Abstract

Purpose

To present social media (SoMe) platforms for surgeons, how these are used, with what impact, and their roles for research communication.

Methods

A narrative review based on a literature search regarding social media use, of studies and findings pertaining to surgical disciplines, and the authors’ own experience.

Results

Several social networking platforms for surgeons are presented to the reader. The more frequently used, i.e., Twitter, is presented with details of opportunities, specific fora for communication, presenting tips for effective use, and also some caveats to use. Details of how the surgical community evolved through the use of the hashtag #SoMe4Surgery are presented. The impact on gender diversity in surgery through important hashtags (from #ILookLikeASurgeon to #MedBikini) is discussed. Practical tips on generating tweets and use of visual abstracts are presented, with influence on post-production distribution of journal articles through “tweetorials” and “tweetchats.” Findings from seminal studies on SoMe and the impact on traditional metrics (regular citations) and alternative metrics (Altmetrics, including tweets, retweets, news outlet mentions) are presented. Some concerns on misuse and SoMe caveats are discussed.

Conclusion

Over the last two decades, social media has had a huge impact on science dissemination, journal article discussions, and presentation of conference news. Immediate and real-time presentation of studies, articles, or presentations has flattened hierarchy for participation, debate, and engagement. Surgeons should learn how to use novel communication technology to advance the field and further professional and public interaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In less than two decades since its inception, social media has had a dramatic impact on science dissemination, journal article discussions, conference news, and sharing of ideas and findings [1,2,3,4]. Social media relates to all internet-based applications used for social interaction in real time, be it for personal or professional use. It has changed several aspects of how, what, when, and with whom we communicate—this holds true not only in personal life, but more so in professional aspects and academia [4,5,6].

Medicine is no exception and surgeons have taken to the social media platforms with varying but increasing activity [7,8,9]. This method of research communication requires both attention, curiosity, critique, and scientific research. With several new opportunities for research communication, knowledge dissemination, education, and debates in real time, social media platforms are important tools for surgeons. However, in addition to opportunities and advantages, there are concerns, caveats, and pitfalls to this technology as well.

In this invited review, we present some of the aspects related to social media use for surgeons and how it influences modern research communication.

How surgeons use social media platforms

Since the invention of the printing press, methods for staying up to date with the latest medical evidence have evolved alongside the practice of evidence-based medicine itself. The speed of this evolution increased exponentially when the first scientific journals began to make their papers available online. The BMJ was the first major medical journal to launch a website, in 1995, and went fully online in 1998 [10]. From the mid-1990s, journals started offering the option to sign up for e-mail updates and RSS feeds (a method that allows a user to receive aggregated updates in a standardized format from multiple news sources).

Next came the blogs [11] (a term coined in 1997) and podcasts from the 2000s (the name was first used in 2004) [12]. Medical versions of these media are still incredibly popular. They allow journal editors and individual doctors to discuss, critique, and share important studies. Podcasts can be listened to at leisure, such as during commutes and exercise. Creating and maintaining them can be time-consuming. Hence, their use by surgical journals for communication with readers has been relatively inconsistent.

When Facebook (Facebook Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) was created in 2004, personalized news feeds became more appealing than RSS feeds [13]. Articles could be shared easily by friends and colleagues. More social networks then rapidly developed, and surgeons adopted them for socializing, networking, research, and practice promotion. Among colorectal surgeons in Australia and New Zealand, 59% reported using social media (SoMe) for networking and 9% for research purposes [14]. A summary of these platform types are found in Table 1. Among the social media tools available, some are more popular among the surgical community than others. While only used by approximately one in five US adults [15], Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) has become popular among healthcare professionals worldwide, for sharing information and online content; users can use it for both broadcasting and interacting [16]. The adoption of social media by the surgical community has been gradual. Twitter seems to be one of the platforms with largest uptake by surgeons [3, 8, 17, 18].

Social networks

Facebook is one of the most used platforms; e.g., in the USA, it is used by over two-thirds of the adult population [15]. Despite this, it is infrequently used by individual surgeons for purely professional purposes, as it encourages users to share personal information such as family members and tagged pictures of private events that are not always appropriate for professional interactions. However, as it allows a “closed” membership, it is used by some societies to facilitate discussions and engagement [19]. This approach leverages members’ existing social media accounts and familiarity with the platform to engage them in case discussion and webinars, thereby broadening participation compared to society-specific web platform that requires separate processes and login. It can also add a socializing and networking aspect to discussions that was previously achieved mostly at in-person conferences. Instagram (Facebook Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) is owned by Facebook and is used by a younger demographic. Due to it being primarily an image-sharing platform, it is popular within plastic and aesthetic surgery [20, 21]. It is also used by private medical institutions to advertise medical activity and facilities [17].

Blogs

Surgical blogs have experienced a recent renaissance [22, 23]. Blogging is a good vehicle for topics not covered in traditional scientific literature and that require a more extensive coverage than the short format proposed on the other platforms. Surgical blogs may be targeted to a specific audience, such as the Association of Women Surgeons (AWS) blog [23]. This example generates high numbers of unique user views and provides unique content, such as topics including “graduate and postgraduate education” and “family life,” among others. Blogs can also be used by scientific journals. BJS created a blog that allows the journal’s editors and authors to post articles on themes that are not traditionally found in a printed journal (The Cutting Edge blog https://cuttingedgeblog.com). These posts stimulate debate and allow reflection in an alternative way. In addition, they allow the communication of the findings of surgical research in plain language, to make it available to the general public. This is an important method of countering widespread medical misinformation online. Surgical blogs can thus be used for knowledge dissemination and translation, as well as patient engagement in research. Research outputs can be shared with the surgical community, policy-makers, and patients in formats more accessible than scientific articles. Clinical trials and ongoing studies can be shared to improve centers’ participation and patient recruitment [24]. Interactive features can also be used to obtain input and feedback through the design, conduct, and interpretation of research projects to foster patient and service user engagement that is key to impactful research [25].

