Abstract

Purpose

While liver resection is a well-established treatment for primary HCC, surgical treatment for recurrent HCC (rHCC) remains the topic of an ongoing debate. Thus, we investigated perioperative and long-term outcome in patients undergoing re-resection for rHCC in comparative analysis to patients with primary HCC treated by resection.

Methods

A monocentric cohort of 212 patients undergoing curative-intent liver resection for HCC between 2010 and 2020 in a large German hepatobiliary center were eligible for analysis. Patients with primary HCC (n = 189) were compared to individuals with rHCC (n = 23) regarding perioperative results by statistical group comparisons and oncological outcome using Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Results

Comparative analysis showed no statistical difference between the resection and re-resection group in terms of age (p = 0.204), gender (p = 0.180), ASA category (p = 0.346) as well as main preoperative tumor characteristics, liver function parameters, operative variables, and postoperative complications (p = 0.851). The perioperative morbidity (Clavien-Dindo ≥ 3a) and mortality were 21.7% (5/23) and 8.7% (2/23) in rHCC, while 25.4% (48/189) and 5.8% (11/189) in primary HCC, respectively (p = 0.851). The median overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) in the resection group were 40 months and 26 months, while median OS and RFS were 41 months and 29 months in the re-resection group, respectively (p = 0.933; p = 0.607; log rank).

Conclusion

Re-resection is technically feasible and safe in patients with rHCC. Further, comparative analysis displayed similar oncological outcome in patients with primary and rHCC treated by liver resection. Re-resection should therefore be considered in European patients diagnosed with rHCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a significant health-burden worldwide and the third most common cause of cancer-related mortality from a global perspective [1, 2]. Liver resection (LR) is the gold-standard treatment for patients with early HCC and nowadays even considered in individuals with advanced tumor stages [3,4,5]. Especially in patients with limited disease and preserved liver function, 10-year survival rates above 50% have been reported in selected cohorts [6]. However, as HCC arises on the background of chronic liver disease, tumor recurrence in the remnant liver, even after R0 resection, is reported in up to 80% of patients [7]. Salvage liver transplantation (SLT) might be an appropriate option for patients with recurrent HCC (rHCC) since it addresses both, the underlying liver damage and the oncological disease [8]. Unfortunately, a significant proportion of HCC patients do not qualify for transplantation due to older age, advanced tumor stages as well as major comorbidities or presence of other contraindications such as active alcohol abuse [9]. Moreover, the scarcity of liver grafts from deceased donors results in strict allocation rules limiting the utilization of SLT in this setting [8].

LR as therapy of primary HCC is well established and supported by a number of international guidelines. In contrast, the role of LR in rHCC remains to be determined [7, 10]. Especially for western patients, the evidence on LR in rHCC is limited, since most of the larger monocentric series are from Asian centers [11,12,13,14]. The available results are heterogeneous regarding perioperative complications and long-term outcome with 5-year survival ranging from 20 to 50% [13,14,15]. In addition, recent advances in liver surgery including the use of dynamic liver function tests e.g. LiMAx (maximum liver function capacity) or indocyanine green (ICG) and the increasing implementation of minimal-invasive liver surgery has broadened the disease spectrum in which LR appears feasible [16,17,18,19,20,21].

The aim of this study was to investigate short- and long-term outcomes in patients undergoing LR for rHCC compared to individuals with primary HCC in a monocentric European cohort of HCC patients.

Material and methods

Patients

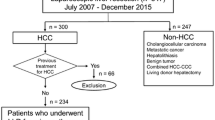

The study comprised two hundred-twelve (n = 212) consecutive HCC patients who underwent curative-intent surgery at the University Hospital RWTH Aachen (UH-RWTH) between 2010 and 2020. Clinical staging was performed according to international guidelines and all individuals had localized tumors without signs of systemic disease. The study was conducted at the UH-RWTH in accordance with the requirements of the Institutional Review Board of the RWTH-Aachen University (EK 503/21), the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the good clinical practice guidelines (ICH-GCP).

