Abstract

Evidence on the use and efficacy of medical cannabis for children is limited. We examined clinical and epidemiological characteristics of medical cannabis treatment and caregiver-reported effects in children and adolescents in Switzerland. We collected clinical data from children and adolescents (< 18 years) who received Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabidiol (CBD), or a combination of the two between 2008 and 2019 in Switzerland. Out of 205 contacted families, 90 agreed to participate. The median age at the first prescription was 11.5 years (interquartile range (IQR) 6–16), and 32 patients were female (36%). Fifty-one (57%) patients received CBD only and 39 (43%) THC. Patients were more likely to receive THC therapy if one of the following symptoms or signs were present: spasticity, pain, lack of weight gain, vomiting, or nausea, whereas seizures were the dominant indication for CBD therapy. Improvements were reported in 59 (66%) study participants. The largest treatment effects were reported for pain, spasticity, and frequency of seizures in participants treated with THC, and for those treated with pure CBD, the frequency of seizures. However, 43% of caregivers reported treatment interruptions, mainly because of lack of improvement (56%), side effects (46%), the need for a gastric tube (44%), and cost considerations (23%).

Conclusions: The effects of medical cannabis in children and adolescents with chronic conditions are unknown except for rare seizure disorders, but the caregiver-reported data analysed here may justify trials of medical cannabis with standardized concentrations of THC or CBD to assess its efficacy in the young.

What is Known: • The use of medical cannabis (THC and CBD) to treat a variety of diseases among children and adolescents is increasing. • In contrast to adults, there is no evidence to support the use of medical cannabis to treat chronic pain and spasticity in children, but substantial evidence to support the use of CBD in children with rare seizure disorders. | |

What is New: • This study provides important insights into prescription practices, dosages, and treatment outcomes in children and adolescents using medical cannabis data from a real-life setting. • The effects of medical cannabis in children and adolescents with chronic conditions shown in our study support trials of medical cannabis for chronic conditions. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Cannabis sativa, commonly known as cannabis, contains more than 600 ingredients. Among them are more than 100 phytocannabinoids, which include the substance Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) [1]. THC is best known for its psychotropic effect, but THC-containing products are also used to alleviate pain, spasticity, vomiting, nausea, and loss of appetite. Drugs containing THC have been used to treat these symptoms in children with cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorders, and Tourette syndrome [2–5]. In addition to THC, cannabis contains the phytocannabinoid cannabidiol (CBD), which has anti-inflammatory, antiepileptic, antipsychotic, and anxiety-relieving properties [6]. In children, CBD has been mainly used to treat epilepsy [2, 7–10], anxiety [11, 12], and autism [12, 13]. There is substantial evidence to support the use of CBD in children with rare seizure disorders, but the evidence is lacking for other types of seizures and medical conditions [2, 7–10]. However, knowledge about the use and efficacy of medical cannabis is limited beyond these conditions. Therefore, this study provides important insights into prescription practices, dosages, and treatment outcomes in children and adolescents using medical cannabis data from a real-life setting in Switzerland.

Synthetic or natural cannabis-containing preparations with more than 1% THC are regulated as narcotic drugs in Switzerland [14]. In 2011, a revision of the Swiss Law on Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances (Narcotics Law) authorized the Federal Office of Public Health to issue exceptional licenses for the medical use of substances containing more than 1% THC [15]. In contrast, pure CBD-containing preparations do not require exceptional authorizations for the prescription to patients [15, 16]. At present, several oral THC-containing preparations are prescribed as extemporaneous formulations in Switzerland with exceptional permission from the federal authorities. Until the end of April 2019, only two pharmacies (‘Bahnhof Apotheke Langnau AG’ and ‘Apotheke zur Eiche AG’) were authorized to produce THC-containing preparations for medical use.

In a previous study, we examined the requests for medical use of cannabinoids submitted to the Federal Office of Public Health in 2013 and 2014. We found that exceptional licenses for medical use of cannabinoids increased (from 542 patients treated in 2013 to 825 in 2014), with 1193 unique patients receiving treatment with cannabinoids [17]. Only 14 patients (1.2%) were younger than 20 years. Since then, the number of children and adolescents receiving medical cannabis has increased. Here, we examined the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of medical cannabis treatment and caregiver-reported effects in children and adolescents in Switzerland from February 2008 to June 2019.

