Abstract

Contrary to what common sense makes us believe, deliberation without attention has recently been suggested to produce better decisions in complex situations than deliberation with attention. Based on differences between cognitive processes of experts and novices, we hypothesized that experts make in fact better decisions after consciously thinking about complex problems whereas novices may benefit from deliberation-without-attention. These hypotheses were confirmed in a study among doctors and medical students. They diagnosed complex and routine problems under three conditions, an immediate-decision condition and two delayed conditions: conscious thought and deliberation-without-attention. Doctors did better with conscious deliberation when problems were complex, whereas reasoning mode did not matter in simple problems. In contrast, deliberation-without-attention improved novices’ decisions, but only in simple problems. Experts benefit from consciously thinking about complex problems; for novices thinking does not help in those cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Imagine that you are a physician and that you are presented with a complex case. The most obvious thing to do would be to think for a while about the case, consider alternative diagnoses, and weigh the evidence in the light of these diagnoses before taking a decision. In this way you would ensure that your decision is the best you can make. Or would it? Not if you accept the findings reported in several studies by Dijksterhuis (2004) and Dijksterhuis, Bos, Nordgren and van Baaren (2006).

Dijksterhuis and colleagues have conducted a series of experiments demonstrating a peculiar phenomenon, the “deliberation-without-attention” effect. When participants in these experiments had to pick the best product out of a collection of products, e.g., the best car among a number of cars presented to them, they were more likely to pick the best one if the investigators prevented them from thinking about their decision by giving them a distraction task. Being allowed to think about their choice, performance was poorer. This only occurred if the choice was sufficiently complex. In simple cases, conscious deliberation helped more than deliberation-without-attention. The investigators’ advice to the readers was therefore to think consciously about simple matters but to delegate thinking about more complex matters to the unconscious.

These findings go against folk wisdom advising us “to think before you act.” They are also surprising because they seem to contradict a long tradition of research showing that being encouraged to think about the solution of a problem usually helps in solving that problem, in particular when the problem is complex (e.g., Alter, Oppenheimer, Epley & Eyre, 2007; Evans, 2008; Kahneman, 2003).

Why would unconscious thinking be superior to more analytic forms of thinking if complex decisions have to be made? Dijksterhuis and colleagues (2006) mention two reasons. The first is that consciousness (here equalized to working memory) has only limited capacity. If the amount of information to be integrated into a decision becomes too large, we would tend to use only a subset of that information, producing suboptimal decisions. The second is that conscious thought can lead to suboptimal weighting of the importance of the various information elements. When objects to be chosen have many attributes, conscious thought would lead to overweight some features in detriment of others, resulting in poorer choices.

We argue here that there may be alternative explanations for Dijksterhuis et al.’s findings. First, methodological shortcomings may be involved. In typical studies (e.g., Dijksterhuis et al., 2006) participants had to choose one from several objects (the best car among different makes of cars) whose attributes were presented in a scrambled fashion. This is hardly how problems present themselves in everyday life and may have added considerably to memory load, possibly favoring pure associative processes. In addition, the attributes were assumed to have similar weight, which is an assumption rarely met in real life. For a family man who travels with several kids, a car with a large trunk may be more important than it is for a man who is not married. Furthermore, an immediate-decision condition was lacking in some studies (e.g., Dijksterhuis et al., 2006). Asking participants to decide immediately after presentation of the material would have enabled them to check whether delayed deliberation without attention actually improves decision-making. These particular experiments, therefore, allowed only for the conclusion that deliberation with attention leads to poorer decision-making. Finally, there was no attempt to control whether the participants were in fact thinking about the problems in the deliberation-with-attention condition. Participants were just asked to think about their choices without any check that they were really doing so.

In addition to these methodological shortcomings, it may be argued that experience with the problem-to-be-solved, a factor not taken into consideration by Dijksterhuis (2004) and Dijksterhuis et al. (2006), crucially influences the quality of deliberation. Participants in their studies were usually novices (e.g., students who had probably never bought a car) without extended knowledge of the domain in which they had to deliberate. A recent study on sports predictions intended to investigate the influence of expertise (Dijksterhuis, Bos, van der Leij & van Baaren, 2009). Participants were again, however, solely students. Furthermore, the way in which expertise was operationalized in this study—as knowledge of a single fact in the domain—hardly represents the expertise of professionals with an extensive knowledge base and experience in solving problems in complex domains.

