Abstract

So-called pharmacoresistant (R-type) voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are structurally only partially characterized. Most of them are encoded by the CACNA1E gene and are expressed as different Cav2.3 splice variants (variant Cav2.3a to Cav2.3e or f) as the ion conducting subunit. So far, no inherited disease is known for the CACNA1E gene but recently spontaneous mutations leading to early death were identified, which will be brought into focus. In addition, a short historical overview may highlight the development to understand that upregulation during aging, easier activation by spontaneous mutations or lack of bioavailable inorganic cations (Zn2+ and Cu2+) may lead to similar pathologies caused by cellular overexcitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the human gene of the pharmacoresistant Cav2.3/R-type calcium channel, de novo pathogenic mutations were detected in a group of 30 individuals with developmental and epileptic encephalopathies [13]. The publication represents the first comprehensive investigation in humans with structural variations in this widely expressed voltage-gated calcium channel, together with two earlier reports, in which single cases were mentioned [4, 6].

Based on a short historical overview for the performed basic research, the path and the reasons for an improved understanding of the reported human mutations will be described. Interestingly, most of the channel mutations cluster within the cytoplasmic ends of the four S6 transmembrane segments (Fig. 1), which constitute part of the Cav2.3-channel activation gate.

Alignment of the cytoplasmic parts from the Cav2.3 S6 segments including 11 out of 14 identified disease-causing missense mutations, GenBank L27745.2 (inspired by Fig. 1 and Fig. S3 in Helbig et al., 2018). Note that for the mutants identified in domain II, recombinant studies have shown that the distal part of Cav2.3 is important for the stability of the open state of Cav2.3 [32]. Further, the first evidence for a strong electromechanical coupling between S4–S5 and the S6 of domain II came from a double mutant cycle analysis of the human Cav2.3 confirming the hypothesis that leucine-596 in the IIS4–S5 linker couples strongly to the distal residues in IIS6 (L A I A V D) labelled in bold in this figure [40]. Three out of 30 mutations were located in IS5 (L228P), IIS4-5 (I603L) and IIIS6-IVS1 (G1430N)

“Activation gate” as a functional domain in voltage-gated ion channels

Ion channels represent transmembrane proteins, which are linked by their special structure and gating properties to many physiological functions, including cardiac and neuronal excitability. Ion channels can be either open or closed, and they contain structural elements, which are connected to the transition between these two states. The word “gate” is used to describe this concept, and “gating” is the process whereby the gate is opened and closed [1].

Ligand-gated and voltage-gated channels are activated by different processes but may both include the movement of some internal parts of the molecule to produce an effect in a different part of it to open the permanent pathway permitting the movement of ions. The cytoplasmic parts from the Cav2.3 S6 segments (Fig. 1) represent at least the major “internal part” of the molecule, which causes activation of the channel to open it properly and precisely.

Much more is known by crystallography and mutational analyses about the structural details, which help to convert electrical signals generated by small ion currents across cell membranes to tune all rapid processes in biology and especially in voltage-gated Ca2+ and Na+ channels [8]. These channels contain a tetramer of membrane-bound domains including a positively charged S4 segment. Voltage-dependent activation drives the outward movements of these positive gating changes in the voltage sensor via a “sliding-helix mechanism”, which leads to a conformational change in the pore module that opens its intracellular activation gate (for further details related to the “chemical basis for electrical signalling”, see [8]).

Another recent review specializes on the Cav1.2/L-type Ca2+ channel, which is important for the plateau of the cardiac action potentials, muscle contractions, generation of pacemaker potentials, release of hormones and neurotransmitters, sensory functions and regulated gene expression [14]. Based on gating studies using biophysical and pharmacological studies as well as mathematical simulations, the role of voltage sensors in channel opening was analysed. The gating process is determined by distinct sub-processes, the movements of the voltage-sensing domains (the charged S4 segments) and the opening and closure of S6 gates (for further details related to the individual transitions during activation, see [14]).

