Abstract

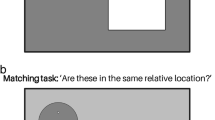

The presupposed advantage of symmetrical objects over asymmetrical objects was investigated in an object matching task, using accidental and non-accidental viewpoints. In addition, the accidental views could be symmetric or asymmetric. When two non-accidental views were presented, symmetrical objects were matched faster than asymmetrical objects. When an accidental view was presented first (followed by a non-accidental view), the matching of symmetrical objects was equal to that of asymmetrical objects. When a non-accidental view was presented first (followed by an accidental view), matching was again equal for the symmetrical and asymmetrical objects, although much faster compared with the opposite sequence of presented views. No effects of image symmetry in the accidental viewpoints were found. Apparently, the advantage of symmetrical objects over asymmetrical objects is only present in object matching when 3-D object structures are visible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It has been argued that there is a preferred, or canonical, view for the recognition of objects (Palmer, Rosche, & Chase, 1981). Palmer et al. define an object’s canonical view as “the view that reveals the most information of greatest salience about it.” However, although a person may have a strong intuition as to what the canonical view might be for any given object, this cannot be easily generalized across objects. In the study by Palmer et al., most objects were preferably viewed from slightly above, with both the front and the side of the objects clearly visible. Similar results were found by Verfaillie and Boutsen (1995). Even though the canonical views used here might not be the best possible views of the objects, the term C-view is used to contrast it with the term A-view

References

Bar, M. (2001) Viewpoint dependency in visual object recognition does not necessarily imply viewer-centered representation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 13, 793–799.

Barlow, H. B., & Reeves, B. C. (1979). The versatility and absolute efficiency of detecting mirror symmetry in random dot displays. Vision Research, 19, 783–793.

Baylis, G. C., & Driver, J. (1994). Parallel computation of symmetry but not repetition within single visual shapes. Visual Cognition, 1, 377–400.

Jolicoeur, P., Corballis, M., & Lawson, R. (1998). The influence of perceived rotary motion on the recognition of objects. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 5, 140–146.

Kahn, J. I., & Foster, D. H. (1986). Horizontal–vertical structure in the visual comparison of rigidly transformed patterns. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 12, 422–433.

Large, M., McMullen, P. A., & Hamm, J. P. (2003). The role of axes of elongation and symmetry in rotated object naming. Perception and Psychophysics, 65, 1–19.

Lawson, R. (1999). Achieving visual object constancy across plane rotation and depth rotation. Acta Psychologica, 102, 221–245.

Lawson, R., & Humphreys, G. W. (1998). View-specific effects of depth rotations and foreshortening on the initial recognition and priming of familiar objects. Perception and Psychophysics, 60, 1052–1066.

Mach, E. (1886). Beiträge zur Analyze der Empfindungen. Jena, Germany: Fisher.

McMullen, P. A., & Farah, M. J. (1991). Viewer-centered and object-centered representations in the recognition of naturalistic line drawings. Psychological Science, 2, 275–277.

Palmer, S. E., & Hemenway, K. (1978). Orientation and symmetry: Effects of multiple, rotational, and near symmetries. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 4, 691–702.

Palmer, S. E., Rosch, E., & Chase, P. (1981). Canonical perspective and the perception of objects. In J. Long & A. Baddeley (Eds.), Attention and Performance IX. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rock, I., & Leaman, R. (1963). An experimental analysis of visual symmetry. Acta Psychologica, 21, 171–183.

Tarr, M. J., & Pinker, S. (1990). When does human object recognition use a viewer-centered reference frame? Psychological Science, 1, 253–256.

Troje, N. F., & Bülthoff, H. H. (1996). Face recognition under varying poses: The role of texture and shape. Vision Research, 36, 1761–1771.

Van der Helm, P. A., & Leeuwenberg, E. L. J. (1996). Goodness of visual regularities: A nontransformational approach. Psychological Review, 103, 429–456.

Van Lier, R. J., & Wagemans, J. (1999). From images to objects: Global and local completions of self-occluded parts. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 25, 1721–1741.

Verfaillie, K., & Boutsen, L. (1995). A corpus of 714 full-color images of depth-rotated objects. Perception and Psychophysics, 57, 925–961.

Vetter, T., & Poggio, T. (1994). Symmetric 3D objects are an easy case for 2D object recognition. Spatial Vision, 8, 443–453.

Wagemans, J. (1995). Detection of visual symmetries. Spatial Vision, 9, 9–32.

Wenderoth, P. (1995). The role of pattern outline in bilateral symmetry detection with briefly flashed dot patterns. Spatial Vision, 9, 57–77.

Willems, B., & Wagemans, J. (2001). Matching multicomponent objects from different viewpoints: Mental rotation as normalization? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27, 1090–1115.

Wilson, K. D., & Farah, M. J. (2003). When does the visual system use viewpoint-invariant representations during recognition? Cognitive Brain Research, 16, 399–415.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted at the Nijmegen Institute for Cognition and Information. Rob van Lier received a grant from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. The authors would like to thank three anonymous reviewers, as well as Peter van der Helm and Tessa de Wit for their helpful comments and suggestions on a previous draft of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koning, A., van Lier, R. No symmetry advantage when object matching involves accidental viewpoints. Psychological Research 70, 52–58 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-004-0191-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-004-0191-8