Staging and surgical technique

All patients who were referred for surgical treatment to our institution underwent a detailed clinical work-up as previously described [2, 22]. Therefore, the number, size, and location of tumor nodules as well as the presence of distant metastases were evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). The preoperative risk assessment was carried out based on the American society of anesthesiologists- (ASA) and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)-performance status, calculation of the future liver remnant (FLR) as well as parenchymal liver function as assessed by standard laboratory parameters and the LiMAx test (Humedics® GmbH, Berlin, Germany) [23]. Non-invasive liver function tests were routinely carried out, but no preoperative liver biopsies were obtained to assess the quality of the liver parenchyma. Patients staged Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) A to C without any evidence of extrahepatic spread as well as compensated liver function were considered as candidates for surgery as primary treatment. The definitive decision for hepatectomy was made by a staff hepatobiliary surgeon and approved by the institutional interdisciplinary tumor board for every patient. If transplantation was suggested for the individual patient, the case was referred to and discussed within the local transplantation board. Transplantation was generally preferred over re-resection if age, comorbidities or contraindications e.g., active alcoholism as well as advanced tumor stages were not precluding this approach. In transplant candidates fulfilling the Milan criteria and therefore undergo exceptional model of end stage liver disease (exMELD) allocation, transplantation was considered as the primary treatment [24]. In patients with rHCC not fulfilling the Milan criteria who presented with compensated liver function, surgery was preferred as the primary treatment. In patients not undergoing exMELD allocation with severe liver dysfunction, the suggested treatment was determined within a case-by-case decision approach evaluating the chance of organ allocation by regular MELD allocation and a perioperative risk assessment. Liver resection was carried out in accordance with common clinical standards [2, 22]. In brief, an intraoperative ultrasound was performed to visualize the local tumor spread and other suspicious lesions. The decision for either anatomic resections or non-anatomic atypical wedge resections with an adequate resection margin was based on the surgeon’s preference. Parenchymal transection was carried out using the Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator (CUSA®, Integra LifeSciences®, Plainsboro NJ, USA) with low central venous pressure (CVP) and intermittent Pringle maneuvers if necessary in open hepatectomy. In laparoscopic hepatectomy, parenchymal transection was commonly performed by Thunderbeat ® (Olympus K.K., Tokyo, Japan), Harmonic Ace ® (Ethicon Inc. Somerville, NJ, USA) or laparoscopic CUSA (Integra life sciences, New Jersey, USA) in combination with vascular staplers (Echelon, Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey, USA) or polymer clips (Teleflex Inc., Pennsylvania, USA). The anesthesiologic management was based on a restrictive fluid intervention strategy ensuring a low CVP during parenchymal dissection.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint of this study was the statistical comparison between patients undergoing resection versus re-resection for HCC in terms of perioperative complications and long-term oncological outcome. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the period from surgery to the date of death from any cause or the last contact if the patient was alive. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was measured from the date of resection to the date of first recurrence. RFS and OS in case of re-resection is defined from the time of re-resection until appearance of recurrence and the date of death from any cause or the last contact if the patient was alive, respectively. Patients who were free of tumor recurrence were censored at the time of death or at the last follow-up. Categorial data is presented in the form of numbers and percentages and compared using the chi-squared test, Fisher’s exact test or linear-by-linear association according to scale and number of cases. Data derived from continuous variables are presented as median and interquartile range and compared with the Mann–Whitney U-test. Survival curves were generated using Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Median follow-up was assessed with the reverse Kaplan–Meier method. Complications are reported as in-hospital morbidity and mortality. Perioperatively deceased patients were included in all survival analyses. The level of significance was set to p < 0.05 and p-values are given for two-sided testing. Analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Comparative analysis of the patient cohort

