Abstract

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) play key roles in development. In Drosophila melanogaster, there are three BMP-encoding genes: decapentaplegic (dpp), glass bottom boat (gbb) and screw (scw). dpp and gbb are found in all groups of insects. In contrast, the origin of scw via duplication of an ancestral gbb homologue is more recent, with new evidence placing it within the Diptera. Recent studies show that scw appeared basal to the Schizophora, since scw orthologues exist in aschizan cyclorrhaphan flies. In order to further localise the origin of scw, we have utilised new genomic resources for the nematoceran moth midge Clogmia albipunctata (Psychodidae). We identified the BMP subclass members dpp and gbb from an early embryonic transcriptome and show that their expression patterns in the blastoderm differ considerably from those seen in cyclorrhaphan flies. Further searches of the genome of C. albipunctata were unable to identify a scw-like gbb duplicate, but confirm the presence of dpp and gbb. Our phylogenetic analysis shows these to be clear orthologues of dpp and gbb from other non-cyclorrhaphan insects, with C. albipunctata gbb branching ancestrally to the cyclorrhaphan gbb/scw split. Furthermore, our analysis suggests that scw is absent from all Nematocera, including the Bibionomorpha. We conclude that the gbb/scw duplication occurred between the separation of the lineage leading to Brachycera and the origin of cyclorrhaphan flies 200–150 Ma ago.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Signalling molecules belonging to the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) group perform key roles in morphological and physiological processes in all metazoan phyla. They have been variously referred to as a superfamily or family depending on the author (Newfeld et al. 1999; Van der Zee et al. 2008). Here, we follow a commonly accepted evolutionary definition of family as a set of genes derived from a single gene present in the common ancestor of the bilaterians. Under this classification, we consider the TGFβ grouping as a class formed of two subclasses: bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and the activin/TGFβ subclass (Newfeld et al. 1999). In Drosophila melanogaster, there are two known families of BMP-encoding genes: decapentaplegic (dpp)—a member of the vertebrate BMP2/4 family—as well as glass bottom boat (gbb) and screw (scw)—members of the BMP5/6/7/8 family (Van der Zee et al. 2008). Dpp plays multiple roles in Drosophila development. One of them is its key role in dorso-ventral (DV) patterning during early embryogenesis (Irish and Gelbart 1987). Scw co-operates with Dpp in this process (Arora et al. 1994). Gbb has several roles at later embryonic stages, as well as in larval and pupal development (Doctor et al. 1992; reviewed in O'Connor et al. 2006). It is weakly expressed at early stages and is not involved in DV patterning. It has been proposed that this temporal distinction might separate otherwise functionally redundant proteins (Fritsch et al. 2010).

Several studies have focused on the evolution of BMP-encoding genes in dipterans and other insects (Van der Zee et al. 2008; Fritsch et al. 2010; Lemke et al. 2011). While dpp (BMP2/4) is found in all groups studied so far, there are differences in the number and types of gbb-like genes (BMP5/6/7/8; see Fig. 1, for an overview of the species discussed in the text). The evidence suggests that gbb has undergone multiple duplications in the arthropod lineage, one of which gave rise to scw in the lineage leading to cyclorrhaphan Brachycera (including D. melanogaster; Fritsch et al. 2010). The mosquitoes Anopheles gambiae, Aedes aegypti and Culex pipiens (Culicomorpha) also have two closely related gbb genes, but these duplications appear to have occurred independently in the mosquito lineage (Fritsch et al. 2010). A similar situation applies to the flour beetle Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera) with its two copies of gbb (gbb1 and gbb2), which show distinct expression patterns, but are more closely related to each other than to any other gbb (Van der Zee et al. 2008). Finally, the jewel wasp Nasonia vitripennis (Hymenoptera) also exhibits two gbb-related genes, again more closely related to each other than to any other gbb duplicates. Arthropod species outside the holometabolan insects—such as the water flea Daphnia pulex (Crustacea), the human louse Pediculus humanus (Phthiraptera) and the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum (Hemiptera)—have only one copy of gbb (Fritsch et al. 2010). According to this evidence, arthropods exhibit an ‘ancestral’ gbb (or gbb1) with high sequence conservation across lineages, and a second gbb-like gene in some groups (gbb2 or scw), which arose by independent duplication events. It would be interesting to investigate whether the origin of the scw duplication can be located more precisely within the dipteran lineage.

