Abstract

Perturbation of a protein away from its native state by mechanical stress is a physiological process immanent to many cells. The mechanical stability and conformational diversity of proteins under force therefore are important parameters in nature. Molecular-level investigations of “mechanical proteins” have enjoyed major breakthroughs over the last decade, a development to which atomic force microscopy (AFM) force spectroscopy has been instrumental. The giant muscle protein titin continues to be a paradigm model in this field. In this paper, we review how single-molecule mechanical measurements of titin using AFM have served to elucidate key aspects of protein unfolding–refolding and mechanisms by which biomolecular elasticity is attained. We outline recent work combining protein engineering and AFM force spectroscopy to establish the mechanical behavior of titin domains using molecular “fingerprinting.” Furthermore, we summarize AFM force–extension data demonstrating different mechanical stabilities of distinct molecular-spring elements in titin, compare AFM force–extension to novel force-ramp/force-clamp studies, and elaborate on exciting new results showing that AFM force clamp captures the unfolding and refolding trajectory of single mechanical proteins. Along the way, we discuss the physiological implications of the findings, not least with respect to muscle mechanics. These studies help us understand how proteins respond to forces in cells and how mechanosensing and mechanosignaling events may proceed in vivo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

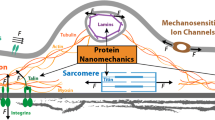

Mechanical forces are centrally involved in basic physiological processes, during both development and maintenance of normal function of differentiated cells and tissues. For example, estimates suggest that a newly synthesized polypeptide chain is exposed to an equilibrium force of ~10 pN as it exits the ribosomal tunnel [55]. Physical stresses also play a role in various pathological states. A well-known example is the heart, which responds to mechanical (pressure or volume) overload with alterations in myocardial gene expression causing dysregulation of mechanical function and, eventually, cardiac failure. For an increasing number of researchers, it has become a major goal to understand the molecular and cellular basis of mechanotransduction in tissues. Along the same line, the growing field of mechanosignaling deals with elucidating the molecular mechanisms by which cells/tissues sense physical loads and transduce them into biochemical signals to alter gene expression and modify cellular structure and function.

The complex mechanotransduction network typically contains “mechanical proteins,” a term applicable to polypeptides designed to respond to force application under physiological conditions [123]. To study the mechanical behavior of a mechanical protein, techniques are required that detect forces in the piconewton range and distances on the order of nanometers. Because of its versatility and relative ease of handling, the atomic force microscope has become the device of choice for many. A common method of mechanical manipulation by atomic force microscopy (AFM) is to pull a single molecule by a tip attached to a cantilever and probe the effect of stretch forces on protein stability. Mechanical forces are a natural protein denaturant, so the method reveals information that is likely to be of physiological relevance.

Apart from the study of how elastic proteins behave under stretch forces (covered in this review), AFM force spectroscopy has also been applied to measure adhesion forces [108], including those of individual proteins anchored in a membrane, like bacteriorhodopsin [47, 53, 100], analyze the binding forces between biotin and streptavidin [26] and the rupture forces of an antibody–antigen complex (termed “single-molecule recognition imaging microscopy”) [20, 43, 107, 125], or infer the strength of a covalent bond [36]. Similarly, the so-called force–volume mode of the AFM can detect the presence of specific marker proteins on the surface of a cell by their binding strength to an antibody-coated AFM cantilever tip [124], a technique that distinguishes, for instance, red blood cells of group A from those of group B [37]. Single molecules other than proteins have been deformed by pulling on them using the AFM; prominent examples include polysaccharides [84, 86, 111] and double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) [13, 18, 65, 113].

Arguably, the best-known molecule studied by AFM force spectroscopy is titin, a giant elastic protein in the sarcomeres of cardiac and skeletal muscles (Fig. 1a). Since the landmark publication on titin some 10 years ago [110], many other mechanical proteins have been probed by mechanical force in a similar manner, such as tenascin/fibronectin [14, 95, 96], alpha-spectrin [114], ubiquitin [9, 118], ankyrin [64], or fibrinogen [7], to name but a few of the more than 50 different proteins analyzed to date [126]. These studies have shown a characteristic, often multipeaked, force–displacement pattern for each mechanical protein, demonstrating the resistance to unraveling. What we have learned from these contributions is that many mechanical proteins have evolved to withstand repeated cycles of stretching and force release. In this review, we will focus on titin as a prime example of a mechanical protein studied by single-molecule AFM, compare the “classical” AFM force–extension mode to the novel force-ramp and force-clamp modes, and discuss physiological implications of recent results obtained using these methods.

Titin isoforms in muscle sarcomeres and engineered titin constructs used for AFM force spectroscopy. a Sarcomere model highlighting the titin springs. b Domain structures of I-band titin regions in the main titin isoform classes, N2B and N2BA in cardiac muscle, and N2A in skeletal muscles. Blue bars and text indicate the position of those domains in titin, for which recombinant constructs have been engineered. c Schematics of four different types of engineered titin constructs. d Scheme of AFM setup for force spectroscopy

The “stretchy” titin segment: an adjustable molecular spring in muscle sarcomeres

Titin (also known as connectin [30]) is the largest known protein in nature. In humans, there is a single titin gene (on chromosome 2q31) coding for a total of 38,138 amino acid residues or a polypeptide with a maximum molecular mass of 4,200 kDa [1]. Approximately 90% of titin’s mass is made up of globular domains of the immunoglobulin (Ig) or fibronectin-type-III (FN3)-like folds; the remainder is unique sequence insertions [59]. An entire titin filament spans from the Z-disk to the center of the sarcomere, but the “stretchy bit” of titin is in the so-called I-band segment and varies greatly in length in different muscle types (Fig. 1b). Three main titin isoform classes with different I-band compositions are distinguished: N2B (~3.0 MDa) and N2BA (3.2–3.7 MDa) in the heart and N2A (~3.3–3.7 MDa) in skeletal muscles (Fig. 1b).

All isoforms express a “proximal” (I1–I15) and a “distal” (I84–I105) region composed of tandemly arranged Ig domains, as well as a “PEVK”-domain, named so for its high content in proline (P), glutamic acid (E), valine (V), and lysine (K) residues. Whereas an Ig domain comprises ~90–100 amino acids built in β-sandwich architecture [105], the PEVK domain contains coiled conformations that are elongated when the muscle is stretched [39, 40, 66, 72, 76, 92, 127]. Characteristic for the cardiac titin isoforms is a so-called N2-B region encompassing a long unique sequence (N2Bus) flanked by Ig domains. Cardiac N2BA and skeletal N2A isoforms additionally contain an “N2-A” domain and a central (“middle” or “variable-length”) Ig-domain region (I28–I79). Extensive alternative splicing occurring in this Ig domain region and in the PEVK domain (Fig. 1b) adjusts the contour length of the I-band titin [29] and is responsible for the great elastic diversity of the titin springs [94, 106]. The multiple functions of the titin proteins in muscle have been more extensively reviewed elsewhere [38, 78].

AFM stretching of engineered titin proteins: detecting single molecules by “fingerprinting”

Single-molecule AFM stretch experiments have been performed with isolated native titin [51, 110] or titin-like protein from invertebrate muscles [11]. However, a great many studies have taken advantage of molecular engineering techniques to create recombinant constructs of various titin regions for examination by AFM [10, 15, 27, 35, 58, 63, 66–68, 85, 92, 97, 110, 112, 134–136]. Figure 1b (bottom of panel) lists all the parts of I-band titin that have, to our knowledge, so far been analyzed by AFM force spectroscopy using engineered fragments. Some of the constructs are multidomain proteins in which the modules are serially linked according to their natural sequence in the native molecule, e.g., (I24–I25-N2Bus-I26–I27) or (I91–I98) (Fig. 1c, upper two panels). Various other constructs are so-called polyproteins [16, 21] consisting of repeats of identical domains, e.g., (I4)8 or (I91-PEVKc)3 (Fig. 1c, lower two panels), which show unique mechanical features when stretched in AFM experiments [25].