The first structural details for the potential coupling between voltage sensors and the pore region came from the crystals of K+ channels [10]. The question arose: how the movement of the S4 segment is transmitted to the S6 helix to open the gate upon depolarization? In the electromechanical coupling model designed for the Kv1.2 channel [20], the S4-S5 linker was located within atomic proximity (4–5 A) of the S6 helix. Thus, it may interact with the latter in the closed state of the channel and was confirmed by double mutant cycle analysis for the expressed human Cav2.3 channel (for further details, see [40]).

History – detection of R-type and “E-type” voltage-gated calcium channels (Tab. 1)

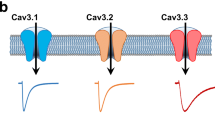

R-type (or initially called “E-type” [33]) Ca2+ channels were identified as the second last member of the group of high-voltage activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels [29]. They are divided into two subfamilies, (i) the L-type channels containing Cav1.1-, Cav1.2-, Cav1.3- and Cav1.4-α1 subunits as the ion-conducting pore and (ii) the non-L-type channels containing Cav2.1(P-/Q-type)-, Cav2.2(N-type)- and Cav2.3(R-type)-α1 subunits as the proteins containing the ion-conducting pore. Low-voltage activated (LVA) Ca2+ channels were structurally defined later by in silico cloning [28, 30] and contain the α1 subunits of T-type channels (Cav3.1-, Cav3.2- and Cav3.3--1) [42] with less homology to two former subfamilies Cav1 and Cav2. The ion-conducting subunit may be in most cases associated with a set of auxiliary subunits [9] and additional interaction partners as proteins binding to cytosolic loops or competing with auxiliary subunits [16, 17]. Within the native environment, they may typically function in the context of macromolecular signalling complexes including various upstream modulators and downstream effectors, which may be kept together by additional adapter and scaffold proteins [7].

In 1992, this novel R-type Ca2+ channel was initially detected from a rabbit brain, which was named the BII calcium channel [25]. Its primary sequence was deduced by molecular homology cloning and sequencing of cDNA. Its transcripts were found to be distributed predominantly in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and corpus striatum. In the carboxyterminal region, 2 splice variants were found, from which BII-2 had a 272-aas-long insertion in the carboxyterminus (Fig. 2).

In 1993, a structural homolog of the new calcium channel was cloned from marine ray [12, 15, 43] and rat brain [37], which at that time was functionally expressed for the first time. Although the sequence of the rat rbE-II was structurally related to high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels, it was assumed to be a low-voltage-gated Ca2+ channel, because the rbE-II channel transiently activated at more negative membrane potentials, required a strong hyperpolarization to deinactivate and was highly sensitive to Ni2+ block. In situ hybridization showed that rbE-II messenger RNA was expressed in regions throughout the central nervous system [37]. Its predicted shorter N-terminal sequence was not confirmed by RT-PCR studies [34].

During the same time, a rapidly inactivating neuronal Ca2+ channel was identified, called doe-1 in ray (Discopyge ommata). Its expression showed that it was a high-voltage-activated Ca2+ channel that inactivated more rapidly than other known channel types like L- or P-type channels. It was insensitive towards dihydropyridine antagonists or the peptide toxin omega-Aga-IVa, respectively. This channel with novel functional properties was also sensitive towards micromolar Ni2+ concentrations as well as sensitive towards omega-conotoxin GVIA in a reversible manner [12]. At that time, a similar Ca2+ channel current was identified in rat cerebellar granule neurons [43], which was distinguished from T-type Ca2+ channels in dissociated neurons from native tissues [31].

In 1994, two human Cav2.3 sequences were published [33, 41] and both constructs were functionally expressed. In the same year, also the rabbit BII-2 variant and the mouse construct (Table 1) were identified. Additional and novel splice variants were amplified by RT-PCR [38] and full-length cloning [18, 21, 22], which showed that structural and functional details are important in different tissues. The functional implications have only partially been characterized [17, 19].