Schematic tree of organisms discussed in the text. The relationships of the class Insecta are shown including the orders Phthiraptera, Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera and Diptera. The Diptera are traditionally classified into two suborders, the monophyletic Brachycera and an assemblage of basally branching lineages, the Nematocera. The Nematocera include the infraorders Tipulomorpha (not shown), Culicomorpha, Psychodomorpha and Bibionomorpha. The Bibionomorpha are the likely sister group to the Brachycera and together they form the Neodiptera, whose sister group in turn is likely to be the Psychodomorpha. The Brachycera are classified into the infraorders Cyclorrhapha and the basally branching lineages of the non-cyclorrhaphan Brachycera. These include the more closely related infraorders of Asiloidea, Stratiomyomorpha and Tabanomorpha and the likely sister group of the Cyclorrhapha, the Empidoidea. The Cyclorrhapha are in turn divided into the Schizophora with the basally branching lineages of the Cyclorrhapha forming the paraphyletic assemblage of the Aschiza. Previous studies have confirmed the presence of gbb and scw in the Cyclorrhapha (bold lines) indicating the gbb/scw duplication occurred somewhere between the origin of this lineage and the splitting of the Psychodomorpha

Two recent studies have taken the first steps towards this aim. Aschizan cyclorrhaphan species, such as the hoverfly Episyrphus balteatus (Syrphidae), and the scuttle fly Megaselia abdita, have orthologs of dpp, gbb and scw, which show expression patterns similar to the ones in D. melanogaster (Lemke et al. 2011; Rafiqi et al. 2012). This allows us to place the duplication event giving rise to scw at the base of the cyclorrhaphan lineage.

We wanted to further refine the time point of the gbb/scw duplication. No lineages outside the Cyclorrhapha have been shown to have a gbb duplicate identifiable as an orthologue of scw. Here, we describe the BMP gene complement of the moth midge Clogmia albipunctata (Psychodidae). Despite some recent controversy over the placement of Psychodidae (Wiegmann et al. 2011), they are likely to be a sister group of Neodiptera (Brachycera plus Bibionomorpha; Yeates and Wiegmann 1999; Jimenez-Guri et al. 2013). We have found one dpp and one gbb orthologue in C. albipunctata. Using phylogenetic analysis, we have been able to group C. albipunctata dpp and gbb with their orthologues in other lineages. We find that C. albipunctata dpp is a clear member of the dpp gene family, and C. albipunctata gbb branches ancestrally to the cyclorrhaphan gbb/scw split.

Materials and methods

Gene identification and cloning

We searched the early embryonic transcriptome of C. albipunctata (Jimenez-Guri et al. 2013; http://diptex.crg.es) by BLAST using dpp, gbb and scw sequences from D. melanogaster, M. abdita and E. balteatus (retrieved from GenBank). In addition, we searched a preliminary assembly of the C. albipunctata genome (our unpublished data) and the genome of the Hessian fly Mayetiola destructor (Cedidomyiidae, Bibionomorpha; see Fig. 1; genome version 1.0, Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center: http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/content/hessian-fly-genome-project) with these same sequences. PCR primers for C. albipunctata dpp and gbb were designed from transcriptome sequences (dpp-forward CAGTAGAAGGCGTCATAACC, dpp-reverse ACGGAAAAAGAGAGTGAAAAG; gbb-forward ATCTTTATGGCAAAAGGTCTG, gbb-reverse TTTTCGAGACAAAAGAAGAAC). Amplified sequences for C. albipunctata dpp and gbb have been deposited in GenBank (accession numbers KC810051 and KC810052). Fragments were cloned into the PCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and used to make DIG-labelled riboprobes for in situ hybridisation.

Whole mount in situ hybridisation

Wild-type C. albipunctata embryos were collected at blastoderm and post-gastrulation stages as described in García-Solache et al. (2010). Embryos were heat fixed using a protocol adapted from Rafiqi et al. (2011). In situ hybridisation was performed as described in Jimenez-Guri et al. (2013) and references therein.