Methods

Study design and data collection

This is a retrospective observational study that collected data from patients’ families. We obtained a list of all children and adolescents under 18 years of age who received medical THC- or CBD-containing preparations between February 2008 and June 2019 from the ‘Bahnhof Apotheke Langnau AG’ pharmacy in Langnau, Switzerland. The children and adolescents who received medical cannabis preparations from the pharmacy in Langnau came from all regions in Switzerland. The pharmacy in Langnau was one of two pharmacies in Switzerland authorized by the authorities to provide medical cannabis, as prescribed by the treating physician. The patient list included details on the date of birth, sex, medical diagnosis, date of prescriptions, the preparations including the concentration of CBD or THC, and the patients’ and the prescribing physicians’ contact details.

We developed and piloted a standardized questionnaire in collaboration with an advisory panel consisting of two pharmacists and three clinicians with experience with medical cannabis. We piloted the German and French version of the questionnaire with caregivers for completeness and understandability. The questionnaire had three sections: (i) basic information such as sex, age, diagnosis, medications other than medical cannabis, and non-pharmacological therapies; (ii) details on the medical cannabis therapy, including the symptoms triggering therapy, type of medical cannabis, initial and current or last dosage, side effects, treatment interruptions, and treatment effects; and (iii) costs of cannabis therapy, including coverage of the expenses by health insurance or out of pocket. An English translation of the questionnaire is reproduced in the supplemental information (Table S1). We assessed treatment effects using a Likert scale with options ranging from ‘much less’, ‘less’, ‘no change’, ‘more’, to ‘much more’. The survey was provided in paper form or electronically in a REDCap application [18].

We sent all children and adolescents’ caregivers an invitation letter with information on the study, the informed consent form, and the questionnaire with a prepaid return envelope. We sent non-responders another questionnaire 4–6 weeks later. In the event of continued nonresponse, we contacted families by phone. Depending on the caregivers’ preference, either a caregiver or the adolescent (≥ 14 years old) or both filled in the questionnaire.

Definitions

We assigned children and adolescents to two groups: those treated with a pure CBD preparation and those treated with a THC-containing preparation (with or without low concentrations of CBD). Patients treated with both THC and pure CBD were analysed in the THC group. In other words, patients who received THC, and an additional preparation of pure CBD, were included in the THC group. The medical cannabis preparations were standardized for THC or CBD concentration. The pure THC solution (dronabinol solution 2.5%) contained 0.7 mg THC per drop, the standardized alcohol-based cannabis tincture (10 mg THC/ml and 20 mg CBD/ml) 0.3 mg THC and 0.6 mg CBD per drop, and the standardized cannabis oil (10 mg THC/ml and 20 mg CBD/ml) 0.4 mg THC and 0.8 mg CBD per drop. The pure CBD solutions with concentrations of 2.5%, 5%, and 10% contained 0.7 mg, 1.4 mg, and 2.8 mg per drop, respectively [19, 20].

We categorized the diagnosis by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), version 2019, into nine groups (ICD-10 codes in parentheses):

-

• Infectious and parasitic diseases (A00-B99).

-

• Cancer (C00–C97).

-

• Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (E00-E90).

-

• Mental and behavioural disorders (F00–F99).

-

• Diseases of the nervous system (G00–G99).

-

• Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (L00-L99).

-

• Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (M00-M99).

-

• Congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities (Q00-Q99).

-

• Injury, poisoning, and other conditions with external causes (S00–S99).

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize patients and treatment effects and assessed differences between groups using chi‐square, Fisher’s exact, or Wilcoxon rank‐sum tests. We assessed changes in the dosage of products using the paired t-test. All analyses were done in Stata (version 15.1, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics

The Cantonal Ethics Committee Bern, Switzerland, approved this study (No. 2019–00,049). Written informed consent was obtained from the caregivers of each child or adolescent younger than 14 years. Among older adolescents, either the adolescent or the caregivers gave informed consent.

