Abstract

Background

Postoperative hernia-repair complications are frequent in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). This fact challenges surgeons’ decision about hernia mesh management in these patients. Therefore, we systematically reviewed the hernia mesh repair in IBD patients with emphasis on risk factors for postoperative complications.

Method

A systematic review was done in compliance with the PRISMA guidelines. A search was carried out on PubMed and ScienceDirect databases. English language articles published from inception to October 2021 were included in this study. MERSQI scores were applied along with evidence grades in agreement with GRADE’s recommendations. The research protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021247185).

Results

The present systematic search resulted in 11,243 citations with a final inclusion of 10 citations. One paper reached high and 4 moderate quality. Patients with IBD exhibit about 27% recurrence after hernia repair. Risk factors for overall abdominal septic morbidity in Crohn’s disease comprised enteroprosthetic fistula, mesh withdrawals, surgery duration, malnutrition biological mesh, and gastrointestinal concomitant procedure.

Conclusion

Patients with IBD were subject, more so than controls to postoperative complications and hernia recurrence. The use of a diversity of mesh types, a variety of position techniques, and several surgical choices in the citations left room for less explicit and more implicit inferences as regards best surgical option for hernia repair in patients with IBD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Altogether, 2.5 million residents in Europe and 1 million in the USA are projected to have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in a near future; IBD is on the rise also in Asia, South America, and Middle East constituting a global burden [1]. IBD comprises Crohn’s disease (CD) with an incidence of 3 to 20 cases per 100,000 [2, 3] as well as ulcerative colitis (UC) with an incidence of 9 to 20 cases per 100,000 persons per year [4]. Pre-existing IBD predicts further hernia surgery [5].

An abdominal wall hernia is a weakness in the muscles of the abdominal wall through which a portion of organ or tissue can protrude and an incisional hernia (IH) after abdominal surgery is a frequent complication following laparotomy. Surgical repair of hernia is recommended for circumvention of complications and symptoms. This is the only absolute treatment, which can be done through an open or laparoscopic approach and with possible use of mesh prothesis. Abdominal and IH repair with primary suturing have a higher recurrence rate than mesh repair [6]. Yet, the use of mesh as a foreign body can lead to complications in forms of pain, infection, fistula, bowel injury, and bowel adhesions [7]. So far, newer models of mesh products have evolved over time, and an increased attention is directed towards their manufacturer for avoidance of product-related adverse complications after hernia repair.

Furthermore, patients with IBD are at risk for intestinal difficulties like obstruction, bowel perforation, fistula, toxic megacolon, and infective flares [8]. As the risk of postoperative hernia-repair complications is high, the surgeon’s decision for mesh management for patients with IBD constitutes a factual challenge in clinical practice. We aimed to systematically review the outcomes of hernia repairs in patients with IBD. We concentrated on correlations of risk factors and postoperative complications with hernia recurrence.

Methods

Protocol

The research protocol was registered with PROSPERO register for systematic reviews (CRD42021247185). A systematic review was performed in compliance with the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis) guidelines [9] along with GRADE recommendations [10, 11].

Search strategy

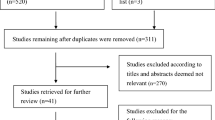

A literature search was carried out on PubMed and ScienceDirect for articles published from inception to October 2021 (Fig. 1). Search terms used were chosen from the list of MeSH (Medical Subject Headings). The search algorithm used were mesh term for Crohn’s disease and surgical mesh, ulcerative colitis and surgical mesh, inflammatory bowel disease and surgical mesh, Crohn’s disease and hernia, ulcerative colitis and hernia, and inflammatory bowel disease and hernia.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Citations directly related to abdominal hernia repair with mesh in patients with inflammatory bowel disease were included in this study.

Studies that did not clearly provided information about the mesh related complications/safety in patients with inflammatory bowel disease were excluded. Conference abstracts, letters, editorials, commentaries, protocols, experimental animal trials, and non-English publications were excluded.

