc 43:117–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2019.1584045

Shor E, Golriz G (2019) Gender, race, and aggression in mainstream pornography. Arch Sex Behav 48:739–751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1304-6

Guessoum SB, Lachal J, Radjack R, Carretier E, Minassian S, Benoit L, Moro MR (2020) Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Res 291:113264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113264

Nelson KM, Gordon AR, John SA, Stout CD, Macapagal K (2020) “Physical sex is over for now”: impact of COVID-19 on the well-being and sexual health of adolescent sexual minority males in the U.S. J Adolesc Health 67:756–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.027

Munasinghe S, Sperandei S, Freebairn L, Conroy E, Jani H, Marjanovic S, Page A (2020) The impact of physical distancing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic on health and well-being among Australian adolescents. J Adolesc Health 67:653–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.008

Yarger J, Gutmann-Gonzalez A, Han S, Borgen N, Decker MJ (2021) Young people’s romantic relationships and sexual activity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 21:1780. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11818-1

Hammoud MA, Maher L, Holt M, Degenhardt L, Jin F, Murphy D et al (2020) Physical distancing due to COVID-19 disrupts sexual behaviors among gay and bisexual men in Australia: implications for trends in HIV and other sexually transmissible infections. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 85:309–315. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000002462

Li W, Li G, Xin C, Wang Y, Yang S (2020) Challenges in the practice of sexual medicine in the time of COVID-19 in China. J Sex Med 17:1225–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.04.380

Suen YT, Chan RCH, Wong EMY (2020) To have or not to have sex? COVID-19 and sexual activity among Chinese-speaking gay and bisexual men in Hong Kong. J Sex Med 18:29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.10.004

Coombe J, Kong FYS, Bittleston H, Williams H, Tomnay J, Vaisey A et al (2020) Love during lockdown: findings from an online survey examining the impact of COVID-19 on the sexual health of people living in Australia. Sex Transm Infect 97:357–362. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2020-054688

Lindberg LD, Bell DL, Kantor LM (2020) The sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 52:75–79. https://doi.org/10.1363/psrh.12151

Firkey MK, Sheinfil AZ, Woolf-King SE (2020) Substance use, sexual behavior, and general well-being of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a brief report. J Am Coll Healh 70:2270–2275. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1869750

Döring N (2020) How is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting our sexualities? An overview of the current media narratives and research hypotheses. Arch Sex Behav 49:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01790-z

Siste K, Hanafi E, Sen LT, Christian H, Adrian, Siswidiani LP et al (2020) The impact of physical distancing and associated factors towards internet addiction among adults in Indonesia during COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide web-based study. Front Psychiatry 11:580977. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.580977

Nebot-Garcia JE, Ruiz-Palomino E, Giménez-García C, Gil-Llario MD, Ballester-Arnal R (2020) Sexual frequency of Spanish adolescents during confinement by COVID-19. Rev Psicol Clin Con Ninos Adolesc 7:16–26. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2020.mon.2038

Stavridou A, Stergiopoulou AA, PanagouliE MG, Thirios A et al (2020) Psychosocial consequences of COVID-19 in children, adolescents and young adults: a systematic review. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 74:615–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13134

Wéry A, Billieux J (2016) Online sexual activities: an exploratory study of problematic and non-problematic usage patterns in a sample of men. Comput Hum Behav 56:257–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.046

Rodgers RF, Melioli T, Laconi S, Bui E, Chabrol H (2013) Internet addiction symptoms, disordered eating, and body image avoidance. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 16:56–60. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.1570

Li D, Liau A, Khoo A (2011) Examining the influence of actual-ideal self-discrepancies, depression, and escapism, on pathological gaming among massively multiplayer online adolescent gamers. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 14:535–539. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0463

Bőthe B, Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Girouard A, Štulhofer A, Dion J, Bergeron S (2020) A large-scale comparison of Canadian sexual/gender minority and heterosexual, cisgender adolescents’ pornography use characteristics. J Sex Med 17:1156–1167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.02.009

Lobe B, Livingstone S, Ólafsson K, Vodeb H (2011) Cross-national comparison of risks and safety on the internet: initial analysis from the EU Kids Online survey of European children. EU Kids Online, Deliverable D6. EU Kids Online Network, London, UK

Boniel-Nissim M, Efrati Y, Dolev-Cohen M (2020) Parental mediation regarding children’s pornography exposure: the role of parenting style, protection motivation and gender. J Sex Res 57:42–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1590795

Bridges AJ (2019) Pornography and sexual assault. In: O’Donohue WT, Schewe PA (eds) Handbook of sexual assault and sexual assault prevention. Springer Cham, pp 129–150

Malamuth NM (2018) “Adding fuel to the fire”? Does exposure to non-consenting adult or to child pornography increase risk of sexual aggression? Aggress Violent Behav 41:74–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.02.013

