Abstract

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum is uncommon in paediatric practice. We describe two cases of spontaneous pneumomediastinum in a child and an adolescent with anorexia nervosa. Thorough investigation failed to reveal any underlying cause for secondary pneumomediastinum. Pneumomediastinum in anorexia nervosa can be caused by not only elevated intrathoracic pressures, but also by the poor quality of the alveolar walls due to malnutrition. The incidence of spontaneous pneumomediastinum in anorexia nervosa is probably higher than that recorded, since it resolves spontaneously and, therefore, it can remain undetected. We conclude that it is our considered opinion that malnutrition associated with anorexia nervosa predisposes for spontaneous pneumomediastinum due to weakness of the alveolar wall and the loss of connective tissue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pneumomediastinum is rarely associated with anorexia nervosa (AN). Approximately 20 cases of pneumomediastinum in anorexia patients are described in the literature. Vomiting, a common symptom in AN, is a known cause of pneumomediastinum [13]. But of the cases reported in the literature, only a few (three) were preceded by vomiting [3, 4, 12]. So, there has to be another cause placing patients with AN at risk for spontaneous pneumomediastinum. We report one case with spontaneous pneumomediastinum as the presenting symptom of AN. In the other case, spontaneous pneumomediastinum is a complication of AN. A review of the literature is given and we discuss the possible pathophysiology of spontaneous pneumomediastinum in patients with AN.

Case report

Case 1

A 13-year-old girl presented with increasing complaints of an unusual crackling sensation and sound in her neck during three days. At that time, she complained of neck pain and headache.

When these complaints started, she had a sore throat with painful swallowing.

Further medical history mentioned a Cooper test, a test of physical fitness, at school two weeks earlier. There had been no trauma or injury and no coughing or vomiting.

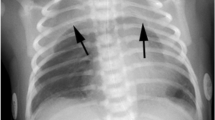

Physical examination showed a respiratory rate of 16 per minute, cardiac rate of 51 per minute, blood pressure of 87/55 mmHg and temperature of 36.5°C. Her height was 150 cm (SD −2), weight 34 kg (SD −1.5) and body mass index (BMI) 15 kg/m2 (SD −2.5). There was a slight bilateral bulging of the skin of her neck from the mandible to both clavicles, with, on palpation, a crackling sensation as a diagnostic sign of subcutaneous emphysema. Apart from being extremely slim, the skin was normal, with no signs of injury. Cardiac evaluation showed normal heart sounds without cardiac murmur. There was no dyspnoea. On auscultation, there was normal bilateral vesicular breathing. Blood tests revealed no abnormalities. Chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) scan revealed mediastinal emphysema with extension to the neck region (Fig. 1). There was no pneumothorax and no extension to the retroperitoneum. An oesophageal gastric passage X-ray was normal, without signs of perforation. Laryngopharyngoscopy did not reveal mucosal lesions or signs of submucosal swelling. Electrocardiography was normal, except bradycardia. After admission to the hospital, she showed loss of appetite and further history revealed an anorectic episode, for which, she had been referred by her general practitioner to a psychologist. At the age of 13 years, she weighed 46 kg, diminishing to 37 kg 4 months later. At the time of admission to the hospital, her weight was 34 kg at the age of 13 years and 6 months. There was absolutely no history of vomiting.

Within a week, the subcutaneous emphysema disappeared. She was referred to an eating disorders clinic to manage her eating disorder. She never showed any signs of purging during treatment and recovered from her AN.

Case 2

A 17-year-old girl with known AN and vomiting presented with extreme malnutrition requiring refeeding. She complained of unusual crackling sensation in her neck during eight days, starting after a choking incident while drinking, followed by coughing. The same day, she felt pressure on her chest. During the following days, her neck became swollen and her voice became hoarse. The swelling had already subsided considerably at the time of presentation.

Physical examination showed an extreme cachectic girl of 17 years with a respiratory rate of 16 per minute, cardiac rate of 64 per minute, blood pressure of 85/55 mmHg and temperature of 36.0°C. Her height was 170 cm (SD=0), weight 34.4 kg (SD<<−2) and BMI 12 kg/m2 (SD<<−2.5).