Changes of Cav2.3 transcript and expression levels in mouse models related to Parkinson disease

The neuronal Ca2+ sensor protein (NCS) was identified to be important for the viability and pathophysiology of dopaminergic (DA) midbrain neurons [11]. In a mouse model lacking NCS type 1 (NCS-1), several mitochondrial encoded proteins were reduced on the transcriptional level. Also, lower levels of Cav2.3 were detected in substantia nigra (SN) neurons from NCS-1 KO mice [36], leading to a deeper analysis of the role of Cav2.3 during the selective degeneration of DA midbrain neurons.

In an in vivo mouse model of Parkinson disease (injection of MPTP/probenecid), Cav2.3 was identified as a mediator of SN dopaminergic neuron loss [5]. In adult SN dopaminergic neurons, it was shown that Cav2.3 represents the most abundantly expressed voltage-gated Ca2+ channel subtype. It was linked with metabolic stress in these neurons or with their degeneration in Parkinson’s disease, which may occur by affecting Cav-mediated Ca2+ oscillations and/or by changing Ca2+-dependent after hyperpolarizations (AHPs) in SN dopaminergic neurons [5].

Tonic inhibition of Cav2.3 by bioavailable divalent cations (Zn2+, Cu2+)

Cav2.3/R-type Ca2+ channels are highly sensitive towards bioavailable divalent cations [23]. In the organotypic model of the isolated and superfused bovine retina, Cav2.3/R-type Ca2+ channels have early been identified to be modulated by Zn2+ [35] and Cu2+ [24], Lüke et al., in press) changing the transretinal signalling. Zn2+ and Cu2+ effects can be analysed more specifically in heterologous expression systems, which have shown that e.g. Zn2+ can either increase or inhibit Ca2+ currents mediated by recombinant Cav2.3 channels (Neumaier et al., unpublished results).

In vivo, Cav2.3/R-type Ca2+ channels are thought to be under tight allosteric control by endogenous loosely bound trace metal cations (Zn2+ and Cu2+) that suppress channel gating via a high-affinity trace–metal-binding site. Unexpectedly, in wild-type mice the intracerebroventricular administration of histidine (1 mM) rather than Zn2+ itself in micromolar concentrations is beneficial during experimentally induced epilepsy [2]. In Cav2.3-deficient mice, no beneficial effect of histidine is found and the experimentally induced seizures are less severe when Zn2+ in the presence of histidine is injected intracerebroventricularly [3].

As highly selective Cav2.3/R-type antagonists are still missing, the indirect modulation of Cav2.3 by manipulation of bioavailable cation levels may provide an additional pathway for beneficial modulation of Cav2.3/R-type Ca2+ channels.

References

Aidley DJ, Stanfield PR (1996) Ion channels. Molecules in action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Alpdogan S, Neumaier F, Dibue-Adjei M, Hescheler J, Schneider T (2019) Intracerebroventricular administration of histidine reduces kainic acid-induced convulsive seizures in mice. Exp Brain Res 237:2481–2493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-019-05605-z

Alpdogan S, Neumaier F, Hescheler J, Albanna W, Schneider T (2020) Experimentally induced convulsive seizures are modulated in part by zinc ions through the pharmacoresistant Cav2.3 calcium channel. Cell Physiol Biochem 54:180–194. https://doi.org/10.33594/000000213

Baker JJ, Burton JE, Akbar AX, Zelaya BM, Hoganson GE (2016) Case report: mutation in CACNA1E causing encephalopathy and seizure disorder; a new disorder? ACMG Ann Clin Gen Meeting March 8th - 12th: http://epostersonline.com/acmg2016/node/2302