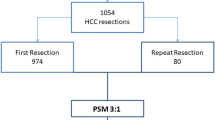

A total of 212 patients with a median age of 69 years who underwent curative-intent surgery for HCC at our institution from 2010 to 2020 were included in this study. Of these, a subgroup (n = 23) underwent re-resection due to rHCC and was compared to patients treated with surgery due to the primary HCC diagnosis (n = 189). More than half of the patients of both groups were male patients (resection group: 74.1% (140/189); re-resection group: 60.9% (14/23)) and assessed as ASA III or higher (resection group: 62.4% (118/189); re-resection group: 73.9% (17/23)). No differences between the groups regarding demographics and preoperative liver function despite a pronounced larger proportion of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in the primary resection cohort (41.3% (78/189) vs. 8.7% (2/23), p = 0.014) were observed. With respect to preoperative imaging, a tendency for a lower median nodule count (1 vs. 2, p = 0.101) and significantly larger tumors (53 mm vs. 36 mm, p = 0.007) in the primary resection group was detected. No other examined imaging features e.g. macrovascular invasion (p = 0.372) were different between the groups. Of note, laparoscopic resections were much more common in the primary resection group (34.4% (65/189) vs. 4.3% (1/23), p = 0.003) whereas other operative features including intraoperative and postoperative transfusion characteristics displayed no significant difference. Perioperative complications were observed in more than half of the individuals of each group (resection group: 51.3% (97/189); re-resection group: 56.5% (13/23)) but showed a balanced distribution in the group-comparison analysis (p = 0.851). However, a lower rate of post hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) according to the 50–50 criteria was observed in the resection group (1.1% (2/189) vs. 17.4% (4/23)) [21]. With respect to the pathological data, no difference in T category, microvascular invasion and tumor grading was found between the groups, but a tendency toward more R0 resections in the primary resection cohort (95.7% (180/189) vs. 87.0% (20/23) was displayed. The median time from initial treatment to re-resection in the rHCC cohort was 29 months (95% confidence interval (CI): 23–35 months). More clinicopathological and perioperative characteristics of both groups are outlined in Table 1 and a detailed overview about each case of the re-resection group is shown in Table 2.

Survival analysis

After a median follow-up of 50 months, the median OS of the cohort was 41 months (95%CI: 33–49 months; 3-year-OS = 58%, 5-year-OS = 41%) and the median RFS was 26 months (95%CI: 18–34 months; 3-year-RFS = 42%, 5-year-RFS = 33%; Fig. 1). Regarding the comparative analysis between the primary resection and re-resection groups, the median OS was 40 (95%CI: 31–49 months; 3-year-OS = 57%, 5-year-OS = 40%) in the resection cohort, while a median OS of 41 months (95%CI: 31–49 months; 3-year-OS = 66%, 5-year-OS = 44%) was observed in patients undergoing re-resection (p = 0.612 log rank; Fig. 2A). Also, no difference in RFS was detected between individuals undergoing primary resection (median RFS: 26 months (95%CI: 17–35 months), 3-year-RFS = 40%, 5-year-RFS = 33%) and patients treated by re-resection (median RFS: 29 months (95%CI: 2–56 months), 3-year-RFS = 52%,5-year-RFS = 35%; p = 0.675 log rank).

Oncological survival in hepatocellular carcinoma of the study cohort. A: Overall survival. The median OS of the cohort was 41 months (95%CI: 33–49 months). B: Recurrence-free survival. The median RFS of the cohort was 26 months (95%CI: 17–34 months). OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival

Oncological survival in hepatocellular carcinoma stratified by resection and re-resection. A: Overall survival. Patients undergoing primary resection showed a median OS of 40 months compared to 41 months in patients undergoing re-resection (p = 0.836 log rank). B: Recurrence-free survival. Patients undergoing primary resection showed a median RFS of 26 months compared to 29 months in patients undergoing re-resection (p = 0.946 log rank). OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival

Discussion

HCC represents one of the major global health issues with liver resection being the treatment of choice in patients with preserved liver function [1, 2, 8]. While the role of surgery in primary HCC is undoubtful supported with strong evidence, the ideal approach to rHCC is still under investigation and data focusing on Western patients are especially scarce [7, 10,11,12,13,14]. In a large cohort of European patients, we were able to demonstrate a notable short- and long-term outcome in patients with rHCC. Particularly, our data suggests that the oncological survival after LR for rHCC is similar to the survival after LR for primary HCC. Hence, LR should be considered as treatment option in European patients diagnosed with rHCC.

