Abstract

Previous studies conducted mainly among adolescents have found associations between participation in sport organised leisure-time activities (OLTAs) and mental health problems (MHP). Fewer research studies have been performed to primary school-aged children and to organised non-sport OLTAs. Therefore, the objective is to examine whether there is an association between participation in sport and non-sport OLTAs and a high risk of MHP in 4- to 12-year-olds. Data were used on 5010 children from a cross-sectional population-based survey conducted between May and July 2018 in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Associations between sport OLTAs, non-sport OLTAs and breadth of OLTAs and a high risk of MHP were explored using logistic regression models adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, stressful life events and physical activity. Of all children, 58% participated in sport OLTAs and 22% in non-sport OLTAs. The proportion of children with high risk of MHP among participants in sport OLTAs is smaller than among non-participants (OR 0.66, 95% CI: 0.53, 0.81). The proportion of children with high risk of MHP among participants in non-sport OLTAs is smaller than among non-participants (OR 0.69, 95% CI: 0.53, 0.91). The proportion of children with a high risk of MHP among participants in 1 category of OLTAs (OR 0.61, 95% CI: 0.49, 0.76) and in 2–5 categories of OLTAs (OR 0.48, 95% CI: 0.32, 0.71) is smaller than among non-participants.

Conclusion: The proportion of children with high risk of MHP among participants in OLTAs is smaller than among non-participants.

What is Known: • Around 10–-20% of children and adolescents experiences mental health problems. • Sport organised leisure-time activities have been found to be associated with a lower risk of mental health problems in adolescents. | |

What is New: • The proportion of children with a high risk of mental health problems in participants in organised leisure-time activities is smaller than among non-participants. • The proportion of children with a high risk of mental health problems in participants with a higher breadth of organised leisure-time activities is smaller compared to non-participants. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Around 10–20% of children and adolescents experience mental health problems (MHP) [1]. First onset usually occurs during childhood or adolescence [2]. MHP in children include but are not limited to anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or disruptive behaviour disorders [3]. Early intervention can reduce or prevent mental health problems in later life [1]. Hence, gaining more insight in possible modifiable factors contributing to good mental health in childhood is important.

Participating in organised leisure-time activities (OLTAs) may contribute to good mental health in childhood [4]. OLTAs are characterised by having a certain structure, schedule, tend to have clearly defined goals and rules and are focused on skill building [5, 6]. Examples of categories are sport, scouting and theatre lessons. Features that could be present in OLTAs that previously have been found to improve mental health are as follows: safe and appropriate peer interactions, structure and adult supervision, forming of supportive relationships with peers and emphasis on inclusion and a sense of belonging, emphasis on positive social norms, support of efficacy and mattering and skill-building [7]. Moreover, OLTAs can include physical activity as possible feature that could improve child mental health, such as sport OLTAs and scouting. Other kinds of OLTAs may include physical activity (e.g. scouting) but not necessarily or in the same amount. The positive youth development theory (PYD), grounded in the socio-ecological theory, postulates that OLTAs offer opportunities for children to develop relationships and to engage in activities that increase their competence, confidence, connection, character and caring. This could lead to better emotion regulation, positive connections with peers, adults and the larger community and consequently a better mental health [8,9,10,11,12,13]. The breadth, intensity, type, duration and engagement of children in OLTAs might also play a role [5].

Studies reported associations of participation in team and other types of sport OLTAs with better youth mental health [14, 15]. Non-sport OLTAs could also contribute to good child mental health [4–6]. Positive contributions to child mental health have been found but most earlier studies focused on adolescents [16–18]. Research to associations of participating in OLTAs with mental health in primary school-aged children is limited [14, 19,20,21,22,23,24] Associations of participation in OLTAs were mixed. Some of these studies found no association [21, 23]. However, other studies performed in children reported an association between participation in OLTAs and better mental health [14, 19, 20, 22, 24]. Prevention in this particular age group possibly contributes to reducing the risk of MHP among adolescents. Therefore, we aim to examine associations between participating in sport OLTAs, non-sport OLTAs and of the breadth of OLTAs and MHP in a population-based sample of 4- to 12-year-olds. We hypothesised that the proportion of children with a high a risk on MHP among participants in OLTAs is smaller than among non-participants. We studied sport and non-sport OLTAs separately because we hypothesised that the association of sport OLTAs might be different from the association non-sport OLTAs with mental health as was found in previous research in adolescents [16].

