Abstract

The distinction between serrated polyps of the colon is complex, particularly between hyperplastic polyps (HP) and sessile serrated adenomas (SSA). Recent data show that SSA might be the precursors of serrated colonic cancers, underlining the necessity of identifying them. We characterized the demographic and pathologic characteristics of 102 serrated lesions among 321 polyps of the colorectum and determined if SSA can be microscopically distinguished from HP in biopsy material of a daily practice. There were 81 HP (79%) and 7 SSA (7%) of which one displayed low-grade dysplasia. Only six serrated polyps (6%) could not be correctly classified. The main architectural criteria for distinguishing SSA from HP is the serrated feature along the crypt axis and the rarity of undifferentiated cells in the lower third of the crypts. SSA was significantly more often located in the right colon and larger (median, 11 vs 4 mm) than HP. SSA are rare serrated polyps that can be distinguished from HP based on their morphology, location in the right colon, and larger size. One SSA of our series showed low-grade dysplasia supporting the concept that this lesion might be a precursor of serrated adenocarcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Until recently, serrated non-adenomatous polyps of the colon were diagnosed as hyperplastic polyps (HP) and considered as innocuous and benign lesions without playing a significant role in carcinogenesis [12, 13, 27]. However, over the past several years, serrated polyps have been the focus of morphologic and critical reappraisal.

In 1996, Torlakovic and Snover [25] published a reappraisal of HP occurring in the context of hyperplastic polyposis and proposed that these polyps should be classified as sessile serrated adenomas (SSA). Some authors considered SSA as “aggressive” HP and precursors of serrated colonic cancer [5, 8, 14]. Recently, Snover et al. [23] reported a detailed morphologic and molecular review about serrated polyps of the large intestine and defined morphologic criteria to distinguish HP from SSA. A nomenclature has been proposed by this group but to date there is no consensus for the adoption of an unanimous terminology and classification of SP.

The aim of the current study was to characterize morphologically and demographically a series of serrated polyps focusing particularly on the distinction between SSA and HP. We tested the reproducibility of Snover’s histological criteria of serrated polyps and their applicability in a daily practice, particularly when dealing with SSA, a serrated lesion that should be recognized because of its potential implication in the “serrated neoplasia pathway” [1, 9, 11].

Material and methods

Samples

The biopsy specimens of polyps collected consecutively from November 2005 to January 2006 were provided from the Department of Pathology archives in Lausanne, Switzerland. All the polyps obtained by colonoscopic polypectomy were included in the initial assessment. We retrospectively examined 321 polyps of the large intestine from 200 patients, and 102 serrated polyps were selected from this series. For morphological analysis, all the polyps were sectioned in an identical way, and three levels were routinely examined. All the polyps were examined, including the superficially and tangentially oriented specimen, to have an overview about the reality of a routine and daily practice. The resection of the polyp in one-piece (polypectomy) vs in multiple biopsies was recorded. Microscopic characteristics of the polyps were assessed in a double-headed microscope by two observers involved in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (D.S. and H.B.). The observers were blinded as to the location of the biopsies because knowledge of the site of the polyp might lead to a bias in the interpretation of the histopathologic findings. When there were disagreements between the two observers as to the interpretation of some histologic characteristics and/or classification of a polyp, the case was re-examined and a consensus was obtained. The location, number, and size of the serrated polyps, and the number of samples for each serrated polyp were recorded. The location of colorectal serrated polyps was divided into two groups: right colon (including the splenic flexure) and left colon (descending colon, sigmoid and rectum). The size of the polyps was obtained either from the endoscopist’s measurements or from the macroscopic size of the specimen when the clinician did not mention the measure.

Morphologic classification of polyps

The diagnosis of traditional serrated adenoma (TSA) was based on the criteria established by Longagre and Fenoglio-Preiser [5], combining the serrated glandular pattern of an HP and dysplasia. The Snover’s criteria were used to separate HP from SSA and to subdivide HP into three types according to their amount of mucin (i.e., microvesicular, goblet-cell-rich, and mucin-poor). The diagnosis of mixed serrated polyp was considered if there was an admixture of an adenoma and a serrated polyp. For all serrated polyps, the following histological features were evaluated: location of the serrated appearance (limited to the superficial half of the crypts vs the complete length of the crypts), branching, horizontalization of the crypts (L shaped), dilatation or narrowing of the base of the crypts, and crypt herniation through the muscularis mucosae. Presence of epithelial tufts, foci of pseudostratification of the surface epithelium, cytoplasmic eosinophilia, and dysplasia were also recorded. The different types of crypt cells were assessed (i.e., goblet cells, gastric foveolar, and undifferentiated cells) and scored semi-quantitatively as follows: + if the number was ≤30%, ++ if the number was >30 and ≤60%, and +++ if the number was >60%.