Quality assessment

The retrieved citations were read in full text for further assessment for eligibility. Quality assessments and quality of studies were applied using The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) [12] which contains 10 items that reflect 6 domains of study quality including study design, sampling, type of data, validity, level of data analysis, and outcomes. For the assessment of the validity of evaluation instrument, we focused on face validity, limitations, and correlations with other instruments. The MERSQI score represents the mean of two independent assessors’ quality estimations of each citation. MERSQI produces a maximum score of 18 with a potential range from 5 to 18. The maximum score for each domain was 3. The mean quality score was calculated to be 13.83 (SD = 1.46) = moderate quality score of citation ~ 0.14. High-quality score was M + 1 SD ~ 15.5 and low-quality score was M-1 SD ~ 12.5. Very low quality was M-2 SD ~ 11.

Evidence grading

Quality of evidence for grading the studies was based on the principles elaborated by GRADE. Consequently, the evidence grading was based on criteria for using GRADE, comprising four grades:

-

Evidence grade I: strong scientific evidence based on at least 2 studies with high evidential value or a systematic review/meta-analysis with high evidential value

-

Evidence grade II: moderate scientific basis: a study with high evidential value and at least 2 studies with moderate evidential value

-

Evidence grade III: low scientific evidence: a study with high evidential value or at least 2 studies with moderate evidence value

-

Evidence grade IV: insufficient scientific evidence: 1 study with moderate evidence and/or at least 2 studies with low evidential value

Risk of bias within and across studies

We decreased the risk of bias by assessing quality in a blind manner by two authors, independently. If the assessment scores did not agree, we calculated the mean of the given scores. The calculated interrater reliability was significant (p < 0.001). We controlled for accumulated risk of bias by calculating and grading the body of evidence of the findings by determining the limits of the four grades by taking the sample’s mean score M as we maintain a moderate confidence about the result’s effect (II). Then we determined M ± 1 SD for a higher level of confidence in the effect (I) as oppose to taking M-1 SD for a lower level of confidence in the effect (III) and finally M-2SD indicated a very low confidence in the effect (IV) (Cf 12). The effect refers to the best result of the use of a certain type of technique for repair of hernia in patients with IBD. The risk of bias was likewise reduced by exclusion of citations with evidence grades III and IV in the grading, i.e., only citations of high (I) and moderate (II) quality were included in the final result.

Results

Citation selection and characteristics

The present systematic search resulted in 11,243 citations, out of which relevant citations were extracted after scanning their titles and abstracts (Fig. 1). The inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied and duplicated citations were excluded. A final 10 citations were suitable relative to the research rational and the articles’ full texts were read for further evaluation. The mean number of years was 11.1 years (SD 10.71 years), ranging from 1 to 38 years. The interrater reliability for quality assessment was rs = 0.94; p < 0.001. The tabular analysis of the citations for patients with IBD is presented in Table 1 which comprises details about studies, journals, quality scores and evidence grades of the studies. Furthermore, the citations’ aims, kind of hernia, hernia-repair technique, type of mesh, findings, and complications are described [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

Results of quality and evidence-grade assessments

Out of 10 citations, one reached high quality (grade I), 4 moderate quality (grade II), 4 low quality (grade III), and 1 very low quality (grade IV). Papers with evidence grades I and II were considered for evidence-based outcome. The evidence grades were determined as follows: I high quality = 13.83 + 1.46 = 15.29 = 15.5; II moderate quality = 13.83 = 14; III low quality = 12.37 = 12.5; IV very low quality = M-2SD = 10.91 = 11. The difference between I and II and III and IV was significant (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Results of individual studies

Beyer-Berjot et al. [13] assessed the risk of septic morbidity (SM) in patients with CD after mesh repair for ventral hernia (VH). The study was a 1:1 matched case–control analysis and elective mesh repair for VH was performed. Controls were non-IBD. All kinds of VH repair involving mesh positioning were included. Absorbable, permanent synthetic or biological mesh and thread or tacker mesh fixation were involved. The mesh was positioned as intraperitoneal onlay (IPOM) or sublay in a laparoscopic or open approach. No heavy weight mesh was used. Only type I with pores larger than 75 microns were employed, whether with polypropylene, composite polypropylene and ePTFE, and composite polypropylene and hydrogel or polyester.