Video sharing

YouTube (Google LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA) is the most popular form of social media in the USA, with three-quarters of adults using the platform [15]. It is particularly useful for sharing educational videos, recorded lectures, webinars, and instructional procedure videos. Research suggests there is broad uptake of these videos [26, 27]. Several surgical specialties have used this form of knowledge distribution for various procedures [28,29,30,31]; however a recurring concern is the validity and usefulness of the content posted [32,33,34]. There is no surgical content curator on YouTube. Hence, the inexperienced surgeon may be led astray into poorly crafted and potentially erroneous videos, which is a pitfall to the widespread dissemination available by these platforms. Compared with traditional journal articles in a professional surgical journal, social platform content is not vetted to a given standard with editorial input or external referees. Thus, bias (unconscious and conscious) and errors are rife. In a cross-sectional study of YouTube videos demonstrating laparoscopic fundoplication, only 39.4% were evaluated as “good”; good-rated videos correlated with longer duration [35]. Similarly, an analysis of YouTube videos presenting D2 lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer highlighted the high variability in the quality of the technique presented using validated scoring tools [36]. Higher quality videos have supplementary commentary [26]. Trainees may also evaluate the quality of a surgical video differently to senior surgeons [34] and should therefore be steered towards the higher quality videos by their instructors.

Formal curation is provided by other video platforms, such as WebSurg and the AIS (Advances in Surgery) Channel. As with other online streaming platforms, these tools gained more visibility during the Covid-19 pandemic, when in-person congresses were cancelled and partly replaced with virtual events [37]. It is unclear what the role of these formats will be once in-person conferences resume, but their persistence seems certain.

How it started: #SoMe4Surgery and related hashtags

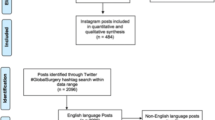

One of the ways to maximize the benefits of social media use is to employ hashtags, which are metadata tags that are user-generated/“bottom-up” [38]. This allows users to engage in conversations that are related to a certain topic. Various surgical hashtags exist. #SoMe4Surgery is both one of the most widespread and most surgeon-specific on Twitter [39] (Fig. 1). The hashtag was developed through several phases and described in detail elsewhere [39]. Briefly, an inception phase was initiated for a connection between participants: users were actively invited to participate. Second, a dissemination phase was launched to help the spread (contagion) and the material going viral. In this phase, several tweetchats were designed, scheduled, and run. Further, a third step was the adherence phase (feedback): Twitonomy and NodeXL summaries were regularly posted on Twitter to gauge and inform activity and response. Eventually, an impact phase in which outcome was the focused gain [1, 39]. Created in August 2018, after 2 years and 4 months, the #SoMe4Surgery network and the twitter handle (@me4_so) had reached over 5000 followers, with considerable interaction (Fig. 1). Currently, a long list of twitter handles related to surgeons’ interest is available (Table 2).

Social media and social change

It is possible for content to be shared online in such a way that it spreads extremely rapidly, i.e., “going viral.” Examples of hashtags that went viral in the “Twittersphere” (Twitter ecosystem) and have had a huge social influence on surgery include #ILookLikeASurgeon, the #NYerORCoverChallenge (Fig. 2), and #HerTimeIsNow. These hashtags have celebrated diversity, raised awareness of discrimination and microaggression, and promoted the recognition of women surgeons [3]. Indeed, social media has addressed sexism in science in a wider perspective [40], stirring debate and encouraging progress towards gender equity and opportunities. As such, #ILookLikeASurgeon has become a global phenomenon [41] with several specialties taking up the challenge [42].

Social media and social change in gender diversity in surgery. After publication of the cover on the magazine, The New Yorker (A), the Twitter platform was used as a vehicle to promote women surgeons (B) working in institutions across the world, reproducing the cover art and thus giving a face to the thousands of women surgeons in current surgical practice. (C) The HeForShe Twitter handle mobilizing for gender equity. (D) The initial tweet by Heather Logghe starting the #ILookLikeASurgeon hashtag that eventually went viral

Social media allows for wider inclusion. It is now easier for junior surgeons or underrepresented groups to create a voice for themselves and make their expertise and contributions known. This helps to make them more accessible for opportunities such as invitations for speaking engagements, whereas without social media, this would be contingent on contacts and networking at meetings, which is not possible nor intuitive for all. SoMe also allows more opportunities to amplify others, support, and promote one another. This has certainly been the case for women within the American Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Association (AHPBA) with the hashtag #hpbheroines. While not all hashtags may go “viral,” they may become impactful, even powerful, tools in certain communities. Indeed, speaker representation of women in the IHPBA conference held in Brisbane 2020 was altered after the Twitter community noted the lack of women invited speakers. Hence, social media may bring a “diversity bonus” by fostering teams that would not have existed otherwise—be it for conferences, webinars, or research collaborations.