In the actual AFM force–extension experiment, a drop of a protein suspension in physiological salt buffer is deposited onto a flat surface (a cleaned cover glass or mica, or a gold-coated glass surface), which can be moved with Angstrom accuracy by a piezoelectric actuator. When the tip of a flexible silicone nitride cantilever is brought in contact with the surface, sporadic binding can occur between the protein molecule and the tip atoms. If the other end of the molecule is immobilized to the surface, the protein can be stretched by increasing the distance between cantilever and surface (Fig. 1d). Forces in the range of a few tens of piconewtons up to several nanonewtons are measurable by detecting the deflection of the cantilever onto which the beam of a laser diode is focused. The reflected beam illuminates a two-segment photodiode, which records a differential signal that is fed into a feedback circuit (Fig. 1d). Because the spring constant of the cantilever can be precisely calculated using the equipartition theorem [44], the cantilever deflection is commensurable to the force applied to the protein.

The likelihood that a single protein attaches to the cantilever tip is very low. With usually many molecules being tethered, the number of which cannot be controlled, a critical step in the analysis is to find a way of detecting those rare events when truly a single protein is stretched. Therefore, an ingenious approach has been developed to “find the needle in the haystack” by using the mechanical fingerprint of an engineered polyprotein [6, 15, 16, 21, 25, 67]. Stretching a polyprotein of the kind shown in Fig. 2a—(I91)8 according to the nomenclature by Bang et al. [1] but also known as (I27)8 according to the old nomenclature by Labeit and Kolmerer [59]—results in a characteristic sawtooth pattern, where each peak corresponds to the unfolding of an Ig domain (Fig. 2a–e). Because all Ig domains are structurally identical in this homopolyprotein, the unfolding forces are similar (although not identical), and the peaks are equally spaced—which is the fingerprint. In contrast, multiple or nonspecific tethers result in irregular peak spacing and no fingerprint (example in Fig. 2d, inset). Thus, the use of concatemers (proteins encoded by long continuous DNA molecules containing multiple copies of the same sequences linked in series) unambiguously distinguishes between multiple or nonspecific surface–cantilever interactions and trajectories resulting from stretching a single polyprotein.

Single-molecule AFM force–extension measurements on a titin homopolyprotein. a–d Series of images demonstrating the sawtooth pattern obtained by stretching a single modular titin polyprotein of the type (I91)8 in the force–extension mode at a constant velocity. Each peak indicates unfolding of an Ig domain. Note the regular peak spacing which suggests a single protein was pulled (“fingerprint”). d (inset) Irregular peak spacing observed with multimolecule tethers or nonspecific interactions. e Peak spacing (contour-length increment, ΔL) measured by applying wormlike chain (WLC) model fits (see Eq. 1) to individual peaks. f Pulling-speed dependence for unfolding forces observed for titin Ig domains I91 and I1. Open circles connected by lines correspond to Monte Carlo simulations (graph reproduced, with permission, from Li and Fernandez [68])

The mechanical fingerprint of the titin constructs can be parameterized using models of the polymer elasticity theory. For instance, the increase in the end-to-end length (x) of the polyprotein when one Ig domain unfolds can be estimated with the wormlike chain (WLC) model of entropic elasticity [12, 83]. This model predicts that the stretch force (F) is related to the fractional extension (x/L) of the chain by

where A is the persistence length, a measure of the chain’s bending rigidity, k B is the Boltzmann constant, T is absolute temperature, x is extension, and L is the contour length. Fitting this model to successive sawtooth peaks in the measured force trace reveals that each unfolding event increases the contour length of the homopolyprotein by a constant value, ΔL, thus providing a precise fingerprint (Fig. 2e). In the case of (I91)8, ΔL is 28.1 nm; the value measured for other Ig domains depends on the number of constituent amino acids but is typically 27–31 nm [67, 68]. Considering the size of a folded Ig domain of about 4.5 nm [45], these titin modules increase their contour length upon unfolding by a factor of ~7, which explains why the force drops dramatically after each unfolding event. In conclusion, by combining protein engineering and AFM force spectroscopy, it is possible to establish, with high confidence, the mechanical behavior of a single molecule. The fingerprinting technique has been successfully applied to study many different titin domains.

Mechanical unfolding and refolding of titin Ig domains by force–extension

In the AFM force–extension mode, a molecule is stretched at a constant velocity, while the force varies dynamically throughout the experiment. This mode, used in most AFM force spectroscopy studies so far, detects the unfolding forces of the individual domains in a modular protein. As for titin pulled at a physiological stretch speed of ~1 μm/s, the maximum force at which Ig domain unfolding occurs, F max (the unfolding force), ranges from ~130 pN in the proximal Ig domain I1 [68] to 300 pN in the distal Ig domain I96 (Fig. 3a) [67], while many other titin Ig domains, including I91, show a value near 200 pN (Fig. 2f). This compares to a range of 50–200 pN for FN3-like domains [14, 99, 112], 35 pN for alpha-spectrin [114], ~40 pN for a single ankyrin repeat [64], and up to 200 pN for ubiquitin [17]. A survey of the F max values for more than 7,500 mechanical proteins predicted using a coarse-grained molecular dynamics model revealed that the domain-unfolding forces vary between 0 and ~350 pN, in good agreement with the available experimental data [126].

Different mechanical stabilities of the molecular spring elements in titin revealed by force–extension experiments on engineered polyproteins. a Force–length trajectory for a homopolyprotein containing identical Ig domains, (I96)8. Parameters A unfold. (persistence length after unfolding of at least one module) and ΔL were calculated from WLC model fits (red curves) according to Eq. 1. b Trajectory for a heteropolyprotein containing the titin N2B-unique sequence (N2Bus) flanked by three I91 Ig domains on either side. This tether contained the whole N2Bus of 572 amino acid residues and four Ig domains providing a clear fingerprint for a single molecule (regular spacing of unfolding peaks). WLC fit to first unfolding peak (blue curve) parameterizes the mechanical properties of the N2Bus. c Trajectory for a heteropolyprotein consisting of three in-series-linked identical motifs containing I91 and the 186-residue PEVK domain of the cardiac N2B-titin isoform (PEVKc). This tether contained two Ig domains and at least one full PEVK domain. WLC fit to first unfolding peak (yellow curve) parameterizes the mechanical properties of PEVKc. d Titin as a three-element entropic spring in cardiac (half-)sarcomeres. The model illustrates the sequence of unraveling events during the coextension of short N2B and long N2BA isoforms in a cardiac half-sarcomere, in the physiological sarcomere-length (SL) range from slack to 2.4 μm. For clarity, schemes do not show the real number of Ig domains in the I-band titin region (compare with Fig. 1b)

The unfolding forces increase with the pulling speed (Fig. 2f). This observation is expected, because force-induced unfolding is a process in which the increasing external force lowers the activation barrier between the folded and unfolded state so that within the time span of the experiment, thermal fluctuations succeed in overcoming the unfolding barrier [3, 23, 110]. From the speed dependence of unfolding forces, one can estimate the unfolding rate constant, α, using the Bell model [3, 23] according to

where α 0 is the unfolding rate in the absence of external force, F is the applied force, and Δx is the distance to the unfolding transition state (0.25–0.35 nm for titin Ig domains [68]). Estimates for α 0 range from 5 × 10−3 to 3 × 10−5 s-1 for different Ig domains [15, 68, 110, 136], suggesting that the mechanically weakest domains, like I1, unfold on average every few minutes even when the stretch force is 0. The probability of unfolding, P u, of the protein pulled at constant velocity can be calculated as P u = αΔt using Monte Carlo simulations (where Δt is the polling interval), which use a simple algorithm computing at any given extension and force whether a domain has unfolded but also predict how the unfolding force shifts with the pulling velocity [15, 68, 110]. Within a pulling-speed range covering three orders of magnitude, the force at which 100% of titin Ig domains are predicted to be unfolded (=F max) varies by approximately a factor of 2 (Fig. 2f).

These data showed that Ig domain unfolding does not simply occur above a certain “threshold” force. Instead, it must be viewed as a stochastic process in which the unfolding probability is low (but above 0) in the absence of external force and increases with the applied force level to reach 100% at a force (F max) whose magnitude depends on the pulling speed. Results also suggested that most or all distal Ig domains in titin have high resistance to forced unfolding, whereas the proximal Ig domains are mechanically weaker [67], and their unfolding in response to elevated stretch forces is therefore more likely [75, 89]. However, the relatively high mechanical stability of these Ig modules rules out Ig domain unfolding as the principal mechanism by which titin springs respond to stretch forces in vivo.

