Abstract

The placebo response a significant therapeutic improvement after a placebo intervention — can be high in children. The question arises of how optimal advantages of placebo treatment in pediatric clinical care be achieved. In this era of shared-decision making, it is important to be aware of patients’ and parental attitudes. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to assess teenagers’ and parental views on the use of placebo pills in pediatric clinical care. All patients (aged 12–18 years) and parents of children (aged 0–18 years), visiting the pediatric outpatient clinic between March 2020 through December 2020, were invited to participate in this study multicenter survey study. Of 1644 distributed questionnaires: 200/478 (47%) teenagers and 456/1166 (45%) parents filled out the complete survey. More parents were positive towards prescribing placebo medication than teenagers (80% vs. 71%, p = .019), especially when the clinician disclosed the use of a placebo to parents and teenagers, respectively (76% vs. 55%, p = .019). Increasing age of teenagers was positively associated with the willingness for placebo interventions (OR 0.803, 95%CI 0.659–0.979), as was a higher level of parental education (OR 0.706, 95%CI 0.526–0.949).

Conclusion: This study emphasizes the willingness of teenagers and parents to receive placebo medication. Placebo medication becoming more acceptable and integrated into daily care may contribute to a decrease in medication use.

What is Known: • A placebo is a treatment without inherent power to produce any therapeutic effect, but can result in significant therapeutic improvement, the so-called placebo response. • Treatment response rates after placebo interventions in children can be high, ranging from 41 to 46% in pediatric trials. | |

What is New: • Most teenagers (71%) and parents (80%) find it appropriate for healthcare professionals to prescribe placebo medication. • Compared to adult care, pediatrics has a unique feature to disclose placebo treatment to parents while concealing it for the young patient: the majority of teenagers (85%) and parents (91%) agree to disclose placebo treatment to parents exclusively. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Brief report

A placebo is a substance or procedure without inherent power to produce any therapeutic effect [1]. Nevertheless, it can result in significant therapeutic improvement, the so-called placebo response. This response includes both an actual placebo effect as well as other factors, like spontaneous improvements and regression to the mean [2]. The underlying neurobiological mechanism of the actual placebo effect is likely multifactorial, involving a complex interaction between patients’ beliefs and expectations, social and physical environmental perceptions, and conditioning from past experiences [3, 4]. Treatment success rates after placebo interventions in children can be high, with pooled placebo response rates of 41% and 46% in pediatric functional abdominal pain and pediatric migraine trials, respectively [5, 6]. It is therefore not surprising that many physicians would like to prescribe placebo medication in daily practice, especially to patients with chronic pain and functional disorders [7]. The question arises of how optimal advantages of placebo treatment in clinical care be achieved. A physician can openly discuss the use of placebo medication. However, studies have demonstrated varying treatment effects in patients depending on the labeling of the treatment with lower effects when pills were labeled as placebo (so-called open-label placebo) and higher when pills had an uncertain labeling (i.e., active medication or placebo) [8]. On the other hand, withholding information that a placebo is prescribed raises strong ethical concerns. In this era of shared-decision making, it is important to be aware of patients’ and parental attitudes towards open or covered placebo prescriptions. Surprisingly little attention has been paid to this topic in pediatrics. To date, only one study in the USA has investigated parental views on the clinical use of placebo pills for their child [9]. Hence, we wanted to examine the opinion of parents but also of teenagers, since the latter, by law, fully participate in shared decision-making. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to assess teenagers’ and parental views on the use of placebo pills in pediatric clinical care.

The current study was an ancillary study to an original survey on teenagers’ and parental individual needs for side effects information and the influence of nocebo effect education [10]. This multicenter, cross-sectional survey study was conducted in the Netherlands between March 2020 through December 2020 and enrolled 226 teenagers aged 12–18 years and 525 parents of children aged 0–18 years with an appointment at the pediatric outpatient clinic of a secondary and tertiary medical center. Questionnaires were filled out during their stay at the outpatient clinic. Due to the coronavirus pandemic in 2019 (COVID-19), many consultations were done by phone. These patients received the questionnaires with an information letter at home. Teenagers and parents were asked to complete the questionnaire and return it to the hospital. Questionnaires completed by teenagers were not paired to questionnaires completed by their parents.

