Abstract

Introduction

The frequency of revisional bariatric surgery is increasing, but its effectiveness and safety are not yet fully established. The aim of our study was to compare short-term outcomes of primary (pRYGB and pSG) and revisional bariatric surgeries (rRYGB and rSG).

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study assessing all patients submitted to primary and revisional (after a failed AGB) RYGB and SG in 2019. Each patient was followed-up at 6 months and 12 months after surgery. We compared pRYGB vs. rRYGB, pSG vs. rSG and rRYGB vs. rSG on weight loss, surgical complications, and resolution of comorbidities.

Results

We assessed 494 patients, of which 18.8% had undergone a revisional procedure. Higher weight loss at 6 and 12 months was observed in patients undergoing primary vs. revisional procedures. Patients submitted to rRYGB lost more weight than those with rSG (%EWL 12 months = 82.6% vs. 69.0%, p < 0.001). Regarding the resolution of obesity-related comorbidities, diabetes resolution was more frequent in pRYGB than rRYGB (54.2% vs. 25.0%; p = 0.038). Also, 41.7% of the patients who underwent rRYGB had dyslipidemia resolution vs. 0% from the rSG group (p = 0.035). Dyslipidemia resolution was also more common in pSG vs. rSG (68.6% vs. 0.0%; p = 0.001). No significant differences in surgical complications were found.

Conclusion

Revisional bariatric surgery is effective and safe treating obesity and related comorbidities after AGB. Primary procedures appear to be associated with better weight loss outcomes. Further prospective studies are needed to better understand the role of revisional bariatric surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity is a complex multifactorial disease, whose prevalence is increasing steadily in the last decades [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies obesity as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or higher, representing a health challenge. It affects almost all physiological functions of the body, and it increases the risk for developing multiple comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus type 2 (T2DM), cardiovascular disease, cancer, osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and poor mental health, thereby contributing to a decline in quality of life, work productivity as well as to increased healthcare costs [2].

Bariatric surgery is regarded as the most effective intervention for achieving substantial and long-lasting weight loss and resolution of obesity associated comorbidities, exceeding the results obtained with medical treatment [3]. The laparoscopic implantation of an adjustable gastric banding (AGB) was first described in 1993 and it became one of the most common bariatric procedures in the world [4]. Its popularity was due to the remarkable safety profile and low initial morbidity rate [5]. The AGB has a balloon which can be inflated, constricting the stomach in order to reduce the patient’s oral intake [6]. Complications of AGB were initially believed to be minor and rare. However, long-term studies have progressively shown late-onset complications that lead to revisional surgeries [5]. The high complication rate (including hardware malfunctions with the band, tubing, or access port; esophageal motility disorders; adverse gastrointestinal symptoms; and psychological intolerance to the band) negatively impacts patients’ satisfaction and quality of life [7, 8]. Moreover, a significant fraction of patients submitted to AGB fail to lose weight or have weight regain, frequently requiring conversion to other bariatric procedures [5]. Recent studies have reported long-term reoperations in 31–80% of patients following failed AGB [9].

Nowadays, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and sleeve gastrectomy (SG) are the two most commonly performed bariatric procedures [10]. RYGB has shown better outcomes regarding the resolution of obesity-related comorbidities [11, 12]. However, SG is still the most frequent bariatric surgery performed because it is technically easier and faster to perform, resulting in fewer postoperative complication and reoperation rates and in similar excess weight reduction [13, 14].

Revisional bariatric surgeries are becoming increasingly common due to inadequate weight reduction, weight regain, and postoperative morbidity [8, 15, 16]. The most successful conversion strategy relies on selecting the most appropriate revisional intervention, depending mostly on the indications for revision themselves [8]. Despite the growing demand for revisional procedures, there is still some controversy on their safety and efficacy [16]. Also, there is insufficient evidence on which procedure is more suitable for each patient. Despite the lack of standardized guidelines for the conversion strategy from AGB, RYGB and SG are the most frequent procedures applied [17].