What causes the resistance to unfolding in titin Ig-domains? An invaluable contribution to understanding the critical events leading to mechanical unfolding has come from steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulations and other modeling approaches [4, 28, 31, 32, 54, 80, 81, 85, 103, 104, 137], which have used the available atomic structures of the titin Ig domains I1 [88] and I91 [45]. For I91, SMD simulations showed that mechanical force application first breaks two backbone hydrogen bonds between the beta-strands A and B—an event that is sometimes projected in AFM recordings as a small “hump” during the force rise (see Figs. 2b and 3a) [41, 48, 67, 85]. This unfolding intermediate state is followed by the breakage of additional hydrogen bonds between the beta-strands A′ and G to cause complete unfolding. In comparison to I91, the Ig domain I1 shows a simpler two-state transition during unfolding [32, 67, 68]: The backbone hydrogen bonds between beta-strands A–B and A′–G rupture simultaneously, and the unfolding of I1 occurs in an all-or-none fashion. A twist in the story is that the I1 domain can form a disulfide bridge between beta-strands C and E, which could stabilize this domain under oxidative stress conditions in muscle cells [68, 88]. In sum, comparisons of AFM data with SMD simulation studies have provided us with atomic-level insights into the events taking place during force-induced unfolding of a titin Ig domain. Titin has served as an important model for understanding key issues of protein unfolding.

The Ig domains unfold reversibly. Refolding occurs spontaneously in physiological salt buffer upon lowering the stretch force level; misfolding is a rare event [97] despite the absence of chaperones. Reversible unfolding of titin has been studied by AFM force–extension using a double-pulse protocol, where the protein is first completely unfolded but not allowed to detach from the cantilever, so that it can be relaxed again and—after a variable waiting period—stretched a second time [11, 15, 97, 110]. The rate of refolding is calculated based on the percentage of domains that have folded during the waiting time, which can be determined by counting the unfolding peaks in the second stretch pulse. For titin I91, refolding rates of ~1 s−1 at room temperature were found [15], whereas faster rates up to 15 s−1 at 25°C were recently reported for titin-like Ig/FN3 domains from invertebrate muscle [11]. The observation that titin Ig domains can be unfolded in a reversible manner raises the possibility that this mechanism is of importance in vivo. This issue will be discussed in more detail below in the context of refolding studies using AFM force clamp. Reversible unfolding of Ig domains may in part explain the hysteresis appearing in stretch–release cycles of nonactivated sarcomeres [50, 70, 89, 129].

Force–extension studies demonstrate different mechanical stabilities of the molecular spring elements in titin

AFM force–extension experiments on engineered polyproteins have been extremely useful for understanding the molecular mechanisms of titin elasticity in vivo. To this end, the generation of heteropolyproteins (Fig. 1c) has been instrumental [66, 67]. Concatemers of the type (I91)3-N2Bus-(I91)3 [67, 75] or (I91-PEVKc)3 [66, 67, 76] essentially represent synthetic “mini-titins” exhibiting mechanical features (Fig. 3b,c), which one also expects in the full-length titin. In these heteropolyproteins, the I91 Ig domains again serve as the mechanical fingerprint to detect a single-molecule tether. A typical force–extension curve of (I91)3-N2Bus-(I91)3 shows a long low-force region before the first unfolding peak, corresponding to the extension of the N2B-unique sequence (Fig. 3b). In this example, the tether contained four I91 Ig modules (four unfolding peaks spaced at 28 nm) plus the whole intervening N2Bus, which according to WLC fits (blue curve in Fig. 3b) had a persistence length, A, of 0.7 nm and a contour length, L, of ~200 nm. The latter value matches the contour length expected for a fully extended N2Bus of 572 residues [67, 75]. A representative force trace for (I91-PEVKc)3 also shows an initial low-force region during which PEVK extension occurs, followed by two Ig-unfolding peaks spaced at 28 nm (Fig. 3c). Thus, the tether contained two I91 Ig modules and at least one full PEVK segment of 186 residues (this PEVK domain is from the cardiac N2B isoform). In this example, the persistence length for the PEVK region was 1.0 nm, and the contour length was ~80 nm. One conclusion drawn from these experiments is that the unique sequences in titin generate elastic forces mainly according to an entropic-spring mechanism, although evidence abounds suggesting that additional factors determine the elasticity of the PEVK domain [27, 58, 72, 76, 92, 132, 137]. In any case, these and related studies [27, 58, 62, 66, 67, 92, 135] clearly demonstrated that the PEVK domain and the N2Bus extend at forces at which the Ig domain unfolding probability is still very low.

If one compares the WLC parameters for the distinct molecular-spring elements in titin, it becomes immediately obvious that these elements have different mechanical stabilities. The WLC model (Eq. 1) predicts that the force needed to extend a polymer chain critically depends on the persistence length, A: The smaller the persistence length, the higher is the force. Therefore, upon stretching titin, the PEVK domain (A ~ 1 nm) will begin to unravel before the N2Bus (A ~ 0.7 nm) does [67]. However, even before these unique sequences extend, there will be a straightening out of titin’s Ig domain regions because those regions have a much longer persistence length of greater than or equal to 10 nm [67, 73, 75, 130]. Taken together, the AFM data have allowed for a prediction of how the different titin segments extend in the sarcomere (Fig. 3d). Beginning from slack sarcomere length, low stretch forces will first straighten out titin’s proximal and distal tandem Ig regions. Once the extensibility of the (folded) Ig domain regions is largely exhausted, the unique sequences will begin to extend, first the PEVK domain and second (only in heart muscle) the N2Bus [67, 135]. This model essentially confirmed previous ideas about titin segment extension in vivo proposed on the basis of in situ measurements of titin extensibility using immunolabeling techniques [34, 71, 72, 74, 127].

Notably, owing to the coexpression of N2B and N2BA isoforms in the half-sarcomeres of cardiac muscle (Fig. 3d), the fractional extension (x/L) in situ is much higher for the short N2B than for the longer N2BA I-band segment. Within the physiological sarcomere-length range in the heart (~1.8–2.4 μm), the longer N2BA springs will only straighten out their Ig regions but not unravel the unique sequence insertions (Fig. 3d). Therefore, at a given sarcomere stretch state, the N2B isoform will be stiffer than the N2BA isoforms. Nature in fact uses alterations in the composition of stiff vs compliant titin isoforms to adjust the passive stiffness of the cardiac myocytes both during fetal/perinatal development [57, 60, 102, 133] and in chronic human heart disease [82, 91, 93]. The AFM studies have greatly helped us understand the molecular basis for these stiffness adjustments.

Novel approaches to studying unfolding–refolding by AFM: force ramp and force clamp

In force-clamp spectroscopy, a protein molecule is held at a constant (or ramped) stretching force, which allows observing the unfolding and refolding processes as a function of time. Force clamp at the single-molecule level has previously been used to characterize the function of molecular motors by optical tweezers [115, 131]. Using the force-clamp mode with the AFM [11, 24, 98] has several advantages over using the force–extension mode, because force-dependent parameters can be accurately measured with the applied force being controlled throughout the experiment. In the example shown in Fig. 4, a recombinant construct containing five Ig domains of a titin-like protein (kettin from insect muscle) was pulled by rapidly sweeping over a wide force range, from 0 to 200 pN within ~1 s [11]; this mode has been termed “force ramp” [87, 98]. For comparison, the sawtooth pattern of this construct in the force–extension mode is shown in Fig. 4 (inset), revealing an average Ig domain unfolding force of ~200 pN. In the force-ramp or force-clamp mode, the main readout is protein length (distance between cantilever and surface), and unfolding events are therefore detected in the length-vs-time trace as a staircase (Fig. 4, left panel), where each step corresponds to the unfolding of one module. In this mode, five steps indicate unfolding of all Ig domains in the construct. The force-vs-time trace shows a small indentation associated with each step, caused by the reaction of the force feedback. A strength of this AFM mode is the effective way of obtaining the unfolding probability, P u, of the Ig domains at different forces from a relatively small number of trajectories; measurements of speed dependence are not necessary [11, 98]. The data in Fig. 4 (right panel) demonstrate that P u changes from 0.2 to 1.0 over a force range of 100–200 pN. An unfolding probability of 1.0 at greater than or equal to 200 pN is consistent with the average unfolding force of these Ig domains in the force–extension mode being ~200 pN. In summary, the force-ramp technique directly measures the force dependence of the unfolding probability of a modular protein.