However, there are still limitations. Social media does not entirely protect for disparities, and geographical disparities in particular have already been identified in the use of social platforms. Independently of their utility, some platforms are preferred by users based on their local popularity [15, 43, 44]. Although access to the global conversation in surgery on Twitter is free of charge, and experts are present and active, some countries still remain underrepresented, as it has already been shown at a more global level [45]. Potential reasons for geographical disparities range from poverty and lack of resources, preventing access to the internet, to political (in countries with restricted freedom of speech), linguistical, and cultural.

Social media engagement in research—from idea to project

It is possible for a research paper to be entirely conceived, constructed, contributed to, and disseminated via social media. The phenomenal advantage of this concept is the ability to collaborate with esteemed international colleagues with which it would otherwise be impossible to network. In addition, social media acts to “flatten the hierarchy,” allowing junior researchers to approach legends of their specialties with their own ideas, in return stimulating their own interest in research (Table 3).

Post-production

Following publication, there are numerous methods of disseminating research to maximize impact. Some advice for promoting papers on Twitter are found in Table 4.

Tweetorials

Tweetorials, or tweet tutorials, are explanatory Twitter threads posted on an academic topic [60] (see example Fig. 3). They are often posted by the authors of papers to explain their findings in plain language and employ the use of images from the paper as well as animated GIFs to illustrate the topic. Because the paper is explained in short, 280-character snippets, they are effective tools to summarize the key points of a paper. The caveat is that if threads are too long, the audience may not read to the end (a reflection of the short attention span encouraged by the use of microblogging sites).

Example of a tweetorial. After the 2019 Nordic HPB meeting in Helsinki, Finland, a tweetorial was presented by the host Ville Sallinen of a summary presentation. The full tweetorial can be read at https://twitter.com/villesallinen/status/1210119626165755905. The use of social media allows non-participants to take part and engage in content, allowing for a wider distribution and input to a meeting

Tweetchats

A tweetchat is an open conversation on Twitter, usually based around the use of a hashtag, and often guided by one or two accounts that may post a series of questions designed to stimulate discussion [16]. They are employed by medical journals, researchers, and journal clubs to promote published papers and are highly effective in increasing the alternative metrics (Altmetrics) and reach of the paper, with impressions (number of times the hashtag has been viewed) sometimes in the millions. In one study [16], individual tweets from a journal tweetchat were extracted using Twitter analytics in addition to third-party applications NodeXL and Twitonomy, which showed that 37 Twitter accounts posted 248 tweets or replies, with only 58.5% identified using the hashtag of the tweetchat. It is therefore possible for the conversation to quickly become disorganized and difficult to follow, particularly if participants forget to include the hashtag. Third-party applications may also overestimate the reach of hashtags.

Condensed communication—from 280 characters to visual abstracts

The traditional form of condensed presentation is through the scientific abstract—either as a meeting abstract or as a condensed part of a journal article (Fig. 4). The structured part of an article usually consists of about 250 words following the IMRaD (introduction, methods, results, and discussion) structure [61].

Traditional and alternative metrics for measuring research output. The metrics used to evaluate the impact of social media activity are changing; in a, the traditional focus on citations and impact factor (IF; Journal Citation Reports ©Clarivate Analytics) is increasingly challenged by b alternative metrics, dubbed “altmetrics” for short (collected by various projects, including Altmetric, Plum Analytics, and ImpactStory), that collect views and mentions over a wide range of sources, including (but not limited to) peer reviews on faculty of 1000, citations on Wikipedia and in public policy documents, discussions on research blogs, mainstream media coverage, bookmarks on reference managers like Mendeley, and social networks such as Twitter. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier under the Creative Commons license from Søreide [3]

The “visual abstract” has not replaced but added visual value to the traditional scientific abstract [62,63,64]. Most surgical journals now post visual abstracts of many of their published studies (Fig. 5). Indeed, some journals, like the Journal of American College of Surgeons (JACS) and JAMA Surgery, require authors to provide a visual abstract of their work at the time of article submission or revision. Suggested information to include in a visual abstract are found in Table 5 [65].

The visual abstract. An example of a visual abstract used to post summary content of a study published in BJS (courtesy of R. G.). The tweet with the visual abstract also contains a few notes on the study and should also contain a link or shortcut to the paper itself, hence acting as a teaser to attract the reader to study the full-text version. Thus, the purpose of the visual abstract is to be simplistic in message, yet will not replace the need to read and understand the full depth of the paper

Specialized feeds for disseminating research

Social media platforms such as Twitter are immensely useful for keeping up to date with the latest research. However, feeds can often be cluttered by a mixture of useful links to journals, distracting viral videos, and photographs of pets. A relatively new trend is of Twitter accounts that act to filter out the noise (Table 6). These are usually run by volunteers with a passion for academic medicine, who act to curate and filter the papers by specialty, as opposed to the personal accounts of doctors and scientists, who may post mainly their own work. Some are run by bots. Following the creation of the #SoMe4Surgery hashtag and @me4_so (SoMe4Surgery) Twitter account [39], numerous subspecialty surgical accounts were created to curate content, with some examples shown in Table 2.

Return on investment: does social media add to science communication?

Network science is an emerging and evolving specialty. Recent research suggests that sharing a traditional journal article on social media increases attention and downloads [66]. This can be facilitated in many ways, including discussing the study in a blog [66], posting short tweets, or sharing visual abstracts, images that summarize the main findings in a research paper [63,64,65, 67]. The latter has shown to increase attention to the study results in an appealing way with increased distribution and downloads as a result [62].