Second, when the expertise factor is brought into the equation, arguments based on the limited capacity of consciousness seem to lose some of their appeal. This is so because the cognitive structures and processes that experts and novices bring to the task of solving a problem differ. Experts have more relevant knowledge available than students, and this knowledge is better organized and tuned to the task-at-hand. Knowledge in long-term memory provides, once activated, scaffolding for incoming information, thereby evading the working-memory limitations that plague novices (Chi, Feltovich & Glaser, 1981; Ericsson & Kintsch, 1995). If the deliberation-without-attention effect derives from the limitations of consciousness, as Dijksterhuis and colleagues (2006) suggest, it would therefore not necessarily occur in experts’ decision-making. It is known that experienced professionals tend to make choices, usually appropriately, without engaging in conscious analysis of the problem (Norman, 2005; Osman, 2004). What most frequently happens is that an expert recognizes a problem-at-hand as similar to one previously encountered—a process that has been termed “pattern-recognition”—and rapidly retrieves from memory a representation that leads to an appropriate solution (Evans, 2008; Norman & Brooks, 1997; Schmidt, Norman & Boshuizen, 1990). Nevertheless, one may reasonably assume that, if a problem is complex and the solution does not present itself immediately, experts use their extensive knowledge base to consciously seek for a solution. Indeed research has shown that experts may shift from non-analytical to analytical approaches to deal with difficult problems (Osman, 2004; Schmidt & Boshuizen, 1993). Novices on the other hand, with their limited knowledge of the problem, are not expected to profit from conscious search. However, because they suffer from working-memory limitations, they may benefit from deliberation-without-attention.

We tested these ideas in the domain of medicine through an experiment that was designed to overcome the shortcomings of Dijksterhuis et al.’s studies and included medical experts in addition to novices.

Methods

Participants

The participants of the study were 34 internal medicine residents, i.e., physicians in training to become specialists (mean age 28.97; SD 2.25) of a large teaching hospital and 50 fourth-year medical students (mean age 24.00; SD 1.71). All eligible participants were invited to voluntarily participate in the study, and participants received book vouchers in return.

Material and procedure

Participants were asked to diagnose 12 clinical cases (6 complex and 6 simple cases), presented randomly in a booklet. Each case consisted of a description of a patient’s medical history, signs and symptoms, and tests results (Appendix 1 presents an example of a case). Cases were selected from sets of cases used in previous studies (Mamede, Schmidt & Penaforte, 2008; Mamede, Schmidt, Rikers, Penaforte & Coelho-Filho, 2007). The complex cases comprised uncommon diseases, association of diseases, or atypical presentations of a disease. The distinction between complex and simple cases was based on the diagnostic accuracy scores obtained by internal medicine residents in those earlier studies. The list of cases used in the experiment is presented in Appendix 2.

In a within-subjects design, participants diagnosed the cases under three experimental conditions, an immediate-decision condition, and two delayed conditions: conscious thought and deliberation-without-attention. The sequence in which the conditions appeared in the booklet was also randomized. In the immediate-decision condition, participants were asked to read the case and write down the first diagnosis that comes to mind. After that, they solved anagrams, a task added to minimize chances that participants engaged in analytical reasoning under the immediate-decision condition. Following Dijksterhuis et al. (2006), in the unconscious thought condition participants were first informed that they would diagnose the case later on, then read the case, solved anagrams and finally they were asked to formulate a diagnosis. In the conscious thought condition, participants were first requested to read the case and provide an initial diagnosis. They subsequently followed instructions (Mamede et al., 2008) intended to induce an elaborate analysis of case information: they had to indicate which signs and symptoms from the case corroborated or refuted their initial hypothesis, had to write down at least one alternative hypothesis and had to proceed with a similar analysis for each alternative diagnosis. After this analysis, they indicated the likelihood of the several hypotheses and made their final decision on the diagnosis. Four cases (2 simple and 2 complex) were diagnosed under each experimental condition. Time allocated to work on each case was 8 min and equal in all conditions. The importance of taking the anagram task seriously and the restricted time for that were emphasized as an attempt to minimize a possible carry-over effect (i.e., the possibility that participants would continue to reason analytically while solving problems under the other conditions after having diagnosed a case in the conscious thought condition).