Phylogenetic analysis

Protein sequences of D. melanogaster Dpp, Gbb and Scw were used to identify and collect homologous sequences using the BLAST algorithm available at NCBI (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The sequences were initially aligned using T-Coffee (Notredame et al. 2000). All subsequent steps (editing, re-alignment, substitution model prediction, phylogenetic analysis and tree visualisation) were carried out using the MEGA5 software (Tamura et al. 2011). Phylogenetic analyses were carried out using a maximum likelihood method and the JTT substitution model and MrBayes allowing model jumping (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001; Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003). Online Resource 1 contains the amino acid alignment used for phylogenetic analysis in FASTA format.

Results and discussion

BMP subclass members in Clogmia include dpp and gbb, but not scw

The evidence described in the ‘Introduction’ section is consistent with the gbb/scw duplication occurring at the base of the Cyclorrhapha. However, it may have happened even earlier, at any time between the divergence of the culicomorph lineage and the emergence of the Cyclorrhapha (Fig. 1). In this study, we narrow the gap between mosquitoes and cyclorrhaphan flies by describing the BMP complement of the moth midge C. albipunctata (Psychodidae), a dipteran species whose lineage branches basally to the Brachycera, and thus Cyclorrhapha (Jimenez-Guri et al. 2013).

We obtained putative BMP members from the transcriptome and genome of C. albipunctata and identified their relationships by reciprocal BLAST searches. We identified single putative orthologues of dpp and gbb/scw from an early embryonic transcriptome (Jimenez-Guri et al. 2013; Diptex database: http://diptex.crg.es, accession numbers comp946 and comp6316). Next, we searched a preliminary genome assembly for C. albipunctata (coverage >70×, scaffold N50 ∼242 kb; our unpublished data). We identified the same single copies of the putative dpp and gbb/scw orthologues. No additional gbb duplicate is present in the genome. At this point, we cannot rule out the possibility that C. albipunctata has lost a scw-like duplicate secondarily.

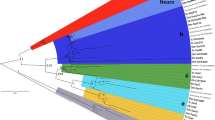

Phylogenetic reconstruction of BMP subclass members in flies

To test our initial classification of these sequences, and to investigate if gene loss played a role in BMP evolution, we carried out a phylogenetic analysis of the putative C. albipunctata dpp and gbb/scw sequences using maximum likelihood methods and Bayesian inference (see ‘Materials and methods’ section). Both approaches yield identical tree topologies (compare Fig. 2 with Online Resource 2). The alignment of the 192 residues used for this phylogenetic analysis can be found in Online Resource 1. Our analysis places C. albipunctata dpp and gbb/scw-like sequences into clades containing dpp and gbb from other lineages (Fig. 2). C. albipunctata dpp clusters with other dipteran dpp sequences, while C. albipunctata gbb branches outside of the cyclorrhaphan gbb/scw group but within the gbb sequences found in other arthropods. This strongly suggests an origin of scw after the psychodid lineage separated from the brachyceran lineage and argues against the possibility of secondary loss of scw in C. albipunctata. Moreover, gbb from the Hessian fly M. destructor (whose lineage, the Bibionomorpha, is the sister group to the Brachycera; see Fig. 1) also branches basally to the cyclorrhaphan gbb/scw group suggesting an origin of scw within the Brachycera.

Phylogenetic analysis of C. albipunctata BMP sequences. The tree is rooted using anti-dorsalizing morphogenetic protein (admp) sequence from the chordate amphioxus (Branchiostoma). Previous analyses have suggested that admp belongs to a family within the BMPs outside of the BMP2/4 and BMP5678 families (Van der Zee et al. 2008). dpp sequences form one group with strong bootstrap support (98), with a second group consisting of gbb, and gbb duplicates, forming another strongly supported group (bootstrap, 100). Within the dpp group, C. albipunctata dpp branches with other dipteran sequences. The second C. albipunctata sequence branches basally to M. destructor gbb, and both branch basally to the cyclorrhaphan gbb/scw genes indicating that they did not take part in this duplication event