The importance of social media has thus become such that it is viewed as standard to disseminate articles via SoMe platforms [68]. SoMe is an increasing area of investigation across several surgical disciplines, with current studies pointing to differences in activity, with both positive and unchanged effects across various disciplines and outcomes [3, 6, 69,70,71,72,73,74]. Some journals, such as BJS, even summarize surgical Twitter activity from 1 month to another, to show highlights of debates and opinions [75,76,77,78].

Furthermore, social media communication of research results can reach broader audiences that traditionally have difficult access to scientific communication owing to journal paywalls and hermetic language. For instance, patient advocacy organizations and policy-makers can be kept appraised of new research findings in real time. This contributes to relaying and democratizing information for patients as well as impact on care processes and policies.

New metrics of impact: Altmetrics and more

For what it is worth and with all its flaws, scientific papers and researchers have traditionally been evaluated by the impact of their work based on where they publish (rank of journal and its impact factor), how many times their work is cited (for any given paper and time period), and their accumulating H-index (the sum of citations accrued over years of active research) [79, 80]. With the emergence of social media platforms, new bibliometric profiles measuring impact and exposure of scientific research online have been introduced as an Altmetrics (Fig. 6) to traditional bibliometric outcomes. Indeed, the influence of social media activity has become an interest for academics for several reasons [46], not only to gauge the actual tweets and retweets, but also whether this activity may turn into higher citation rates and wider impact of the research [47,48,49]. Currently, very few studies exist in general surgery, but one study found a positive correlation between Altmetric scores and citations [74]. Notably, Altmetric scores should not necessarily be used as a surrogate marker for evaluating research performance, impact, or exposure. It is possible, however, that as the use of social media for distributing and sharing scientific research continues to expand, that exposure on such platforms could impact future interest or studies.

An example of an Altmetric certificate. Some journals are now providing certificate to high Altmetric scoring papers, as shown in an example (a). The Altmetric score captures activity on social media platforms and news outlets, and gives an impression of immediate attention and global reach (b) but it is unclear to what degree this returns on citations or actual impact

One study found that Twitter activity was associated with higher research citation index among academic thoracic surgeons [50]. In a unique randomized study conducted among a network of cardiothoracic surgical journals [51] called the Thoracic Surgery Social Media Network [52, 53], the investigators compared tweeted articles to non-tweeted articles for their citation output at 1-year follow-up. When compared to control articles, tweeted articles achieved significantly higher Altmetric scores, with more citations at 1 year, highlighting the durable scholarly impact of social media activity [2]. Multivariable analysis showed that independent predictors of citations were randomization to tweeting, higher Altmetric score, open-access status, and exposure to a larger number of Twitter followers as quantified by impressions [51]. This is consistent with previous social media research [52].

Based on data from subspecialty surgery, as mentioned above for thoracic surgery [51] and also for vascular surgery [54], there seems to be positive correlation for some papers with higher citations after social media exposure. However, such correlation was not found in two studies on plastic and aesthetic surgery papers [48, 70] and only weak associations were found for Covid-19 papers [55]. Hence, it remains to be shown if these alternative metrics related to tweets, mentions in blogs, displays in news outlets, etc. will have any impact on the majority of research being published in surgical journals.

Some concerns of SoMe

Social media is an unedited, live, non-curated, short text–based forum where statements, claims, and voices may go unchecked yet widely distributed. There is a risk for false claims and so-called fake news [56] to appear—even in the scientific literature. Followers, readers, and participants need to keep a critical mind when reading and retweeting content—this has become even more prudent and scrutinized after the 2020 US presidential election, with impact of social media usage beyond political campaigns.

Creation of echo chambers is a real risk with SoMe, with a huge number of followers applauding a statement or claim, while shooting down any counterarguments (real or not). Sound debates really are fruitful, but “trolling” and “bullying” are threats to the sound debates in several instances.

There is a risk for influencers being heard and having a voice based on a strong presence and wide activity on social media, rather than being true experts or contributors to the scientific field or community per se. The discrepancy between the SoMe presence and the actual contribution to the field has been dubbed the “Kardashian index” by Hall [57]—simply “being famous for being famous,” without really having contributed. Identification of “influencers and Twitter stars” may be largely variable between specialties and countries [58, 59, 81, 82]. Few investigations exist into the matter, but some studies [82, 83] from the field of cardiology found that expert scientists have significantly more relevant audiences than so-called twitteratis (i.e., persons being influential through very high activity on Twitter) while the need for active participation and implication from the forefront of academia is still high. In addition, as long as true equity in academia remains a utopian dream, having a high Kardashian index may not be a bad thing, if it allows the playing field to be leveled; having fewer publications and citations does not make one’s opinions less valid, nor their contributions less valuable. As in any field of debate, it is crucial to separate actual information from mere noise.

Language and participation restrictions should also be noted. SoMe activity and use of various platforms are widely variable across the world. This can lead to the point of geographic exclusion as some regions are not participating or largely underrepresented in debates or discussions that become “truth” or “representative” of an opinion. Also, the use of professional and private use is very different between professionals [84], with some mixing both, others strictly professional and some merely for fun or social networking. However, the balance can be difficult and intriguing, particularly when considering conduct deemed unprofessional. Notably, a study published in J Vasc Surgery aimed to look into the matter of “unprofessional behavior” by fellow trainee colleagues [85], only to later be retracted from the same journal [86, 87]. The reason for the retraction was among others the inappropriate categorization of other persons’ behavior based on simple views on the said persons’ social media profile (e.g., a photo with a drink in hand; from a beach during vacation, or similar). This also created a response in the journal about who is to judge what is right and wrong [88], as well as a considerable “twitterstorm” (link here: https://twitter.com/JVascSurg/status/1286831352520888320). Indeed, the debate even led to the #MedBikini hashtag used by women doctors and allies globally that were offended by what male colleagues would deem inappropriate or unprofessional attire. Again, this has testified to the important role of SoMe to focus on diversity, gender equity, breaking down biases and stereotypes, and leveling out the playing field—with immediate action taken by journal editors [89].