Suggested treatment modalities for rHCC range from re-resection and SLT over locoregional/interventional options or systematic therapies to best supportive care. The decision in favor of a certain therapy is based on the recurrence patterns, liver function, and overall physical performance status of the individual patient. Most experience regarding safety and oncological benefit of re-resection comes from Asian cohorts. In 1986, Nagasue et al. first reported a small series of 9 patients who underwent resection of rHCC [25]. Since then, multiple case-series from Eastern Asia have been published with the largest mono-centric cohort reported by Zou et al. comprising more than 600 patients [14]. In this study, the median OS after re-resection was 27 months which is notably shorter than in our admittedly smaller cohort of patients reported here (median OS 41 months). This is particularly interesting since multifocal disease (52.1% vs. 15.1%) as well as the tumors > 3 cm (60.9% vs. 13.0%) were more frequent in our cohort. However, microvascular invasion (30.4% vs. 55.7%) was less often detected which might at least in part explain the observed differences (Tables 1 and 2 [14]). The largest series on Western patients has been published by Roayaie et al. in 2010 and included 35 patients from Italy and the USA [26]. Interestingly, only patients with a single recurrent tumor on imaging and Child A liver disease were included which translates into an excellent median OS of 59 months (5-year-OS = 67%) in this study. More in line with our results is the report by Fabel et al. showing a median OS of 36 months (5-year-OS = 42%) in 31 patients treated by re-resection for rHCC [27]. While the survival data appears comparable between our study and the publication from Faber et al., our cohort displayed significantly higher morbidity (56.5% vs. 11.1%) and mortality (8.7% vs. 0%). However, it must be noted that our department policies also comprise surgery for patients staged BCLC A to C in both primary and recurrent HCC. Thus, our re-resection cohort also included complex cases treated by major liver resection and additional procedures such as portal vein resections (PVR) or the concomitant resection of adjacent organs (e.g. the pancreatic head (Table 2)).

While most of the available literature solely reports outcome in patients with rHCC, we additionally compared to short- and long-term outcome of patients undergoing LR for primary HCC. We noticed no statistical differences in a variety of pre-, intra- and postoperative characteristics except for larger proportion of NAFLD patients, more individuals undergoing laparoscopic resection and slightly larger tumors in patients with primary HCC resection. In contrast, posthepatectomy liver failure was more common in the rHCC cohort. Further, a statistically not significantly increased nodule count was observed in the re-resection cohort (Table 1). Overall, known oncological risk factors especially microvascular invasion and pathological staging were balanced between the resection and re-resection cohort, therefore allowing a meaningful comparative analysis regarding oncological outcome without further matching [28]. Particularly, we detected no difference in OS and RFS between patients undergoing resection or re-resection for HCC. This suggests that rHCC is per se not a prognostic factor for poor oncological outcome and indicates that these patients should not be treated differently from patients with the first diagnosis of HCC. As LR is universally recommended as a first-line treatment for primary HCC across common guidelines and expert opinions, re-resection should therefore also be considered in patients presenting with rHCC [7, 10].

Interestingly, in our study the rate of laparoscopic LR was notably higher in the resection than in the re-resection group. As laparoscopic LR was routinely implemented during the later study period, most patients undergoing re-resection were treated by open hepatectomy in the initial procedure. This and the complexity of the cases with rHCC as described above certainly explain the low rate of laparoscopic LR in the rHCC group. Even today, laparoscopic re-resection remains challenging in case of rHCC due to the formation of intraabdominal adhesions. Currently, only a few studies are available focusing on laparoscopic re-resection in rHCC [29,30,31,32]. However, a recent meta-analysis based on Eastern patients showed that laparoscopic re-resection for rHCC is associated with fewer overall complication and a shorter hospitalization but displayed similar 90-day mortality compared to conventional re-resection [33].

While large studies from Asia regarding the role of re-resection for rHCC already exist, it is yet to be explored whether these results are unconditionally transferable to Western patients [9]. The general approach to HCC seems to be more aggressive in Asian countries. This might partially be explained by the larger proportion of viral etiology in Eastern patients which results in a generally younger HCC population with often less severe underlying cirrhosis and fewer comorbidities [34]. Therefore, adjusted staging system, e.g. Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging (HKLC), Japanese Integrated System (JIS) or Chinese University Integrated System (CUPI), are used to guide treatment in Asian patients but are less useful in Western populations [35, 36]. Even genomic characteristics vary between Asian and European patients [37]. Thus, treatment recommendation for HCC in European patients, especially in the complex situation of rHCC, should preferably be based on data from European cohorts.