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study is performed using anonymous data from a Dutch Public Health survey carried out in 2018 by the municipal public health service in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. This survey was conducted in the context of performing statutory tasks (Public Health Act Netherlands). Observational research with anonymous data does not fall within the ambit of the Dutch Act on research involving human subjects and requires no approval of an ethics review board. The Dutch Code of Conduct for Medical Research allows using anonymous survey data for research purposes without an explicit informed consent [25]. The Dutch Public Health survey that was administered consists of questions about sociodemographic information, mental health, diet, physical health, physical activity, OLTAs, social support, care-use and stressful life events. Random probability sampling from the municipal population register stratified by neighbourhood was performed to create a sample of parents of 0- to 12-year-olds for the Dutch Public Health survey. Children living in healthcare institutions were excluded. All parents were living in Rotterdam when the survey was administered. Parents/caregivers received invitations for one child only (i.e. only one child from children living on the same address was included. The first child that was selected entered the sample.) No further selection criteria were used. Hardcopy invitation letters included information about privacy, content, aim, anonymity and login details for the online questionnaire. A toll-free telephone number was provided for additional questions. Hardcopy questionnaires were enclosed with the first reminder and could be requested in Dutch, English or Turkish. The main caregiver filled out the questionnaire. Non-responders were contacted by telephone and were offered extra help in completing the questionnaire. Parents/caregivers were free to refuse participation by not filling out the questionnaire. In total, 7702 parents/caregivers of 0- to 12-year-olds responded to the Dutch Public Health survey. The response rate was 34% and did not differ upon age or gender of the children.

Study population

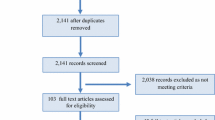

For our study, we used data about 4- to 12-year-olds (n = 5010) as the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) to measure risk of MHP was not assessed in younger children. See Fig. 1 for an overview.

Measurements

Explanatory variables

OLTA participation was measured by the question: ‘Which associations or organizations is your child a member of?’ Parents could choose between categories of OLTAs. The response option was binary (i.e. parents could either answer ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ for each of the OLTAs). Multiple answers were possible:

-

1.

Sport associations;

-

2.

Singing, music or theatre clubs/lessons;

-

3.

Scouting;

-

4.

Craft club;

-

5.

Different kind of organisation;

-

6.

None.

We computed three variables out of these items: sport OLTAs, non-sport OLTAs and breadth of OLTAs. Participation in sport OLTAs was based on item 1 and was categorised as ‘Sport OLTA participation’ and ‘No sport OLTA participation’ using the latter as reference group. Participation in non-sport OLTAs was based on items 2, 3, 4 and 5 and categorised as ‘non-sport OLTA participation’ and ‘No non-sport OLTA participation’ using the latter as reference group. We computed different variables for sport and non-sport OLTAs because as they may differ with respect to physical activity levels and also for comparison purposes with previous studies [26]. We chose to combine all non-sport OLTAs to ensure sufficient children in each category. In some of the non-sport OLTAs, only a small amount of children were participating (i.e. singing, music, theatre = 11.2%, scouting = 2.0%, craft club = 2.5%, other = 8.5%). The breadth of OLTAs was based on all six items and categorised as ‘2–5 categories’, ‘1 category’ and ‘None’, using the latter as reference group. This variable includes different categories of OLTAs to capture the breadth. We chose for this categorisation to ascertain sufficient children in each category (i.e. 1 category = 55.1%, 2 categories = 11.0%, 3 categories = 1.3%, 4 categories = 0.1% and 5 categories = 0.02%).

Study outcome

We computed the risk of MHP using the parent-reported strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) which was embedded in the public health survey. The SDQ measures risk of MHP but not MHP. The SDQ is a validated questionnaire (the SDQ has good validity compared to the Child Behaviour Checklist in the original and in Dutch versions as well as good overall reliability) to measure risk of MHP and consists of five domains: emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems and prosocial behaviour [27–30]. The total difficulties score was calculated by adding the scores of all domains except for prosocial behaviour (range = 0–40) (Cronbach’s α = 0.73). We dichotomised the total difficulties score using age-dependent cut-off scores to either ‘High risk of MHP’ or a ‘Normal score’ with the latter as reference group. For 4- to 7-year-olds, a total difficulties score of ≥ 15 indicates risk of MHP and for 7- to 12-year-olds a cut-off is ≥ 14 indicates risk of MHP [27, 28].