AFM force-ramp mode. Left panel, a recombinant construct containing five Ig domains from a titin-like protein (kettin) of Drosophila muscle was force-ramped in a sweep from 0 to 200 pN at a pulling speed of 150 pN/s. Right panel, plot of the unfolding probability, P u (calculated as shown in the graph, using Δx u = 0.17 nm and α 0 = 9 × 10−3 s−1) as a function of the applied force, obtained from force-ramp measurements on the same construct. Inset, shown, for comparison, are a sawtooth pattern and the histogram of Ig domain-unfolding forces for this construct. The figure was reassembled from Figs. 3b,c and 4c,d in Bullard et al. [11]

The force-clamp mode has been crucial in obtaining a wealth of new information on the mechanical unfolding of modular proteins and gaining real insight into the folding process of these proteins [8, 24, 98, 118]. As the name “force clamp” suggests, in this mode, a single molecule is held at a constant pulling force over time. In case the molecule is a polyprotein, e.g., (I91)8 (Fig. 5), the length-vs-time trace exhibits a staircase in which the step height, Δl, is constant at a given force and serves as the fingerprint for the unfolding of an Ig domain (Fig. 5b–e). For the same homopolyprotein, the value for Δl is always below that for the contour-length increment, ΔL, calculated by fitting the WLC model (Eq. 1) to the unfolding peaks in force–extension traces (see Fig. 2; ΔL I91 = 28.1 nm) because the unfolded domain recoils somewhat. In the example of Fig. 5, where the clamp force was 175 pN, Δl I91 is 25 nm, which is very similar to the value predictable using the WLC model (Eq. 1) with A = 0.38 nm, ΔL = 28.1 nm, and F = 175 pN. One advantage of force clamp over force–extension is apparent by comparing Figs. 2 and 5: In force clamp, unfolding is readily measured as a function of time, and altering the clamp-force level also allows determining the force dependency of unfolding in a direct manner (see below).

Single-molecule AFM force-clamp measurements on a titin homopolyprotein. a–e Series of images demonstrating the staircase pattern obtained by stepwise unfolding a single modular polyprotein of the type (I91)8 under a constant force of 175 pN. Each step indicates unfolding of an Ig domain, also marked in the force trace as a small indentation resulting from the system’s feedback. Note the regular step size, Δl i, of 25 nm (arrowheads in e), which suggests a single protein was pulled (“fingerprint”). In e, t i indicates the dwell time a module remains in the folded state, measured from the moment of force application. f Example of how the unfolding probability, P u, is calculated by fitting a single exponential to the staircase pattern. Inset, plot of the logarithm of the rate of unfolding, α, vs clamp force, for titin I91 constructs; the linear fit was redrawn from Fig. 5c in Garcia-Manyes et al. [33]. The fit, based on Eq. 2 in the text, yielded α o = 7.2 × 10−4 s−1 and Δx = 0.19 nm

In the unfolding staircase during force clamp, each step marks the unfolding dwell time, t, which is defined as the time it takes for each module in the chain to unfold, measured from the time point the force is applied (Fig. 5e). Recording the dwell times for a large number of individual unfolding events allowed for a statistical analysis of the system’s kinetics [9, 33, 98]. Measurements showed that for a polyprotein of titin I91, the dwell-time distribution follows a single exponential (although significant deviations exist hinting at a more complex energy landscape during unfolding [8, 9, 98]), suggesting that the mechanical unfolding events in the polyprotein are independent of the unfolding history [98]. These data implied that there is no mechanical coupling between unfolding Ig domains. Recent work comparing the unfolding of polyproteins and monomers of I91 under force clamp [33] has confirmed this view: The modules unfold independently of one another.

The usefulness of the force-clamp mode is further illustrated by the fact that one can straightforwardly deduce the unfolding probability, P u, of the Ig domains (without requiring Monte Carlo simulations as in the case of force–extension data) by fitting a single exponential to the length-vs-time trajectories, as done in Fig. 5f; a few averaged trajectories are sufficient to obtain P u. This analysis has been done for (I91)8 unfolding under different clamp forces from 80 to 200 pN [33]. The rate constant for unfolding, α, obtained from exponential fits like the one shown in Fig. 5f, was found to be exponentially dependent on the applied force. Plotting the logarithm of α against the clamp force and fitting a straight line to the data using Eq. 2 (the Bell model; Fig. 5f, inset) yielded an unfolding rate at zero force, α 0, of 7.2 × 10−4 s−1 [33], close to the value found in force–extension studies on I91. The results were similar for the polyprotein (I91)8 and monomers of I91 suggesting that nonspecific interdomain or domain–surface interactions potentially influencing the unfolding are likely to be absent. A general conclusion drawn from these studies is that unfolding at a given force is stochastic and may follow a simple two-state (Markovian) kinetic process, whereas the rate of unfolding increases exponentially with the force level.

Taken together, the unfolding measurements under force clamp have provided a faithful description of the mechanical stability of modular proteins and deepened our knowledge about how mechanical proteins like titin behave under external force. It is not unreasonable to expect that these experiments will eventually turn out to be extremely useful for understanding how proteins respond to mechanical forces in the cell and how mechanosensing or mechanical signaling are accomplished in vivo.

Refolding of titin Ig domains under force

An exciting new finding is that the force-clamp studies capture the folding trajectory of single modular polypeptides like ubiquitin [9, 24], titin-like protein [11], or titin (I91)8 [33]. In these experiments, the modular protein was first unfolded at a high force and then quenched at a lower force to trigger refolding (Fig. 6). For all protein types studied, the folding trajectories revealed three distinct stages (marked in Fig. 6a) during the low-force quench: (I) a fast phase corresponding to the initial elastic recoil of the unfolded polypeptide chain, (II) a slow phase characterized by large fluctuations in end-to-end length frequently associated with an overall decrease in length (Fig. 6a,b,d), and (sometimes) (III) another fast phase corresponding to the final collapse of the polypeptide chain (under force) to its folded length (Fig. 6a). Refolding of the domains during force quench was confirmed in a second pulse back to high force, which showed the characteristic steps indicating unfolding (Fig. 6a,b,d), unless the protein had been held before at a force too high to allow refolding (Fig. 6c). It can be seen that the titin domains collapse and refold in a complex folding trajectory and not stepwise like in the unfolding trajectory.

Collapse and refolding of Ig domains under force. a–c AFM force-clamp on a titin-like protein from insect muscle (projectin) studied for domain refolding at quench forces of a 15, b 30, and c 48 pN. Molecules were first unfolded and extended at a high force, then relaxed to study refolding, and finally pulled again to high force to test whether refolding had occurred. Actual force levels are indicated in the panels. Note the three phases of collapse/refolding during force quench, marked (I)–(III) in a. d Length–time trajectory for a single titin polyprotein, (I91)8, under force clamp. The Ig domains refold against a force of 25 pN. For further details, see text. a–c are taken from Fig. 6 in Bullard et al. [11]; d was reproduced, with permission, from Fig. 10C in Garcia-Manyes et al. [33]

The original conclusion that the folding may be cooperative between the modules in the polymer chain [24]—unlike the stochastic, two-stage process observed for the unfolding—triggered discussions on how to interpret the force-clamp data. It was suggested that the apparent cooperativity could be due to aggregation between the neighboring domains within the polyprotein [121] or to a masking of refolding steps by large thermal fluctuations of the unfolded polyprotein [5]. However, these interpretations did not hold up in light of the fact that monomers of ubiquitin or titin I91 show a collapse/refolding behavior, which is very similar to that of the multimodule proteins, demonstrating that the folding pathways are not affected by the presence of neighboring domains [33]. Modeling studies on I91 also suggested that the refolding pathways are genuinely heterogeneous [69], a proposition confirmed by experiment [132]. One can conclude that a mechanically unfolded protein is likely to first collapse from an extended state to a “molten globule,” a state in which it dwells for a variable lifetime, before it actually refolds. These findings and conclusions are remarkable because they imply that the energy landscape explored during refolding of a protein that has been mechanically denatured is different from that explored during refolding of a thermally or chemically denatured protein [69, 132], which until recently was the only way to study protein folding (usually done in bulk biochemistry experiments). AFM force clamp has thus offered unprecedented glimpses into physiologically relevant mechanisms driving protein folding.