Our long-term oncological results are at the price of significant morbidity and mortality. This gives rise to the question of alternative treatment modalities. SLT is often proposed as it resolves the issue of underlying liver disease and treats potential micrometastases. However, the procedure itself is also associated with a relatively high morbidity [38]. Notably, a recent meta-analysis comparing SLT to other treatment modalities confirmed the advantage of SLT in long-term outcomes [39]. In addition, the direct comparison of re-resection with SLT within a subgroup analysis showed preferable 3- and 5-year-RFS for the SLT cohort [39]. Nonetheless, especially in Germany with one of the lowest number of available deceased donor allografts among Western countries, the use of SLT is strongly limited by the shortage of available donor grafts. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is also suggested to be a valid alternative for re-resection. In particular, RFA is nowadays considered to be equivalent to LR in small solitary HCC and, therefore, recommended by various guidelines [7, 10, 40]. However, data basis for rHCC is yet to be fully unraveled. In a recent monocentric report from Singapore, re-resection was associated with a late survival benefit but displayed a higher procedural morbidity rate [41]. In contrast, combined data from China and Italy displayed longer RFS upon re-resection but failed to convey an improved OS compared to RFA [42]. Similar to the report by Chua et al., morbidity was also higher after re-resection in this study [41]. While therapeutic alternatives for re-resection are certainly clinically appealing, our analysis cannot enlighten this issue, and further investigations in a randomized setting are required to determine the ideal approach to rHCC.

Whether time to recurrence from primary resection should guide treatment decisions is currently debated within the international literature [28, 43]. Our rHCC cohort comprised patients with disease recurrence after less than 1 year up to patients with a DFS of more than 5 years underlining our surgical approach in every feasible recurrence situation. To further investigate this issue of early versus late recurrence, we pragmatically split our rHCC subgroup into two almost equal sized groups (cut-off 26 months) and observed a tendency for longer OS and DFS in patients experiencing later recurrence (supplementary Figure S1, supplementary Table S1). While our dataset does not allow to elaborate further statistically associations here, this observation is in line with previous reports investigating the late versus early recurrence topic [28, 43]. Of note, in a recent publication of Wei et al., individuals undergoing curative treatment approach for late recurrence displayed comparable OS with patients without disease relapse and patients with early recurrence showed inferior OS after curative re-treatment compared to patients with no recurrence, yet still a better outcome than patients undergoing palliative treatment for early recurrence which underlines the role of surgery in both scenarios [43].

Like any other observational clinical study, our analysis has certain inherent limitations. All HCC patients analyzed in this study underwent treatment in a monocentric setting reflecting our individual clinical approach to this disease and the study is based on a retrospective data collection which was not obtained in the setting of a controlled clinical trial. This also results in large proportion of ASA III patients and individuals with higher BCLC stages due to our aggressive treatment approach. Moreover, our data set appears small compared to some other studies especially from Asian cohorts. Further, our relatively small data set did not allow to conduct a meaningful sub-analysis investigating clinical and oncological differences between early and late disease recurrences.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the aforementioned limitations, we show that re-resection is technically feasible and safe in patients with rHCC. Further, comparative analysis displayed similar oncological outcome in patients with primary and rHCC treated by liver resection. Re-resection should therefore be considered in European patients diagnosed with rHCC.

Abbreviations

- ALD:

-

Alcoholic liver disease

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- ALPPS:

-

Associating liver partition with portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy

- AP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- ASA:

-

American society of anesthesiologists

- AST :

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BCLC:

-

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CPS:

-

Child Pugh Score

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CUPI:

-

Chinese University Integrated System

- CUSA:

-

Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator

- CVP:

-

Central venous pressure

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- FFP:

-

Fresh frozen plasma

- FLR:

-

Future liver remnant

- GCP:

-

Good clinical practice

- GGT:

-

Gamma glutamyltransferase

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HJ:

-

Hepaticojejunostomy

- HKLC:

-

Hong Kong Liver Cancer

- ICG:

-

Indocyanine green

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- ISGLS :

-

International Study Group of Liver Surgery

- JIS :

-

Japanese Integrated System

- LiMAX:

-

Maximum liver function capacity

- LR:

-

Liver resection

- MELD:

-

Model of end-stage liver disease

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NAFLD:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PHLF :

-

Posthepatectomy liver failure

- PVE:

-

Portal vein embolization

- PVR:

-

Portal vein resection

- RFA:

-

Radiofrequency ablation

- RFS:

-

Recurrence-free survival

- rHCC:

-

Recurrent HCC

- SLT:

-

Salvage liver transplantation

- TACE:

-

Transarterial chemoembolization

- TARE:

-

Transarterial radioembolization

- TSH:

-

Two-stage hepatectomy

- UH-RWTH:

-

University Hospital Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule

- UICC:

-

Union for international cancer control

References

Siegel R, Naishadham D (2012) Jemal A (2012) Cancer statistics for Hispanics/Latinos. CA: Cancer J Clin 62(5):283–298. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21153