For the second assessment of the serrated polyps, we required, as minimal criteria for the diagnosis of SSA, a serrated pattern throughout the entire length of the crypts and the absence or rarity of undifferentiated cells in the lower third of the crypts. Dilatation of crypts was considered as a minor criterion for the diagnosis of SSA, particularly in tangential or superficial samples, because it was often found in the upper part of the crypts in HP. In poorly orientated or superficial samples, criteria such as branching, herniation, or horizontalization of the crypts could frequently not be assessed. Therefore, we decided to classify a serrated polyp containing more than 30% of undifferentiated cells as HP. If the above-described minimal criteria for diagnosis of SSA could not be assessed in a serrated polyp and if it contained less than 30% undifferentiated cells, then it remained classified as HP vs SSA.

Statistical analysis

Correlations between HP and SSA were assessed using the Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables (sex, site, pseudostratification) and the Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables (age and size). All statistical significance tests were two-tailed, and significance was set at p < 0.05.

Statistical analyses were carried out by means of the software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 14 for PC (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

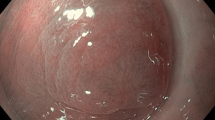

One hundred two (32%) serrated polyps were selected from a series of 321 polyps obtained from 200 patients. Thirty-six biopsies (35%) were superficial (i.e., above the muscularis mucosae) or tangentially oriented, whereas 66 (65%) biopsies were well oriented. Nine polyps were resected in one piece (polypectomy) and 93 polyps in multiple fragments. During the first histologic assessment, the 102 serrated polyps were classified as follows: 58 HP (Fig. 1a,b); 7 SSA (Fig. 2a–d), of which one presented small foci of low-grade dysplasia (Fig. 3); 5 TSA, and 3 mixed polyps (i.e., HP and tubular adenoma). Twenty-nine remaining polyps (28%) were serrated lesions but a more precise diagnosis could not be made on the first histologic review because the biopsy specimens were either small (all measured less than 5 mm) or superficial or tangentially oriented. Moreover, all of them were resected in multiple fragments (between 3–5), rendering the morphologic analysis more difficult. In these cases, the architectural features of either HP or SSA were difficult to be assessed.

After a second review of the 29 not-otherwise-specified serrated lesions (HP vs SSA), 23 serrated polyps were reclassified as HP because the proliferative zone lined by more than 30% of undifferentiated cells was recognizable, even on poorly oriented biopsies. The differential diagnosis between HP and SSA remained unsolved in six cases (6%).

The seven SSA were all resected in one piece, which facilitated the diagnosis, and their morphologic characteristics are detailed in Table 1. In all of them, the crypts were mainly composed of goblet-cell-rich cells with rare or absence of undifferentiated cells. Dilatation, horizontalization, branchment of the crypts, and herniation of the crypts through the muscularis mucosae were often combined in the same lesion in the majority of SSA. Crypt herniation was less frequently seen than branchment or horizontalization. In three SSA, we found that some areas of the polyps were reminiscent of HP, but we did not consider these polyps as mixed serrated polyps because the foci of HP were too small.

Morphological differences between HP and SSA are summarized in Table 2. Branching, L-shaped, and herniation of the crypts are the most useful criteria to distinguish HP from SSA.

There was a statistically significant difference in site and size between HP and SSA (Table 3). HP were preferentially located in the left colon and rectum (n = 60, 74%), whereas most SSA (n = 5, 71%) were located in the right colon (p = 0.002, Fisher exact test). HP were smaller (median, 4 mm) than SSA (median, 11 mm) in a highly significant manner (p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney test). Interestingly, the polyps in the category of indefinite diagnosis (HP/SSA) had the smallest median size (−2.5 mm). There was no significant difference between HP and SSA with regard to age (median, 61 vs 57 years, p = 0.2). The sex ratio was also not statistically different between HP and SSA (p = 0.4).

Discussion

Traditionally, the two principal categories of colorectal polyps have been adenomas and HP. Conventional adenomas are well-identified precursor lesions of the tumor suppressor pathway first proposed by Vogelstein et al. [26]. In contrast, HP have been considered as benign and innocent mucosal lesions for many years, with no involvement in colonic carcinogenesis [12, 13, 27]. However, reassessment of the HP through clinical and epidemiological reports combined with the genetic alterations has led to a reinterpretation of its significance in colorectal carcinogenesis [13, 15]. The serrated polyps demonstrate a “saw-toothed” infolding of the crypt epithelium, probably as a consequence of inhibition of programmed cellular apoptosis of the surface mucosa or more precisely of anoïkis, which is the inhibition of programmed cell exfoliation, leading to prolonged cell life [15]. But to date, no consensus has been established about what classification or nomenclature to use when dealing with serrated polyps. SSA has been described by Torlakovic and Snover in 1996 [25] but has been ignored for several years and designated with different names, rendering this entity quite confusing. Recently, Snover et al. [23] reported an excellent morphologic and molecular review about serrated polyps of the large intestine.