Abdominal septic morbidity (ASM) connected to hernia repair, indicated inflamed skin, acute leaking, fistula or abscess in subcutaneous or peri-prosthetic space and fever (38.5 °C) with no other causes. ASM occurred in 21 out of 114 CD patients; 11 patients experienced short-term ASM with wound (7%) or intra-abdominal sepsis (2.6%) with two reoperations and one CT-guided drainage. After follow-up, 12 patients experienced chronic mesh infection, including 8 intestinal fistulas with mesh involvement and late reoperations in 9 cases and mesh withdrawal in 6 cases. Fourteen patients underwent reoperation for CD recurrence. Risk factors for ASM in CD patients were malnutrition, midline incision site of hernia, biological mesh, and digestive concomitant procedure. The B3 phenotype, anti-TNF therapy, and corticosteroids were not associated with a higher risk of postoperative sepsis.

The mesh was permanent synthetic in 95 CD patients vs. 109 controls, absorbable in 6 CD patients vs. 7 controls, and biological in 11 CD patients vs. 4 controls. Short-term severe postoperative morbidity was similar in CD and control groups but CD patients were at higher susceptibility of abdominal SM, both short-term and long-term as well as at risk of entero-prosthetic fistula and mesh withdrawals, more so than controls. Hernia recurrence was similar in both groups. No patient died but CD is a risk factor for SM after mesh repair in VH.

Heimann et al. [14] studied 1000 patients with IBD undergoing open bowel resection. Of these, 203 developed IH and outcomes of 170 patients with IBD, who underwent IH repair, are reported in the study; 92 suffered from UC and 78 patients endured CD. The use of mesh, its placement, and incidence of post-operative complications were similar in both groups. Patients with CD had higher rate of bowel resection and/or presence of ileostomy during hernia repair.

Sixty-one patients had IH repair with onlay synthetic mesh. One patient underwent mesh infection, removal of mesh and complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Thirty-one patients had inlay synthetic mesh repair and 1 UC and 2 CD developed late-onset enterocutaneous fistula 3–7 years postoperatively requiring reoperation, bowel resection, and removal of mesh. Hernia recurrence after IH repair was found in 46 cases; 38 patients underwent a second IH repair out of whom 10 recurred again and needed further surgery. Patients with UC undergoing primary repair had a higher recurrence rate than those enduring mesh repair. Patients with CD had similar recurrence rates for primary IH repair while those undergoing mesh repair had a higher rate of recurrence than patients with UC.

It was found that number of previous bowel resections, primary repair, use of biological mesh for reconstruction, postoperative complications, septic complications, and postoperative wound infection correlated with a higher recurrence of hernia after IH repair. Yet, the only significant independent predictor by means of multivariate statistics for recurrence of hernia after IH repair was the number of previous bowel resections.

After IH repair, about 27% of patients relapsed. IBD patients with second repair also had a recurrence rate of 26%. Similar rates have been reported for non-IBD patients. In sum, the number of previous bowel resections, primary repair, use of biological mesh, postoperative complications, septic complications, and postoperative wound infection correlated with recurrence of hernia after IH repair. Multiple bowel resections lead to recurrent IH. The use of synthetic mesh for IH repair in UC decreased recurrence rate. In patients with CD, synthetic mesh did not improve the recurrence rate over primary repair. Inlay synthetic mesh for IH repairs in patients with IBD has a potentially higher risk for late-onset enterocutaneous fistula.