For the current ancillary – and original survey – study, a questionnaire was developed assessing demographics and clinical characteristics and teenagers’ and parental attitudes on the use of placebo pills in pediatric clinical care and whether the doctor should be open about prescribing placebos. To test for validity, the draft version of the questionnaire was tested in five teenagers and five parents to ensure that teenagers and parents understood the content and interpreted the questions similarly. This resulted in minor adjustments only. The required time to fulfill the complete survey was approximately 15 min. Before attitudes were assessed, participants were briefly informed about the concept of placebo medication (Table 1). The full version of the questionnaire is accessible upon request (only available in Dutch).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize variables. Multivariable logistic analyses were used to determine potential predictors associated with the willingness to use placebo pills. Significance levels were set α = 0.05 in all analyses. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the St Antonius Hospital. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Amsterdam UMC agreed on participation. Participants provided informed consent for this study by filling out the questionnaires.

Four hundred seventy-eight questionnaires were sent to teenagers and 1166 to parents of patients, of which 751 (45%) questionnaires were completed: 226 (47%) teenagers and 525 (45%) parents. 656/751 (87%) respondents had also filled out the questions of the ancillary placebo study: 200/226 (88%) teenagers and 456/525 (87%) parents. Respondents’ departments included gastroenterology and hepatology (39%), psychosomatic disorder (10%), pulmonology (9%), endocrinology (7%), neurology (5%), urology (4%), infectious diseases (3%), cardiology (2%), and others (21%). Mean (SD) age of teenagers was 14.7 (1.8) years and 114 (57%) of the teenagers were girls. Mean (SD) age of patients for-which parents reported for was 9.7 (5.5) years; 87 (19%) of patients were aged < 4 years, 152 (33%) between 4 and 11 years, and 215 (47%) > 12 years. In total, 233 (51%) of these patients were girls.

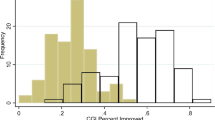

Many participants (508 (77%)) were positive towards prescribing placebo medication: 143 (71%) teenagers vs. 365 (80%) parents (χ2(2) = 5.809, p =.019, Fig. 1). Significant more teenagers agreed on prescribing a placebo with deception (i.e., not disclosing that a placebo is being prescribed) compared to parents (64/143 (45%) vs. 89/365 (24%)), whereas 355/508 (70%) respondents reported that they were willing to receive placebo treatment but only when the physician would disclose that the treatment was a placebo (79/143 (55%) teenagers vs. 276/365 (76%) parents, χ2(1) = 20.259, p <.001). Majority of teenagers and parents agreed to disclose placebo treatment to parents exclusively; 252/276 (91%) of parents agreed to withhold information on the use of a placebo for the child vs. 67/79 (85%) of teenagers. Within the group of teenagers, increasing age was positively associated with the willingness for placebo pills (OR 0.803, 95%CI 0.659–0.979). A positive association was found with a higher level of parental education (OR 0.706, 95%CI 0.526–0.949). In both groups of respondents, sex, medication use, and a history of experienced side effects were not associated with the willingness to use placebo pills.

In the current study, we demonstrated that the majority (77%) of respondents – teenagers and parents – found it appropriate for healthcare professionals to prescribe placebo medication. Most teenagers and parents preferred that the physician fully discloses that the treatment is a placebo. Previous studies however have demonstrated lower treatment effects in patients receiving an open-label placebo than a concealed placebo [8, 11]. Compared to adult care, pediatrics has a unique feature that can solve this apparent paradox of pursuing the maximum effect using concealed placebos versus fulfilling patient’s wishes by being open about the treatment. The fact that parents are legally responsible for their children under the age of 12 years allows disclosing placebo treatment to the parents while concealing it for the young patient: a partly open-label placebo. The optimal advantages of placebo treatment can be achieved without legal infringements.

By law, the situation is different when treating teenagers. Here, clinicians cannot withhold information on placebo use, making an open-label placebo the only possible option for this patient group. Although the results are less compared to concealed placebo, several studies in both adults and children with IBS or functional abdominal pain have demonstrated that open-label placebo treatment can result in clinically meaningful symptom improvement compared to no treatment [12,13,14]. Moreover, some contradictions on treatment effects rates of open-label placebo versus concealed placebo interventions in the literature exist. Limited research suggests that open-label placebo interventions might not be inferior to concealed placebo treatment when provided with compelling rationale [15, 16]. Given the advantages of a placebo (i.e., reduced use of pharmacological therapies with less adverse effects), prescribing open-label placebos is an exciting strategy that needs further exploration in daily care for teenagers.