Benkert J, Hess S, Roy S, Beccano-Kelly D, Wiederspohn N, Duda J, Simons C, Patil K, Gaifullina A, Mannal N, Dragicevic E, Spaich D, Muller S, Nemeth J, Hollmann H, Deuter N, Mousba Y, Kubisch C, Poetschke C, Striessnig J, Pongs O, Schneider T, Wade-Martins R, Patel S, Parlato R, Frank T, Kloppenburg P, Liss B (2019) Cav2.3 channels contribute to dopaminergic neuron loss in a model of Parkinson's disease. Nat Commun 10:5094. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12834-x

Breitenkamp AF, Matthes J, Herzig S (2015) Voltage-gated calcium channels and autism spectrum disorders. Curr Mol Pharmacol 8:123–132

Campiglio M, Flucher BE (2015) The role of auxiliary subunits for the functional diversity of voltage-gated calcium channels. J Cell Physiol 230:2019–2031. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.24998

Catterall WA, Wisedchaisri G, Zheng N (2017) The chemical basis for electrical signaling. Nat Chem Biol 13:455–463. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.2353

Dolphin AC (2016) Voltage-gated calcium channels and their auxiliary subunits: physiology and pathophysiology and pharmacology. J Physiol 594:5369–5390. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP272262

Doyle DA, Cabral JM, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo AL, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R (1998) The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science 280:69–77

Dragicevic E, Poetschke C, Duda J, Schlaudraff F, Lammel S, Schiemann J, Fauler M, Hetzel A, Watanabe M, Lujan R, Malenka RC, Striessnig J, Liss B (2014) Cav1.3 channels control D2-autoreceptor responses via NCS-1 in substantia nigra dopamine neurons. Brain 137:2287–2302. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awu131

Ellinor PT, Zhang JF, Randall AD, Zhou M, Schwarz TL, Tsien RW, Horne WA (1993) Functional expression of a rapidly inactivating neuronal calcium channel. Nature 363:455–458

Helbig KL, Lauerer RJ, Bahr JC, Souza IA, Myers CT, Uysal B, Schwarz N, Gandini MA, Huang S, Keren B, Mignot C, Afenjar A, Billette S, Heron DV, Nava C, Valence S, Buratti J, Fagerberg CR, Soerensen KP, Kibaek M, Kamsteeg EJ, Koolen DA, Gunning B, Schelhaas HJ, Kruer MC, Fox J, Bakhtiari S, Jarrar R, Padilla-Lopez S, Lindstrom K, Jin SC, Zeng X, Bilguvar K, Papavasileiou A, Xin Q, Zhu C, Boysen K, Vairo F, Lanpher BC, Klee EW, Tillema JM, Payne ET, Cousin MA, Kruisselbrink TM, Wick MJ, Baker J, Haan E, Smith N, Corbett MA, MacLennan AH, Gecz J, Biskup S, Goldmann E, Rodan LH, Kichula E, Segal E, Jackson KE, Asamoah A, Dimmock D, McCarrier J, Botto LD, Filloux F, Tvrdik T, Cascino GD, Klingerman S, Neumann C, Wang R, Jacobsen JC, Nolan MA, Snell RG, Lehnert K, Sadleir LG, Anderlid BM, Kvarnung M, Guerrini R, Friez MJ, Lyons MJ, Leonhard J, Kringlen G, Casas K, El Achkar CM, Smith LA, Rotenberg A, Poduri A, Sanchis-Juan A, Carss KJ, Rankin J, Zeman A, Raymond FL, Blyth M, Kerr B, Ruiz K, Urquhart J, Hughes I, Banka S, UBS H, Scheffer IE, Helbig I, Zamponi GW, Lerche H, Mefford HC (2018) De novo pathogenic variants in CACNA1E cause developmental and epileptic encephalopathy with contractures, macrocephaly, and dyskinesias. Am J Hum Genet 103:666–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.09.006

Hering S, Zangerl-Plessl EM, Beyl S, Hohaus A, Andranovits S, Timin EN (2018) Calcium channel gating. Pflugers Arch 470:1291–1309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-018-2163-7