There were signs of subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and in both arms. She had dry skin without signs of injury. Cardiac auscultation was normal without cardiac murmur. There was no dyspnoea. Pulmonary auscultation was also normal. Blood tests revealed no abnormalities. Chest X-ray and CT scan revealed subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and mediastinal emphysema with extension to the intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal and epidural regions (Fig. 2). There was no pneumothorax.

Laryngopharyngoscopy did not reveal mucosal lesions. The laryngeal mucosa was slightly swollen.

After refeeding, she was referred to an eating disorders clinic to manage her eating disorder.

Within two weeks, the subcutaneous emphysema further resolved spontaneously.

Discussion

Pneumomediastinum, the presence of free air contained within the mediastinum, usually results from spontaneous alveolar wall rupture and, far less commonly, from disruption of the upper airways or gastrointestinal tract [8].

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum can be distinguished from pneumomediastinum secondary to traumatic events, such as chest trauma or thoracic surgery, endobronchial or oesophageal procedures, mechanical ventilation or other invasive procedures [13].

A large and diverse group of factors has been implicated in the development of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Various respiratory manoeuvres that have in common the development of high intrathoracic pressures may lead to pneumomediastinum. These include Valsalva manoeuvres, coughing, vigorous crying and vomiting. The mechanism of development of spontaneous pneumomediastinum was originally described by Macklin and Macklin as increased intra-alveolar pressure causing the rupture of alveoli with the escape of air into the mediastinum. The mediastinum is subsequently decompressed by further passage of the air into the retroperitoneal and subcutaneous spaces (the Macklin effect) [1, 9]. Whereas primary pneumomediastinum is a relatively benign and self-limited disorder, secondary pneumomediastinum due to oesophageal perforation or Boerhaave’s syndrome is a potentially life-threatening disorder because of the inevitable development of mediastinitis. Primary pneumomediastinum rarely requires treatment as the alveolair rupture heals and the leaked air resolves spontaneously. By contrast, secondary pneumomediastinum due to oesophageal perforation often requires surgical intervention [8].

Pneumomediastinum typically manifests as sudden chest pain or dyspnoea and, less commonly, with dysphagia and hoarseness [8]. Our first patient, however, presented with a sore throat, painful swallowing, complaints of pain in the neck and headache. The second patient presented with initial chest pain and hoarseness. The detection of subcutaneous air in the neck and anterior chest wall and Hamman’s sign, a crunching sound synchronous with the heartbeat, are important physical findings. Radiographically, pneumomediastinum manifests on the posteroanterior projection as a thin radiolucent line parallel to the outline of the heart, as the mediastinal pleura is displaced laterally, and on the lateral projection as the accumulation of air retrosternally [8].

When chest pain and dyspnoea occur, panic attacks must be differentiated from pneumomediastinum. Panic disorders are often seen in patients with AN [6]. As a consequence, we believe that pneumomediastinum should be ruled out in anorexia patients presenting with signs of a first panic attack.

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum is rarely associated with AN. Only 21 publications related to this association are reported by Pubmed.

Purging behaviour, such as self-induced vomiting, is common among AN patients. Vomiting is a known cause of pneumomediastinum, placing anorexia patients, who frequently vomit, at risk for pneumomediastinum. However, in only a few of the cases described in the literature was vomiting was the preceding event of the pneumomediastinum. In most reports, like in our patients, pneumomediastinum in anorectic patients is not preceded by vomiting [1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8].

In our patients, the diagnostic procedure did not reveal an oesophageal or upper airway perforation. The pathophysiologic mechanism of air entrance into the mediastinum can be explained by the rupture of an alveolar wall, which is mostly the cause of an air leak into the mediastinum [8]. Based on the literature and our observations, patients with AN are at risk for spontaneous pneumomediastinum, even if they are not vomiting.