In the present study, we tested the ease of use of this classification on the basis of the described morphological aspects and tried to apply them to the daily practice. We found that the incidence of SSA is very low, as they represent 7% of the serrated polyps and only 2% of all colonic polyps of our series, which is in the range of previously published data [10]. The distinction between HP and SSA was based mainly on architectural features, which seem to be due to abnormal proliferation and probably also decreased apoptosis [24]. These architectural features can be better recognized when a well-oriented polypectomy has been performed. We found that the diagnostic was more difficult when the biopsy specimens were superficial and tangentially cut, when the polyp was addressed fragmented, and when the polyp was small. However, even if the orientation of the biopsy was not optimal, we could distinguish between HP and SSA in the majority of the cases (94%) mainly due to the presence of a great number of undifferentiated cells in the lower third of HP crypts, contrasting with the predominance of goblet or gastric foveolar cells in SSA. Only in six polyps, the differential diagnosis between HP and SSA could not be resolved due to the above-mentioned reasons. The fact that the polyps in the category of indefinite diagnosis (HP/SSA) had the smallest median size (−2.5 vs 4 and 11 mm for the HP and SSA, respectively) appears to indicate that the size of the polyp is an important factor in the distinction of SSA from HP. The smaller the lesion, the more SSA and HP histologically overlap. Intermingling features of HP and SSA in a same serrated polyp, which was observed in three out of seven SSA, might add more difficulty to the distinction between both types of lesions. These findings support the idea that serrated polyps might constitute a continuous spectrum of lesions.

We found that the absence or presence of undifferentiated cells, location of the serration, branchment, horizontalization, and herniation of the crypts appeared to be good discriminators between HP and SSA.

Beside size and morphological features, other parameters seem to be discriminators between HP and SSA. HP are reported to be more frequently located in the distal colon and rectum [3, 6, 10]. Our results are in agreement with these data because we found that the majority of HP were left sided, whereas most SSA were right sided.

For Snover et al. [23], cytological dysplasia is not needed for the diagnosis of SSA, which is in contradiction with the generally accepted consensus about diagnostic criteria in gastrointestinal adenomas. Therefore, some authors do not fully agree with this concept and prefer to label SSA as “atypical HP” or “sessile serrated polyp” [2]. However, in our series, we found one case of SSA showing a low-grade dysplasia, and recently, Goldstein [5] reported eight cases of SSA with incidental high-grade dysplasia or invasive adenocarcinoma. This supports that dysplasia may emerge in SSA and that they are probably precursors of the serrated adenocarcinoma [21]. Molecular studies will probably be able to elucidate the link between morphologic features and molecular changes. Serrated mucosal lesions of the colorectum have emerged as an important concept supporting the existence of an alternate polyp–neoplasia pathway in addition to the classical adenoma–carcinoma sequence [1, 7, 9, 11, 26]. The most common genetic changes seem to be BRAF-activating mutation and CpG island mutation [1, 4, 10, 17, 18, 20, 22]. However, most of the molecular results already published have to be interpreted with caution because the serrated polyps studied were heterogeneous and the diagnostic criteria were poorly defined [4, 6, 17, 19]. To our knowledge, only one recent study analyzed the molecular features of morphologically well-defined serrated polyps of the colorectum [16]. However, molecular studies will be helpful only when a consensual classification will be established to be sure to study specific morphologic sub-types of SP and not a broad range of lesions.

In summary, SSA has clinic and morphologic features distinctive from that of HP. In our view, correct morphologic identification of SSA is essential to enable further studies that are required to assess molecular basis and clinical impact of these lesions.

References

Chan TL, Zhao W, Leung SY, Yuen ST (2003) BRAF and KRAS mutations in colorectal hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas. Cancer Res 63:4878–4881

Cunningham KS, Riddell RH (2006) Serrated mucosal lesions of the colorectum. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 22:48–53

Di Sario JA, Foutch PG, Mai HD (1991) Prevalence and malignant potential of colorectal polyps in asymptomatic, average-risk men. A. J Gastroenterol 86:941–945

Dong SM, Lee EJ, Jeon ES, Park CK, Kim KM (2005) Progressive methylation during the serrated neoplasia pathway of the colorectum. Mod Pathol 18:170–178