Covariates

Gender, age, family situation, parental education, migrant status, perceived financial difficulties, current stressful life events and adequate physical activity were selected based on theory and previous research and were derived from the survey [4–6]. Gender or age can affect participation rates and have found to be associated with MHP [4, 5, 26]. Minority- and disadvantaged groups generally participate less in OLTAs [5, 31]. Moreover, they may be more at risk to develop MHP just as children who experience stressful life events, who live in low SES families or not in a two-parent family [32–34]. Physical activity is a key aspect of sport OLTAs and could be present in non-sport OLTAs and may be associated with better mental health in children [35]. Age was measured continuously in years. Gender was measured as ‘Girl’ or ‘Boy’. Family status was measured as ‘Two-parent family’ or ‘Single-parent/other type of family’. Parental educational level was defined as highest parental educational level obtained and categorised as ‘lower education’ (no education, primary school or ≤ 4 years general secondary school), ‘intermediate education’ (> 4 years general secondary school or intermediate vocational training) and ‘higher education’ (higher vocational training, university degree or higher) [36]. Parent-reported migrant status of the child was measured as ‘Non-Western’ or ‘Non-Dutch Western’ and ‘Dutch’. A non-Western migrant status was assigned when the child itself or either one or both of the parents were born in a non-Western country. A non-Dutch Western migrant status was assigned when the child itself or either one or both of the parents were born in a Western country different from the Netherlands [37]. Perceived financial difficulties was measured by the question: ‘Did you experience any difficulties in making ends meet in the past twelve months with your household income?’ Perceived financial difficulties had four answer categories and was dichotomised as ‘No financial difficulties’ (‘No’ and ‘No but I have to think about my expenses’) and ‘Financial difficulties’ (‘Yes a little’ and ‘Yes’). Current stressful life events was measured by eighteen stressful life events (e.g. ‘Divorce of parents’). In case of ≥ 1 stressful life events currently experienced, this variable was categorised as ‘Yes’. In case of no current stressful life events, this variable was categorised as ‘No’. Physical activity was measured by eight questions about five physical activity domains: commuting to school, by outdoor-play, by physical education or swimming lessons at school and by sport club membership. All questions concerned the past week. Parents answered the number of days for an activity (answer categories ‘1 day’, ‘2 days’, ‘3 days’, ‘4 days’, ‘5 days’, ‘6 days’, ‘7 days’, ‘none’, ‘not the past week but normally yes’) followed by a question on the minutes per day (answer categories ‘ < 10 min’, ‘10–20 min’, ‘20–30 min’, ‘30–60 min’, ‘ > 60 min’ or ‘Not applicable’). These physical activity questions are used by health services in the Netherlands and scored in minutes per week, which was changed to hours per day for the present study.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated and chi-square and Mann–Whitney U tests were performed to test for differences between OLTA participation. Multiple imputation (m = 10) with the fully conditional specification method was used for missing values of variables (total 0.7% ranging from 0.3 to 4.0%) using data on explanatory variables, outcome variables and covariates as predictors [38]. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to examine associations between participating in OLTAs and a high risk of MHP. We computed three models separate for sport OLTAs and for non-sport OLTAs and consecutively a fourth model which is a combined model for both explanatory variables (sport and non-sport OLTAs). Model 1 was a crude model. Model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, parental education, family status, perceived financial difficulties and migrant status of the child. Model 3 was additionally adjusted for current stressful life events and physical activity. Model 4 is model 3 and additionally mutually adjusted for sport OLTAs and non-sport OLTAs to examine independent associations (combined model). Multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine the association between the breadth of OLTAs and a high risk of MHP were also performed. Three models similar to models 1, 2 and 3 for sport and non-sport OLTAs were computed. To examine whether the impact differed upon groups with different characteristics, interactions between age, gender, family status, migrant status, perceived financial difficulties and sport OLTAs, non-sport OLTAs and breadth of OLTAs were tested by adding the product terms of the explanatory variables with each of the potential effect modifiers separately to the full model (model 4 for sport and non-sport OLTAs and model 3 for breadth of OLTAs) [5, 13, 16]. Interactions between participating in sport and non-sport OLTAs were tested likewise [5, 13]. Interactions were considered present at a significance level of p < 0.05 and none was found (Table S1).