Perturbing a protein away from its native state by mechanical force is a natural process, as many cells live in an environment that is under mechanical stress [46]. Therefore, the mechanical stability and conformational diversity of a protein under force are important parameters in nature [9]. These parameters are readily determinable by single-molecule force clamp. Just like the statistical analysis of single-molecule kinetics of biological reactions has revealed the mechanisms of important processes—e.g., the function of ion channels in cell membranes [19, 42], the evoked synaptic transmission in neurons [2], or the contraction of muscle cells [90]—the results obtained in AFM force-clamp measurements are likely to have a great impact on how we will view the function of mechanical proteins in vivo.

Titin Ig domain refolding: implications for understanding titin mechanics in muscle

The force-clamp experiments directly proved that Ig domains can refold within seconds against significant stretching forces (Fig. 6) of less than or equal to 30 pN (titin-like proteins from insect muscle) [11, 61] or less than or equal to 25 pN (titin I91) [33]. These findings confirmed and extended previous reports demonstrating that refolding can occur even when the protein is not fully relaxed [49, 110]. Some time ago, it was proposed that individual titin Ig domains unfold reversibly in vivo to provide the necessary extension during stretch of muscle sarcomeres [22, 122]. However, the issue of whether unfolding and refolding take place in muscle is still unresolved. Based on experimental and modeling studies on isolated myofibrils, it was concluded that massive Ig domain unfolding cannot happen in sarcomeres, whereas a few Ig domains per titin molecule could nevertheless unfold in response to rapid stretching [89]. Ig domain unfolding was suggested to contribute to the phenomenon of stress relaxation in stretched nonactivated muscle fibers, i.e., force decay at constant length. Single molecules of titin did indeed show stepwise force relaxation when mechanically manipulated by optical tweezers [129]. Recent evidence also suggested that FN3 domains in fibronectin, which readily unfold in AFM force spectroscopy measurements, unfold in native extracellular matrix fibrils, as well [120].

In contrast, when a skeletal muscle fiber was stretched and the position of a titin antibody to the N2-A segment—at the C-terminal end of a long titin section including the proximal and variable-length Ig domain regions (Figs. 1b and 7)—determined by immunoelectron microscopy, no time-dependent rearrangements were found relative to the Z-disk, suggesting a lack of Ig domain unfolding [128]. This and a related study on cardiac myofibrils [77] concluded that the Ig domains may be more stable in situ than predicted from single-molecule mechanical measurements. To support this conclusion, one can consider the confined environment [130] and abundance of viscous forces [101] in the sarcomere, which may affect the conformation and dynamics of the titin springs in situ. Further, the in vivo rates of unfolding and refolding could be different than those measured in vitro because of multiple inter- and intramolecular interactions involving titin [130]. However, in single-molecule mechanical experiments using multidomain proteins, the local effective protein concentration is always high, owing to the very nature of the polyprotein construct. This notwithstanding, the individual unfolding and folding pathways for a polyprotein are similar to those obtained for the respective monomer over a wide range of forces [33]. Furthermore, the elastic properties of relaxed muscle fibers are not affected by the presence of 4% dextran in the bathing medium [109]. As dextran shrinks the myofilament lattice spacing [56], an effect on the elasticity would have been expected if steric hindrance influenced the titin mechanics. Clearly, the question of whether molecular crowding alters titin’s mechanical properties, including the Ig domain unfolding/refolding rates, requires further experimental testing.

In this paper, we offer a simple explanation why under physiological conditions in relaxed human soleus muscle fibers Ig domain unfolding was not detectable [128]. If titin Ig domains unfold in the sarcomere but also refold rapidly under relatively high forces, a model of the kind shown in Fig. 7 can be proposed: Upon stretch, a few Ig domains per titin strand may unravel, but even during extended waiting times in the stretched state, an antibody to the N2-A epitope would remain stationary relative to the Z-disk because the initially unfolded domains will refold (arrowheads in Fig. 7, bottom panel), while other modules unfold. Eventually, there will be a dynamic equilibrium between unfolding and refolding. This testable model could be used as a working hypothesis to further examine the possibility of Ig domain unfolding in vivo. If Ig unfolding–refolding did occur in sarcomeres, it could act as a shock absorber mechanism to help prevent irreversible damage to the muscle cells during application of elevated stretch forces.

Future perspectives

What started a decade ago as a brilliant idea to mechanically manipulate titin filaments and engineered titin constructs using the AFM [110] has developed into a full-fledged field investigating important issues of force-induced protein unfolding and refolding in many different mechanical proteins or other mechanically active molecules. This field has long matured beyond the phenomenological and now addresses a variety of important biological questions, including, e.g., the relationship between protein structure and response to external force or the relevance of single-molecule data to physiological mechanisms. Titin remains a focus of attention, as well. Studies on the reversible unfolding of titin Ig domains continue to teach us important lessons about the response of mechanical proteins to stretching forces and the mechanisms by which biomolecular elasticity is accomplished.

An important issue in future work will be how conditions in AFM force spectroscopy experiments could be adapted to better mimic the physiological setting. This might include: realizing single-molecule force measurements in a protein’s natural environment [47, 53], optimizing ambient conditions (be aware, for example, of the viscosity and the reducing environment in cells [63]), engineering and investigating multimodular proteins in parallel [117] to obtain well-oriented homotypic aggregates, which are frequently found in vivo [79], or studying alterations in single-molecule mechanical properties induced by interaction with a ligand (e.g., a chaperone) [10] or phosphorylation by a protein kinase. The latter could turn out to be extremely useful for understanding mechanosensing and mechanosignaling events, which are of special importance not only in muscle cells, at the submolecular level. To this end, single-molecule AFM force spectroscopy may be combined with single-molecule fluorescence imaging techniques (e.g., total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy or fluorescence resonance energy transfer) to detect mechanical and biochemical signaling events at the same time. This technically challenging task has already revealed promising results [52, 116] but requires further refinement. A different line of research will be directed at employing AFM force spectroscopy in combination with protein engineering techniques to create protein-based advanced materials with novel mechanical properties [119]. Finally, by combining experimental and theoretical (simulation) approaches [123], the exciting and expanding field of mechanotransduction will be on a faster track to reach its ultimate goal: a better understanding of the mechanisms by which cells sense and process mechanical information.

References

Bang ML, Centner T, Fornoff F, Geach AJ, Gotthardt M, McNabb M, Witt CC, Labeit D, Gregorio CC, Granzier H, Labeit S (2001) The complete gene sequence of titin, expression of an unusual approximately 700-kDa titin isoform, and its interaction with obscurin identify a novel Z-line to I-band linking system. Circ Res 89:1065–1072

Bekkers JM, Stevens CF (1990) Presynaptic mechanism for long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 346:724–729

Bell GI (1978) Models for the specific adhesion of cells to cells. Science 200:618–627

Best RB, Fowler SB, Herrera JLT, Steward A, Paci E, Clarke J (2003) Mechanical unfolding of a titin Ig-domain: structure of transition state revealed by combining atomic force microscopy, protein engineering and molecular dynamics simulation. J Mol Biol 330:867–877

Best RB, Hummer G (2005) Comment on “Force-clamp spectroscopy monitors the folding trajectory of a single protein”. Science 308:498

Brockwell DJ, Beddard GS, Clarkson J, Zinober RC, Blake AW, Trinick J, Olmsted PD, Smith DA, Radford SE (2002) The effect of core destabilization on the mechanical resistance of I27. Biophys J 83:458–472

Brown AE, Litvinov RI, Discher DE, Weisel JW (2007) Forced unfolding of coiled-coils in fibrinogen by single-molecule AFM. Biophys J 92:L39–L41

Brujic J, Hermans RI, Walther KA, Fernandez JM (2006) Single-molecule force spectroscopy reveals signatures of glassy dynamics in the energy landscape of ubiquitin. Nat Phys 2:282–286