Heise et al. [15] disclosed that patients with IBD have a high life-time risk for abdominal surgery and incisional hernias (IH). The postoperative course was studied of non-IBD (n = 199) vs. IBD (n = 34) patients with IH repair: 15 patients presented UC and 19 presented CD. The IH repair consisted of open ventral hernia repair (OVHR) with mesh augmentation in sublay position in form of PVDF on peritoneum and posterior rectus sheath.

The perioperative data revealed in IBD group compared to controls, higher rates of intraoperative blood transfusions, major complications, and postoperative relaparotomies.

During follow-up, hernia recurrence occurred in 9 IBD patients (almost 27%). An association of UC, history of more than 1 bowel resection, and extraintestinal manifestation with occurrence of recurrent hernia were found. UC was recognized as associated with IH recurrence, more so than CD patients. Patients with IBD showed higher rates of major complications after OVHR, but incidence of overall complications was not elevated compared to those non-IBD patients. By means of multivariate binary regression, the presence of IBD (HR = 4.19, p = 0.007) was the single independent predictor of major postoperative morbidity (Tables 1 and 2).

Horesh et al. [16] studied 26 out of 5467 IBD patients in their institution; 14 suffered from CD and 12 patients from UC. This cohort endured IH repair and was matched to 76 controls who also experienced IH. Patients with CD had larger hernia defects (> 5 cm) than those with UC.

Prolene mesh was employed to reconstruct the inguinal canal and to close the hernia site defect. There was no significant difference between number of patients with CD and UC who underwent laparoscopic or open surgery.

Postoperative complications followed in 8 patients: three wound infections and one postoperative seroma. One patient needed reoperation due to bowel obstruction. Hernia recurrence happened in two patients during follow-up. Postoperative complication rates were higher in IBD patients compared to those non-IBD undergoing IH repair. However, open IH repair showed similar recurrence rates when compared to laparoscopic repair. Surgery duration correlated significantly with postoperative-morbidity risk. Gastroenterologists’ and surgeons’ awareness of increased risk for surgical complications in patients with IBD patients is required.

Synthesis of results

The summery of risks and post-surgery complications in patients undergoing hernia repair as well as significant differences in results between patients with IBD and their controls is presented in Table 2. In general, ~ 27% of patients with IBD were subject to hernia recurrence after hernia repair had a mean of 36 (range 36–56) months of follow-up time.

Discussion

We systematically reviewed outcomes of hernia repairs in patients with IBD with emphasis on consequences for postoperative complications. After assessing citations with high and moderate quality, four citations formed in combination a base for moderate evidence for our results. We focused on findings based on univariate and multivariate significant factors leading to recurrent hernia repair and post-surgery complications in patients with IBD. In these patients, corticosteroids and anti-TNF agents have been associated with increased overall postoperative infection risk as well as intra-abdominal infection [23]. In addition, mesh contact with an inflamed bowel in hernia repair can cause complications such as adhesions, intestinal obstructions, and enterocutaneous fistulae.

Different types of mesh were used in our study. Two out of four citations considered biologic mesh a risk factor for complications in post-hernia repair. However, Beyer-Berjot et al. used absorbable, permanent synthetic, or biologic mesh with fixation either by threads or tackers [13]. Only type I with pores larger than 75 microns was employed, whether with polypropylene, composite polypropylene, and ePTFE as well as in composite polypropylene and hydrogel or polyester. The researchers concluded that biologic mesh should be avoided. Heimann et al. used biologic and synthetic mesh and onlay as well as sublay mesh repair were applied [14]. Yet, biologic mesh was found to be a risk factor for complications. Our finding agreed with those of a previous study that claimed that while biologic mesh is derived from decellularized human, bovine, and porcine tissue, it constitutes in its final form a collagen matrix, which impacts biocompatibility, foreign body response, and immunogenic potential of the graft [24]. Researchers also found that biologic and biosynthetic mesh should not be used in a bridging situation [25] and did not reveal any explicit advantages of biologic and biosynthetic meshes in inguinal hernia repair. Furthermore, no evidence was revealed for the use of biologic or biosynthetic meshes in the prevention of incisional and parastomal hernias.