Analysis

All cases were based on real patients and had a confirmed diagnosis, against which the accuracy of the participants’ responses was judged. Two experts (board certified experts in internal medicine) independently assessed the diagnoses provided by the participants. The diagnoses were judged correct, partially correct or incorrect, scored respectively 1, 0.5 or 0. The judges were unaware of the condition in which the cases had been diagnosed and agreed in 84% of their judgments. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

The mean diagnostic accuracy scores for complex and simple cases solved by each participant under each experimental condition were calculated, and the mean score for each condition was computed for students and residents. As the data showed a skewed distribution, we performed square-root transformation using the raw scores. Mean diagnostic accuracy scores were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA), with level of expertise (expert versus novice) as a between-subject factor, and case complexity (complex vs. simple cases) and reasoning mode (immediate decision vs. deliberation-without-attention vs. conscious deliberation) as within-subjects factors. Effect size was computed for main effects and interactions and post hoc paired t tests were performed for comparisons across conditions within the groups of doctors and students. For the conscious thought condition, we computed the mean diagnostic scores for the initial diagnoses made by the participants and for the final diagnosis provided after they had consciously analyzed the case. T tests were performed for analyzing differences between these two conditions.

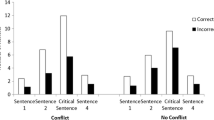

Results

Mean diagnostic accuracy scores for cases diagnosed by the physicians and the students in each condition are presented in Figs. 1 and 2 respectively. There was a significant main effect of case complexity (F(1,83) = 219.26, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.73), validating our distinction between complex and simple cases, and a significant main effect of level of expertise (F(1,83) = 1118.84, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.93), with doctors performing better than students in all experimental conditions, which is also a manipulation check. The two-way interaction effect between reasoning mode and level of expertise (F(2,82) = 4.993, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.06) was significant. The other two-way interactions did not reach significance. The three-way interaction effect (F(2,82) = 3.35, p < 0.04, partial η 2 = 0.04) was significant.

Conscious deliberation led physicians to make better diagnoses in complex cases in comparison with both immediate decision-making (t(33) = 2.86, p < 0.008) and unconscious deliberation (t(33) = 3.12, p < 0.005). No differences were found between the immediate decision and the unconscious deliberation condition (t(33) = 0.67, p < 0.51). In the conscious thought condition, participants were first requested to give an initial diagnosis and, after thoroughly analyzing findings in the case, make a final diagnostic decision. The final diagnoses made by physicians after consciously thinking about the complex cases (M 0.58; SD 0.27) were significantly better (t(33) = 3.00, p < 0.01) than their initial diagnoses (M 0.45; SD 0.33). When diagnosing simple cases, the accuracy of physicians’ decisions did not significantly differ across the three experimental conditions.

The students, however, performed differently. No significant differences were found between diagnoses made through immediate decision and unconscious deliberation for complex cases (t(33) = 0.67, p < 0.55). Consciously thinking to diagnose complex cases led students to poorer decisions then when they made a diagnosis immediately (t(33) = 2.08, p < 0.05). However, when cases were simple, unconscious deliberation led students to perform significantly better than when they made immediate decisions (t(33) = 2.28, p < 0.03). A marginal effect was found between conscious deliberation and immediate decision (t(33) = 1.69, p = 0.10). No effect emerged between conscious thought and unconscious thought (t(33) = 0.52, p = 0.61). Finally, within the conscious-deliberation condition, and only for complex cases and for physicians, a significant effect was found between initial diagnosis and final diagnosis: t(33) = 3.00, p < 0.006.

Discussion

Our findings differ considerably from those reported by Dijksterhuis et al. (2006, 2009). In experts, conscious deliberation was superior to unconscious deliberation and in line with our hypothesis the effect was strongest for complex cases. Dijksterhuis and colleagues found conscious deliberation to be poorer for complex cases. We found the opposite. For simple cases, reasoning mode did not affect experts’ decisions, again differently from their findings. Among students, mode of reasoning did not make a difference, as long as the participants were required to delay their response. Interestingly, among students and with complex cases, performance became poorer when allowed think about the decision. For simple cases, we found a deliberation-without-attention effect, but only when that treatment was compared with the immediate-decision condition.