In the current study, we identified that increasing age and higher parental education were positively associated with the willingness for placebo pills. The possibility that adolescents and parents generally acquired more knowledge through the years about the concept of placebo before filling out our questionnaire may explain these results. In our study, the amount of information about the placebo effect was relatively scarce. Future studies are warranted to assess if more extensive education may positively influence parental and teenagers’ views on placebo usage.

A strength of this study is that we also explored teenagers’ attitudes towards prescribing placebos, while earlier studies investigated only parental attitudes. Secondly, this trial included teenagers and parents from both secondary and tertiary care centers in rural and urban areas, increasing the generalizability of the results. A limitation of this study is that we did not study the influence of ethnicity and culture. It could be hypothesized that differences exist in views on using placebo interventions between certain ethnic and cultural groups.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the willingness of teenagers and parents of pediatric patients to receive placebo medication. Most respondents prefer open-label placebo. Especially for children under the age of 12 years, there is the possibility of disclosing placebo treatment to parents only. Placebo medication becoming more acceptable and integrated into daily care may contribute to a decrease in medication use.

Data availability

Deidentified individual participant data are available upon request.

References

Stewart-Williams S, Podd J (2004) The placebo effect: dissolving the expectancy versus conditioning debate. Psychol Bull 130:324–340

Evers AWM et al (2018) Implications of placebo and nocebo effects for clinical practice: expert consensus. Psychother Psychosom 87:204–210

Wager TD, Atlas LY (2015) The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nat Rev Neurosci 16:403–418

Finniss DG, Kaptchuk TJ, Miller F, Benedetti F (2010) Biological, clinical, and ethical advances of placebo effects. Lancet (London, England) 375:686–695

Hoekman DR et al (2017) The placebo response in pediatric abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr 182:155–163.e7

Fernandes R, Ferreira JJ, Sampaio C (2008) The placebo response in studies of acute migraine. J Pediatr 152:527–534

Bernstein MH et al (2020) Primary care providers’ use of and attitudes towards placebos: an exploratory focus group study with US physicians. Br J Health Psychol 25:596–614

Kam-Hansen S et al (2014) Altered placebo and drug labeling changes the outcome of episodic migraine attacks. Sci Transl Med 6:218ra5

Faria V et al (2017) Parental attitudes about placebo use in children. J Pediatr 181:272–278.e10

de Bruijn CMA et al (2022) Teenagers’ and parental individual needs for side effects information and the influence of nocebo effect education. Patient Educ Couns 107587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2022.107587

Friehs T, Rief W, Glombiewski JA, Haas J, Kube T (2022) Deceptive and non-deceptive placebos to reduce sadness: a five-armed experimental study. J Affect Disord Reports 9:100349

Lembo A et al (2021) Open-label placebo vs double-blind placebo for irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Pain 162:2428–2435

Kaptchuk TJ et al (2010) Placebos without deception: a randomized controlled trial in irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS ONE 5:e15591

Nurko S et al (2022) Effect of Open-label placebo on children and adolescents with functional abdominal pain or irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 176:349–356

Kube T, Kirsch I, Glombiewski JA, Herzog P (2022) Can placebos reduce intrusive memories? Behav Res Ther 158:104197

Locher C et al (2017) Is the rationale more important than deception? A randomized controlled trial of open-label placebo analgesia. Pain 158:2320–2328

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of Gabriella Hamming, Catherijne Knibbe, and Ellen Tromp who participated in the original survey study. Finally, we thank all patients and parents who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

De Bruijn coordinated and participated in data collection, conducted statistical analyses, reviewed the literature, and wrote the manuscript. Benninga participated in patient recruitment, critically revised the protocol, and supervised writing the manuscript. Vlieger is the principal investigator, designed the study, wrote the protocol, participated in patient recruitment, supervised the study, and writing the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the submission of this version of the manuscript and take full responsibility for the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Gregorio Milani.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Bruijn, C.M., Benninga, M.A. & Vlieger, A.M. Teenagers’ and parental attitudes towards the use of placebo pills. Eur J Pediatr 182, 1425–1428 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04801-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04801-4