The technique of mesh placement has continuously been debatable, based on the patient’s condition and surgeon’s preference. Beyer-Berjot et al.’s mesh was positioned as IPOM or sublay [13]. Heise et al. used polyvinylidene fluoride PVDF-mesh which was placed in sublay position on peritoneum and posterior rectus sheath [15]. This is a textile-based German mesh with a hernia recurrence was 26.5% in patients with IBD. Horesh et al. used prolene (polypropylene) mesh, which is the most common type of synthetic hernia mesh [16]. It is made from plastics and may reduce the chances of a hernia recurrence. It has previously been evidenced that permanent synthetic mesh when placed in an extraperitoneal position is safe for VHR in a contaminated field along with conferring a significantly lower rate of surgical site infection and recurrence compared to those biologics or bioabsorbable meshes [26]. In complex abdominal wall hernia repair with incarcerated hernia, parastomal hernia, infected mesh, open abdomen, entero-cutaneous fistula, and component separation technique, it has been indicated that biologic and biosynthetic meshes were not superior to synthetic meshes [25]. It is advisable to avoid placement of mesh in direct contact with the bowel, especially in patients with IBD.

Different types of hernia-repair techniques used for patients with IBD undergoing such repair also varied from citation to citation. As regard surgical technique for patients with IBD, a previous study claimed that with growing expertise in laparoscopic surgery, the minimally invasive approach is at least comparable to the open access surgery as regards long-term outcome in patients with CD [27]. Heimann et al.’s patients were subject to a laparoscopic or open approach with no difference between those with CD and UC. Heise et al.’s patients with IBD were all subject to an IH performed as an OVHR. Out of Horesh et al.’s patients with IBD, 61.5% were subject to an open approach of inguinal hernia repair. In other words, both laparoscopic and open approaches were applied for hernia repair. The current trends in laparoscopic surgery for UC were previously reviewed [28] and it was found that, although laparoscopic surgery sometimes requires a longer operation, it provides better short-term benefits compared to open surgery comprising shorter hospital stays and fasting times, as well as better cosmesis. The long-term benefits of laparoscopy include better fecundity in young females. Some surgeons favor laparoscopic surgery even for severe acute colitis due to fewer postoperative complications compared to open.

One of Beyer-Berjot’s risk factors for post-surgery complications in form of septic morbidity was malnutrition in accordance with results from a previous research that showed that poor nutrition significantly increased the risk of infectious complications such as anastomotic leak, intra-abdominal abscess, enterocutaneous fistula, or wound infection in patients with IBD [29]. Heimann et al. indicated that number of bowel resections prior to hernia repair predicted recurrence of IH [14]. It has also been found that the incidence of IH was 21% for patients with UC and 20% for patients with CD. Statistically significant risk factors for development of IH were among others, wound infection, and a history of previous bowel resection. Hernia recurrence did not differ between an open vs. laparoscopic approach in patients with IBD [30]. However, hernia recurrence is a time-dependent process [31]; Heise et al. found that IBD patients displayed a hernia recurrence rate of about 27% during a follow-up of 36 months. Heimann et al. did their follow-up during 56 months also with 27% hernia recurrence. Furthermore, IBD stands as a significant risk per se for major postoperative morbidity after OVHR. In addition, individuals with IBD show high rates of hernia recurrence over time with UC patients being more prone to recurrence than patients with CD. Horesh et al.’s postoperative complications in patients with IBD were 30.7% vs 11.8% in controls. Yet, only 2 out of 26 patients with IBD had hernia recurrence.