We offer here an alternative explanation for both our findings and those of Dijksterhuis and colleagues. We distinguish between two cognitive processes that may underlie diagnostic decision-making. The first is a fast pattern-recognition process in which the cues of a case are associatively matched against a pattern in memory (Moors & De Houwer, 2006; Norman & Brooks, 1997; Schmidt & Boshuizen, 1993). The second is a more elaborate, knowledge-based reasoning process, in which problem-solvers consciously activate relevant knowledge until the problem is understood in terms of its underlying structure (Rikers, Schmidt & Boshuizen, 2002; Stanovich & West, 2000). This distinction between pattern-recognition processes and analytical reasoning is in line with dual-process theories of reasoning and judgment (Evans, 2008; Sloman, 1996). In addition, we argue that a real difficulty often involved in diagnostic reasoning is to overcome the influence of salient, seductive cues that may lead one down the garden path. An example may clarify this. Most physicians, confronted with a patient having a history of coronary disease and high cholesterol levels, with severe pain behind the chest bone, would immediately consider a diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. This fast, similarity-based, diagnostic approach leads to accurate decisions in routine situations and is viewed as an efficient strategy developed with experience (Norman, 2005; Norman & Eva, 2010; Schmidt & Rikers, 2007). Nevertheless, this approach may also fail (Elstein, 2009; Graber, Franklin & Gordon, 2005). When this initial diagnosis is wrong, it can only be “repaired” by further conscious analysis of the other, less salient features of the case, leading to the activation of alternative hypotheses and, eventually, recognition of the correct diagnosis. This process of conscious thinking about the case often requires the mobilization of deep, causal knowledge that helps integrate the salient cues with the less obvious ones into a new and better diagnosis, or to discard the salient cues as irrelevant. Doctors often have trouble overcoming the seduction of salient cues, for instance because they use shortcuts to quick decisions or because of premature closure, making it the number-one reason for diagnostic error (Graber et al., 2005; Klein, 2005; Redelmeier, 2005). How do these considerations relate to our experiment?

We assume that responses to the immediate-decision condition were dominated by pattern recognition, whereas the conscious-thinking condition induced the more analytical reasoning process. Let’s first look at the effect of conscious, analytical reasoning on complex cases. Among doctors, the activation of additional relevant knowledge led to a sizable effect over the immediate-decision condition. In fact, consciously thinking about the problem led to a 50% gain in diagnostic accuracy! The validity of this effect of overcoming initial bias was further strengthened because we were able to show that, within the conscious-thinking condition, doctors were very well able to recover from an initially wrong diagnosis as witnessed by the difference between initial and final diagnosis. In line with the so-called default-interventionist form of dual process theories, a rapid intuitive judgment was apparently repaired by effortful analytical reasoning (Evans, 2008). Among students, conscious reasoning had a reverse effect. Their initial diagnosis, although already poor, became worse when they were allowed to think consciously about it and considered alternatives. Since these students had little and largely incorrect knowledge about these complex cases to begin with (as witnessed by their already poor performance in the immediate-decision condition), this suggests that the additional activation of that little knowledge apparently only confused them further by increasing the number of incorrect diagnoses to choose from.

Consciously deliberating about the simple cases displayed a very different pattern. Since the fast, pattern-recognition response in doctors already generated a correct diagnosis in most cases, nothing was gained by further analysis. Hence no differences arose. However, students profited from further analysis, suggesting that sufficient knowledge was available to diagnose these easy cases but this knowledge had to be activated first in order to help students overcome initial bias produced by salient cues, similar to what happened to the doctors confronted with complex cases.