Hence, several factors need to be kept in mind when interpreting the role and importance of debates and the content a hand. Suggestions to appropriate debate and collegial behavior for SoMe are available and published by societies or specialist journals [19, 90,91,92,93,94,95] and, importantly also, by most institutions these days. The most overarching point for surgeons and medical professional alike is nonetheless to maintain patient confidentiality and dignity at all times.

Patients may engage with surgeons on SoMe, which can be good thing; patients or their next of kin may learn about conditions in plain English (or the language in question at the platform), it may encourage public engagement, and doctors may get a perspective from the patient on priorities, wishes, thoughts, and needs. However, such contact can also potentially be concerning when crossing boundaries or conducted in an unprofessional manner. Some subspecialties may in particular have a fine line between providing information and bordering on actual advertisements for services [96,97,98,99].

Notably, technical issues should not be forgotten. A Twitter handle or social media account may be hacked or security breached. This should be considered both for the individual person but also if unusual or largely unexpected information is distributed from an account with unclear or largely deviating information.

Conclusions

Social media and their platforms have become yet another tool in the surgeon’s armamentarium for communication and dissemination of research, and for interacting with colleagues and the public. As such, SoMe platforms and several communities have become effective for sharing knowledge and opinions. Some caveats and pitfalls need to be considered and more research is needed into the real-world impact of these platforms. However, the sound use of this dissemination technology has allowed cutting-edge research to reach a wider audience with a lower threshold for discussing new information. Hence, we believe these channels will continue to shape surgeons’ way of obtaining new information, sharing new data, and engaging in scientific debates in the near future.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Ioannidis A, Blanco-Colino R, Chand M, Pellino G, Nepogodiev D, Wexner SD, Mayol J (2020) How to make an impact in surgical research: a consensus summary from the #SoMe4Surgery community. Updat Surg 72:1229–1235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00780-z

Han JJ (2020) To tweet or not to tweet: no longer the question. Ann Thorac Surg 111:300–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.070

Søreide K (2019) Numbers needed to tweet: social media and impact on surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 45(2):292–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.10.054

Soragni A, Maitra A (2019) Of scientists and tweets. Nat Rev Cancer 19(9):479–480. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-019-0170-4

Devitt S, Kenkel JM (2020) Social media: a necessary evil? Aesthet Surg J 40(6):700–702. https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjz361

Mayol J, Dziakova J (2017) Value of social media in advancing surgical research. Br J Surg 104(13):1753–1755. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10767

Maldonado AA, Lemelman BT, Le Hanneur M, Coelho R, Cristóbal L, Sader R et al (2020) Analysis of #PlasticSurgery in Europe: an opportunity for education and leadership. Plast Reconstr Surg 145(2):576–584. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000006427

Asyyed Z, McGuire C, Samargandi O, Al-Youha S, Williams JG (2019) The use of Twitter by plastic surgery journals. Plast Reconstr Surg 143(5):1092e–1098e. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000005535

Brady RRW, Chapman SJ, Atallah S, Chand M, Mayol J, Lacy AM, Wexner SD (2017) #colorectalsurgery. Br J Surg 104(11):1470–1476. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10615

BMJ T (2021) History of the BMJ. BMJ. https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/history-of-the-bmj. Accessed 7.2.2021.

Wikipedia (2021) Blog. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blog. Accessed 7.2.2021.

Wikipedia (2021) Podcast. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Podcast. Accessed 7.2.2021.

Campbell L, Evans Y, Pumper M, Moreno MA (2016) Social media use by physicians: a qualitative study of the new frontier of medicine. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 16:91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0327-y

Long LE, Leung C, Hong JS, Wright C, Young CJ (2019) Patterns of internet and social media use in colorectal surgery. BMC Surg 19(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0518-4

Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center. 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/. Accessed 7.2.2021.

Mackenzie G, Grossman R, Mayol J (2020) Beyond the hashtag: describing and understanding the full impact of the #BJSConnect tweet chat May 2019. BJS Open. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsopen/zraa019.

Zerrweck C, Arana S, Calleja C, Rodríguez N, Moreno E, Pantoja JP, Donatini G (2020) Social media, advertising, and internet use among general and bariatric surgeons. Surg Endosc 34(4):1634–1640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-06933-5

Cabrera LF, Ferrada P, Mayol J, Mendoza AC, Herrera G, Pedraza M, Sanchez S (2020) Impact of social media on the continuous education of the general surgeon, a new experience, @Cirbosque: a Latin American example. Surgery. 167(6):890–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2020.03.008

Bittner JG, Logghe HJ, Kane ED, Goldberg RF, Alseidi A, Aggarwal R et al (2019) A Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) statement on closed social media (Facebook®) groups for clinical education and consultation: issues of informed consent, patient privacy, and surgeon protection. Surg Endosc 33(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6569-2

Montemurro P, Cheema M, Tamburino S, Hedén P (2019) Online and social media footprint of all Swedish aesthetic plastic surgeons. Aesthet Plast Surg 43(5):1400–1405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-019-01392-8