Brujic J, Hermans RI, Garcia-Manyes S, Walther KA, Fernandez JM (2007) Dwell-time distribution analysis of polyprotein unfolding using force-clamp spectroscopy. Biophys J 92:2896–2903

Bullard B, Ferguson C, Minajeva A, Leake MC, Gautel M, Labeit D, Ding L, Labeit S, Horwitz J, Leonard KR, Linke WA (2004) Association of the chaperone alphaB-crystallin with titin in heart muscle. J Biol Chem 279:7917–7924

Bullard B, Garcia T, Benes V, Leake MC, Linke WA, Oberhauser AF (2006) The molecular elasticity of the insect flight muscle proteins projectin and kettin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:4451–4456

Bustamante C, Marko JF, Siggia ED, Smith S (1994) Entropic elasticity of lambda-phage DNA. Science 265:1599–1600

Bustamante C, Smith SB, Liphardt J, Smith D (2000) Single-molecule studies of DNA mechanics. Curr Opin Struct Biol 10:279–285

Cao Y, Li H (2006) Single molecule force spectroscopy reveals a weakly populated microstate of the FnIII domains of tenascin. J Mol Biol 361:372–381

Carrion-Vazquez M, Oberhauser AF, Fowler SB, Marszalek PE, Broedel SE, Clarke J, Fernandez JM (1999) Mechanical and chemical unfolding of a single protein: a comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:3694–3699

Carrion-Vazquez M, Oberhauser AF, Fisher TE, Marszalek PE, Li H, Fernandez JM (2000) Mechanical design of proteins studied by single-molecule force spectroscopy and protein engineering. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 74:63–91

Carrion-Vazquez M, Li H, Lu H, Marszalek PE, Oberhauser AF, Fernandez JM (2003) The mechanical stability of ubiquitin is linkage dependent. Nat Struct Biol 10:738–743

Clausen-Schaumann H, Rief M, Tolksdorf C, Gaub HE (2000) Mechanical stability of single DNA molecules. Biophys J 78:1997–2007

Colquhoun D, Sakmann B (1981) Fluctuations in the microsecond time range of the current through single acetylcholine receptor ion channels. Nature 294:464–466

Dammer U, Hegner M, Anselmetti D, Wagner P, Dreier M, Huber W, Guentherodt H-J (1996) Specific antigen/antibody interactions measured by force microscopy. Biophys J 70:2437–2441

Dietz H, Bertz M, Schlierf M, Berkemeier F, Bornschlogl T, Junker JP, Rief M (2006) Cysteine engineering of polyproteins for single-molecule force spectroscopy. Nature Protocols 1:80–84

Erickson HP (1994) Reversible unfolding of fibronectin type III and immunoglobulin domains provides the structural basis for stretch and elasticity of titin and fibronectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:10114–10118

Evans E, Ritchie K (1997) Dynamic strength of molecular adhesion bonds. Biophys J 72:1541–1555

Fernandez JM, Li H (2004) Force-clamp spectroscopy monitors the folding trajectory of a single protein. Science 303:1674–1678

Fernandez JM (2005) Fingerprinting single molecules in vivo. Biophys J 89:3676–3677

Florin EL, Moy VT, Gaub HE (1994) Adhesion forces between individual ligand-receptor pairs. Science 264:415–417

Forbes JG, Jin AJ, Ma K, Gutierrez-Cruz G, Tsai WL, Wang K (2005) Titin PEVK segment: charge-driven elasticity of the open and flexible polyampholyte. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 26:291–301

Fowler SB, Best RB, Toca Herrera JL, Rutherford TJ, Steward A, Paci E, Karplus M, Clarke J (2002) Mechanical unfolding of a titin Ig domain: structure of unfolding intermediate revealed by combining AFM, molecular dynamics simulations, NMR and protein engineering. J Mol Biol 322:841–849

Freiburg A, Trombitás K, Hell W, Cazola O, Fougerousse F, Centner T, Kolmerer B, Witt C, Beckmann JS, Gregorio CC, Granzier H, Labeit S (2000) Series of exon-skipping events in the elastic spring region of titin as the structural basis for myofibrillar elastic diversity. Circ Res 86:1114–1121

Fukuzawa A, Hiroshima M, Maruyama K, Yonezawa N, Tokunaga M, Kimura S (2002) Single-molecule measurement of elasticity of serine-, glutamate- and lysine-rich repeats of invertebrate connectin reveals that its elasticity is caused entropically by random coil structure. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 23:449–453

Gao M, Lu H, Schulten K (2001) Simulated refolding of stretched titin immunoglobulin domains. Biophys J 81:2268–2277

Gao M, Wilmanns M, Schulten K (2002) Steered molecular dynamics studies of titin I1 domain unfolding. Biophys J 83:3435–3445

Garcia-Manyes S, Brujic J, Badilla CL, Fernandez JM (2007) Force-clamp spectroscopy of single-protein monomers reveals the individual unfolding and folding pathways of I27 and ubiquitin. Biophys J 93:2436–2446

Gautel M, Goulding D (1996) A molecular map of titin/connectin elasticity reveals two different mechanisms acting in series. FEBS Lett 385:11–14

Grama L, Nagy A, Scholl C, Huber T, Kellermayer MS (2005) Local variability in the mechanics of titin’s tandem Ig segments. Croat Chem Acta 78:405–411

Grandbois M, Beyer M, Rief M, Clausen-Schaumann H, Gaub HE (1999) How strong is a covalent bond? Science 283:1727–1730

Grandbois M, Dettmann W, Benoit M, Gaub HE (2000) Affinity imaging of red blood cells using an Atomic Force Microscope. J Histochem Cytochem 48:719–724

Granzier H, Labeit S (2007) Structure–function relations of the giant elastic protein titin in striated and smooth muscle cells. Muscle Nerve (in press), DOI 10.1002/mus.20886

Greaser M (2001) Identification of new repeating motifs in titin. Proteins 43:145–149

Gutierrez-Cruz G, Van Heerden AH, Wang K (2001) Modular motif, structural folds and affinity profiles of the PEVK segment of human fetal skeletal muscle titin. J Biol Chem 276:7442–7449

Higgins MJ, Sader JE, Jarvis SP (2006) Frequency modulation atomic force microscopy reveals individual intermediates associated with each unfolded I27 titin domain. Biophys J 90:640–647

Hille B (1992) Ionic channels of excitable membranes, 2nd edn. Sinauer, Sunderland, MA

Hinterdorfer P, Baumgartner W, Gruber HJ, Schilcher K, Schindler H (1996) Detection and localization of individual antibody-antigen recognition events by atomic force microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:3477–3481

Hutter JL, Bechhoefer J (1993) Calibration of atomic-force microscope tips. Rev Sci Instrum 64:1868–1873

Improta S, Politou AC, Pastore A (1996) Immunoglobulin-like modules from titin I-band: extensible components of muscle elasticity. Structure 4:323–337

Ingber DE (2006) Cellular mechanotransduction: putting all the pieces together again. FASEB J 20:811–827

Janovjak H, Kessler M, Oesterhelt D, Gaub H, Muller DJ (2003) Unfolding pathways of native bacteriorhodopsin depend on temperature. EMBO J 22:5220–5229

Kawakami M, Byrne K, Brockwell DJ, Radford SE, Smith DA (2006) Viscoelastic study of the mechanical unfolding of a protein by AFM. Biophys J 91:L16–18

Kellermayer MS, Smith SB, Granzier HL, Bustamante C (1997) Folding–unfolding transitions in single titin molecules characterized with laser tweezers. Science 276:1112–1116

Kellermayer MS, Smith SB, Bustamante C, Granzier HL (2001) Mechanical fatigue in repetitively stretched single molecules of titin. Biophys J 80:852–863

Kellermayer MS, Bustamante C, Granzier HL (2003) Mechanics and structure of titin oligomers explored with atomic force microscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1604:105–114

Kellermayer MS, Karsai A, Kengyel A, Nagy A, Bianco P, Huber T, Kulcsar A, Niedetzky C, Proksch R, Grama L (2006) Spatially and temporally synchronized atomic force and total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy for imaging and manipulating cells and biomolecules. Biophys J 91:2665–2677