Results

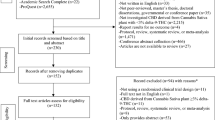

The patient list of the pharmacy included data on 205 children or adolescents who were treated with THC- or CBD-containing preparations between February 2008 and June 2019. The first prescription to a child or adolescent was in 2013. Initially, we received 77 responses from caregivers. After the reminders, 90 caregivers (43.9%) agreed to participate in the study. Figure 1 shows the recruitment into the study. We compared the characteristics of the 90 participating children or adolescents to the 115 patients who did not participate. There were no differences in age and the type of medical cannabis prescribed. Compared to non-responders, participants were more likely to be male, to have more than one ICD-10 diagnosis, to have a disease of the nervous system or an endocrine, nutritional and metabolic disease, and have multiple prescriptions of medical cannabis products. According to the ICD-10 classification, the most common diseases among the 205 children or adolescents were diseases of the nervous system (120; 59%), mental and behavioural disorders (26; 13%), cancer (15; 7%), congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities (15; 7%), and endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (11; 5%). For 34 (17%), the diagnosis was missing (Table S2).

Patient characteristics

The median age at the first prescription of the 90 participants was 11.5 years (interquartile range 6–15), and 32 were female (36%, Table 1). The youngest participant was 4 months old with a neurodegenerative disease and the oldest 17 years old with epilepsy. Both received CBD only to treat seizures. More than half of the participants (57%) suffered from more than one disease. The most common diagnosis were epilepsy (66; 73%), cerebral palsy (32; 36%), encephalopathy (15; 17%), metabolic diseases (8; 9%), and autism (7; 7%). Among the 66 participants with epilepsy, 24 (36%) had only epilepsy, whereas 42 (64%) had epilepsy with additional diseases (Table S3).

Fifty-one participants (57%) were treated with CBD only and 39 (43%) with a THC preparation. Six patients who received a THC-containing preparation and pure CBD (three received dronabinol and 2.5%, 5%, or 10% pure CBD; two cannabis tincture and 5% or 10% pure CBD; and one cannabis oil and 2.5% CBD) were included in the THC group. When analysing the groups ‘THC only’ and ‘THC and CBD’, we found no statistical difference (Table S4). THC was more commonly prescribed to participants with cancer (p = 0.03), whereas CBD only was more frequently prescribed to participants with epilepsy (p < 0.001). Participants were more likely to receive THC therapy if one of the following symptoms or signs were present: spasticity, pain, lack of weight gain, loss of appetite, vomiting, or nausea, whereas seizures were the dominant indication for CBD only therapy. The daily dosage of medical cannabis preparations increased over time for both THC- and CBD-only preparations (Fig. 2).

The majority of participants (72; 80%) received at least one concomitant medication. The most frequent medication categories were antiepileptic drugs (60; 67%), followed by muscle relaxants (10; 11%), analgesics (10; 11%), and other drugs (25; 28%). Also, 63 (70%) participants received physical therapy, 46 (51%) occupational therapy, and 23 (26%) osteopathy (Table 1).

Treatment interruption and side effects

During medical cannabis treatment, 39 of the 90 participants (43%) reported a treatment interruption (Tables 2 and S5). Twenty-two stopped treatment definitively, and 17 resumed treatment (six continued with the same preparation and dosage, seven continued with the same preparation but a different dosage, four continued with another preparation). The median time from treatment initiation to treatment interruption was eight weeks (IQR 3–32 weeks). The reasons given for the treatment interruption included lack of improvement in 22 patients (56%), side effects in 18 (46%), the need for a gastric tube in 17 cases (44%) preventing the continuation of treatment, and cost considerations in 9 patients (23%, Tables 2 and S5). Side effects were observed in 25 of the 90 participants (28%) and similar in the THC and CBD group. The three most common side effects were tiredness, sedation, and dry mouth (Tables 2 and S5).