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses using a complete-case dataset were conducted for comparison. Missing-value analysis was performed using descriptive characteristics and chi-square or Mann–Whitney U tests for differences between children without and with missing values. These analyses are included in the supplementary material (Tables S2 and S3 are about complete-case analyses, and Table S4 is about missing-value analysis).

Two-tailed analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics version 25 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the population characteristics. Median age was 8.0 (IQR = 6.0–10.0). The sample consisted of 48% girls. Of all children, 58% participated in sport OLTAs, 22% participated in non-sport OLTAs and 32% in none. In our sample, 55% participated in 1 category of OLTAs and 13% in 2–5 categories of OLTAs. Generally, more boys participated in organised sport OLTAs and more girls in non-sport OLTAs. Children with lower educated parents, with parents perceiving financial difficulties and with a non-Western migrant status participated less in sport OLTAs.

Table 2 presents associations between OLTAs and a high risk of MHP. After adjustment for confounders, the proportion of children with a high risk of MHP among participants in sport OLTAs (OR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.53, 0.81) is smaller compared to non-participants (model 4). The proportion of children with a high risk of MHP among participants in non-sport OLTAs (OR 0.69, 95% CI: 0.53, 0.91) is smaller than among non-participants (model 4).

Table 3 presents associations between the breadth of OLTAs and a high risk of MHP. The proportion of children with a high risk of MHP among participants participating in 1 (OR 0.61, 95% CI: 0.49, 0.76) or in 2–5 (OR 0.48, 95% CI: 0.32, 0.71) categories is smaller than among non-participants (model 3).

Complete-case analyses yielded similar estimates (Tables S2 and S3). Participating in non-sport OLTAs was non-significant in model 2 and model 3.

Comparisons between children with complete data (n = 4716) and with missing values (n = 294) on included variables indicated differences for family situation, parental education, perceived financial difficulties, migrant status, risk of MHP, age, sport OLTAs and breadth of OLTAs (Table S4).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine associations between participating in OLTAs and risk of MHP in a population-based sample of 4- to 12-year-olds. We demonstrated that the proportion of 4- to 12-year-olds with a high risk of MHP among participants in sport or non-sport OLTAs is smaller compared to non-participants. The proportion of children with a high risk of MHP among participants in 1 category of OLTAs is smaller compared to non-participants. The proportion of children with a high risk of MHP among participants in 2–5 categories (i.e. higher breadth) of OLTAs was even smaller compared to non-participants.

The findings of this study support the hypothesis postulated by the PYD-theory that participation in OLTAs could improve academic, psychological, social and behavioural outcomes in youth and should therefore be encouraged [5]. This is because according to the PYD-theory OLTAs may offer a opportunities for children to develop relationships and to engage in activities that increase their competence, confidence, connection, character (e.g. respecting societal and cultural rules, sense of morality and integrity) and caring (i.e. the so-called 5 Cs) leading to better emotion regulation and positive connections with peers, adults and others [8–13]. This in turn could be protective for their mental health. Our findings are in agreement with earlier studies that also found an association between OLTAs and mental health in children and adolescents [14, 19, 20, 22, 24, 39]. In our study sample, 32% was not participating in any OLTA. Of all children, 58% participated in sport OLTAs and 22% in non-sport OLTAs. This is consistent with a study among Canadian 6- to 12-year-olds in which 39% was not participating in OLTAs [18]. The HBSC studies among nine nationally representative samples of 11-, 13- and 15-year-olds showed that 18% of the children was not participating in OLTAs but these children were somewhat older [26].