Kessler M, Gaub HE (2006) Unfolding barriers in bacteriorhodopsin probed from the cytoplasmic and the extracellular side by AFM. Structure 14:521–527

Klimov DK, Thirumalai D (2000) Native topology determines force-induced unfolding pathways in globular proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:7254–7259

Klimov DK, Newfield D, Thirumalai D (2002) Simulations of beta-hairpin folding confined to spherical pores using distributed computing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:8019–8024

Konhilas JP, Irving TC, deTombe PP (2002) Myofilament calcium sensitivity in skinned rat cardiac trabeculae: role of interfilament spacing. Circ Res 90:59–65

Kruger M, Kohl T, Linke WA (2006) Developmental changes in passive stiffness and myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity due to titin and troponin-I isoform switching are not critically triggered by birth. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291:H496–506

Labeit D, Watanabe K, Witt C, Fujita H, Wu Y, Lahmers S, Funck T, Labeit S, Granzier H (2003) Calcium-dependent molecular spring elements in the giant protein titin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:13716–13721

Labeit S, Kolmerer B (1995) Titins: giant proteins in charge of muscle ultrastructure and elasticity. Science 270:293–296

Lahmers S, Wu Y, Call DR, Labeit S, Granzier H (2004) Developmental control of titin isoform expression and passive stiffness in fetal and neonatal myocardium. Circ Res 94:505–513

Leake MC, Wilson D, Bullard B, Simmons RM (2003) The elasticity of single kettin molecules using a two-bead laser-tweezers assay. FEBS Lett 535:55–60

Leake MC, Wilson D, Gautel M, Simmons RM (2004) The elasticity of single titin molecules using a two-bead optical tweezers assay. Biophys J 87:1112–1135

Leake MC, Grutzner A, Krueger M, Linke WA (2006) Mechanical properties of cardiac titin’s N2B-region by single molecule atomic force spectroscopy. J Struct Biol 155:263–272

Lee G, Abdi K, Jiang Y, Michaely P, Bennett V, Marszalek PE (2006) Nanospring behaviour of ankyrin repeats. Nature 440:246–249

Lee GU, Chrisey LA, Colton RJ (1994) Direct measurement of the forces between complementary strands of DNA. Science 266:771–773

Li H, Oberhauser AF, Redick SD, Carrion-Vazquez M, Erickson HP, Fernandez JM (2001) Multiple conformations of PEVK proteins detected by single-molecule techniques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:10682–10686

Li H, Linke WA, Oberhauser AF, Carrion-Vazquez M, Kerkvliet JG, Lu H, Marszalek PE, Fernandez JM (2002) Reverse engineering of the giant muscle protein titin. Nature 418:998–1002

Li H, Fernandez JM (2003) Mechanical design of the first proximal Ig domain of human cardiac titin revealed by single molecule force spectroscopy. J Mol Biol 334:75–86

Li MS, Hu CK, Klimov DK, Thirumalai D (2006) Multiple stepwise refolding of immunoglobulin domain I27 upon force quench depends on initial conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:93–98

Linke WA, Bartoo ML, Ivemeyer M, Pollack GH (1996) Limits of titin extension in single cardiac myofibrils. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 17:425–438

Linke WA, Ivemeyer M, Olivieri N, Kolmerer B, Ruegg JC, Labeit S (1996) Towards a molecular understanding of the elasticity of titin. J Mol Biol 261:62–71

Linke WA, Ivemeyer M, Mundel M, Stockmeier MR, Kolmerer B (1998) Nature of PEVK-titin elasticity in skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:8052–8057

Linke WA, Stockmeier MR, Ivemeyer M, Hosser H, Mundel P (1998) Characterizing titin’s I-band Ig domain region as an entropic spring. J Cell Sci 111:1567–1574

Linke WA, Rudy DE, Centner T, Gautel M, Witt C, Labeit S, Gregorio CC (1999) I-band titin in cardiac muscle is a three-element molecular spring and is critical for maintaining thin filament structure. J Cell Biol 146:631–644

Linke WA, Fernandez JM (2002) Cardiac titin: molecular basis of elasticity and cellular contribution to elastic and viscous stiffness components in myocardium. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 23:483–497

Linke WA, Kulke M, Li H, Fujita-Becker S, Neagoe C, Manstein DJ, Gautel M, Fernandez JM (2002) PEVK domain of titin: an entropic spring with actin-binding properties. J Struct Biol 137:194–205

Linke WA, Leake MC (2004) Multiple sources of passive stress relaxation in muscle fibres. Phys Med Biol 49:3613–3627

Linke WA (2007) Sense and stretchability: the role of titin and titin-associated proteins in myocardial stress-sensing and mechanical dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res (in press), DOI 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.029

Liversage AD, Holmes D, Knight PJ, Tskhovrebova L, Trinick J (2001) Titin and the sarcomere symmetry paradox. J Mol Biol 305:401–409

Lu H, Isralewitz B, Krammer A, Vogel V, Schulten K (1998) Unfolding of titin immunoglobulin domains by steered molecular dynamics simulation. Biophys J 75:662–671

Lu H, Schulten K (2000) The key event in force-induced unfolding of Titin’s immunoglobulin domains. Biophys J 79:51–65

Makarenko I, Opitz CA, Leake MC, Neagoe C, Kulke M, Gwathmey JK, del Monte F, Hajjar RJ, Linke WA (2004) Passive stiffness changes caused by upregulation of compliant titin isoforms in human dilated cardiomyopathy hearts. Circ Res 95:708–716

Marko JF, Siggia ED (1995) Stretching DNA. Macromolecules 28:8759–8770

Marszalek PE, Oberhauser AF, Pang YP, Fernandez JM (1998) Polysaccharide elasticity governed by chair-boat transitions of the glucopyranose ring. Nature 396:661–664

Marszalek PE, Lu H, Li H, Carrion-Vazquez M, Oberhauser AF, Schulten K, Fernandez JM (1999) Mechanical unfolding intermediates in titin modules. Nature 402:100–103

Marszalek PE, Li H, Fernandez JM (2001) Fingerprinting polysaccharides with single-molecule atomic force microscopy. Nat Biotechnol 19:258–262

Marszalek PE, Li H, Oberhauser AF, Fernandez JM (2002) Chair-boat transitions in single polysaccharide molecules observed with force-ramp AFM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:4278–4283

Mayans O, Wuerges J, Canela S, Gautel M, Wilmanns M (2001) Structural evidence for a possible role of reversible disulphide bridge formation in the elasticity of the muscle protein titin. Structure 9:331–340

Minajeva A, Kulke M, Fernandez JM, Linke WA (2001) Unfolding of titin domains explains the viscoelastic behavior of skeletal myofibrils. Biophys J 80:1442–1451

Molloy JE, Burns JE, Kendrick-Jones J, Tregear RT, White DC (1995) Movement and force produced by a single myosin head. Nature 378:209–212

Nagueh SF, Shah G, Wu Y, Torre-Amione G, King NM, Lahmers S, Witt CC, Becker K, Labeit S, Granzier HL (2004) Altered titin expression, myocardial stiffness, and left ventricular function in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 110:155–162

Nagy A, Grama L, Huber T, Bianco P, Trombitas K, Granzier HL, Kellermayer MS (2005) Hierarchical extensibility in the PEVK domain of skeletal-muscle titin. Biophys J 89:329–336

Neagoe C, Kulke M, del Monte F, Gwathmey JK, de Tombe PP, Hajjar RJ, Linke WA (2002) Titin isoform switch in ischemic human heart disease. Circulation 106:1333–1341

Neagoe C, Opitz CA, Makarenko I, Linke WA (2003) Gigantic variety: expression patterns of titin isoforms in striated muscles and consequences for myofibrillar passive stiffness. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 24:175–189

Ng SP, Rounsevell RW, Steward A, Geierhaas CD, Williams PM, Paci E, Clarke J (2005) Mechanical unfolding of TNfn3: The unfolding pathway of a fnIII domain probed by protein engineering, AFM and MD simulations. J Mol Biol 350:776–789

Oberhauser AF, Marszalek PE, Erickson HP, Ferndandez JM (1998) The molecular elasticity of the extracellular matrix protein tenascin. Nature 393:181–185