The aim of our study is to compare short-term outcomes of primary (pRYGB and pSG) vs. revisional bariatric surgeries (rRYGB and rSG), and between different types of revisional interventions on weight loss outcomes, surgical complications, and resolution of obesity-related comorbidities.

Materials and methods

Participants and setting

This is a retrospective cohort study assessing a consecutive sample of all adult (age > 18 years) patients submitted to either primary or revisional RYGB or SG between January to December 2019 in a single tertiary hospital in Northern Portugal. We excluded patients submitted to a revisional surgery whose primary procedure was not the implantation of a laparoscopic AGB.

In our institution, all patients are evaluated multidisciplinary (surgery, endocrinology, nutrition, psychology/psychiatry, and anesthesiology) and per-protocol, all patients are submitted to extensive blood and urine analysis, upper endoscopy and abdominal ultrasonography, and eligibility criteria are defined accordingly to ASMBS and IFSO criteria. Gastric bypass is suggested for individuals dealing with hiatal hernias, GERD, or esophagitis, as well as patients with other comorbidities that will benefit from this procedure, like diabetes or psoriasis. On the other hand, sleeve gastrectomy is proposed to patients with specific diseases, like inflammatory bowel disease, and those with unamenable risk factors for gastric cancer, like persistent Helicobacter Pylori infection or familiar history of gastric cancer. Patient opinion and preferences are other important factor to take in account. Challenging cases are discussed in a multidisciplinary meeting held once a week.

Variables

From each patient, we retrieved information on demographic characteristics, obesity-related comorbidities, previous surgeries, and surgical complications. Anthropometric data, metabolic parameters and clinical outcomes, medication, and nutritional supplements from the included patients were retrospectively collected from their electronic medical charts. We reviewed the data from the preoperative period, at the date of the surgery, and postoperatively at 6 and 12 months.

The revision from AGB was a 2-step operation, consisting of band removal followed (at a subsequent date) by a conversion operation, either RYGB or SG. RYGB was performed as a standardized technique with a small gastric pouch, a biliopancreatic limb of 100 cm, and an alimentary limb of 120 cm. SG was performed using a 54-Fr Fouchet tube, sectioning the stomach from the gastric antrum to the angle of His. The choice of bariatric procedure was made individually regarding patient characteristics, comorbidities, previous treatments, preference, and surgeon recommendation.

Weight loss was quantified as the percentage of total weight loss (%TWL) and percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL). Successful weight loss after surgery was defined if patients completed the following criteria at 12 months: %TWL ≥ 20%, %EWL ≥ 50%, and BMI < 35 kg/m2. The criteria used to evaluate the resolution of T2DM, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension (HTN), and OSA were adapted from the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) consensus statement “Standardized outcomes reporting in metabolic and bariatric surgery” [18]. Improvement of psychiatric disorders, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and osteoarticular pathologies were not evaluated in our series. Postoperative early-onset complications until 90 days after the date of the surgery were also evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented with absolute frequencies and percentages and continuous variables are presented with means ± standard deviations (SD) or with medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), depending on data distribution. The Chi-Square test was used to compare categorical variables. The independent samples t-test was used for the continuous variables with a normal distribution and the Mann–Whitney U test was applied for the continuous variables which do not follow a normal distribution. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics 26® (SPPS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA) was used to perform the statistical analysis.

Results

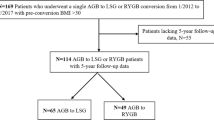

Of the 520 patients submitted to bariatric surgery in 2019 at our hospital, 494 patients met the eligibility criteria and were included in this study (Fig. 1). Ninety-three (18.8%) of the eligible participants underwent a revisional bariatric surgery after a failed AGB. RYGB was the most common bariatric procedure: 329 (66.6%) patients were submitted to RYGB, 73 (22.2%) of them were patients undergoing rRYGB. Of the 165 patients undergoing SG, 20 (12.1%) had this procedure as a revisional bariatric surgery.