Lurje G, Bednarsch J, Czigany Z, Amygdalos I, Meister F, Schoning W, Ulmer TF, Foerster M, Dejong C, Neumann UP (2018) Prognostic factors of disease-free and overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing partial hepatectomy in curative intent. Langenbeck’s archives of surgery/Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie 403(7):851–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-018-1715-9

Bruix J, Reig M, Sherman M (2016) Evidence-based diagnosis, staging, and treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 150(4):835–853. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.041

Vitale A, Burra P, Frigo AC, Trevisani F, Farinati F, Spolverato G, Volk M, Giannini EG, Ciccarese F, Piscaglia F, Rapaccini GL, Di Marco M, Caturelli E, Zoli M, Borzio F, Cabibbo G, Felder M, Gasbarrini A, Sacco R, Foschi FG, Missale G, Morisco F, Svegliati Baroni G, Virdone R, Cillo U, Cancer IL, g, (2015) Survival benefit of liver resection for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma across different Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages: a multicentre study. J Hepatol 62(3):617–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.037

Roayaie S, Jibara G, Tabrizian P, Park JW, Yang J, Yan L, Schwartz M, Han G, Izzo F, Chen M, Blanc JF, Johnson P, Kudo M, Roberts LR, Sherman M (2015) The role of hepatic resection in the treatment of hepatocellular cancer. Hepatology 62(2):440–451. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27745

Li YC, Chen PH, Yeh JH, Hsiao P, Lo GH, Tan T, Cheng PN, Lin HY, Chen YS, Hsieh KC, Hsieh PM, Lin CW (2021) Clinical outcomes of surgical resection versus radiofrequency ablation in very-early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 21(1):418. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-01995-z

Kokudo N, Takemura N, Hasegawa K, Takayama T, Kubo S, Shimada M, Nagano H, Hatano E, Izumi N, Kaneko S, Kudo M, Iijima H, Genda T, Tateishi R, Torimura T, Igaki H, Kobayashi S, Sakurai H, Murakami T, Watadani T, Matsuyama Y (2019) Clinical practice guidelines for hepatocellular carcinoma: The Japan Society of Hepatology 2017 (4th JSH-HCC guidelines) 2019 update. Hepatology research: the official journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology 49(10):1109–1113. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.13411

Rahbari NN, Mehrabi A, Mollberg NM, Muller SA, Koch M, Buchler MW, Weitz J (2011) Hepatocellular carcinoma: current management and perspectives for the future. Ann Surg 253(3):453–469. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820d944f

Bednarsch J, Czigany Z, Heise D, Joechle K, Luedde T, Heij L, Bruners P, Ulmer TF, Neumann UP, Lang SA (2021) Prognostic evaluation of HCC patients undergoing surgical resection: an analysis of 8 different staging systems. Langenbeck’s archives of surgery / Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie 406(1):75–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-020-02052-1

European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address eee, European Association for the Study of the L (2018) EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 69(1):182–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019

Kobayashi A, Kawasaki S, Miyagawa S, Miwa S, Noike T, Takagi S, Iijima S, Miyagawa Y (2006) Results of 404 hepatic resections including 80 repeat hepatectomies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 53(71):736–741

Itamoto T, Nakahara H, Amano H, Kohashi T, Ohdan H, Tashiro H, Asahara T (2007) Repeat hepatectomy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery 141(5):589–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2006.12.014

Huang ZY, Liang BY, Xiong M, Zhan DQ, Wei S, Wang GP, Chen YF, Chen XP (2012) Long-term outcomes of repeat hepatic resection in patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma and analysis of recurrent types and their prognosis: a single-center experience in China. Ann Surg Oncol 19(8):2515–2525. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2269-7

Zou Q, Li J, Wu D, Yan Z, Wan X, Wang K, Shi L, Lau WY, Wu M, Shen F (2016) Nomograms for pre-operative and post-operative prediction of long-term survival of patients who underwent repeat hepatectomy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 23(8):2618–2626. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5136-0

Minagawa M, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Kokudo N (2003) Selection criteria for repeat hepatectomy in patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 238(5):703–710. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000094549.11754.e6

Stockmann M, Lock JF, Riecke B, Heyne K, Martus P, Fricke M, Lehmann S, Niehues SM, Schwabe M, Lemke AJ, Neuhaus P (2009) Prediction of postoperative outcome after hepatectomy with a new bedside test for maximal liver function capacity. Ann Surg 250(1):119–125. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ad85b5