Stanley N, Barter C, Wood M, Aghtaie N, Larkins C, Lanau A, Överlien C (2018) Pornography, sexual coercion and abuse and sexting in young people’s intimate relationships: a European study. J Interpers Violence 33:2919–2944. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516633204

Weber M, Quiring O, Daschmann G (2012) Peers, parents and pornography: exploring adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit material and its developmental correlates. Sex Cult 16:408–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-012-9132-7

Rostad WL, Gittins-Stone D, Huntington C, Rizzo CJ, Pearlman D, Orchowski L (2019) The association between exposure to violent pornography and teen dating violence in grade 10 high school students. Arch Sex Behav 48:2137–2147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1435-4

Ybarra ML, Thompson RE (2018) Predicting the emergence of sexual violence in adolescence. Prev Sci 19:403–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0810-4

Bőthe B, Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Dion J et al (2022) A longitudinal study of adolescents’ pornography use frequency, motivations, and problematic use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Sex Behav 51:139–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02282-4

Petrovic KZ, Peraica T, Kozaric-Kovacic D, Palavra IR (2022) Internet use and internet-based addictive behaviours during coronavirus pandemic. Curr Opin Psychiatry 35:324–331. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000804

Meerkerk GJ, Van Den Eijnden RJ, Garretsen HF (2006) Predicting compulsive internet use: it’s all about sex! Cyberpsychol Behav 9:95–103. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.95

Rousseau A, Bőthe B, Štulhofer A (2021) Theoretical antecedents of male adolescents’ problematic pornography use: a longitudinal assessment. J Sex Res 58:331–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2020.1815637

Štulhofer A, Rousseau A, Shekarchi R (2020) A two-wave assessment of the structure and stability of self-reported problematic pornography use among male Croatian adolescents. Int J Sex Health 32:151–164

Bothe B, Tóth-Király I, Demetrovics Z, Orosz G (2020) The short version of the problematic pornography consumption scale (PPCS-6): a reliable and valid measure in general and treatment-seeking populations. J Sex Res 58:342–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2020.1716205

Davis RA (2001) A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological internet use. Comput Hum Behav 17:187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00041-8

Li J, Yang Z, Qiu H, Wang Y, Jian L, Ji J et al (2020) Anxiety and depression among general population in China at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. World Psychiatry 19:249–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20758

Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S (2020) Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 3:e2019686. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686

Masaeli N, Farhadi H. Prevalence of Internet-based addictive behaviors during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Addict Dis 39(4):468–488

Blum K, Chen AL, Giordano J, Borsten J, Chen TJ, Hauser M et al (2012) The addictive brain: all roads lead to dopamine. J Psychoactive Drugs 44:134–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2012.685407

Tinbergen N (1951) The study of instinct. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Barrett D (2010) Supernormal stimuli: how primal urges overran their evolutionary purpose. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company

Darnai G, Perlaki G, Zsidó AN, Inhóf O, Orsi G, Horváth R et al (2019) Internet addiction and functional brain networks: task-related fMRI study. Sci Rep 9:15777. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52296-1

King DL, Delfabbro PH, Billieux J, Potenza MN (2020) Problematic online gaming and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Behav Addict 9:184–186. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00016

Efrati Y, Amichai-Hamburger Y (2021) Adolescents who solely engage in online sexual experiences are at higher risk for compulsive sexual behavior. Addict Behav 118:106874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106874

Kirby M (2021) Pornography and its impact on the sexual health of men. Trends in Urology & Men’s Health 12:6–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/tre.791

Landripet I, Štulhofer A (2015) Is pornography use associated with sexual difficulties and dysfunctions among younger heterosexual men? J Sex Med 12:1136–1139. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12853

Collins RL, Strasburger VC, Brown JD, Donnerstein E, Lenhart A, Ward LM (2017) Sexual media and childhood well-being and health. Pediatrics 140:162–166. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1758x

Dogan O, Yassa M (2019) Major motivators and sociodemographic features of women undergoing labiaplasty. Aesthet Surg J 39:517–527. https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjy321

Cranney S (2015) Internet pornography use and sexual body image in a Dutch sample. Int J Sex Health 27:316–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2014.999967

Kalaaji A, Dreyer S, Maric I, Schnegg J, Jönsson V (2018) Female cosmetic genital surgery: patient characteristics, motivation, and satisfaction. Aesthet Surg J 39:1455–1466. https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjy309

Pizzol D, Bertoldo A, Foresta C (2016) Adolescents and web porn: a new era of sexuality. Int J Adolesc Med Health 28:169–173. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2015-0003

Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, Huang Y, Miao J, Yang X, Zhu G (2020) An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Affect Disord 275:112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029

Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V (2020) Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3