Sport OLTAs include several features mentioned by the PYD-theory that have been found to improve mental health. Due to these features, OLTAs could also contribute to good mental health. For example by offering children a place to develop executive functioning which is a precursor of behavioural regulation in childhood [40, 41]. Neville et al. also postulated that the structured, scheduled meetings, role-based, rule-governed and goal-oriented nature of these activities make them suitable for promoting beneficial developmental outcomes, such as behavioural regulation [22]. In their study, they observed that for boys with development delays, regular participation in sport OLTAs was longitudinally associated with a relative decrease in behavioural difficulties [22]. Indeed, previous studies into sport OLTAs already reported associations with better mental health in children. However, most did not adjust for physical activity [16, 42, 43]. It has been observed that physical activity itself is associated with child mental health [35]. Physical activity is also a one of the foundation stones of most of the sport OLTAs. A consequence is that it is impossible to differentiate between benefits due to participating in sport OLTAs or due to physical activity in these studies. We have adjusted for physical activity in our analyses and still found that the proportion of children with high risk of MHP among participants in sport OLTAs is smaller than among non-participants. The finding that participating in sport OLTAs is negatively associated with risk of MHP among participants, besides by increasing physical activity, supports the PYD-theory [8–12, 44]. Also in another study, lower total difficulties scores on the SDQ and less internalising problems were observed among children participating in sport OLTAs compared to non-participants after adjustment for physical activity [14].

Similarly, non-sport OLTAs also consist of several features that could contribute to good mental health and share features similar to features of sport OLTAs. Therefore, also participation in non-sport OLTAs could contribute to good mental health. Indeed, it has been found in previous research that participation in non-sport OLTAs is associated with conduct problems mediated by social skills [24]. In adolescents, it has been found to be associated with lower emotional-anxiety, higher pro-social behaviour and higher self-image just as participation in sport OLTAs [45]. That non-sport OLTAs are associated with mental health in children is supported by the findings in our study because the proportion of children with high risk of MHP among participants in non-sport OLTAs is smaller than among non-participants. This is in agreement with some previous studies that observed that participation in non-sport OLTAs might be associated with better mental health in children but research is inconclusive [18, 26, 46]. Among 27,121 Canadian 6- to 12-years-olds, no differences in mental health were found between children who did or did not participate in educational programs, arts/music and individual sport [18]. A possible explanation may be that they included children participating in educational programs to meet parental expectations leading to lower levels of mental health [18]. Contrary, data from the HBSC studies observed that both sport and non-sport OLTAs were associated with better mental well-being and fewer psychological complaints [26].

Previously, concerns were raised that participation in more OLTAs does not contribute to better mental health but in fact could increase risk of MHP [47]. A higher breadth of OLTAs was hypothesised as too time-consuming, an indication of parental pressure, costing to much free time and being too competitive and thus leads to poor developmental outcomes. This is also known as the over-scheduling hypothesis [47]. In our sample, the proportion of children with a high risk of MHP among participants in 2–5 categories of OLTAs was smaller than among participants in 1 category and among non-participants. However, confidence intervals of the estimates were overlapping. Most of the children participating in 2–5 categories of OLTAs participated in 2 categories; thus, we could not study whether there was some form of over-scheduling. Other studies reported associations of a higher breadth of OLTAs with better mental health [47, 48]. This could be because it leads to more developmental opportunities in different contexts [47, 48].

Strengths of this study are the population-based setting, large sample size and validated questionnaire for assessment of the risk of MHP. We adjusted for physical activity, showing that the associations of participating in sport OLTAs with mental health possibly also originates from another pathway than through physical activity itself. This study also has some limitations. Due to the cross-sectional design, no causation or temporal direction can be established. We adjusted for several covariates but residual confounding might be present because of incompletely or unmeasured confounders such as socioeconomic status indicators. Fewer disadvantaged children participated in OLTAs and we could only adjust for parental education, perceived financial difficulties and migrant status. The survey data were not nationally representative possibly reducing the generalisability. The response rate was 34%, which makes the study prone to selection bias, but low response rates do not automatically introduce bias in estimates or limit generalisability [49]. Moreover, surveys in the same Dutch city have similar response rates [50]. Data were collected in 2018 before the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the data and the results may not reflect the situation after the COVID-19 outbreak. Generalising these results to a situation after the COVID-19 outbreak should be done with caution. Data about MHP were parent-reported. This could lead to social-desirable answers from parents about their children. Furthermore, the mental health state of the parents could also influence the answers on the SDQ. A study from 2001 observed that mentally healthy mothers might underreport and that parents with MHP might over report MHP in children [51]. We have no information about the frequency, intensity or duration or if OLTAs were individual or group-based. Finally, the Nagelkerke R2 values of our models were relatively low, even in the adjusted models. The Nagelkerke R2 is a relative measure that indicates how well the model explains the data. Even though we observed significant associations, we should interpret our models with caution.