Oberhauser AF, Marszalek PE, Carrion-Vazquez M, Fernandez JM (1999) Single protein misfolding events captured by atomic force microscopy. Nat Struct Biol 6:1025–1028

Oberhauser AF, Hansma PK, Carrion-Vazquez M, Fernandez JM (2001) Stepwise unfolding of titin under force-clamp atomic force microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:468–472

Oberhauser AF, Badilla-Fernandez C, Carrion-Vazquez M, Fernandez JM (2002) The mechanical hierarchies of fibronectin observed with single-molecule AFM. J Mol Biol 319:433–447

Oesterhelt F, Oesterhelt D, Pfeiffer M, Engel A, Gaub HE, Muller DJ (2000) Unfolding pathways of individual bacteriorhodopsins. Science 288:143–146

Opitz CA, Kulke M, Leake MC, Neagoe C, Hinssen H, Hajjar RJ, Linke WA (2003) Damped elastic recoil of the titin spring in myofibrils of human myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:12688–12693

Opitz CA, Leake MC, Makarenko I, Benes V, Linke WA (2004) Developmentally regulated switching of titin size alters myofibrillar stiffness in the perinatal heart. Circ Res 94:967–975

Pabon G, Amzel LM (2006) Mechanism of titin unfolding by force: insight from quasi-equilibrium molecular dynamics calculations. Biophys J 91:467–472

Paci E, Karplus M (2000) Unfolding proteins by external forces and temperature: the importance of topology and energetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:6521–6526

Politou AS, Thomas DJ, Pastore A (1995) The folding and stability of titin immunoglobulin-like modules, with implications for the mechanism of elasticity. Biophys J 69:2601–2610

Prado LG, Makarenko I, Andresen C, Kruger M, Opitz CA, Linke WA (2005) Isoform diversity of giant proteins in relation to passive and active contractile properties of rabbit skeletal muscles. J Gen Physiol 126:461–480

Raab A, Han W, Badt D, Smith-Gill SJ, Lindsay SM, Schindler H, Hinterdorfer P (1999) Antibody recognition imaging by force microscopy. Nat Biotechnol 17:901–905

Radmacher M, Cleveland JP, Fritz M, Hansma HG, Hansma PK (1994) Mapping interaction forces with the atomic force microscope. Biophys J 66:2159–2165

Ranatunga KW (2001) Sarcomeric visco-elasticity of chemically skinned skeletal muscle fibres of the rabbit at rest. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 22:399–414

Rief M, Gautel M, Oesterhelt F, Fernandez JM, Gaub HE (1997) Reversible unfolding of individual titin immunoglobulin domains by AFM. Science 276:1109–1112

Rief M, Oesterhelt F, Heymann B, Gaub HE (1997) Single molecule force spectroscopy on polysaccharides by atomic force microscopy. Science 275:1295–1297

Rief M, Gautel M, Schemmel A, Gaub HE (1998) The mechanical stability of immunoglobulin and fibronectin III domains in the muscle protein titin measured by atomic force microscopy. Biophys J 75:3008–3014

Rief M, Clausen-Schaumann H, Gaub HE (1999) Sequence-dependent mechanics of single DNA molecules. Nat Struct Biol 6:346–349

Rief M, Pascual J, Saraste M, Gaub HE (1999) Single molecule force spectroscopy of spectrin repeats: low unfolding forces in helix bundles. J Mol Biol 286:553–561

Rief M, Rock RS, Mehta AD, Mooseker MS, Cheney RE, Spudich JA (2000) Myosin-V stepping kinetics: a molecular model for processivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:9482–9486

Sarkar A, Robertson RB, Fernandez JM (2004) Simultaneous atomic force microscope and fluorescence measurements of protein unfolding using a calibrated evanescent wave. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:12882–12886

Sarkar A, Caamano S, Fernandez JM (2007) The mechanical fingerprint of a parallel polyprotein dimer. Biophys J 92:L36–38

Schlierf M, Li H, Fernandez JM (2004) The unfolding kinetics of ubiquitin captured with single-molecule force-clamp techniques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:7299–7304

Sharma D, Cao Y, Li H (2006) Engineering proteins with novel mechanical properties by recombination of protein fragments. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 45:5633–5638

Smith ML, Gourdon D, Little WC, Kubow KE, Eguiluz RA, Luna-Morris S, Vogel V (2007) Force-induced unfolding of fibronectin in the extracellular matrix of living cells. PLoS Biol 5(e268):2243–2254

Sosnick TR (2004) Comment on “Force-clamp spectroscopy monitors the folding trajectory of a single protein”. Science 306:411

Soteriou A, Clarke A, Martin S, Trinick J (1993) Titin folding energy and elasticity. Proc Biol Sci 254:83–86

Sotomayor M, Schulten K (2007) Single-molecule experiments in vitro and in silico. Science 316:1144–1148

Stroh CM, Ebner A, Geretschlaeger M, Freudenthaler G, Kienberger F, Kamruzzahan ASM, Smith-Gill SJ, Gruber HJ, Hinterdorfer P (2004) Simultaneous topography and recognition imaging using force microscopy. Biophys J 87:1981–1990

Stroh C, Wang H, Ashcroft R, Nelson J, Gruber H, Lohr D, Lindsay SM, Hinterdorfer P (2004) Single-molecule recognition imaging microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:12503–12507

Sulkowska JI, Cieplak M (2007) Stretching to understand proteins - a survey of the protein data bank. Biophys J (in press), DOI 10.1529/biophysj.107.105973

Trombitas K, Greaser M, Labeit S, Jin JP, Kellermayer M, Helmes M, Granzier H (1998) Titin extensibility in situ: entropic elasticity of permanently folded and permanently unfolded molecular segments. J Cell Biol 140:853–859

Trombitas K, Wu Y, McNabb M, Greaser M, Kellermayer MSZ, Labeit S, Granzier H (2003) Molecular basis of passive stress relaxation in human soleus fibers: assessment of the role of Immunoglobulin-like domain unfolding. Biophys J 85:3142–3153

Tskhovrebova L, Trinick J, Sleep JA, Simmons RM (1997) Elasticity and unfolding of single molecules of the giant muscle protein titin. Nature 387:308–312

Tskhovrebova L, Houmeida A, Trinick J (2005) Can the passive elasticity of muscle be explained directly from the mechanics of individual titin molecules? J Muscle Res Cell Motil 26:285–289

Visscher K, Schnitzer MJ, Block SM (1999) Single kinesin molecules studied with a molecular force clamp. Nature 400:184–189

Walther KA, Grater F, Dougan L, Badilla CL, Berne BJ, Fernandez JM (2007) Signatures of hydrophobic collapse in extended proteins captured with force spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:7916–7921

Warren CM, Krzesinski PR, Campbell KS, Moss RL, Greaser ML (2004) Titin isoform changes in rat myocardium during development. Mech Dev 121:1301–1312

Watanabe K, Muhle-Goll C, Kellermayer MS, Labeit S, Granzier H (2002) Different molecular mechanics displayed by titin’s constitutively and differentially expressed tandem Ig segments. J Struct Biol 137:248–258

Watanabe K, Nair P, Labeit D, Kellermayer MS, Greaser M, Labeit S, Granzier H (2002) Molecular mechanics of cardiac titin’s PEVK and N2B spring elements. J Biol Chem 277:11549–11558

Williams PM, Fowler SB, Best RB, Toca-Herrera JL, Scott KA, Steward A, Clarke J (2003) Hidden complexity in the mechanical properties of titin. Nature 422:446–449

Zhang B, Evans JS (2001) Modeling AFM-induced PEVK extension and the reversible unfolding of Ig/FNIII domains in single and multiple titin molecules. Biophys J 80:597–605

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sergi Garcia-Manyes for providing the force trajectory of (I91)8 shown in Fig. 5 and Drs. Lorna Dougan, Hongbin Li, Andres Oberhauser, and Prof. Julio Fernandez for critical reading of the manuscript. We also acknowledge financial support by the DFG (SFB 629).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Linke, W.A., Grützner, A. Pulling single molecules of titin by AFM—recent advances and physiological implications. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol 456, 101–115 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-007-0389-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-007-0389-x