Lurje I, Czigany Z, Bednarsch J, Roderburg C, Isfort P, Neumann UP, Lurje G (2019) Treatment strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma (-) a multidisciplinary approach. Int J Mol Sci 20 (6). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20061465

Imamura H, Seyama Y, Kokudo N, Maema A, Sugawara Y, Sano K, Takayama T, Makuuchi M (2003) One thousand fifty-six hepatectomies without mortality in 8 years. Archives of surgery 138(11):1198–1206. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.138.11.1198 (discussion 1206)

Ciria R, Cherqui D, Geller DA, Briceno J, Wakabayashi G (2016) Comparative short-term benefits of laparoscopic liver resection: 9000 cases and climbing. Ann Surg 263(4):761–777. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001413

Takahara T, Wakabayashi G, Beppu T, Aihara A, Hasegawa K, Gotohda N, Hatano E, Tanahashi Y, Mizuguchi T, Kamiyama T, Ikeda T, Tanaka S, Taniai N, Baba H, Tanabe M, Kokudo N, Konishi M, Uemoto S, Sugioka A, Hirata K, Taketomi A, Maehara Y, Kubo S, Uchida E, Miyata H, Nakamura M, Kaneko H, Yamaue H, Miyazaki M, Takada T (2015) Long-term and perioperative outcomes of laparoscopic versus open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with propensity score matching: a multi-institutional Japanese study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 22(10):721–727. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.276

Balzan S, Belghiti J, Farges O, Ogata S, Sauvanet A, Delefosse D, Durand F (2005) The “50–50 criteria” on postoperative day 5: an accurate predictor of liver failure and death after hepatectomy. Annals of surgery 242(6):824–828 (discussion 828–829)

Bednarsch J, Czigany Z, Lurje I, Trautwein C, Ludde T, Strnad P, Gaisa NT, Barabasch A, Bruners P, Ulmer T, Lang SA, Neumann UP, Lurje G (2020) Intraoperative transfusion of fresh frozen plasma predicts morbidity following partial liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04652-0

Buechter M, Thimm J, Baba HA, Bertram S, Willuweit K, Gerken G, Kahraman A (2019) Liver maximum capacity: a novel test to accurately diagnose different stages of liver fibrosis. Digestion 100(1):45–54. https://doi.org/10.1159/000493573

Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L (1996) Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 334(11):693–699. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199603143341104

Nagasue N, Yukaya H, Ogawa Y, Sasaki Y, Chang YC, Niimi K (1986) Second hepatic resection for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 73(6):434–438. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800730606

Roayaie S, Bassi D, Tarchi P, Labow D, Schwartz M (2011) Second hepatic resection for recurrent hepatocellular cancer: a Western experience. J Hepatol 55(2):346–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.026

Faber W, Seehofer D, Neuhaus P, Stockmann M, Denecke T, Kalmuk S, Warnick P, Bahra M (2011) Repeated liver resection for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 26(7):1189–1194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06721.x

Xing H, Zhang WG, Cescon M, Liang L, Li C, Wang MD, Wu H, Lau WY, Zhou YH, Gu WM, Wang H, Chen TH, Zeng YY, Schwartz M, Pawlik TM, Serenari M, Shen F, Wu MC, Yang T (2020) Defining and predicting early recurrence after liver resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-institutional study. HPB: The official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association 22(5):677–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2019.09.006

Goh BKP, Syn N, Teo JY, Guo YX, Lee SY, Cheow PC, Chow PKH, Ooi L, Chung AYF, Chan CY (2019) Perioperative outcomes of laparoscopic repeat liver resection for recurrent HCC: comparison with open repeat liver resection for recurrent HCC and laparoscopic resection for primary HCC. World J Surg 43(3):878–885. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4828-y

Goh BK, Teo JY, Chan CY, Lee SY, Cheow PC, Chung AY (2016) Review of 103 cases of laparoscopic repeat liver resection for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 26(11):876–881. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2016.0281

Liu K, Chen Y, Wu X, Huang Z, Lin Z, Jiang J, Tan W, Zhang L (2017) Laparoscopic liver re-resection is feasible for patients with posthepatectomy hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence: a propensity score matching study. Surg Endosc 31(11):4790–4798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5556-3

Chan AC, Poon RT, Chok KS, Cheung TT, Chan SC, Lo CM (2014) Feasibility of laparoscopic re-resection for patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg 38(5):1141–1146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2380-3