The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Median age on presentation was 45.0 years for pRYGB and 49.0 for rRYGB (p = 0.001). Median age was 44.0 years for pSG vs. 51.0 years for rSG (p = 0.002). One pSG was performed as an open surgery, associated to other procedure (bowel reconstruction). As for the remaining bariatric procedures, they were done laparoscopically, not requiring conversion to open surgery. There was no mortality in either group. There were no differences regarding pre-operative BMI and pre-operative comorbidities (30 Clavien-Dindo II; 1 Clavien-Dindo IIIb). Every patient completed the 12-month follow-up of our study.

Figure 2 displays the indications for revisional bariatric surgery. Insufficient weight loss was the main reason for revisional surgery: 65 (69.9%) patients removed the AGB due to inadequate weight loss or weight regain. Slippage and other complications (17 patients; 18.8%), incoercible vomiting (8 patients; 8.6%), and refractory reflux (3 patients; 3.2%) were other indications reported in our series.

pRYGB vs. rRYGB

Weight loss outcomes are presented in Table 2. We found significant higher %TWL and %EWL and a lower BMI at 6 and 12 months in the pRYGB group. The frequency of patients reaching the qualitative criteria of %TWL ≥ 20%, %EWL ≥ 50%, and BMI < 35 kg/m2 did not differ between the two groups.

Table 3 presents the results concerning morbidity and mortality. Operative time was shorter in the pRYGB group (median: 90.00 min [IQR 76.00–109.00] vs. 117.00 min [IQR 96.75–145.50], p < 0.001). Fourteen (5.5%) patients in the pRYGB group developed postoperative complications vs. 4 (5.5%) patients in the rRYGB group (p = 1.000).

Concerning the resolution of obesity-related comorbidities, 32 of the 59 (54.2%) valid cases (with preoperative comorbidities) submitted to pRYGB and 4/ out of 16 (25.0%) patients who underwent rRYGB had a T2DM resolution (p = 0.038) (Table 4). No significant differences were observed regarding the resolution of HTN, dyslipidemia, and OSA.

pSG vs. rSG

The %TWL and %EWL at 6 and 12 months were higher in the pSG group than the rSG group. The BMI at 6 months was not statistically different between the two groups, but we found a statistically lower BMI at 12 months in the pSG group when compared to the rSG group (median: 29.45 [IQR 25.98–33.17] vs. 34.16 [IQR 29.38–36.20], p = 0.012). Also, at 12 months, 84.6% of the patients submitted to pSG had BMI < 35 kg/m2 vs. 60.0% of the rSG patients (p = 0.033). No significant differences were observed on the remaining qualitative criteria.

Operative time was longer in the rSG group (62.5 min [IQR 50.75–83.5] vs. 86.0 [IQR 59.00–129.00]; p = 0.016). Postoperative complications developed in 11 (7.6%) patients in the pSG group and 2 (10.0%) patients in the rSG group (p = 0.660).

Concerning the outcomes of comorbidities, 24 of the 35 (68.6%) valid cases in the pSG group and 0/8 (0.0%) patients in the rSG group had dyslipidemia resolution. No other significant differences were observed.

rRYGB vs. rSG

We found statistically significant higher %TWL and %EWL and a lower BMI at 6 and 12 months in the rRYGB group when compared to the rSG group. Also, 98.3% of the patients submitted to rRYGB had BMI < 35 kg/m2 vs. 60% of the rSG patients (p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed on the remaining qualitative criteria, even though results tended to favor rRYGB.

Operative time was longer in the rRYGB group (90.00 [IQR 76.00–109.00] vs. 117.00 [IQR 96.75–145.50] p = 0.020). Four (5.5%) patients in the rRYGB group and 2 (10.0%) patients in the rSG group developed postoperative complications (p = 0.606).