Expression patterns of dpp and gbb in C. albipunctata

We visualised the expression patterns of C. albipunctata dpp and gbb during early embryonic development using in situ hybridisation (Fig. 3). C. albipunctata dpp is initially expressed at the blastoderm stage (Fig. 3(a, a′)) and expression persists after gastrulation (Fig. 3(b, b′)). This temporal pattern is similar to that seen in other dipteran species (see St. Johnston and Gelbart 1987; Rafiqi et al. 2012). However, the early spatial expression pattern is very different: instead of a continuous dorsal domain as in D. melanogaster or M. abdita, or a discontinuous dorsal domain to the exclusion of the presumptive serosa as in A. gambiae (Goltsev et al. 2007), C. albipunctata dpp is expressed at the anterior and posterior end of the ventral blastoderm (Fig. 3a). This pattern is very surprising, since ventral dpp expression has not yet been reported in any protostome species. Its implications for DV patterning in C. albipunctata will be analysed and reported elsewhere. Later, in the elongating germ band embryo, C. albipunctata dpp expression pattern is equivalent to that of D. melanogaster or M. abdita (Fig. 3(b, b′)).

In situ hybridisation of BMP transcripts from C. albipunctata. Expression patterns for C. albipunctata dpp (a, a′, b, b′) and gbb (c, c′, d, d′) genes at blastoderm (a, a′, c, c′) and extended germ band stages (b, b′, d, d′). Lateral (a, b, c, d) and ventral (a′, b′, c′, d′) views are shown. Anterior is to the left. See text for a detailed description of expression patterns

In the early blastoderm, C. albipunctata gbb is detected in a very broad central domain, which only excludes two small terminal regions at the poles of the embryo (Fig. 3(c, c′)). This pattern also differs from the expression seen in D. melanogaster, where gbb is not detected before gastrulation (Doctor et al. 1992), or M. abdita, where expression is detected only in the dorsal blastoderm, although it is also excluded from the pole regions (Rafiqi et al. 2012). Similar to the expression in M. abdita and D. melanogaster, we detect C. albipunctata gbb transcript at high levels in a complex, segmentally repeated pattern after gastrulation (Fig. 3(d, d′)).

In conclusion, we identified only two members of the BMP subclass of genes in the psychodid moth midge C. albipunctata: one orthologue of dpp and one gene related to gbb. Their expression patterns at blastoderm stage differ significantly from those seen in Cyclorrapha, while expression during germ band extension is equivalent in both groups. No scw-like gbb duplicate could be identified from the early embryonic transcriptome, or the genome of C. albipunctata, and no such duplicate is present in the genome of the Hessian fly (Bibionomorpha) either. Therefore, our phylogenetic analysis suggests that the gbb/scw duplication occurred within the Brachycera. Further research in non-cyclorrhaphan Brachycera (Empidoidea, Asiloidea, Stratiomyomorpha and Tabanomorpha; Wiegmann et al. 2011; see also Fig. 1) will be required to localise the precise origin of scw within the basal branches of the Brachycera.

References

Arora K, Levine MS, O'Connor MB (1994) The screw gene encodes a ubiquitously expressed member of the TGF-beta family required for specification of dorsal cell fates in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev 8(21):2588–2601

Doctor JS, Jackson PD, Rashka KE, Visalli M, Hoffmann FM (1992) Sequence, biochemical characterization, and developmental expression of a new member of the TGF-beta superfamily in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol 151(2):491–505

Fritsch C, Lanfear R, Ray RP (2010) Rapid evolution of a novel signalling mechanism by concerted duplication and divergence of a BMP ligand and its extracellular modulators. Dev Genes Evol 220(9–10):235–250. doi:10.1007/s00427-010-0341-5, Epub 2010 Nov 18

García-Solache M, Jaeger J, Akam M (2010) A systematic analysis of the gap gene system in the moth midge Clogmia albipunctata. Dev Biol 344(1):306–318. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.04.019, Epub 2010 Apr 28

Goltsev Y, Fuse N, Frasch M, Zinzen RP, Lanzaro G, Levine M (2007) Evolution of the dorsal-ventral patterning network in the mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Development 134(13):2415–2424, Epub 2007 May 23