Public health implications

The findings of this study demonstrate that the proportion of children with a high risk of HP among participants in both sport and non-sport OLTAs is smaller compared to non-participants. This supports earlier studies that observed associations between participation in OLTAs and mental health in adolescents and the few studies that examined this in children. As we adjusted for physical activity, our study indicates that the beneficial effects of OLTAs might originate from other features specific for OLTAs.

Preventive policies could contribute to good mental health by stimulating more children to participate in OLTAs. Municipalities can increase the availability and amount of local clubs/associations and schools could offer additional extracurricular OLTAs [52].

Future research

We recommend studying OLTAs more in depth by focusing on specific activities and its features [53, 54]. For example whether the association with mental health in children differs upon the content of the design (how inclusive it is, degree of structure), content (to which degree does it integrates cognitive, socio-emotional, motor skills), the environment (e.g. extracurricular at school or community) or on the resources (indoor/outdoor, level of adult involvement, equipment) of the activity [54]. Furthermore, we recommend studying aspects of OLTAs such as characteristics of trainers and group of peers participating in OLTAs [12]. Studying associations between OLTAs and mental health in children with developmental and/or physical disabilities is also recommended as these children are generally excluded from research [54]. It is of particular importance that future studies also examine potential determinants for participation/non-participation and how policymakers can ensure that more children can and will participate in such activities.

Conclusions

In this population-based sample of 5010 primary school-aged children, the proportion of children with a high risk of MHP among participants in OLTAs is smaller compared to non-participants. This was observed for participants in sport OLTAs as well as for participants in non-sport OLTAs irrespective of physical activity levels. In this sample of 4- to 12-year-olds, an association of a higher breadth of OLTAs with a lower risk of MHP in 4- to 12-year-old children was also observed.

Availability of data and material

The data used in this study are protected by the Municipal Health Service of Rotterdam. Data are available under request via gezondheidsmonitorbco@rotterdam.nl.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- MHP:

-

Mental health problems

- PYD:

-

Positive youth development

- SDQ:

-

Strengths and difficulties questionnaire

References

Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, Rohde LA, Srinath S, Ulkuer N, Rahman A (2011) Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet 378:1515–1525

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:593–602

Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA (2015) Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56:345–365

Bohnert AM, Garber J (2007) Prospective relations between organized activity participation and psychopathology during adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 35:1021–1033

Bohnert A, Fredricks J, Randall E (2010) Capturing unique dimensions of youth organized activity involvement: theoretical and methodological considerations. Rev Educ Res 80:576–610

Mahoney JL, Larson RW, Eccles JS, Lord H (2005) Organized activities as developmental contexts for children and adolescents. Organized activities as contexts of development: Extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs 3–22

Mahoney JL, Larson RW, Eccles JS, Lord H (2005) Organized activities as developmental contexts for children and adolescents: extracurricular activities, after school and community programs. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mawah NJ

Agans JP, Vest Ettekal A, Erickson K, Lerner RM (2016) Positive youth development through sport. Positive youth development through sport 34–44

Fraser-Thomas JL, Côté J, Deakin J (2005) Youth sport programs: an avenue to foster positive youth development. Phys Educ Sport Pedagog 10:19–40

Lerner RM, Lerner JV (2012) Waves of the future: the first eight years of the 4-H study of positive youth development

Benson PL, Scales PC, Hamilton SF, Sesma Jr A (2006) Positive youth development: theory, research, and applications

Holt NL, Deal CJ, Pankow K (2020) Positive youth development through sport. Handbook of sport psychology 429–446

Mahoney J, Vandell D, Simpkins S, Zarrett N (2009) Adolescent out‐of‐school activities 228–269

Vella SA, Cliff DP, Magee CA, Okely AD (2015) Associations between sports participation and psychological difficulties during childhood: a two-year follow up. J Sci Med Sport 18:304–309