Janik PE, Charytonowicz M, Szczyt M, Miszczyk J (2019) Internet and social media as a source of information about plastic surgery: comparison between public and private sector, A 2-center study. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 7(3):e2127. https://doi.org/10.1097/gox.0000000000002127

Ibrahim A, Abubakar LM, Maina DJ, Adebayo WO, Kabir AM, Asuku ME (2020) The millennial generation plastic surgery trainees in sub-Saharan Africa and social media: a review of the application of blogs, podcasts, and twitter as web-based learning tools. Ann Afr Med 19(2):75–79. https://doi.org/10.4103/aam.aam_25_17

Zhao JY, Romero Arenas MA (2019) The surgical blog: an important supplement to traditional scientific literature. Am J Surg 218(4):792–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.07.028

GastricCancerAssociation C (2021) NewsArchive. Gastriccancer.ca. http://gastriccancer.ca/newsletterarchive/.

Shippee ND, Domecq Garces JP, Prutsky Lopez GJ, Wang Z, Elraiyah TA, Nabhan M, Brito JP, Boehmer K, Hasan R, Firwana B, Erwin PJ, Montori VM, Murad MH (2015) Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect 18(5):1151–1166. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12090

Celentano V, Smart N, Cahill RA, McGrath JS, Gupta S, Griffith JP et al (2019) Use of laparoscopic videos amongst surgical trainees in the United Kingdom. Surgeon 17(6):334–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2018.10.004

Jyot A, Baloul MS, Finnesgard EJ, Allen SJ, Naik ND, Gomez Ibarra MA, Abbott EF, Gas B, Cardenas-Lara FJ, Zeb MH, Cadeliña R, Farley DR (2018) Surgery website as a 24/7 adjunct to a surgical curriculum. J Surg Educ 75(3):811–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.09.019

Clarke Hillyer G, Basch CH, Guerro S, Sackstein P, Basch CE (2019) YouTube videos as a source of information about mastectomy. Breast J 25(2):349–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.13222

Ferhatoglu MF, Kartal A, Filiz A, Kebudi A (2019) Comparison of new era’s education platforms, YouTube® and WebSurg®, in sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg 29(11):3472–3477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04008-x

Almarghoub MA, Alghareeb MA, Alhammad AK, Alotaibi HF, Kattan AE (2020) Plastic surgery on YouTube. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 8(1):e2586. https://doi.org/10.1097/gox.0000000000002586

Sturiale A, Dowais R, Porzio FC, Brusciano L, Gallo G, Morganti R, Naldini G (2020) YouTube as a source of patients and specialists’ information on hemorrhoids and hemorrhoid surgery. Rev Recent Clin Trials 15:219–226. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574887115666200525001619

Ferhatoglu MF, Kartal A, Ekici U, Gurkan A (2019) Evaluation of the reliability, utility, and quality of the information in sleeve gastrectomy videos shared on open access video sharing platform YouTube. Obes Surg 29(5):1477–1484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03738-2

Keskinkılıç Yağız B, Yalaza M, Sapmaz A (2020) Is Youtube a potential training source for total extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair? Surg Endosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07596-3

de Angelis N, Gavriilidis P, Martínez-Pérez A, Genova P, Notarnicola M, Reitano E et al (2019) Educational value of surgical videos on YouTube: quality assessment of laparoscopic appendectomy videos by senior surgeons vs. novice trainees. World J Emerg Surg 14:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-019-0241-6

Frongia G, Mehrabi A, Fonouni H, Rennert H, Golriz M, Günther P (2016) YouTube as a potential training resource for laparoscopic fundoplication. J Surg Educ. 73(6):1066–1071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.04.025

Dixon M, Palter V, Brar S, Coburn N (2021) Evaluating quality and completeness of gastrectomy for gastric cancer: review of surgical videos from the public domain. Transl Gastro Hepatol.

Laurentino Lima D, RNCL L, Benevenuto D, Soares Raymundo T, Shadduck PP, Melo Bianchi J et al (2020) Survey of social media use for surgical education during Covid-19. JSLS 24(4):e2020.00072. https://doi.org/10.4293/jsls.2020.00072

Chang H-C (2010) A new perspective on Twitter hashtag use: diffusion of innovation theory. Proc Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 47(1):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.14504701295

Grossman RC, Mackenzie DG, Keller DS, Dames N, Grewal P, Maldonado AA, Ioannidis A, AlHasan A, Søreide K, Teoh JYC, Wexner SD, Mayol J (2020) #SoMe4Surgery: from inception to impact. BMJ Innovations 6(2):72–82. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2019-000356

Morello L (2015) Science and sexism: in the eye of the twitterstorm. Nature. 527(7577):148–151. https://doi.org/10.1038/527148a

Ansari H, Pitt SC (2020) #ILookLikeASurgeon: or do I? The local and global impact of a hashtag. Am J Surg. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.10.020.

Loeb S, Byrne NK, Thakker S, Walter D, Katz MS (2020) #ILookLikeAUrologist: using Twitter to discuss diversity and inclusion in urology. Eur Urol Focus. 10.1016/j.euf.2020.03.005.

Do A-M (2014) The real reason why Facebook dominates Vietnam but Twitter could never make it. TechInAsia, TechInAsia. https://www.techinasia.com/vietnam-loves-facebook-not-twitter. Accessed 7.2.2021.

Coca N (2018) Why Japan loves Twitter more than Facebook. OZY, OZY. https://www.ozy.com/around-the-world/why-japan-loves-twitter-more-than-facebook/86545/. Accessed 7.2.2021.