Goldstein NS (2006) Small colonic microsatellite unstable adenocarcinomas and high grade epithelial dysplasias in sessile serrated adenoma polypectomy specimen. A study of eight cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1:132–145

Goldstein NS, Bhanot P, Odish E, Hunter S (2003) Hyperplastic-like colon polyps that preceded microsatellite unstable adenocarcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol 119:778–796

Golstein NS (2006) Serrated pathway and APC (conventional)-type colorectal polyps: molecular-morphologic correlations, genetic pathways, and implications for classification. Am J Clin Pathol 1:146–153

Hamilton SR (2001) Origin of colorectal cancers in hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas: another truism bites the dust. J Natl Cancer Inst 5:93.1282–93.1283

Hawkins NJ, Bariol C, Ward RL (2002) The serrated neoplasia pathway. Pathology 34:548–555

Higuchi T, Sugihara K, Jass JR (2005) Demographic and pathological characteristics of serrated polyps of colorectum. Histopathology 47:32–40

Huang CS, O’Brien MJ, Yang S, Farraye FA (2004) Hyperplastic polyps, serrated adenomas and the serrated polyp neoplasia pathway. Am J Gastroenterol 99:2242–2255

Jass JR (2001) Hyperplastic polyps of the colorectum—innocent or guilty? Dis Colon Rectum 44:163–166

Jass JR, Whitehall VL, Young J, Leggett BA (2002) Emerging concepts in colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology 123:862–876

Jass JR (2003) Serrated adenoma of the colorectum. A lesion with teeth. Am J Pathol 162:705–708

Jass JR (2002) Pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Surg Clin North Am 82:891–904

Jass JR, Baker K, Zlobec I, Higuchi T, Barker M, Buchanan D, Young J (2006) Advanced colorectal polyps with the molecular and morphological features of serrated polyps and adenomas: concept of a “fusion” pathway to colorectal cancer. Histopathology 49:121–131

Kambara T, Simms LA, Whitehall VLJ, Spring KJ, Wynter CVA, Walsh MD, Barker MA, Arnold S, McGivern A, Matsubara N, Tanaka N, Higuchi T, Young, Jass JR, Leggett BA (2004) BRAF mutation is associated with DNA methylation in serrated polyps and cancers of the colorectum. Gut 53:1137–1144

Konishi K, Yamochi T, Makino R, Kaneko K, Yamamoto T, Nozawa H, Katagiri A, Ito H, Nakayama K, Ota H, Mitamura K, Imawari M (2004) Molecular differences between sporadic serrated and conventional colorectal adenomas. Clin Cancer Res 10:3082–3090

Lazarus R, Junttila OE, Karttunen TJ, Mäkinen MJ (2005) The risk of metachronous neoplasia in patients with serrated adenoma. Am J Clin Pathol 123:349–359

Lee EJ, Choi C, Park CK, Maeng L, Lee J, Lee A, Kim KM (2005) Tracing origin of serrated adenomas with BRAF and KRAS mutations. Virchows Arch 3:597–602

O’Brien MJ, Yang S, Clebanoff JL, Mulcahy E, Farraye FA, Amorosino M, Swan N (2004) Hyperplastic (serrated) polyps of the colorectum: relationship of CpG island methylator phenotype and K-ras mutation to location and histologic subtype. Am J Surg Pathol 28:423–434

Park SJ, Rashid A, Lee JH, Kim SG, Hamilton SR, Wu TT (2003) Frequent CpG island methylation in serrated adenomas of the colorectum. Am J Pathol 162:815–822

Snover DC, Jass JR, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Batts KP (2005) Serrated polyps of the large intestine. A morphologic and molecular review of an evolving concept. Am J Clin Pathol 124:380–391

Tateyama H, Li W, Takahashi E, Miura Y, Sugiura H, Eimoto T (2002) Apoptosis index and apoptosis—related antigen expression in serrated adenoma of the colorectum0: the saw-toothed structure may be related to inhibition of apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol 26:249–256

Torlakovic E, Snover DC (1996) Serrated adenomatous polyposis in humans. Gastroenterology 110:748–755

Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, Preisinger AC, Leppert M, Nakamura Y, White R, Smits AM, Bos JL (1988) Genetic alterations during colorectal tumor development. N Engl J Med 319:525–532

Wynter CVA, Walsh MD, Higuchi T, Leggett BA, Young J, Jass JR (2004) Methylation patterns define two types of hyperplastic polyp associated with colorectal cancer. Gut 3:573–580

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sandmeier, D., Seelentag, W. & Bouzourene, H. Serrated polyps of the colorectum: is sessile serrated adenoma distinguishable from hyperplastic polyp in a daily practice?. Virchows Arch 450, 613–618 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-007-0413-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-007-0413-8