Sabiston CM, Jewett R, Ashdown-Franks G, Belanger M, Brunet J, O’Loughlin E, O’Loughlin J (2016) Number of years of team and individual sport participation during adolescence and depressive symptoms in early adulthood. J Sport Exerc Psychol 38:105–110

Badura P, Geckova AM, Sigmundova D, van Dijk JP, Reijneveld SA (2015) When children play, they feel better: organized activity participation and health in adolescents. BMC Public Health 15:1090

Oberle E, Ji XR, Guhn M, Schonert-Reichl KA, Gadermann AM (2019) Benefits of extracurricular participation in early adolescence: associations with peer belonging and mental health. J Youth Adolesc 48:2255–2270

Oberle E, Ji XR, Magee C, Guhn M, Schonert-Reichl KA, Gadermann AM (2019) Extracurricular activity profiles and wellbeing in middle childhood: a population-level study. PLoS ONE 14:e0218488

Moeijes J, van Busschbach JT, Bosscher RJ, Twisk JWR (2018) Sports participation and psychosocial health: a longitudinal observational study in children. BMC Public Health 18:702

Schumacher Dimech A, Seiler R (2011) Extra-curricular sport participation: a potential buffer against social anxiety symptoms in primary school children. Psychol Sport Exerc 12:347–354

Fletcher AC, Nickerson P, Wright KL (2003) Structured leisure activities in middle childhood: links to well-being. J Community Psychol 31:641–659

Neville RD, Guo Y, Boreham CA, Lakes KD (2021) Longitudinal association between participation in organized sport and psychosocial development in early childhood. J Pediatr 230(152–160):e151

Howie EK, McVeigh JA, Smith AJ, Straker LM (2016) Organized sport trajectories from childhood to adolescence and health associations. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48:1331–1339

Denault A-S, Déry M (2014) Participation in organized activities and conduct problems in elementary school: the mediating effect of social skills. J Emot Behav Disord 23:167–179

Council of the Federation of Medical Scientific Societies (2018) Codes of conduct. The code of conduct for the use of data in health research

Badura P, Hamrik Z, Dierckens M, Gobina I, Malinowska-Cieslik M, Furstova J, Kopcakova J, Pickett W (2021) After the bell: adolescents’ organised leisure-time activities and well-being in the context of social and socioeconomic inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 75:628–636

Goodman R (2001) Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:1337–1345

Theunissen MHC, De Wolff MS, Van Grieken A, Mieloo C (2016) Manual for the use of the SDQ within youth health care. Questionnaire for identifying psychosocial problems in 3–17 year olds 2016 TNO, Leiden

Mieloo C, Raat H, van Oort F, Bevaart F, Vogel I, Donker M, Jansen W (2012) Validity and reliability of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in 5–6 year olds: differences by gender or by parental education? PLoS ONE 7:e36805–e36805

Vogels AGC, Crone MR, Hoekstra F, Reijneveld SA (2009) Comparing three short questionnaires to detect psychosocial dysfunction among primary school children: a randomized method. BMC Public Health 9:489–489

Heath RD, Anderson C, Turner AC, Payne CM (2018) Extracurricular activities and disadvantaged youth: a complicated—but promising—story. Urban Education 0042085918805797

Belhadj Kouider E, Koglin U, Petermann F (2014) Emotional and behavioral problems in migrant children and adolescents in Europe: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 23:373–391

Reiss F, Meyrose AK, Otto C, Lampert T, Klasen F, Ravens-Sieberer U (2019) Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents: results of the German BELLA cohort-study. PLoS ONE 14:e0213700

Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S et al (2010) Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry 197:378–385

Biddle SJ, Asare M (2011) Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews. Br J Sports Med 45:886–895

Statistics Netherlands (2004) Dutch standard classification of education 2003. Voorburg/Heerlen: Statistics Netherlands

Statistics Netherlands. Person with a non-western migration background. https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/our-services/methods/definitions/person-with-a-non-western-migration-background

van Ginkel JR, Linting M, Rippe RCA, van der Voort A (2020) Rebutting existing misconceptions about multiple imputation as a method for handling missing data. J Pers Assess 102:297–308

Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR (2013) A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 10:135

Donnelly JE, Hillman CH, Castelli D, Etnier JL, Lee S, Tomporowski P, Lambourne K, Szabo-Reed AN (2016) Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48:1197