Cai W, Liu Z, Xiao Y, Zhang W, Tang D, Cheng B, Li Q (2019) Comparison of clinical outcomes of laparoscopic versus open surgery for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 33(11):3550–3557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-06996-4

Vibert E, Ishizawa T (2012) Hepatocellular carcinoma: Western and Eastern surgeons’ points of view. J Visc Surg 149(5):e302-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2012.05.001

Yau T, Tang VY, Yao TJ, Fan ST, Lo CM, Poon RT (2014) Development of Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system with treatment stratification for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 146 (7):1691–1700 e1693. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.032

Nanashima A, Sumida Y, Morino S, Yamaguchi H, Tanaka K, Shibasaki S, Ide N, Sawai T, Yasutake T, Nakagoe T, Nagayasu T (2004) The Japanese integrated staging score using liver damage grade for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients after hepatectomy. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology 30(7):765–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2004.05.003

Choo SP, Tan WL, Goh BKP, Tai WM, Zhu AX (2016) Comparison of hepatocellular carcinoma in Eastern versus Western populations. Cancer 122(22):3430–3446. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30237

Pasini F, Seranari M, Cucchetti A, Ercolani G (2020) Treatment options for recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection: review of the literature and current recommendations for management. Hepatoma Res 6 (26). https://doi.org/10.20517/2394-5079.2019.47

Wang HL, Mo DC, Zhong JH, Ma L, Wu FX, Xiang BD, Li LQ (2019) Systematic review of treatment strategy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: salvage liver transplantation or curative locoregional therapy. Medicine 98(8):e14498. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000014498

Chen MS, Li JQ, Zheng Y, Guo RP, Liang HH, Zhang YQ, Lin XJ, Lau WY (2006) A prospective randomized trial comparing percutaneous local ablative therapy and partial hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 243(3):321–328. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000201480.65519.b8

Chua DW, Koh YX, Syn NL, Chuan TY, Yao TJ, Lee SY, Goh BKP, Cheow PC, Chung AY, Chan CY (2021) Repeat hepatectomy versus radiofrequency ablation in management of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: an average treatment effect analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 28(12):7731–7740. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-09948-2

Zhong JH, Xing BC, Zhang WG, Chan AW, Chong CCN, Serenari M, Peng N, Huang T, Lu SD, Liang ZY, Huo RR, Wang YY, Cescon M, Liu TQ, Li L, Wu FX, Ma L, Ravaioli M, Neri J, Cucchetti A, Johnson PJ, Li LQ, Xiang BD (2021) Repeat hepatic resection versus radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: retrospective multicentre study. Br J Surg 109(1):71–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znab340

Wei T, Zhang XF, Bagante F, Ratti F, Marques HP, Silva S, Soubrane O, Lam V, Poultsides GA, Popescu I, Grigorie R, Alexandrescu S, Martel G, Workneh A, Guglielmi A, Hugh T, Lv Y, Aldrighetti L, Pawlik TM (2021) Early versus late recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection based on post-recurrence survival: an International Multi-institutional Analysis. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 25(1):125–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04553-2

Rahbari NN, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Brooke-Smith M, Crawford M, Adam R, Koch M, Makuuchi M, Dematteo RP, Christophi C, Banting S, Usatoff V, Nagino M, Maddern G, Hugh TJ, Vauthey JN, Greig P, Rees M, Yokoyama Y, Fan ST, Nimura Y, Figueras J, Capussotti L, Buchler MW, Weitz J (2011) Posthepatectomy liver failure: a definition and grading by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS). Surgery 149(5):713–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2010.10.001

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to this manuscript and are in agreement with the content. The authors contributed as followed:

• Study conception and design: JB, UPN, SAL.

• Acquisition of data: JB, ZC, LRH, IA, DH, PB.

• Analysis and interpretation of data: JB, TFU, UPN, SAL.

• Drafting of manuscript: JB, UPN, SAL.

• Critical revision of manuscript: ZC, LRH, IA, DH, PB, TFU.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was conducted at the UH-RWTH in accordance with the requirements of the Institutional Review Board of the RWTH-Aachen University (EK EK 503/21). All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bednarsch, J., Czigany, Z., Heij, L.R. et al. The role of re-resection in recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg 407, 2381–2391 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-022-02545-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-022-02545-1