Horne WA, Ellinor PT, Inman I, Zhou M, Tsien RW, Schwarz TL (1993) Molecular diversity of Ca2+ channel α1 subunits from the marine ray Discopyge ommata. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:3787–3791

Kaeser PS, Deng L, Wang Y, Dulubova I, Liu X, Rizo J, Sudhof TC (2011) RIM proteins tether Ca2+ channels to presynaptic active zones via a direct PDZ-domain interaction. Cell 144:282–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.029

Klöckner U, Pereverzev A, Leroy J, Krieger A, Vajna R, Hescheler J, Pfitzer G, Malecot CO, Schneider T (2004) The cytosolic II-III loop of Cav2.3 provides an essential determinant for the phorbol ester-mediated stimulation of E-type Ca2+ channel activity. Eur J Neurosci 19:2659–2668

Larsen JK, Mitchell JW, Best PM (2002) Quantitative analysis of the expression and distribution of calcium channel alpha 1 subunit mRNA in the atria and ventricles of the rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 34:519–532

Leroy J, Pereverzev A, Vajna R, Qin N, Pfitzer G, Hescheler J, Malécot CO, Schneider T, Klöckner U (2003) Ca2+-sensitive regulation of E-type Ca2+ channel activity depends on an arginine rich region in the cytosolic II-III loop. Eur J Neurosci 18:841–855

Long SB, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R (2005) Voltage sensor of Kv1.2: structural basis of electromechanical coupling. Science 309:903–908

Mitchell JW, Larsen JK, Best PM (1999) Sequence of E-type calcium channel gene isoforms from atrial myocytes and the cellular distribution of their protein products. Biophys J 76:A91

Mitchell JW, Larsen JK, Best PM (2002) Identification of the calcium channel alpha 1E (Ca(v)2.3) isoform expressed in atrial myocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1577:17–26

Neumaier F, Dibué-Adjei M, Hescheler J, Schneider T (2015) Voltage-gated calcium channels: determinants of channel function and modulation by inorganic cations. Progress in Neurobiology 129:1–36

Neumaier F, Akhtar-Schafer I, Luke JN, Dibue-Adjei M, Hescheler J, Schneider T (2018) Reciprocal modulation of Cav 2.3 voltage-gated calcium channels by copper(II) ions and kainic acid. J Neurochem 147:310–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.14546

Niidome T, Kim M-S, Friedrich T, Mori Y (1992) Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel calcium channel from rabbit brain. FEBS Lett 308:7–13

Olcese R, Qin N, Schneider T, Neely A, Wei X, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L (1994) The amino terminus of a calcium channel β subunit sets rates of channel inactivation independently of the subunit's effect on activation. Neuron 13:1433–1438

Pereverzev A, Leroy J, Krieger A, Malecot CO, Hescheler J, Pfitzer G, Klockner U, Schneider T (2002) Alternate splicing in the cytosolic II-III loop and the carboxy terminus of human E-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels: electrophysiological characterization of isoforms. Mol Cell Neurosci 21:352–365

Perez-Reyes E (1998) Molecular characterization of a novel family of low voltage-activated, T-type, calcium channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr 40:313–318

Perez-Reyes E, Schneider T (1994) Calcium channels: structure, function, and classification. Drug Dev Res 33:295–318

Perez-Reyes E, Cribbs LL, Daud A, Lacerda AE, Barclay J, Williamson MP, Fox M, Rees M, Lee J-H (1998) Molecular characterization of a neuronal low voltage-activated T-type calcium channel. Nature 391:896–900

Randall AD, Tsien RW (1997) Contrasting biophysical and pharmacological properties of T-type and R-type calcium channels. Neuropharmacology 36:879–893

Raybaud A, Baspinar EE, Dionne F, Dodier Y, Sauve R, Parent L (2007) The role of distal S6 hydrophobic residues in the voltage-dependent gating of CaV2.3 channels. J Biol Chem 282:27944–27952