What role is there to play for deliberation-without-attention in diagnostic decision-making? A limited one, it seems. In most conditions, there was no significant difference with the immediate-decision response, similarly to what has been shown in other recent studies (Newel, Wong, Cheung & Rakow, 2009; Rey, Goldstein & Perruchet, 2009), suggesting that unconscious thinking did not really facilitate problem solving. There seems to be, nevertheless, instances in which it helps. In our study, only in students confronted with easy cases there was an effect of deliberation-without-attention. Based on Dijksterhuis et al.’s (2006) assumption that unconscious thinking allows for an associative process in which all cues are weighted equally, one may assume the following: the students had sufficient knowledge to solve these simple cases, but were initially seduced to some extent by some salient (and irrelevant) cues. The associative process postulated by Dijksterhuis and colleagues may have weakened the influence of the salient cues, allowing other cues to equally influence the diagnostic decision. Hence a better performance.

Our explanation for the findings is to some extent speculative, as further research is required to provide additional information on the nature of errors committed under the various conditions. We investigated diagnostic decisions under experimental conditions, which may restrict generalization to real settings and to other types of decisions. The conscious thought condition in our study comprised an elaborate, structured approach to analyze case features, and it may be argued that this helps more than the deliberation-with-attention condition in Dijkterhuis et al.’s (2006, 2009) studies. On the other hand, it allowed checking whether participants were in fact thinking about the case. Furthermore, one may reasonably argue that the procedure closely replicates how doctors reason while thoroughly analyzing a patient’s problem.

A more accurate picture of decision-making seems to be drawn, when expertise is taken into account and problems replicate real situations encountered in professional life in complex domains. In line with recent studies (Acker, 2008; Lassiter, Lindberg, González-Vallejo, Bellezza & Phillips, 2009), our findings cast doubts on the statement that unconscious thought is the superior mode of making complex decisions. Experts confronted with complex problems can make better decisions after consciously thinking about their choices, which is a conclusion with significant implications for (clinical) practice. If one does not have knowledge in a domain, then relying on immediate decisions would be a wiser choice for solving complex problems. Deliberation-without-attention apparently only helps beginners faced with simple problems.

References

Acker, F. (2008). New findings on unconscious versus conscious thought in decision making: Additional empirical data and meta- analysis. Judgment and Decision Making, 3, 292–303.

Alter, A. L., Oppenheimer, D. M., Epley, N., & Eyre, R. N. (2007). Overcoming intuition: Metacognitive difficulty activates analytic reasoning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 136, 569–576.

Chi, M. T. H., Feltovich, P. J., & Glaser, R. (1981). Categorization and representation of physics problems by experts and novices. Cognitive Science, 5, 121–152.

Dijksterhuis, A. (2004). Think different: The merits of unconscious thought in preference development and decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 586–598.

Dijksterhuis, A., Bos, M. W., Nordgren, L. F., & van Baaren, R. B. (2006). On making the right choice: The deliberation-without-attention effect. Science, 311, 1005–1007.

Dijksterhuis, A., Bos, M. W., van der Leij, A., & van Baaren, R. B. (2009). Predicting soccer matches after unconscious and conscious thought as a function of expertise. Psychological Science, 20, 1381–1387.

Elstein, A. S. (2009). Thinking about diagnostic thinking: A 30-year perspective. Advances in Health Sciences Education Theory and Practice, 14, 7–18.

Ericsson, K. A., & Kintsch, W. (1995). Long-term working memory. Psychological Review, 102, 211–245.

Evans, J. St. B. T. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 255–278.

Graber, M. L., Franklin, N., & Gordon, R. (2005). Diagnostic errors in internal medicine. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165, 1493–1499.

Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality. American Psychologist, 58, 697–720.

Klein, J. G. (2005). Five pitfalls in decisions about diagnosis, prescribing. British Medical Journal, 330, 781–783.

Lassiter, G. D., Lindberg, M. J., González-Vallejo, C., Bellezza, F. S., & Phillips, N. D. (2009). The deliberation-without-attention effect: Evidence for an artifactual interpretation. Psychological Science, 20, 671–675.

Mamede, S., Schmidt, H. G., & Penaforte, J. C. (2008). Effects of reflective practice on the accuracy of medical diagnoses. Medical Education, 42, 468–475.

Mamede, S., Schmidt, H. G., Rikers, R. M. J. P., Penaforte, J. C., & Coelho-Filho, J. M. (2007). Breaking down automaticity: Case ambiguity and shift to reflective approaches in clinical reasoning. Medical Education, 41, 1185–1192.

Moors, A., & De Houwer, J. (2006). Automaticity: A theoretical and conceptual analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 297–326.