The study is limited by the fact that only a few citations were available in our final selection and their retrospective long-term data sampling (e.g., 38 years) nature did not reach high quality and evidence grade 1. During such a long time, a substantial mesh development takes place and continuous improvement in material and techniques are expected to better fit the hernia-repair needs for patients with IBD.

Mesh-defect-area-ratio, fixation techniques, tissue elasticity, and the hernia size under pressure can be subject for future studies for the repair of large, recurrent, and complex incisional hernia in IBD patients [32]. In addition to the possible use of tools for risk stratification, e.g., using the CEDAR app [33]. There is also claimed to be a difference in hernia-repair recurrence between patients with CD and UC, a subject that needs more clarification in future research.

Conclusion

Patients with IBD were subject, more so than controls, to postoperative complications and hernia recurrence. The use of a diversity of mesh types, a variety of position techniques, and several surgical choices in the citations left room for less explicit and more implicit interpretations as regards best surgical option for hernia repair in patients with IBD.

Change history

03 October 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-022-02699-y

References

Kaplan GG (2015) The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 12:720–727

Dahlhamer JM, Zammitti EP, Ward BW, Wheaton AG, Croft JB (2016) Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease among adults aged 18 years United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65(42):1166–1169

Feuerstein JD, Cheifetz AS (2017) Crohn disease: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Mayo Clin Proc 92(7):1088–1103

Lynch WD, Hsu R (2022) Ulcerative Colitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459282/. Accessed January 2022

Hodgkinson JD, Worley G, Warusavitarne J, Hanna GB, Vaizey CJ, Faiz OD (2021) Evaluation of the Ventral Hernia Working Group classification for long-term outcome using English Hospital Episode Statistics: a population study. Hernia 25(4):977–984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-021-02379-8

Anthony T, Bergen PC, Kim LT (2000) Factors affecting recurrence following incisional herniorrhaphy. World J Surg 24:95–100

Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK (2005) Mesh-related infections after hernia repair surgery. Clin Microbiol Infect 11:3–4

Marrero F, Qadeer MA, Lashner BA (2008) Severe complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Med Clin North Am. 92(3):671–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2007.12.002 (ix)

Stewart LA, Clarke MC, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, Tierney JF (2015) Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data the PRISMA-IPD statement. JAMA 313(16):1–1665. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3656

Schünemann H, Guyatt G, Oxman A Criteria for applying or using GRADE, GRADE Working Group, 2016 [cited 2017 May 6]. Available from: http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/docs/Criteria_for_using_GRADE_2016–04–05.pdf

Balshema H, Helfanda M, Schunemannc HJ, Oxmand AD, Kunze R, Brozekc J et al (2011) GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 64:401–406

Reed DA, Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Levine RB, Kern DE, Wright SM (2007) Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA 298(9):1002–1009

Beyer-Berjot L, Moszkowicz D, Bridoux V et al (2020) Mesh repair in Crohn’s disease: a case-matched multicenter study in 234 patients. World J Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05436-y

Heimann TM, Swaminathan S, Greenstein AJ, Greenstein AJ, Steinhagen RM (2017) Outcome of incisional hernia repair in patients with inflammatory bowel Disease. Am J Surg 214:468–473

Heise D, Schram C, Eickhoff R, Bednarsch J, Helmedag M, Schmitz SM, Kroh A, Klink CD, Neumann UP (2021) Lambertz A Incisional hernia repair by synthetic mesh prosthesis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a comparative analysis. BMC Surg 21(1):353. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-021-01350-9

Horesh N, Mansour A, Simon D, Edden Y, Klang E, Barash Y, Ben-Horin S, Kopylov U (2021) Postoperative outcomes following inguinal hernia mending in inflammatory bowel disease patients compared to matched controls. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 33(4):522–526. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000001936

Wang J, Majumder A, Fayezizadeh M, Criss CN, Novitsky YW (2016) Outcomes of retromuscular approach for abdominal wall reconstruction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am Surg 82(6):565–570

Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM, Reines HD, DeMaria EJ, Newsome HH, Lowry JW (1996) Greater risk of incisional hernia with morbidly obese than steroid dependent patients and low recurrence with prefascial polypropylene mesh. Am J Surg 171:80–84

Aycock J, Fichera A, Colwel AJ, Song DH (2007) Parastomal hernia repair with acellular dermal matrix. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 34(5):521–523

Taner T, Cima RR, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG (2009) The use of human acellular dermal matrix for parastomal hernia repair in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a novel technique to repair fascial defects. Dis Colon Rectum 52(2):349–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819a3e69

Maman D, Greenwald D, Kreniske J, Royston A, Powers S, Bauer J (2012) Modified Rives-Stoppa technique for repair of complex incisional hernias in 59 patients. Ann Plast Surg 68:190–193

Perlmutter BC, Alkhatib H, Lightner AL, Fafaj A, Zolin SJ, Petro CC, Krpata DM, Prabhu AS, Holubar SD, Rosen MJ (2021) Short-term outcomes and healthcare resource utilization following incisional hernia repair with synthetic mesh in patients with Crohn’s disease. Hernia 25:1557–1564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-021-02476-8

Law CCY, Koh D, Bao Y, Jairath V, Narula N (2020) Risk of postoperative infectious complications from medical therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 26(12):1796–1807. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izaa020

FitzGerald JF, Kumar AS (2014) Biologic versus synthetic mesh reinforcement: what are the pros and cons? Clin Colon Rectal Surg 27(4):140–148. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1394155

Köckerling F, Alam NN, Antoniou SA, Daniels IR, Famiglietti F, Fortelny RH et al (2018) What is the evidence for the use of biologic or biosynthetic meshes in abdominal wall reconstruction? Hernia 22(2):249–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1735-y

Warren J, Desai SS, Boswell ND, Hancock BH, Abbad H, Ewing JA et al (2020) Safety and efficacy of synthetic mesh for ventral hernia repair in a contaminated field. Am Coll Surg 230(4):405–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.12.008

Hoffmann M, Siebrasse D, Schlöricke E, Bouchard R, Keck T, Benecke C (2017) Long-term outcome of laparoscopic and open surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. Open Access Surg 10:45–54. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAS.S142112

Hata K, Kazama S, Nozawa H et al (2015) Laparoscopic surgery for ulcerative colitis: a review of the literature. Surg Today 45:933–938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-014-1053-7

Yamamoto T, Shimoyama T, Umegae S, Kotze PG (2019) Impact of preoperative nutritional status on the incidence rate of surgical complications in patients with inflammatory bowel disease with vs without preoperative biologic therapy: a case-control study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 10(6):e00050. https://doi.org/10.14309/ctg.0000000000000050

Heimann TH, Swaminathan S, Greenstein AJ, Steinhagen RM (2018) Incidence and factors correlating with incisional hernia following open bowel resection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a review of 1000 patients. Ann Surg 267(3):532–536. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002120

Köckerling F, Koch A, Lorenz R, Schug-Pass C, Stechemesser B, Reinpold W (2015) How long do we need to follow-up our hernia patients to find the real recurrence rate? Front Surg 16(2):24. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2015.00024)

Kallinowski F, Gutjahr D, Harder F, Sabagh M, Ludwig Y, Lozanovski VJ, Löffler T, Rinn J, Görich J, Grimm A, Vollmer M, Nessel R (2021) The grip concept of incisional hernia repair-dynamic bench test, CT abdomen with valsalva and 1-year clinical results. Front Surg 8:602181. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2021.602181

Augenstein V, Colavita PD, Wormer BA et al (2015) CeDAR: carolinas equation for determining associated risks. Am Coll Surg 221:S65–S66

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El Boghdady, M., Ewalds-Kvist, B.M. & Laliotis, A. Abdominal hernia mesh repair in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg 407, 2637–2649 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-022-02638-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-022-02638-x