Awareness, prescription, and cost modalities

Caregivers learned about medical cannabis therapy through the media (44; 49%), their family doctor or medical specialist (37; 41%), and friends or family members (21; 23%). In most cases (82; 91%), specialist doctors, neuropaediatricians, neurologists, oncologists, or palliative care specialists prescribed the preparation. The cost of the first prescription was reimbursed by the invalidity insurance (insurance covering some chronic diseases such as epilepsy or cerebral palsy) in 50 participants (56%), and the health insurance covered the cost for ten patients (11%, Table 3). For 27 participants (30%), caregivers paid out of their pocket. This situation persisted during the treatment. The monthly cost was below 300 USD for 24 participants (27%), between 301 to 600 USD for 22 (24%), more than 600 USD for 25 (28%). The cost was unknown for the remaining 19 children or adolescents. Many caregivers were concerned about the high cost of medical cannabis preparations. Table S3 gives further details about costs.

Treatment effects of medical cannabis preparations

In 59 of 90 participants (66%), the treatment with medical cannabis was reported to be successful by the caregivers (Tables 2 and S5). Participants treated with THC products most frequently reported a reduction of pain, spasticity, seizures, and a reduction in the number of drugs taken. Participants treated with pure CBD-containing products most commonly reported a reduction in the frequency of seizures. Irrespective of treatment with THC or CBD only, caregivers felt that their children or adolescents were more relaxed, more satisfied, and in better general condition than before the therapy with medical cannabis (Fig. 3, Table S6). The use of other therapies like physiotherapy, osteopathy, speech, or occupational therapy did not change, regardless of whether the patients received THC or CBD only (Fig. 3).

Reported treatment effects of medical cannabis use in children and adolescents from the caregivers’ perspective. The number indicates the number of responses. Detailed results are presented in additional Table 3

Discussion

The use of medical cannabis to treat a variety of diseases among children and adolescents is increasing. We found that THC was most frequently used to treat pain, spasticity, seizures, lack of weight gain, and nausea, while CBD only was used to treat pain, seizures, and sleep disorders. The largest treatment effects were reported for pain, spasticity, and frequency of seizure in participants treated with THC, and for those treated with CBD only, the frequency of seizures. Irrespective of treatment with THC or CBD only, or a preparation containing both, most caregivers felt that their children and adolescents were more relaxed, more satisfied, and had increased quality of life with medical cannabis treatment. The treatment was reported to be successful in two thirds of participants. Treatment interruption was frequent, mainly due to lack of improvement, side effects, or cost considerations.

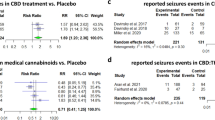

In our study, 80% of participants suffered from a disease of the nervous system. The most common diagnosis was epilepsy, for which 55% of caregivers reported a reduction in seizures and 6% reported seizure aggravation while on medical cannabis. In a similar study examining treatment with cannabidiol-enriched cannabis in children with treatment-resistant epilepsy, 84% of caregivers reported a reduction in the frequency of their children’s seizures [21]. Another retrospective study based on clinical records showed that children with intractable epilepsy treated with CBD-enriched cannabis oil with a 20:1 CBD to THC formulation reported a reduction in the frequency of seizure in almost 90% of children, along with aggravation of seizures in 7% [22]. Beyond observational studies, randomized controlled trials (RCT) were conducted in children with treatment-resistant epilepsy to assess the efficacy and tolerability of CBD compared to placebo. These studies confirmed that CBD reduces seizure frequency [7–10]. A study from Israel showed that epilepsy in children can also be treated with a standardized preparation containing CBD and THC [23]. Finally, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis summarized results from intervention studies and concluded that CBD is more effective than placebo for treatment-resistant epilepsy, regardless of the aetiology of the epileptic syndrome [24].