Ishihara T, Sugasawa S, Matsuda Y, Mizuno M (2017) Relationship of tennis play to executive function in children and adolescents. Eur J Sport Sci 17:1074–1083

Evans MB, Allan V, Erickson K, Martin LJ, Budziszewski R, Cote J (2017) Are all sport activities equal? A systematic review of how youth psychosocial experiences vary across differing sport activities. Br J Sports Med 51:169–176

Panza MJ, Graupensperger S, Agans JP, Dore I, Vella SA, Evans MB (2020) Adolescent sport participation and symptoms of anxiety and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol 1–18

National Research Council (2002) Community programs to promote youth development. National Academics Press

Guèvremont A, Findlay L, Kohen D (2014) Organized extracurricular activities: are in-school and out-of-school activities associated with different outcomes for Canadian youth? J Sch Health 84:317–325

Bungay H, Vella-Burrows T (2013) The effects of participating in creative activities on the health and well-being of children and young people: a rapid review of the literature. Perspect Public Health 133:44–52

Mahoney JL, Vest AE (2012) The over-scheduling hypothesis revisited: intensity of organized activity participation during adolescence and young adult outcomes. J Res Adolesc 22:409–418

Sharp EH, Tucker CJ, Baril ME, Van Gundy KT, Rebellon CJ (2015) Breadth of participation in organized and unstructured leisure activities over time and rural adolescents’ functioning. J Youth Adolesc 44:62–76

Davern M, McAlpine D, Beebe TJ, Ziegenfuss J, Rockwood T, Call KT (2010) Are lower response rates hazardous to your health survey? An analysis of three state telephone health surveys. Health Serv Res 45:1324–1344

Mölenberg FJM, de Vries C, Burdorf A, van Lenthe FJ (2021) A framework for exploring non-response patterns over time in health surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 21:37–37

Najman J, Williams GM, Nikles J, Spence S, Bor W, O’Callaghan M, Le Brocque R, Andersen M, Shuttlewood G (2001) Bias influencing maternal reports of child behavior and emotional state. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 36:186–194

Somerset S, Hoare DJ (2018) Barriers to voluntary participation in sport for children: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr 18:47

Vazou S, Pesce C, Lakes K, Smiley-Oyen A (2019) More than one road leads to Rome: a narrative review and meta-analysis of physical activity intervention effects on cognition in youth. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 17:153–178

Stodden D, Lakes KD, Côté J, Aadland E, Benzing V, Brian A, Draper CE, Ekkekakis P, Fumagalli G, Laukkanen A, Mavilidi MF, Mazzoli E, Neville RD, Niemistö D, Rudd J, Sääkslahti A, Schmidt M, Tomporowski PD, Tortella P, Vazou S, Pesce C (2021) Exploration: an overarching focus for holistic development. Brazilian Journal of Motor Behavior 15:301–320

Acknowledgements

We thank the municipality of Rotterdam for providing the data from the Dutch Public Health survey carried out in 2018 by the Municipal Public Health Service in the city of Rotterdam.

Funding

This work was funded by a research grant (project number: 531001313) from ZonMw, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. ZonMw has no role in any part of the research, writing and reviewing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: Mirte Boelens, Michel S. Smit, Wilma Jansen and Hein Raat; methodology: Mirte Boelens, Wilma Jansen and Hein Raat; formal analysis and investigation: Mirte Boelens, Wilma Jansen and Hein Raat; writing – original draft preparation: Mirte Boelens; writing – review and editing: Michel S. Smit, Wilma Jansen, Hein Raat, Dafna A. Windhorst, Harrie J. Jonkman, Clemens M. H. Hosman; funding acquisition: Wilma Jansen, Hein Raat, Dafna A. Windhorst, Harrie J. Jonkman, Clemens M. H. Hosman; supervision: Wilma Jansen and Hein Raat. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Our study relied on anonymous survey data collected in the context of performing statutory tasks (Public Health Act Netherlands). Observational research with anonymous data does not require the approval of an ethics review board because it falls outside the ambit of the Dutch Act on research involving human subjects.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Gregorio Paolo Milan

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boelens, M., Smit, M.S., Windhorst, D.A. et al. Associations between organised leisure-time activities and mental health problems in children. Eur J Pediatr 181, 3867–3877 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04591-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04591-9