Concerning the resolution of obesity-related comorbidities, 10/24 (41.7%) patients submitted to rRYGB and 0/8 (0.0%) patients who underwent rSG had the resolution of dyslipidemia (p = 0.035). No significant differences were observed regarding the resolution of HTN, T2DM, and OSA.

Discussion

AGB used to be the most common bariatric surgery performed worldwide due to its technical simplicity and low surgical risk [19]. However, it has been associated with high rates of complications requiring revision [5,6,7, 20]. According to our findings, weight regain, and insufficient weight loss were the most common indications for revisional bariatric surgery, accounting for more than two-thirds of patients submitted to revisional procedures. Other studies report similar findings—in a systematic review, Magouliotis et al. reported that among patients submitted to rRYGB and rSG, two-thirds had the indication of insufficient weight loss after AGB [20].

The present study demonstrates that both rRYGB and rSG are safe procedures. We did not find any significant difference between either the primary and revisional bariatric surgery groups or between the different revisional groups on the frequency of early complications (even though revisional bariatric interventions are technically more demanding and they are usually associated with higher intraoperative and perioperative risks than primary procedures) [9, 21, 22]. The absence of significant differences concerning postoperative complications can be explained by the surgeons’ expertise and the high number of bariatric procedures performed annually at our center. It is consensual in the literature that the experience of the surgical team, as well as the hospital volume, are associated with better outcomes for bariatric surgical procedures [23]. The ASMBS recommends that these revisional procedures should only be done by experienced bariatric surgeons in health care centers with the resources to manage these challenging patients and to provide early treatment to patients who potentially develop postoperative complications [24].

We have also found an increased operation time in the revisional bariatric procedures, which is reported in several studies [21, 22, 25]. rRYGB took longer than rSG, which is in accordance with several studies [20, 26]. This difference may be explained by the fact SG is a technically easier surgical approach [14].

Regarding the weight loss outcomes, we found significant differences at 6 and 12 months between the primary and revisional groups. Patients submitted to pRYGB lost more weight and displayed a better BMI than those who underwent rRYGB. The literature is almost unanimous stating that pRYGB has better weight loss outcomes than rRYGB [27, 28].

Similar conclusions can be drawn when comparing pSG with rSG. pSG group had better weight loss outcomes than rSG. There is insufficient evidence evaluating weight loss outcomes between pSG and rSG after AGB removal, but a few studies report similar weight loss outcomes after rSG when compared to pSG [29].

There is no consensus concerning the weight loss outcomes comparing both revisional procedures. Performing SG after a failed AGB is often criticized because they are both restrictive bariatric procedures, but many others state that the excision of the gastric fundus may have endocrine effects, reducing the ghrelin levels [8, 19]. Many studies report no difference between rRYGB and rSG [26], while other studies conclude that rRYGB has better weight loss outcomes than rSG and is the most appropriate revision procedure if the primary cause for AGB removal was inadequate weight loss [8]. At 6 and 12 months, rRYGB had consistently better weight loss outcomes than rSG. Also, we found that a higher percentage of patients submitted to rRYGB reached BMI < 35 kg/m2 compared to those undergoing rSG.

It has been established that revisional bariatric surgery plays a role in the improvement and remission of obesity-related comorbidities [24]. However, whether there are differences in the improvement of comorbidities between procedures is still controversial—most of the studies indicate that pRYGB is associated with higher improvement of comorbidities, [30, 31] but other studies found similar rates between pRYGB and rRYGB regarding obesity-related diseases’ resolution [27, 32]. In this study, we found that pRYGB was associated with significantly higher frequency of T2DM resolution, but such was not observed for other comorbidities. Similarly, we observed higher frequency of dyslipidemia resolution with pSG compared to rSG, but no significant differences were observed for other comorbidities. However, these results should be analyzed with caution, given that different indications are used for each procedure.