We speculate that the state of malnutrition contributes to the risk of spontaneous pneumomediastinum.

Animal studies reveal that calorie restriction causes a loss of alveoli and a fall in gas-exchange tissue [10, 11] and thinner alveolar walls [10]. To survive periods of not eating, organisms sacrifice comparatively non-essential structures for gluconeogenesis to provide glucose for the brain and amino acids to maintain muscle. Because the total organismal and lung oxygen consumption fall during calorie restriction, some lung tissue is expendable [10].

Also in human studies, atrophic changes, such as large alveoli and thin alveolar walls, due to starvation were found in Jewish people in the Warsaw Ghetto [14].

With thinner alveolar walls and the loss of alveoli, malnourished individuals are at risk of alveolar wall rupture.

Since known factors of increased intra-alveolar pressure were absent in our first case and since clinical examination and radiographic study did not reveal an esophageal or upper airway perforation, we must assume that subclinical alveolar leaks with subsequent air dissection, pneumomediastinum and diffuse soft tissue emphysema occurred because of weakness of the alveolar wall and thinning of the connective tissue caused by severe malnutrition. Therefore, even with a minimal increase of intra-alveolar pressure, such as that which may occur during usual daily activities, such as a choking incident, can become the cause of air leaks, as in our second case.

Abbreviations

- AN:

-

anorexia nervosa

References

Al-Mufty NS, Bevan DH (1977) A case of subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum and pneumoretroperitoneum associated with functional anorexia. Br J Clin Pract 31(10):160–161

Altmeyer RB, Morgan EJ (1981) Spontaneous pneumomediastinum as a complication of anorexia nervosa. W V Med J 77(8):189–190

Brooks AP, Martyn C (1979) Pneumomediastinum in anorexia nervosa. Br Med J 1(6156):125

Donley AJ, Kemple TJ (1978) Spontaneous pneumomediastinum complicating anorexia nervosa. Br Med J 2(6152):1604–1605

Fergusson RJ, Shaw TRD, Turnbull CM (1985) Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a complication of anorexia nervosa? Postgrad Med J 61(719):815–817

Godart NT, Flament MF, Lecrubier Y, Jeammet P (2000) Anxiety disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: co-morbidity and chronology of appearance. Eur Psychiatry 15(1):38–45

Hatzitolios AI, Sion ML, Kounanis AD, Toulis EN, Dimitriadis A, Ioannidis I, Ziakas GN (1997) Diffuse soft tissue emphysema as a complication of anorexia nervosa. Postgrad Med J 73(864):662–664

Karim A, Ahmed S, Rossoff L (2003) Pneumomediastinum simulating a panic attack in a patient with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 33(1):104–107

Macklin MT, Macklin CC (1944) Malignant interstitial emphysema of the lungs and mediastinum as an important occult complication in many respiratory diseases and other conditions: An interpretation of the clinical literature in the light of laboratory experiment. Medicine 23:281–352

Massaro D, Massaro GD, Baras A, Hoffman EP, Clerch LB (2004) Calorie-related rapid onset of alveolar loss, regeneration, and changes in mouse lung gene expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286(5):L896–L906

Massaro GD, Radaeva S, Clerch LB, Massaro D (2002) Lung alveoli: endogenous programmed destruction and regeneration. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283(2):L305–L309

Overby KJ, Litt IF (1988) Mediastinal emphysema in an adolescent with anorexia nervosa and self-induced emesis. Pediatrics 81(1):134–136

Schulman A, Fataar S, Van der Spuy JW, Morton PCG, Crosier JH (1982) Air in unusual places: some causes and ramifications of pneumomediastinum. Clin Radiol 33(3):301–306

Winick M (1979) Hunger disease. Studies by the Jewish physicians in the Warsaw Ghetto. Wiley, New York, pp 221–223, 237–254

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Veelen, I., Hogeman, P.H.G., van Elburg, A. et al. Pneumomediastinum: a rare complication of anorexia nervosa in children and adolescents. A case study and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr 167, 171–174 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-007-0444-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-007-0444-9