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F (2001) MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics 17:754–755

Irish VF, Gelbart WM (1987) The decapentaplegic gene is required for dorsal-ventral patterning of the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev 1(8):868–879

Jimenez-Guri E, Huerta-Cepas J, Cozzuto L, Wotton KR, Kang H, Himmelbauer H, Roma G, Gabaldón T, Jaeger J (2013) Comparative transcriptomics of early dipteran development. BMC Genomics 14(1):123

Lemke S, Antonopoulos DA, Meyer F, Domanus MH, Schmidt-Ott U (2011) BMP signaling components in embryonic transcriptomes of the hover fly Episyrphus balteatus (Syrphidae). BMC Genomics 12:278. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-278

Newfeld SJ, Wisotzkey RG, Kumar S (1999) Molecular evolution of a developmental pathway: phylogenetic analyses of transforming growth factor-beta family ligands, receptors and Smad signal transducers. Genetics 152(2):783–795

Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J (2000) T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol 302(1):205–217

O'Connor MB, Umulis D, Othmer HG, Blair SS (2006) Shaping BMP morphogen gradients in the Drosophila embryo and pupal wing. Development 133(2):183–193, Review

Rafiqi AM, Lemke S, Schmidt-Ott U (2011) Megaselia abdita: fixing and devitellinizing embryos. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2011(4):pdb.prot5602. doi:10.1101/pdb.prot5602

Rafiqi AM, Park CH, Kwan CW, Lemke S, Schmidt-Ott U (2012) BMP-dependent serosa and amnion specification in the scuttle fly Megaselia abdita. Development 139(18) :3373–3382. doi:10.1242/dev.083873, Epub 2012 Aug 8

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP (2003) MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19:1572–1574

St Johnston RD, Gelbart WM (1987) Decapentaplegic transcripts are localized along the dorsal-ventral axis of the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J 6(9):2785–2791

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S (2011) MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28(10):2731–2739. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr121, Epub 2011 May 4

Van der Zee M, da Fonseca RN, Roth S (2008) TGFbeta signaling in Tribolium: vertebrate-like components in a beetle. Dev Genes Evol 218(3–4):203–213. doi:10.1007/s00427-007-0179-7, Epub 2008 Apr 8

Wiegmann BM, Trautwein MD, Winkler IS, Barr NB, Kim JW, Lambkin C, Bertone MA, Cassel BK, Bayless KM, Heimberg AM, Wheeler BM, Peterson KJ, Pape T, Sinclair BJ, Skevington JH, Blagoderov V, Caravas J, Kutty SN, Schmidt-Ott U, Kampmeier GE, Thompson FC, Grimaldi DA, Beckenbach AT, Courtney GW, Friedrich M, Meier R, Yeates DK (2011) Episodic radiations in the fly tree of life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(14):5690–5695. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012675108, Epub 2011 Mar 14

Yeates DK, Wiegmann BM (1999) Congruence and controversy: toward a higher-level phylogeny of Diptera. Annu Rev Entomol 44:397–428

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the MEC/EMBL agreement for the EMBL/CRG Research Unit in Systems Biology, by AGAUR SGR grant 406 and by Grants BFU2009-10184 and BFU2009-09168 from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICINN). EJG is supported by ERASysBio+ Grant P#161 (MODHEART). AAC acknowledges the contribution of an internship by the Caixa Catalunya savings bank, which first brought her into contact with the Jaeger lab. Genome and transcriptome sequences used in this study were acquired, assembled and annotated in collaboration with the Genomics and Bioinformatics Core Facilities at the CRG. We thank Brenda Gavilán for the help with maintaining fly cultures.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Claude Desplan

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Online Resource 1

Amino acid alignment used for phylogenetic analysis (FASTA format) (PDF 27 kb)

Online Resource 2

Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of BMP sequences (PDF 5,563 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wotton, K.R., Alcaine Colet, A., Jaeger, J. et al. Evolution and expression of BMP genes in flies. Dev Genes Evol 223, 335–340 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00427-013-0445-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00427-013-0445-9