There is shortage of quality data in the literature comparing revisional procedures concerning resolution of preoperative comorbidities [33]. Although many studies draw recommendations of which revisional surgery is more appropriate based on the primary cause for AGB removal, there are few studies addressing which one is better for the treatment of obesity comorbidities. Our series showed better outcomes regarding the resolution of dyslipidemia in rRYGB patients than those who were submitted to rSG.

The results regarding resolution of obesity-related comorbidities must be interpreted with caution because there is a substantial number of cases missing, since our follow-up period included the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, with many appointments being done by phone. It was difficult to accurately assess if the patients found the criteria to establish resolution of comorbidities.

Limitations of our work include its retrospective nature. This study was performed in a single institution. Nonetheless, this assures homogeneity in treatment plan, because all patients were evaluated and treated by the same multidisciplinary team. Furthermore, with a short follow-up time, it is difficult to extrapolate long-term outcomes. Also, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, some follow-up consultations were accomplished remotely by telephone. Hence, this study cannot be used to draw conclusions about the long-term expected weight loss or comorbidities’ resolution after revisional bariatric surgery without additional longitudinal study.

Conclusion

Revisional bariatric surgery is a safe and effective option to treat obesity and related comorbidities. Our study showed poorer weight loss outcomes of revisional compared to primary RYGB and SG. RYGB was associated with better outcomes compared to SG concerning weight reduction when they are both used as conversion strategies following failed AGB. rSG is less effective than pSG and rRYGB on dyslipidemia’s resolution. The choice of the most suitable primary procedure for each patient is of paramount importance. Further clinical studies, with a prospective design and longer follow-up, are necessary to better understand the role of revisional bariatric surgery in the treatment of obesity.

Data Availability

All the data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Blüher M (2019) Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 15:288–298

Chooi YC, Ding C, Magkos F (2019) The epidemiology of obesity. Metabolism 92:6–10

Phillips BT, Shikora SA (2018) The history of metabolic and bariatric surgery: development of standards for patient safety and efficacy. Metabolism 79:97–107

Furbetta N, Cervelli R, Furbetta F (2020) Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, the past, the present and the future. Ann Transl Med 8:S4

Snow JM, Severson PA (2011) Complications of adjustable gastric banding. Surg Clin North Am 91:1249–1264 (ix)

Beitner M, Kurian MS (2012) Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Abdom Imaging 37:687–689

Matlach J, Adolf D, Benedix F, Wolff S (2011) Small-diameter bands lead to high complication rates in patients after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg 21:448–456

Switzer NJ, Karmali S, Gill RS, Sherman V (2016) Revisional bariatric surgery. Surg Clin North Am 96:827–842

Fournier P, Gero D, Dayer-Jankechova A et al (2016) Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for failed gastric banding: outcomes in 642 patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis 12:231–239

Salminen P, Helmiö M, Ovaska J et al (2018) Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: the SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 319:241–254

Han Y, Jia Y, Wang H et al (2020) Comparative analysis of weight loss and resolution of comorbidities between laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on 18 studies. Int J Surg 76:101–110

Wang FG, Yan WM, Yan M, Song MM (2018) Outcomes of Mini vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Int J Surg 56:7–14

Peterli R, Wölnerhanssen BK, Peters T et al (2018) Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 319:255–265

Brethauer SA (2011) Sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Clin North Am 91:1265–1279 (ix)

Kellogg TA (2011) Revisional bariatric surgery. Surg Clin North Am 91:1353–1371 (x)

Qiu J, Lundberg PW, Javier Birriel T et al (2018) Revisional bariatric surgery for weight regain and refractory complications in a single MBSAQIP accredited center: what are we dealing with? Obes Surg 28:2789–2795

Ma P, Reddy S, Higa KD (2016) Revisional bariatric/metabolic surgery: what dictates its indications? Curr Atheroscler Rep 18:42

Brethauer SA, Kim J, el Chaar M et al (2015) Standardized outcomes reporting in metabolic and bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 11:489–506