Kohut T, Stulhofer A (2018) Is pornography use a risk for adolescent well-being? An examination of temporal relationships in two independent panel samples. PLoS ONE 13:e0202048. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202048

Gleason N, Sprankle E (2019) The effects of pornography on sexual minority men’s body image: an experimental study. Psychol Sex Cult 10:301–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2019.1637924

Vera-Gray F, McGlynn C, Kureshi I, Butterby K (2021) Sexual violence as a sexual script in mainstream online pornography. Br J Criminol 61:1243–1260

Sun C, Bridges A, Johnson JA, Ezzell MB (2016) Pornography and the male sexual script: an analysis of consumption and sexual relations. Arch Sex Behav 45:983–994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0391-2

Livingstone S, Smith PK (2014) Annual research review: harms experienced by child users of online and mobile technologies: the nature prevalence and management of sexual and aggressive risks in the digital age. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 55:635–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12197

Foubert JD, Blanchard W, Houston M, Williams RR Jr (2019) Pornography and sexual violence. In: O’Donohue WT, Schewe PA (eds) Handbook of sexual assault and sexual assault prevention. Springer Cham, pp 109–127

Palermo AM, Dadgardoust L, Arroyave SC, Vettor S, Harkins L (2019) Examining the role of pornography and rape supportive cognitions in lone and multiple perpetrator rape proclivity. J Sex Aggress 25:244–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2019.1618506

Powell A, Henry N (2017) Sexual violence in a digital age. Palgrave Macmillan, London, p 317

Rodenhizer KAE, Edwards KM (2019) The impacts of sexual media exposure on adolescent and emerging adults’ dating and sexual violence attitudes and behaviors: a critical review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 20:439–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017717745

Silva R, Teixeira C, Vasconcelos-Raposo J, Bessa M (2016) Sexting: adaptation of sexual behavior to modern technologies. Comput Hum Behav 64:747–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.036

Rothman EF, Kaczmarsky C, Burke N, Jansen E, Baughman A (2015) “Without porn … I wouldn’t know half the things I know now”: a qualitative study of pornography use among a sample of urban, low-income, Black and Hispanic youth. J Sex Res 52:736–746. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.960908

Mercer D, Parkinson D (2014) Video gaming and sexual violence: rethinking forensic nursing in a digital age. J Forensic Nurs 10(1):27–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/jfn.0000000000000017

Maes C, Vandenbosch L (2022) Adolescents’ of sexually explicit internet material over the course of 2019–2020 in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: a three-wave panel study. Arch Sex Behav 51:105–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02122-5

Perissini AL, Spessoto LCF, Facio Junior FN (2020) Does online pornography influence the sexuality of adolescents during COVID-19? Rev Assoc Med Bras 66:564–565. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.66.5.564

UNFPA (2018) International technical guidance on sexuality education—an evidence-informed approach. UNESCO, UN-AIDS, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN Women and WHO: New York, NY, USA

Ott MA, Bernard C, Wilkinson TA, Edmonds BT (2020) Clinician perspectives on ethics and COVID-19: minding the gap in sexual and reproductive health. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 52:145–149. https://doi.org/10.1363/psrh.12156

Racine N, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Korczak DJ, McArthur BA, Madigan S (2020) Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: a rapid review. Psych Res 292:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113307

Guggisberg M, Dobozy E (2020) Educated women as gatekeepers to prevent sexual exploitation of children. In: Jaworski JA (ed) Advances in sociology research, vol 29. Nova Science Publishers, pp 131–149

Kiraly O, Potenza MN, Stein DJ et al (2020) Preventing problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic: concensus guidance. Compr Psychiatry 100:152180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152180

Socías CO, Brage LB, Nevot-caldentey L (2020). FAMILY SUPPORT AGAINST COVID-19. In SciELO Preprints. https://doi.org/10.1590/SciELOPreprints.297

Lukavská K, Burda V, Lukavský J, Slussareff M, Gabrhelík R (2021) School-Based Prevention of Screen-Related Risk Behaviors during the Long-Term Distant Schooling Caused by COVID-19 Outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(16):8561

Scull TM, Dodson CV, Geller JG, Reeder LC, Stump KN (2022) A Media Literacy Education Approach to High School Sexual Health Education: Immediate Effects of Media Aware on Adolescents' Media, Sexual Health, and Communication Outcomes. J Youth Adolesc 51(4):708–723

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Eirini Kostopoulou contributed to the study conception and design, material preparation, data collection and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Eirini Kostopoulou, who also read and approved the final manuscript. Eirini Kostopoulou agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Peter de Winter.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kostopoulou, E. Impact of COVID-19 on adolescent sexual life and attitudes: have we considered all the possible secondary effects of the pandemic?. Eur J Pediatr 182, 2459–2469 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-04878-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-04878-5