Kalev L, Shaowen W, Guofeng C, Anand P, Eric S (2013) Mapping the global Twitter heartbeat: the geography of Twitter. First Monday 18(5). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v18i5.4366

Maggio LA, Meyer HS, Artino AR Jr (2017) Beyond citation rates: a real-time impact analysis of health professions education research using altmetrics. Acad Med 92(10):1449–1455. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001897

Grant MC, Scott-Bridge KR, Wade RG (2020) The role of social media in disseminating plastic surgery research: the relationship between citations, altmetrics and article characteristics. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2020.10.103

Boyd CJ, Ananthasekar S, Kurapati S, King TW (2020) Examining the correlation between altmetric score and citations in the plastic surgery literature. Plast Reconstr Surg 146(6):808e–815e. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000007378

Richardson MA, Bernstein DN, Mesfin A (2020) Manuscript characteristics associated with the altmetrics score and social media presence: an analysis of seven spine journals. Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2020.11.001

Coret M, Rok M, Newman J, Deonarain D, Agzarian J, Finley C, Shargall Y, Malik PRA, Patel Y, Hanna WC (2019) Twitter activity is associated with a higher research citation index for academic thoracic surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg 110:660–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.09.075

Luc JGY, Archer MA, Arora RC, Bender EM, Blitz A, Cooke DT, Hlci TN, Kidane B, Ouzounian M, Varghese TK Jr, Antonoff MB (2020) Does tweeting improve citations? One-year results from the TSSMN prospective randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg 111:296–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.065

Luc JGY, Archer MA, Arora RC, Bender EM, Blitz A, Cooke DT, Hlci TN, Kidane B, Ouzounian M, Varghese TK Jr, Antonoff MB (2020) Social media improves cardiothoracic surgery literature dissemination: results of a randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg 109(2):589–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.06.062

Ni hIci T, Archer M, Harrington C, JGY L, Antonoff MB (2020) Trainee thoracic surgery social media network: early experience with TweetChat-based journal clubs. Ann Thorac Surg 109(1):285–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.05.083

Chau M, Ramedani S, King T, Aziz F (2020) Presence of social media mentions for vascular surgery publications is associated with an increased number of literature citations. J Vasc Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.09.029.

Tornberg HN, Moezinia C, Wei C, Bernstein SA, Wei C, Al-Beyati R et al (2021) Assessing the dissemination of COVID-19 articles across social media with Altmetric and PlumX metrics: correlational study. J Med Internet Res 23(1):e21408. https://doi.org/10.2196/21408

Gilligan JT, Gologorsky Y (2019) #Fake News: scientific research in the age of misinformation. World Neurosurg 131:284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.08.083

Hall N (2014) The Kardashian index: a measure of discrepant social media profile for scientists. Genome Biol 15(7):424. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0424-0

Elson NC, Le DT, Johnson MD, Reyna C, Shaughnessy EA, Goodman MD et al. (2020) Characteristics of general surgery social media influencers on Twitter. Am Surg :3134820951427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003134820951427.

Varady NH, Chandawarkar AA, Kernkamp WA, Gans I (2019) Who should you be following? The top 100 social media influencers in orthopaedic surgery. World J Orthop 10(9):327–338. https://doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v10.i9.327

Breu AC (2020) From tweetstorm to tweetorials: threaded tweets as a tool for medical education and knowledge dissemination. Semin Nephrol 40(3):273–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2020.04.005

Heßler N, Rottmann M, Ziegler A (2020) Empirical analysis of the text structure of original research articles in medical journals. PLoS One 15(10):e0240288. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240288

Ibrahim AM, Lillemoe KD, Klingensmith ME, Dimick JB (2017) Visual abstracts to disseminate research on social media: a prospective, case-control crossover study. Ann Surg 266(6):e46–ee8. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002277

Chapman SJ, Grossman RC, FitzPatrick MEB, Brady RRW (2019) Randomized controlled trial of plain English and visual abstracts for disseminating surgical research via social media. Br J Surg 106:1611–1616. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11307

Ramos E, Concepcion BP (2020) Visual abstracts: redesigning the landscape of research dissemination. Semin Nephrol 40(3):291–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2020.04.008

Ibrahim AM (2018) Seeing is believing: using visual abstracts to disseminate scientific research. Am J Gastroenterol 113(4):459–461. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2017.268

Buckarma EH, Thiels CA, Gas BL, Cabrera D, Bingener-Casey J, Farley DR (2017) Influence of social media on the dissemination of a traditional surgical research article. J Surg Educ. 74(1):79–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.06.019

Nikolian VC, Ibrahim AM (2017) What does the future hold for scientific journals? Visual abstracts and other tools for communicating research. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 30(4):252–258. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1604253

Johannsson H, Selak T (2020) Dissemination of medical publications on social media—is it the new standard? Anaesthesia. 75(2):155–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14780

Sathianathen NJ, Lane R 3rd, Condon B, Murphy DG, Lawrentschuk N, Weight CJ, Lamb AD (2020) Early online attention can predict citation counts for urological publications: the #UroSoMe_Score. Eur Urol Focus 6(3):458–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2019.10.015

Asaad M, Howell SM, Rajesh A, Meaike J, Tran NV (2020) Altmetrics in plastic surgery journals: does it correlate with citation count? Aesthet Surg J 40:NP628–NP635. https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjaa158