Pujol Rafols J, Al Abbas AI, Devriendt S et al (2018) Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or one anastomosis gastric bypass as rescue therapy after failed adjustable gastric banding: a multicenter comparative study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 14:1659–1666

Magouliotis DE, Tasiopoulou VS, Svokos AA et al (2017) Roux-En-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy as revisional procedure after adjustable gastric band: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 27:1365–1373

Zhang L, Tan WH, Chang R, Eagon JC (2015) Perioperative risk and complications of revisional bariatric surgery compared to primary Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc 29:1316–1320

Janik M, Ibikunle C, Khan A, Aryaie AH (2021) Safety of single stage revision laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy compared to laparoscopic Roux-Y gastric bypass after failed gastric banding. Obes Surg 31:588–596

Torrente JE, Cooney RN, Rogers AM, Hollenbeak CS (2013) Importance of hospital versus surgeon volume in predicting outcomes for gastric bypass procedures. Surg Obes Relat Dis 9:247–252

Brethauer SA, Kothari S, Sudan R et al (2014) Systematic review on reoperative bariatric surgery: American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Revision Task Force. Surg Obes Relat Dis 10:952–972

Clapp B, Harper B, Dodoo C et al (2020) Trends in revisional bariatric surgery using the MBSAQIP database 2015–2017. Surg Obes Relat Dis 16:908–915

Sharples AJ, Charalampakis V, Daskalakis M et al (2017) Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after revisional bariatric surgery following a failed adjustable gastric band. Obes Surg 27:2522–2536

Axer S, Szabo E, Näslund I (2017) Weight loss and alterations in co-morbidities after revisional gastric bypass: a case-matched study from the Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry. Surg Obes Relat Dis 13:796–800

Vallois A, Menahem B, Le Roux Y et al (2019) Revisional Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a safe surgical opportunity? Results of a case-matched study. Obes Surg 29:903–910

Alqahtani AR, Elahmedi M, Alamri H et al (2013) Laparoscopic removal of poor outcome gastric banding with concomitant sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg 23:782–787

Mohos E, Jánó Z, Richter D et al (2014) Quality of life, weight loss and improvement of co-morbidities after primary and revisional laparoscopic Roux Y gastric bypass procedure—comparative match pair study. Obes Surg 24:2048–2054

Navez J, Dardamanis D, Thissen JP, Navez B (2015) Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: comparison of primary versus revisional bypass by using the BAROS score. Obes Surg 25:812–817

Thereaux J, Corigliano N, Poitou C et al (2015) Five-year weight loss in primary gastric bypass and revisional gastric bypass for failed adjustable gastric banding: results of a case-matched study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 11:19–25

Yan J, Cohen R, Aminian A (2017) Reoperative bariatric surgery for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Surg Obes Relat Dis 13:1412–1421

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the Obesity Integrated Responsibility Unit (CRI-O) group members.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HSS, JN - Data colection; Concept; manuscript writing and revision; Statistical analysis LL; MNC; FAC - Data colection; manuscript revision FR; ACP; JP - Manuscript revision; concept BSP - Manuscript revision SC; ELC - Manuscript revision; concept

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the local medical ethics committee (number 46–21); no individual informed consent was necessary.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key points

• Revisional bariatric surgeries are becoming increasingly frequent.

• Revisional RYGB and SG showed poorer weight loss outcomes when compared to primary RYGB and SG, respectively.

• RYGB has better weight loss outcomes than SG when they are used as revisional bariatric procedures.

Hugo Santos-Sousa and Jorge Nogueiro contributed equally and should be considered first authors.

Authors Silvestre Carneiro and Eduardo Lima-da-Costa should both be considered senior authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Santos-Sousa, H., Nogueiro, J., Lindeza, L. et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy as revisional bariatric procedures after adjustable gastric banding: a retrospective cohort study. Langenbecks Arch Surg 408, 441 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-023-03174-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-023-03174-y