Newell, B. R., Wong, K. Y., Cheung, J. C. H., & Rakow, T. (2009). Think, blink or sleep on it? The impact of modes of thought on complex decision making. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62, 707–732.

Norman, G. R. (2005). Research in clinical reasoning: Past history and current trends. Medical Education, 39, 418–427.

Norman, G. R., & Brooks, L. R. (1997). The non-analytical basis of clinical reasoning. Advances in Health Sciences Education Theory and Practice, 2, 173–184.

Norman, G. R., & Eva, K. W. (2010). Diagnostic error and clinical reasoning. Medical Education, 44, 94–100.

Osman, M. (2004). An evaluation of dual-process theories of reasoning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 11, 988–1010.

Redelmeier, D. A. (2005). The cognitive psychology of missed diagnoses. Annals of Internal Medicine, 142, 115–120.

Rey, A., Goldstein, R. M., & Perruchet, P. (2009). Does unconscious thought improve complex decision making? Psychological Research, 73, 372–379.

Rikers, R. M. J. P., Schmidt, H. G., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (2002). On the constraints of encapsulated knowledge: Clinical case representations by medical experts and subexperts. Cognition and Instruction, 20, 27–45.

Schmidt, H. G., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (1993). On acquiring expertise in medicine. Educational Psychology Review, 5, 1–17.

Schmidt, H. G., Norman, G. R., & Boshuizen, H. P. (1990). A cognitive perspective on medical expertise: Theory and implication. Academic Medicine, 65, 611–621.

Schmidt, H. G., & Rikers, R. M. J. P. (2007). How expertise develops in medicine: Knowledge encapsulation and illness script formation. Medical Education, 41(12), 1133–1139.

Sloman, S. A. (1996). The empirical case for two systems of reasoning. Psychological Bull, 119, 3–22.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (2000). Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 645–726.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Júlio C. Penaforte and Prof. Dr. João Macedo Coelho-Filho for their permission to use the clinical cases prepared for previous studies. This study was supported by a grant from Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

A 63-year-old male arrives at the emergency room with intense precordial pain and sweating. He has had a history of coronary disease and was admitted to hospital 2 years ago due to a posterior wall myocardial infarction. For the past 30 years the patient has had moderately controlled hypertension. The patient has type II diabetes mellitus and has a history of smoking. He has a family history of heart disease.

The patient has had effort angina that disappeared with sublingual nitroglycerin (NGT) and rest, without changing patterns over the last 30 days. Four hours before presenting to the hospital, the patient was lifting a 22-kg bag of fertilizer when he suddenly felt intense non-radiating precordial pain, along with sweating, nausea and a feeling as if he would faint. He used sublingual nitroglycerin but it did not help to relieve the pain.

Physical examination shows a sweating patient with complaints of pain in the left hemithorax, now radiating to the neck and the interscapular area. BP: 80/40 mmHg; pulse: 110/min; respiratory rate: 24/min. Heart: normal S1 and S2 sounds, S4 gallop sound, diastolic murmur (grade 3/6) more intense at the left sternal border. Lungs: basal crepitations in both lung fields. Abdomen: soft, without signs of peritoneal irritation; no palpable masses. Peripheral pulses: right radial pulse: 1/4; left radial pulse: 4/4; right and left femoral pulses: 3/4, symmetrical.

Diagnosis: aortic dissection.

Appendix 2

List of cases used in the study.

Simple cases

-

1.

Aortic dissection

-

2.

Acute viral hepatitis

-

3.

Hyperthyroidism

-

4.

Acute alcoholic pancreatitis

-

5.

Liver cirrhosis

-

6.

Acute viral pericarditis

Complex cases

-

7.

Small cell lung cancer

-

8.

Sarcoidosis

-

9.

Addison disease with tuberculosis

-

10.

Pneumonia with sepsis

-

11.

Claudication due to occlusive arterial disease

-

12.

Acute bacterial endocarditis

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mamede, S., Schmidt, H.G., Rikers, R.M.J.P. et al. Conscious thought beats deliberation without attention in diagnostic decision-making: at least when you are an expert. Psychological Research 74, 586–592 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-010-0281-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-010-0281-8