The second most common indication for the use of medical cannabis was spasticity. Among our participants, 49%, mainly those with cerebral palsy, reported a reduction of spasticity. A case series of 16 children, adolescents or young adults with resistant spasticity in palliative care who received 2.5% dronabinol showed reduced spasticity [25]. An intervention study in children with complex motor disorders treated either with cannabis oil with a 20:1 or 6:1 CBD to THC formulation showed similar improvements in both groups in spasticity, sleep difficulties, pain severity, and quality of life [26]. However, a recent multicentre RCT (2020) in 72 children or adolescents with cerebral palsy or another central nervous system injury after birth found no significant difference in spasticity with a cannabis extract (Nabiximols) and placebo after 12 weeks of treatment (3). Today, the evidence that medical cannabis has an impact on spasticity in children is weak. In adults with multiple sclerosis or paraplegia, a systematic review of RCTs showed some evidence supporting the efficacy of medical cannabis in spasticity [27–30].

he use of medical cannabis in children and adolescents poses risks. Our study found that medical cannabis was prescribed for various conditions, even though the evidence is weak for many. Although there is some evidence in adults supporting the efficacy of medical cannabis for some diseases, we should not extrapolate results from adults to children. Limited evidence exists for the effective use of different cannabis derivatives, dosage, and indications. Indeed, the high rate of treatment interruption or stop (43%) seen in our study was driven by side effects and lack of improvement. Thus, clinicians should closely monitor children and adolescents on medical cannabis for efficacy and adverse effects, and they should be experienced in the treatment of the underlying disease. In addition, potential drug interactions should be considered. A systematic review on safety and efficacy in epilepsy summarized drug–drug interactions of CBD with other drugs metabolized in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes exists. Therefore, treatment with CBD can result in elevated liver enzyme, especially when co-medicated with the antiepileptic drug valproate [31]. However, current evidence is limited about both the interaction of medical cannabis with other drugs. Treatment guidelines are needed to inform decision making by clinicians and caregivers. Although such guidelines are available in a few countries [32–34], they currently do not exist in Switzerland and many other countries. Another reason for stopping treatment was the costs for medical cannabis, which have to be paid out of the caregivers’ pocket. The production of quality-controlled medical cannabis is laborious. The costs for other medical and nonmedical treatments in these children, which will generally be covered by health insurance, might be substantially higher [35].

This is one of the first studies reporting on prescription practices, dosages, and treatment outcomes in a large sample of children and adolescents using medical cannabis in a real-life setting. Two strengths particularly distinguish our study from others. Participants were patients under 18 years of age who received medical cannabis over the entire period since its use was authorised in Switzerland. The pharmacy in Langnau is a pioneer in this field and the largest professional distributor of medical cannabis in Switzerland. Also, even though the dosage of medical cannabis preparations varied, the concentrations were standardized. Other publications and recommendations often lack such standardization, which hampers comparisons across studies.

The most important limitation of our study was the lack of a comparison group. Another limitation derives from the fact that the caregivers reported the data, which may lead to a recall bias. However, it is common in the paediatric field to collect outcome data reported by caregivers, especially in children with disabilities. A further limitation is the potential selection bias arising from group differences between those who participated and those who did not. Participants’ health and the situations of participating families may have been better than those of nonparticipants. How this could have influenced our findings is unknown.

Conclusions

In Switzerland, medical cannabis was mainly prescribed to children and adolescents with neurological diagnoses, particularly epilepsy. Although evidence supporting efficacy is lacking, medical cannabis was prescribed to children and adolescents for various other conditions. For two thirds of participants treated with standardized THC or CBD preparations, the caregiver reported an improvement in their condition and well-being. Others stopped preparations because of lack of effectiveness or side effects. Medical cannabis could be a promising and useful therapy for children and adolescents with neurological conditions. However, we need further RCTs with standardized THC and CBD preparations to assess the efficacy of medical cannabis in different diseases and long-term effects in the young.

Code availability

The collected data and the datasets used for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CBD:

-

Cannabidiol

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- THC:

-

Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol

References

Borgelt LM, Franson KL, Nussbaum AM, Wang GS (2013) The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis. Pharmacotherapy 33(2):195–209

Wong SS, Wilens TE (2017) Medical cannabinoids in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Pediatrics 140(5)

Fairhurst C, Kumar R, Checketts D, Tayo B, Turner S (2020) Efficacy and safety of nabiximols cannabinoid medicine for paediatric spasticity in cerebral palsy or traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Dev Med Child Neurol 62(9):1031–1039

Phillips RS, Friend AJ, Gibson F, Houghton E, Gopaul S, Craig JV et al (2016) Antiemetic medication for prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2(2):Cd007786