Kunze KN, Polce EM, Vadhera A, Williams BT, Nwachukwu BU, Nho SJ, Chahla J (2020) What is the predictive ability and academic impact of the altmetrics score and social media attention? Am J Sports Med 48(5):1056–1062. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546520903703

Smith ZL, Chiang AL, Bowman D, Wallace MB (2019) Longitudinal relationship between social media activity and article citations in the journal Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 90(1):77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2019.03.028

Tonia T, Van Oyen H, Berger A, Schindler C, Künzli N (2020) If I tweet will you cite later? Follow-up on the effect of social media exposure on article downloads and citations. Int J Public Health 65(9):1797–1802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01519-8

Mullins CH, Boyd CJ, Corey BL (2020) Examining the correlation between altmetric score and citations in the general surgery literature. J Surg Res 248:159–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2019.11.008

Grossman RC (2019) This month on Twitter. Br J Surg 106(7):814. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11255

Grossman R (2019) Tweets of the month—January. Br J Surg 106(3):297. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11130

Grossman RC (2020) This month on Twitter. Br J Surg 107(13):1855. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.12071

Grossman RC (2020) Tweets of the month. Br J Surg 107(1):155. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11492

Aroeira RI (2020) M ARBC. Can citation metrics predict the true impact of scientific papers? FEBS J 287(12):2440–2448. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15255

Chapman CA, Bicca-Marques JC, Calvignac-Spencer S, Fan P, Fashing PJ, Gogarten J, Guo S, Hemingway CA, Leendertz F, Li B, Matsuda I, Hou R, Serio-Silva JC, Chr. Stenseth N (2019) Games academics play and their consequences: how authorship, h-index and journal impact factors are shaping the future of academia. Proc Biol Sci 286(1916):20192047. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.2047

You J (2014) Scientific community. Who are the science stars of Twitter? Science. 345(6203):1440–1441. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.345.6203.1440

Khan MS, Shahadat A, Khan SU, Ahmed S, Doukky R, Michos ED, Kalra A (2020) The Kardashian index of cardiologists: celebrities or experts? JACC Case Rep 2(2):330–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccas.2019.11.068

Pawar S, Siddiqui G, Desai NR, Ahmad T (2018) The Twittersphere Needs Academic Cardiologists!: #heartdisease #No1Killer #beyondjournals. JACC Heart Fail 6(2):172–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2017.10.008

Langenfeld SJ, Vargo DJ, Schenarts PJ (2016) Balancing privacy and professionalism: a survey of general surgery program directors on social media and surgical education. J Surg Educ 73(6):e28–e32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.07.010

Hardouin S, Cheng TW, Mitchell EL, Raulli SJ, Jones DW, Siracuse JJ, Farber A (2019) Prevalence of unprofessional social media content among young vascular surgeons. J Vasc Surg 72:667–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.10.069

(2020) Retraction notice. J Vasc Surg 72(4):1514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.08.018.

Hardouin S, Cheng TW, Mitchell EL, Raulli SJ, Jones DW, Siracuse JJ, Farber A (2020) RETRACTED: prevalence of unprofessional social media content among young vascular surgeons. J Vasc Surg 72(2):667–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.10.069

Stamp N, Mitchell R, Fleming S (2020) Social media and professionalism among surgeons: who decides what’s right and what’s wrong? J Vasc Surg 72(5):1824–1826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.07.076

Sosa JA (2020) Editorial: doubling down on diversity in the wake of the #MedBikini controversy. World J Surg 44(11):3587–3588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05751-4

Cho MJ, Furnas HJ, Rohrich RJ (2019) A primer on social media use by young plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg 143(5):1533–1539. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000005533

Kung JW, Wigmore SJ (2020) How surgeons should behave on social media. Surgery (Oxf) 38(10):623–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpsur.2020.07.014

Bernardi K, Shah P, Askenasy EP, Balentine C, Crabbe MM, Cerame MA et al (2020) Is the American College of Surgeons Online Communities a safe and useful venue to ask for surgical advice? Surg Endosc 34(11):5041–5045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-07299-4

Bailey A (2019) Social media: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Plast Surg Nurs 39(3):66. https://doi.org/10.1097/psn.0000000000000271

Chen AD, Furnas HJ, Lin SJ (2020) Tips and pearls on social media for the plastic surgeon. Plast Reconstr Surg 145(5):988e–996e. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000006778

McNeely MM, Shuman AG, Vercler CJ (2020) Ethical use of public networks and social media in surgical innovation. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2019.0758

Atiyeh BS, Chahine F, Abou Ghanem O (2020) Social media and plastic surgery practice building: a thin line between efficient marketing, professionalism, and ethics. Aesthetic Plast Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-020-01961-2.

Varghese TK Jr, Entwistle JW 3rd, Mayer JE, Moffatt-Bruce SD, Sade RM (2019) Ethical standards for cardiothoracic surgeons’ participation in social media. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 158(4):1139–1143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.03.029

Hetzler PT, Makar KG, Baker SB, Fan KL, Vercler CJ (2020) Time for a consensus? Considerations of ethical social media use by pediatric plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg 146(6):841e–842e. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000007389

Schoenbrunner A, Gosman A, Bajaj AK (2019) Framework for the creation of ethical and professional social media content. Plast Reconstr Surg 144(1):118e–125e. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000005782

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bergen (incl Haukeland University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grossman, R., Sgarbura, O., Hallet, J. et al. Social media in surgery: evolving role in research communication and beyond. Langenbecks Arch Surg 406, 505–520 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02135-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02135-7