Schneider T, Wei X, Olcese R, Costantin JL, Neely A, Palade P, Perez-Reyes E, Qin N, Zhou J, Crawford GD, Smith RG, Appel SH, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L (1994) Molecular analysis and functional expression of the human type E α1 subunit. Receptors & Channels 2:255–270

Schramm M, Vajna R, Pereverzev A, Tottene A, Klöckner U, Pietrobon D, Hescheler J, Schneider T (1999) Isoforms of α1E voltage-gated calcium channels in rat cerebellar granule cells - detection of major calcium channel α1-transcripts by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. Neuroscience 92:565–575

Siapich SA, Wrubel H, Albanna W, Alnawaiseh M, Hescheler J, Weiergräber M, Lüke M, Schneider T (2010) Effect of ZnCl2 and chelation of zinc ions by N,N-diethyldithiocarbamate (DEDTC) on the ERG b-wave amplitude from the isolated and superfused vertebrate retina. Curr Eye Res 35:322–334

Simons C, Benkert J, Deuter N, Poetschke C, Pongs O, Schneider T, Duda J, Liss B (2019) NCS-1 deficiency affects mRNA levels of genes involved in regulation of ATP synthesis and mitochondrial stress in highly vulnerable substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. Front Mol Neurosci 12:252. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2019.00252

Soong TW, Stea A, Hodson CD, Dubel SJ, Vincent SR, Snutch TP (1993) Structure and functional expression of a member of the low voltage-activated calcium channel family. Science 260:1133–1136

Vajna R, Schramm M, Pereverzev A, Arnhold S, Grabsch H, Klöckner U, Perez-Reyes E, Hescheler J, Schneider T (1998) New isoform of the neuronal Ca2+ channel α1E subunit in islets of Langerhans, and kidney. Distribution of voltage-gated Ca2+ channel α1 subunits in cell lines and tissues. Eur J Biochem 257:274–285

Wakamori M, Niidome T, Rufutama D, Furuichi T, Mikoshiba K, Fujita Y, Tanaka I, Katayama K, Yatani A, Schwartz A, Mori Y (1994) Distinctive functional properties of the neuronal BII (class E) calcium channel. Receptors & Channels 2:303–314

Wall-Lacelle S, Hossain MI, Sauve R, Blunck R, Parent L (2011) Double mutant cycle analysis identified a critical leucine residue in the IIS4S5 linker for the activation of the Ca(V)2.3 calcium channel. J Biol Chem 286:27197–27205

Williams ME, Marubio LM, Deal CR, Hans M, Brust PF, Philipson LH, Miller RJ, Johnson EC, Harpold MM, Ellis SB (1994) Structure and functional characterization of neuronal α1E calcium channel subtypes. J Biol Chem 269:22347–22357

Zamponi GW, Striessnig J, Koschak A, Dolphin AC (2015) The physiology, pathology, and pharmacology of voltage-gated calcium channels and their future therapeutic potential. Pharmacol Rev 67:821–870. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.114.009654

Zhang J-F, Randall AD, Ellinor PT, Horne WA, Sather WA, Tanabe T, Schwarz TL, Tsien RW (1993) Distinctive pharmacology and kinetics of cloned neuronal Ca2+ channels and their possible counterparts in mammalian CNS neurons. Neuropharmacology 32:1075–1088

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. We thank Renate Clemens for her excellent technical assistance.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG, SCHN 387/21-1 and /21-2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the special issue on Channelopathies: from mutation to diseases in Pflügers Archiv—European Journal of Physiology

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schneider, T., Neumaier, F., Hescheler, J. et al. Cav2.3 R-type calcium channels: from its discovery to pathogenic de novo CACNA1E variants: a historical perspective. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol 472, 811–816 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-020-02395-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-020-02395-0