Chan HS, Correia JA, MacLeod SM (1987) Nabilone versus prochlorperazine for control of cancer chemotherapy-induced emesis in children: a double-blind, crossover trial. Pediatrics 79(6):946–952

Bergamaschi MM, Queiroz RH, Zuardi AW, Crippa JA (2011) Safety and side effects of cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa constituent. Curr Drug Saf 6(4):237–249

Devinsky O, Patel AD, Cross JH, Villanueva V, Wirrell EC, Privitera M et al (2018) Effect of cannabidiol on drop seizures in the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. New Eng J Med 378(20):1888–1897

Devinsky O, Cross JH, Laux L, Marsh E, Miller I, Nabbout R et al (2017) Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. New Eng J Med 376(21):2011–2020

Devinsky O, Patel AD, Thiele EA, Wong MH, Appleton R, Harden CL et al (2018) Randomized, dose-ranging safety trial of cannabidiol in Dravet syndrome. Neurology 90(14):e1204–e1211

Thiele EA, Marsh ED, French JA, Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska M, Benbadis SR, Joshi C et al (2018) Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England) 391(10125):1085–1096

Bergamaschi MM, Queiroz RH, Chagas MH, de Oliveira DC, De Martinis BS, Kapczinski F et al (2011) Cannabidiol reduces the anxiety induced by simulated public speaking in treatment-naive social phobia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 36(6):1219–1226

Barchel D, Stolar O, De-Haan T, Ziv-Baran T, Saban N, Fuchs DO et al (2019) Oral cannabidiol use in children with autism spectrum disorder to treat related symptoms and co-morbidities. Front Pharmacol 9(1521)

Bar-Lev Schleider L, Mechoulam R, Saban N, Meiri G, Novack V (2019) Real life experience of medical cannabis treatment in autism: analysis of safety and efficacy. Sci Rep 9(1):200

Bundesrat (2018) Cannabis für Schwerkranke: Bericht des Bundesrates in Erfüllung der Motion 14.4164, Kessler, 11.12.2014. Bundesrat

Bundesrat (2020) 812.121 Bundesgesetz vom 3. Oktober 1951 über die Betäubungsmittel und die psychotropen Stoffe (Betäubungsmittelgesetz, BetmG) Bern Bundesrat; Available from: https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/19981989/index.html

Praxis Suchtmedizin Schweiz (2018) CBD St. Gallen Praxis Suchtmedizin Schweiz; Available from: https://praxis-suchtmedizin.ch/praxis-suchtmedizin/index.php/de/cannabis/cbd

Kilcher G, Zwahlen M, Ritter C, Fenner L, Egger M (2017) Medical use of cannabis in Switzerland: analysis of approved exceptional licences. Swiss Med Wkly 147:w14463

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42(2):377–381

Praxis Suchtmedizin Schweiz (2019) Übersicht der gebräuchlichsten Cannabinoide in der Schweiz St.Gallen: Praxis Suchtmedizin Schweiz; Available from: https://www.praxis-suchtmedizin.ch/praxis-suchtmedizin/images/stories/cannabinoide/20191023_praeparate-galenik-hersteller-dosierung-kosten.pdf

Fankhauser M. Kompendium Cannabisprodukte der Bahnhof Apotheke Langnau AG LangnauNA. Available from: https://panakeia.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/Cannabis/1_Kompendium__Cannabispraeparate_.pdf

Porter BE, Jacobson C (2013) Report of a parent survey of cannabidiol-enriched cannabis use in pediatric treatment-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 29(3):574–577

Tzadok M, Uliel-Siboni S, Linder I, Kramer U, Epstein O, Menascu S et al (2016) CBD-enriched medical cannabis for intractable pediatric epilepsy: the current Israeli experience. Seizure 35:41–44

Hausman-Kedem M, Kramer U (2017) Efficacy of medical cannabis for treatment of refractory epilepsy in children and adolescents with emphasis on the Israeli experience. Isr Med Assoc J: IMAJ 19(2):76–78

de Carvalho Reis R, Almeida KJ, da Silva Lopes L, de Melo Mendes CM, Bor-Seng-Shu E (2020) Efficacy and adverse event profile of cannabidiol and medicinal cannabis for treatment-resistant epilepsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav 102:106635

Kuhlen M, Hoell JI, Gagnon G, Balzer S, Oommen PT, Borkhardt A et al (2016) Effective treatment of spasticity using dronabinol in pediatric palliative care. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 20(6):898–903

Libzon S, Bar-Lev Schleider L, Saban N, Levit L, Tamari Y, Linder I et al (2018) Medical Cannabis for Pediatric Moderate to Severe Complex Motor Disorders. J Child Neurol 33:088307381877302

Zajicek J, Fox P, Sanders H, Wright D, Vickery J, Nunn A et al (2003) Cannabinoids for treatment of spasticity and other symptoms related to multiple sclerosis (CAMS study): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet 362(9395):1517–1526

da Rovare VP, Magalhães GPA, Jardini GDA, Beraldo ML, Gameiro MO, Agarwal A et al (2017) Cannabinoids for spasticity due to multiple sclerosis or paraplegia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Complement Ther Med 34:170–185

Wade DT, Makela P, Robson P, House H, Bateman C (2004) Do cannabis-based medicinal extracts have general or specific effects on symptoms in multiple sclerosis? A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study on 160 patients. Mult Scler J 10(4):434–441

Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, Di Nisio M, Duffy S, Hernandez AV et al (2015) Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Jama 313(24):2456–2473

Samanta D (2019) Cannabidiol: A Review of Clinical Efficacy and Safety in Epilepsy. Pediatric neurology 96:24–29

Sundheds- og Ældreministeriet (2017) Vejledning om lægers behandling af patienter med medicinsk cannabis omfattet af forsøgsordningen Copenhagen: Sundheds- og Ældreministeriet; Available from: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/retsinfo/2018/9000

Queensland Health (2018) Clinical Guidance: for the use of medicinal cannabis products in Queensland Queensland: Queensland Health; Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/634163/med-cannabis-clinical-guide.pdf

Therapeutic Goods Administration (2020) Medicinal cannabis - guidance documents Woden ACT: Australian Government Department of Health; Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/node/732373

Riechmann J, Strzelczyk A, Reese JP, Boor R, Stephani U, Langner C et al (2015) Costs of epilepsy and cost-driving factors in children, adolescents, and their caregivers in Germany. Epilepsia 56(9):1388–1397

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the study participants and their caregivers who were willing to share their medical history. We also would like to thank the staff at the pharmacy in Langnau for their assistance in preparing the participants’ list.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Universität Bern. This project was supported by institutional funding from the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Bern. ME is supported by special project funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 189498). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KZ conceptualized and designed the study, developed the questionnaire, coordinated the study, collected, entered, and analysed the data. KZ drafted the initial manuscript and reviewed and revised the manuscript. LF conceptualized and designed the study, developed the questionnaire, coordinated and supervised data collection, helped to draft the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. ME conceptualized and designed the study, helped to draft the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. CD collected, entered, and analysed data and critically reviewed the manuscript for important content. MR entered data and critically reviewed the manuscript for important content. PW, SG, IW, MF, and DE contributed to the development of the questionnaire and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent to participate

The Cantonal Ethics Committee Bern (2019–00,049), Switzerland, approved this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the caregivers of each child or adolescent younger than 14 years. Among older adolescents, either the adolescent or the caregivers gave informed consent.

Consent for publication

Written consent for publication was obtained from the caregivers of each child or adolescent younger than 14 years. Among older adolescents, either the adolescent or the caregivers gave written consent.

Competing interests

MF is the owner of the Bahnhof Apotheke Langnau AG, which produces and distributes medical cannabis-based preparations to patients upon medical prescription. DE works as a pharmacist in the same pharmacy and is a board member of the Swiss Society of Cannabis in Medicine. MF and DE had no role in study design and data analysis. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by Gregorio Paolo Milani

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zürcher, K., Dupont, C., Weber, P. et al. Use and caregiver-reported efficacy of medical cannabis in children and adolescents in Switzerland. Eur J Pediatr 181, 335–347 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04202-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04202-z